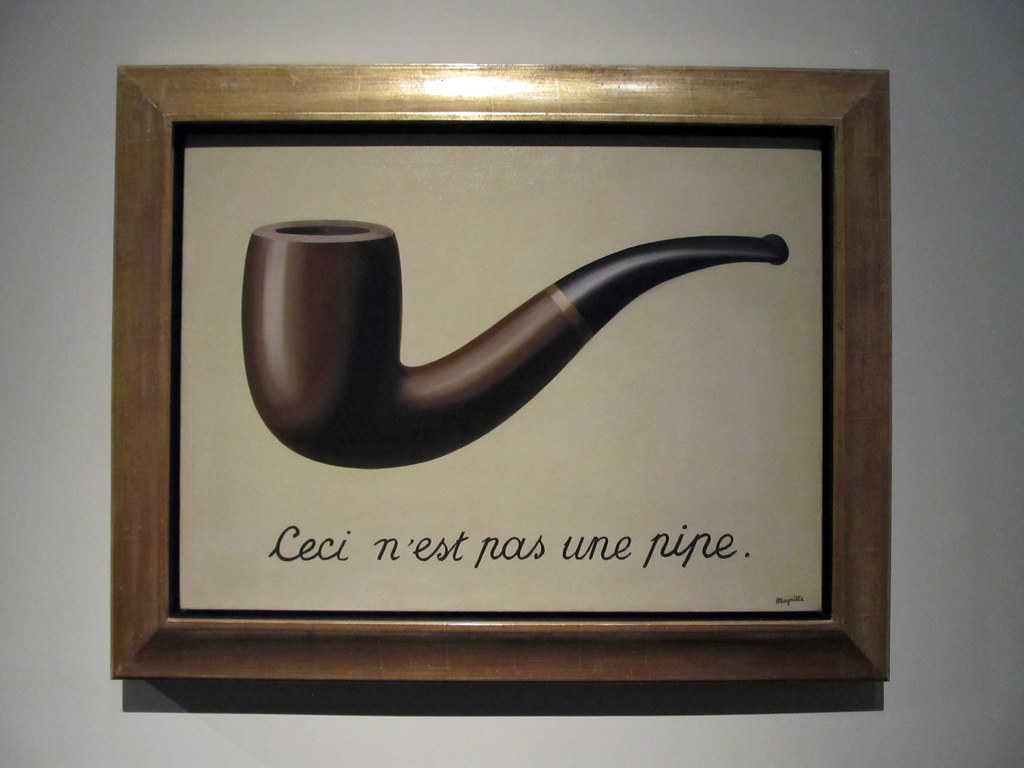

René Magritte’s 1929 painting “The Treachery of Images,” currently on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, presents a pipe with a French subscript proudly proclaiming, “This is not a pipe.” Well, then what is it? It’s an image of a pipe, not an actual pipe. Michel Foucault, a late 20th-century French philosopher, said Magritte’s painting is “as simple as a page borrowed from a botanical manual: a figure and the text that names it.” Though the painting begs to be seen as blameless and simple, its perceived innocence may just veil a pernicious attack.

The contradiction inherent to the painting is a conflict in language. Above the word “pipe” is an image of a pipe. Aren’t words just other types of images? Neither words nor pictures are the “real” thing, yet both are acceptable alternatives. Neither the word nor the brown-and-black painting are actually pipes, but they are references to the real thing. Is there even a difference?

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed the birth of a philosophical movement that defied reality, literally, and may just have the answer to our problem. Postmodernism, at its most unitary form, is defined best by Jean-Francois Lyotard as an “incredulity towards metanarratives,” where metanarratives is taken to “mean a theory that tries to give a totalizing, comprehensive account to various historical events, experiences, and social, cultural phenomena based upon the appeal to universal truth or universal values.” Nothing is objective or universal to a postmodernist, not even truth. It is very much a reactionary movement against modernism, whose goal was to encapsulate the world’s experiences into these metanarratives. Examples include democracy, capitalism, communism, religion, progress, reason, and language. In a world ravaged with conflict over which of these metanarratives should ultimately win over, postmodernists wished to deny them all, in favor instead of a more subjective and pluralistic experience.

Jean Baudrillard, perhaps the most influential postmodern philosopher, questioned the nature of reality in his book, “Simulacra and Simulation,” where he attempts to prove that man lives in a hyperreality defined by symbols and images that have replaced the real thing. For example, if I wanted to skip school tomorrow, all I need to do is cough a few times, pat a warm towel over my forehead, and stay in bed. For all concerned, I am as good as sick because I have produced the image of illness. The reality of whether or not I actually have been infected by a virus no longer matters. The nature of this new reality is populated with mechanisms that no longer refer to the real, but instead replace it.

Examples of the hyperreality abound before us. Your neighbors spend much time, energy, and resources in maintaining a clean and manicured lawn, but that isn’t how nature works. Trees that may drop one too many acorns don’t naturally lose branches, bushes don’t grow in squares, and flowers the colors of a rainbow don’t originate in residential neighborhoods, yet that has become the norm. Disneyland is probably the most famous example of the hyperreal. With a “Main Street” lined with old-timey mom-and-pop shops and several life-sized houses from a distant past, we are made to feel Disneyland is a fantastical transport to an experience we are no longer privy to, but it is all just as arbitrary and artificial as anything else. If you listen to the bored teenagers in Mickey Mouse ears as they tell you where to sit and put your hands, you may just experience the “Mark Twain River Ride,” but that is only an idea of how the past was, simulated in another environment for our own enjoyment. The conceit of the hyperreality we inhabit is that everything is supposed to make us feel we are living in a pure or original world, but we don’t.

The Kardashians are not real people. For years, we have tuned into E! Network to watch the top 1% argue over meaningless things like earrings in the ocean because they are just so relatable. We love Khloé Kardashian because she is the “realest one,” and we love Kris Jenner because she is just so sassy and smart. Who cares? That’s not how real people act, yet they make millions from us believing they do. America is obsessed with reality TV because we are sold this idea of a no-holds-barred, behind-the-scenes look at someone’s life, but it is all doctored and staged for marketable moments we can all tweet about later, and even though we know that, we just don’t care. Moreover, if you’re sitting there thinking, “This surely doesn’t apply to me, I hate reality TV, cheers to my own intellectualism,” you’re still guilty of playing into the hyperreal. All movies and television are simulations of reality we buy into. I love Game of Thrones because Sansa Stark is so powerful and grounded despite her endless misfortune, but that isn’t a real person. She was written to be liked, yet that facade disappears whenever I start the next episode. The Kardashians nor the Starks are moored in the real world, but because a particular image of them exists in media, that representation is now just as good as the real thing, and that’s why images can be so dangerous.

My generation is probably the one most victimized by the hyperreal. We have this flawed view of social media as a tool that can help us peer into the lives and experiences of people all across the world, but that is exactly what it isn’t. Teenagers post pictures of themselves smiling with their romantic partners, living it up at some exclusive beach resort, or even looking “snatched” at some fancy event. What if they fought with their partner right before the picture was taken, had a horrible time out on vacation, or actually looked terrible and somehow managed to produce one good picture? It doesn’t matter. We choose what people get to see on social media, and it allows us to construct a narrative independent of our actual personalities, divorced from reality.

Finstas, too, are even more postmodern. On top of the artificial superficiality of our regular Instagrams, we feel the need to feign vulnerability by creating fake accounts we can show our “true selves” on, which only perpetuates the issue by communicating supposed honesty through a dishonest medium. It is artifice layered on artifice. Even “social justice warriors” on Twitter who are always getting angry about something on the forefront of our next public “cancelling” are manufacturing an image of themselves that appears “woke.” People will change their profile pictures to blue in support of Sudan or write 140 characters about how much they hate Jeffree Star, but it isn’t actually in the interest of public good. It is all a worthless attempt to appear politically-correct, politically-active, or politically-versed. The reality of whether or not these fiery debates or Twitter threads actually contribute to an effective public discourse or reveal some semblance of true knowledge or good intention no longer matters. It is the symbol of knowledge that these people care about, not its reality. If I never talk about political issues in real life, but my Twitter feed is flooded with retweets and likes of news and partisan opinions, then the image I have created of myself online can be believed to be my true self, but it isn’t.

Plastic surgery, photoshop, vintage clothing, CGI, Times Square, supermarkets with all their products on the edge of the shelves: none of it is natural or honest, yet our new reality is flooded with it. Foods with GMOs, old-looking cars, even buildings with architectural styles foreign to their time or place are all examples of the hyperreal as well. It is almost like Reality+. We once had an original world with original people, foods, and places, but now we only have images of people, either in our heads, social media, TV, or even in person, when people pretend to be people they aren’t in order to simulate a certain personality. Our foods are processed, modified, and packaged to our pleasure. Our schools, workplaces, and homes are amalgams of foreign cultures and styles maintained with unnatural levels of order and cleanliness to produce our new incarnation of reality. It’s possible these instances of hyperreality are natural progressions caused by evolving technology, but that only further proves how suspicious we should be of images.

This is by no means a new phenomenon, either. Protestant iconoclasts in the 16th century destroyed any and all images of God because they implicitly understood the conceit of Postmodernism long before it was even a thought. If you manufacture an image of an idea, that idea will soon lose its value, and we will begin to worship the image instead. Most representations of Jesus Christ circulated today depict a white, long-haired man. Jesus was Middle-Eastern. In reality, he probably would’ve had shorter hair and darker skin, but that fact doesn’t matter, because the image exists, and that is as good as real.

René Magritte was not a postmodernist. Though his painting perfectly encapsulates the problem with images and language, he was only an early prophet of the philosophy. He warned us early on that our equating words and images to their referents would only allow them to soon assume the guise of reality. The purpose of Postmodernism is not to make us resign to the fact that nothing is real, but to make us skeptical of what is presented before us. We use the word “trees” to refer to those big green leafy things outside our window, but those could have easily been named “apples” or “boats” centuries ago. Language is arbitrary, but believing language is interchangeable with the real world is the root of the problem. Words and images are pernicious tricksters, and if we constantly allow them the undue power we’re used to giving them, we may end up deceptively buying what’s sold to us to the point we completely forget the world we once inhabited.

Categories: Philosophy