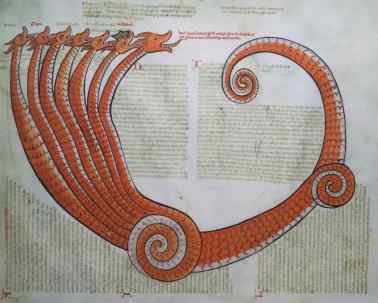

A picture from Joachim’s ‘Liber Figurarum’

* * *

The whole historical vision drawn by Joachim of Fiore seems to take its inspiration from these words contained in St. John’s Gospel: “When the Consoler comes, whom I will send to you from the Father, The Spirit of truth who comes from the Father, he will testify on my behalf” (John 15, 26).

Philosophers and scholars have long reflected on the three Ages revealed by Joachim, often putting his teachings on the same ground of contemporary philosophy.

In Gioacchino da Fiore – Attualità di un profeta sconfitto (Newness of a defeated prophet) Massimo Iiritano has written: “The feeling of God’s death, which is ‘the essence of modern times religion’, is the main prophecy of the Christian Religion itself, the extraordinary truth it cannot renounce. In Christ, actually, God himself died: in an absolute kenosis of his own transcendence which signs his destiny of involvement in the saeculum. This is something which cannot be eluded. This is the ‘speculative Good Friday’ of which philosophy as knowledge of the Whole has been able to recognize the truth: going beyond, in an Aufhebung through which the modern ‘human too human’ hybris finds an expression, opening the road to the actual secularization. In this way that space forecast in Joachim’s third status comes to be progressively invaded by modernity which keeps getting further from the original and undeniable idea of the escathon and keeps losing the only possible religious meaning of it”.

Unfortunately contemporary thinkers assumed the right to talk about the Scriptures without taking into account the Scriptures themselves. This might be the reason why they leave such large room for speculations – or aufhebung – of any kind. Let’s read the New Testament, far and wide, we shall not find a word about “the death of God”, since such is a concept given out by Nietzsche and no one else. No surprise whether it could be so widely accepted by nowadays mentality and, by the way, no need to stretch its meaning to find straight in the Revelation a suitable explanation to it: “The beast was given a mouth uttering haughty and blasphemous words” (Rev. 13, 5).

Furthermore, what Iiritano seems here to forget, is the mysterious relation between the Father and the Son of Man which finds its highest expression in the Gospels. This has been happening very often all along the history of contemporary philosophy: such lapse probably related to the problematic inheritance of the Trinity Dogma.

The Son of Man “enters into his glory” and does so by fulfilling the Scriptures (Lu. 24, 25-27): does it make sense to say that, in him, God has died? According to Iiritano, philosophy has recognized the truth of the so called ‘speculative Good Friday’, but since, as we repeat, the New Testament never says or implies that God has died, would not it be the case to say that such truth has not been recognized but invented by contemporary philosophers?

Iiritano, whose reflections can be here and there worthy of all interest, inherited all his main topics by the Italian Bible scholar and philosopher Sergio Quinzio. Among these: history seen as an immanent race towards the escathon, during which all transcendence and Metaphysics come to be reshaped if not denied. According to Quinzio, The Gospels have been interpreted as transcendental works only because of the influence of Greek philosophy.

Countless of his aphorisms hint at such concept.

Beyond any possible Platonism, why are the Gospels about a Heavenly Father who lets his rain drop onto the righteous and the unjust ones? and why are Gospels about a Heavenly Kingdom and not about a kingdom in which purification have no importance, when allegedly they leave no room for transcendence?

In Quinzio, a quite prepared and deep thinker, I could not ever find any answer to these questions.

Modern sensitivity might have lost all familiarity with transcendental language and all capacity to find a relation between spatial and temporal symbolism, nevertheless Dante Alighieri himself dedicated his main work to such marriage. Actually the Divine Comedy tells about his spiritual journey upwards in the Heavens and, at the same time, about his journey towards “the convent of the white stoles” [See Paradiso 30, 129].

* * *

Joachim of Fiore himself wrote: “The acts of the second status are more spiritual than the ones of the first, but less spiritual than the ones of the third therefore in the first intelligence one can only partially go beyond the letter, while in the second [in the spiritual intelligence, an] one can go beyond the letter completely and perfectly” (Enchridion super Apocalypsim, VIII).

Are not these words meant to declare the spiritual intelligence of a higher kind than the literal one? Is there an idea of hierarchy and transcendence, in them?

Here we are faced with what many thinkers do not seem to understand: the promise of the Apocalypse cannot be depicted as a simple immanent concept, since a deep mystery lies between such promise and us: a mystery which can be revealed only to those who gradually become worth that. Joachim seems to remind us exactly this by writing: “Now the time has come – the exact time – for the hidden mysteries of this book to be revealed, the time in which no one is allowed to boast with pride for knowledge, but it is more worthy instead to turn our mind on the shipwreck which threatens us” (Enchridion super Apocalypsim, VIII).

* * *