Auxiliar verbs and the conjugations - modi (moods) and tempi (tenses) of the verbs.

I think it’s time to introduce a little the verb’s conjugations, starting with the 2 most important verbs, avere (to have) and essere (to be), aka the auxiliar verbs of the italian language. They both belong to the 2nd conjugation of the verbs and they are especially used to make the composed tenses of the other verbs (reason why are called auxiliar) or in the passive forms (in this case, you might find also the verb venire = to come, but I will explain this next time).

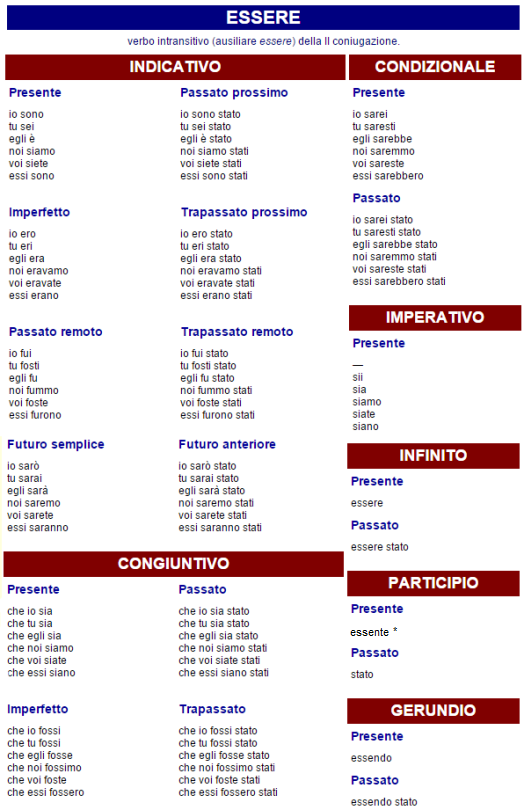

Let’s see the conjugations of the verbs avere and essere and make a few examples of different tenses also with other verbs.

=> There is a very good website here in which you only need to write down the infinitive form of a verb in italian (but actually I tried with a participle and a subjunctive and it works anyway) and click on the button “coniuga!” (conjugate) to have a complete conjugation of that verb in every tense in italian. So, if you need any conjugation of a verb immediately, I guess you might find it useful (also to start seeing how the auxiliar verbs work with the other verbs, if you want). Here you have two samples of the conjugations of the verbs essere and avere, taken from there:

*I had to correct the present participle (participio presente) of the verb to be (essere), because the website showed “ente” but the correct (and more used) form is “essente”. So, if you’ll try the website and see another thing for the verb to be there, don’t worry.

A little nomenclature:

- the names in red are called MODI (moods; singular: modo = mood)

The modi, are:

. indicativo (indicative), used for something certain, for reality, for impartial opinions.

. congiuntivo (subjunctive), used to express possibilities, wishes, fear, doubts and personal opinions.

. condizionale (conditional), used with possible facts and actions, depending on a condition.

. imperativo (imperative), used to command, to warn, to scold, to beg

. infinito (infinitive), used when you don’t need to refer to a person or a tense, it just refers to the action itself.

. participio (participle), mostly used as an adjective, but also to form past tenses. It refers to an action related to someone.

. gerundio (gerund), related to the way, the time, the reason or how an action happens compared with the one in the main clause or the clause the gerund depends from.

- the names in blue are called TEMPI (tenses; singular: tempo = tense)

All of these have a specific use based on the tense of the sentence but also on how it is built.

The tempi are:

. In modo indicativo :

-presente (present simple), used to express something happening in the moment.

Io scrivo una lettera. | I write a letter.

-passato prossimo (present perfect = present simple + past participle), used to express something that happened in the past, but not a very far past from now.

Ieri alle sette di sera, Raffaella ha scritto una lettera. | Yesterday at 7pm, Raffaella wrote a letter.

-imperfetto (imperfect), used to refer to something happened in the past, but not ended yet (differently from the passato prossimo).

Ieri alle sette di sera, Raffaella scriveva una lettera. | Yesterday at 7pm, Raffaella was writing a letter.

-trapassato prossimo or piucheperfetto (pluperfect = imperfect + past participle), used to refer to something happened before the *imperfect* or before something happened in the past.

Ieri ho ricevuto quello che avevo chiesto il giorno prima. | Yesterday I received what I asked for the day before.

-passato remoto (remote/distant past), used to express something happened in the far past that has no more correlation with the present (differently from the passato prossimo).

Io parlai a mio padre. | I have talked with my dad.

-trapassato remoto (past perfect = remote past + past participle), used to express something happened before something happened in the *passato remoto*.

Dopo che fummo arrivati, entrammo. | After we had arrived, we went in.

-futuro semplice (future simple), used to refer to something that will happen in the future or even just possible present and future facts.

Marina domani partirà. | Marina will leave tomorrow.

-futuro anteriore (future perfect = future simple + past participle), used to express facts that will for sure happen and end in the future or doubts.

Domani a quest’ora, Marina sarà partita. | Tomorrow by this time Marina will have left.

Marina non c’è, sarà uscita. | Marina isn’t here, she might be outside.

. In modo congiuntivo :

-presente (present), used especially in a subordinate clause to express unreal events.

Spero che voi siate sinceri. | I hope you are honest.

-passato (past = present + past participle), to express facts already ended, seen as unreal or irrelevant.

Tutti pensano che io sia andata via. | Everybody thinks I went away.

-imperfetto (imperfect), used in the subordinate clause when the main clause express uncertainty - (if sentences)

Speravo che tu fossi sincero. | I hoped you were honest.

-trapassato (past perfect = imperfect + past participle), used to express an unreal fact happened in the past before a moment in the past - (if sentences).

Io credevo che tutti fossero già arrivati. | I believed that everybody would have already arrived.

The other verbal moods only have presente (present) and passato (past) tenses, and the passato is usually made with the present + the past participle.

There is an exception: the case of the present participle: it only differs from the past participle because it has a different suffix. The present participle usually ends in -ante (1st conjugation) and -ente (the others conjugations), while the past in -ato (1st conjugation), -ito (3rd conjugation), and it might change a bit more for the 2nd conjugation: in general, there is not a perfect rule, not for the present and not for the past.

Examples:

leggere (to read): leggente (pres. part.) - letto (past part.)

sognare (to dream) : sognante - sognato

scrivere (to write): scrivente - scritto

uscire (to go out): uscente - uscito

ridere (to laugh): ridente - riso

partire (to leave): partente - partito

——> As you can see from the table, in italian the verbo essere (verb to be) is its own auxiliar, as the verbo avere (verb to have) is its own.

Io sono = I am ; Io sono stato = I have been

Io avevo = I had ; I avevo avuto = I have had

I guess this can be enough for now. Just let me know if something isn’t clear or if I messed up with something in your opinion (it might be, the post is rich and quite long), so we can speak about it together.

I will explain the If sentences, the transitivo/intransitivo (you can read it in the tables), the verbi servili and the passive form asap. And also I might try to show you an example of analisi logica and grammaticale (logical analisis and grammatical analisis) we usually do in school to learn italian grammar (and I guess people studying italian have to do them too - I don’t envy you at all! I know well what that is about.. meeh!).