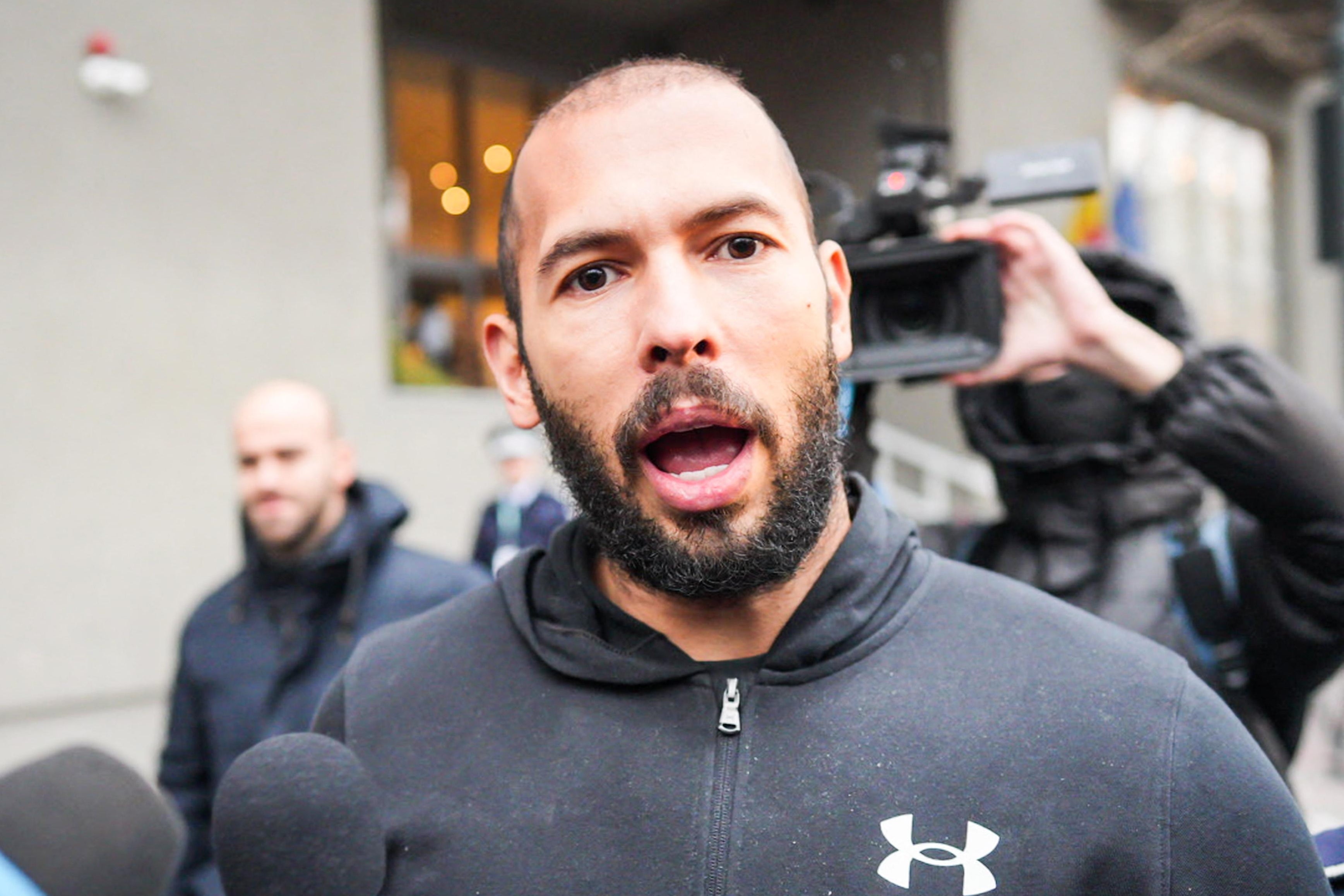

When Andrew Tate was indicted in Romania in June, no one who’d been paying attention to the drama surrounding him was particularly surprised. Tate and his brother Tristan were arrested in December on charges of human trafficking, forming an organized crime group, and rape. And Lisa Miller, who’d spent six weeks watching Tate’s content and immersing herself in his universe for a New York magazine story, saw the indictment coming.

There’s no one good phrase to describe Andrew Tate. He’s not just a podcaster, or a YouTuber, or former kickboxer, or a misogynist, or someone indicted for truly heinous crimes. He’s something else—some creature of the internet, a chimera that is equal parts hate, self-empowerment, and tremendous online savvy.

On a recent episode of What Next: TBD, I spoke with Miller about how Tate became that creature, and how his mindset infected a generation of teenage boys. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Lizzie O’Leary: Tate’s story more or less starts with kickboxing in the 2010s. He was living in the U.K. and fighting under the name King Cobra. But he desperately wanted to be rich, and kickboxing wasn’t going to help him with that. So, he capitalized on the one “asset” he had: his girlfriends. What did he do?

Lisa Miller: Tate said he had 75 women working for him doing webcam in four different locations in the U.K. and they were charging $4 a minute. The women told sob stories to their clients: “My grandmother’s dying” or “My dog needs to go to the vet” or “I can’t finish paying for college.” The clients would give them money, and Tate, who was sort of an online pimp, would take a cut. Something about that business model hit a chord with him—that’s when he moved to Romania and started this thing called Hustler’s University, which was sort of like a pyramid marketing scheme. He entices young men and boys to join; they pay $50 a month. They enter this world in which they can learn to do copywriting and other skills—but the main thing they learn how to do is to cut, shred, and repost content of Andrew Tate.

So, he basically has this whole army working for him.

They’re all working for him. And then he gets real smart, and he starts going on podcasts and longer-form interviews so that his army has more content to shred and repost. And that’s how he developed this viral moment; he had hundreds of thousands of men and boys who were consuming his content and reposting it—almost always on TikTok. Suddenly, if you are between the ages of 12 and 20 and you spoke English, Andrew Tate was dominating your For You page on TikTok.

Who are the kids who were suddenly finding themselves flooded with Tate content?

They’re everybody. It’s really tempting to think that Tate fans are not “our boys,” that they’re not nice boys from well-educated parents who have good values. But that is 100 percent not true. After my story ran, the number of emails I got from friends who have teenage boys who said, “I asked my son, ‘Have you ever heard of Andrew Tate?’ And he was like, ‘Of course. I watch him all the time.’ ” Yes, it’s everybody’s boys. You couldn’t contain this phenomenon.

Where were these kids seeing Tate? Because he was banned from Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok last year.

The explosion occurred initially in March or April 2022, before he was banned. By June, it was so big that it was uncontainable. The other thing that happened early last summer was that Tate was everywhere, and the Tate opponents and critics were also everywhere, and they only made Tate bigger. In August of last year, Andrew Tate was more Googled than Kim Kardashian and Donald Trump and the Queen of England combined. One of the things that is so interesting about Tate was that he was that huge and the parents didn’t know about him.

Because he’s not showing up on their social media?

If you’re over 30, you’re not seeing Tate. You’re only seeing Tate if you’re 12 to 24, unless you’re a martial arts fan or a chess fan or a Bugatti fan, unless you’re specifically in the worlds that he’s in. And then, yes, he was banned from all the platforms, but you can’t really weed TikTok, because Tate himself didn’t have that many followers. He had all of these stans who were reposting his content. You can weed an account that has Tate in the name, but if it doesn’t have Tate in the name, it proliferates to the point where it’s impossible to actually take it out by the roots.

What about Tate’s message was sticking with all these different kids?

I think it’s twofold. For a lot of the kids, TikTok was the entry. At first, they responded to his look, which was so exaggerated, so caricatured and hyperbolic. They thought he was hilarious; they thought he was a cartoon. He was saying all the stuff that you’re not supposed to say in liberal blue circles, and teenage boys just loved that—so that’s the entry point. But underneath that, if you look at Tate in long-form and not on TikTok, you see that what he’s offering is a kind of self-help. Go to the gym, work out, take responsibility for yourself, and step up and be a man. And I think that’s the center of the whole thing, that it’s OK to want to be a man in a traditional sense, which means, in Tate’s terms, to make money, have cars, have diamond watches, smoke cigars, have girlfriends, and to take steps to attain those things. That’s a message that is not popular or approved, and I think boys, especially straight boys, were like, “Oh, thank God. Thank God somebody is there who is telling me it’s OK to want to be hot and have a fast car and a pretty girlfriend.”

The boys could take the over-the-top stuff and wink and nudge it away. But they also heard video clips with titles like “Why Men Can Cheat, but Women Can’t” and “Women Must Cook, Clean, and Obey.”

He said things like: “Women are property.” “The intimate parts of women’s bodies belong to their men.” “They can’t drive.” “They are bad leaders.” “They are untrustworthy.” The boys tried to discount the misogyny by saying it was cartoonish, it was play, it was a joke—and what was good about Tate was this message to step up and be a man, work out, make money, be in charge of yourself, don’t whine, be disciplined, struggle is part of life … I think all of that was very appealing to them, and I think that was the mind trick that they were playing on themselves: If I can just compartmentalize all this misogyny and follow Tate, his steps to being a man, that will be OK.

What do you think the indictment in Romania does to Tate’s popularity? Does it matter?

When my story was published in the winter of this year, Tate was already in jail and his popularity was already dimming in its broad scope. He wasn’t on everybody’s For You pages anymore. The boys at school who used to say “Free Tate” weren’t saying that anymore. It just wasn’t quite so present by the winter. But I do think that the hardcore stans have doubled down. Tate has a presence on alternative social media platforms, and those people are just much more hardcore. Do I think that it’s possible that some of those people can be radicalized? Yes, I think it is. The hardcore stans are much closer to what we think about as incels or red-pill people than the broader phenomenon. Those people are still there and still with Tate. And I think that his charges and upcoming trial will only solidify their commitment to him.

For the majority of his adolescent audience, do you think Tate will be a phase, a thing they look back on in a few years and cringe at?

I think kids are flexible and resilient, and a lot of the kids I spoke to see their own hypocrisies. Even though they try to do this brain thing of “Misogyny is bad, but Andrew Tate is funny and good,” they’re also able to say, “I don’t want to be that kind of guy.” And they’re able to talk about that too.

When you’re a teenager, you do stupid and dangerous things, but it doesn’t mean you turn out to be a horrible person—which is not to let anybody off the hook, because I really do think there is a pathway to radicalization that is real and dangerous. But I also think it’s not universal, it’s not inevitable, it’s not irreversible.

Could Andrew Tate have existed without the internet?

No. No way. I mean, his genius was the virality. That was what made him such a phenomenon, the way he exploded almost overnight within this huge group of people, but not for anybody else. That is a purely internet phenomenon. And he understood what he was doing, and he cultivated that and promoted it very strategically, both by curating his look and by planting these extremely misogynistic, viral quotes in his interviews. It was all very conscious.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.