Hands Across the City / Le mani sulla città , Italy 1963

Posted by keith1942 on February 6, 2015

Leeds International Film Festival retrospective of his work in 2005. We saw a 35mm print of this film, made in black and white and in the 1.85:1 ratio. As usual the Italian soundtrack was accompanied by onscreen subtitles in English.

Rosi had worked as an assistant with Luchino Visconti and one can see a strong influence by this director and by the Neo-realist movement more generally on Rosi’s films. At the same time there is a strong individual development in the form and style of his films in this period. The preceding film, Salvatore Giuliano (1961), a study of politics, the mafia and corruption in Sicily in the years at the end of World War II, was an amazing experience back in the early 1960s. It combined a documentary style, with dramatic plotting and labyrinthine plot full of ambiguities. This approach was to be mirrored in later films like The Mattei Affair / Il caso Matei (1972) and Illustrious Corpses / Cadaveri eccellenti (1975). Hands Over the City offers a rather different approach: the ending of the film presents something approaching closure and the resolution of the conflicts chartered through the film are quite apparent.

A study edited by Carlo Testa (1996) proffers the term ‘critical realism’ for Rosi’s films. The approach developed in neo-realism can still clearly be identified, but the use of drama is modified. Rosi’s films have a critical [Marxist] approach in which the distancing [reminiscent of some of the ideas of Brecht] gives a greater emphasis to the political dynamic.

Rosi comes from the city of Naples. And the screenplay was written by Rosi together with his friend and fellow Neapolitan Rafael La Capria together with Enzo Provenzale and Enzo Forcella. The city has provided the focus for several of Rosi’s films and the South is a central issue in his entire output. The South / North divide is a central contradiction in Italian history and has pre-occupied writers and artists, including the in the formidable output of Antonio Gramsci.

The story presented in the film revolves around the political elite in Naples and the question of land. The key character is Eduardo Nottola This was Francesco’s Rosi’s third feature film and one of the films screened in the (Rod Steiger), a property developer but also a council member of the city. The film opens and closes on a development site which Nottola and his associates buy from the city for lucrative developments – ‘today’s gold’ in Nottola’s words. The corruption involved in land dealings becomes a major public issue when construction work in the poor quarter of the city causes the collapse of a Jerry-built block, with injuries and deaths.

Much of the film is taken up with the manipulations and trafficking on the City Council. Here three groups jostle for power – right, centre and left. Apart from Nottola another key character is a leading left councillor De Vita (Carlo Fermariello), presented fairly sympathetically in the film. The other sympathetic councillor is Balsamo (Angelo D’Allessandro), the head of a hospital and member of the centre grouping. Less sympathetic and clearly prepared to endorse corruption and profiteering is Maglione (Guido Alberti), the leader of the right grouping and Professor De Angeli (Salvo Randone) the leader of the centre grouping.

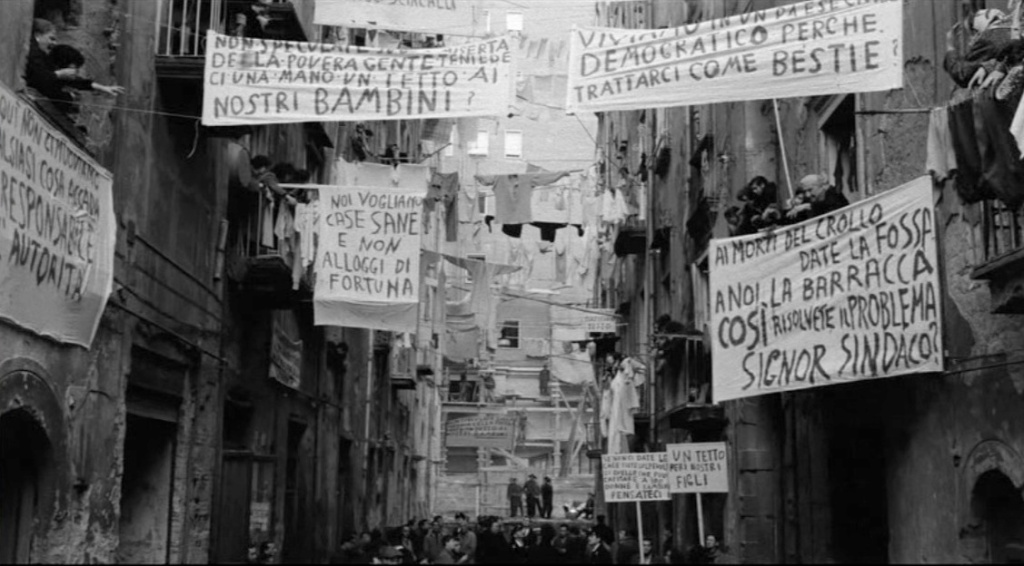

These members of the city’s ruling class dominate the film. The ordinary working people, objects of the exploitation and oppression appear only occasionally. However the film’s treatment of these episodes is powerful. Right near the beginning of the film we see the collapse of the block of flats – the local people both run for cover and then run to attempt to rescue the injured and bring out the dead. We return to this area later when the council announces a plan to clear the area for development under the disguise of health and safety. The narrow street is filed with banners and the jeering populace. A little later the armed carabinieri back up council officials as the working class residents are forcibly moved. And then at the end of the film, in one of the bravura set pieces often found in Rosi’s film, we survey the city streets on the eve of an election. The camera moves around squares and arcades as the different political factions address, even harangue, crowds at hustings.

What is noticeable about the scenes in the working class area is the prominence of women. In the sequence where opposition is voiced to the council plans women dominate the mise en scène. It is they who are in the forefront of agitation whilst the men are much more muted. Rosi’s films tend to focus on worlds dominated by men: in parts a reflection of the social reality of Italy. Strong and central women characters are uncommon, though they do appear, as in his version of Carmen (1984). But they do play a prominent part in the presentation of the working class: notable also in Salvatore Giuliano. Only one woman among the elite receives much attention, Maglione’s lover (Dany Paris). However she is treated rather like a pet and expected to follow him round, and be heard only when he wishes.

The mise en scène in the film is rich in motifs. A recurring scene takes place in Nottola’s high rise offices. One wall is covered in a large-scale map of the city, reflecting his relationship to Naples. One of the later scenes takes place at night and the wide span windows present the darkened city as Nottola paces the room.

The council sequences emphasise the nature of the political traffic in the city. The council chamber is frequently the site of hurly burly argument. But such occasions are constant interrupted as the different groups move to smaller, less public rooms where deals take place. As you might expect from the title ‘hands’ are also a recurring motif.

Rosi’s film relies on a dynamic camera. The cinematographer is Gianni Di Venanzo, who worked on Rosi’s first five films. The film is full of sequence shots and at times the camera dashes towards events, at other times [as in Nottola’s office at night] it prowls round a character. The collapse of the block of flats is a bravura moment in the film. Rosi and Venanzo filmed an actual demolition, using a number of cameras to record the event. The sequence shots in the night of hustings late in the film has a similarly impressive quality.

The music by Piero Piccione is interesting. For much of the time the rhythm and tonal quality is reminiscent of films dealing with criminality. One sequence that accompanied the machinations of the councillors reminded me strongly of the compositions of Bernard Hermann.

The cast presents this world of machinations and cover-ups very effectively. Rosi himself recruited Steiger for the main part. His rather different style make shim stand out in the councillors world. He is a maverick, yet dangerously effective. Other characters like Maglione and De Angeli seem as if taken from the writings of Machiavelli. Carlo Fermariello, playing Da De Vita, was actually a real-life councillor now playing his fictional counterpart. This mixing of the professional and non-professional performers is a recurring constant in Rosi’s films. And he and his production team are able to effectively weave these styles together. So several times we switch from the murky world of the council, predominantly professional performers, to the more dynamic world of the street, predominantly non-professional performers.

Thematically the film deals with the corruption of the political class. One assumes that whilst the film is fictional Italian audiences would easily draw parallels with the actual political events in Naples and in the wider Italy. The film uses the non-de plumes of ‘right’, centre’ and ‘left’, though some reviews identify actual: parties such as the Christian Democrats. This may be clearer in the original Italian than in the English sub-titles. What is clear is that when the film depicts the church it is the dominant Catholic institution in Italy. Religious leaders are not that prominent in the film, but they are always noticeable at points of public endorsement. Thus an opening ceremony for a development includes the blessing by a bishop or archbishop. Interestingly at one point De Angeli proudly shows off his art collection to Balsamo: these include not only two religious paintings but also an actual altarpiece installed in a side-room.

The film was successful in Italy, though reviews often took contrary positions. The article by Manuela Gieri (Hands Over the City: cinema as political indictment and social commitment: also 1996) quotes two examples:

Gian Luigi Rondi in the daily Il Tempo:

No, no no. Don’t come and tell me this is how one should make movies. This is neither cinema nor healthy polemic; it is a political speech, an electoral harangue ….

Whilst Ugo Casiraghi in L`Unita:

A wonderful film, Rosi has authored his most mature work. … It is a film essay with the clarity of a limpid and documented social study.

Of course, the responses are more to do with the political; values of the reviewers than their review of filmic qualities. But in a way that speaks to the effectiveness of the film: its project is clearly delivered. The film won The Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival that year. Like all of Rosi’s films it successfully straddles the popular and the art film – It is engrossing and at times exciting whilst also providing the viewer with stimulation and challenges.

Poet of Civic Courage The Films of Francisco Rosi, edited by Carlo Testa, Flicks Books 1996.

Leave a comment