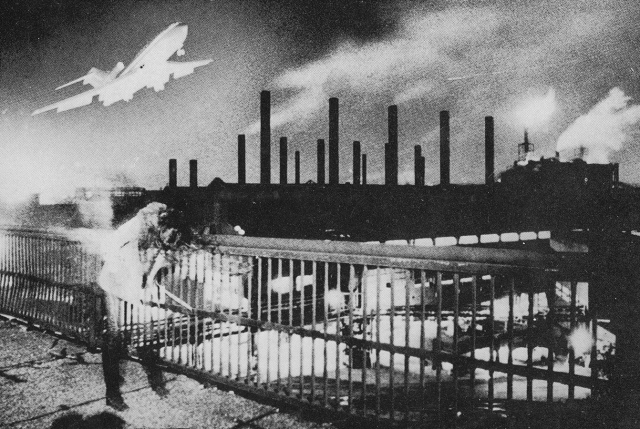

“Tonight we’re going to do a one hour set called Music from the Death Factory. It’s basically about the post-breakdown of civilization. You know, you walk down the street and there’s lots of ruined factories and bits of old newspaper with stories about pornography and page three pin ups … and you turn a corner past the dead dog and you see old dustbins. And then over the ruined factory there’s a funny noise.”

Genesis P-Orridge at Throbbing Gristle’s debut performance

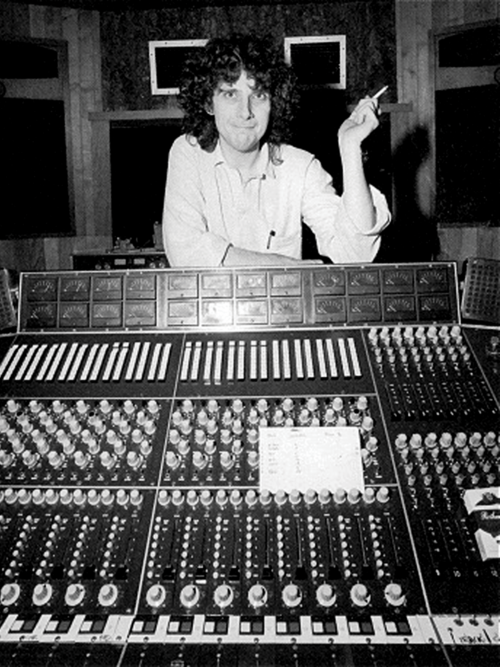

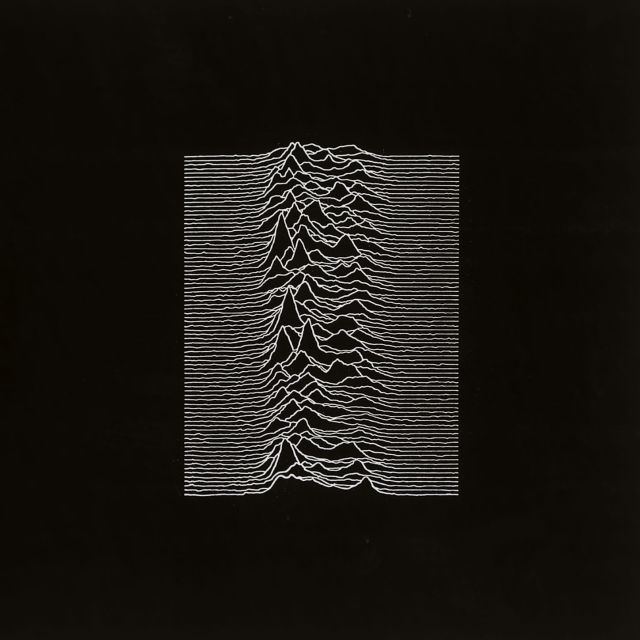

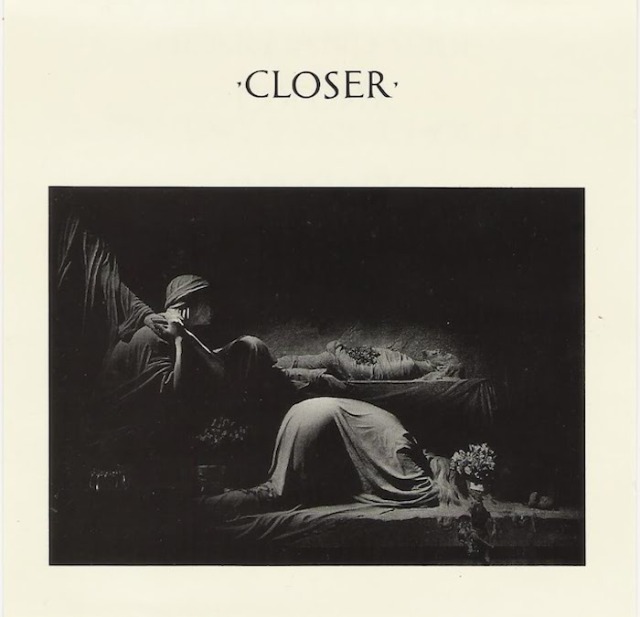

P-Orridge and his partner, Cosey Fanni Tutti, had relocated to London from Hull to continue their performance art activities as Coum Transmissions, but they rechanneled their energies into Throbbing Gristle, an avant-garde band (of sorts) that coexisted with the nascent punk scene. Named The Death Factory, the studio Throbbing Gristle worked out of was a vacant factory in Hackney, London. TG’s synth player, Chris Carter, summoned the sound of industrial waste; his cohorts dispensed with traditional rock song formats and concentrated on mirroring the decline of the urban landscape around them, although later they recorded danceable tracks like “United,” “Adrenaline,” and “AB/7A.” One of TG’s many admirers was Ian Curtis, lead singer for Joy Division, who, like P-Orridge, hailed from Manchester. Curtis was particularly taken with the TG track “Weeping” and befriended P-Orridge. P-Orridge maintains that he and Curtis plotted to have Joy Division and TG play a show together and then announce, at the gig’s conclusion, that they would quit their respective bands and work together from then on. P-Orridge took steps to book the concert in Paris, but it never happened. On the night of May 17, 1980, Curtis called P-Orridge and sang “Weeping” over the phone. Later that night he hung himself.

MANCHESTER

In early 1976, two Manchester art students named Howard Trafford and Peter McNeish read a review of the Sex Pistols in NME. Seeing the quote “We’re not into music, we’re into chaos,” they took off for London to check the band out. “We thought they were fantastic: it was, we will go and do something like this in Manchester,” they said, as quoted by Jon Savage in his punk history England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond (1992). Trafford and McNeish formed their own Sex Pistols–styled band, the Buzzcocks, and changed their last names to Devoto and Shelley, respectively. Eager to play out, they secured a space above Manchester Free Trade Hall and booked the Pistols to headline; their bandmates ultimately backed out, but the Pistols came and did the gig anyway. Brian Eno once said that not many people bought the first Velvet Underground LP when it came out, but everyone who did went out and formed a band; the same could be true of the audience for the Pistols gig in Manchester. Audience members included Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook of Warsaw, who started Joy Division and, later, New Order; Tony Wilson, who founded the venue the Factory and then the label of the same name; Morrissey, who went on to form The Smiths; future members of A Certain Ratio; and Martin Hannet, who would become Factory’s house producer. Soon Manchester had become a punk center second only to London. As Jon Savage has written in England’s Dreaming,

Mancunian punk subculture had developed in a degree of isolation, away from the capital [London]’s media spotlight: Manchester’s proud regionalism seemed to offer greater potential. “You didn’t need bondage trousers and spiky hair to be a Punk in Manchester,” says Malcolm Garrett. “It was more a question of your attitude. Everyone got their clothes from the Salvation Army or the antique clothes market. Coming to London to see the Ramones, I was astounded at how fashion-oriented it was. It was more home made in Manchester; people aren’t as cool there as they are in London. There, everyone is on the guest list: in Manchester you get dressed up, you go out to have fun, and you get wild.”

More than Liverpool or Glasgow, Manchester was an ideal Punk community, having, to some degree, put the ideals of autonomy into practice. “The reason Manchester happened was that they had undisputed talent in a number of fields,” says Garrett, “the music, the management, the journalists, designers and photographers. … There was a professional infrastructure, but it was so small it was like a village community. You felt you were in control.”

Local independent labels included Tosh Ryan’s Rabid, which released the first records by Slaughter and the Dogs and John Cooper Clarke, the Buzzcock’s New Hormones, and Valer. The city had new groups, poets, graphic artists, clubs, clothes shops, and fanzines such as Paul Morley’s Girl Trouble and Pete Shelley’s Plaything.

Manchester was a decaying industrial town, “the birthplace of the bouncing bomb, railways, and the computer,” as noted in the film 24 Hour Party People, an amusing look at the city’s 1976 to 1992 pop scene through the eyes of Tony Wilson. In his engaging study of rave culture, Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Club Culture (1998; published in the U.S. in a different version as Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture), Simon Reynolds has written,

Manchester has long been Britain’s number two Pop City after London. But in the post-punk era the city’s musical output tended to be synonymous with the unpop hue of grey: The Buzzcocks’ melodic but monochrome punk ditties, The Fall’s baleful transigence, Joy Division’s angst rock, New Order’s doubt-wracked disco. Dedicated to their own out-of-time, sixties notion of Pop, The Smiths defined themselves against contemporary, dance-oriented chart fodder. … Morrissey railing “burn down the disco / hang the blessed DJ.” The crime? Playing mere good-times music that said “nothing”, lyrically, about real life.

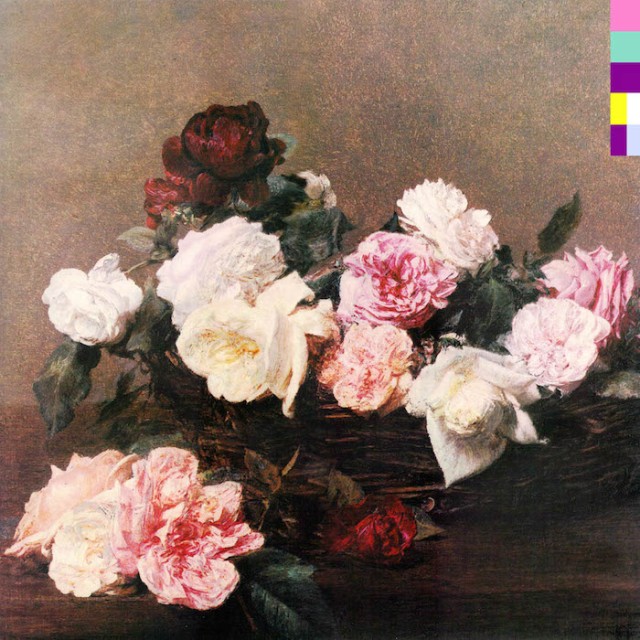

But the foundations laid by the Buzzcocks and Tony Wilson proved solid. New Order rose from the ashes of Joy Division, stayed on with Factory, remained in Manchester, had several dance club hits, and opened a new venue with Wilson, the Hacienda. Reynolds again: Thanks to house clubs like the Hacienda, Thunderdome, and Konspiracy, Manchester transformed itself into “Madchester”, the mecca for 24-hour party people and smiley-faced ravers from across Northern England and the Midlands. By 1989 the famously grey and overcast city had gone day-glo; Morrissey-style miserablism was replaced by glad all-over extroversion, nursed by a diet of “disco biscuits” (Ecstasy, or E).

With its combination of bohemia (a large population of college and art students, and the biggest gay community outside of London) and demographic reach (around fifteen million people live within a couple of hours drive of the city centre), Manchester was well placed to become the focus of a pop cultural explosion. … Converted from a yachting warehouse showroom, the Hacienda was initially dystopian and industrial in ambience. The atmosphere perked up when DJs like Martin Pendergrast and Mike Pickering started to add house to the mix. …

The quintessential Manchester band of the era was the Happy Mondays, who eased the city’s traditionally harsh rock sounds with funk and a nonstop dosage of E. They too recorded for Factory and were produced by Martin Hannett. Wilson hyped the Mondays as the new Sex Pistols, although Reynolds’ comparison to the Butthole Surfers, a traveling, shambling carnival of excess, rings far truer. Still, Tony Wilson’s prescience in signing both Joy Division and the Happy Mondays, ushering in two separate British music movements (post-punk and rave) by adapting to the changing times, confirms his status as a pop visionary.

But unlike many shorter-lived regional music scenes, it was too much success, rather than too little, that unraveled Manchester. The seemingly endless E-high eventually led to a crash. Mondays leader Shaun Ryder’s drug problems overtook him and the band. Drug gangs began infiltrating the Hacienda, and narcotics-related violence eventually forced it to close. New Order, however, continued to record and perform through the ’90s; The Buzzcocks split in 1981, reformed in 1989, and are still together.

CLEVELAND

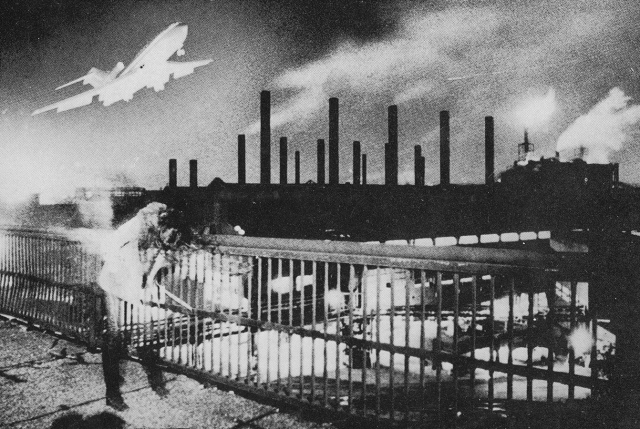

By 1968, the Velvet Underground had never performed in their home base, New York City. Instead, they’d toured the United States, making regular stops in Cleveland, where they played numerous shows at La Cave, a small basement club on Euclid Ave. near Case Reserve University. Two local teenagers, Peter Laughner and Jamie Klimek, were always present at those gigs. Klimek even tape-recorded several Velvets performances; some of the tapes have since been released as bootlegs. The pair, who were both guitarists, would find their way backstage, where they listened to Lou Reed ruminate on life on the road, astrology, music, whatever. The Velvets made a deep impression. Jamie went on to form the Mirrors, Cleveland’s first band to do Velvets and Stooges covers, which they combined with Syd Barrett–influenced originals. Peter went through several different bands before landing in Rocket from the Tombs, an initially Zappa-influenced group led by David Thomas then going by the name of Crocus Behemoth. Rocket became more metal with the arrival of Laughner, and began doing Velvets and Stooges songs, too. Peter and David went on to form Pere Ubu after Rocket collapsed. On its early singles (some of which originated as Rocket material) and classic first album, The Modern Dance, Ubu wedded rock song forms to bleak soundscapes forged by Allen Ravestine’s synthesizer, a kind of dystopian answer to Brian Eno’s jagged synthesizer stylings in Roxy Music’s glitter rock. As Jon Savage has put it,“

Living within a dying industrial city, the group celebrated their environment with a sense of wonder, as Thomas has explained: “In the Flats where the coke cars line up on the railroad tracks and the gas flames come out from under the ground, it’s just acres of flame coming out of the ground, and green smoke. The Clark Bridge is surrounded by blast furnaces. The sky goes green and purple. It wasn’t only Cleveland as a particular location, but to get a perspective you need to be able to see those views … you’d go by the steel mills and there was this very powerful electrical feeling, combined with a particular sound in the air that conjured up a whole set of visions with it.”

And around Ubu a whole scene sprang up. There were punks (The Pagans and The Dead Boys, founded by three other former Rocket members), progessives (The Styrenes, a transmogrification of Mirrors), and weirdos (Ex-Blank-Ex, a group led by John Morton, formerly of Electric Eels, who were contemporaries of Mirrors/Rocket and still stand as one of the most scabrous ur-punk outfits in history). By the late ’70s Cleveland hosted several venues to accommodate the music, a great record store and label called Drome, and a fantastic periodical, CLE, which comprehensively documented the scene. But at the same time the scene started to fragment.

Laughner died from alcoholism in 1977, at the age of 24. Pere Ubu signed first with Mercury, then Chrysalis, but failed to make commercial inroads and broke up (though they reunited in the late ’80s and continue performing forming to this day). Several people moved to New York looking for a big break. The Styrenes relocated there but never achieved success; Klimek eventually returned to Cleveland. The Dead Boys made a couple of albums for Sire but never moved beyond their cult status. Adele Bertei and Bradley Field became stars of New York’s No Wave scene as members of the Contortions and Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, respectively, but remain footnotes in rock history (Field died in the late ’80s). Anton Fier, a talented drummer who performed with Laughner, Ex-Blank-Ex, the Styrenes, and a later edition of Pere Ubu, perhaps did the best of any of the Cleveland-to-NYC migrants, becoming the original drummer for the Lounge Lizards and the Feelies, and later the leader of his own supergroup The Golden Palominos. Incredibly, Rocket from the Tombs reformed in 2003 and has been touring the U.S.Asking why Cleveland failed and Manchester succeeded is like asking why indie rock bands Mission of Burma, Black Flag, Hüsker Dü, and Dinosaur Jr. failed and Nirvana succeeded, or why every boy/girl guitar/drum duo on Olympia Washington’s K record label failed and the White Stripes succeeded. Like Manchester groups, Nirvana and the White Stripes had a strong infrastructure—the songs, sound, look, work ethic, and attitude were solid. Success demands a total package, and their predecessors were usually lacking in one area or another, no matter how strong they were in other areas. Mission of Burma never really toured, and failed to attract a major label; Black Flag toured plenty but alienated the music industry early on, cementing their underground status until they finally dissolved; Dinosaur and Hüsker Dü had the hooks but not the looks. Like Shaun Ryder, Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain combined two formerly mutually exclusive musical styles (punk and classic rock, in his case) at the right time, gave voice to a zeitgeist with his lyrics, and looked like every kid in his audience. Like Ryder, he had a drug problem; like Curtis, he subscribed to the ethos of an early death as the secret password to the eternal rock pantheon.

Ultimately Manchester’s ticket to the big time was not music that reflected its urban landscape, but music that reflected a wave of optimism traceable to Thatcher-era England’s economic boom and the fall of Communism. (And certainly not confined to the U.K.; as the Happy Mondays ascended, so did Athens, Georgia’s, R.E.M. R.E.M.’s early songs were lyrically obtuse but referred to “Shiny Happy People” at the same time that the Mondays were singing about “24 Hour Party People.”) Dance has always paved the road to prosperity for music cities. Think of Detroit, whose economy collapsed with the auto industry—it’s produced aesthetically and commercially definitive dance music during the ’60s (Motown), ’70s (Parliament/Funkadelic), and beyond (as a capital of house and techno). Consider also the South Bronx, the epitome of urban ruin at the end of the ’70s, which generated hip-hop, now the biggest music in America—the punk rock that blossomed at the same time on the less sketchy East Village streets a few miles to the south has only become marketable in the last decade. Until hip-hop, ’70s New York was the home of non-escapist rock. Just as the Velvets sang, “I’ll be your mirror, reflect what you are,” Suicide’s Alan Vega recently told me that he used to give the band’s audience “the street back in their face—they came in to get entertained, we were just giving them the truth.” The Velvets in particular opened the door for this kind of reality-based music making, replicating the steely sounds of the subway and other heavy machinery, but this approach has never led to mass popularity the way that music that literally dances all over your problems does. The two CBGB bands that had hits had to employ dance beats to do so (Blondie and Talking Heads). Recent New York sensations like the Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and the Rapture may bring the noise (to varying degrees), but also demand a groove.

The rock press has been on the lookout for cities with a vibrant rock scene since early ’60s Liverpool and late-’60s San Francisco set the standard. Seattle was a breakout in the late ’80s and early ’90s with Soundgarden and Nirvana; its perpetually rainy backdrop was glamorized by grunge, just as London’s was by the British Invasion in the ’60s and Manchester’s by rave in the ’80s. Subpop, originally a fanzine and then a label, is perhaps America’s Factory, though it has yet to be bankrupted by one band’s recording budget (as Factory was by the Happy Mondays’ fourth LP). In Seattle’s wake came Chapel Hill (a nice Southern college town in the Athens tradition that boasted a solid center with the band Superchunk and its label, Merge, which still exists today), Chicago (Liz Phair, Smashing Pumpkins, and Urge Overkill finally put the Midwestern burg on the music map in the early ’90s, and Tortoise helped keep it there as grunge gave way to post-rock), Athens again (with Olivia Tremor Control, Neutral Milk Hotel, and the Elephant 6 collectives, bands that lived together on the cheap and tried to assemble home-recorded equivalents to Pet Sounds or Sgt. Pepper). True, these scenes all sprang from a confluence of low rents, boredom, college students, and surroundings with varying degrees of bleakness. But there’s never been any kind of creative wellspring in such dead-end towns as Hartford, Connecticut; Newark, New Jersery; Toledo, Ohio; Gary, Indiana; Albuquerque, New Mexico; San Jose, California (unless the Doobie Brothers or the Count Five count); and many more. It takes more than economic and/or social depression to spark creative activity as an act of defiance, distraction, or survival.

He called his studio the Factory—conceiving it as a new kind of factory, one that constantly produced art, film, and music (the Velvet Underground) instead of the ultimately disposable products usually associated with the term. And it took the form of a crumbling loft, first one on 47th Street, then another in Union Square, that was furnished with whatever Warhol’s assistant Billy Name picked up on the street. For his part, Tony Wilson came up with the name “factory” after seeing a sign saying “Factory closed” and wanting to build a factory “that was open,” but he was also very conscious of Warhol. Two years before Wilson, Throbbing Gristle were going to name their label “Factory” in reference to Warhol, but they rejected it as too obvious, and used Industrial Records instead.

Malcolm McLaren, the manager of the Sex Pistols, to some extent borrowed Warhol’s ideas of sponsoring a band and establishing a circle of freaks (compare the names of Warhol hangers-on Rotten Rita, International Velvet, and Pope Ondine to Johnny Rotten, Sue Catwoman, or the Bromley Contingent’s Siouxsie Sioux and Billy Idol). Warhol’s beautiful silkscreens of movie stars, soup cans, and flowers set the precedent here, too—his work’s “don’t worry be happy” message to his immediate predecessors, the dour Abstract Expressionists, is a precursor to the Happy Mondays’ message to the Smiths (and came at the start of one of the longest economic expansions in U.S. history). His work inserted a silver lining into the mundane in a way that Pere Ubu and Throbbing Gristle’s celebrations of industrial sounds did not.

The scenes in 24 Hour Party People of Joy Divison performing reveal intense, almost frightening music-making but also people dancing and having fun—both the audience and, in their own way, the band. Even the name Joy Division, though it was derived from the prostitution sectors of concentration camps, gave a cheerier appellation to a band with a musical and lyrical outlook that was bleak to the point of suffocation. Current bands like Interpol or the Liars, however, who conjure the sounds of Joy Division and Gang of Four, have dispensed with their forebears’ underlying sense of dread, reinventing post-punk as party music. Warhol’s ideas were spread like seeds by his fame and activities throughout the world, and bore fruit in places like Manchester and Cleveland, but it may be reasonable to say that such music scenes were only possible during his lifetime.

© Alan Licht & Issue Magazine