Obviously not the same computer as appeared in “An Atari at Thirty” because that was six years ago…

Sometime in 1990, probably early autumn, an Atari Mega 4 computer rolled off a production line in a factory in Taiwan. It was neatly placed into its box, the box was loaded into a container, the container was found a ship to sit in and so the Mega 4 made its way to the UK.

The name Mega 4 was chosen by Atari to reflect the fact that the computer offered four megabytes of memory. At the time this was big. It was fast, neatly designed and capable of running any software that anyone cared to think about. This was moderately reflected in the price – though being an Atari it was way cheaper than less powerful rivals – and so its primary target audience was as the business computer for the high-tech company forging into the future.

In the top right-hand corner of Northamptonshire there was a high-tech company forging into the future by replicating floppy disks. Blank disks came in; software was written onto them; nicely-labelled disks laden with useful things that people would buy came out. Some of this was computer games; some of it was business software for other high-tech companies. Some of it was niche markets for companies which had been high-tech ten or fifteen years previously but had evidently found the upgrade from reel-to-reel tapes too stressful to contemplate repeating. Consequently one healthcare company in the USA was keeping a replicating machine for 8-inch floppy disks in happy gainful employment in Northamptonshire long after all its contemporaries (yes, every other one on the planet) had gone the way of computer valves.

Being high tech and forging into the future, this business needed a suitable computer to manage its affairs. There were older Atari STs knocking around for testing disks and general work, but the serious stuff called for a bigger computer. And so our much-travelled Mega 4 arrived on the scene.

___…___

The Mega 4, and its smaller sibling the Mega 2, was a development of the earlier ST models that offered streamlined circuitry, more memory, minor updates to the operating system (still called TOS) and what might now be viewed as a more conventional appearance – though at the time it was rather radical. Most previous computers had been built into either the keyboard or the monitor. This computer lived in a wholly independent box and everything else, with the exception of a single built-in floppy drive, was a peripheral of some description.

The mouse and monochrome monitor were the same as an earlier 520 or 1040ST. The keyboard was radically simplified to reflect the removal of the computer unit and the general feel was altered by replacing the pads of an early ST keyboard with springs. (At least, the reviewers claimed it was altered. This writer can’t tell the difference, although after 35 years of being battered the 520ST feel may have changed to something akin to a much-used Mega 4.) Software written for the ST could – if it had been written properly – be run on a Mega computer without difficulty. New software for a Mega would obviously have difficulty with the more limited memory of an older ST model.

Atari did some thinking when it came to the design and peripherals. The computer box was perfectly shaped and built for the monitor to sit on top of it, saving space and getting the monitor to a better height. It could be brought up to an even better height by mounting the computer’s box on top of the matching hard drive box (see opening photo). The Mega 4 was also intended to work with a printer. Previous designs of printer, as Atari enthusiastically observed, were designed to take a great tranche of data from the computer and format it for printing. Of course this meant that as long as every computer dumped the same kind of data then any computer could work with any printer. But it also meant that the printer had to be able to process anything that the computer threw at it – which meant it had to have a matching memory and processor banks. Consequently, two computers on one desk – one to work on, and one to do the printing.

Atari decided that if the customer was willing to buy two computers then they would put both inside the computer itself and call the result a memory upgrade. The printer was a large and heavy box with a drum, some laser equipment and a crate of toner inside. The computer did all the processing and sent the printer the results. This made for quicker printing and a cheaper printer – and the computer worked better too.

While Atari were singing and dancing about this in 1990, it is arguable that it was in fact just a development of the approach of 1985 when printers didn’t really format anything and the computer did a lot of the work. It worked perfectly well at the time, but became a dead-end concept a few years later when data processing became so cheap that it wasn’t worth the fuss of producing a dedicated printer range. The results of the policy are quite amusing when a 1985 Atari computer is wired up with a modern printer – the printer, which is the rather more technically powerful piece of kit, is left grumbling impatiently as it waits for the next string of data while the Atari patronisingly and sedately formats the pages.

There were some trade-offs. An early 520ST relies on natural air flow through its copious supply of cooling grills to maintain a reasonable internal temperature, though a cruel observation might be that there is not much going on inside so not much to cool. The Mega 4 has fewer cooling grills (and those which have are placed under the edges of the monitor) and rather more things to run, so it needs cooling fans. Once it is up and running the brain tunes this noise out, but there is a definite sense of “And then there was peace” when a Mega 4 is turned off.

The Mega 4 was capable of booting itself from memory, but likes a floppy disk to poke at while doing so. It boots quicker with one, but will manage a respectable turn-on-to-desktop time of 40 seconds without. (The 520ST is more in the order of 15 seconds, but the writer’s one insists on having a floppy disk. This is quite reasonable; as it has no built-in software then any activities it performs need to be booted off a disk. If no disk is in the drive, then it has no software to boot. If it is not booting any software, then it is not going to be doing any work, and if it is not doing any work then being turned on is a waste of its valuable time.)

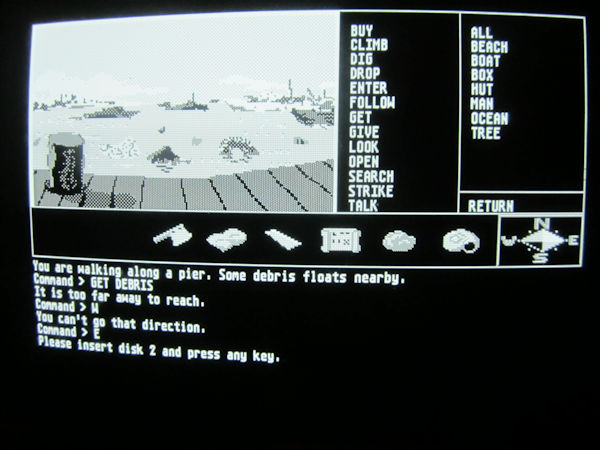

Having a hard drive means that the Mega 4 can save software to it. A 520ST can be fitted with a hard drive to – it is fitted with the necessary ports – but it was more a Thing To Do with a Mega computer. Large and complex pieces of software cannot be run on a 520ST anyway because it is a trifle inclined to forget what it did with the various bits, but they also don’t fit on one floppy disk so booting them would require disk-swapping during loading or operation (Activision’s Mindshadow, for example, comes on two disks and so requires two drives or periodic swapping of the disks.) The Mega 4 can cope with some very large and bulky software, so there is considerable benefit to dumping it off the floppy disks onto the hard drive and running it from there.

An interesting feature of computing is that the average user, being engaged in writing emails, running a couple of minor spreadsheets, browsing news websites and doing basic online shopping, could actually still cope happily with a Mega 4 computer combined with the appropriate free-running processor and software of the time.

___…___

Our specific hero high-tech Mega 4 spent about five years in Northamptonshire, typing letters and dealing with general business matters, with the results being turned out by the high-definition laser printer for posting off to the recipients. For a thought on the high-tech nature of laser printers at the time, it may be worth noting that sixteen years later I would receive the overall summary of my GCSE results on a dot-matrix print-out. Then the high-tech company was, to the annoyance, dismay and inconvenience of many (including both the workforce and the customers of a US healthcare company), quietly liquidated.

After this the Mega 4 briefly went into store at the managing director’s house before the writer’s parents, being friends of the family, stepped in and acquired it. We had moved house by then and were based in South Wales. I vaguely remember looking up from some entertainment with the company owner’s children to see the various component parts being carried out to the car.

With the relatively short voyage complete, the Mega 4 was set up in its new home in the family study. It was a good solid study, full of books and files and computer software. The software had previously been used on the family 520ST, which was shifted to my bedroom along with a wheezing dot-matrix printer.

In its new home the Mega 4 was used for design and typesetting work (in those days more traditional typesetting than what might be immediately thought of by a layperson as design). With the aid of a Handy Scanner and the Calamus layout software it hummed its way through three large and heavy academic books for a Surrey-based publisher.

Saying it hummed its way is really the best way of putting things. It did hum, and hum vigorously. But it also did so with relatively little fuss. There are a lot of family anecdotes about the 520ST. The 520ST is a little slow at talking to its disk drive (which it says is a high-speed disk drive – one wonders what a slow one would be like). It conks out occasionally during data overload, and its memory is limited when dealing with larger documents. But it is a computer of a friendly size that one can relate to.

The Mega 4 just worked, and was generally what we were promised by the computing revolution. It processed things, hummed along, flicked through its documents, stopped to print stuff (for perhaps longer than ideal) and then got on with life. There are no serious stories of evenings patting it down and reassuring it that it can cope with the world. It also did better than Windows in that it didn’t spend every Thursday afternoon sorting its updates and every Wednesday afternoon vaccinating itself against the latest viruses. Stuff just happened. Except possibly on one occasion when I leant over my mother’s shoulder while she was working on it and it promptly fell over – we could only assume that it was unfamiliar with my presence (as I had the 520ST to work with I had very little to do with the Mega 4) and got distracted.

The laser printer became increasingly tired and the Mega 4 was no longer anywhere near top of the range, so with Microsoft’s Windows becoming a stable alternative a new computer was purchased in early 1999. It was a big white thing that ran Windows 98, and it was briefly set up on a corner of the desk that hosted the Mega 4. In due course the computers were swapped to put the Windows machine, with high and proud 1024×860 colour LCD monitor, in prime position; the Mega 4, squat and rounded, took up the corner by the window. Thereafter it was used for writing academic articles while the Windows machine took over the book publishing. About the same time, possibly a little earlier than the Windows 98, a modern Kyocera laser printer arrived to reduce the pressure on the Atari model. It was followed by a fixed scanner to completely remove the need to do scanning with a hand-held unit.

There was a further round of upgrades to the computer kit in 2004 when the Windows 98 computer was relegated to the secondary role by a Windows XP machine with 1280×1024 monitor. This was driven by three things. The Windows 98 was getting old, and was no longer able to play some of my newer software (Transport Tycoon Deluxe was fine, and indeed would probably be fine on the Mega 4, but the 3D-rendering on Jurassic Park was beyond it). A new computer would allow the Windows 98, with its modern standard software, to take up duties as the computer for academic articles (instead of requiring them all to be fed through a converter – First Word Plus produces .doc files that Microsoft Word thinks it can read until it tries to do so). Finally, the Mega 4’s floppy drive was falling out of alignment so that it no longer wrote disks that any other computer could read. Thus the Mega 4 dropped out of traffic and went into the loft for store. There it remained.

The 520ST was displaced to join its fellow in the loft two years later and the Windows 98 lasted another year before the family moved into the all-encompassing embraces of Windows XP. While the Ataris slumbered, the 98 went into a corner of the study and was stripped for spares. I got (and still have, though no longer run) the DVD drive. The monitor is still used as a secondary screen. A booster hard drive went into a successor computer. What couldn’t be recycled was eventually shipped to the council tip, so there will be no 30-year commemoration for that machine.

These XP computers have all gone too, being wiped out in 2013-15 and replaced with Windows 7, 8 and 10 machines. I still have the remains of my XP, though over the course of this year it has been gutted of reusable parts including the hard drive, power supply, graphics card and floppy disk drive. These super-duper Windows 10 machines are now regarded as obsolete by Microsoft, though mine is still running splendidly. But in computer generation terms the Atari era is now a very long time ago…

Two years later I had the 520ST recovered from the loft on some basis or other, and it subsequently did duty as my home computer while I went to university with the Windows XP machine. Aside from a couple of spells for file checking, the Mega 4 saw no further use. It eventually ended up cluttering up a corner of a subsequent study. When we stripped all the Atari floppy disks and shifted the data onto Windows computers it was the 520ST which did the honours (and which by the end of a long night was quietly panting in its corner, murmuring things about brutality and conventions limiting the number of disks that a computer is required to read in a day).

The Mega 4 has now spent over half its life out of regular use, and there is a certain temptation to wonder why it survived. The simple answer is probably that it worked, and this family does not throw away kit that works. Three Windows computers have been withdrawn and gutted for reusable parts – but they had stopped working. Windows machines do. The 520ST got to watch from across the room as its Windows successor, once so top-of-the-range that its quad-core processor hadn’t been manufactured in time for the shipping date, deteriorated into a dribbling wreck with insufficient processing power to open the Control Panel and check its purported capabilities. That XP was booted up a couple of times after withdrawal to aid fault-finding with its own successor. It had occasional problems processing mouse movements.

But neither Atari machine ever totally died, and in any case the only value of the components is repairing the other – which requires one of them to break enough to need it. The Mega 4 is certainly not a totally happy computer today. The floppy drive is out of alignment, so it can’t talk reliably to other machines. The mouse is shot, and ideally the 520ST’s mouse gets borrowed for the purpose. (Ironically after an incident where the 520ST’s mouse stopped working in the middle of writing something the Mega 4’s mouse was invited back to substitute. The swap lasted about two weeks. Then I packed it in and decided to gamble on the 520ST’s mouse again. That one hasn’t given grief since.) The printer is apparently dead. A part of its survival is that I have always wanted to have the monitor on hand in case the one attached to the 520ST gave grief. (Actually the Mega 4 had managed to come into the original 1985 monitor and the 520ST had the Mega 4’s 1990 one, so there was also the incentive to keep hold of all the 1985 kit. Unfortunately the 1985 monitor had become inclined to uncertainty as to what size its screen should be – but, in typical Atari fashion, after being informed that it was becoming liable to be swapped out again it bucked up its ideas, settled down, stopped flickering and has reverted to being the reliable piece of kit promised by its instruction manual. The two computers seem to have a certain competitive spirit – the 520ST at least seems to be unwilling to entirely pack it in before the Mega 4 does.)

Still, the Mega 4 boots up as fast as ever, the software is all there and the components – barring the printer – all talk to each other. And the SLM605 printer is not a mandatory addition. The computer has a parallel port in the back that allows it to speak to any printer with a matching cable. The old Kyocera is now spare. If it had to be a working computer and print stuff, it could use that. It could probably be wired to an external floppy drive too, but now so few other computers have floppy drives a working one on a computer with a hard drive is of mixed value.

A perpetual question is why it has not lasted quite so well as its 520ST sibling. The 520ST was already ten years old when the Mega 4 arrived. It had been used for writing several computer programmes, various essays, a PhD and two whole academic books. Since then it has played numerous games, been worked enthusiastically by many happy visiting children (for some of whom it was their first meeting with a proper computer), written homework, essays and coursework, drawn endless pictures and been my go-to machine for outpourings of imagination into story-writing. Generally I think I get better stories out of the Atari than out of a Windows computer.

Of course the 520ST has given problems too over its thirty-six years. The first to come to mind is an occasion in 2012, just before I left home, when it suddenly stopped working and I thought I’d lost it forever. Actually the “on/off” switch needed cleaning. The “B” drive added much interest to my GCSE coursework and I went through a spell of maintaining a fleet of single-sided disks, partly because they seemed to be more reliable and partly because if the worst happened the “A” drive could read them. In the short-term I managed the “B” drive through the coursework by sitting it on my knee and stroking it – it seemed to appreciate this, and it calmed me down – and since then it has whirred peacefully into long quiet evenings with no challenges. Last night the 520ST was happily supporting a tour of the Great Underground Empire on Zork I, apparently enjoying throwing up Infocom’s often unhelpful retorts to instructions.

A sign of this thrashing can be seen on the keyboard, which has an appearance of being used in a way that the Mega 4 does not.

Maybe as computers have developed they have just been inclined to not last as long. The 520ST did fifteen years solidly and has been used intermittently for another twenty. It may yet get to be the first computer for another generation. Parental Controls on an Atari computer simply involves hiding the box of floppy disks. The Mega 4, by contrast, managed ten years fairly solidly and another five years more intermittently. The Windows 98 coped with six. Improvements to computer power and memory means that there is now further to fall before they conk out; possibly Microsoft better manages the design of their updates and anti-viruses have become less inclined to side effects. Anyway, the successor computers have managed between six and nine years (though the nine might have been pushing it) and various laptops and tablets have generally managed two to four (or five at a push). My phone almost made it to ten years old, mostly by ignoring the fact that several of its features no longer work. Like the Atari computers, it has never really made much of being updated. Nowadays this 2011 Samsung smartphone is a very happy portable radio.

Which is possibly the answer to computer longevity. Disconnect it from the Internet, turn of its update functions and let it get on with life. If you need to send someone a document, print it out and post it.

In the long run, that may be better for the environment anyway. I would have to compare the speed at which my electricity meter turns in order to assess the relative power consumption rates of a 1985 Atari and a 2015 Windows 10 PC. But what I do know is that the Atari required rather fewer precious metals to build it, and the energy consumed to build the Atari is being depreciated over rather more years.

Not that I would be in a rush to rely entirely on the Mega 4 for my heavy-duty needs. It does have the processing power for all of what I need to do and a lot of what I want to do (there are exceptions around photo management and using some simulator software). But even if the printer did work I would still struggle to work out how to get the best from it – the manual is for the other Atari laser printer model (no idea why). Its hard drive is perhaps a little undersize (apparently this encourages orderly filing and data management). The mouse is still dead. And those Atari monitors, which the manual proclaims will provide “years of reliable high performance”, perhaps seem a little small.

At least, I say they seem a little small. They are bigger than my tablet computer. My cheapo widescreen computer monitor can show two pages on one screen or one page with massive sidebars. Perhaps actually the Atari is about right…

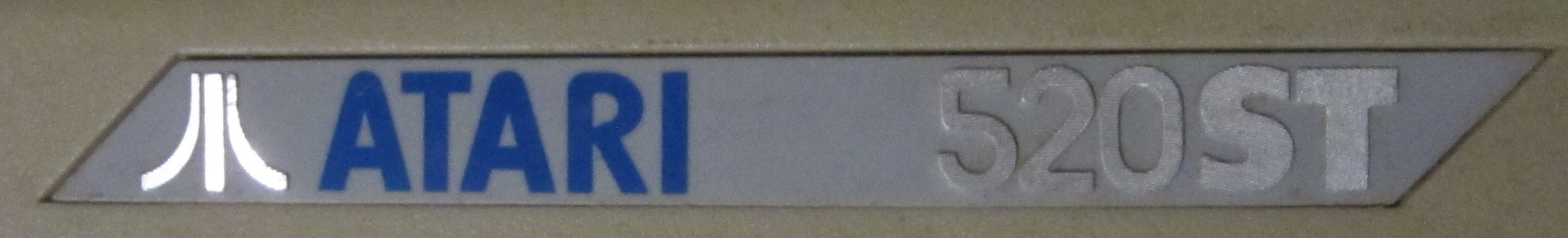

An Atari computer. Note keyboard, monitor, two disk drives, mouse and desk light.

An Atari computer. Note keyboard, monitor, two disk drives, mouse and desk light. The Atari brand, next to a computer model number.

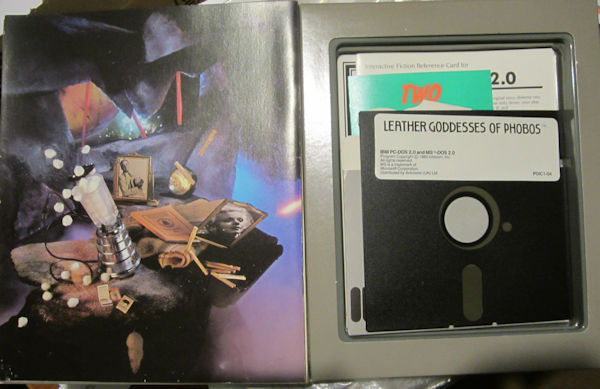

The Atari brand, next to a computer model number. Early 1980s white-hot technology – the 5-inch disk. This example contains (or contained – it hasn’t been checked for whether it still works lately) a piece of software innocently called “Leather Goddesses of Phobos” – Phobos of course being one of the moons of Mars. In those days floppy disks were actually floppy, both in terms of the disk itself and when it was in its nice little case. The 3½-inch design has a rigid plastic shell, a metal cover for the exposed bit of disk and a proper grip in the centre for the drive to hold. Humorous anecdotes abound of incidents encountered by computer experts during the conversion process from 5-inch to 3½-inch disks, all of which are now largely lost to posterity because hardly anyone is interested in floppy disks any more.

Early 1980s white-hot technology – the 5-inch disk. This example contains (or contained – it hasn’t been checked for whether it still works lately) a piece of software innocently called “Leather Goddesses of Phobos” – Phobos of course being one of the moons of Mars. In those days floppy disks were actually floppy, both in terms of the disk itself and when it was in its nice little case. The 3½-inch design has a rigid plastic shell, a metal cover for the exposed bit of disk and a proper grip in the centre for the drive to hold. Humorous anecdotes abound of incidents encountered by computer experts during the conversion process from 5-inch to 3½-inch disks, all of which are now largely lost to posterity because hardly anyone is interested in floppy disks any more. Quality graphics, 1980s style – comet-shooter Megaroids.

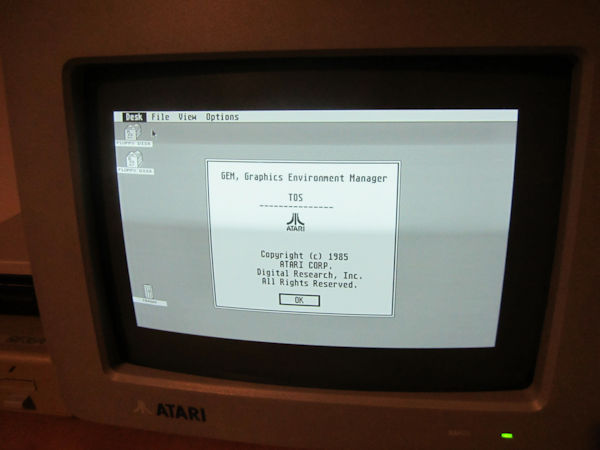

Quality graphics, 1980s style – comet-shooter Megaroids.  GEM was the desktop system. TOS is the operating system. Note the lack of information on irrelevant points like CPU and RAM. Staring at an early Atari for a couple of minutes trying to trace details of its memory capabilities is usually followed by remembering what the “520” on the case is a reference to. The designers, having invented the desktop, then turned their attention to what to do with it – being able to open windows on the desktop showing the contents of both disk drives is very handy, but when they’re closed it represents over 300,000 mostly grey pixels. The Atari computer family kept the grey background to the end. Nowadays a nice picture or a corporate logo is preferred. The pale zone across the screen is due to the camera picking up the refresh rate that the human eye normally doesn’t capture; there is nothing wrong with the monitor. The unused black border to the illuminated screen is an intentional curiosity of the design.

GEM was the desktop system. TOS is the operating system. Note the lack of information on irrelevant points like CPU and RAM. Staring at an early Atari for a couple of minutes trying to trace details of its memory capabilities is usually followed by remembering what the “520” on the case is a reference to. The designers, having invented the desktop, then turned their attention to what to do with it – being able to open windows on the desktop showing the contents of both disk drives is very handy, but when they’re closed it represents over 300,000 mostly grey pixels. The Atari computer family kept the grey background to the end. Nowadays a nice picture or a corporate logo is preferred. The pale zone across the screen is due to the camera picking up the refresh rate that the human eye normally doesn’t capture; there is nothing wrong with the monitor. The unused black border to the illuminated screen is an intentional curiosity of the design. The dusty hulking floppy disk transformer makes a rare public appearance. It is the smaller of the two. Note Atari was proud enough of it to brand it (top right corner). The UK-standard plugs for the monitor, computer and disk drives lie in the background for scale. Behind is the computer unit (with grill) lumped onto the back of the keyboard. Note stylish angles and curves.

The dusty hulking floppy disk transformer makes a rare public appearance. It is the smaller of the two. Note Atari was proud enough of it to brand it (top right corner). The UK-standard plugs for the monitor, computer and disk drives lie in the background for scale. Behind is the computer unit (with grill) lumped onto the back of the keyboard. Note stylish angles and curves. The computer from above. The clean-lined QWERTY keyboard is of course the prominent feature. The function keys (10 of them) are neatly stylised across the top. Beyond the deep vein is the actual computer block, a little under 3 inches wide and about 19 inches long, with its angled air-vent grill. The Atari logo seen towards the top of this post is at the top right of the keyboard. The three remaining connector leads extend out the back, with the mouse feeding off to the right.

The computer from above. The clean-lined QWERTY keyboard is of course the prominent feature. The function keys (10 of them) are neatly stylised across the top. Beyond the deep vein is the actual computer block, a little under 3 inches wide and about 19 inches long, with its angled air-vent grill. The Atari logo seen towards the top of this post is at the top right of the keyboard. The three remaining connector leads extend out the back, with the mouse feeding off to the right. The back of the keyboard, with the floppy lead nearest. Behind is the smaller monitor cable, with the black power supply furthest away. In the foreground a USB connector provides some sort of scale. The port on this side of the floppy lead is for the hard disk; the modem is hidden behind the floppy wire and the printer is beyond that.

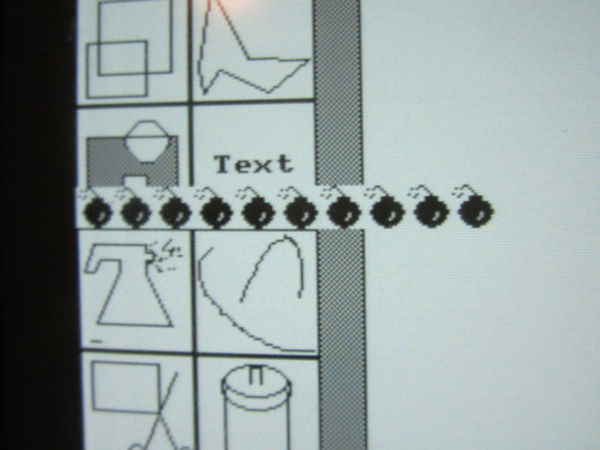

The back of the keyboard, with the floppy lead nearest. Behind is the smaller monitor cable, with the black power supply furthest away. In the foreground a USB connector provides some sort of scale. The port on this side of the floppy lead is for the hard disk; the modem is hidden behind the floppy wire and the printer is beyond that. This particular example of “bombing out” was cruelly induced for your enjoyment with the help of a known bug in the relevant piece of software. How the Atari programmers managed to arrange for a bit of the processor to survive the crash and provide the bombs is an interesting question.

This particular example of “bombing out” was cruelly induced for your enjoyment with the help of a known bug in the relevant piece of software. How the Atari programmers managed to arrange for a bit of the processor to survive the crash and provide the bombs is an interesting question. A Mega4 sans desk (they prefer desks when out for more than a few minutes). The computer is now in the box under the monitor and the floppy drive is tidily tucked away inside it, along with a decent chunk of memory capable of handling all the contents of a high-density floppy disk. The 520ST resolves the problem of high-density floppy disks being three times the size of its memory by not being able to read them. (This example, when in the full flight of its career with a book designer, also had a separate hard drive plus the mysterious sounding “B: Phantom Disk”.) The mouse, lost amongst a pile of paperwork on the right, is unchanged from 1985. The keyboard is now just a keyboard, but the decorative diagonal lines reminisce about former times. Both designs have a lot of diagonal lines. Atari seemed to like diagonals.

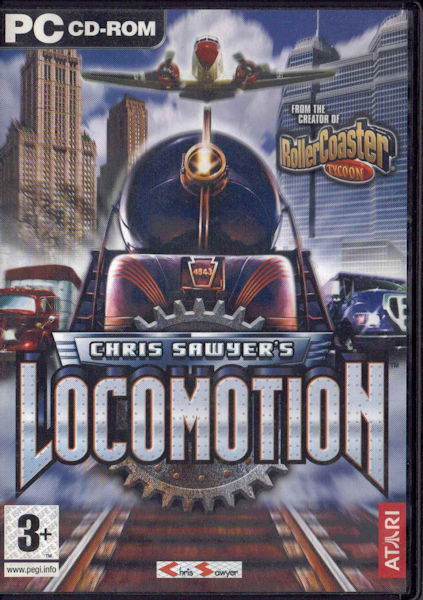

A Mega4 sans desk (they prefer desks when out for more than a few minutes). The computer is now in the box under the monitor and the floppy drive is tidily tucked away inside it, along with a decent chunk of memory capable of handling all the contents of a high-density floppy disk. The 520ST resolves the problem of high-density floppy disks being three times the size of its memory by not being able to read them. (This example, when in the full flight of its career with a book designer, also had a separate hard drive plus the mysterious sounding “B: Phantom Disk”.) The mouse, lost amongst a pile of paperwork on the right, is unchanged from 1985. The keyboard is now just a keyboard, but the decorative diagonal lines reminisce about former times. Both designs have a lot of diagonal lines. Atari seemed to like diagonals. A 2004 computer game. Note the publisher label at bottom right.

A 2004 computer game. Note the publisher label at bottom right. Disk drives down the years. Bottom to top: the Atari’s “A” drive, the independently-provided “B” drive and a modern USB floppy. The Atari drives spent a third of their lives in one desk structure which hid most of the “A” drive from sunlight, so only the front of the drive has faded to yellow. The back of the drive remains in broadly its original shade.

Disk drives down the years. Bottom to top: the Atari’s “A” drive, the independently-provided “B” drive and a modern USB floppy. The Atari drives spent a third of their lives in one desk structure which hid most of the “A” drive from sunlight, so only the front of the drive has faded to yellow. The back of the drive remains in broadly its original shade. The ST’s mouse. Readers using a computer with a mouse may wish to compare how far styling has come down the years. Underneath is the once-conventional ball (which went out, along with connecting leads, around 2000). Two buttons are provided, unlike the single-button Apple mouse of the time, but there is no tracker wheel. The Mega4 came with a mousemat (in Atari grey), which is now the only bit of that particular Mega4 still in commercial use. Consequently the ST has to make do with a natty blue number.

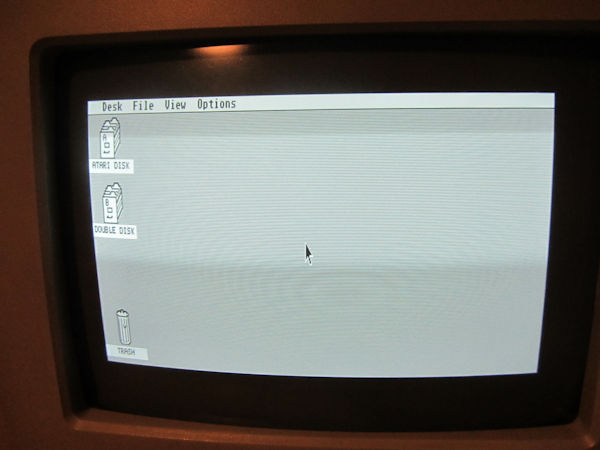

The ST’s mouse. Readers using a computer with a mouse may wish to compare how far styling has come down the years. Underneath is the once-conventional ball (which went out, along with connecting leads, around 2000). Two buttons are provided, unlike the single-button Apple mouse of the time, but there is no tracker wheel. The Mega4 came with a mousemat (in Atari grey), which is now the only bit of that particular Mega4 still in commercial use. Consequently the ST has to make do with a natty blue number. Low resolution. On high resolution, when the computer is running itself in its usual way, both disk drive icons are called “Floppy disk”. The emulator renames them as “Atari disk” and “Double disk” which does rather reflect the respective drive’s capabilities. The trash can at the bottom eats anything which wants deleting, except random non-existent files which Windows likes to install on floppy disks to confuse hapless Ataris. This necessitates knocking the “write” function off Atari-used floppies before feeding them to modern computers. The nature of the Atari’s residual memory means that anything that goes in the trash can stays there; extraction is an awkward process that only works if nothing else has been written to the disk since deletion. (Essentially the computer deletes the name attached to the collection of 0s and 1s that make up the file on the disk but leaves the binary code in place until it actually needs to rearrange it for another file; the code can still be read until the rearranging takes place if the disk with the necessary software still works.)

Low resolution. On high resolution, when the computer is running itself in its usual way, both disk drive icons are called “Floppy disk”. The emulator renames them as “Atari disk” and “Double disk” which does rather reflect the respective drive’s capabilities. The trash can at the bottom eats anything which wants deleting, except random non-existent files which Windows likes to install on floppy disks to confuse hapless Ataris. This necessitates knocking the “write” function off Atari-used floppies before feeding them to modern computers. The nature of the Atari’s residual memory means that anything that goes in the trash can stays there; extraction is an awkward process that only works if nothing else has been written to the disk since deletion. (Essentially the computer deletes the name attached to the collection of 0s and 1s that make up the file on the disk but leaves the binary code in place until it actually needs to rearrange it for another file; the code can still be read until the rearranging takes place if the disk with the necessary software still works.) Medium resolution – for completeness. Weirdly thin and presumably provided so that colour monitor users could look at text documents.

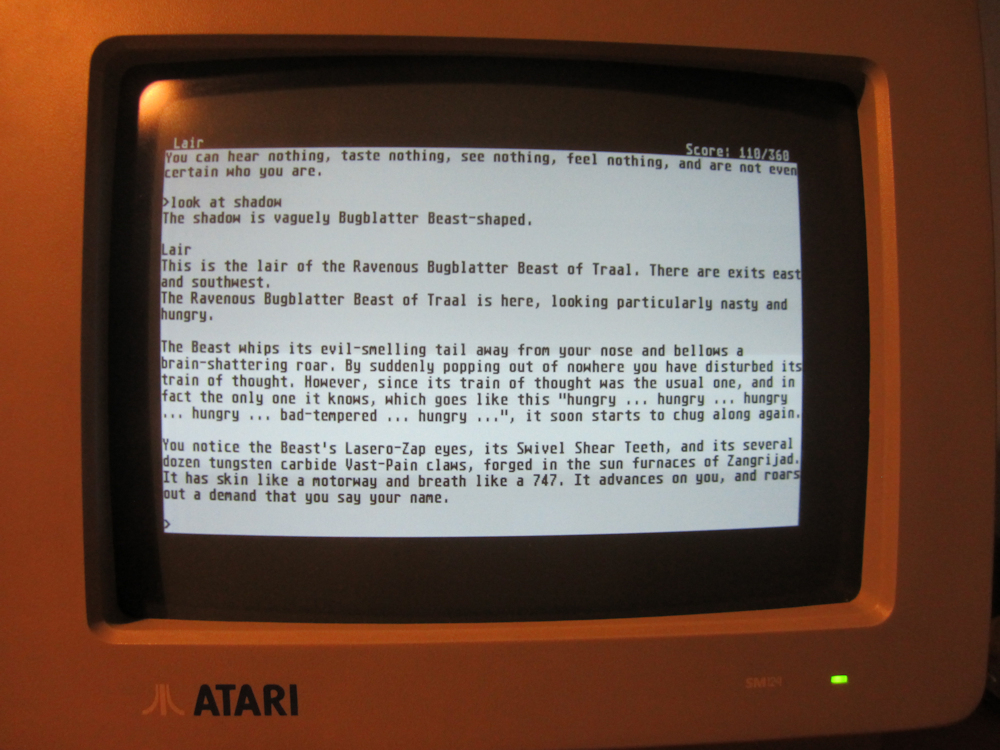

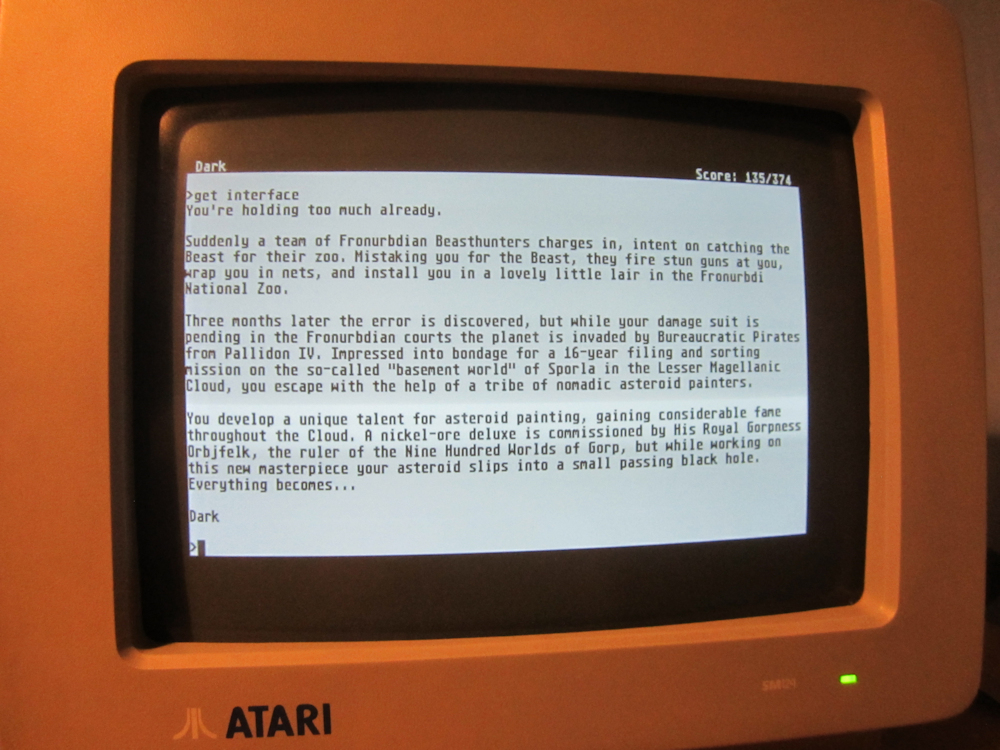

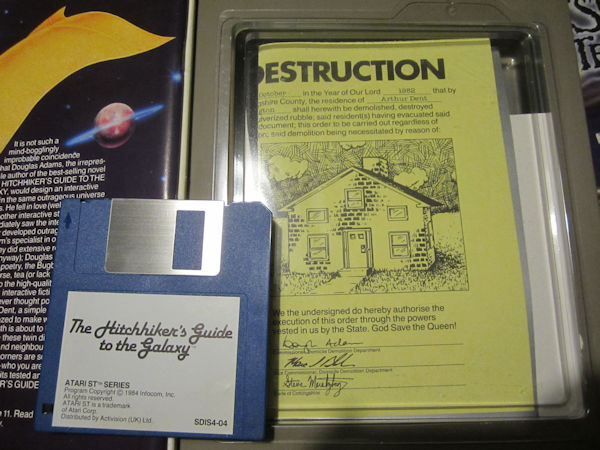

Medium resolution – for completeness. Weirdly thin and presumably provided so that colour monitor users could look at text documents. Infocom made the computer game of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (a few dozen lines of code for The Restaurant at the End of the Universe also exist out there). This is the original packaging with original disk – it can now also be found in a

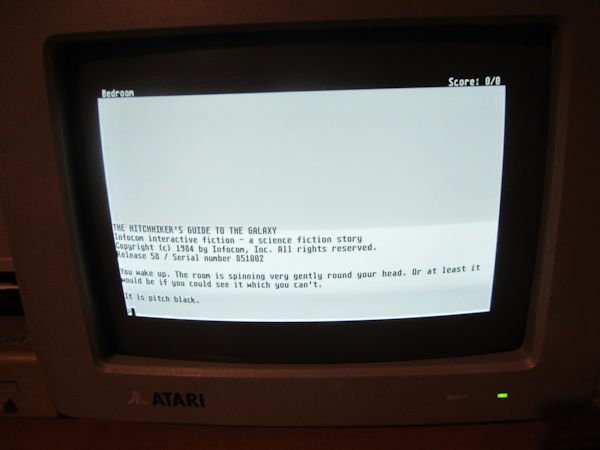

Infocom made the computer game of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (a few dozen lines of code for The Restaurant at the End of the Universe also exist out there). This is the original packaging with original disk – it can now also be found in a  As intended by its creators – how the computer game for one of the world’s more famous stories appeared to the original players. Infocom ran all their games with what was essentially an emulator, allowing the emulator to be tailored to each operating system and the game to remain the same. Making the whole Infocom collection available online to Windows users therefore will not have been much more difficult than updating the Windows emulator and accompanying it with the 1980s code for the games. The BBC now owns Hitchhiker’s; Activision, who bought Infocom in 1986, put Zork 1 on one of its more recent games as a random feature; the other 33 lie largely forgotten.

As intended by its creators – how the computer game for one of the world’s more famous stories appeared to the original players. Infocom ran all their games with what was essentially an emulator, allowing the emulator to be tailored to each operating system and the game to remain the same. Making the whole Infocom collection available online to Windows users therefore will not have been much more difficult than updating the Windows emulator and accompanying it with the 1980s code for the games. The BBC now owns Hitchhiker’s; Activision, who bought Infocom in 1986, put Zork 1 on one of its more recent games as a random feature; the other 33 lie largely forgotten. Mindshadow – an Activision game with pictures. It has some good lines (“The boat isn’t seaworthy. It couldn’t save lives in a bathtub”) but lacks the multiple solutions multi-threaded approach of Infocom games. This makes it easier to play, but less satisfying to return to. The text below the illustration and the inventory (an axe, a bit of canvas, a lump of steel, a map, a rock and a shell) reflects the other problem with the pictures – it means managing a game on two disks.

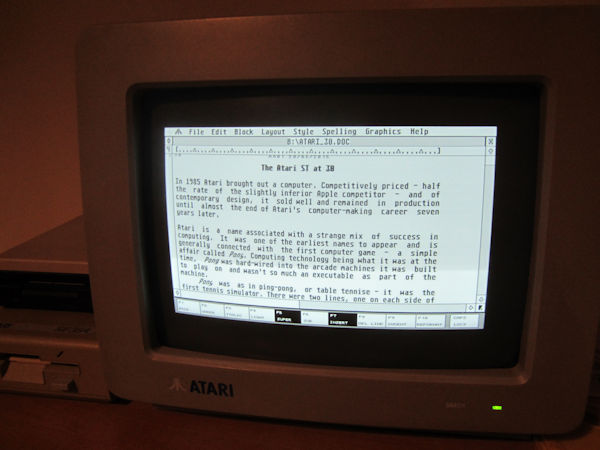

Mindshadow – an Activision game with pictures. It has some good lines (“The boat isn’t seaworthy. It couldn’t save lives in a bathtub”) but lacks the multiple solutions multi-threaded approach of Infocom games. This makes it easier to play, but less satisfying to return to. The text below the illustration and the inventory (an axe, a bit of canvas, a lump of steel, a map, a rock and a shell) reflects the other problem with the pictures – it means managing a game on two disks.  This blogpost, on 1st WordPlus, after being written. WordPlus has a spell checker but it’s a little rough-and-ready so usually I don’t bother. Formatting tools, at the bottom, use the function keys for keyboard shortcuts. Subject to computer memory restrictions, the programme will open four documents at once.

This blogpost, on 1st WordPlus, after being written. WordPlus has a spell checker but it’s a little rough-and-ready so usually I don’t bother. Formatting tools, at the bottom, use the function keys for keyboard shortcuts. Subject to computer memory restrictions, the programme will open four documents at once.