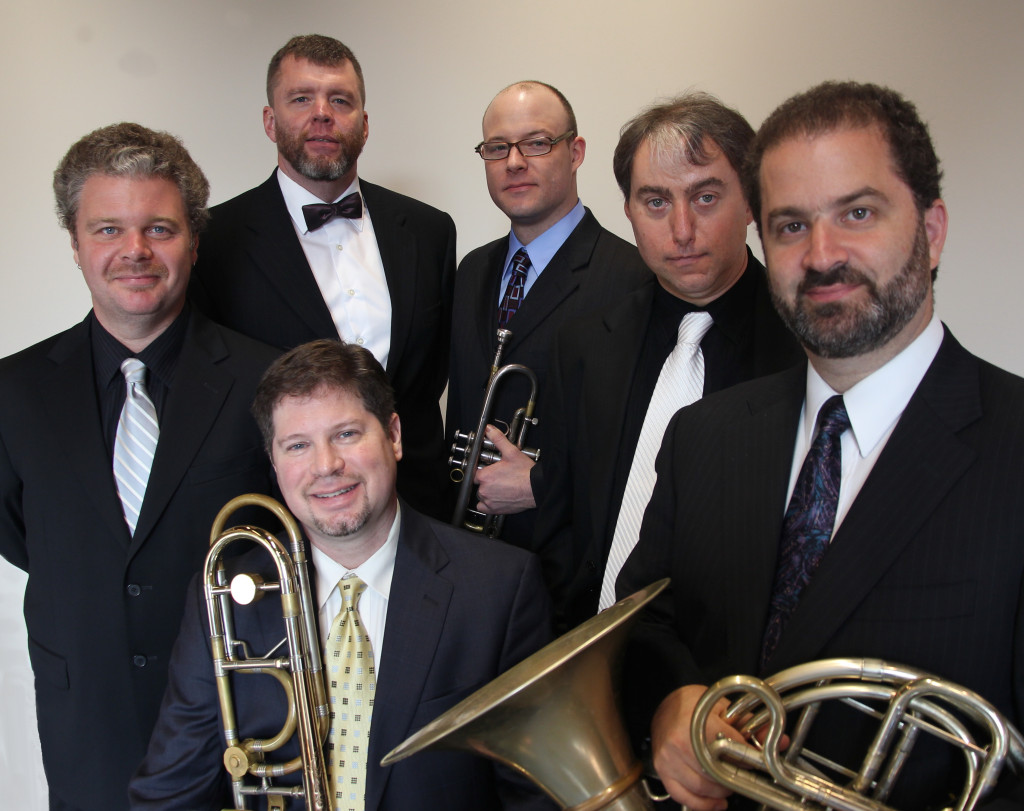

The American Brass Quintet is comprised of:

trumpets (Kevin Cobb & Louis Hanzlik),

horn (Eric Reed), and

tenor and bass trombones (Michael Powell & John D. Rojak).

The American Brass Quintet is distinguished in so many ways. As educators, their residencies at Aspen and Juilliard alone have shaped generations of the most promising brass musicians, not to mention their innovative residencies around the globe. As preservationists of a traditional chamber music approach to brass (which more closely parallels that of a string quartet), they are unmatched. From the ABQ dedication to the more evenly matched timbres of two trumpets and two trombones as the core of a brass quintet, to their persistence in bringing new music for brass to every concert, they are the champions of art music for brass. With a bass trombonist as the bottom voice, it was perhaps natural to take advantage of brass literature from earlier historical style periods, to have done so with such detailed vigor is unprecedented. With over 150 new pieces commissioned and premiered for brass, 50 albums, countless tours, and an impressive array of current and former members, the American Brass Quintet has literally shaped the course of chamber music in America for more than half a century.

“FIVE!” tm is delighted to host the innovative American Brass Quintet as featured guests for our chamber music interview series. Our respondents are:

Eric Reed-ER, French horn (formerly of the Canadian Brass)

Michael Powell-MP, tenor trombone

John Rojak-JR, bass trombone

How would you describe the distinct musical values passed down from the ABQ founding members to the current performers?

When ABQ was founded, the members at that time made it their mission to champion music written for brass instruments and to avoid transcriptions of popular classical music, jazz, and music that had been written for other ensembles. Our current group continues that tradition which has resulted in over 150 pieces from composers of our time, as well as dozens of editions of early music adapted from music written for the predecessors of modern brass instruments. We have always known that a concert of original brass music can be entertaining and leave an audience richer for that experience. JR

How do you view the development of the Brass Quintet in the United States, and the role of the ABQ in that development?

Brass quintets started developing in the mid-20th century and all brass players owe thanks to Robert King, who published a wealth of arrangements and original pieces starting in the late 1930’s. The New York Brass Quintet made an incredible impact with their domestic touring in the 1950’s and ‘60’s, bringing serious brass chamber music to many audiences. (By the way, before Harvey Phillips played tuba with NYBQ, the bottom voice was Julius Mencken on bass trombone!) ABQ came along in 1960 and continued what NYBQ had begun, commissioning new works, touring internationally and showing brass as a viable option on chamber music series. The Eastman Brass Quintet, Annapolis Brass and other groups formed and brass music began to develop a repertoire. When the Canadian Brass changed the nature of brass music in the 1970’s, some of those ensembles had a harder time programming serious repertoire. Many groups emulated the CB model, and ABQ became more unique in the field. Currently, it seems that audiences can accept the ABQ and the CB models and young quintets have been formed that play serious rep, light rep, and a mix of styles.

ABQ’s role in brass quintet development has been long term, and we think deep rooted. ABQ has been highly influential, commissioning leading composers of our time and recording dozens of those pieces, giving audiences and performers access to brass music of Ewazen, Sampson, Druckman, and many others. We have performed on 5 continents, 50 states, and reached many thousands of people. With residencies at the Aspen Music Festival since 1970 and Juilliard since 1987, we have coached many brass players and shared our values about chamber music. Many of those students have become performers and teachers, passing on ABQ traditions to the next generations. JR

How would you describe the access to composers, musicians and cultural influences that have arisen due to your residence in New York City?

New York City is truly a melting pot of all sorts of influences. We are lucky to be rubbing shoulders with both preeminent and aspiring artists on a daily basis, and that continues to inspire us. I absolutely love the variety of experiences the city offers to artists. Just to think that for every event occurring in NYC there are at least another hundred occurring at the very same time-all with different musicians, music and composers behind the music, is truly mind-boggling. If we could only be in 100 places at once! The knowledge that other inspired creators of art are right around the corner, perhaps even on the cusp of writing the greatest brass quintet ever written, drives us to keep on our mission to find them-and to get them to write it. We are in a wonderful place to be able to do that. -ER

Adapting to different styles is arguably the most challenging for a brass chamber music due to the greater span of historical music, and the intensity with which the brass timbres were explored during the 20th century-particularly in jazz. As one of the few groups who excel at each style, how does ABQ maintain artistic integrity at such a daunting challenge?

Our artistic integrity is due to performing music written for brass quintet or the predecessors of our instruments. In early music, that means cornetti and sackbuts, or 5 part instrumental music, and in some cases, vocal music from the Renaissance. We consider our early music performances to be historically informed. We have spent time studying treatises and listening to fine examples of performances by musicians who have dedicated their careers to those styles. Contemporary music is actually easier in many ways. Composers tend to mark the score precisely how they want it heard, and better still, we can talk to them! We always spend time with composers who write for us and make sure we are representing the music as intended. JR

What is it like to tour with the ABQ? On the bus? After the concert? What have been some of your most memorable audiences?

The current members of ABQ are having a blast on tour! Our first major tour with Louis and Eric was 3 weeks in Australia. We spent a lot of time together, eating probably 80% of our meals as a group. We had some wonderful nights after concerts, but we’re a fairly conservative bunch—no wild parties or morning hangovers. We talk! We’ve had many memorable audiences and concerts, but perhaps the most moving in recent memory was in Prague shortly after 9/11. We played “Ah! dolente partita†by Monteverdi, a madrigal with text that refers to painful separation, in St. Bartholomew’s Church. The ambience of the church, the ring off of beautiful harmony, and the hushed, then warm, reception of the full house was stunning. The empathy towards us as Americans in the time following our country’s tragedy was incredibly touching. JR

The ability of brass to radically alter their timbre seems vastly superior to other acoustic instruments, and yet sometimes rarely prized. Can you address the pros and cons of mutes, and whether you think that they are under-utilized?

I’d say mutes are not under-utilized by any means in the ABQ. It’s difficult to navigate the stage setup without kicking one, and some of the trombone mutes I see on stage look like alien spacecrafts!

Indeed, there is always room for more color, it’s just a matter of how the mutes are utilized, by the composer and by the player. The trumpet players in ABQ are continuously getting new versions of similar mutes because they are shaped differently or made of a heavier material or offer different tuning options. It’s a wild world of mutes out there, and the ABQ utilizes most if not all of them. I agree, it’s an amazing thing about brass writing that mutes can so vastly alter the sound and color. The only down side that I can see is carrying the things in our luggage! -ER

Indeed, there is always room for more color, it’s just a matter of how the mutes are utilized, by the composer and by the player. The trumpet players in ABQ are continuously getting new versions of similar mutes because they are shaped differently or made of a heavier material or offer different tuning options. It’s a wild world of mutes out there, and the ABQ utilizes most if not all of them. I agree, it’s an amazing thing about brass writing that mutes can so vastly alter the sound and color. The only down side that I can see is carrying the things in our luggage! -ER

What is a quintet warm-up like with the ABQ?

I have been in the ABQ for over 30 years, and there has never been a coordinated quintet warm-up. It sounds like a fine idea for a younger ensemble, however. Even when warming up independently in the same room, acceptable manners absolutely apply: Always be personally and musically polite regarding sound level, intonation, and your own passage-work connected with your warm-up. -MP

With the ABQ it is clearly all about the music, and yet the prominence of the bass trombone (certainly not to the exclusion of the tuba), often gives your ensemble a characteristic sound. How would you describe the ABQ relationship with the bass trombone, and what do you make of the trend for smaller tubas in other brass quintets?

The use of tuba in a brass quintet adds a nice roundness of sound, coupling with the conical French horn in a pleasing way. That said, it’s a bit like using a double bass in a string quartet instead of a cello; certain voicings and instrument ranges leave something to be desired in the middle of the spectrum. In the ABQ, the matching qualities of the two pairs of trumpets and trombones create a nice balance of sound timbre, which I think outweigh the sometimes deeper, rounder quality of a quintet with tuba. As for the popular use of smaller tubas in brass quintet, the often unfortunate trade-off for easier transport is a lack of full, round tuba sound mentioned above, and a wonky low-register, which begs the question, why use tuba after all? Nothing against tuba in brass quintet, it just presents more challenges, including overhead bins. We’re happy with the bass trombone for so many reasons. -ER

Describe the ABQ commitment to new music and composers. How do you find it best to bring challenging pieces before the public?

From the beginning, one leg of the ABQ’s mission is to foster new works for the genre. Having a new work embedded in a mixed program is our method of introducing our audiences to music of our time. In general, the newest work is performed at the end of the first half of the recital, after playing older, stylistically familiar works which more easily connect with many concertgoers. On tour, we always speak from the stage between works, which is undoubtedly helpful in introducing the audience to us and the music-whether old or new. -MP

Which are the chamber music groups that inspire you?

Which are the chamber music groups that inspire you?

We often say that a goal of the ABQ is to be on the same chamber music series as string quartets and piano trios, and I’d say we are achieving that goal in virtually every venue. In order to be fully aware of what those chamber groups bring to a series, it’s important for us to see them perform. In the last month, we’ve been fortunate to be presented alongside the American and Borromeo String Quartets at the Aspen and Cape Cod festivals, respectively. Hearing and seeing those fantastic quartets perform was truly inspiring. -ER

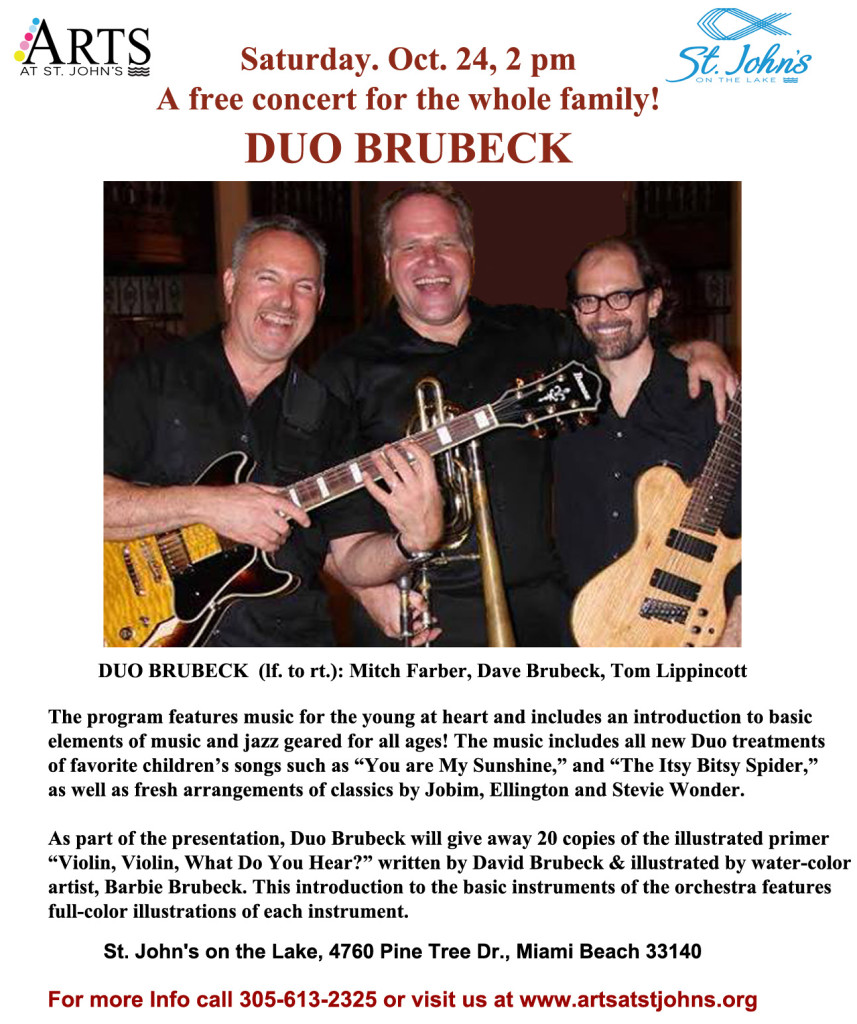

c. 2015 David William Brubeck All Rights Reserved www.davidbrubeck.com

Photos courtesy of Juilliard and the ABQ

Interested in more “FIVE!” tm interviews?

Canadian Brass 2014, Windsync 2014, Boston Brass 2015, Mnozil Brass 2015, Spanish Brass 2014, Dallas Brass 2014, Seraph 2014, Atlantic Brass Quintet 2015, Mirari Brass 2015, Axiom Brass 2015, Scott Hartmann of the Empire Brass 2015, Jeffrey Curnow of the Empire Brass 2015, Ron Barron and Ken Amis of the Empire Brass, Meridian Arts Ensemble 2015, Berlin Philharmonic Woodwind Quintet 2015, American Brass Quintet 2015