On June 13, in Milan, the statue dedicated to Italian journalist Indro Montanelli was smeared by red paint and marked with the writings “rapist, racist”.

This is the second time that activists smear the statue of Montanelli: the first time, in 2019, they covered it in pink paint during a women’s demonstration on March 8th. The action was claimed by Non Una di Meno, the Italian branch of the Ni Una Menos feminist movement. This last action was claimed by two different student activist groups (Milan Student’s network and Lume collective) and was completed between the evening of June 13th and the morning of the 14th.

Following the Black Lives Matter movement and the throwing of Edward Colston’s statue into the river in Bristol, UK, the statue of Montanelli had become a matter of discussion in the Italian mainstream media and social media in previous days. The reason, activists say, is that the monument erected by Milan’s municipality just a few years after the journalist’s death, deserves to be removed.

Indro Montanelli died in Milan in 2001 at the age of 92, after a life of immense success and fame. He was considered “the prince of journalism” and had been one of the most powerful voices in the Italian media for most of his life, even though his career started in a way that embarrassed some of his liberal admirers. He was indeed a keen supporter of Mussolini, and wrote in several magazines and newspapers of the fascist regime.

He was particularly vocal regarding the 1935 Italian colonial aggression against Ethiopia (Abyssinia at the time), an aggression he participated in with enthusiasm. One of his articles in the magazine Civiltà fascista (Fascist Civilization), recommended the soldiers to avoid any pity and human feelings towards Ethiopians. “White man must command”, he wrote.

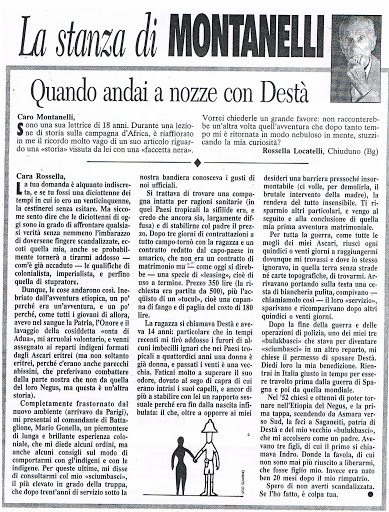

While in Abyssinia, Montanelli bought and married a 12 year old child who he kept as his enslaved wife. More than once, he explained his actions in interviews and writings, always bragging about it and showing no regret. The last mention of the child he enslaved for his sexual pleasure dates as recently as 2000, just one year before his death. In a public letter in response to a 18 year old girl asking about his famous Ethiopian “love story”, Montanelli called her “my little animal” and described the atrocious details of her rape. In 1969, Italian journalist and activist Elvira Banotti challenged Montanelli on the topic during a TV interview, and then Montanelli finally admitted that what he had done in Ethiopia, would have been considered rape in Europe.

The letter where the “great journalist” details the rape of his enslaved 12 year old child in 2000, just one year before he died.

Italy conducted the war against Ethiopia with genocidal intent. It is estimated that about 275.000 Ethiopian soldiers and civilians were killed by the Italian army, while Italy’s death toll counted around 4.300. Mussolini and his commanders on the ground (particularly General Badoglio, who later signed the armistice with the Allies) ordered a systematic use of chemical weapons against the Ethiopian army and population, and violated the Geneva Convention in many other ways.

For decades Montanelli denied the Italian war crimes in Ethiopia, even after they were proved in well documented studies by historians such as Angelo Del Boca. It was only after the Italian government admitted the use of chemical weapons against Ethiopians in 1996 – 60 years after the events occurred – that Montanelli recognized he was wrong in believing it didn’t happen. Until then, he had been the most important creators of one of the lies that has been polluting Italian historical memory and debate: the myth of Italians as good people, whose colonial aggressions were conducted with kindness and humanity.

The US State Deptartment prevented African American supporting Ethiopia from traveling to the front to take part in its war with fascist Italy. But a few did, including renowned aviator John C. Robinson, who took charge of Ethiopia’s fledgling Air Force. Source: https://t.co/qdczDOC3g2?amp=1

Although he was a supporter of the most violent expressions of the fascist regime, after WWII he became a revisionist, and in his many and widely read books about that era, he erased the ferocity of fascism and depicted Mussolini as a good man who, in the end, was fooled by his hierarchs. Montanelli managed to pass his revisioned narrative by claiming an objective point of view stemming from his opposition to Mussolini’s politics. An opposition he paid with imprisonment. However, Montanelli was briefly incarcerated just before Mussolini’s fall because the Duce considered him a “fascism profiteer” and not at all a political opponent. In reality, as we wrote above, he was a vibrant fascist.

During the Italian Civil War (1943-45) that followed the fall of Mussolini, Montanelli faked his participation in the Resistance and, with the help of his friend, the gestapo commander Theodor Saevecke, also known as the executioner of Piazzale Loreto, he flew to Switzerland. When in charge of the gestapo in Milan, Saevecke ordered the deportation of 700 Jewish people and the execution of many partisans, among whom were 15 men who were killed and exposed in Piazzale Loreto. In 1999, Saevecke was finally put on trial in Italy, and Montanelli testified in his favor. “I don’t give a fuck of their noises”, Montanelli said when he faced the screams and insults of the victims’ families.

The executioner of Piazzale Loreto was not the only nazi slaughterer Montanelli supported. Even the infamous Erik Priebke, who ordered the massacre of 335 Italian soldiers and civilians at the Fosse Ardeatine in Rome, received a letter of solidarity from him.

Like others who had joined Italian fascism, after WWII, Montanelli committed body and soul to the war against Communism, a war that provided for many war criminals a way to come back to action and allowed for their crimes to be forgiven? with the help of a new ally, the USA. While the American government pushed for a radical right wing turn in Italian politics, in a series of letters and meetings with the American embassy, Montanelli suggested the creation of a force made of 100.000 beaters of clear anti-communist faith. They should have been chosen among former fascists, army officials, businessmen and mobsters, who, though a terrorist strategy, would lead a law and order golpe. The near future that Montanelli wished for his country was a civil war that would have destroyed the Italian Communist Party and brought to power a Pinochet-like regime.

His ideas were actually put in place during the strategy of tension following which the neofascists and the secret services organized a series of terrorist attacks in order to stop the rise of the PCI to government. Montanelli took part in the events by decoying the investigation that followed the massacre of Piazza Fontana, when a bomb placed by neo-fascist inside a bank in Milan killed 17 people. The anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli was wrongfully accused for the attacked and died following a “fall” from the window of the police headquarters where he had been illegally detained for 3 days.

That is not all, the “great journalist” also used his media power to protect the business interests which caused the Vajont dam disaster which killed between 1,900 and 2,500 people in 1963.

Obviously, Montanelli was also a fierce opponent of the civil rights movement in the USA, because, he affirmed, the white race had to be protected.

With all this in mind, it is perhaps no surprise that Montanelli became a target of the Red Brigades, who kneecapped him in 1977, in the very spot where his statue was built to honor him as “the father of Italian journalism” and a red terrorism victim. After the protest from the anti-racist activists, the entire mainstream journalism world and most of the political spectrum emerged as one man in defense of his legacy and memory. Among them, the centre-left Mayor of Milan Giuseppe Sala stood out with a particularly disturbing statement: “everybody makes mistakes and we should all watch our own lives”.

The statue has been rapidly cleaned and is now guarded night and day by law enforcement members. But nevertheless, never in all these years Indro Montanelli’s crimes were so widely discussed in the Italian media. Like elsewhere, in Italy new generations look a lot less willing than before to forgive the “mistakes” of important men.