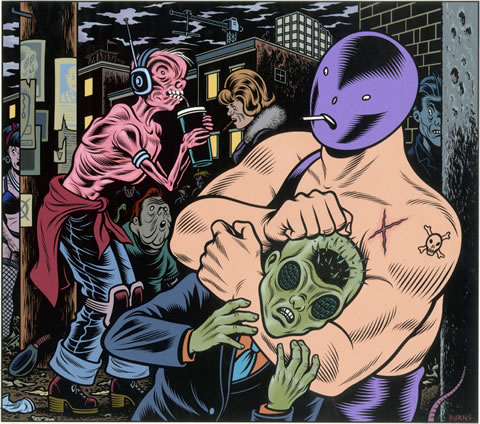

Charles Burns:

Almost Inhuman

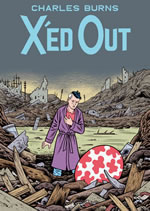

Charles Burns is today’s undisputed master of unsettling creepiness and not only in such American comics as Big Baby, Dog Boy, El Borbah, Black Hole and his latest, X’ed Out, but also in photography, animation, and set and costume design.

Through much of his practice runs an obsession about the transformations triggered by adolescent sexual awakenings and more broadly about the fears of losing control over one’s body and mind through accident, disease, surgery or worse. Perhaps partly as a reaction to this fear Burns controls his inky lines with extraordinary precision, honed and hard-edged, resonant of the industrialised yet often eccentric genre comic books he grew up devouring. Burns makes the shadows and textures on skin, hair, clothes and vegetation shimmer and pulse with painstaking brushstrokes as toothy as a chainsaw. Robert Crumb no less hailed Burns’ artwork as “almost inhuman”. Though tinted at times in flat colours, his is a black and white world, much more black than white, saturated with the darkness of the soul.

Catching him amidst preparations for his first major retrospective organised by BeeldBeeld at the Museum M in Leuven, Belgium, was the perfect time to get some perspectives on his oeuvre.

Charles Burns, photo by Michel Lunardelli

Paul Gravett:

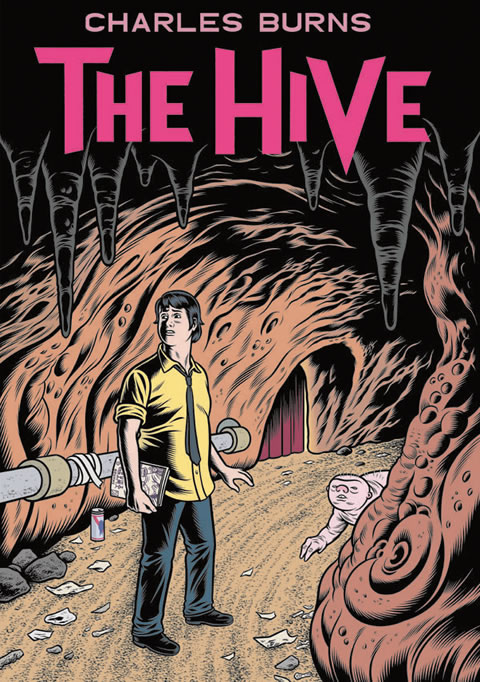

You’re working on The Hive, the second part of your trilogy inspired by Tintin. What fascinated you about Hergé‘s albums?

Charles Burns:

As a child, I spent countless hours staring at their back covers and fantasising about the characters and imagery from the books I didn’t own - there were only six books available at that time in the U.S.. I would have done anything to get my hands on a copy of The Black Island; that castle looming off in the distance was incredibly mysterious and such a potent image. When I finally read the story in my late teens, it couldn’t possibly live up to my expectations even though it’s still a great book. Perhaps I’m trying to create the dark, mysterious world I saw in that tiny drawing in my own work - at least I’m trying to create stories that have the same strong, rich atmosphere. Mine are just a bit darker.

Preliminary cover design for The Hive

What the significance of the title X’ed Out?

It means “crossing something off” of a list, as in the middle of the story where Doug has made a handmade calendar for his attempt at a reduction cure of the opiates he’s become addicted to. On the calendar, he crosses out the days (with an ‘X’) much the way someone in prison would do if they were marking the time of their incarceration. The title also works on a lot of other levels - taking on a punk persona could be a way of crossing yourself out of mainstream American culture. And one of my favourite bands from that era was called ‘X’... and so on.

William Burroughs is another noticeable influence on X’ed Out, noticeably where you have your protagonist Doug do a spoken word performance.

Yes, I was reading a lot of Burroughs at the time when this story takes place in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so it made sense for me to have the protagonist try his hand at Burroughs-influenced cut-up writing. It’s a fun, young, naive thing I actually did myself when I was Doug’s age. There was a dark spirit in Burroughs’ work that repelled me and yet seduced me at the same time. Keep in mind I was reading him in the 1970s and even though the wave of hippy optimism was faltering and ready to crash, American youth culture was still heavily under the influence of utopian, back-to-nature dreams expressed by bands like Crosby, Stills and Nash and James Taylor. It was such a relief for me to read something that mirrored some of the disgust and horror I felt walking around in my body and to acknowledge that everything wasn’t about “peace and love” (unfortunately). Burroughs also reflected some of the sensibilities expressed in the punk music I was starting to listen to. His work was urban and direct and took an unflinching look at the world around him and he didn’t take himself too seriously.

How much have you used Burroughs literary techniques such as his cut-ups in X’ed Out?

The only place I actually use randomly cut-in words would be when Doug is getting up in front of an audience and doing his “performance” - there I use my words from other parts of the story cut in with a few lines from Naked Lunch and Soft Machine. Some of the ways in which I’m writing the story at times mimics a seemingly random juxtaposition of images (something Burroughs did very well) but there’s nothing random about it as far as my work is concerned. Everything is there for a very precise reason.

How important has photography been in your artistic development?

I’ve always been interested in photography. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, right around the time of the events in X’ed Out, I took a lot of SX-70 Polaroids with titles like “The Heart of Flesh” and “Razor blade cut in the arm”. They’re typical of the kind of imagery I was photographing in that era of my life, which I’m reflecting on in this current story. After many years I returned to photography in my book One Eye, while I was finishing Black Hole. With the availability of high quality digital cameras I started keeping a “photo diary”, forcing myself to come up with two paired photos every day. Sometimes in One Eye I used old photos like “the heart of flesh” and “razor blade cut in the arm” and I came back to these images in X’ed Out. I guess there’s always a “crosspollination” in all of my work. I don’t always have a rational explanation for including these unfiltered images from my subconscious, other than the fact that they feel authentic and carry some power for me.

You also made use of photography to create the story The Cat Woman Returns in 1979. You’ve commented in Todd Hignite’s In the Studio that creating this photo comic forced you “to organise and structure the narrative in a way you’d never really done before”. How did this experiment change your practice?

The comics I had created prior to The Cat Woman Returns had always had a primary focus on the artwork as opposed to the writing. I had managed to create plenty of short, self-contained pieces but I’d never really managed to sustain a longer narrative. Keep in mind that the story for my photo comic was really dumb, but because of the fact that I needed to get out and photograph the story in the real world, I had to plan and organize the story before hand rather than sit down at a drawing table and let the story unfold on its own. As long as I had a fairly clear idea what the subject was, I could set up my photo shoots and take a large number of photos and then size and edit the images into pages later on. The process allowed me to step away from the actual drawing of my comics and think more in terms of the pacing, page design, narrative and dialogue. I’ve never tried creating photo comics again because they always look a little lame, but I was actually trying to emulate that cheesy quality, the overly dramatic imagery found in Italian and Mexican photo romance comics.

Black Hole draws on your own anxieties as an adolescent. How much of yourself are you incorporating into this new trilogy?

There’s a part of me in all of my characters but in my more recent work, I’ve made an effort to put more of myself into the story to make them more “character driven”. With X’ed Out, I’m getting closer to depicting how my brain actually works. Doug slowly reveals his story in a very elliptical, elusive way, almost as if he’s “in denial” but still trying to examine and analyse the predicament he finds himself in. The fragmented storytelling and the free association with dream/fantasy imagery reflect his thought process and ultimately reflects mine as well. So Doug isn’t really a fictional version of me but his experiences, both internal and external are a reflection of my experiences. Though I was never as good-looking as most of the characters I draw in Black Hole and X’ed Out. And I never got to meet a girl with a tail. Not yet anyway.

Posted: November 20, 2011This article first appeared in Art Review magazine in November 2011.