“Who is right, who can tell, and who gives a damn right now”

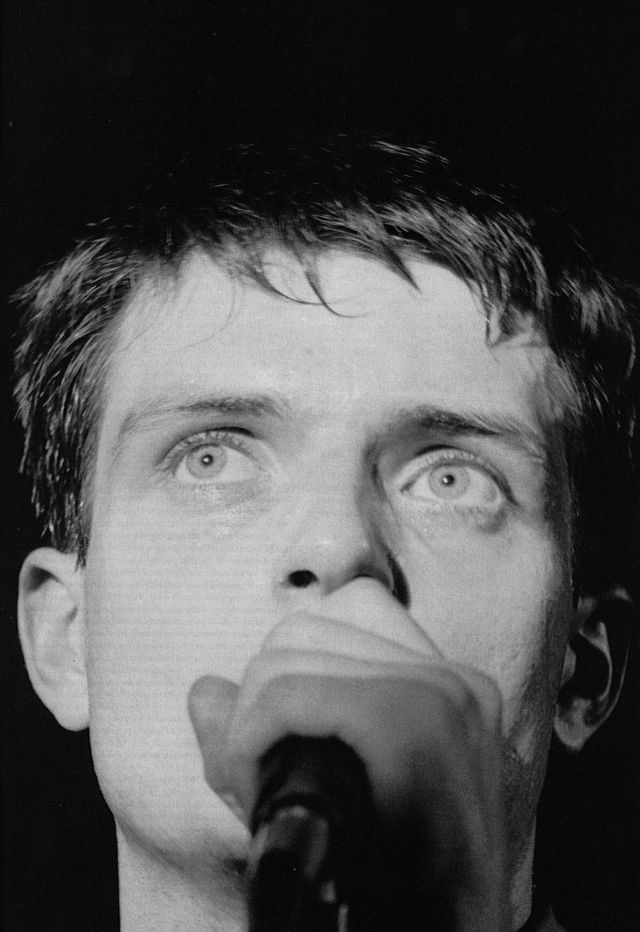

This is a case study of the continuities between living, performing and writing. When Ian Curtis hanged himself at the age of 23, tortured by epilepsy, medication, fear and remorse; having just started a promising career as singer and songwriter for the band Joy Division, after releasing two intriguing long plays and a hit single called “Love Will Tear Us Apart”, and about to embark on their first American tour, he was staging his ultimate performance. The act turned him into a cult figure, as it gave an eerie resonance to the increasingly gloomy lyrics he had written for his band.

Music journalists began to write about Joy Division in a more vivid, dramatic way. People who had never seen the band perform live, or even heard of them while Curtis was alive, became fans. Joy Division was hailed in their native Manchester, England, as youthful symbols of the postmodern city, and in the rest of the world as founders of the gothic rock scene. They were subsequently the subject of biographies, biopics and documentaries which focused particularly on Curtis’s personality, and the main webpage devoted to the band (joydivisioncentral.com) lists about twenty Joy Division tribute bands performing their songs, while Youtube enables fans and critics to watch the band perform at several gigs on very low quality footage, and much more visually appealing clips of actor Sam Riley performing as Ian Curtis in the biopic about him, Control (2007). At present the hyperreal Curtis of Control seems to be on the verge of replacing the real one, since video and image searches are often directed to Riley’s role-playing rather than to Curtis himself. I was probably not alone in returning to Joy Division and Ian Curtis with a renewed enthusiasm after watching the movie.

As I will never have the chance to see Joy Division perform live, I will have to be content with re/viewing other people’s writings on a band “who capture the imagination and make history with an incandescent performance that would be studied for years” (Morley 17). However, as Phelan reminds us, “performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance […]. The document of a performance is only a spur to memory, an encouragement of memory to become present”; in other words: it becomes history, and, by that token, narrative writing. I will therefore dwell on the descriptions of Joy Division’s performance by others, particularly those who met the band and attended their live performances. My interest is archeological: it is history of, but also as, performance. No attempt will be made to reconstruct a lineal history, however, or to disguise my modest experience as a fan. I adopt a collage approach to performance studies (Kilgard) in order to restate the multifaceted complexity of the Joy Division myth in a kaleidoscopic form, rather like the tracks in a conceptual album which need not be read in sequential form, except perhaps for the present opening section and the concluding one.

Writing Joy Division: David Morley’s performative approach to history writing

I will not argue the matter: Time wastes too fast: every letter I trace tells me with what rapidity Life follows my pen. (Sterne)

I was among the many who discovered Joy Division’s music too late, when the band no longer existed. I probably heard “Love Will Tear Us Apart” on the radio in later 1980 or ‘81. Then I went to my local record shop, saw the mysterious funereal cover of their second album, Closer, and asked the shop assistant to play it for me on one of the turntables they had for customers. It is hardly possible to recall over thirty years later why I liked their music, but I believe I can retrieve much of the feeling by reading one of Paul Morley’s later descriptions of it. In the opening section of his Nothing (2000), “a northern memoir concerning Stockport, the self and suicide,” Morley imagines Ian Curtis’ dead body miming to the words, “This is the way, step inside,” from “Atrocity Exhibition,” the first track on Closer:

Drums would be pummeled with detached precision, bass guitar would ramble up from deep out of the ground and a guitar, as if it were an electronically charged knife, would cut through the atmosphere (…). The voice the body was miming would croon with a kind of objectless longing, an urgent aimlessness. (Morley)

The problem of representing performance that Morley is facing here resembles Hazel Smith and Roger Dean’s descriptions of their work in the electronic ensemble austraLYSIS in “Live Music; Dead Bodies” (2012). Smith and Dean also imagine a dead musician performing, as well as staging an ironic protest against “the genetic manipulations, transplants, abortions and acts of voluntary euthanasia that are regularly carried out on music and austraLYSIS’s performances.” Similarly, Morley seems to be wondering whether performance can ever be brought to life, except as variously manipulated fiction.

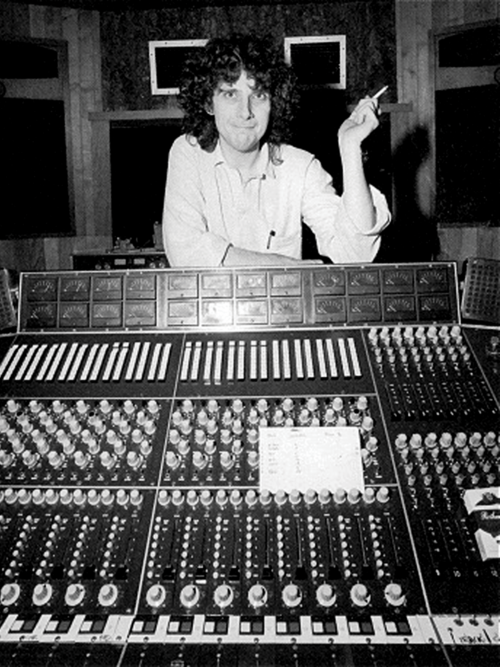

If Morley is sometimes considered the writer who best accounts for the art of Joy Division, it is not just because he was relatively close to them at some of their turning points, but also thanks to the performative character he has been trying to imbue his writing with through the years, exhibiting what Phelan calls, “The open hand writing; the emptiness of the word carving a space for others to inhabit”. In Joy Division Piece by Piece: Writing about Joy Division 1977-2007 (2008), Morley emphasizes a sense of writing performance in three ways: by bringing together different pieces of writing (in chronological order, but interspersed with recent introductions and commentaries, and some of them not dealing with Joy Division, but with groups considered within their entourage, such as Buzzcocks or Cabaret Voltaire) in the manner of a collage rather than a unitary compilation; by insisting on history as something provisional, present, and future-oriented, as it seems to him, “it’s more appropriate not to create a settled version of events but to keep the versions of events always moving, and therefore part of the current world, not part of a disappearing world”; and, finally, by always revealing a personal bias in his narrative, for example when he repeatedly relates his experience of Joy Division to the suicide of his own father at the age of 40 in 1977, the year when Morley also saw the first concerts by Warsaw, the band who would soon rename itself Joy Division. Morley’s biography of the band and his history of their Northern England scene are purposefully impinged upon by his autobiography and his claim to being their chronicler: after all, he was learning to write about rock music professionally as Joy Division was learning to play. He thus suggests how the personal element is paramount in anyone’s exposition to music as performance. He is also acutely aware of the difficulty of writing anything final about Joy Division—of turning performance, or a life, into a book.

Controlling stories

According to legend, it was Tony Wilson, a TV broadcaster who owned Joy Division’s label Factory Records, who took Morley to see Ian Curtis’ corpse, because he needed that experience to write “the book” about the band (Curtis, Middles and Reade).

In fact, the task to write the primary Joy Division biography was taken up by the singer’s widow, Deborah Curtis, whose daughter Natalie was just a year old when her father left them. She wrote the book partly to take control of the story of Ian Curtis from Tony Wilson and the music world in general, which she largely blames for her husband’s death (Curtis). It is most unusual for a rock star’s wife to be the one to narrate his authoritative biography. The reputed music critic Jon Savage, in his preface to Touching from a Distance, mentions “something that is ever present but rarely discussed, the role of women in the male, often macho, world of rock” (Curtis xiii). Savage then cites a key scene in the book which is duly represented in the film Control, when she was pregnant and the organizers of a gig objected to her presence at the venue: as she wryly commented on it, “from the point of view of managing a band, it made sense to keep their respective women away. (…) If Ian was going to play the tortured soul on stage, it would be easier without the watchful eye of the woman who washed his underpants” (Curtis). Thus Touching from a Distance succeeds in demystifying Ian Curtis and turning the tables on the myth that the author believes to have killed her husband. There is also a sense of reckoning at work: the chance to pay back the partner who betrayed her, taking historical control over the dead body. The book offers an essential experience of Joy Division’s mind and intellect, even if one may also get an uncanny feeling of puppetry and ventriloquism about it, as when Morley imagines Curtis’ dead body crooning to the music of Joy Division. The same ventriloquism can be felt whenever we use, as she does in her book, the titles or lines of his songs as headings of chapters interpreting his life.

A further act in this struggle for control of Curtis and Joy Division’s story is the alternative biography that Wilson’s ex-wife Lindsay Reade would co-write with the music journalist Mick Middles, Torn Apart: The Life of Ian Curtis (2006), where, with no thanks to Deborah, they clearly adopt the perspective of Tony Wilson, Ian’s sister and parents, and his mistress, Annik Honoré, a refined Belgian groupie. Annik is allowed to absolve herself from accusations that she reacted insensitively to Curtis’ epileptic fits by declaring that, precisely when he suffered them, she “loved him more than ever because he was utterly lost” and that on those occasions he actually looked “supernatural,” as he was “kind of glowing and was literally rising from the ground” with the convulsions (Middles and Reade). Such intimations of mysticism are confirmed by suggestions of his clairvoyance, Annik’s virginity throughout her relationship with Ian (they always refrained from intercourse and “slept together like two kids”, the way his body was found after the rope had stretched and “he was knelt on the floor as though he was praying”, and Annik’s dream of a strong light through which Ian was telling her “he had managed to find peace now”

.

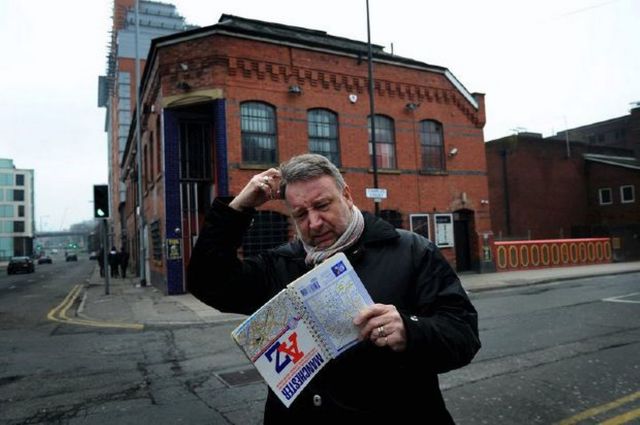

Besides the memoir and the cult biography, another way of recreating Joy Division’s story in writing is by integrating it within the history of popular culture, art and life in Manchester since the late 1970s. This is what Michael Winterbottom’s film 24Hour Party People and Tony Wilson’s novelization of the screenplay, 24 Hour PartyPeople: What the Sleeve Notes Never Tell You, do. In every book on Joy Division, to some extent, the band and its fated genius represent metonymically the Mancunian environment in which the band members grew up and Curtis ultimately died. Ott, for instance, argues that “the sense of despair and frustration that Curtis’s lyrics conveyed had broad implications in the England of the late 1970s, where hopelessness was a very real sensation,” and Manchester in particular “was in state of economic stasis”. Today’s “romantics” like to imagine that Joy Division played “Manchester music emerging from the grimy residue of its lost industrial heritage” (Middles & Reade). This historical focus is more accurately developed in Grant Gee’s documentary Joy Division (2007), written by the music journalist Jon Savage. It makes a point of adding the social realism which was found largely missing from other accounts, such as the film Control, where “It’s hard to guess from its beautifully silvery photography that it is set in the 1970s, a period of strikes and conflict and de-industrialisation, when Manchester was grimy and deserted” (Sandhu). In the initial images of the documentary we hear the narrator’s voice (Jon Savage) over a nocturnal view of Manchester city: “I don’t see this as the story of a pop group, I see this as the story of a city that once upon a time was shiny and bold and revolutionary.” Then, over images of kids playing in derelict 1970s streets, Tony Wilson’s voice tells us “it felt like a piece of history which had been spat out—this had been the historic centre of the modern world. We invented the industrial revolution in this town …” Images of the industrial revolution and a young working girl from the 19th century fade into that of a 1970s girl playing around ruined council flats, and other images of kids playing in desolate streets, an abandoned car, demolished housing estates, and a horsed-policeman, leading to the surviving members of Joy Division relating their experience growing up in such settings. Thus the documentary responds to Tony Wilson’s ambition to give the Joy Division experience a transcendental sense as embodying the drama of postmodernity in Northwest England.

Writing performance: the absent subject

Without a copy, live performance plunges into visibility – in a maniacally charged present – and disappears into memory, into the realm of invisibility and the unconscious where it eludes regulation and control. (Phelan)

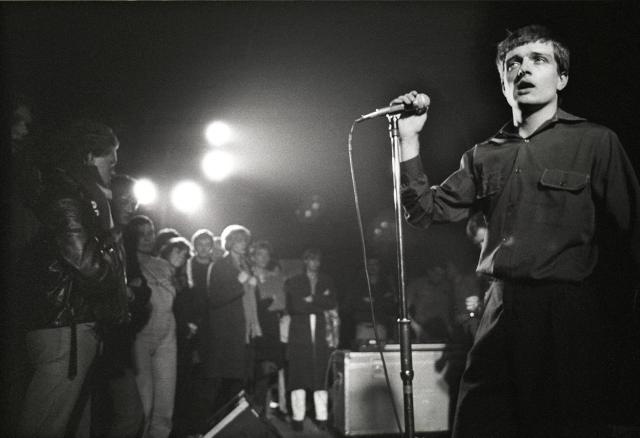

The history of Joy Division’s performance always begins with the legendary Sex Pistols gigs at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester, June 4 and July 20, 1976, which were hailed as “the Emotional Revolution” that would push the 19th-century city of the Industrial Revolution into the 21st century (Morley). Commenting on the “problematic reconstruction” of the June 4 gig in the film 24 Hour Party People, and on more accurate attempts to recall the performance of the Sex Pistols there (Nolan), Albiez argues that, besides the people who saw the Sex Pistols on those occasions and how they were inspired by them, their cultural impact had to do with a combination of factors including the press coverage of the events in Sounds, New Musical Express and Melody Maker, and the Sex Pistols’ appearance on Granada TV’s So It Goes, among others. These same music papers and TV program would be decisive for Joy Division’s initial popularity.

The Sex Pistols alone, however, would not suffice to explain Joy Division’s outlook on performance. It is crucial to take account, as Middles and Reade do, of the fascination held since the early 1970s by “those performers who were pushing at the boundaries,” especially David Bowie, and Iggy Pop, “another right performer at exactly the right time” for Curtis to learn from. Bowie offered a model for drama and creative personal transformation, while Pop would chiefly stand for sheer intensity, as well as a certain feeling for stage self-immolation: “In witnessing the performance [of Iggy Pop on March 3, 1977, in Manchester Apollo], Ian Curtis had taken a step closer to realizing his own dream” (Middles and Reade). The last record Curtis heard before dying was Pop’s The Idiot, which was made in close collaboration with Bowie. Thus it is important to stress that Curtis’ style of performance, far from depending only on his solipsistic genius, resulted from his attendance to other rock artists’ performances, and is therefore embedded in a history of performance.

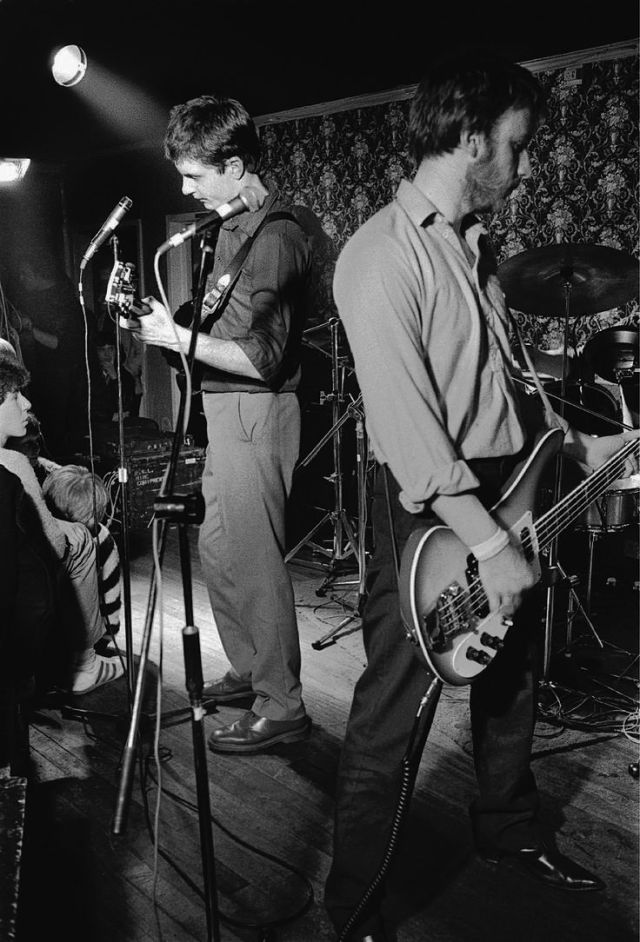

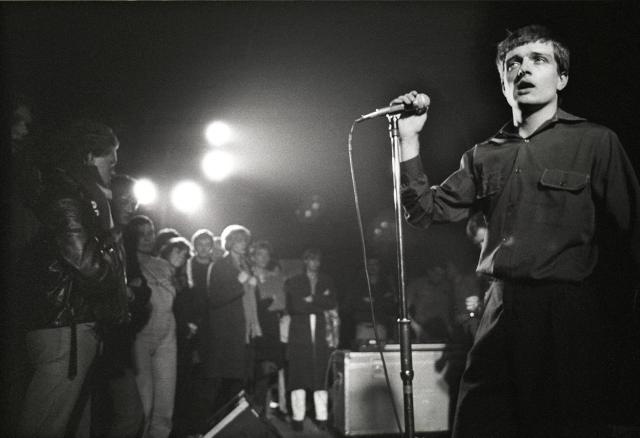

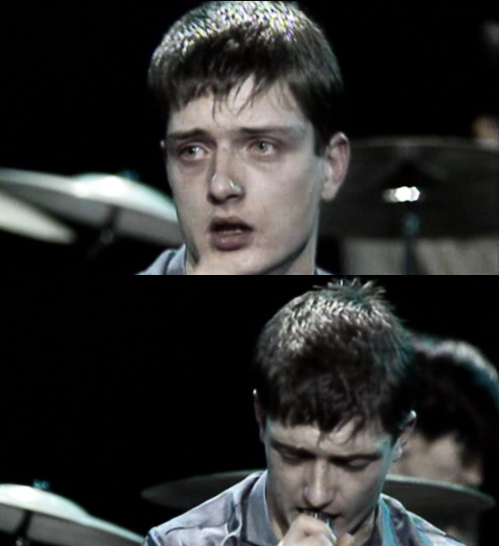

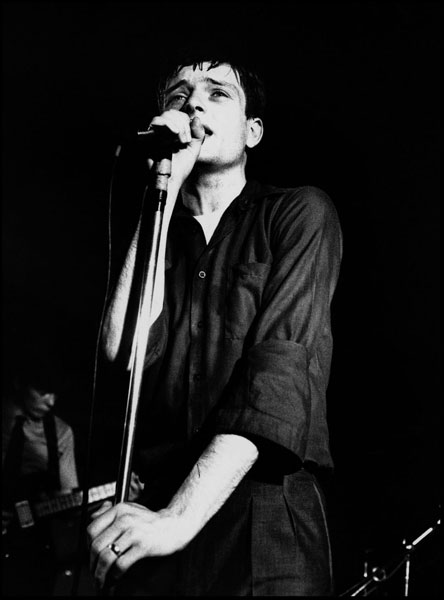

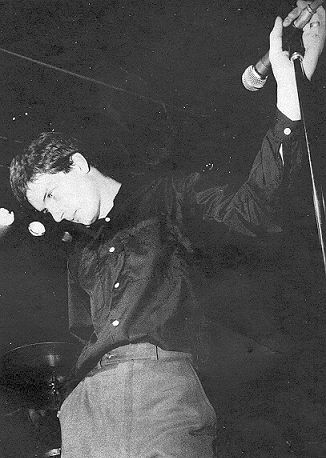

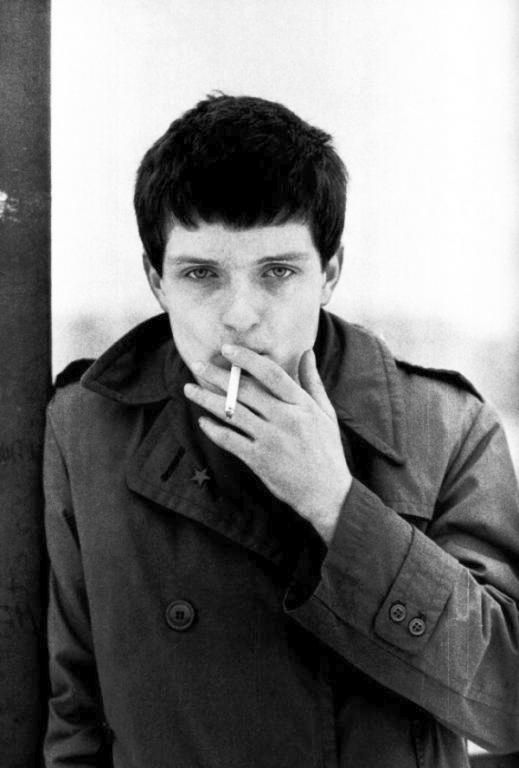

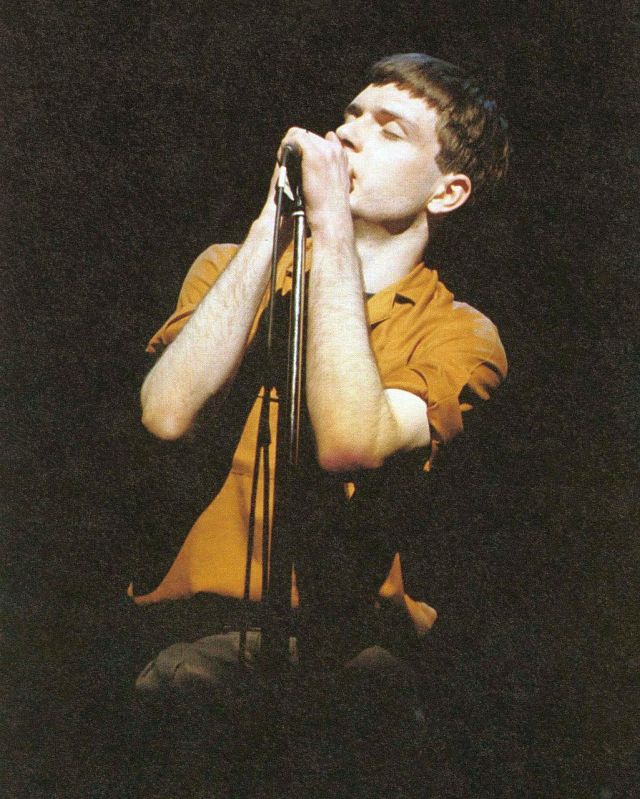

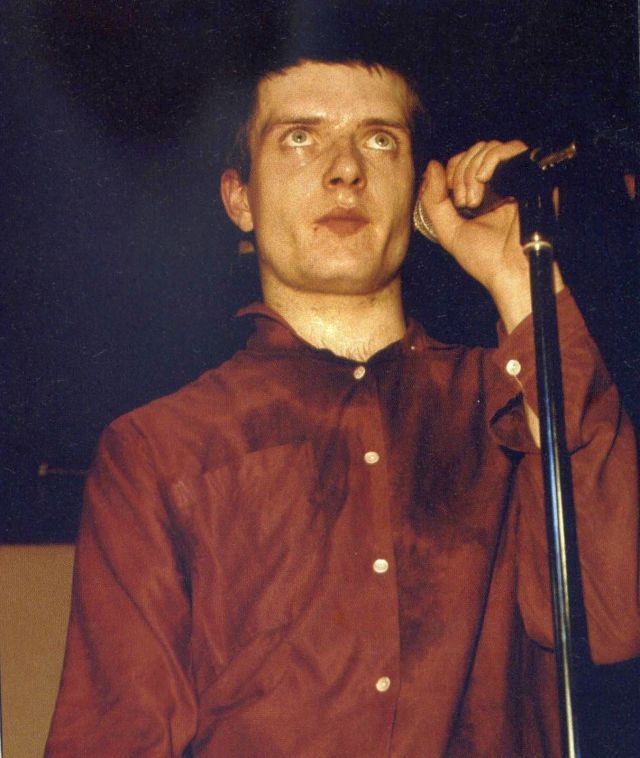

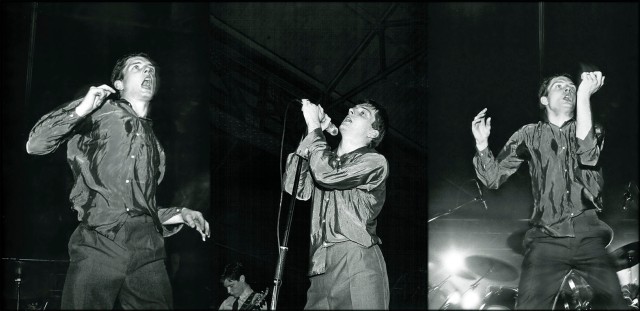

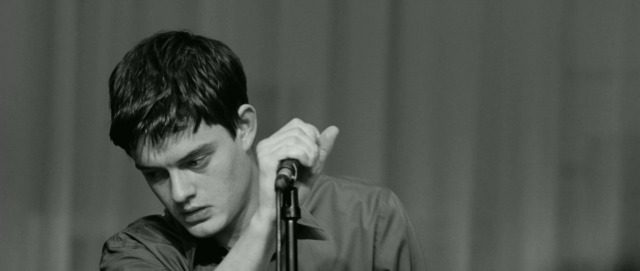

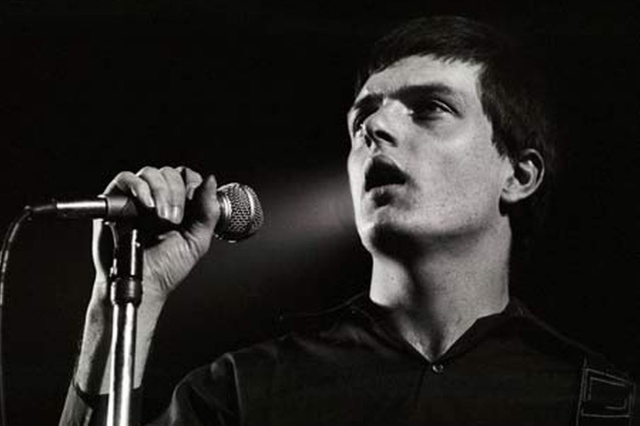

Joy Division’s special contribution to the history of performance is often defined as the rare intensity of Curtis’ creation. Analyses of his performance highlight its “frightening” intensity (Morley). Thus Savage prefaces Deborah Curtis’ book by stating that it was “a performance so intense you’d have to leave the hall,” as Curtis shed the performer’s “necessary psychic self-possession” and “surrendered himself to his visions” entirely on stage (xii). Deborah Curtis, generally focusing on the closeness between his performance and his suicide, portrays him as “a performer from a very early age” who “seemed to be forever taking his fantasies to the extreme”. For Wilson, Joy Division members were not limited to rock star posing, they were “artists who ‘meant’ it. More than meant it. Had no choice” (2002). They would take their performance to the last extreme and beyond that. Various metaphors have been used to describe the way Curtis danced. At the time it was commonly referred to in the music press as the “dead fly dance” (Ott).

More dramatically, Morley has referred to it as “trapped butterfly flapping” (Morley). In a July 1979 issue of Melody Maker Jon Savage explained how “Live, he appears possessed by demons, dancing spasmodically and with lightning speed, unwinding and winding as the rigid metal music folds and unfolds over him”; in the same month Mick Middles wrote in Sounds how Curtis “often loses control. He’ll suddenly jerk sideways, and, head in hands, he’ll transform into a twitching, epileptic-type mass of flesh and bone” (Ott). Ott distinguishes two systemic patterns of dance in Curtis’ performance:

In the more famous, his right arm crosses his hips as the left swirls in an arc past his face: this movement gives the impression of a man swimming desperately for shore, trying to get the leading edge of time itself behind him. The second pattern is more disturbing to behold, a less-ordered flailing at the elbows, like a child swatting a swarm of mosquitoes”.

Ott adds that these movements indicate “pre-seizure activity,” and so does a third one, in which “as Ian’s head darts from side to side, like a spinning top, you can see his eyes are staring straight ahead, locked onto some object that kept him rooted in the moment” (Ott). For Morley, in sum, focusing particularly on the movement of his feet running on the spot (Morley), “He danced with controlled uncontrollability as if he wanted to outstrip the speed of the planet. His epileptic fits sickly emphasized his need to move faster than the world” (Morley). All these images touch on the singer’s urge to dance faster than the band’s music tempo, to go beyond, as it were anticipating his tragic departure from his mates, and the continuity between his performance and his epileptic condition.

Performing sublime: ritual as violent spectacle and the failure of speech acts

The title of the first song on Closer, “Atrocity Exhibition,” comes from a book by J.G. Ballard about a character called Dr. Nathan, in whose mind “World War III represents the final self-destruction and imbalance of an asymmetric world, the last suicidal spasm of the dextro-rotatory helix, DNA. The human organism is an atrocity exhibition at which he is an unwilling spectator”. Curtis’ song lyrics, in turn, begin with an image of “Asylums with doors open wide / Where people had paid to see inside, / For entertainment they watch his body twist, / Behind his eyes he says ‘I still exist’…” For those who knew about his epileptic fits on stage, the allusion to watching “his body twist” would be unmistakable. In this light may also be interpreted the gladiatorial imagery in the song’s next stanza after the obsessively repeated refrain, “This is the way, step inside”: “In arenas he kills for a prize, / Wins a minute to add to his life. / But the sickness is drowned by cries for more, / Pray to God, make it quick, watch him fall” (Curtis). Although the song’s imagery later adds apocalyptic “mass murder” and “dead wood from jungles and cities on fire,” the burden of interpretation tends to remain with the singer offering his fight on stage, the gradual destruction of his body by a twisting sickness, for a paying audience. Some of his dancing movements actually resembled a fight against an invisible enemy, which was perhaps his physical and moral decline.

The meaning of “Atrocity Exhibition,” and of the artist’s stage image as a whole, can also be compared to the spectacle of the French performance artist Orlan, who, since 1990 was having cosmetic surgeries and videotaping them for art exhibitions. Although Orlan’s aim may be to “challenge the patriarchal imperative to control the body” (Faber), a political aim Curtis was not concerned with, the overall aesthetic effect of both artists’ performances concur with the meditations of the philosopher Georges Bataille upon the bodies of torture victims: “like Bataille, Orlan enacts the transformation of self into a sacred figure and art. Her art dissolves distinctions between subject and object, author and work” (Faber). Curtis realized that his body, especially because of the close connection between his dance and his epilepsy, between his lyrics and his life, had become a public site of performance, and the object of a ritual that could lead up to immolation. The criticism implicit in Curtis’ performance is against the terrible demands of the rock culture on the devoted artist.

We are not usually supposed to take song lyrics literally. Not even those closest to Curtis really believed his performance of suffering was something he was living through, both offstage an on. His drama did not just represent, it actually presented what was happening. The “unknown pleasures” of Joy Division were, as in Lyotard’s definition of the postmodern sublime, the pleasure and pain of presenting the unpresentable (Counsell and Wolf). They would finally believe him when he overdid his stage performance, fatally lost control, and killed himself. However, in doing so he was also losing control of his meaning, as the various contradictory accounts of his life and end suggest. Like the woman having an epileptic fit in Joy Division’s “She’s Lost Control,” Curtis “gave away all the secrets of [his] past.” His act bespeaks the failure that pervades speech act and every performance (Phelan). For suicide must be an unhappy speech act according to J.L. Austin’s (1975) notion of performative utterance, provided suicide is regarded as an action that makes a very messy, controversial statement.

Living myth: performativity, intertextuality and suicide of rock stars

Arguably no other “rock ‘n’ roll suicide” was accomplished so dramatically and meaningfully. From his first attempt (as narrated by Ott) Curtis seemed to be planning his suicide as a performance responding to the ideas he found in songs by David Bowie like “All the Young Dudes” and “Rock’ n ’Roll Suicide.” There seems to be a deliberate intertextuality, or hidden suicide note, between his death and the lyrics of Iggy Pop’s “Tiny girls” in the record which was found spinning on his turntable, which speaks about not wanting to live because of bitter disappointment with girls (the last person he spoke to was his wife, who was determined to proceed with their divorce), and the last film he watched, Werner Herzog’s Stroszek, whose hero, a musician, shoots himself after travelling hopefully to America only to be betrayed by his girlfriend and by an economic system which is symbolized in the final scene by some chickens that are made to play and dance obsessively inside a slot machine. He seemed to be acting on a script, whether by Pop and Bowie; by Herzog; by Jon Savage, in his review of Unknown Pleasures where mentions taking rope in the house of a hanged man (Savage); or by the no less premonitory funereal sleeves of Closer and Love Will Tear Us Apart. Furthermore, he was improving on the “heroic” deaths of other rock stars like Jim Morrison, which look more accidental. Curtis seemed to act on the idealized lines of songs calling for a youthful death, rather than imitating actual rock and roll suicides.

These are some of the many traces he left behind for interpretation. Ultimately, whether Curtis’ suicide was planned or accidental, and how far it was inspired by the music he heard or the films he watched, are highly speculative matters. It was a solitary, deeply personal act. Even those who met him personally and write about him with a degree of knowledge, like Deborah Curtis, Morley, Wilson, Annik, or Middles and Reade, can only claim a fragmentary understanding of his motivations, which therefore remain overdetermined. For those of us who never met him or even saw him play live, he is very much a historical, almost fictional, character who lived in a distant epoch, and we can only approach him in a profoundly mediated way, through the writings of witnesses to his life and performance.

Morley’s mission with regard to Joy Division, and, for that matter, that of every fan, critic or biographer of a band’s performance, may be fruitfully compared to what the photographer Sophie Calle did in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, after several paintings were stolen in 1990. Calle asked visitors and museum staff to describe the stolen paintings, transcribed these texts, and placed them next to her photographs of the galleries, suggesting “that the descriptions and memories of the paintings constitute their continuing ‘presence’, despite the absence of the paintings themselves” (Phelan). As Phelan points out analyzing Calle’s performative art from a Lacanian perspective, “The description itself does not reproduce the object, it rather helps us to restage and restate the effort to remember what is lost (…). The disappearance of the object is fundamental to performance; it rehearses and repeats the disappearance of the subject who longs always to be remembered” (Phelan). Writers like Morley cannot really aim to achieve full control of Joy Division’s story; they just keep encouraging others to listen to the band, write about it, and “perform” it to themselves and others, much like Sam Riley interpreting Ian Curtis in Corbijn’s film, because they think it has a present and future historic relevance as an enduring myth.

“Insight”: My Unknown Pleasures sweatshirt

I believe we should be wary of passing judgment on Curtis’ act, for instance, by comparing Curtis to “Goethe’s infamous creation, Werther” (Ott 94). The only fairminded approach to his case is probably a subjective one. Therefore I should state my position as a fan. I probably never heard of Joy Division until the band had disappeared. At the time Joy Division was playing, my favorite rock group was Genesis. Annik did not want Joy Division to adopt the pretentious sound of progressive rock that punk reacted against (Morley).

When I became a fan of Joy Division, I was also listening to post-punk bands like The Durutti Column, The Cure, Bauhaus, The Church, and Throbbing Gristle. I still enjoyed the music of the former generation (e.g., Supertramp, Genesis, Pink Floyd, and Yes), along with more “pop” post-punk music like The Smiths, Ultravox, Talking Heads, and (of course) New Order, in addition to many Spanish groups, some of which, particularly Décima Víctima, showed a remarkable Joy Division influence. In the 1980s I became infatuated with “gothic rock” aesthetics and moods, which I complemented with readings of Sartre, Camus, Samuel Beckett or John Fowles. I see myself in a faded picture rowing in the Lake District in the autumn of 1985, aged 23, wearing a sweatshirt with the famous Unknown Pleasures pattern. Life is but a dream. I assumed E.M. Cioram’s dictum, “The man who has never imagined his own annihilation, who has not anticipated recourse to the rope, the bullet, poison, or the sea, is a degraded gallery slave or a worm crawling up the cosmic carrion.” To me, Ian Curtis was a presence like the dreams that keep calling him in “Dead Souls” (though I always imagined I would die listening to Yes’ “Close to the Edge”). I was under his spell until, around 1990, my wife—my own controlling “Debbie Curtis”—told me to get that bloody suicide nonsense out of my head. I survived Joy Division.

Breaking “Glass”: uncontrollable metaphors

Accounts of Curtis’s life tend to be dominated by certain controlling metaphors, conforming a discourse on Joy Division which draws on the lyrics and is often based on binaries like outside/inside (as in the design of Unknown Pleasures, in the chorus of “Atrocity Exhibition,” and in the title of Peter Hook’s memoir); distance (as the title of his biography, Touching from a Distance, a line from “Transmission”); closeness (as in the album Closer); or control and its loss. Glass-breaking imagery is by no means less revealing. Yet its meaning in Joy Division’s songs is purely figural, and its contrived obscurity bears comparison to the connection between title and lyrics in Bowie’s song “Breaking Glass” from Low (1977), a favorite of Curtis’, the meaning of which is notoriously difficult in terms of symbolic connotations.

The biographies of Ian Curtis relate various glass incidents in the singer’s life. His wife illustrates his self-directed violence narrating incidents when he broke a glass door during an argument with her, smashed glasses, or was so manic on stage he didn’t mind rolling around a broken glass (Curtis). We may catch glimpses of possible symbolic significances of glass in the singer’s career, culminating at the concert in Bury that “turns into a riot, as if to symbolize to Curtis a world that was disintegrating, a life that was over” (Morley). The riot resulted from an attempt to replace Curtis, because of his severely declining health, with another singer. It started when someone in the audience threw a bottle at a beautiful crystal chandelier hanging above the stage. Those on stage “got completely showered with shards of glass and bits of chandelier” (Middles and Reade). The way this moment is represented in the various accounts of Curtis’s career bears comparison to the episode in Brian Gibson’s film Breaking Glass (1980), when a punk singer played by Hazel O’Connor sees a young man die from a stabbing in front of her stage, in the middle of a riot which a concert of her band, precisely called “Breaking Glass,” had provoked. She falls into a deep depression that makes her lose control of her career, an opportunity which her record company seizes to manipulate her at their will. Unlike the fictional singer in that film, however, Curtis had no loving manager to save him in the last resort. Blaming himself for the disaster at Bury and “Weeping uncontrollably (…) [, Curtis] in all likelihood crossed a boundary on the night of April 8th from which he never returned” (Ott). This was really when performance lost control. He died 40 days later, on May 18th. The lyrics he had been writing for Closer and “Love Will Tear Us Apart” have been read as his suicide note (Reynolds), in spite of the deliberate ambivalence pop song words may often have.

Since glass seems to have acquired a peculiar symbolism in relation to Joy Division, from the glass-breaking effects in “I Remember Nothing” (the last song in Unknown Pleasures, 1979) to New Order’s “Crystal,” it is worthwhile considering its presence in the lyrics of two other Joy Division songs, one of which was written quite early in the band’s brief existence, and the other late: “Glass” (1978) and “Something Must Break” (1980). While some of the song titles are explicitly repeated in the lyrics and often form the chorus, in “Glass” the connection between title and lyrics can only be inferred. Likewise, in “Something Must Break” the title phrase is used twice in the last stanza, but its relation to previous lines can only be guessed at: those lines are, “If I can’t break out now, the time just won’t come” (one of his characteristic hopeless statements), “Looked in the mirror, saw I was wrong,” and “I see your face still in the window,” the latter being the first line in the final stanza, which repeats “Something must break (now)” in the third and last lines, suggesting that what breaks may be the window, probably also the mirror.

The play of association and free inference is also the one at work in Touching from a Distance and other biographies of the band which use titles from the songs as chapter titles, inviting readers to find symbolic connections between the narrative in the chapter and the songs, even though, as Morley knows too well, Curtis’ words “omit links and open up new perspectives: they are set deep in unfenced, untamed darkness” (Morley). Indeed Wilson states, “It’s disgusting the way some people quote Joy Division lyrics to explain Joy Division things,” to which he cynically adds that he will be no exception to this in his narrative version of the movie 24 Hour Party People, since “novelization is an intrinsically disgusting art form”. On the other hand, Wilson also justifies such interpretations when, in the same book, he quotes “Aneek” (his spelling for Annik Honoré) saying about Ian shortly before his death, “He means these things, they’re not just lyrics, they’re not just songs, he means it”. In short, Ian Curtis, by writing about suicide and then carrying it out, seems to be inviting a joint reading of his songs and life. His lyrics, like Momus’s glass in Tristram Shandy, invite us to see through his heart and look inside his soul. But such glass is prone to break, and we discover nothing behind, because it is a mirror glass, like the crystals the Lover finds at the bottom of Narcissus’ well in the medieval Romance of the Rose. Like Derrida’s Glas (1974), Curtis’ lyrics tend to erase their meaning and become pure textual performance and sound. His glass imagery is another instance of symbolic games of signification losing control.

“I saw all knowledge destroyed”: representing performance in history

In the end, all I can do, is read the biographer’s paragraph on the subject’s dead body and make an imaginative stab at the penumbra of his words. (Byatt)

In the preceding pages we have discussed the complex relation between performance and re/presentation. We may conclude by classifying various perspectives on the analysis of performance culture (see Bell), all of which are mentioned in the biographies of the band but would require further examination beyond the scope of the present article: the artist’s subjective views of his identity as performer, as well as the viewpoints and contexts of those writing about the artist—all that counted on him, but it was probably the medication that made him lose control and perform his actual death (Reilly in Middles & Reade); the institutional, material aspects of work for a rock band and the rise of Factory Records, which gave the band great creative freedom but also put pressure on Curtis, their greatest star (Middles and Reade; Morley); the problem of the music industry seizing control of an artist’s identity, as dramatized in Gibson’s contemporary film Breaking Glass; the structural: as Wilson stated (cited in Curtis), “it’s always the problem in this industry – having a home life as well,” when the artist falls under the company’s control (Middles and Reade); the dramaturgical, including his innate love of drama (Curtis; Middles and Reade), his dramatic response to the rituals and conventions of music performance and life: an early fascination with “those performers … pushing at the boundaries” (Middles and Reade); his focus on “meaning and magic” rather than stardom (Middles and Reade), as well as the fact that there was, in Joy Division’s performance, a strong element of liminality, of ritual crossing of symbolic boundaries (Turner) which ended up affecting the singer’s life offstage. Finally, the critical outlook,which approaches the culture of performance as heterogeneous, dynamic, and contested: we have suggested how writing about performance must be a performative act in itself.

From a generally constructivist point of view with an emphasis on control in the emplotment of history (see Valdés & González), we have focused not on what Ian Curtis’ performance was like, but on what it was made out to be, which means it will always remain open to further historization, or performative history-writing. It is this present and future potential of Joy Division that Morley emphasizes. He knows that even when those like him who knew Ian Curtis are themselves dead, others who never saw them alive will surely continue to hear, watch, read, talk and write Joy Division. They will consecutively attempt to control the meaning of the band’s performance, only to find how final control will inevitably evade them.

© J. Rubén Valdés Miyares