Editorials

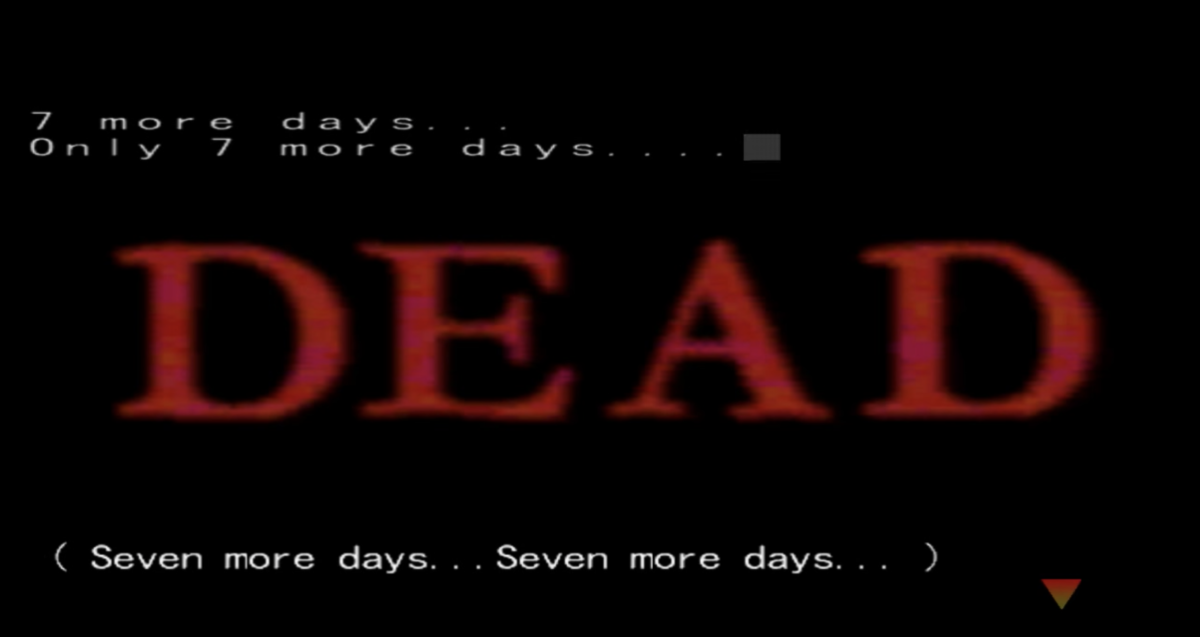

[Based on the Hit Film] We (Barely) Survive the Highly Unknown ‘Ring/Ringu’ Dreamcast Game

We endure the awful Dreamcast survival horror game that’s based upon ‘The Ring’ series, the perplexing disaster, ‘The Ring: Terror’s Realm’.

“[RING], a killer computer program? It’s silly, but it makes me wonder…”

Sometimes a horror franchise hits such a fever pitch that it’s able to make the transition over to other media, like video games. This isn’t always an easy process and obviously, some titles, such as slashers, lend themselves more to the survival horror video game genre than other films. That being said, this is still a relatively rare experience and even horror’s heaviest hitters haven’t gotten truly worthy video games until very recently. That’s what makes Asmik Ace Entertainment’s Dreamcast title, The Ring: Terror’s Realm, such a fascinating project. Hideo Nakata’s Ringu is absolutely not the title you expect to transition over to video games (unless it maybe crossed over with the Fatal Frame series). That’s not to say that it’s an impossible prospect and “J-horror” could certainly use more representation in video games, but unfortunately, The Ring: Terror’s Realm is one of the absolute worst games to come out for the system.

One of the biggest surprises about this property is that it came out for the Dreamcast in 2000, which means that it actually pre-dates Gore Verbinski’s American The Ring by two years. This title actually draws most of its lore and inspiration from Koji Suzuki’s series of Ring novels, even though it includes footage from the Japanese films. The game came out in Japan a month after the release of Ring 0: Birthday and was surely meant to piggyback off of its publicity, but the decision by Infogrames to localize this title for North America comes as a major surprise. At this point in time, America has no relationship with this franchise, let alone “J-horror” in general. Clearly, Infogrames thought that any survival horror on the system could draw big numbers, especially when Resident Evil Code: VERONICA was so hot, but The Ring: Terror’s Realm is a complete disaster on every level, but it’s at least a bewildering train wreck to work through.

The Ring: Terror’s Realm centers around Meg Rainman, a scientist at the CDC who’s on her mission after the cursed “[RING]” game kills her boyfriend, Robert. Meg quickly learns that he’s not the only one to recently die under these suspicious circumstances. After Meg experiences the [RING] game, the CDC becomes under quarantine, which ostensibly keeps her in there for the whole game as she attempts to solve this mystery before her expiration date is up. It comes as a major shock when Meg boots up [RING] and she’s not greeted with a creepy video, but is instead transported into a Tron-esque world like some Sentai Ranger. It’s a bold turn, one that doesn’t make any sense, and something that feels like it would be much better suited in anything else that’s not a video game based on The Ring.

These segments of the game force Meg to navigate via flashlight through dark corridors. These moments of vulnerability have an admirable look to them and you can tell what they’re going for, but they get bland very quickly and feel like they belong in another title. The monsters themselves look like Neanderthals of some type, and again, nothing that specifically screams Ring. Apparently, Sadako’s powers turn people into monkey monsters this time around, too. These beasts also provide zero challenge, especially when ammo is of no real concern here. Even if a bunch of Sadakos were the generic enemy, they’d still be scarier than the alternative. The game switches back and forth between these two worlds, but a major issue is that this “action horror world” is only marginally more suspenseful than the drab CDC segments. The lighting is the creepiest thing. A little variety in the enemies would also go a long ways, but the game sticks to their manbearpig model.

Subtlety is far from the game’s strong suit and characters will just arbitrarily contact you, but you have no idea or context for who they are. None of this matters because they’re just meant to give you exposition and apparently it’s more entertaining to read this through dialogue from someone named “Jack” than off of a document on a table or something, even though there’s no difference in how the game presents this. This lack of personality is present across the board, which is kind of shocking. Everything just feels like it’s there to help move the plot along, not even to scare the gamer, which would at least make this more tolerable. Terror’s Realm is so void of flavor that you could honestly fall asleep while playing it. It’s easily the worst survival horror title on the Dreamcast (and there are some forgettable ones, like Carrier). Notoriously, the game’s review on GameSpy’s DreamcastPlanet was a 1/10 and the title nearly broke the reviewer.

The Ring: Terror’s Realm actually decides to recap the events of Ringu that go all the way back to 1990 and act as a brief primer on Sadako Yamamura’s tortured life. There are allusions to the novel that inspired the films and even footage from them, but the game still barely connects to the canon. Nevertheless, Terror’s Realm discusses how the infamous Sadako videotape has evolved into a virus, which then worked itself into the [RING] video game. This plot is also much more in line with the novels’ take on Sadako, where she’s not a ghost, but rather her memories are transmitted via the cursed videotape.

The Ring: Terror’s Realm tries to get creative with its premise, but it could provide a better explanation as to why Sadako Yamamura does all of this and why she decides to move to the medium of video games. There are brief hints at answers to these questions, like how the CDC is apparently in possession of Sadako’s body, but then it moves into questionable territory where Sadako’s body is used to make a “vaccine” for her curse. That’s a physical vaccine for a spiritual curse. It doesn’t make any sense. This all builds to the revelation that Sadako has somehow built a virtual world that Meg gets stuck in, but to the game’s credit, The Matrix was pretty new at the time of its release.

Terror’s Realm doesn’t even let you find and watch the infamous cursed videotape until the final third of the game and even then it’s an extremely underwhelming experience. It’s appreciated to get a glimpse of this legendary footage from the original film (there are also snippets of Ring 2, with Sadako’s mother), but it also muddles the game’s message since it’s supposed to be a video game that’s now cursed. That doesn’t mean that footage of the old tape can’t still exist, but it feels pretty gratuitous, unless the idea is that Meg is now double cursed (which makes no sense). It’d be nice if after this point in the game Sadako would at least start following you around, but the gameplay or lack of enemy variety remains the same.

Finally, Meg learns that her trusted boss at the CDC is actually a bad guy and wants Sadako’s powers for himself. It’s also worth addressing that the final boss is Sadako, but you fight her with a katana. As you swing the mighty blade at her, she turns into bats, like Dracula, to evade your attacks because this is The Ring, after all. In the end, a very flimsy explanation is given to all of this where basically Sadako just despises that humans are able to do whatever they want and so all of this is some kind of bitter revenge. She wants all humans to die.

The Ring: Terror’s Realm is narratively a mess, but aesthetically and design-wise it’s not much better. Meg always has some kind of grin plastered on her face, like she’s the victim of the Joker’s nerve toxin. In fact, all of the characters have unintentionally unnerving models. Curiously, the game’s character designer is Katsuya Terada, who’s pretty renowned in both video games and anime for his characters, yet these just don’t click.

Basically, only the game’s introductory cut scene features dialogue and it contains some really abysmal voice acting performances. It almost makes you glad that the rest of the game just features text exchanges and no actual dialogue (which is still exceptionally lazy in a Dreamcast title). Additionally, Terror’s Realm contains a really irritating, lazy muzak-style soundtrack, which is not only not creepy, but it actively breaks the tension in the environment. It also starts over every time you go to the pause screen, which finds a way to make all of this even worse. On this note, the sound effects for the menu are all confusing splat sounds, which is just weird. It’s not that kind of game…

A lot of time in this game is spent aimlessly running around an area until you find the right door that will open to progress things along. This is more trial and error than any informed structure. It’s as if The Ring film never leaves its second act where Naomi Watts’ character is just in research and interview mode. Or do you remember that bit in the film where the item, healing jelly, is used to reduce the threat of Sadako? Of course not! This is all also just a very repetitive, fetch-y kind of survival horror title that’s more errands and unlocking drawers than scares and enemies. This slog should last you between six and seven hours, but it feels like there’s 45 minutes worth of content here.

There’s a very rudimentary combat in system in place that feels clunkier than the one present in the first Silent Hill. One the other hand, the title offers a surprising amount of freedom with its camera angles and it allows fixed camera angles, ones that follow you, or go the first- and third-person route. It’s just a shame the game isn’t good enough to actually make fun use of these options. It’s almost like it was added to make up for the fact that other areas in the game are lacking.

It’s painful to see how The Ring: Terror’s Realm intentionally apes Resident Evil in so many ways, like the limited inventory (which looks identical), but manages to make every case even less user-friendly. There are even item crates and freaking door-opening animations for scene transitions! You practically expect to save on a typewriter. Also, The Ring translates to some kind of detective story, not a horror-action title like Resident Evil. A survival horror game based on the Ring series could be great, but this goes completely in the wrong direction and squanders the property. It’s not surprising to learn that the game’s director, Atsushi Suzuki, has no other directing credits to his name and barely any other experience in the video game industry.

The Ring: Terror’s Realm desperately wants to be a Ring game, but then why make its connections to the source material so tangential? This could have just been titled Terror’s Realm and been its own thing to zero consequence. I mean, there are gas leak booby traps in this game that you have to figure out like you’re in Indiana Jones. It’s yet another element that feels completely foreign to The Ring series. On top of this, the title is filled with inner-office politics, a hair growth serum and smallpox scare, and a bunch of weird patients that are holed away in the basement of the CDC that never amounts to anything more than dull padding.

Besides a Wonderswan Color visual novel title and some digital patchislot games that are only available in Japan, no other video games have attempted to tackle The Ring, which sadly means that Terror’s Realm is the best and only adaptation available. The frustrating thing here is that I do like the idea that a video game adaptation of The Ring would turn the infamous videotape into a video game. There are some really clever things that could be done with that premise and a survival horror game could truly tap into the psychological horror aspect of this dilemma where the player is just as concerned about this ticking clock element as the game’s protagonist. A survival horror game based on the Ring series could be great, but The Ring: Terror’s Realm goes completely in the wrong direction and squanders the property. If the team behind Eternal Darkness had taken a swing at this for example, perhaps this could have been really special. As it stands, this remains an interesting survival horror relic because of how much of a misfire it is, but just barely. It also likely killed any chances of a Ju-on/The Grudge video game going into production any time soon (although a Ju-on “Haunted House Simulator” would unfathomably come out for the Wii in 2009).

With how far horror video games and licensed properties have come since the year 2000, maybe The Ring will one day get a proper video game adaptation. Whatever’s made couldn’t be any worse than this. Who knows, maybe a Sadako Yamamura skin for Dead by Daylight’s The Spirit character is in the cards? Or at least Meg Rainman will get added to the list of playable survivors.

Editorials

Seeing Things: Roger Corman and ‘X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes’

When the news of Roger Corman’s passing was announced, the online film community immediately responded with a flood of tributes to a legend. Many began with the multitude of careers he helped launch, the profound influence he had on independent cinema, and even the cameos he made in the films of Corman school “graduates.”

Tending to land further down his list of achievements and influences a bit is his work as a director, which is admittedly a more complicated legacy. Yes, Corman made some bad movies, no one is disputing that, but he also made some great ones. If he was only responsible for making the Poe films from 1960’s The Fall of the House of Usher to 1964’s The Tomb of Ligeia, he would be worthy of praise as a terrific filmmaker. But several more should be added to the list including A Bucket of Blood (1959) and Little Shop of Horrors (1960), which despite very limited resources redefined the horror comedy for a generation. The Intruder (1962) is one of the earliest and most daring films about race relations in America and a legitimate masterwork. The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967) combine experimental and narrative filmmaking in innovative and highly influential ways and also led directly to the making of Easy Rider (1969).

Finally, X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963) is one of the most intelligent, well crafted, and entertaining science fiction films of its own or any era.

Officially titled X, with “The Man with the X-Ray Eyes” only appearing in the promotional materials, the film arose from a need for variety while making the now-iconic Poe Cyle. Corman put it this way in his indispensable autobiography How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime:

“If I had spent the entire first half of the 1960s doing nothing but those Poe films on dimly let gothic interior sets, I might well have ended up as nutty as Roderick Usher. Whether it was a conscious motive or not, I avoided any such possibilities by varying the look and themes of the other films I made during the Poe cycle—The Intruder, for example—and traveling to some out-of-the-way places to shoot them.”

Some of these films, in addition to Corman’s masterpiece The Intruder (1962), included Atlas and Creature from the Haunted Sea in 1961, The Young Racers (1963), The Secret Invasion (1964), and of course X, which was originally brought to him (as was often the case) only as a title from one of his bosses, James H. Nicholson. Corman and writer Ray Russell batted the idea presented in the title around for a couple days before coming to this idea also described in Corman’s book:

“He’s a scientist deliberately trying to develop X-Ray or expanded vision. The X-Ray vision should progress deeper and deeper until at the end there is a mystical, religious experience of seeing to the center of the universe, or the equivalent of God.”

While Corman worked on other projects, Russell and Robert Dillon wrote the script, which has a surprising profundity rarely found in low-budget science fiction films of the era. Like The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) before it and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) after, X grapples with nothing less than humanity’s miniscule place in an endless cosmos. These films also posit that, despite our infinitesimal nature, we still matter.

In some senses, X plays out like an extended episode of The Twilight Zone. Considering Corman’s work with regular contributors to that show Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont during this era, this makes a lot of sense. It begins with establishing the conceit of the film—X-ray vision discovered by a well-meaning research scientist Dr. James Xavier, played by Academy Award Winner Ray Milland. The concept is then developed in ways that are innocuous, fun, or helpful to humanity or himself. As the effect of the eyedrops that expand his vision cumulate, Xavier is able to see into his patients’ bodies and see where surgeries should be performed, for example. He is also able to see through people’s clothes at a late-evening party and eventually cheat at blackjack in Las Vegas. Finally, the film takes its conceit to its extreme, but logical, conclusion—he keeps seeing further and further until he sees an ever-watching eye at the center of the universe—and builds to a shock ending. And like many of the best episodes of The Twilight Zone, X is spiritual, existential, and expansive while remaining grounded in way that speaks to our humanity.

Two sections of the film in particular underscore these qualities. The first begins after Xavier escapes from his medical research facility after being threatened with a malpractice suit. He hides out as a carnival sideshow attraction under the eye of a huckster named Crane, brilliantly played by classic insult comedian Don Rickles in one of his earliest dramatic roles. At first, a blindfolded Xavier reads audience comments off cards, which he can see because of his enhanced vision. Corman regulars Dick Miller and Jonathan Haze appear as hecklers in this scene. He soon leaves the carnival and places himself into further exile, but Crane brings people to him who are infirmed or in pain and seeking diagnosis. Crane then collects their two bucks after Xavier shares his insights. This all acts as a kind of comment on the tent revivalists who hustled the desperate out of their meager earnings with the promise of healing. Now in the modern era, it is still effective as these kinds of charlatans have only changed venues from canvas tents to megachurches and nationwide television.

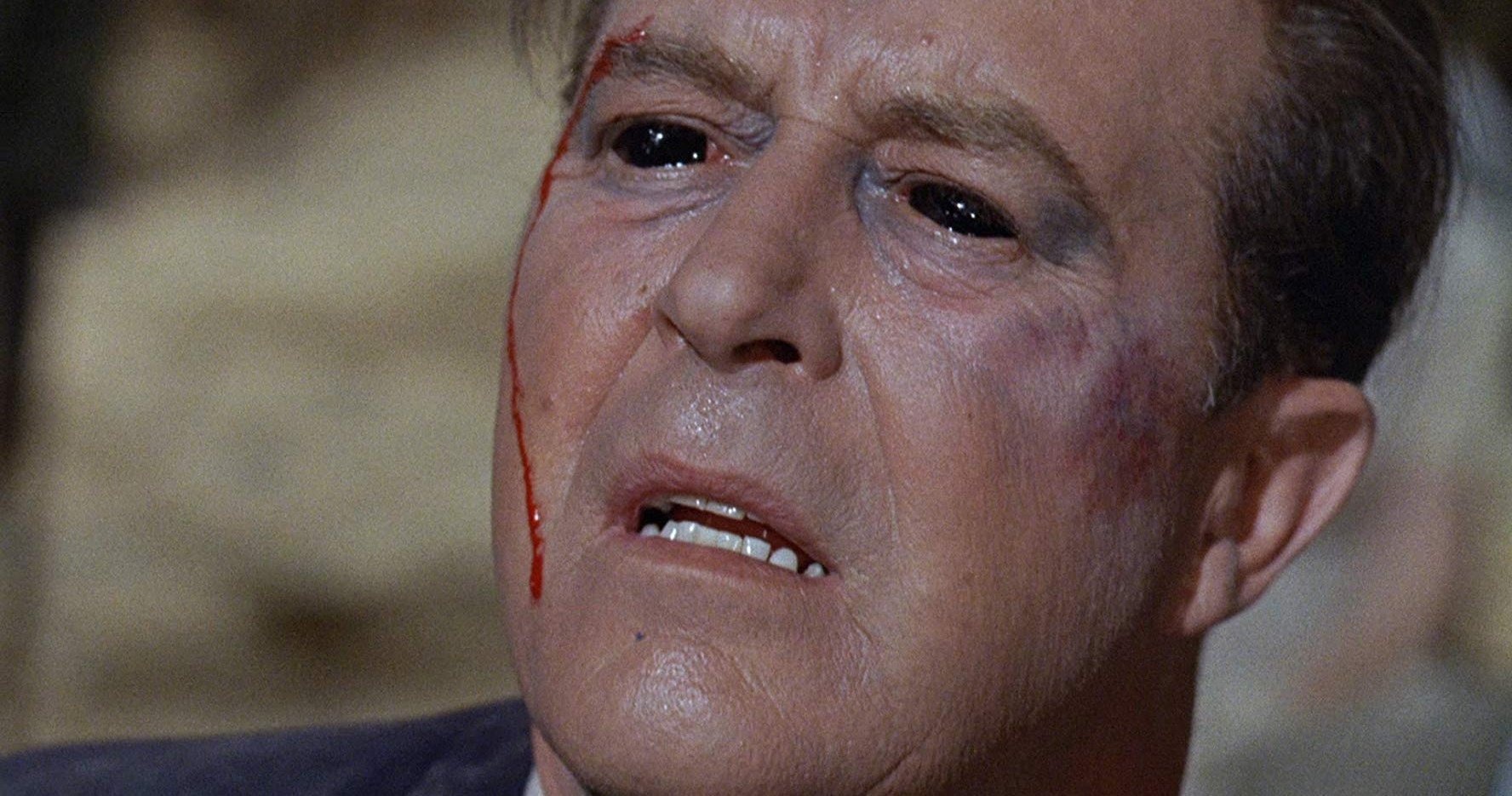

The other sequence comes right at the end. After speeding his way out of Las Vegas under suspicion of cheating at cards, Xavier gets in a car accident and wanders out into the Nevada desert. He finds his way to a tent revival and is asked by the preacher, “do you wish to be saved?” He responds, “No, I’ve come to tell you what I see.” He speaks of seeing great darknesses and lights and an eye at the center of the universe that sees us all. The preacher tells him that he sees “sin and the devil,” and calls for him to literally follow the scripture that says, “if your eye causes you to sin, pluck it out.” Xavier’s hands fly to his face, and the last moment of the film is a freeze frame of his empty, bloody eye sockets.

At this point, Xavier is seeing the unfathomable secrets of the universe. Taken in a spiritual sense, he is the first living human to see the face of God since Adam before being exiled from the Garden of Eden. But neither the scientific community nor the spiritual one can accept him. The scientific community sees him as a pariah, one who has meddled in a kind of witchcraft because he has advanced further and faster than they have been able to. The spiritual leader believes he has seen evil because he cannot fathom a person seeing God when he, a man of God, is unable to do so himself. The one man who can supply answers to the eternal questions about humanity’s place in the universe, questions asked by science and religion alike, is rendered impotent by both simply because they are unable to see. The myopia of both camps is the greater tragedy of X. Xavier himself perhaps finally has relief, but the rest of humanity will continue to live in darkness, a blindness that is not physical but the result of a lack of knowledge that Xavier alone could provide. In other words, he could help them see, or to use religious terminology, give sight to the blind. Rumor has it that a line was cut from the final film in which Xavier, after plucking out his eyes, cries out “I can still see!” A horrifying line to be sure, but it also would have kept the tragedy personal. In the final version, the tragedy is cosmic.

I usually try to keep myself out of the articles in this column, but allow me to break convention if I may. Roger Corman’s death affected me in ways that I did not expect. With his advanced age I knew the news would come down sooner rather than later, but maybe a part of me expected him to outlive us all. Corman’s legacy loomed large, but he never seemed to believe too much of his own press. I’ve heard many stories over the years of his gentle, even retiring demeanor, his ability to have tea and conversation with volunteers at conventions, his reaching out to people he liked and respected when they felt alone in the world. I never had the pleasure of meeting or speaking with him myself, but I did get to speak with his daughter Catherine and sneak in a few questions about her father. It was fascinating to hear about the kind of man he was, the things that interested him, and the community he created in his home and studio.

X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes was the first Corman movie I ever heard of, though I saw it for the first time many years later. When my family first got a VCR back in the mid-80s, my parents quickly learned about my obsession with horror movies, though at the time I was too afraid to actually see most of them. One day while browsing the horror section at the gigantic, pre-Blockbuster video store we had a membership with, my dad said, “Oo! The Man with the X-Ray Eyes! That’s a great one.” For whatever reason, we didn’t pick the video up that day, but I never forgot that title. Then I read about it in Stephen King’s Danse Macabre and, though he spoils the entire movie in that book (which is fine, it’s not really that kind of movie) I was enthralled and became a bit obsessed with seeing it. Of course, by then it was a lot harder to track down the film, so I only had King’s plot description, a few scattered details from my dad’s memory, and my imagination to go by. When I finally did see it, the film did not disappoint. Sure, the special effects, clothes, music, and styles are pretty dated, but the themes and messages of the film are endlessly fascinating and relevant.

It may seem obvious, but X is a film about seeing and all the different meanings of that word. There are those things seen by the physical eye but there is so much more to it than that limited meaning. It asks questions of what we see with imagination, the spiritual, and intellectual eye. It explores what society does to people who can truly see. Some are deified while others are condemned and ostracized. And then there are those questions of if there is something out there that sees us. Is it a force of good or evil or indifference? Is there anything at all out there that looks for us as much as we look for it? It may just be a silly little low-budget science fiction film, but somehow X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes has the power to provoke thought and imagination in a way few films can. It may even have the power to help us see in ways we could only imagine.

In Bride of Frankenstein, Dr. Pretorius, played by the inimitable Ernest Thesiger, raises his glass and proposes a toast to Colin Clive’s Henry Frankenstein—“to a new world of Gods and Monsters.” I invite you to join me in exploring this world, focusing on horror films from the dawn of the Universal Monster movies in 1931 to the collapse of the studio system and the rise of the new Hollywood rebels in the late 1960’s. With this period as our focus, and occasional ventures beyond, we will explore this magnificent world of classic horror. So, I raise my glass to you and invite you to join me in the toast.

You must be logged in to post a comment.