Episode 4 of Fosse/Verdon takes us to the 1973 post-Cabaret period when Fosse was the hottest ticket in town, winning the directing trifecta of an Oscar, an Emmy, and a Tony. (He’s still the only person to have won all three in a single year.) But does the cocktail of huge professional success, copious meaningless sex, and large quantities of Seconal, Dexedrine, and alcohol make him happy? What do you think? Verdon’s career, meanwhile, has gone off the boil, but she is finding new personal happiness despite her friend Joan Simon’s terminal illness.

Bob’s Big Success

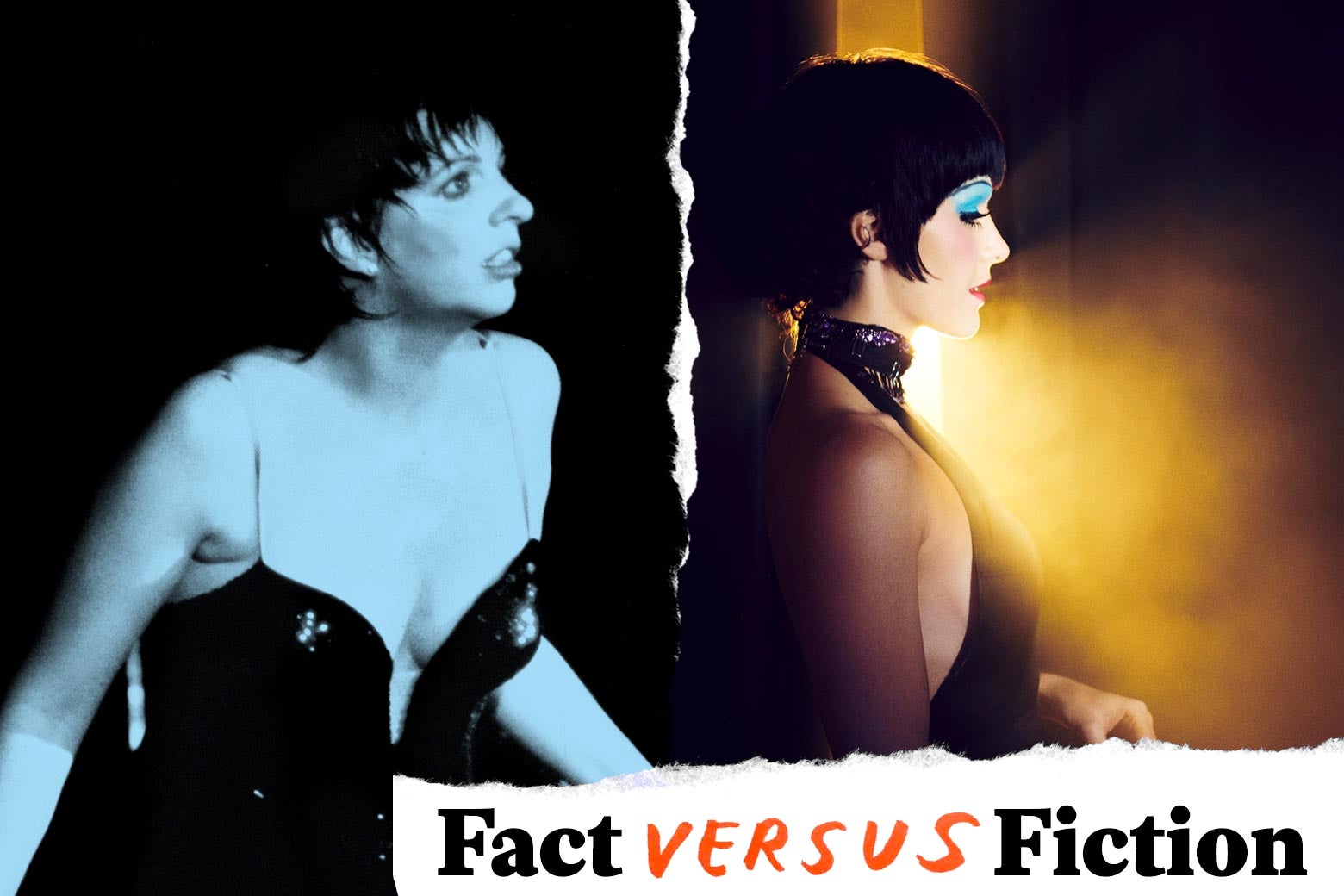

Along with the Best Director Oscar for Cabaret, Fosse won directing and choreography Tony Awards for Pippin and Emmys for producing, directing, and choreographing Liza Minnelli’s TV special Liza with a Z. Cabaret won eight out of the 10 Oscars it was nominated for, a record for the most Academy Awards won by a film that did not go on to win Best Picture. The reviews were every bit as good as Paddy Chayefsky suggests in the episode, with the New York Times declaring, “ ‘Cabaret’ is one of those immensely gratifying imperfect works in which from beginning to end you can literally feel a movie coming to life,” while Roger Ebert wrote “instead of cheapening the movie version by lightening its load of despair, director Bob Fosse has gone right to the bleak heart of the material and stayed there.” Moreover, unusually for such a dark movie, it proved popular with audiences, topping box-office charts for four weeks.

The Fosse touch was particularly crucial to Pippin’s success (it’s the 36th longest-running Broadway show). As theater historian Scott Miller wrote, “The show now has a reputation for being merely cute and harmlessly naughty; but if done the way director Bob Fosse envisioned it, the show is surreal and disturbing.” After these two triumphs and then the acclaim for Liza with a Z, Fosse’s phone was ringing with offers from producers so frequently he had to disconnect it.

Bob the Sexual Harasser

In the episode, Bob puts the moves on several of his dancers, inviting them to give him feedback on the rough cut of the Liza TV special, a more sophisticated version of the old “come up and see my etchings.” On the whole they are flattered and cooperative, except for one who says she just wants to be friends and, when Bob walks her home and literally presses himself on her, knees him in the groin. After this, he criticizes her performance relentlessly in rehearsal and ultimately gives her featured spot to another holdout, the talented Ann Reinking (Margaret Qualley), of whom Gwen perceptively observes, “She’s too good for you. She knows she doesn’t have to visit your hotel room to get the solo.” Sherry, the original dancer desperate to get her solo spot back, gives in and invites Bob for a drink.

Fosse’s inclination to view the chorus line as his personal candy store was well-known. As an anonymous dancer told People magazine in 1980, “You can assume he’s going to try to make you. He tries with every girl and gets a fair percentage. He’s so casual. He doesn’t give you much respect.” The incident with the reluctant Pippin dancer is based on a real dancer. According to Martin Gottfried’s biography of the director, after Pippin dancer Jennifer Nairn-Smith, a Balanchine-trained ballerina, delivered a well-placed kick to discourage his advances, Fosse bullied her in rehearsal while still calling her regularly to set up a booty call. “It made me so nervous,” she told Gottfried. “I’m a ballet dancer, and you do what a choreographer says. You could drag me around the floor. I had no self-esteem.”

Even Fosse himself admitted as much, although he suggested the girls were responding to personal charm as much as his power over their careers, telling Rolling Stone, “I like to think I was a pretty good-looking guy, and I cared about the women and had a good sense of humor, but also I’d be a fool if I didn’t recognize that I had a certain degree of power over them. Directors are never in short supply of girlfriends.”

Bob’s Breakdown

At the height of his fame, his hotel room adorned with golden trophies, Bob is beset by visions of his nearest and dearest, including Gwen, telling him he’ll never be good enough and he’s a fraud. He steps out on the ledge of his hotel room window, but instead of jumping ends up at Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic, then the psychiatric facility of choice for New York’s smart set.

Just as much as his flirtations with women, Fosse’s flirtation with death was an open secret. As his biographer Sam Wasson observed, Fosse “had the jazzman’s crush on burning out.” In fact, when he first read the script of Pippin, Fosse recalled, he was “frightened by the naiveté of the concept, a boy seeking fulfillment … I said the boy must be tempted by suicide—I’m fascinated by suicide.”

We haven’t been able to verify whether Verdon did indeed have a new boyfriend called Ron (played on the show by Jake Lacy), or if a drunken Fosse tried to get into to the former marital bed with them in it. It is true that Fosse checked himself into Payne Whitney for depression after winning his third big award, but for no more than a long weekend.

That he actually went out on the ledge before doing so may be invention, but there is no doubt he thought about death, and the sequence where he is beset by friends stirring his doubts and insecurities may be the series’ own hat tip to Fosse’s thinly veiled autobiographical film, All That Jazz, in which a hospitalized director-choreographer confronts his own mortality and is visited by visions of significant others and casual lovers who remind him of his mistakes and misdeeds through the medium of—what else?—song and dance.

Joan Simon’s Illness

In the show, Gwen visits her close friend Joan Simon, who is in the hospital with a serious, though unnamed, illness. When Gwen starts talking about future plans, Simon cuts her off: She knows her illness is terminal and she’s not leaving the hospital. Gwen later asks Bob if he’s managed to visit Joan yet. When Bob, with typical vagueness, says he will and perfunctorily asks how Joan is doing, Gwen responds, “She’s got a month left to live,” which finally penetrates his bubble of self-absorption.

Despite the unreality conferred by depicting Simon with glossy hair and perfect skin while at death’s door, she did in fact die of bone cancer in 1973 at the age of 41. Typically, her obituary in the New York Times had the headline “Neil Simon’s Wife Is Dead.”