“The Charming of Mandara Giri” 1605 Natural pigments on paper. Image courtesy of Museum Puri Lukisan

“The Charming of Mandara Giri” 1605 Natural pigments on paper. Image courtesy of Museum Puri Lukisan

Imagine you are a master Balinese painter, and your King has recently commissioned you to create a work. As you sit down in front of a large cloth stretched upon a wooden frame with a pencil in hand, for a moment you contemplate the composition before beginning to sketch. The year is 1723. What would go through your mind?

Possibly you hear the clash and bangs of metallic instruments of a Balinese ensemble. You visualize the cloth in front as a giant screen, with an audience seated on the opposite side. And you imagine yourself as a dalang – a master puppeteer – manipulating puppets while bringing to life a mighty Hindu religious epic during a wayang kulit shadow theater play.

The roots of the wayang puppet theater, one of the original story telling methods in the Balinese culture may be traced back over 2000 years to the Indian traders who settled in Nusa Antara (Indonesia prior to being known as the Dutch East Indies) bringing with them their culture and Hindu religion. The wayang or classical style of Balinese painting is derived from the imagery that appears in this medium.

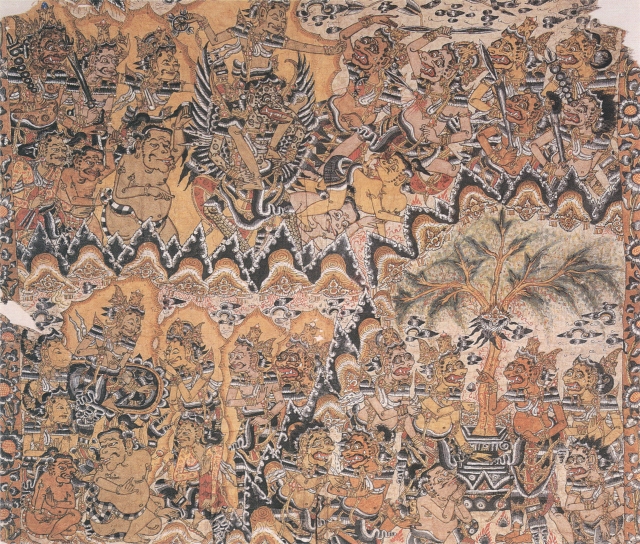

“The Death of Abismanyu”

“The Death of Abismanyu”

The paintings were made on processed bark paper, cotton cloth and wood and were used to decorate temples, pavilions, and the houses of the aristocracy, especially during temple ceremonies and festivals. Originally the work of artisans from the East Javanese Majapahit Empire (13-16th Century), this style of painting expanded into Bali late in the 13th century and from the 16th – 20th centuries, the village of Kamasan, Klungkung, was the center of classical Balinese art, and hence the Kamasan paintings.

The original works were a communal creation, the master artist shaped the composition, sketching in the details and outlines and apprentices added the colors. These works where never signed by an individual and considered as a collective expression of values and gratitude from the village to the Divine. Colors were created from natural materials mixed with water, i.e iron oxide stone for brown, calcium from pig bones for white, ocher oxide clay for yellow, indigo leaves for blue, carbon soot or ink for black. Enamel paint introduce by the Chinese a few hundred years ago were used on wooden panels of pavilions and shrines, or even upon glass.

The highly detailed, sacred narrative Kamasan paintings play an essential role within the Balinese culture functioning as a bridge communicating between two worlds, the material world humans inhabit and the immaterial world of the divine and demonic forces. The artist functions as a medium translating the esoteric and invisible into a comprehendible visual language and bringing greater understandings to the mysteries of life according to scriptures and philosophies. According to Dr Adrian Vickers, Professor of SE Asian Studies at Sydney University, “The key to Kamasan painting’s sense of beauty is the beautiful flow of line and the pure flat figuration.”

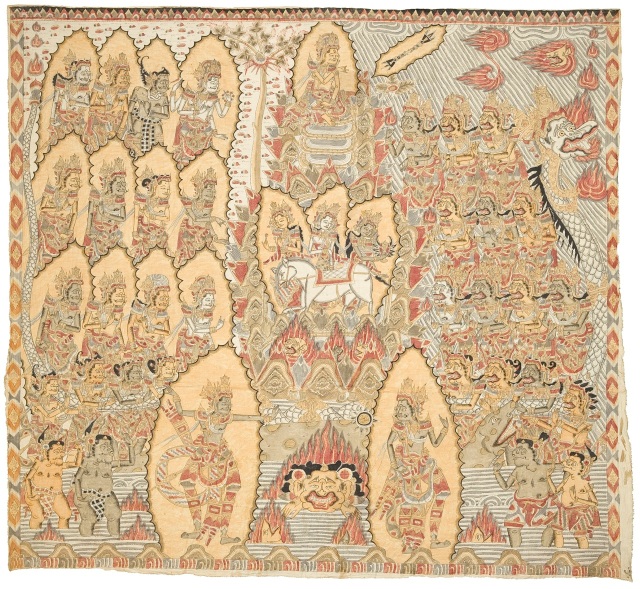

A Modern Kamasan Painting “The Turning of Mount Mandara” Mangku Mura 1973 Image courtesy of David Irons.

A Modern Kamasan Painting “The Turning of Mount Mandara” Mangku Mura 1973 Image courtesy of David Irons.

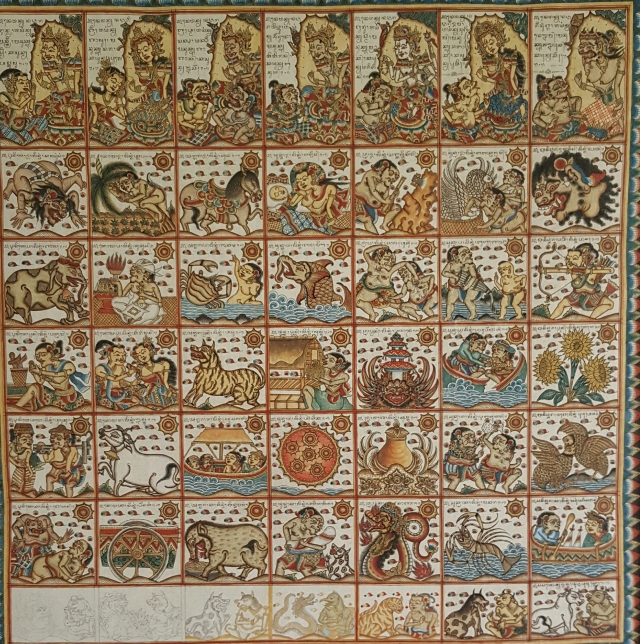

For foreign audiences the paintings, however, present difficulties in their understanding. Without a concept of the landscape in Balinese paintings it’s about an arrangement of items on a flat surface akin to the shadow puppets against the screen in shadow theater. Unlike Western modern art where paintings generally have one focal point there is no central focal point to read the Kamasan narratives. Most of the paintings have multiple stories that may be read in all areas around the composition.

Looking at painting it is full with visual information to the extent that nothing stands out. Tight, generalized, often repetitive patterning, often of decorative motifs, and combinations of graphic patterns are distributed all across the surface leaving little or no blank areas. Ornamental elements, rocks, flowers motifs and painted borders indicate Indian and Chinese influence from Chinese porcelain and Indian textiles.

“Adherence to established rules about the relative size of parts of figures related to measurements in the human body – in the Balinese perspective each measurement is seen as a human manifestation of elements that exist in the wider cosmos. Correctness of proportions is part of being in tune with the workings of divine forces in the world. Colors are also codified.” says Adrian Vickers in his book Balinese Art Paintings & Drawings of Bali 1800-2010. “Form evokes spirituality.”

“Kumbakarna Attacked by Monkeys” Date Unkown. ARMA

“Kumbakarna Attacked by Monkeys” Date Unkown. ARMA

The two dimensional Kamasan compositions generally depict three levels, the upper level is the realm of the Gods and the benevolent deities, the middle level occupied by kings and the aristocracy, and the lower third belongs to humans and demonic manifestations. Details in facial features, costumes, body size and skin color indicate specific rank, figure or character type. Darker skin and big bodies are typical of ogres, light skin and finely portioned bodies are Gods and kings. Rules control the depiction of forms; there are 3 or 4 types of eyes, 5 or 6 different postures and headdresses. The position of the hands indicates questions and answers, command and obedience.

The narratives are from the Hindu and Buddhist sacred texts – the Ramayana, Mahabarata, Sutasoma, Tantri, also from Panji – Javanese-Balinese folktales and romances. Astrological, earthquake and birth charts are also depicted. Major mythological themes are rendered in great symmetry, while these paintings contain high moral standards and function to express honorable human virtues to society with the intent to encourage peace and harmony. A beautiful painting communicates balance, aesthetically and metaphorically, and is equated to the artist achieving union with the divine.

Traditional Kamasan painting is not static and keeps evolving as subtle changes have occurred over time as each artist has their own style, composition and use of colour. It is common that new works regularly replace old and damaged works and hence Kamasan painting is an authentic living Balinese tradition.

“Bharata Yudha” 1969 – Tjokorda Oka Gambira

“Bharata Yudha” 1969 – Tjokorda Oka Gambira

Where to See Kamasan Paintings in Bali:

Museum Puri Lukisan, Jalan Raya Ubud, Bali

Tele: +62 361 971159

Open Daily 9am – 5 pm.

ARMA Museum, Jalan Raya Pengosekan, Ubud, Bali

Tele: +62 361 975742

Open Daily 9am – 5 pm.

Neka Museum, Jalan Raya Sanggingan, Campuhan, Ubud, Bali

Tele: +62 361 975074

Open Daily 9am – 5 pm

Nyoman Gunarsa Museum of Classical & Modern Art

Jl. Pertigaan Banda No. 1, Takmung, Banjarangkan, Klungkung, Bali.

Tele: +62 366 22256

Open Daily 10 am – 5 pm.

Palalintangan – Astrological Chart

Palalintangan – Astrological Chart

“The Gods of Eight Attacking Garuda” – Pan Seken

“The Gods of Eight Attacking Garuda” – Pan Seken

Words & Images (unless specified): Richard Horstman

Follow Richard on Instagram @lifeasartasia

*Author’s note: No part of the written content of this website may be copied or reproduced in any form, including article links uploaded to other websites, for any commercial purposes without the written permission of the author. Copyright 2024

One reply to “Balinese Kamasan Paintings”