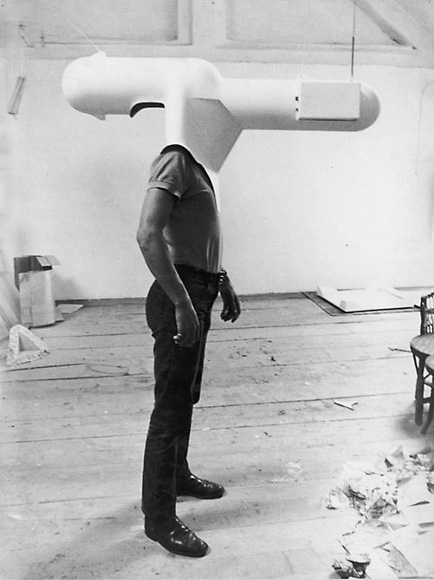

TV-Helmet (Portable living room), 1967

Prototypes, a series of sculptures made in the ’60s by Walter Pichler, explore the overlap of architecture/design/sculpture. The materials (polyester, Plexiglas, PVC, aluminum, inflatable elements) used by the Austrian artist were new at the time.

Around forty-five years ago a man wore a submarine-like white helmet that extended from front to back. His entire head disappeared into the futurist capsule; only the title betraying what was happening. TV Helmet created in 1967 is a technical device that isolates the user while imbedding him or her in an endless web of information: closed off against the outside world, the wearer was completely focused on the screen before his eyes.

TV Helmet is the work of Walter Pichler and it doesn’t merely formally anticipate the cyber glasses developed decades later; Pichler also articulated questions of content in relation to the media experience long before the “virtual world” was even discovered. Even back then, Walter Pichler was probably already a media critic as he’s remained one to this day. But he is also a conceptually thinking artist who explored space early on—beyond the four walls and the structures of cities. Pichler called his invention a Portable Living Room. His pioneering designs, The Prototypes, are pneumatic plastic living bubbles from the sixties that sought answers to the questions of tomorrow’s individualized life somewhere between the areas of design, architecture, and art. With their reference to space travel and modernist materials, Pichler’s futurist sculptures inspire a desire for the future— even if his messages are said to possess a sceptical or sarcastic undertone.

Walter Pichler, Drawing for “Intensivbox,” 1967

Pichler wrote these words in 1962, on the eve of an exhibition on which he collaborated with fellow Viennese architect Hans Hollein.

“(Architecture) is born of the most powerful thoughts. For men it will be a compulsion, they will stifle in it or they will live – live, as I mean the word … (Architecture) has no consideration for stupidity and weakness. It never serves. It crushes those who cannot bear it… Machines have taken possession of [architecture] and human beings are now merely tolerated in its domain. “

A statement of singular nihilism, unabashed iconoclasm; a statement Ulrich Conrads once called “the most absolute thesis” in all twentieth century architecture. In the sixties, after studying at the Hochschule für Architektur in Vienna, he worked with his friend, the internationally renowned architect Hans Hollein, on a new concept of architecture. In 1963, the two exhibited together at the Galerie nächst St. Stephan under the title Architecture. Hollein and he explored utopian architectonic designs; they countered the growing subdivision of the city with a larger modernist vision made from cement, declaring architecture “freed from the constraints of building.”

For Pichler, media are far from participatory but instead somnambulating and hypnotizing, pulling humanity’s attention away from its greatest attributes. Likewise, instead of making human abilities more numerous, like prosthetics, the Portable Living Room and Small Room disable a subject from moving with their usual acuity. Unlike the other helmets designed by his Viennese contemporaries, Pichler’s don’t provide more experience or more engagement, but instead subtract. It’s terribly ironic, therefore, that Pichler subtitles his piece “Portable Living Room,” because it is certainly not portable, and at best a shoddy simulation of a living room. The Portable Living Room enables a person to remain motionless, separating them from their obligations and necessities to simply be entertained. Like a visionary anticipating the arrival of the ‘couch potato’, Pichler saw media not as enabling but disabling, entrapping, enabling of nothing more than laziness.

Walter Pilcher, Small Room Prototype no.4, 1967

Pichler’s exhibition on which he collaborated with fellow Viennese architect Hans Hollein entitled “Absolute Architecture,” added two new voices to the growing chorus of dissent aimed at derailing architectural functionalism. For Pichler and Hollein, architecture was not what it enables, nor what in encloses, but what it is. Architecture is a thing, and it can take whatever form an architect wishes. Given this seemingly impossible assignment, Pichler and Hollein developed a series of underground buildings, modeled in bronze and concrete. These underground environments were to have extensive environmental controls so that their position underground would not matter. Though the weight of these first models ended with “Absolute Architecture,” both Pichler and Hollein recycled their conceptual bases in subsequent investigations.

For Hollein, this took the form of literal environmental simulators like his Non-Physical Environment Pill(1967) and later Svobodair Spray (1971), both of which were hypothetical propositions about the power of environmental simulation. Pichler also experimented with such hypotheses in the late sixties, most transparently in the works of his “Prototypes” exhibition of 1967. These strange objects critique new media’s ability to induce laziness and atrophy. Three of these works in particular—TV Helmet/Portable Living Room, Small Room, and Intensivbox—form a kind of suite, all taking roughly the form of an isolation chamber and including media inputs. For Pichler, it seems, media isn’t architecture, hence he makes it architecture by creating armatures to embody its physical presence.

TV Helmet/Portable Living Room (1967) and Small Room (1967) are to be worn, while the unrealized Intensivbox is a spherical chamber into which a subject is slid on a track. These isolating simulators remove one from a given reality and can be seen as the ultimate conclusion of technology’s encroachment on the body. Constructed of plastic and embedded with television sets and speakers, these helmets enhance the television experience to the detriment of all else. Pichler hoped to isolate and insulate himself (and his viewers) from the pitfalls of consumerism and media obsession, but in his helmets this took the form of a literal representation of such pitfalls. The “consumer” is isolated from her environment, but within the helmet only media are permitted as input. These works can are also a critique of his one-time collaborator Hans Hollein’s ironic assertion that “everything is architecture.”

Walter Pichler, Schädeldecke, Selbstportrait (mit Spiegel), 2004

Courtesy of Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Pichler’s concerns mirror those of German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s in his essay “The Question Concerning Technology.” Like Heidegger, Pichler retains a rigorous scepticism towards technology. Speaking of techne, Heidegger writes, “Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it. But we are delivered over to it in the worst possible way when we regard it as something neutral. Pichler’s provocation is that if one lets media (or technology more generally) isolate and insulate, it will be to the detriment of other abilities. If a helmet is a Portable Living Room, it means the only important part of the room is the television.

In his media-theoretical standard work “Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man”, which was published in Germany one year after Pichler exhibited his TV helmet, Marshall McLuhan famously declared that “the medium is the message.” At first, McLuhan was interpreted in just as one-dimensional a way: the culturally pessimistic interpretation of his thesis was that the technical device is so powerful that it even functioned without content. Stupidity, social and physical disorders, conformism seemed inevitable. Yet McLuhan as it turns out, was far more sober observer and affirmative analyzer.

Instead of a destruction of the technology he demonizes, Pichler constructs ridiculous analogs to their abilities. If television provides a subtle escape from the ordinary, Pichler’s helmets enhance this ability to the point of absurdity. Pichler’s environmental simulators aren’t portable, and in fact limit one’s range of motion quite significantly. Portable Living Room is the best illustration of this fact, its elaborate counterweighted system protruding from both sides of the subject’s head obtrusively. It doesn’t fold, doesn’t retract, and doesn’t provide anything but sensory input. One puts it on because of a desire to be isolated. With his “Prototypes,” Pichler definitively states an interest in isolation, a concern that would come to dominate his career thereafter. It is almost as if he is rehearsing a retreat, one that would come to fruition in the mid-seventies, when Pichler himself retreated from public life to his property at St. Martin’s in the Tyrol region of western Austria. Returning only to exhibit and to sell his drawings, Pichler remains free to explore and create at his own pace and in his own idiom. These drawing sales have funded an increasingly isolated practice, concerned with sculpting and with constructing ever-more-complex armatures and environments for said sculptures.

Perhaps calling his buildings environments sells short his activity. His constructs are worlds, worlds in which his work is isolated from both critique and the media-obsessed culture it critiques. They are in fact alternate—but not virtual—realities in which his work can remain indefinitely. The “Prototypes” can also be thought of as such. More than mere simulators or enhancers, they offer the subject another world to inhabit, portable or otherwise. Pichler must have imagined himself within them, isolated from the laborious requirements of contemporary life. But ultimately this subtle escape wasn’t enough, leading Pichler back to the Tyrolean Alps, free from his obligations in Vienna and free to investigate the kind of craft- and skill-based sculptural techniques he felt technology would eventually preclude.

Up until the present, Walter Pichler’s architectonic drawings and sculptures have been characterized by a thought process that crosses the borders between disciplines. For his hominid sculptures of metal and wood, he built his own exhibition spaces that were somewhere between a temple and a container. And they never depart from them: Pichler regards this interplay between space and object as crucial. The one would never be complete without the other. One has to go there to see them. And he, too, for the most part shuns the art establishment public. Pichler has been considered one of Austria’s most important contemporary artists, although he preferred not be. “I haven’t wished to be called an artist for a long time now,” he told the newspaper Zeit a few years ago, which visited him on the occasion of a Berlin exhibition at the Contemporary Fine Arts Gallery in his country home in St. Martin in the far reaches of Burgenland. “Most people aren’t interested in anything but getting rich and famous.”

Pichler had solo exhibitions at Whitechapel Gallery, London; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; and Stadelschen Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt. He represented Austria in the 1982 Venice Biennale and participated in Documenta 4 and the fifth Paris Bienniale, both in 1968. Many of Pichler’s works are owned by the Deutsche Bank Collection. The 1996 exhibition “Joseph Beuys / Walter Pichler Drawings,” conceived by Deutsche Bank, juxtaposed a significant group of Beuys drawings with paper works by the 1936-born Austrian.

Since the 1960s, Walter Pichler has worked in the borderline area between sculpture and architecture, designing models of utopian cities and objects. Walter Pichler passed away in his home at the age of 76 in July 2012.

Hmm it looks like your blog ate my first comment (it was super long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly

enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any recommendations for newbie blog writers? I’d really

appreciate it.

Pingback: Mobilya ofis buro | The TV Helmet

Hands down, Apple’s app store wins by a mile. It’s a huge selection of all sorts of apps vs a rather sad selection of a handful for Zune. Microsoft has plans, especially in the realm of games, but I’m not sure I’d want to bet on the future if this aspect is important to you. The iPod is a much better choice in that case.

Pingback: These Rare Historic Photos Show Extraordinary Practices In The 1900s

Pingback: The 24 Rarest Historical Photos That Will Leave You Completly Speechless

Pingback: 8 Rare Historical Photos That Will Leave You Speechless

Pingback: Speculative design – projects | Play Lab

Pingback: 24 Rare Historical Photos That Will Leave You Absolutely Speechless

“Walter Pilcher, Small Room Prototype no.4, 1967”

The indvidualised matrix is real!