This is where I should be recounting my dreams. Surrealism, we are told, comes from dreams, though that explanation is oversimplified and, in some aspects, just wrong. Dreams are themselves results, and both dreams and Surrealism come from the same root cause, the unfettered function of the unconscious mind; the important difference being that Surrealism makes choices, and dreams are unconscious in every sense of the word.

I’ll spare you my dreams. Surrealism is more interesting.

Surrealism in film began at the beginning, before Breton or Dalí, before Surrealism began as a movement or gained a capital letter. Filmmakers were always juxtaposing objects in strange ways, whether it was the live-action “trick films” of Georges Melies or the films of French animator Emile Cohl in the early years of the 20th Century. Like comic strips, which were born only slightly earlier, animated cartoons cast the viewer into another, more mutable, world. Characters and settings could (d)evolve before your eyes. As if animators inverted Sol LeWitt’s saying, “Obviously, a drawing of a person is not a real person, but a drawing of a line is a real line,” they realized that nothing need stay the way it is. A line is a line is a line, so the line that formed a dog could change into a pretty woman leaning out a window and back to a dog, much to the distress of Koko the Clown, who was puckered up for a kiss (Koko the Kop, Fleischer Studios, 1927). Felix the Cat could detach his tail from his body and use it as a cane, an umbrella or a weapon. The line became an actor playing any role required, sometimes multiple parts per film. All that was missing was Surrealist intent; for all the Surrealists interest in the unconscious, animated cartoons became surreal with no forethought. Film made the inanimate animate.

Animation and surrealism went hand-in-hand from the start, buoyed by the giddy realization that lines could be made to do anything – a drawing of a person could be a real person, with expression and emotion just like anyone. Winsor McCay’s comic strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend exemplified cartoon surreality back in 1904, when it first began. McCay’s nightmarish fantasies were cinematic from the start – perhaps the most famous being the strip of February 25, 1905, which shows the death and burial of a man from the corpse’s point of view. Edwin S. Porter directed a live-action Dream of the Rarebit Fiend film for Edison in 1906; McCay, one of the pioneers and geniuses of the animated film, made three fairly tame Rarebit Fiend animated shorts in 1921.

With the coming of sound, surrealism – best rendered with a small s – began to fade from animated film, enduring longest at the New York-based animation studios: the Fleischer Studio, the Van Beuren Studio and, to a lesser extent, Terrytoons. West Coast studios more closely followed the bucolic visions of Walt Disney, a Midwesterner with an eye toward more traditional forms of storytelling. The Disney paradigm of animation as “the illusion of life” came to dominate the field, along with a more family-oriented, even parochial, approach. In New York City, however, things were more raucous, generally less talented (the good people went West with dismaying regularity) and both ahead of and behind the times.

Cartoon surrealism was bound to die as the Great Depression clamped a new outlook on the country. Consider incidents from Bimbo’s Initiation, a 1931 Fleischer cartoon that exemplifies many of the what-the-hell qualities of New York surrealism. Bimbo, a dog and sometime star of Fleischer cartoons, is hazed by a mysterious order of round-headed people wearing candles on their heads – friends of Dali’s, no doubt. His steadfast refusal to join them puts him in jeopardy: a sword blade projects from the wall and, as Bimbo fruitlessly tries to evade it (the floor moves under his feet to keep him close) the blade grows eyes and begins to lick its lips in anticipation. No violence ensues, but the air of a fever dream hangs over everything. Later, Bimbo tries to escape on a stationary bike beside a pool of water. He eventually gets the bike moving, circles the pool (with, and then without the bike), and falls into the water. When he hits there is a sharp crack, like breaking glass and the surface of the pool becomes hard and solid. Betty Boop appears through a door, and gestures to him. “Come inside, big boy,” she says and Bimbo, being no fool, follows.

Surreal gags did not necessarily have to make sense, provided they filled up the reel and, with luck, got a laugh. What was it made director Mannie Davis and storyman John Foster include a skeleton in a fireman’s hat, driving a chariot in his cartoon Gypped in Egypt (co-directed with Foster, Van Beuren, 1930) and again in King Tut’s Tomb (Terrytoons, 1950)? Nothing says Egypt like undead firemen. The first time was a nightmare at a time when Surrealism was making headway into museums across the world; the latter an echo of a faded style. The free-for-all humor and subjective reality gave way to more staid, safe stories. Dreams became episodes, not films unto themselves. Van Beuren shut its doors in 1936, the Fleischer Studio was taken over by Paramount Pictures in 1942, and Terrytoons remained, a slightly antique reminder of days gone by, into the 1960s. The Disney model overwhelmed all, aided by the Production Code, adopted in 1930, and the simple magic of line went dormant.

I cited the examples above because this hallucinatory sort of story is unique to the New York-based studios, and recurs as people move from one to the other. It is a subgenre of Surrealism that, despite the technical limitations of many examples – Van Beuren’s animators were about the worst in the business – deserves consideration. The Surrealist artists produced only a few films, making the animated surrealism the dominant form for quantity in the period. Animated films are often overlooked in so-called serious studies of art, because of the commercial element, the absence of auteur theory in the studio machinery. This is a misunderstanding about what makes art itself, a misunderstanding that is often applied to illustration. Heaven forbid that money should change hands – at least, prior to Andy Warhol. He rewrote the rules. Pity he never ventured into animation.

We tie ourselves too closely to reality, which runs the risk of all turning all our expressions into reiteration. Disney did admirable things with realism, justifiably deserving their dominant position in animation history, but it runs the risk of negating the need for animation in the first place. That’s the appeal of Surrealism; it’s a jigsaw puzzle that fits together in more than one way. Animated cartoons from the mid-30s and earlier have a freewheeling creativity that as often as not sabotages the film in the limited Hollywood sense of storytelling. I am referring mostly to those made by the major film studios. The exceptions come later.

A movie theater might be the best venue in which to experience Surrealism. The dark is both womb-like and menacing, the people friends and strangers. Sounds intrude on our senses: the crunch of popcorn from someone behind you, a dull roar of the action movie in the next theater seeping through the thin walls of the multiplex. Animation is the best form for Surrealist film, and the least appreciated. It took many years before animation studios had skilled animators who could have handled the hyperrealism of Salvador Dali, who had quickly become the archetypal Surrealist. Winsor McCay could have done it, but McCay’s career was in decline by the time Surrealism became a movement. The actors are truly at the mercy of the filmmaker; the settings can take any shape desired. This brings us to the Disney/Dali collaboration Destino.

Disney was not always the 800-pound gorilla in the field. There were many lean years at the Disney studio. Classic films like Pinocchio (1940) Bambi and Fantasia were not financial successes in their first run. By controlling costs, and cleaving firmly to the middle of the road, Walt was able to survive the rough years and gain an ever-firmer foothold on the path to success. What Disney had was that very “illusion of life” paradigm that suited Salvador Dalí’s lush pictorialism. Transformation, that so suited animated surrealism before, was more free-form; Dali and Disney both worked their art over carefully. Precision made them fit together. MGM and Warner Brothers had animators capable of such projects, but they were not interested in animated features or Surrealism. Dali was already established as the foremost Surrealist artist to work in film, and the allure (and money) of Hollywood had already drawn him in, most notably in his work with Alfred Hitchcock in Spellbound (1945). In 1946 he agreed to work with Disney artists to create a short subject for an upcoming film. They chose a song, Destino, by Mexican songwriter Armando Domínguez. A Disney animator named John Hench was assigned to assist Dali. After working two sessions in the Spring and Summer of 1946 the project was shelved, probably for financial reasons, though no definite reason has ever been spelled out. According to some accounts about 15 seconds of test footage was produced, of two tortoises with oversize, distorted human heads; this scene survives in the completed film, but not in this footage. Dali’s preparatory sketches and paintings went into the archives, along with typed scenarios and notes.

Now dream a while – 50 years at least. Not real dreams, but the waking dream we call history. Dream that a Cold War rose and fell; dream that a wave of modernistic design swept through the animation field and passed. Dream many things, and dance if you can, for time and dreams and dances are at the heart of Destino. At last, the project was revived. John Hench, though over 90 years old, came out of retirement to work on it again. The original proposal had called for a cartoon bracketed by live-actions prologue and epilogue featuring Dali, as an episode in a multistory feature such as Disney’s Make Mine Music (1946). Destino was animated by a French crew of Disney animators, as Disney’s American crew was at low ebb. It rightly won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short for 2003. The completed version is shorter, a standard 7-minute short subject, its story truncated and completed by John Hench, who deserves co-creator credit.

The catalog essay on Destino in the Tate Gallery’s book Dali & Film (2007), by Fèlix Fanés, does not allow direct comparison, as he shows no signs of having seen the finished film. Cuts and changes to accommodate the shorter length have tightened and simplified the story. Elements that repeat in the scenario, such as a group of large green eyeballs and telephones, now only appear once. Some of Fanés’s descriptions, taken from the scenarios but apparently not directly quoted, are baffling: “Two white gazelles appear as the avalanche of love leads to the crystallization of the human notion of happiness, which then shatters to reveal love as a cosmic phenomenon.” I don’t know if the film is better for having lost that scene or not.

Destino is a Surrealist ballet about searching for love and, ultimately, coming close to it, perhaps even finding it. How appropriate, now that Surrealism is itself a memory, that an air of tristesse should permeate the film. The lovers, who never touch or speak, are alone yet not alone, wrapped in the search for each other. The landscape changes to keep them apart, though in the original scenario they had a pas de deux late in the film. The song, translated into English by Ray Gilbert as “My Destiny of Love,” is sung solo and then by a chorus that is a flashback to classic Disney choral arrangements. The lyrics are unimportant.

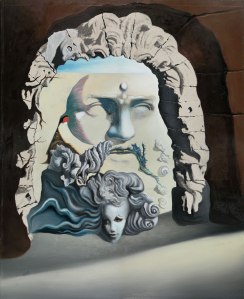

The woman appears out of nowhere, and has affinity with the shadow of a bell tower, to the point of wearing the bell’s shadow as her dress after she loses hers. The man begins and ends carved in stone on the face of a pyramid with a watch-face beside him, and a medusa-head fountain. Most descriptions of the film refer to him as “Chronos.” The backgrounds are scrupulously copied from Dali’s studies. As animation fit well into Dali’s vision, allowing him to add movement through time – often implied in his work – so too did his use of landscape conform to the needs of animation. Indeed, many of Dali’s paintings look like cartoon layouts, with broad open spaces so that the characters “read” well, and landscapes that contribute little to the story. They are neutral, safe spaces, with little of the unease found in a de Chirico or the dream-like quality of a Paul Delvaux. The catalog, without making this point specifically, provides ample evidence, reproducing paintings such as Shades of Night Descending (1932, Salvador Dali Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida) or the famous Persistence of Memory (1931, Museum of Modern Art, New York) that could be background paintings for Destino. Dali’s familiar tropes abound: melting watches, ants that morph into bicyclists, each wearing a loaf of bread upon his head. The ants, having made their screen debut in Dali and Luis Bunuel’s Surrealist classic, Un Chien andalou (1929), are greeted like a favorite character actor returning to the screen. Midway through the transformation the bike wheels look like clocks, the cyclists stylized glyphs; that looks both back and forward, coincidentally reminding me of the animated titles to Around the World in 80 Days (1956), designed by Saul Bass and others, where Phileas Fogg is represented as a watch face with legs and a top hat.

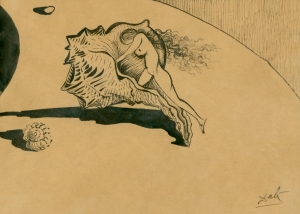

The dancer also changes form, her head becoming a dandelion, scattering seeds through the air. She also spends time in the buff, but more briefly than her male counterpart. The nudity is very discreet by today’s standards, and inoffensive; it might have looked daring, though, packaged with something of the period, such as “The Whale Who Wanted to sing at the Met.”. The tortoises form the woman’s body in their negative space as a simplified white shape, like the dandelion seeds, with a ball for a head. She dances about and throws her head to Chronos, now a baseball player, who hits it – hardly the way to treat a lady. The ball becomes a large, roughly heart-shaped pillow, which the man (naked again) presses to his chest until it shrinks down and enters his heart. At the end he is a statue again, with a hole in his chest (a bird had been carved there before) through which we can see the bell tower. So we are left with the sweet voices of the chorus, and a landscape without life that speaks of love. Though the whole effect is nostalgic, it captures Dali’s brand of Surrealism better than any other cartoon. It’s a shame we had to wait half a century, while the world danced away with Surrealism tucked in one forgotten corner of its heart. Dali’s prologue and epilogue, in which he was to have explained his distinctive imagery, would have been redundant, but by Destino’s very inclusion in a Disney picture, Surrealism was tacitly accepted into mainstream culture.

Animation has not stood still in the intervening years. Styles have come and gone, and computers supplanted hand-drawn animation. Destino incorporates both traditional and modern elements; backgrounds are sometimes computer-generated, while the figures are hand-drawn. The main piece of foreground computer animation is the tortoise sequence mentioned before, and I am uncertain whether it is all CG or only computer-assisted. The juxtaposition of old and new works well. The figures have been slightly updated, made to conform to a more 21st Century idea of beauty. Their animation has also been simplified, rendered more graphic, with fewer half-tones or airbrushing in the shadows than you would expect from classic Disney animation. This simplification, probably drawn from anime, at times extends to the movement of the figures. Instead of smoothly animated motion, there are times when a figure will dissolve from pose to pose, a trick that is inconsistent with the classic Disney-style elements. I can’t imagine Walt approving of it.

Destino, while beautiful, has the sad air of a forgotten childhood toy rediscovered. Reality has become the nightmare; playing with dreams is the stuff of the New Age section of a bookstore. As Dali was repeating his classic riffs in Destino, marking the summation of a movement diminished by time, so did Destino make no headway or new ground in animation. It’s a fine film, worth repeated viewings. Like an old friend, it is welcomed and embraced with, just beneath the surface, a slight undercurrent of amicable boredom.

Continue to part two.

Pingback: Destino and animated surrealism pt. 2 | Art Matters

Pingback: Foundation 3D – Aesthetics Genre Studies – Art Trainee Journal

Pingback: A Mixed Salad | Art Matters