Looking at Bach’s Badinerie reveals a great deal about his immense craftsmanship as a composer. In this article, therefore, I want to look at and learn from this craftsmanship. Therefore, to start, we will discuss the texture and instrumentation of Badinerie. We will then look at larger and smaller scale issues of tonality and harmony. Finally, we will look at Bach’s use of melody and motif. Use the contents below to navigate to what you would like to know.

Texture, Counterpoint and Instrumentation

Bach’s Badinerie is primarily for an orchestra comprised of flute and string orchestra, with the string orchestra including, what is known as, a basso part. The basso could be a bass instrument within that string orchestra, or it could be a keyboard or plucked string instrument, typical of the Baroque period, such as the harpsichord or theorbo.

The delineation of a basso part, with figured bass instructions that a harpsichord or theorbo player could realise, is reflective of practice during this time. Furthermore, just as practice does, this shapes the composition, particularly in its texture. For instance, while this composition has a melody line, usually taken up by the flute, the bass is in counterpoint throughout, which gives the outer voices a great deal of independence and importance. The inner string lines primarily realise the figured bass harmony that the basso part has printed underneath it. (At least in certain editions. In my extracts, I have left out the figured bass. This was primarily to save time in making them.)

If we extract the outer voices, the flute and basso, as I do here in this vide, we can hear how much of the compositions energy and integrity remains. We can also hear the contrapuntal relationship, between flute and basso, in isolation.

Flexible Instrumentation

I am not a Baroque or historical performance specialist. Therefore, I can only comment on this from what limited knowledge I have on the subject and as a composer. However, it would seem the practice of using basso and figured bass facilitates flexibility in instrumentation. In other words, the hierarchy of melody, basso and then string parts means it could be successfully performed in a range of formats, with little to no adaptation. For example, a continuo player might be able to play the piece alone, without any adaptation to the score. Or in combination with a soloist. The same could not be said for many other Western styles of music, where straight adaptation would be difficult or impossible.

Here is an arrangement, albeit deliberately made in this instance, for solo piano. However, reflecting on the earlier example I provide of the outer voices in isolation, much of the original character remains.

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

The Lark Ascending (Music Composition Analysis) – Ralph Vaughan Williams (Article 1 – Lessons in Harmony)

How to repeat melodies without them getting boring… [Video]

5 ways of Understanding woodwinds

Arabesque No. 1 – Claude Debussy (Music Composition Analysis)

Spiegel im Spiegel – Arvo Pärt

Salut D’amour – Edward Elgar (Music Composition Technique Analysis)

Tonality and Binary Form

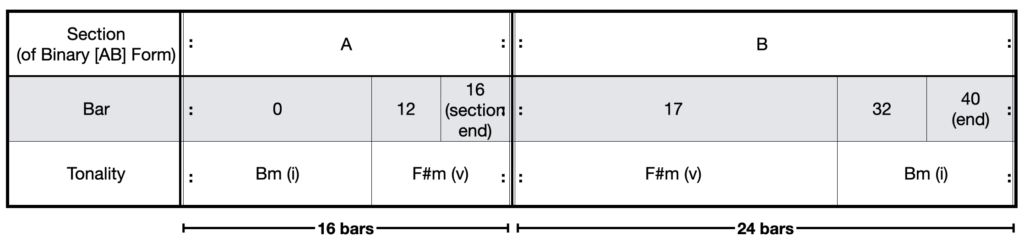

Looking closer at the music, the tonal procedures that Bach uses are, surprisingly, straightforward. They also support the Binary form structure of the piece. For example, the first section of the work starts in B-minor, ending in the dominant-minor of F-sharp. With regards to composition technique and style, this modulation is an invaluable device to Bach. It not only creates a feeling of change but it also remains close enough to B-minor so that he can simply have the music repeat. Doing this gives him 32-bars for the price of 16, kerching!

The second section, of the binary form, reverses the process and Bach is able to get an even better deal of 48-bars for the price of 24. Continuing the F-sharp minor tonality that ends the first part, Bach closes the piece in B-minor. Just like before, this means a simple repeat can occur without a jarring effect that a more distant modulation could have brought. Furthermore, upon the repeat, the return and perfect cadence in B-minor finish the piece off. Bach, therefore, easily doubles the length of this movement, gives us a chance to hear the ideas twice, and encloses them in a complete sounding form and progression.

The table below is a reduction to highlight my point regarding the economy of the Binary design that Bach deploys in Badinerie. He does use further modulations, which we will discuss, within each section of the work.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up for our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

Tonal Tactics and Smaller Scale Modulations (Harmony)

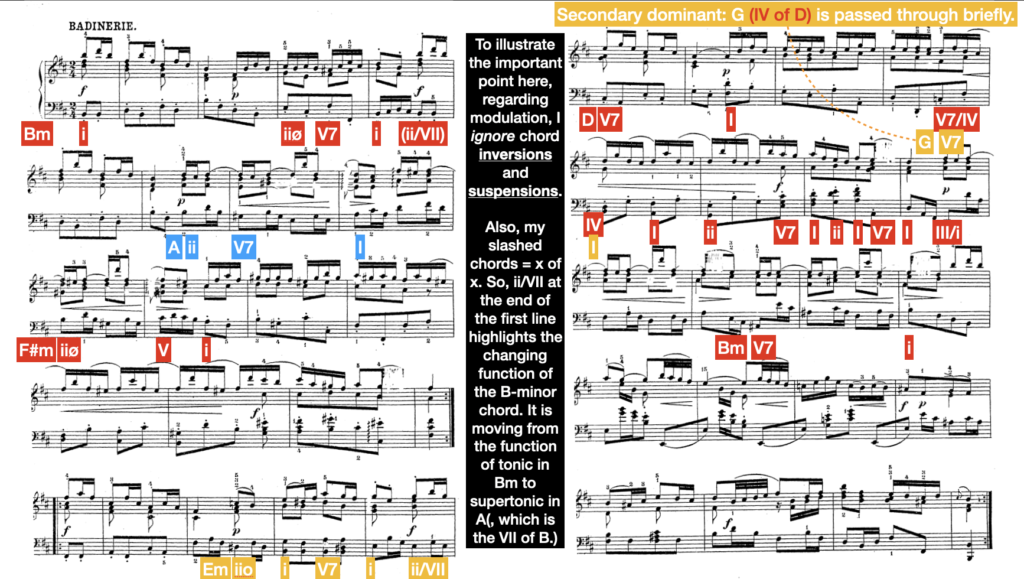

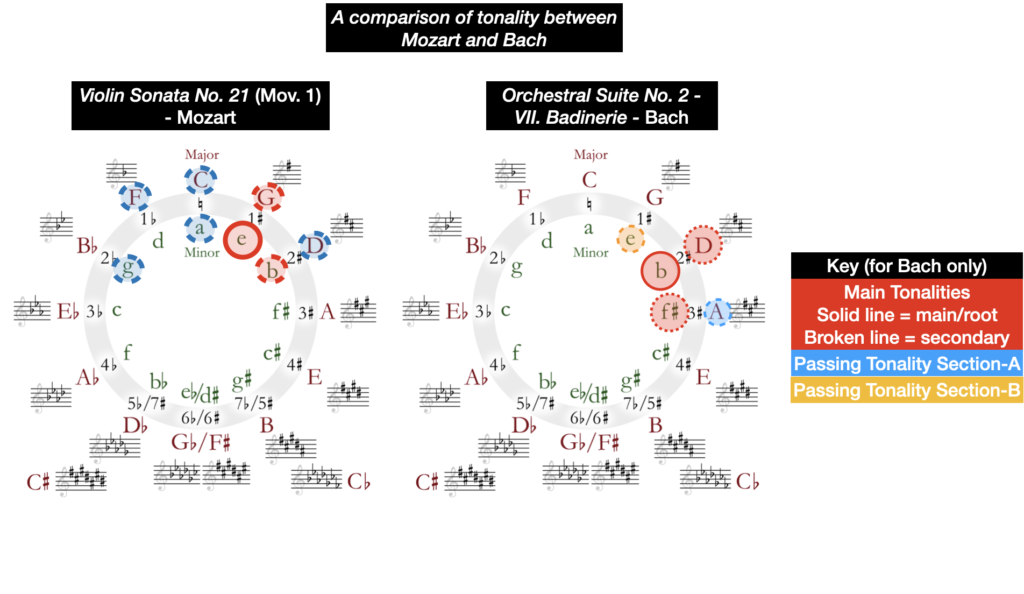

To reduce the Badinerie to a simple exchange of i – v – i (or B-minor – F#-minor – B-minor) is valuable on a larger scale regarding its Binary form. However, it misses out on several harmonic and tonal details within each section. For example, Bach exploits an incredibly interesting harmonic device that allows him to modulate seamlessly. The technique, used several times, involves the appropriation of the tonic, in the previous phrase, as supertonic in the next.

Limited by style and the harmonic structures inherent within that style, Bach can only use this device when modulating to a major tonality, due to the harmonic quality of the supertonic, in major keys, being a minor chord. For example, from bar-3 to 4 (counting the anacrusis bar as 0), there is a perfect cadence in B-minor. Over the next few bars (4-6), the chord does not change other than for inversions. Only at bar 7 does the harmony change to an E7 chord. Ignoring the suspension, this resolves as a perfect cadence to A-major. Contextually, between the two opening phrases, therefore, the function of the B-minor has gone from tonic to pre-dominant. In this instance, a pre-dominant chord in the form of a super-tonic: an ii in a wider ii-V-I progression.

Bach repeats this procedure in the second section of this piece, where he modulates to D-major. Having used a similar technique to tonicise E-minor, in bar 20, diminishing the preceding tonic F#, E-minor quickly becomes the supertonic for a modulation to D-major at bar 22. As the old adage goes: “if it ain’t broken, you can’t fix it.” In crafting a piece, why not use a useful device multiple times?

*Side note: “Tonicisation” is, basically, the imposition of a new tonic. To fully modulate the music must have a new tonic chord, at least for a moment. Around this tonic chord, particularly in the Western Common Practice tradition, the hierarchy of chords will also change. That is why using a ii-V-I (or iio-V-i in minor) progression is a good indicator of a new tonic, especially if the V is a V7, as the notes and chord structures are unique to the scale of that tonic. Essentially, it could be defined as a perfect cadence in a different key from the overarching one of the piece. (Although this is not the only way to tonicise a harmony/tonality…)

Tonal Area and Distance

Lastly (and briefly), it can be helpful to look at the tonal expanse of this composition from a different perspective. Doing so will give us an idea of Bach’s thinking and an increased sensitivity to aspects of style during this time.

The prevailing harmonic relationship of tonic and dominant, which we attribute most strongly to the classical period, did not appear overnight. It was emerging through the life of Bach. If we take, for example, the circle of 5ths annotation I made of Mozart’s E-Minor Violin Sonata (no. 21), we can see how close the keys Mozart uses are. Compare this to Bach’s Badinerie, and the tale is of even closer related keys.

Of course, Mozart’s composition is longer in this instance and aesthetically much different with regards to formal procedures. So, it makes sense that Bach’s tonal adventures in Badinerie are going to be more limited. However, the important take away here is that the harmonic relationship of the 5th was important to Bach, as it was Mozart.

Large Scale Thematic Relationships and Binary From

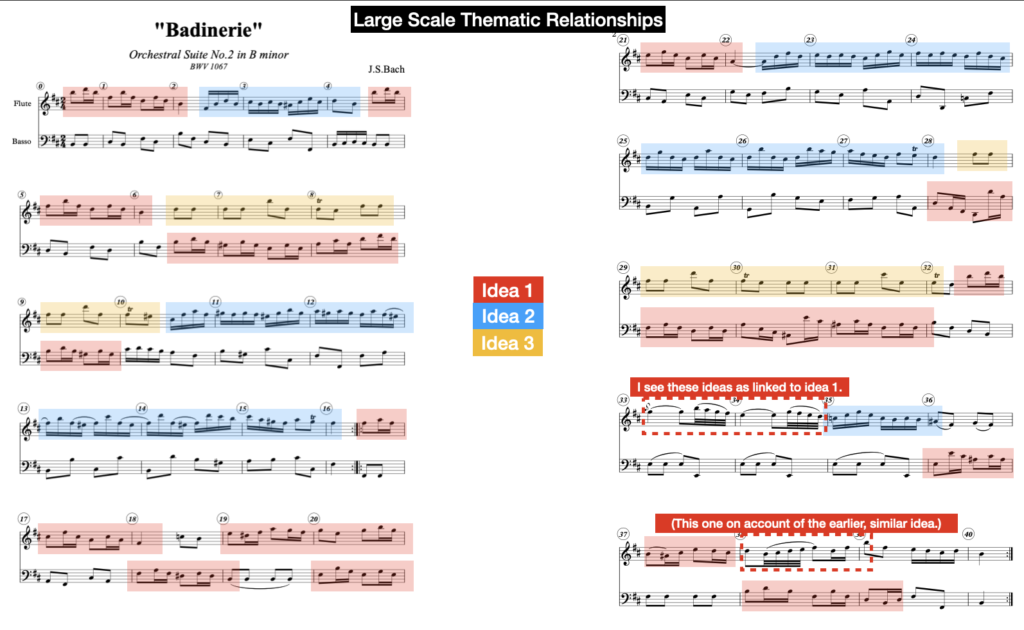

Before breaking down the small motivic units that Bach uses to create this composition, some larger-scale relationships are worth highlighting. Especially when Binary form, defined as an A followed by a B section, often leads to the misinterpretation that a composer has an A and a separate B idea. While the composer may have multiple ideas and may present them as A and B ideas across the relevant sections, that is not the case with Badinerie.

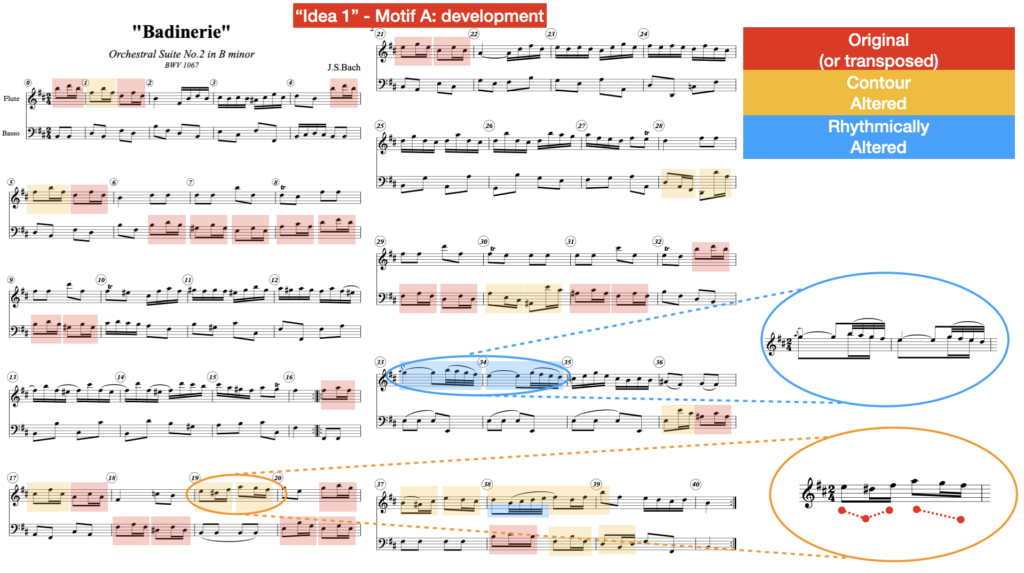

On a larger scale, the thematic material is insanely concise and is exposed very early in the piece. The example below demonstrates this by colouring all the parts of the score that use a reoccurring idea, in some form or other. Two main ideas (Red and Blue) undergo the most variation, while a third idea reoccurs in a slightly different form across each section of the composition. Ironically, despite being arguably less significant, it’s the repetition of the third idea that I, personally, find most remarkable and quintessentially Bach. Like ringing the last bits of water from a nearly dry cloth, why let a good idea go to waste?! Or, why come up with another idea if you already have something to draw upon already? Save your energy! In replicating idea 3, Bach does not need to come up with more than he needs to.

Instead of the AABB design corresponding to thematic material, it corresponds to repeated sections and tonal procedures (that we have already discussed). Section A is a movement of tonic to dominant; section B is the reverse (dominant to tonic). In terms of melody, there are two core ideas (idea 1 and 2) that form the basis of the piece. However, both ideas are used in each section of the work, following a similar order in each part.

Breaking down and understanding idea 1 and its variants

Idea 1 is incredibly simple. Characterised by a quaver, semi-quaver and semi-quaver rhythmic cell, it often uses chord tones, emphasising the underlying harmony. Doing this gives the cell an incredible amount of elasticity as it can be adapted to fit its harmonic contexts very easily. Especially, given Bach is using triadic harmony, concurrent with the Baroque musical style.

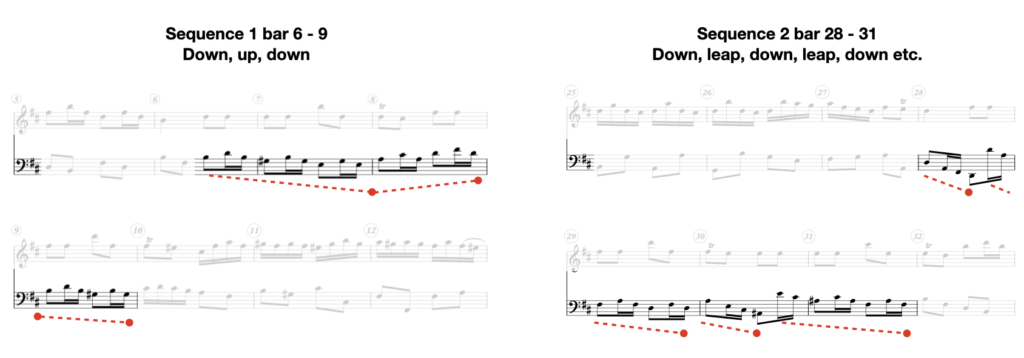

These short melodic cells tend to be strung together into short melodic sequences that follow a downward trajectory. However, many variants also go upwards or form larger complex contours too. For example, from bar 6 to bar 9, Bach strings together 7 of these cells. He creates a down, up, down shape. Similarly, creating another sequence from bar 28, again in the bass, Bach creates a pattern that works downwards before jumping abruptly upwards and then down again. He uses 8 cells in this instance.

Other means of variation (idea 1)

Stringing together melodic cells in this instance, altering the trajectory they take, is not the only means of development Bach imposes on this idea. Bach also uses two other methods to vary idea 1: (1) altering the contour [orange] and (2) rhythmic alteration and embellishment [blue].

The contour changes are the simplest that Bach applies to the melodic cells, which are similar to how he adapts his sequential strings of cells. For instance, bar 19 features an inverted version of idea 1’s core melodic cell. Instead of going up then down, it forms a “V” shape. The second cell alters the shape more dramatically. It not only goes downward but does so via stepwise intervals.

The rhythmic alterations are more dramatic and are limited to bars 33 and 34. (Bar 38 also has similarities to these but also features contour changes.) How, though, does this idea relate to the earlier cell? It does so through its contour and overall shape. Note how both cells skip upwards by a 3rd, similar to how they do in the opening cell in bar 0. Furthermore, they come back down too, falling by a 3rd to the next cell. The primary differences are that the first note value is augmented to a tied crotchet and quaver length value. Then, Bach uses demi-semi-quavers, filling in the gaps by stepwise downward motion.

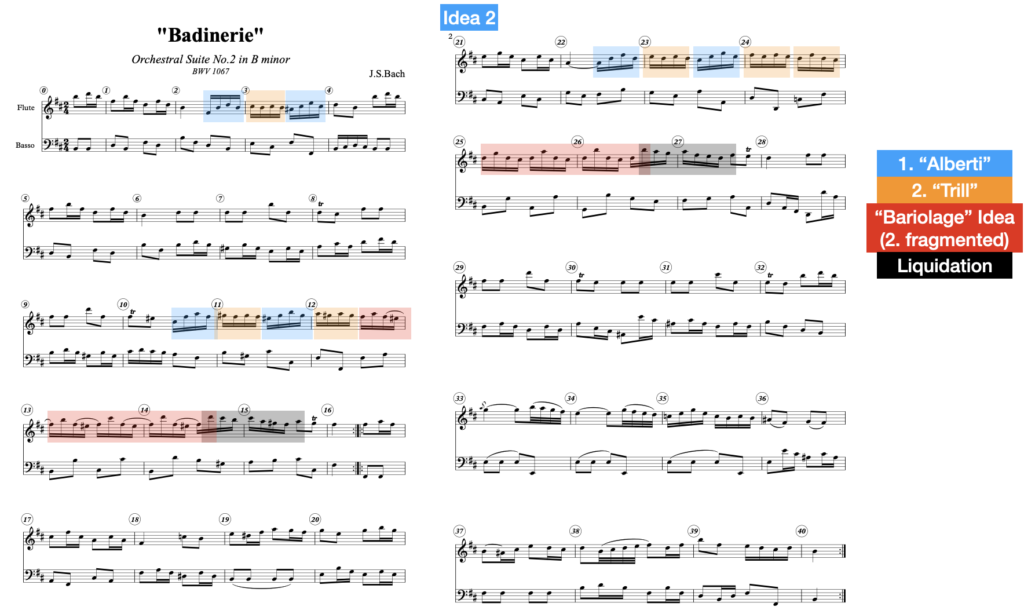

Breaking down and understanding Idea 2

Idea two is more expansive than idea 1, comprising two different melodic cells. The first of these is similar to idea 1 in that it outlines the underlying harmony. However, it does so in a wholly semi-quaver rhythm, with a shape reminiscent of Alberti bass. The second cell is an oscillating idea that could be described as a semi-quaver trill.

Similar to idea 1, one way in which Bach adapts and extends this idea is through sequences. In bar 11 – 12 and 22 – 24, Bach places two pairs of these cells together, one after the other. Nonetheless, unlike idea 1, he takes developments of this idea in a different direction and, arguably, one step further.

The “Bariolage” idea: fragmentation and liquidation

Shortly after the two phrases (11-12; 22 – 24) that I highlight in the previous paragraph, the Badinerie breaks out into two climactic moments. Although strictly incorrect, I liken the passage to the bariolage technique, where (typically) a string player oscillates between a repeated note and different melodic material. Often using an open string, the technique can enable the music to jump between larger registers quickly. In this instance, the repeated note is the fragmented “trill” cell, which is played against a rising, higher pitch. In this instance, it has the effect of raising excitement levels.

As mentioned, a developmental technique that Bach uses here is fragmentation. Fragmentation is where a smaller portion of the motif or cell is used on its own and possibly developed further. In this instance, as we have seen, Bach uses fragmentation to develop his material, allowing him to string together several cells that vary each time through the rising upper note of the “bariolage” idea.

In isolation, the fragmented cell is distinct from its whole. In describing the original as a trill, now it is more an inverted mordent. Stepping away from the original idea and building to a climax, Bach breaks the tension by liquidating his idea. Maintaining only the semi-quaver rhythmic momentum, the flute part’s melodic material (in both 14-15 and 26-27) momentarily reflects very little of the preceding material.

Liquidation is the process of “eliminating characteristic features” (Schoenberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 1967:58). Here the process involves the trill motif, which was fragmented. Replacing its final note with a rising melody, it is similar but distinct from the original motif. At the very end, none of the intervallic content or oscillating (“trill”) shape remains, only the semiquaver rhythm. Retrospectively the fragmentation of the melody, through the “bariolage” passage, was a step of this process.

Here is a video for anyone interested in hearing more about Bariolage and how it is performed on violin.

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Close

The term craftsman is disparaged all too readily, in my opinion, especially when we are discussing canonised musical compositions or composers. However, I think we do ourselves a great disservice by simply admiring Bach as an artist alone, elevating to a form of divine status. There is no question that he was prolific and composed many great and moving works. However, he was a human person. The only way to be so prolific, meeting the demands of his job as a composer, was to develop crafty skills.

Bach’s demonstration of well-oiled, craftsman techniques is invaluable to us here, analysing his work as composers. While the finer details may be less valuable to us, requiring stylistic reappropriation, they remain relevant on a fundamental and broader level. For example, we can use fragmentation and contour to develop any musical cell. We can even think in terms of musical cells! We can also redeploy harmonic devices that we like or deem effective, in different contexts, across or within musical compositions. In essence, we can all become craftier.