The United States vs. Billie Holiday focuses on the later period of the legendary jazz singer’s career up until her death in 1959—and the U.S. government’s relentless persecution of her throughout that time. Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks based her screenplay for the new movie on Johann Hari’s bestseller Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs, specifically on the chapter about the federal agents who targeted Holiday. Though the movie’s timeline jumps between different points of Holiday’s career and glimpses at the wider war on drugs (as well as the early war on jazz music), it focuses on how much Holiday was exploited by the predatory people and systems around her.

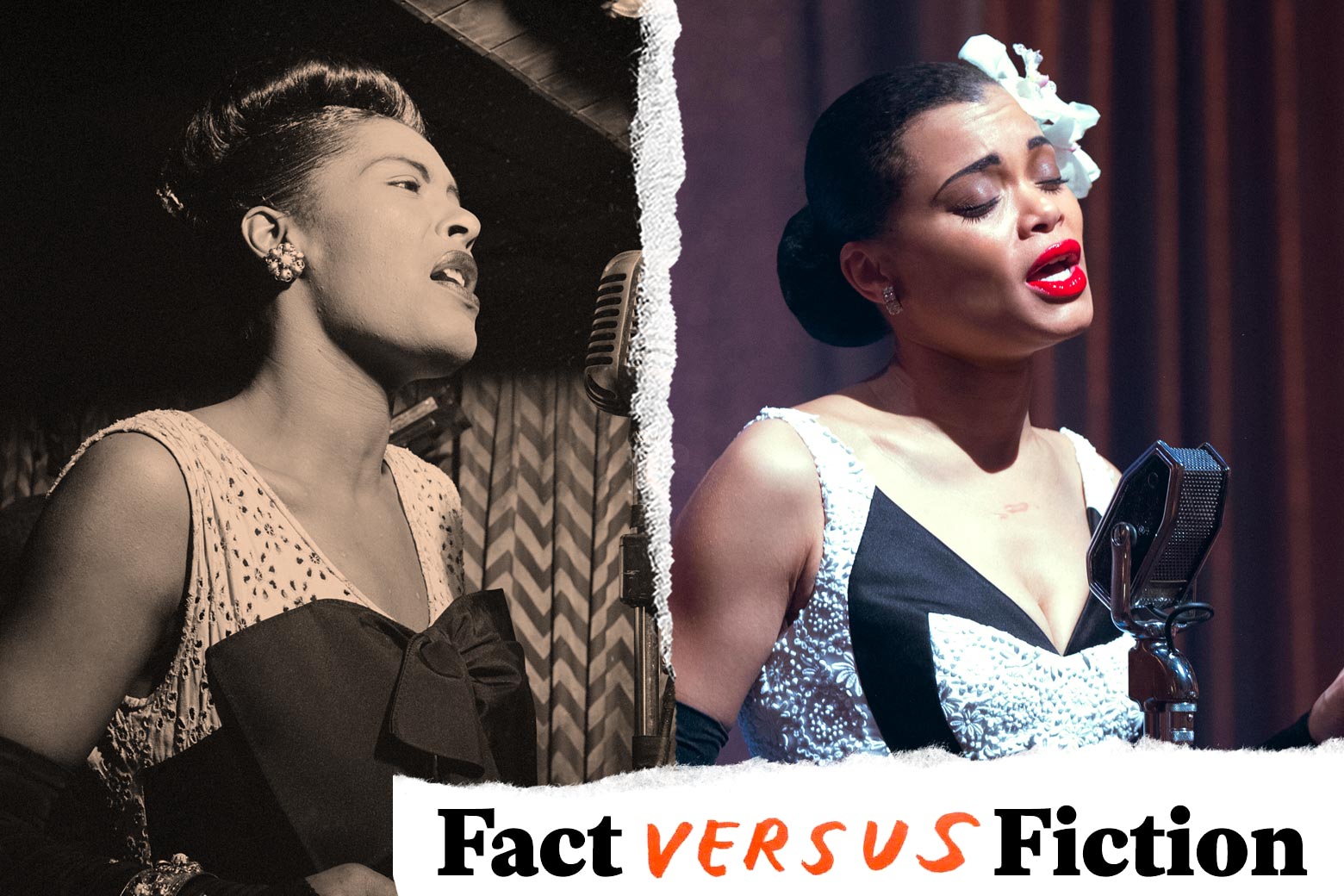

Director Lee Daniels told the Hollywood Reporter that The U.S. vs. Billie Holiday “isn’t a biopic,” and as longtime Canadian journalist Robert Fulford once wrote in the National Post, it is difficult for anyone to attempt to chronicle “an authoritative Life of Billie Holiday” anyway, because “the documents don’t exist, and the witnesses have often lied. … Billie herself would tell the same story several ways.” Still, there are chronicles of Holiday’s life from this period we can reference to figure out: How much of The U.S. vs. Billie Holiday is true to history?

“Strange Fruit”

The movie starts with a graphic photo of white people attacking a Black victim, with overlay text noting that in 1937, an anti-lynching bill was considered in the Senate, though it ultimately didn’t pass. This is true: A bill was introduced in the chamber early that year but was filibustered out of further consideration, although a version of the bill would be passed by the House in the spring. The same on-screen text also mentions that “Billie Holiday rose to fame in part due to her song ‘Strange Fruit,’ a lyrical, horrifying description of a lynching,” which is true to the record. 1937 was the year a teachers union journal published “Bitter Fruit,” a poem written by Jewish educator and anti-racist activist Abel Meeropol in protest of the continued lynching of Black Americans. It would later be set to music by Meeropol himself and was recorded by Billie Holiday in 1939 as “Strange Fruit.” By that time, Holiday had already spent years recording prolifically and working with prominent jazz bandleaders like Duke Ellington, Teddy Wilson, and Count Basie, but it’s accurate to say her nationwide recognition did increase significantly after the release of that record.

Café Society

Billie Holiday (Andra Day), accompanied by her stylist Miss Freddy (Miss Lawrence), sits down for an interview with radio journalist Reginald Lord Devine (Leslie Jordan). Neither of these two characters are real, though Daniels told Variety that Devine was based on “a fusion of Quentin Crisp and Skip E. Lowe.” Devine sets up a flashback to February 1947, when we see Holiday performing at New York City’s Café Society, the first racially integrated nightclub in the U.S. and the venue where Holiday had debuted “Strange Fruit” eight years prior. A voice-over from Devine mentions that a cast of important figures in Holiday’s life were all there that night, including singer and activist Lena Horne, actress Tallulah Bankhead, manager Joe Glaser (Dusan Dukic), and Holiday’s then-husband Jimmy Monroe (Erik LaRay Harvey). Also at the club that night is undercover federal agent Jimmy Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes). Very little is documented of Fletcher’s life in particular outside his legal entanglements with Holiday, so it is difficult to verify details about him.

Although these were indeed all major people in Holiday’s circle, Holiday was working for NYC’s Downbeat Jazz Club during this time, and Café Society had started experiencing financial troubles by then, so this particular scene with so many significant figures conveniently congregated is almost certainly an invention. There is, however, one curious part of the sequence that rings true to life: a mention of Orson Welles waiting at the club for Holiday. The two had a well-documented affair in the early ’40s.

In another scene at the café, we see Holiday with Monroe, Glaser, and legendary saxophonist Lester Young (Tyler James Williams), who in real life played with Holiday for years, earning from her the affectionate nickname “Prez” and giving her the lasting alias “Lady Day.” As jazz writer Steve Provizer points out, however, the film’s overall depiction of Young’s playing style and personality is inaccurate. The group is also seen reading a newspaper, which likely would not, as depicted, have spurred a bickering among them in 1947 regarding a quarter-page ad for Holiday singing “Strange Fruit” at the café, considering her then-ongoing Downbeat club engagement would have probably prevented her from holding such a performance in a different venue. Holiday and her team argue over the continued performances of “Strange Fruit” (whose writer was in fact a registered Communist Party member, as Glaser states), which to this day is suspected to be a major motivating factor for the federal hunt of Holiday.

Harry Anslinger’s War on Drugs

This newspaper does serve as an introduction to another major figure: Harry J. Anslinger (Garrett Hedlund), then head of the Treasury Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics and one of the primary leaders of the government’s effort to stifle Holiday. Despite President Harry Truman’s tepid steps toward advancing civil rights for Black Americans, racist Democrats still held a tight grip over his party—including Anslinger, who despised jazz and its icons.

Anslinger appears in a scene with other notorious historical figures: Reps. J. Parnell Thomas and John Rankin, Sen. Joe McCarthy, and McCarthy aide Roy Cohn, the latter two of whom had their own connections to and vendettas against the largely Black jazz scene. Holiday is then seen with trumpeter Joe Guy (Melvin Gregg), who had an affair with her and supplied her with drugs while struggling with addiction himself (although it should be noted that it was Holiday’s husband Jimmy Monroe who’d first supplied her with heroin in the early ’40s).

It is around this time that we see Fletcher start to court Holiday romantically, including by showing up at the funeral for her chihuahua Chiquita—who was in fact one of Billie’s beloved dogs, but who did not die in 1947. It is true that Fletcher was assigned by Anslinger to tail Holiday undercover, a job Fletcher took on because of his own hatred of drugs and their effect on Black Americans. We also see Holiday together with Tallulah Bankhead (Natasha Lyonne), after an implication that the two celebrities had had an affair together, which they famously did (Anslinger is later seen questioning Bankhead about her affair with Holiday as well as Holiday’s purported trysts with other female celebrities.)

The United States vs. Billie Holiday

According to Holiday herself, she really was forced off the stage after singing “Strange Fruit” at Philadelphia’s Earle Theater in May 1947, despite having received a rapturous welcome at first. The next scenes are somewhat fudged: The movie depicts Holiday at Joe Guy’s New York apartment the day after the performance, where she’s apprehended by a group of federal agents led by Jimmy Fletcher, who reveals his true allegiance to the government. Out of spite, Holiday strips naked and berates Fletcher. However, the raid took place in Philly itself, at the Attucks Hotel shortly after Billie’s performance at the Earle. And she did strip in front of Fletcher and his companions during her arrest—but in reality, she also pissed on the floor.

The case against Holiday begins at the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, with Judge James Cullen Grady presiding. According to Holiday’s autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, she was arraigned there on drug charges stemming from the hotel raid and sentenced to serve at least a year at the all-woman Alderson Federal Prison Camp in West Virginia. (It is worth mentioning, while citing the memoir, that its account is full of fabrications, though this in particular doesn’t appear to be one of them.) The courtroom scene implies that Glaser was responsible for setting Holiday up in this instance, which is true.

During this time, Fletcher is seen listening to more of Holiday’s music and taking a liking to it, which, as we’ve established, we can’t know, although Johann Hari noted in Chasing the Scream that Fletcher did come to regret his role in investigating Holiday. Two other scenes with Fletcher ring partly true to the historical record: Miss Freddy mentioning to him that Holiday was raped when she was 10, which is true, and Anslinger telling him that then–FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover thought “Strange Fruit” was an “un-American,” provocative song.

Billie’s Comeback

Holiday serves about a year at the prison before being let out early, by March 1948, for good behavior. After her release, her new manager Ed Fishman (Alain Goulem) wants to get her headlining Carnegie Hall. The effort goes through and the prestigious venue sells out, priming the path for Holiday’s comeback. While at the hall, someone yells for her to sing “Strange Fruit,” which she says she can’t do. However, Carnegie Hall’s own website mentions “Strange Fruit” in the setlist for Holiday’s March 27, 1948, concert.

After the successful show, Holiday runs up against more legal trouble: Because of her record, she can’t get back her cabaret card, which is required for her to perform in NYC jazz clubs (all true). However, she gets a hookup at the city’s Ebony Club, run by John Levy (Tone Bell), whose relationship with the police gets them off his back (and who is, incidentally, not the same John Levy who would accompany Holiday on bass at Carnegie Hall). She starts up a relationship with Levy for a while, which devolves into the club owner taking advantage of her, abusing her, and not paying her the money she’s owed. A later scene shows Levy planting drugs on Holiday and setting her up for another arrest by Fletcher and the feds; although an old Oakland Tribune article reports that Holiday and Levy were both arrested during the early-1949 raid, the setup does appear to have been coordinated by Levy.

Holiday managed to prove her innocence and was acquitted, though there’s no record I could find of Fletcher purposefully throwing the case on the witness stand to help her do so, as is shown on screen. The Ebony magazine cover displayed that shows a portrait of Billie with the cover line “I’m Cured for Good Now” was from the actual July 1949 issue, her declaration of her effort to stay away from heroin. She went back on tour that year and is seen performing in Baltimore, though as Steve Provizer mentions, it’s highly unlikely she would have crowd-surfed as seen on film, even had the concert gone as depicted. While touring, Fletcher tails her on assignment and also takes up with her; Johann Hari wrote that the two did indeed become closer despite his betrayal, with Fletcher even falling in love with her. Whether the two had such a long affair, however, is impossible to verify.

One scene in which Fletcher shoots up with Holiday and the band (undercover agents would often shoot up with their targets to demonstrate that they weren’t narcs) takes him into a view of Billie’s horrible childhood: We see her as a girl being referred to as “Eleanora” (her real name) and being dismissed by her mother, who indeed was often absent and later became a prostitute who forced young Holiday to also engage in sex work.

Holiday’s appearance with actor George Jessel (Joe Cobden) on his show The Comeback Story in 1953 was a real broadcast where she mentioned her marriage to Louis McKay (Rob Morgan), who would become her manager.

Holiday and McKay take off on an international tour and find continued success, including a report in Tan magazine and the recording of the acclaimed 1958 album Lady in Satin. But trouble arrives again when Holiday relapses. Lester Young dies, and his wife does not let Holiday sing at the funeral. McKay batters Billie so badly that sometimes she has to tape up her ribs before performing—not to mention, he attempts to wrest control of her estate and works with Anslinger to arrest Holiday for her drug use yet again. All of this is sadly true to Billie’s life.

Holiday’s Death and Legacy

Billie Holiday comes down with cirrhosis of the liver and is hospitalized. As is seen in the movie, the feds tailed her even while she was in this condition, planting drugs in her room and attempting to get her to name her dealer. She was handcuffed to her bed, and law enforcement kept a tight watch over her quarters, even as fans gathered outside the hospital to wish her well.

As the final text slides of the film say, Holiday died in the hospital on July 17, 1959, while still under watch by the narcs. McKay handled her burial arrangements. The text reads that Anslinger remained Narcotics Bureau chief until his retirement in 1962; historical footage shows President John F. Kennedy officially commending him for his government service. This is true to Anslinger’s biography. Meanwhile, “Strange Fruit” was indeed inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1978 and named song of the century by Time magazine in 1999. And the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act was taken up by Congress early last year, though it has yet to get through the Senate.