Let There Be Graphics

1981 image of Roberta and Ken Williams, founders of On-Line Systems, later known as Sierra

Despite the success of Infocom and their well-written interactive fictions like Zork, the plain text canvas of early computer adventures isn’t the summit of the rising video game industry. In 1979, Roberta Williams is a housewife with two kids, living in Simi Valley, California. Her husband Ken is a programmer at Informatics in Los Angeles, working remotely on large mainframe computers located thousands of miles away. Curious, Roberta tries taking a whack at being a trainee programmer, but finds she isn’t really into it, or if she even likes computers. Programming an income tax program at his home on a terminal hooked up to the computer at work, one evening Ken uncovers Microsoft’s version of Crowther and Woods’ Adventure aka Colossal Cave game sitting resident on the large mainframe and, after some experimenting with the verb/noun adventure game parser, shows it to Roberta. An avid reader, she forgets her trepidations with the computer and gets instantly hooked on the added dimension of actively participating in the adventure story, obsessively playing the game on Ken’s terminal via a 110 baud modem and teletype printer all the way to its conclusion.

Click button to play a version of the original Colossal Cave Adventure, on MS-DOS

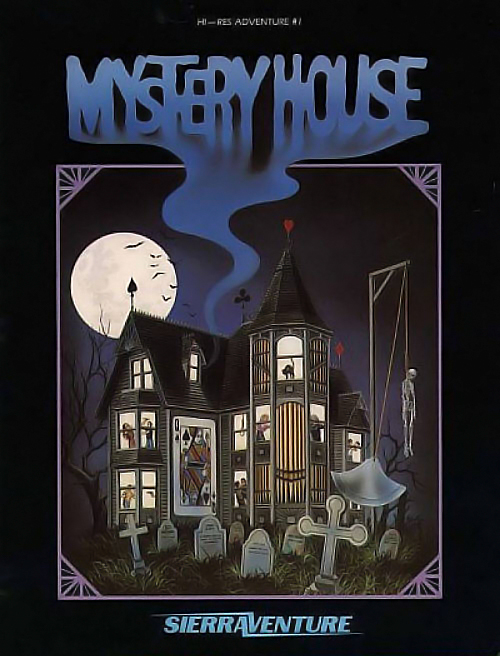

Upon learning that Scott and Alexis Adams, another computer gaming couple, have formed Adventure International in Florida and created several new Adventure-type games, Ken borrows a TRS-80 home computer from work and he and Roberta run through the Adams adventure game library. Varying little from Crowther and Woods’ original Adventure, with the same verb-noun parser and plain text screens, Roberta quickly tires of the format. Ken eventually purchases an Apple II computer in 1980, with the intention of creating a FORTRAN language compiler for the machine and selling it to Apple. Looking for a real challenge, and with the belief that she’s not the only person out there who wants to play more of these games, Roberta sets up shop on their rickety kitchen table and writes her own adventure for Ken to program on the computer, and they decide to try something completely new by adding images to go along with the text prompts. Mystery House, on 48K diskette for the Apple II, becomes the first computer adventure game to combine text with graphics. In a tale inspired by Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, as well as Parker Brothers’ mystery board game Clue, the player must roam a house finding treasure and avoiding the deadly fates of the other occupants. User input is a limited verb-noun parser with a vocabulary of a paltry 300-400 words… well below the over 600-word library available in Infocom adventure games like Zork. However, Mystery House does contain 70 images, rough outlines created by Roberta on a VersaWriter tablet using a metal arm with an electronic eye at the tip. With this arm, an image drawn on paper can be traced, and Ken writes a program to convert the drawings into plotting commands that the computer will execute, drawing the illustrations live while the game plays without having to take up the memory space of storing and displaying pre-drawn images. Even a type of rudimentary animation is present in Mystery House; when the player affects the drawn scene, by opening a door for instance, the program will redraw the image to display the change. Ken also invents a special language to create the game, for use only in making graphic adventure games, called the Sierra Creative Interpreter. SCI takes the same route as competitor Infocom’s ZIL; it is a platform-agnostic language that can be easily adapted to any computer.

Click button to play the first graphic adventure game, Mystery House, on the Apple II

They launch their new company, On-Line Systems, along with Mystery House and two other programs called Skeetshoot and Trapshoot, with an ad in the pages of the May 1980 issue of Micro magazine. Despite the rudimentary artwork, the couple consider their products “interactive films”, and while this might seen a grandiose description, Mystery House IS a sensation upon release. Priced at $24.95, the Williams sell 11,000 copies of the game inside the first year, grossing nearly 300,000 dollars for the new company. It is a small step towards one of Ken Williams’ goal for his nascent company: to be bigger than Activision. In 1988, Sierra On-Line releases their first graphic adventure game into the public domain.

On a Quest

In 1980, Ken Williams is worried about the rise in crime he senses in LA as he commutes back and forth to work. To find more bucolic surroundings to raise their two young boys, the Williams family pick up stakes and move from the LA area to Coarsegold, CA.; a brief 40 minute or so ride north from there and you’re into Yosemite National Park. With their Mom & Pop software company expanding, On-Line Systems spreads to their den and spare bedroom, and eventually to a space above the local print shop and then to several office buildings around Coarsegold. They produce 20 more games for the Apple II, including further Hi-Res adventures Mission Asteroid, based on SF novel Lucifer’s Hammer, by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. The first colour adventure game, The Wizard and the Princess comes from Roberta’s love of fairy tales, and is one of the first commercial entertainment programs available for the IBM PC, with the title Adventure in Serenia, when the mainframe giant’s first foray into home computers is released in in 1981. The Wizard and the Princess is also considered a sort of unofficial start of Roberta’s vaunted King’s Quest series (see below). Following up is Ulysses and the Golden Fleece, taken from Greek mythology. Produced by Roberta over a span of six months, Sierra also releases Time Zone in 1982, sporting over 1300 colour images and packed onto both sides of an astounding six floppies. Referred to in ad copy as a “micro-epic”, the game is a response to the feeling of disappointment Roberta always experiences at having a well-made adventure game come to an end: the length of Time Zone ensures that players won’t get that feeling of finality any time soon. That same year, the company name is changed to Sierra On-Line. They also post revenue of around $10 million, placing them as a top-tier independent game publisher.

While enjoying the success that being a game publisher has brought, Ken Williams is feeling a bit taken aback that the company he helped found has moved away from his original vision of a “serious” business applications maker. Some feedback that reassures him that his company is on the right track comes in the form of a heartfelt letter in 1981 from one of his heroes: Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, who writes in thanking Sierra for making compelling adventure games that brought him great joy while convalescing for 5-weeks after a serious crash of a plane he was piloting. Sierra does put their hands into productivity applications as well as games, with word processor Screenwriter and Screenwriter II in 1982, and personal filing system The General Manager in 1983. Sierra On-Line is also lined up as a 3rd party developer of software for Coleco’s highly-anticipated ADAM computer system, to port their HI-RES graphic adventures like Ulysses and the Golden Fleece and Cranston Manor to that platform. In 1984, the company officially drops the “On-Line” from their name, now known simply as Sierra. To ease the process of programming the company’s contributions to the gaming landscape, two graphics utilities, called Paddle Graphics and Tablet Graphics, are developed to automate the illustrations in the games.

Game of Thrones

In 1983, Sierra is visited by a crew from IBM’s home computer division in Boca Raton, Florida. They are hoping the company can produce a game to show off the advanced graphical and memory capabilities of a new computer they are skewing towards the gaming market, then known only by its codename: Peanut. So feared is the idea of IBM entering the low-end computer market, that Apple’s stock price is halved overnight just on the rumour of such a machine. Using a provided prototype system, along with IBM development funding AND the promise of game royalties, Roberta designs the next evolution of the graphical adventure. With Williams writing the story, artists then illustrate the scenes which are traced on a Calcomp Graphics Tablet. Programed using Sierra’s AGI (Adventure Game Interpreter) system, the result is an animated adventure game with astounding 16-colour pseudo-3D graphics, allowing the player’s onscreen alter-ego to walk in and around 80 different locations. The process is actually similar to that of the original Mystery House: the tablet merely gives the computer the instructions of what to draw, which it does in real-time as the player moves to different “rooms” in the game. The computer takes about four seconds to draw and colour each scene, although the drawing process itself is strangely compelling to behold: it’s like watching a small child with extraordinarily fast fingers completing a fantasy-themed colouring book.

Click to play the game that helped put graphic adventure games on the map: King’s Quest, on MS-DOS

With a team of seven programmers and artists and a development cost of $700,000, King’s Quest is released in 1983, weighing in at 128K and sold initially for what is now known as the IBM PCjr. Players control Sir Graham, who is charged by King Edward to search the kingdom of Daventry for three treasures. The PCjr ends up tanking in spectacular fashion, felled mostly because of its atrocious keyboard: wireless, but with rubber chiclet-style keys that make using it a chore. An update to the computer in the later part of 1984 fixes the keyboard problem, but the damage has been done. IBM only manages to move about 300,000 units all told, and mercifully puts Jr to sleep by ending production in April of 1985. This failure of the platform for Sierra’s biggest game almost puts the sword to the company… but Radio Shack valiantly rides in with a knight in shining armour, namely their Tandy 1000 computer. It is a 100-percent PC compatible, with much better expandability and a keyboard that doesn’t make you want to jump off a cliff. More importantly, it supports the PCjr’s advanced graphics system, so it can play King’s Quest in all its animated, 16-colour glory. The wild success of the 1000 and the fact that Sierra’s game is now on shelves in Radio Shack stores all over the U.S. means a big hit for Ken and Roberta too. Ported to other popular systems like the TRS-80, Apple II family and the IBM PC, King’s Quest sells over 2.7 million copies. It receives a subtitle, Quest for the Crown, when it undergoes a VGA graphical remake in 1990. The subtitle puts it in line with the seven sequels that follow it.

Click button to play King’s Quest II on MS-DOS

The first such sequel is 1985’s King’s Quest II: Romancing the Throne, starting a habit in the series of play-on-words subtitles, this one referencing the popular 1984 adventure film Romancing the Stone. The game is designed by Roberta Williams, with a story by Annette Childs. It finds Graham, now King of Daventry, questing to find and rescue (and betroth) a beautiful maiden from the far-off kingdom of Kolyma, secreted away by the jealous crone Hagatha. To enter the enchanted realm where the prisoner is kept, King Graham must scour the land for three magic keys. To create this wondrous world, Roberta sketches out each area of the game, to give the artistic team a guide of how the various places should look. She also plans out all of the dialog and game messages that are delivered to players, and what their available responses can be. Finally, she consults with the music composer to ensure that aural accompaniment matches her vision. When the whole shebang goes to the programming step, Roberta oversees things so the results comes out as expected.

Taking a darker turn, with a focus on magic, is King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human, released in 1986. With another story by Annette Childs, soon-to-be Leisure Suit Larry creator Al Lowe (see below) cuts his teeth in programming the game designed by Williams. The plot concerns Gwydion, slave to an evil magician who must escape before his 18th birthday or meet the awful fates of the previous slaves. Along the way Gwydion must also uncover the nature of his heritage, and via this truth rescue Princess Rosella. King’s Quest III also serves as a pretty good typing tutor: players must gather the ingredients for some pretty complex magical spells, then consult the game manual and type in multiple instructions for creating them, in full, utilizing the text parser. This process also serves as copy-protection for the game.

1988 sees the release of King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella, the subtitle a play on the name of the famous 1914 movie serial The Perils of Pauline. The Plot in this one puts Princess Rosella, introduced in the previous game, on a series of quests to retrieve a magical fruit that will save her dying father, King Graham. There are around 95 rooms or scenes for the gamer to adventure across, over a 24hr narrative within the game with a day and night cycle, and multiple endings possible depending on player actions. Over 11 man years are poured into the game’s development by a team consisting of over 13 members including programmers, artists and other creatives. King’s Quest IV features a number of developmental advances for the series, including a move to the SCI (Sierra Creative Interpreter) programming system, allowing for improvements such as more and better animation than the previous AGI… but also requiring users to upgrade their hardware to play it, and subsequent Sierra adventures. To ease this transition for fans of the series, an AGI version of the game is also produced, but hardware upgrade holdouts must contact Sierra directly to buy it. The SCI version offers twice the graphic resolution of the former King’s Quest installments, taking advantage of higher-end x86 processors and graphically adroit computers like the Commodore Amiga. Professional composer William Goldstein (tv show Fame, Shelly Long movie vehicle Hello Again) provides forty minutes of scored music for the game, which supports stereo music cards for PCs including Adlib and the Roland MT-32, the latter offering 32-voice capability. Sierra helpfully sells these cards to users who want to upgrade their games to orchestrated sound.

Aside from all the technical mumbo jumbo is the simple fact that in this adventure, the hero is female, a rarity for games of the time. Sierra game designers use the placeholder name Ego to refer to their main characters while developing games; designer Roberta Williams has a hard time grappling with the idea that the “Ego” in this game is a woman. Body language and character movement suddenly becomes a larger issue, and Williams also has to come to terms with the act of killing a female character in the myriad ways typical in a Sierra adventure.

The follow up, King’s Quest V: Absence Makes the Heart Go Yonder, released on floppies in 1990, is in development for 10 months. It is the first game to demonstrate Sierra’s point-and-click interface, allowing users to directly manipulate the world with their mouse pointer instead of having to puzzle out which words are the right ones to type into the parser. It also represents the arrival of VGA graphics to the KIng’s Quest series. By mid-1990, in contrast to the series’ shaky start on the PCjr Sierra has moved six million King’s Quest games off store shelves. KQ5 gets a CD-ROM version in 1991, featuring characters actually speaking dialog, lip-synced with over 50 voice actors. If one yearns to hear what creator Roberta Williams sounds like, pay special attention to Amanda in the Bake Shop. One can also hear Bill Davis, Sierra’s vice president of creative development, as the hermit on the beach. Sierra had broken ground already earlier in 1991 by releasing their first CD-ROM game, a remake of the 1987 Roberta Williams title Mixed Up Mother Goose.

Click button to play Sierra’s first point-and-click adventure game King’s Quest V, on MS-DOS

By the time Roberta starts work on the sixth KIng’s Quest game in June of 1991, she has started feeling confined by having to crank out games in the popular series, so she steps back a bit by bringing in Jane Jenson, co-designer of EcoQuest: The Search for Cetus for the company, as co-designer of the King’s Quest VI project. Bill Skirvin, who had served as Art Director for the previous King’s Quest games, shares directing duties with Williams on what becomes King’s Quest VI: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow in 1992, taking a year and a half to produce with a production budget of over a million dollars. Awaiting gamers are finally welcomed by a startling fully 3D-rendered cinematic opening created by animation and game development house Kronos Digital Entertainment, running 3 minutes for the floppy disk version and expanded to an over 40 meg epic running 7 minutes for owners of CD-ROMS. Adventurers are also treated to such technical progressions in the game as scaling sprites as characters move back and forth around the screen, along with intelligent pathfinding when players click a destination for characters to move around scenes. Sierra also breaks more ground in adventure gaming by having character voice dialog lip-synced to to their mouth movements, a technology the company acquires when they merge with Elon Gasper’s educational software company Bright Star. King’s Quest VI also has Chris Braymen along to create music for the game.

Robby Benson, fresh off the success of his role as Beast/Prince in Disney’s megahit animated movie Beauty and the Beast, heads up the cast of over 30 professional actors who give voice to over 700 total pages of dialog in the game, lending his voice to main character Prince Alexander. Optimized programming, headed by lead programmer Robert Lindsley, also makes things run speedier and smoother. In another technical triumph for the game, the makers manage to squeeze a digitized Top-40 ballad-style song into the finale of the CD-ROM version of King’s Quest VI, titled Girl in the Tower. With music by Mark Seibert, and vocals performed by Bob Bergthold and Debbie Seibert, Sierra sends out copies of the song to various radio stations in an attempt to have it become a hit. Despite encouraging players to call the stations to request they play it, Girl in the Tower fails to escape out of its prison of relative obscurity.

Click button to play multimedia extravaganza King’s Quest VI on MS-DOS

Click button to play Sierra’s Disney-fied King’s Quest VII, on MS-DOS

Roberta Williams’ King’s Quest VII: The Princeless Bride is released in 1994, made with co-director Lorelei Shannon. It features over 100 megabytes of high-quality Disney-style animation, produced by four different animation houses contracted by Sierra. The lush animation is accompanied by over 120 fully orchestrated musical themes from composer Jay Usher, made possible by the room available due to the game’s CD-only release. The 8th instalment of the franchise, the fully 3D King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity, is released in 1998, with Roberta Williams designing the game. While it is the last in the series that enjoys her direct involvement in its creation, it also constitutes a first: it is the only King’s Quest game not featuring King Graham or any of his family as the main protagonists. While Graham makes an appearance in the game, it is focused on the struggle of knight Connor in restoring Graham and the people of Daventry after they are all turned to stone. When the Sierra brand is eventually raised from the ashes in 2014 (spoilers!), the vaunted King’s Quest saga is reborn along with it, reimagined in an episodic game series put out by Sierra and The Odd Gentlemen. Staring in 2015 with King’s Quest : Chapter I – A Knight to Remember, the series moves through five chapters, with an epilogue finishing things off in late 2016.

Designed by Roberta Williams, the King-dom goes 3D in the 8th and final instalment involving Williams,, 1998