METROPOLIS / Film by Fritz Lang, based on a story by Thea von Harbou / Alfred Abel (Joh Frederson); Gustav Fröhlich (Freder); Brigitte Helm (Maria); Theodor Loos (Josephat); Rudolf Klein-Rogge (Rotwang); Fritz Rasp (The Thin Man); Heinrich George (Grot); Erwin Biswanger (Worker 11811, Gyorgy) / Music by Gottfried Huppertz / available for free streaming on YouTube

Fritz Lang

I never review or comment on films because, for the most part, I find artificial, created drama which does not stem from a real situation to be superfluous and rather silly, but I am making an exception in the case of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis because its very imagery is artistic. From first frame to last, juxtaposing harsh, gritty reality with fantastic scenes, luxury and even science fiction, Metropolis is in my view the single greatest masterpiece of the Art Deco movement…in fact, it is Art Deco and Bauhaus architecture come to life and set in motion. Despite the sometimes heavy-handedness of its philosophical message, apropos at the time but certainly passé since the days of trade unions, the 40-hour work week and built-in vacation and sick time, Metropolis certainly brings into stark focus a nightmare world of capitalism run berserk, where workers live in dark drudgery beneath the earth’s surface while their wealthy, upper-class overlords benefit from their toil without seeing, knowing or caring how they exist.

Metropolis was a moment in time, the brainchild of Lang’s wife of the time, Thea von Harbou. Her novelette, which preceded the production of the film, went even further in its science fiction allusions, including a trip into space in a rocket ship for Freder at the end. Yet what Lang did with the film was so startling, and in many ways so far ahead of its time, that few if any modern (post-1960) viewers can help but be moved and awed by it.

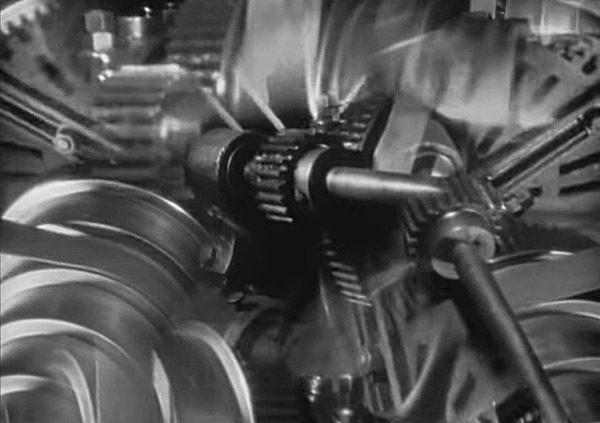

The Machines

As suggested by my comments in the first paragraph, Metropolis was an expressionist morality play. In a non-specific future time there exists a super-city in which airplanes rival cars as a means of transportation and both huge sporting arenas and pleasure palaces reign supreme. This is Metropolis, a city run with an iron first by Joh Frederson, pretty much all by himself. He communicates to his workers through an assistant, Josephat, who in turn communicates with Grot, the foreman of the Heart Machine that is at the center of everything. The workers’ city is “deep below the earth’s surface,” only accessible by large, multi-person elevators. We then see the huge, clean arena in which the sons of the wealthy engage in sporting events on a daily basis, and it is here that we meet Freder Frederson, Joh’s son. In the midst of one of his revelries, a strange woman leading a large group of children appears. This is Maria, the “angel” of the workers, who has brought their children to the surface to see how their “brothers and sisters” live. Freder is smitten by Maria’s beauty and sweet, open nature, and her visit prompts him to go to the workers’ city to check things out for himself. There, he volunteers to switch places at the gigantic Heart Machine with an exhausted worker, number 11811, whose name is Gyorgy. In the meantime, his father learns from Grot, the foreman, that his workers have been passing around strange little maps to each other. Angry that his go-between with the workers, Josephat, did not know this and tell it to him, Frederson fires him and consigns him to disgrace. Freder, however, befriends him and promises to report back to him what is really going on in the workers’ city. Seeing this interaction between Freder and Josephat, Joh Frederson instructs his toady, known only as The Thin Man, to shadow Freder at all times.

Freder working the Heart Machine

Joh Frederson then visits the laboratory of the brilliant but mad scientist Rotwang for advice on this situation. Rotwang was the father of Hel, formerly Frederson’s wife, who died in childbirth while delivering his son Freder. Rotwang secretly hates Frederson for this though he promises to advise him. He shows him his latest creation, a life-sized, lifelike robot, and then interprets the maps as being of 2000-year-old catacombs beneath the workers’ city. He leads Frederson down there, where they witness Maria speaking to the workers of the Tower of Babel and how it was built by near-slave labor, like themselves, directed by men who did not communicate with them. “The mediator between the Head and the Hands must be the Heart,” she tells them, and promises that someday that mediator will come. Freder is in the crowd watching her, and afterwards he goes up to her, promises to be that mediator, and kisses her.

Shift change.

But Frederson has other plans. He directs Rotwang to give the robot the likeness of Maria and to sow discord among the workers. Rotwang does reshape the robot as Maria but takes it much further. She not only sows discord, but goads them into smashing the Heart Machine because their mediator has not come. In doing so, the workers’ city becomes flooded and the real Maria, along with Freder, madly scramble to rescue the children.

Joh Frederson, Rotwang and the Robot

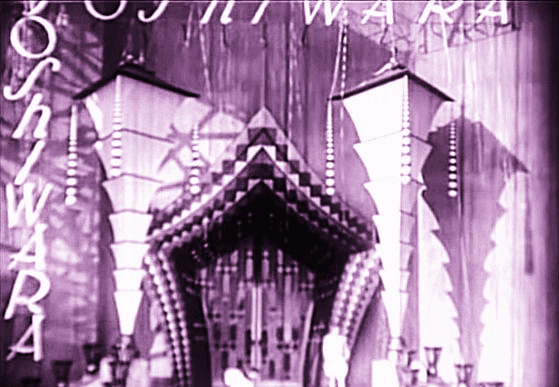

The movie has an Interlude in which we see the false Maria dancing half-naked in a nightclub for the wealthy called Yoshiwara, and also Freder in the catacombs talking to the Seven Deadly Sins. In the end, Grot rouses the workers to capture and kill Maria for her treachery, which they do; Freder tries to save her, but to no avail—she is burned at the stake. Spoiler alert: the Maria burned at the stake turns out to be the robot. The real Maria, trapped in Rotwang’s house, is being stalked by him to turn her into “the new Hel.” Freder chases Rotwang onto the roof of his house, has a fight to the death with him, wins and saves Maria. At the end, he does indeed act as the mediator “between the Head and the Hands” as he convinces his father to shake hands with Grot.

At the very beginning of the film we see the “shift change,” and this is one of two errors that the normally meticulous Lang made. Since the machines must always be kept running, it would be disastrous for every worker down below to leave their post and rise to the upper level, get off their elevators, then wait for the new shift to walk onto the elevators and descend to the depths to begin work, but that is what happens. The other error occurs later on when Rotwang leads Frederson into the catacombs. Supposedly beneath the workers’ city, which is in turn “deep below the surface of the earth,” the pair simply walks down two flights of steps and there they are!

Rotwang’s laboratory

The robot being converted into Maria’s likeness

Being done by a German, this story was of necessity dragged out, the original film running about 153 minutes. This also made it one of the longest films of its time, rivaling Abel Gance’s equally groundbreaking Napoleon of the same year. Yet since most audiences wouldn’t sit still that long, it was almost immediately cut down in size even in Germany. When it reached America, where it was leased through Paramount Pictures, it was not only reduced still further to 116 minutes, but the scenes that remained were rearranged to make the workers out to be the villains rather than the victims. Lang was so incensed that he refused to see this copy of the film, and never did.

Yoshiwara

The false Maria lecturing the workers

The workers’ city is flooded

Although both audiences and film critics enthusiastically applauded the film’s most spectacular scenes, many panned it as pretentious and overlong. H.G. Wells, the famed science fiction writer, wrote a review in April 1927 accusing it of “foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general.” He faulted Metropolis for its premise that automation created drudgery rather than relieving it. One of the reasons why Paramount insisted on changing the story was, according to playwright Channing Pollack who did the job, because “symbolism ran such riot that people who saw it couldn’t tell what the picture was about. … I have given it my meaning.” Among his changes were to remove all references to Hel because the name sounded too much like Hell and he thought American audiences would be offended. Needless to say, American critics panned in unmercifully.

But the Nazis were enthusiastic fans of the movie! Joseph Goebbels raved about the film’s message of Social Justice, saying in a 1928 speech that “the political bourgeoisie is about to leave the stage of history. In its place advance the oppressed producers of the head and hand, the forces of Labor, to begin their historical mission.” Shortly after the Nazis came to power in 1933, Hitler, who had also seen the film in 1927, said that he wanted Lang to make Nazi films. Being half-Jewish, however, and having a brain in his head, Lang left Germany and never returned. In his later years, Lang said that he thought Metropolis was “a lot of nonsense,” but those close to him acknowledged that this opinion was given in part because of the Nazis’ endorsement of the film.

Metropolis at night

Yet, as I said, watching the film is still an emotional and often mind-boggling experience, especially when you consider that this was made in 1927. In addition, Lang rarely used doubles even for the most dangerous scenes—that really is Brigitte Helm forced to wear that robot suit in which she could scarcely breathe and really her being burned at the stake, really Gustav Fröhlich fighting for his life on the rooftop of Rotwang’s house, and really all of those extras on the verge of drowning in the flood of the workers’ city—which gave this “fantastic” film the feel of realism. Yet as I say, in the end it is the visual aspect of the movie, the almost unending sequence of artistic shots, that keeps you coming back to it.

The music for the film was written by Gottfried Huppertz in a style emulating Richard Strauss and Erich Wolfgang Korngold. It is very Romantic and a bit over-the-top, but it works. Alas, it was only heard once in its time, at the movie’s premiere in January 1927. After that, it disappeared until 2001 when the score was discovered and used for a screening. But the biggest breakthrough came in July 2008, when a nearly-complete print of the film was discovered in Buenos Aires. Only one or two short scenes were missing. The challenge of integrating the missing scenes into the existing print of the complete movie was that this surviving print was on nitrate stock, which had disintegrated badly, and was in 16 mm. Nevertheless, expert film editors managed to salvage it and splice it in mostly without being noticed, except that the replacement footage has a grainy quality about it that could not completely be cleaned up. When a new print was created in 2010, Huppertz’ score was restored—but gone now were the color-tinted scenes that had been part of the film from its inception. Granted, the scenes in the depths of the workers’ city were, and rightly remained, in black-and-white, but several of the aboveground scenes in Metropolis were tinted: sepia, blue and occasionally pink. This gave the film an even more fantastic look which is now gone because all of it is in black and white.

But even in black and white, it is an awe-inspiring experience, one that you’ll never forget and will probably re-watch because it IS so good, the one film in my experience that is morality play, entertainment and great visual art all rolled into one.

—© 2020 Lynn René Bayley

Follow me on Twitter (@Artmusiclounge) or Facebook (as Monique Musique)