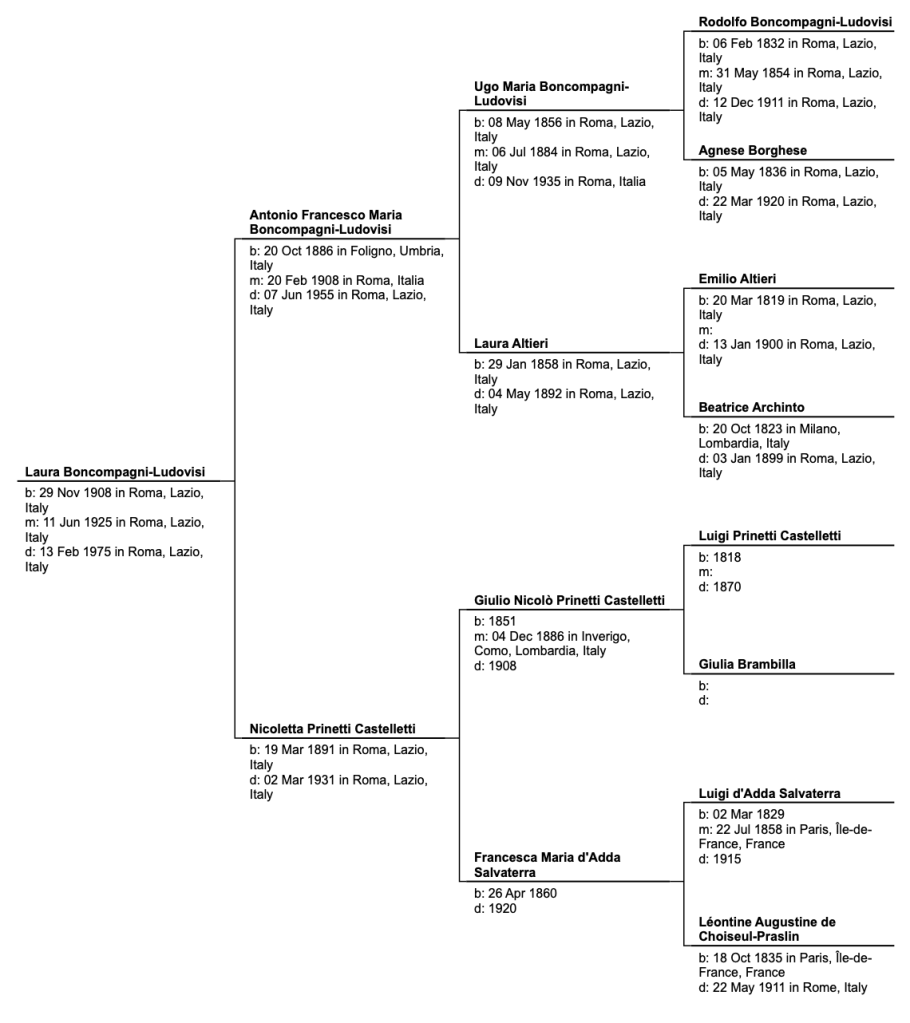

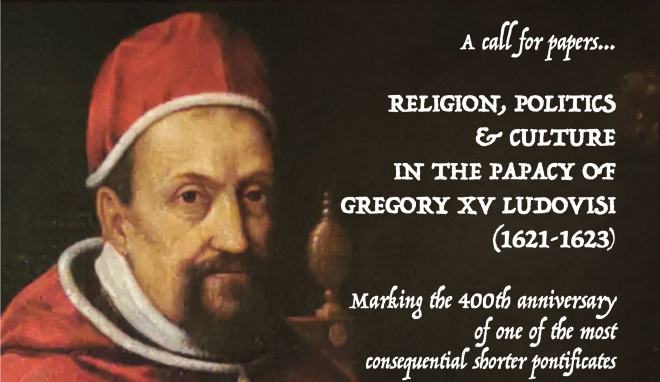

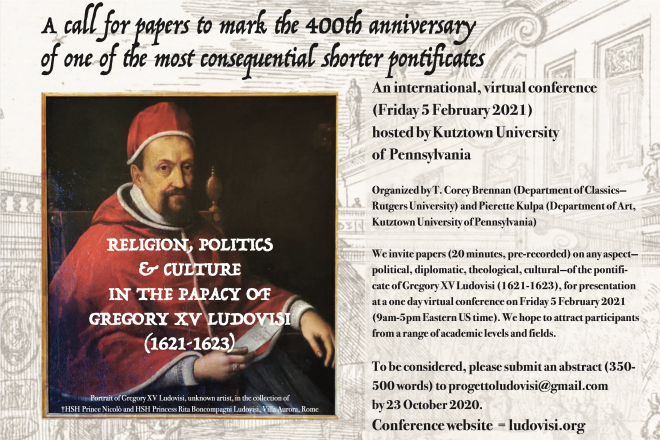

By T. Corey Brennan (ADBL editor) and Hatice Köroglu Çam (Temple University)

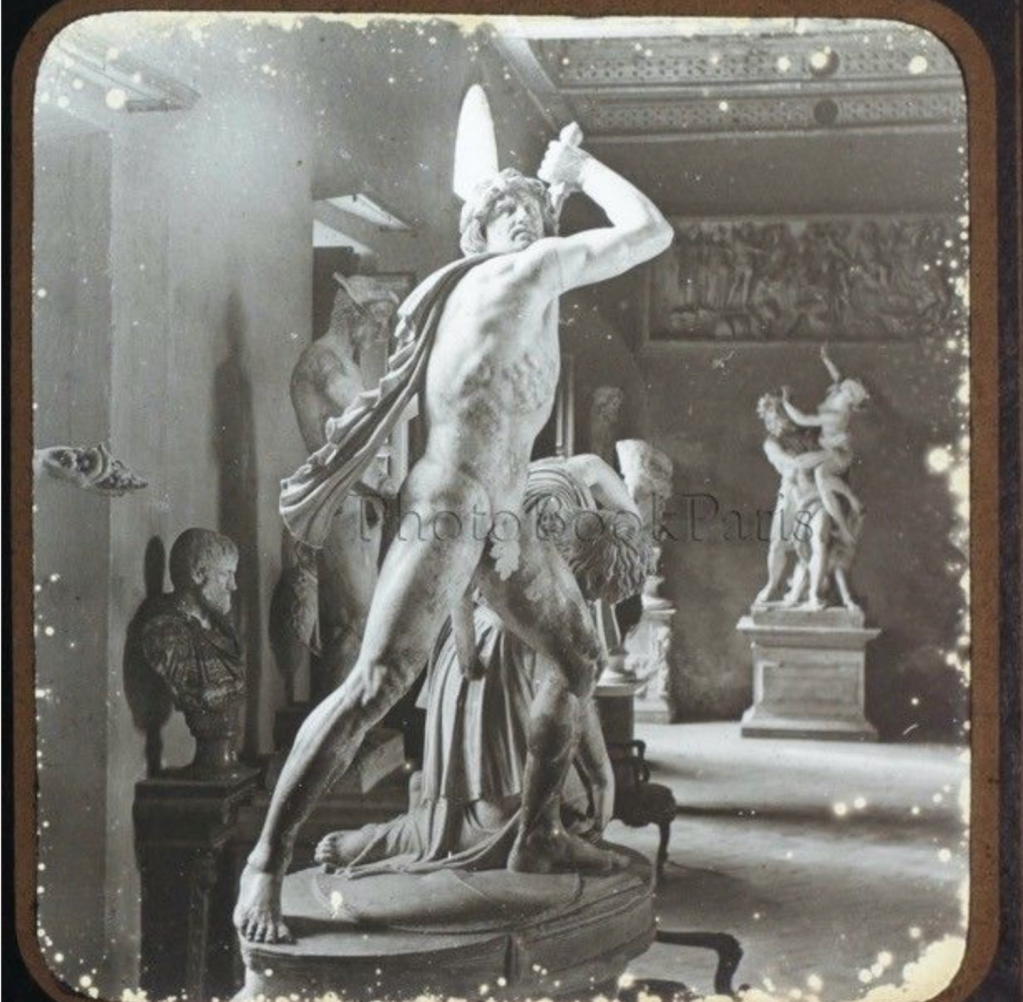

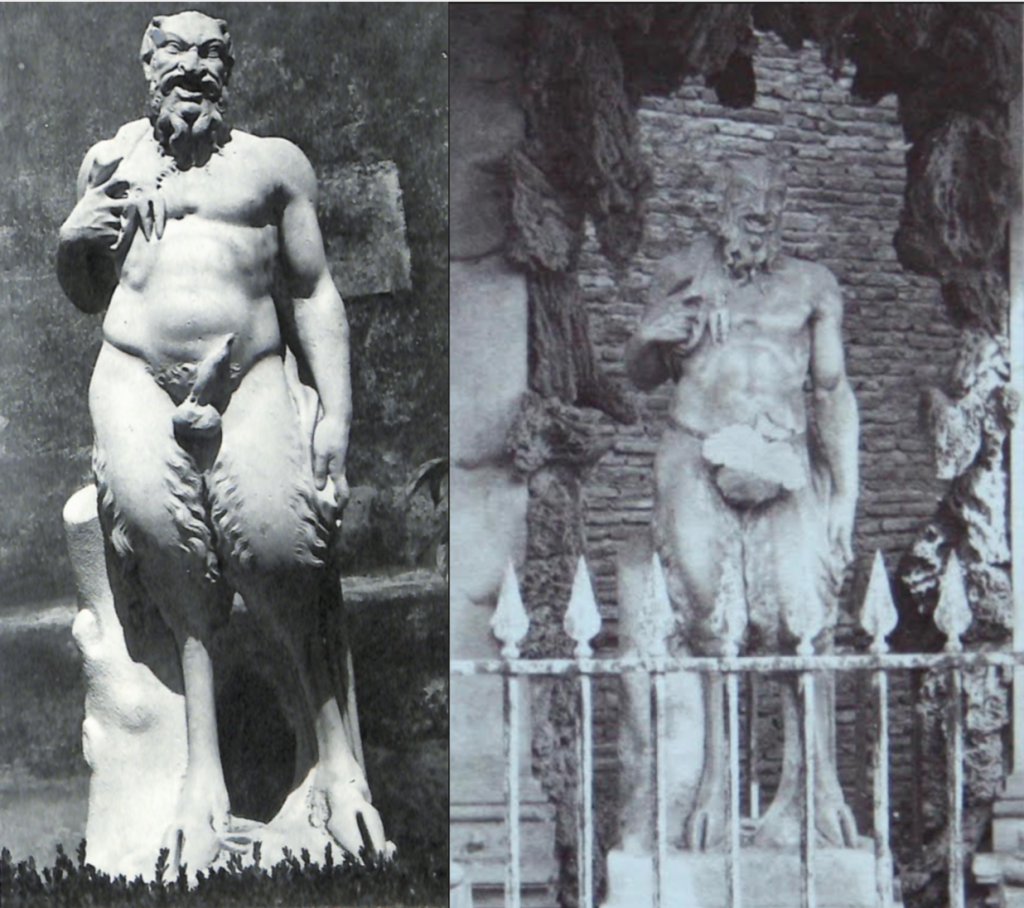

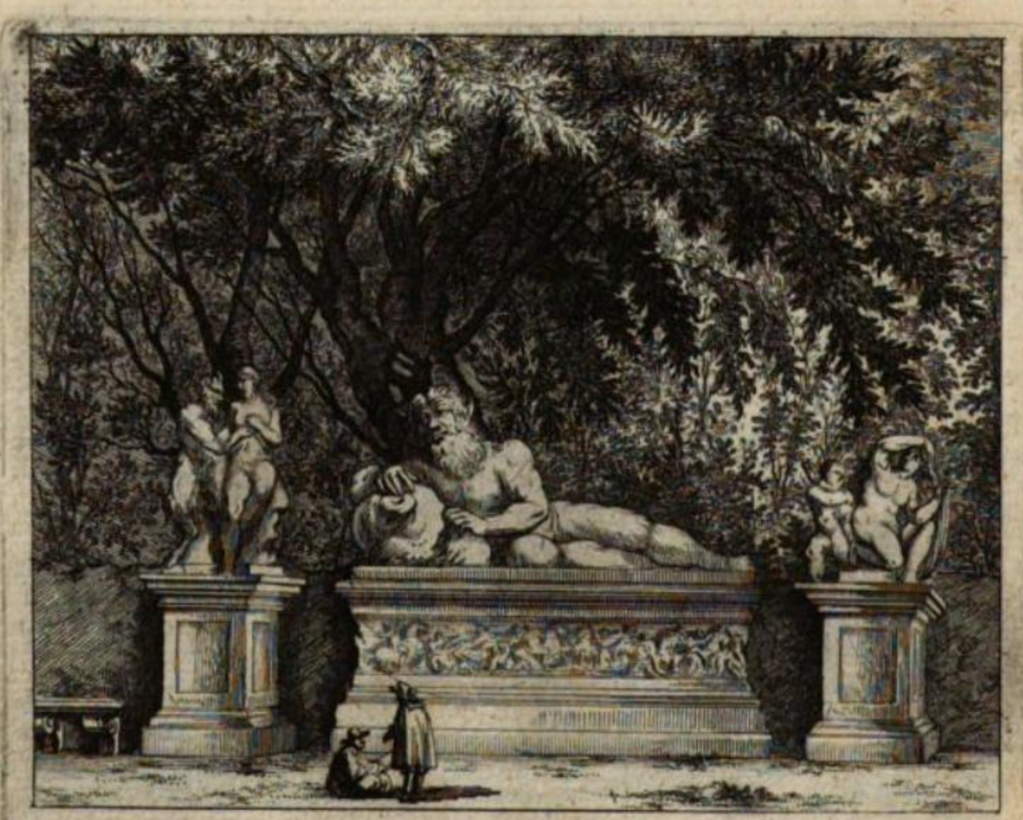

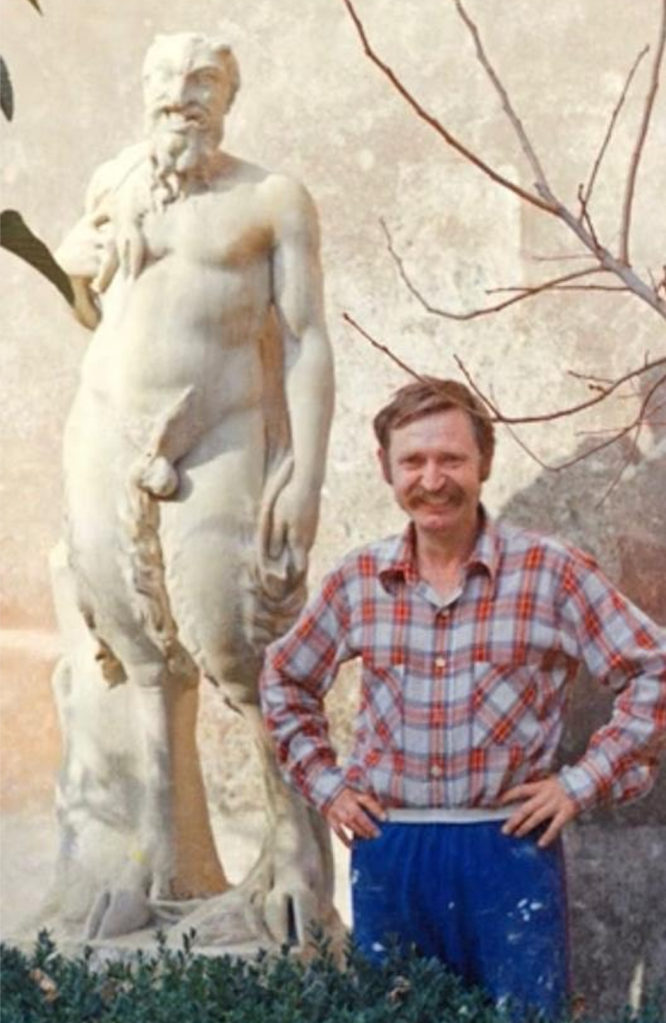

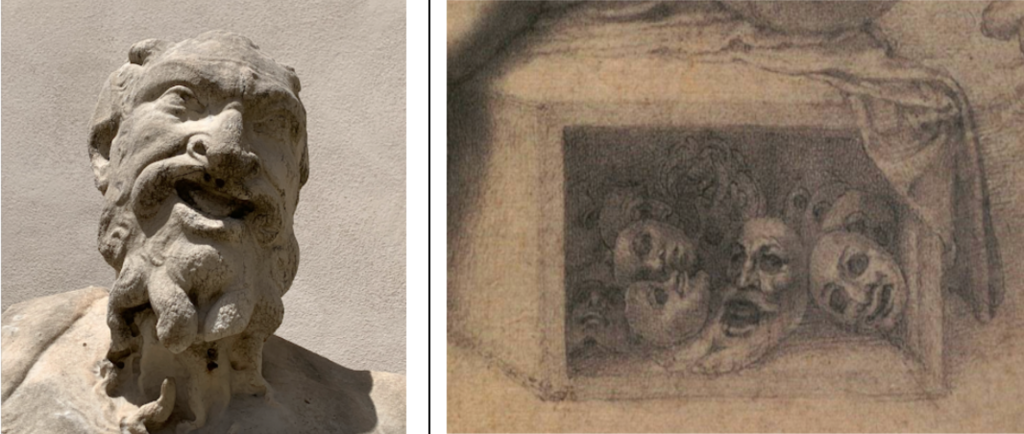

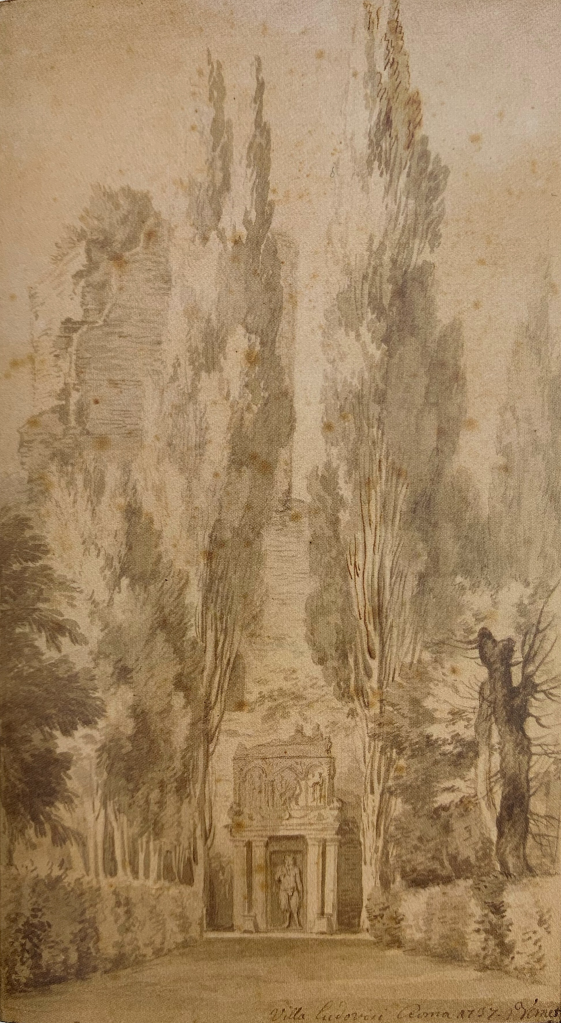

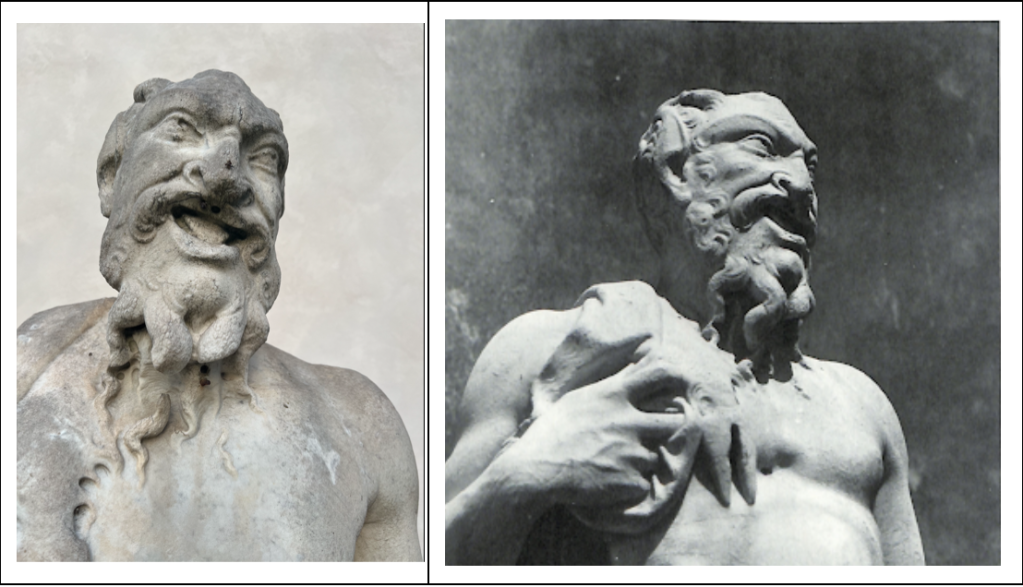

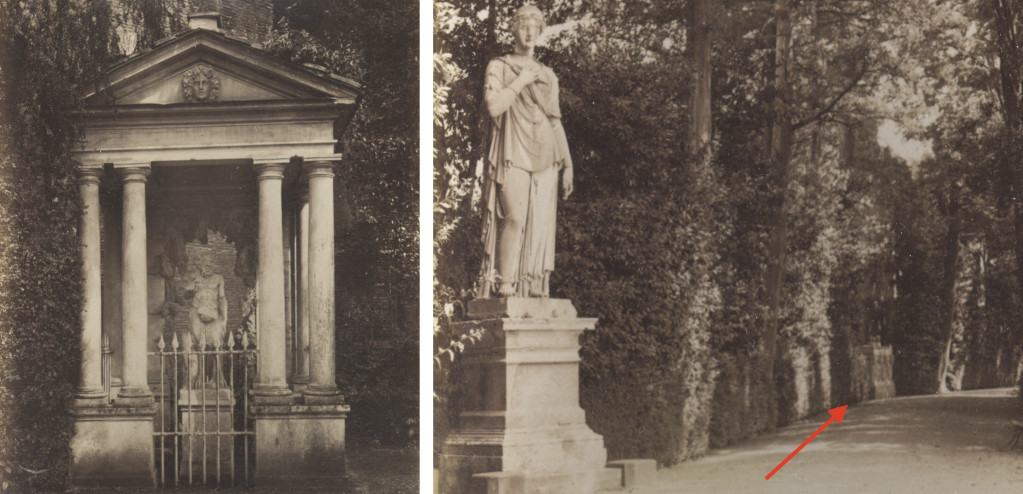

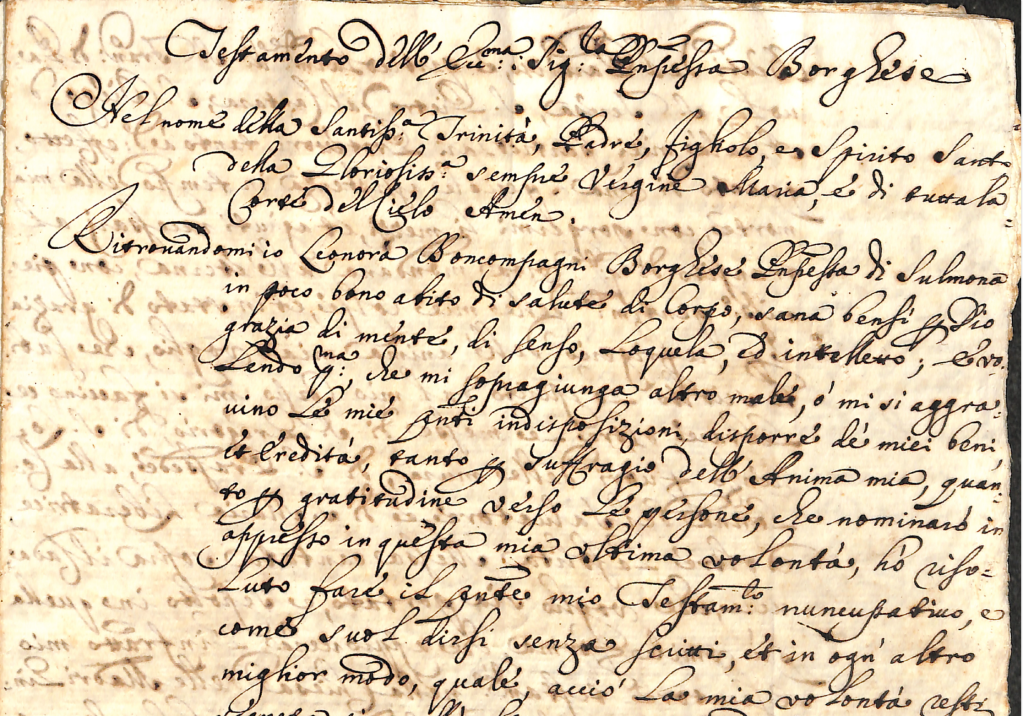

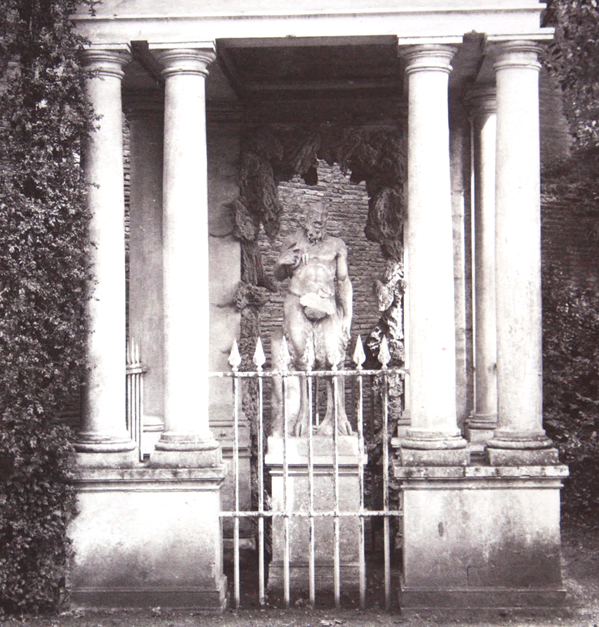

The Ludovisi Pan in its (post-1800) aedicula, Villa Ludovisi, 1885. Collection HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

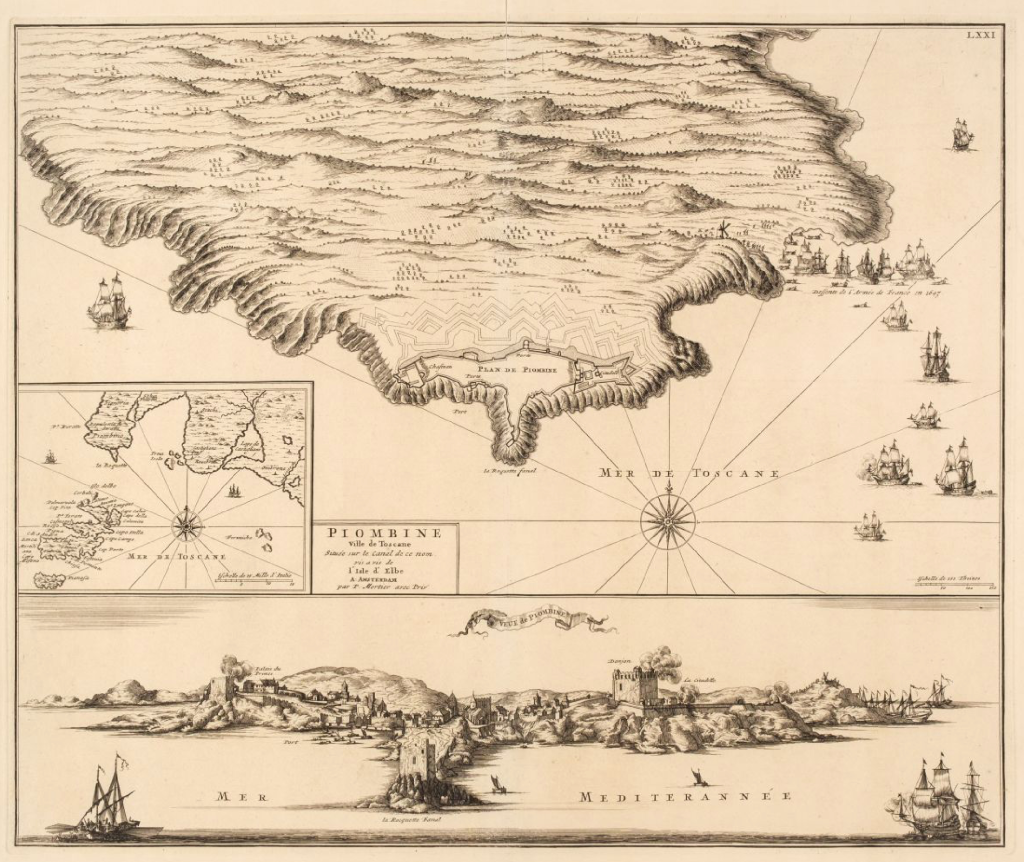

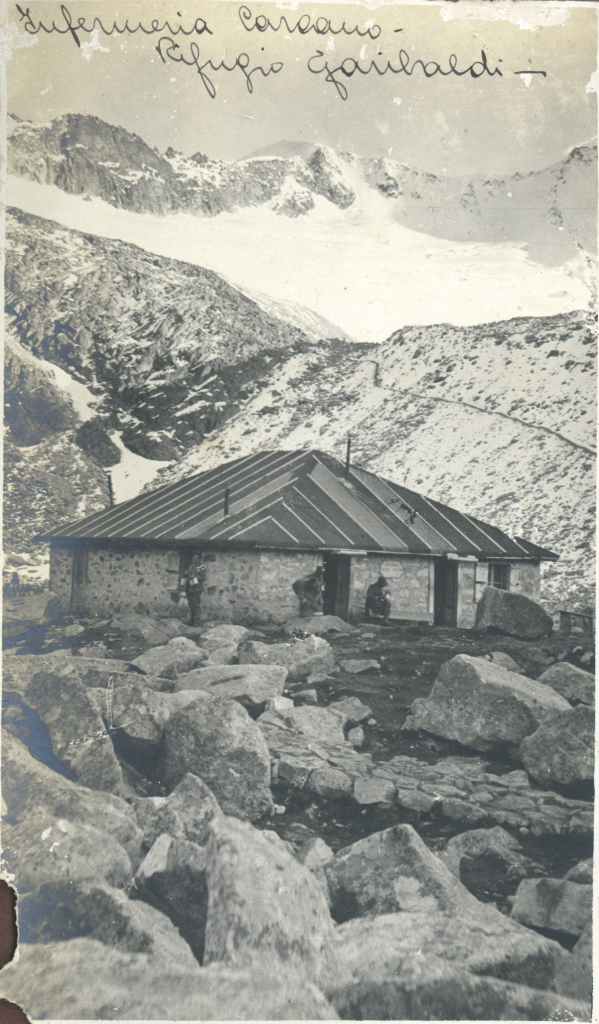

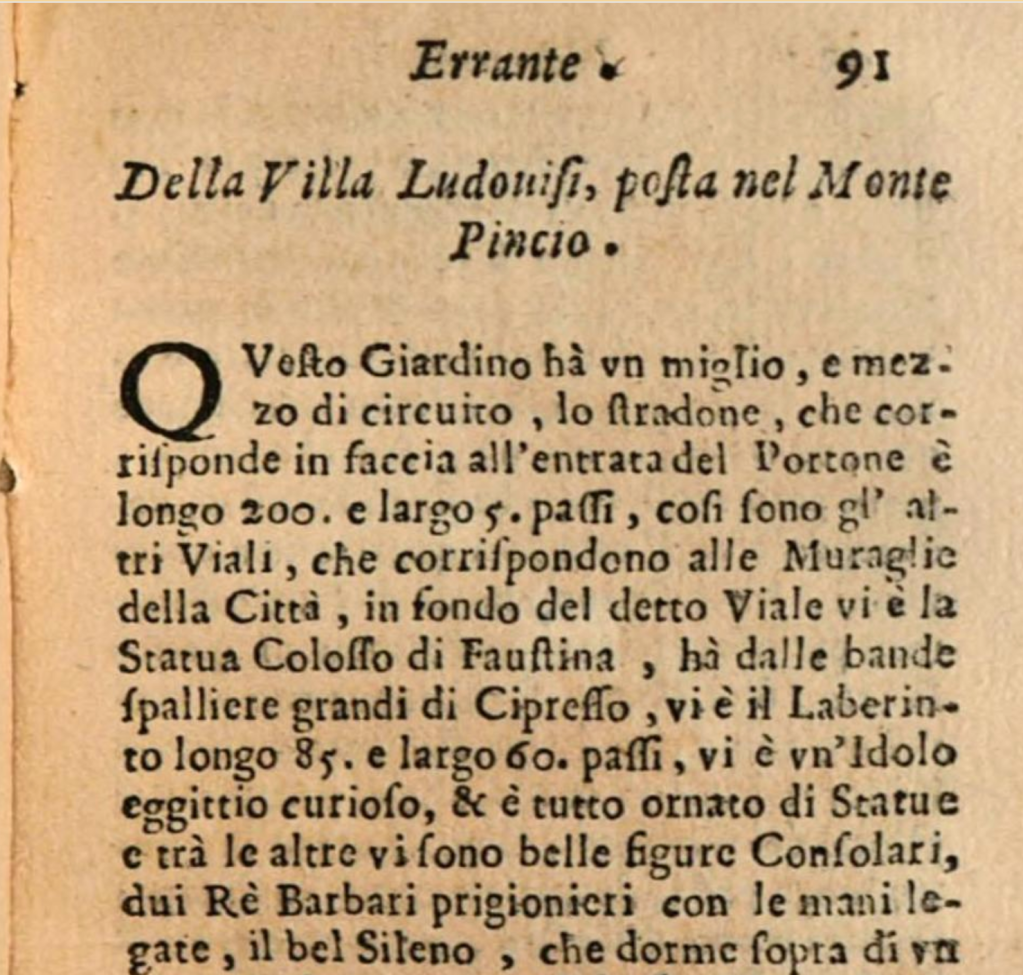

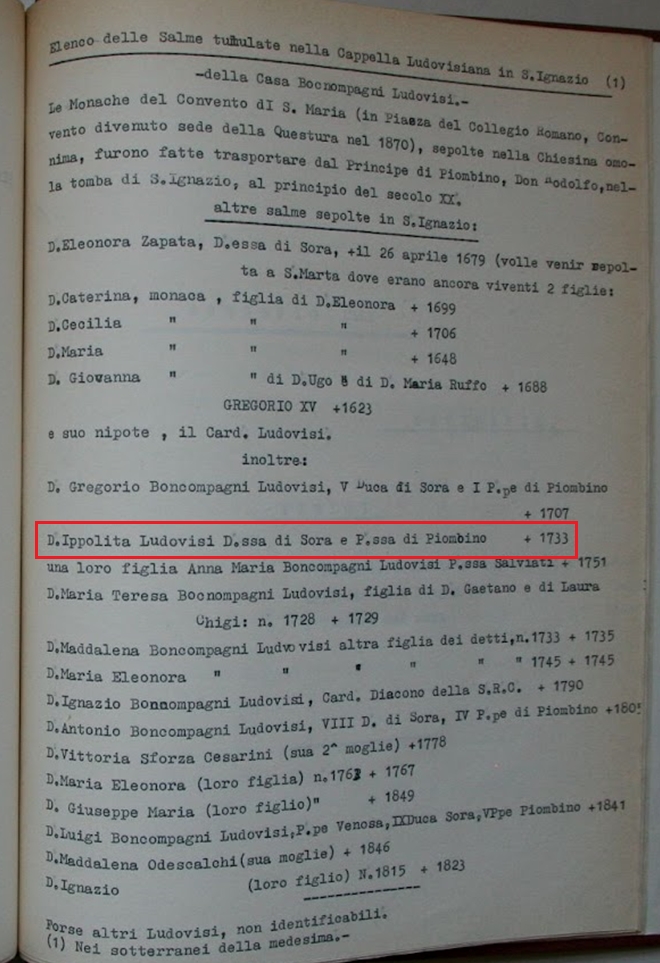

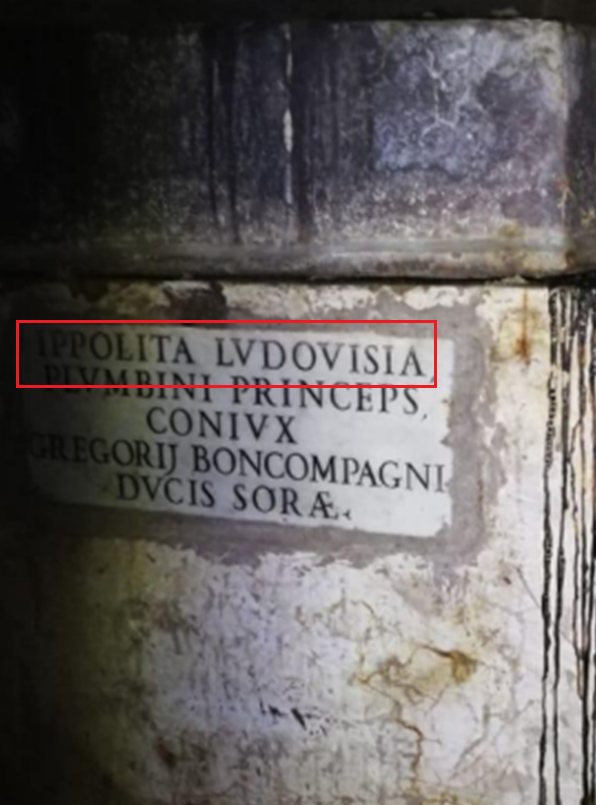

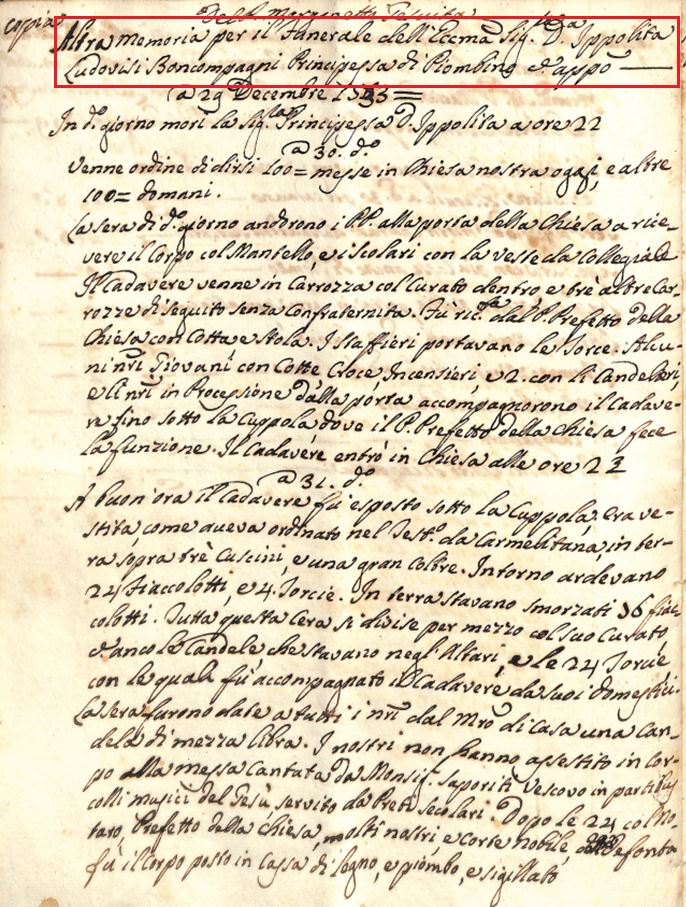

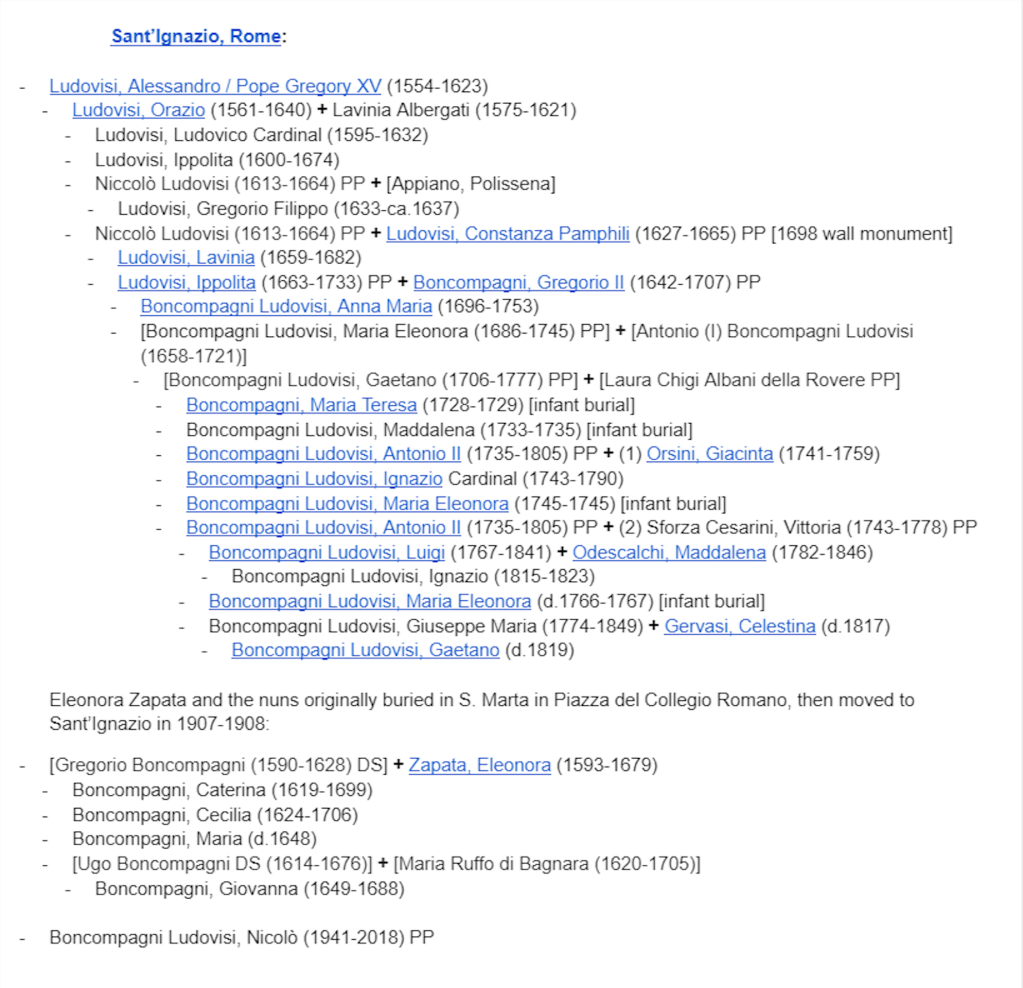

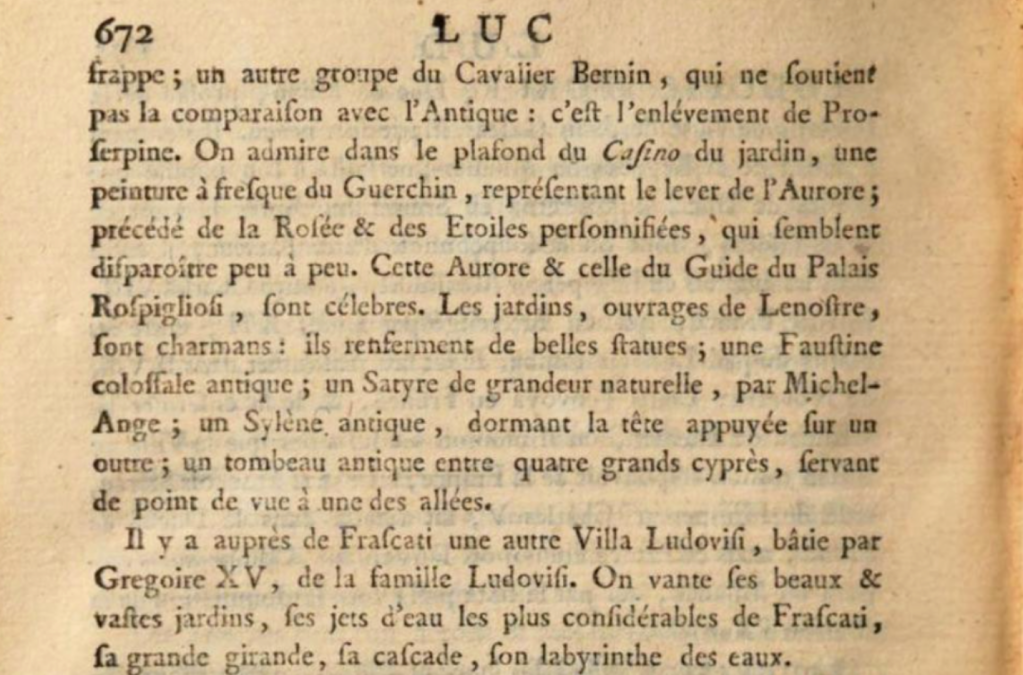

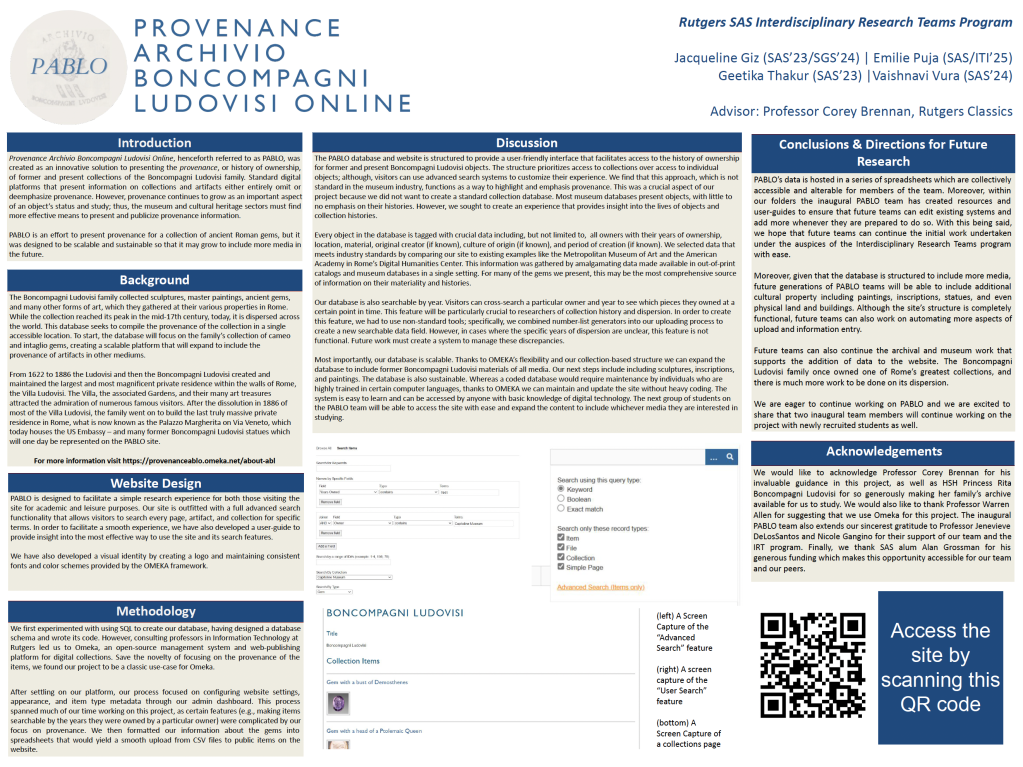

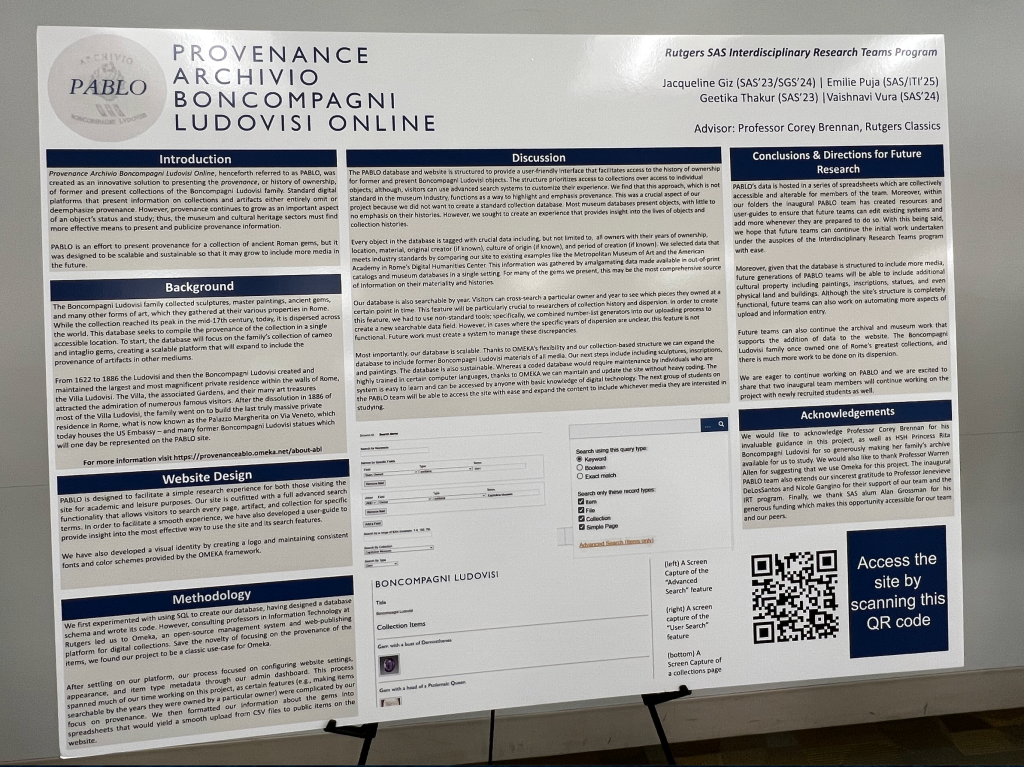

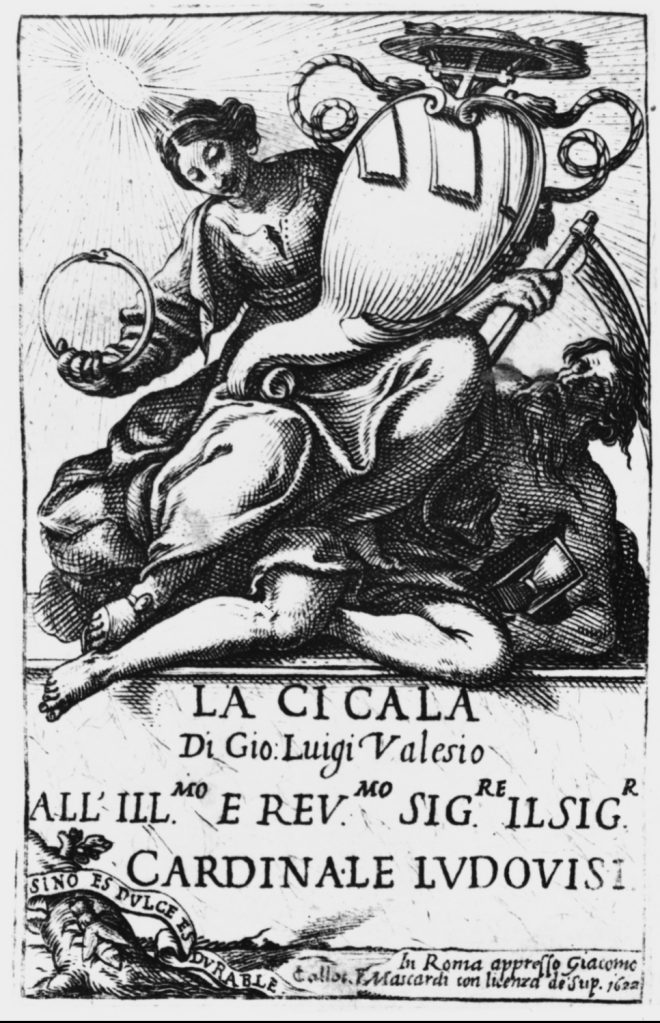

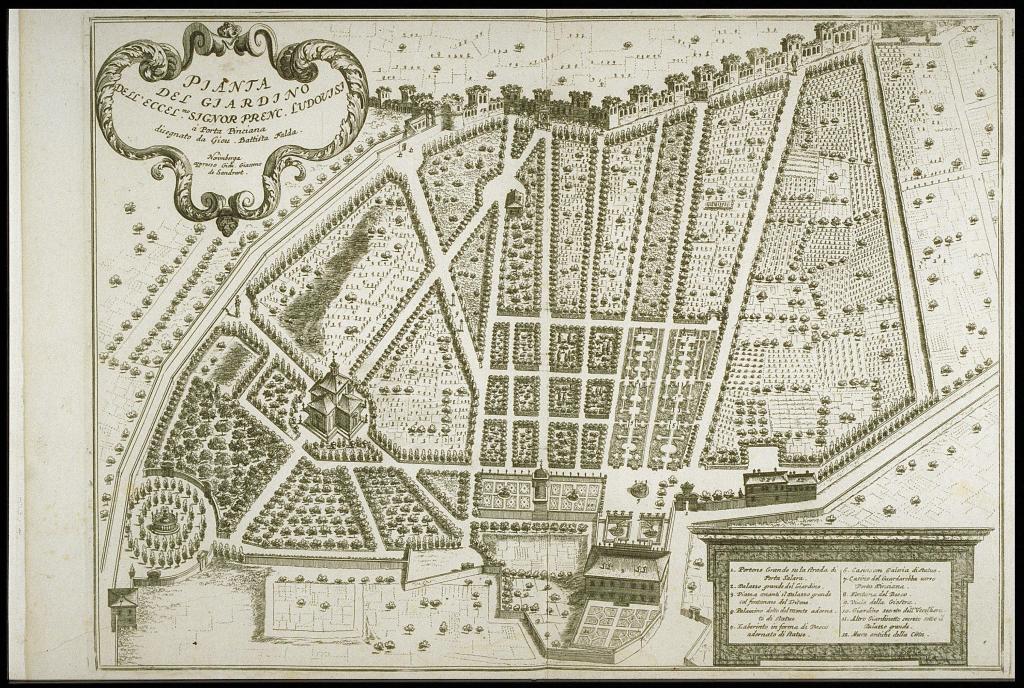

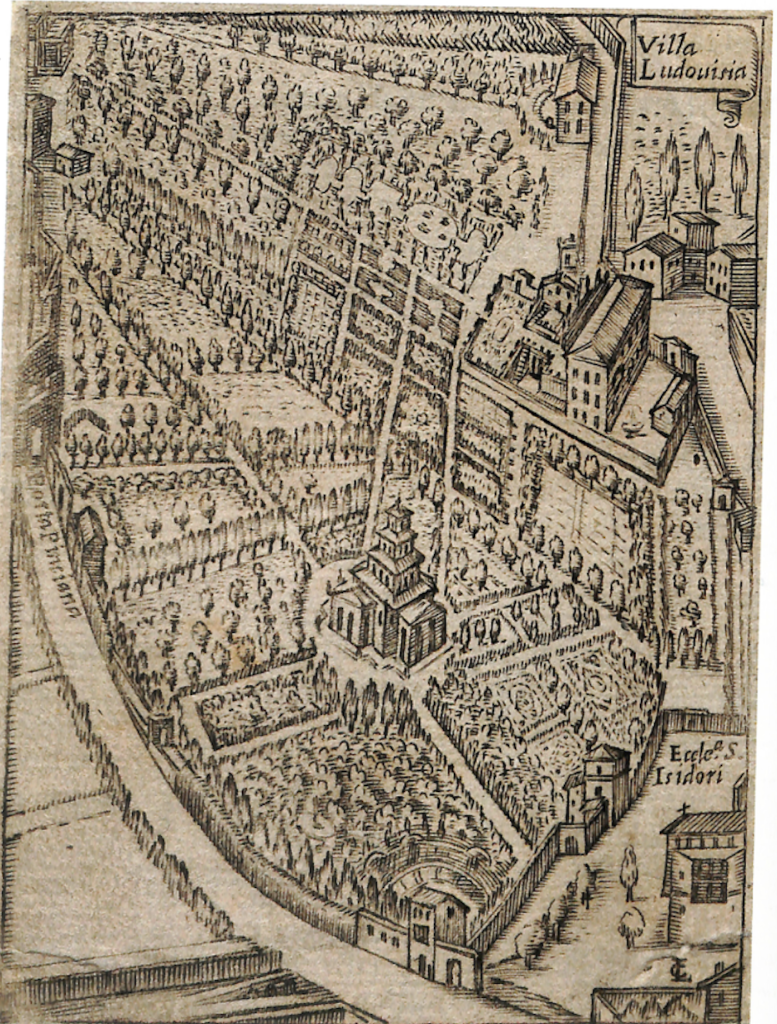

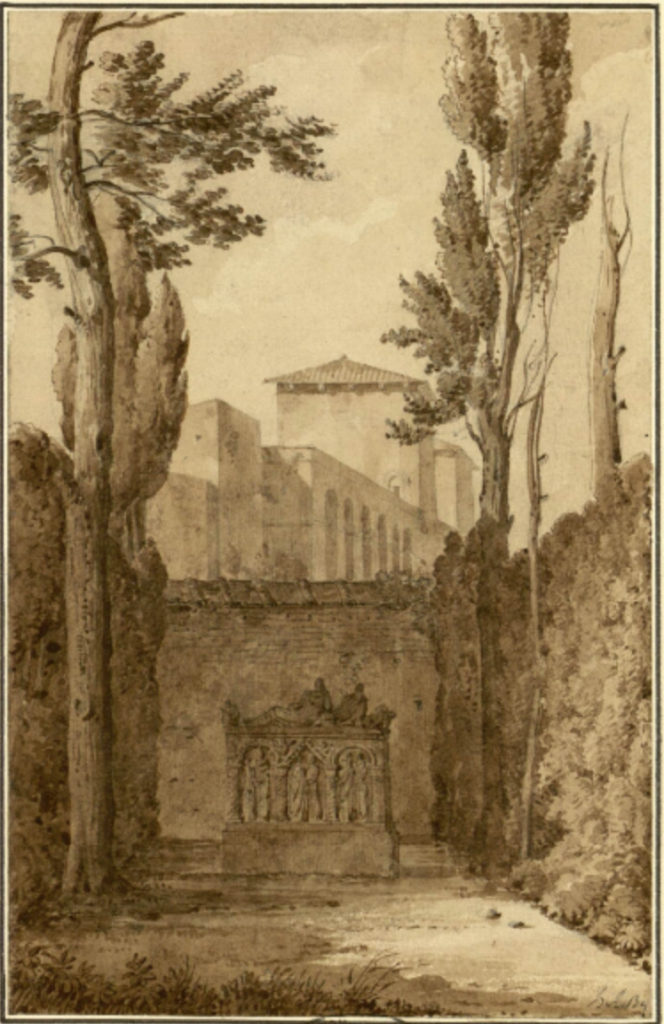

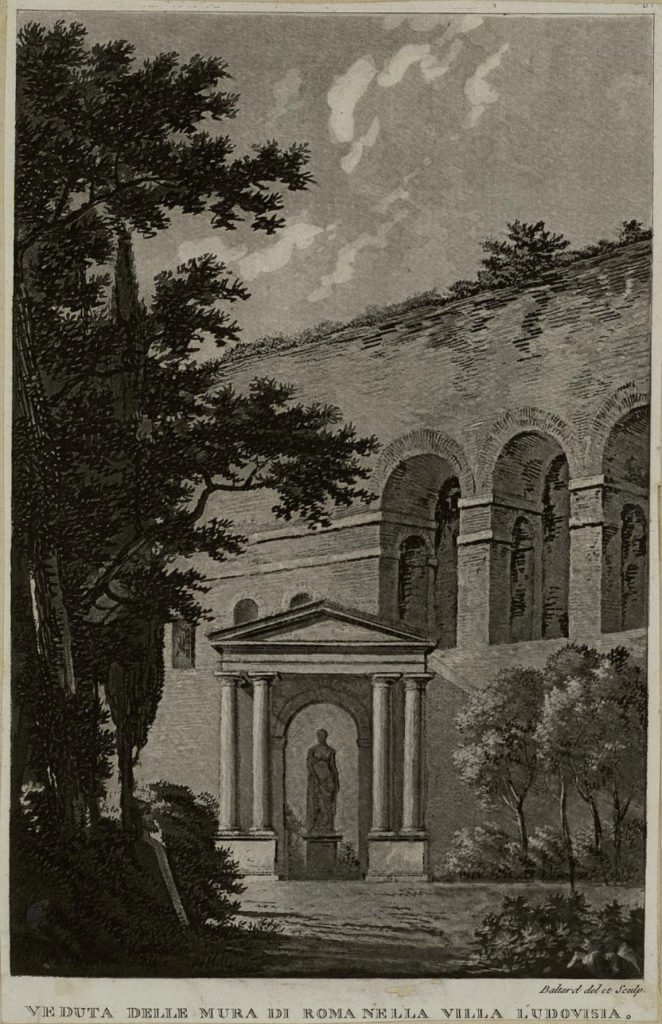

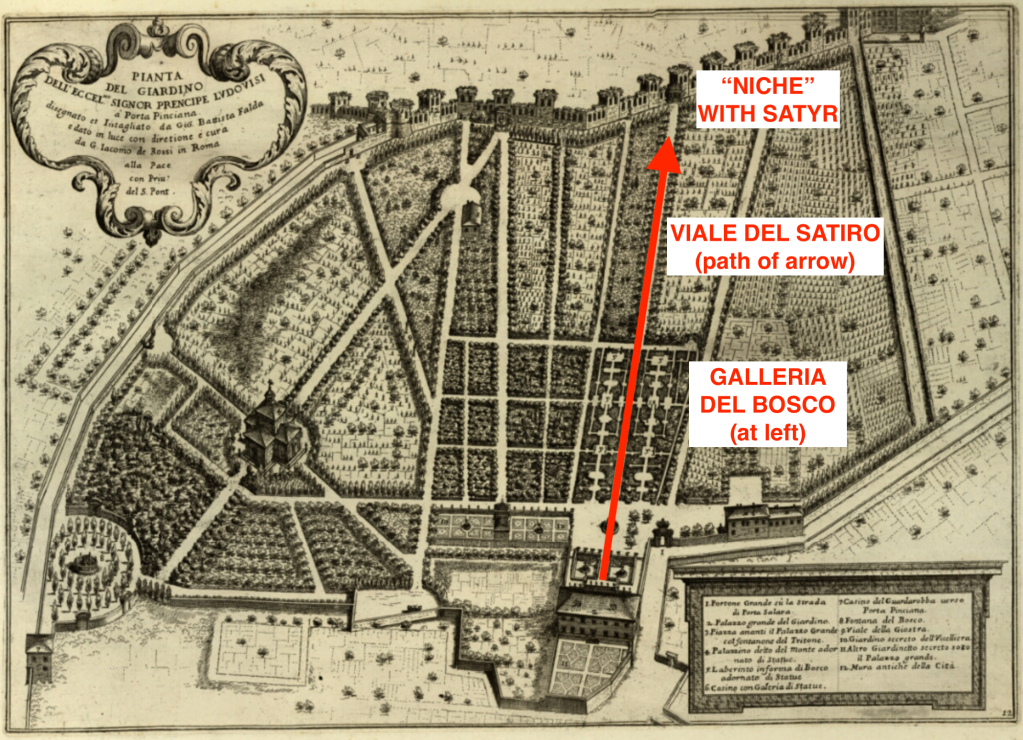

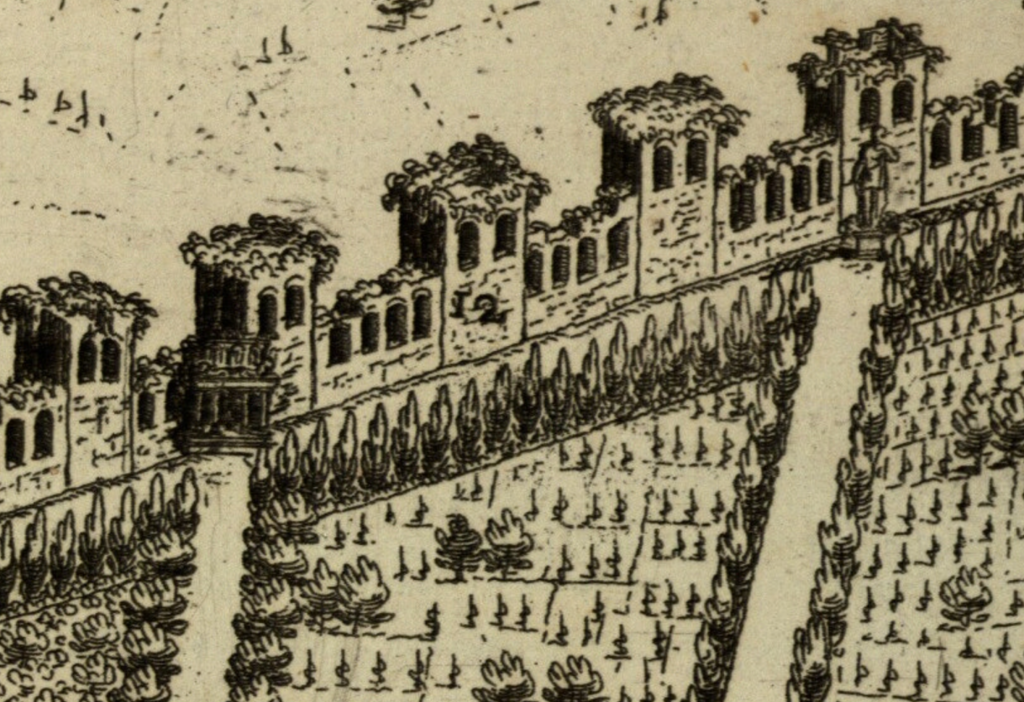

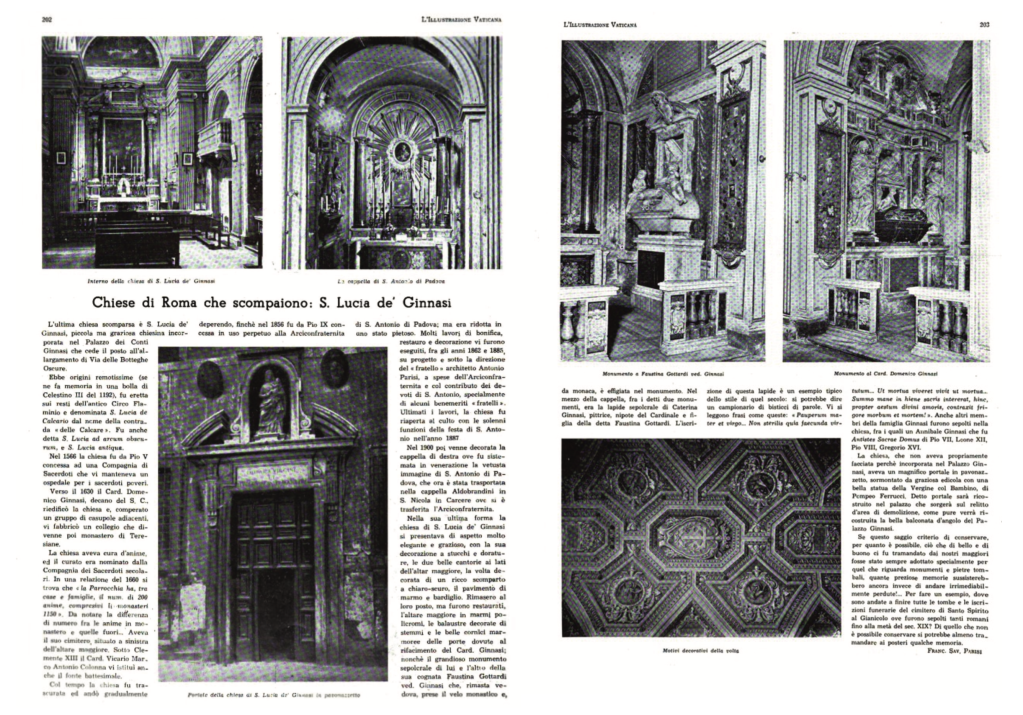

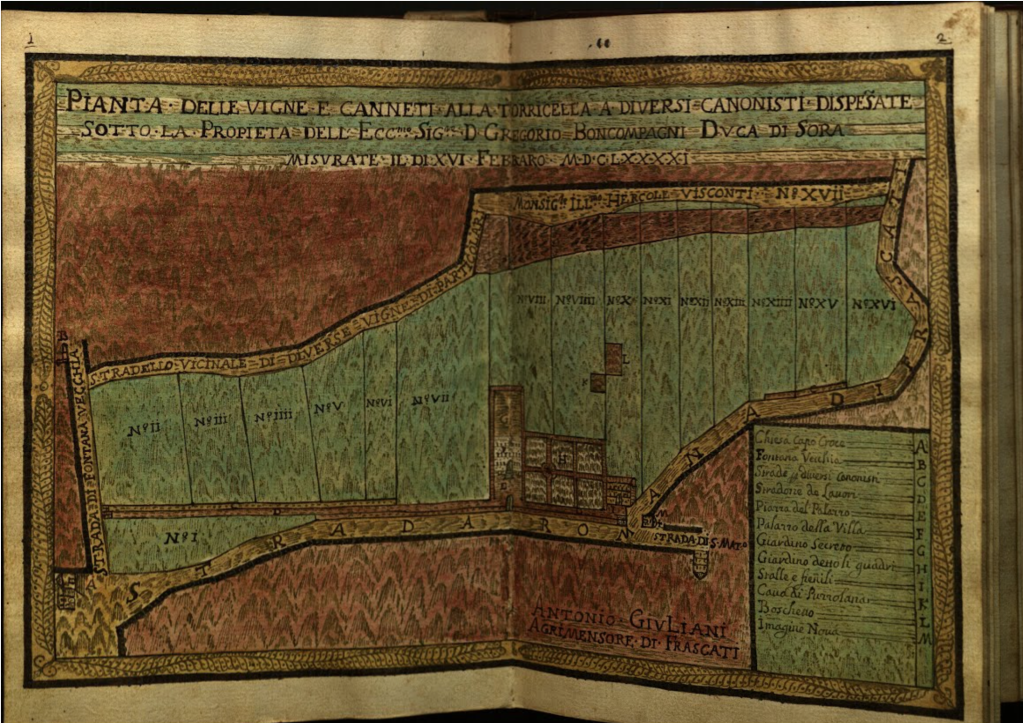

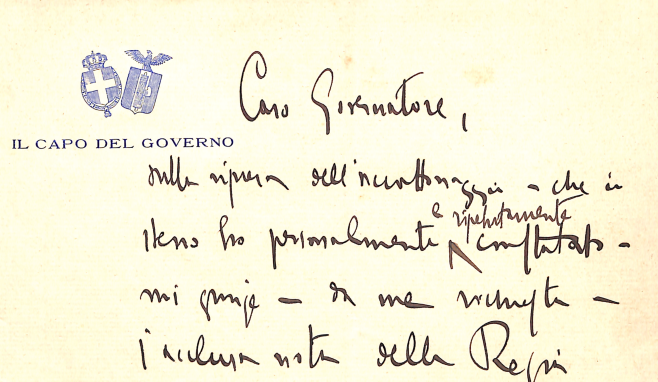

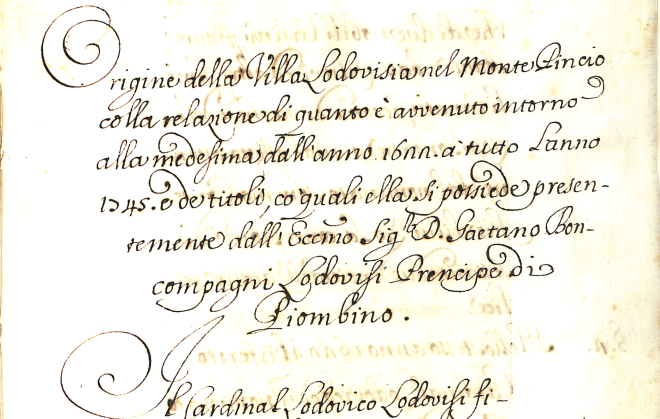

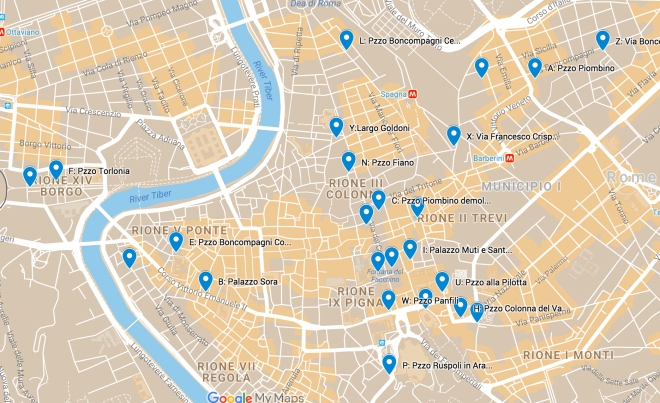

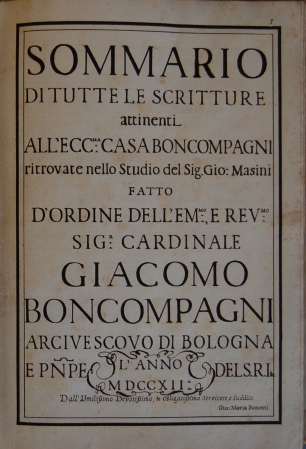

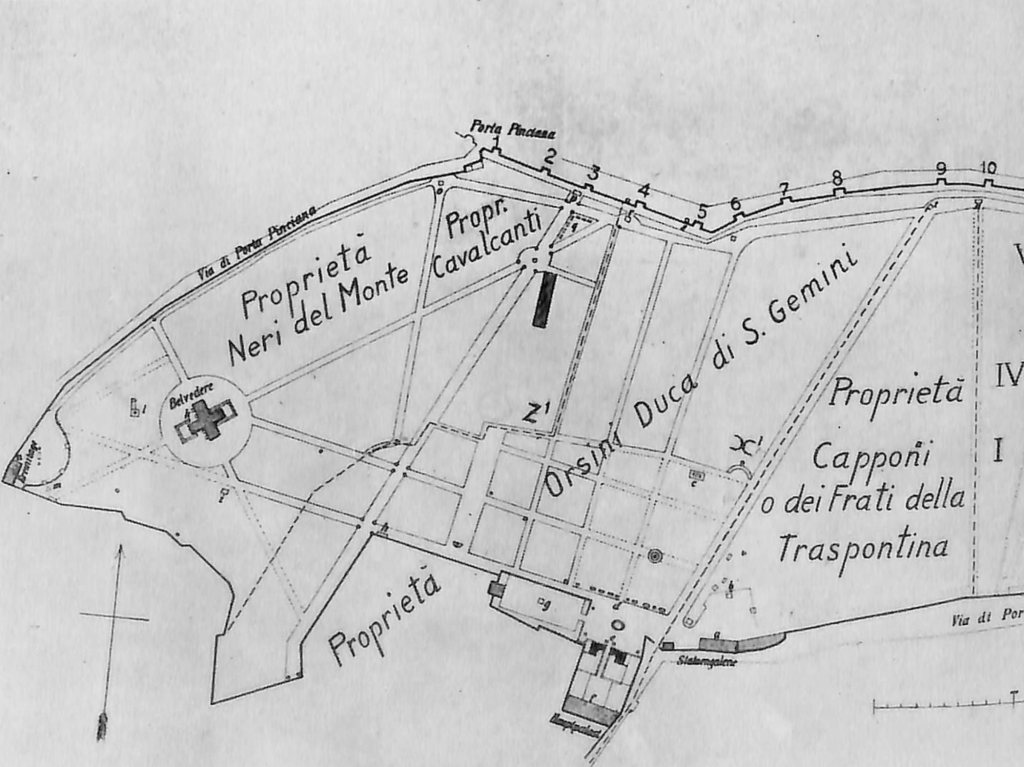

Starting in June 1621 and into early 1622, a papal nephew, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, bought several adjacent properties on the Pincio hill to form a “Villa Ludovisi”. All these contiguous estates were within the Aurelian Walls, on the site of the ancient Gardens of Sallust.

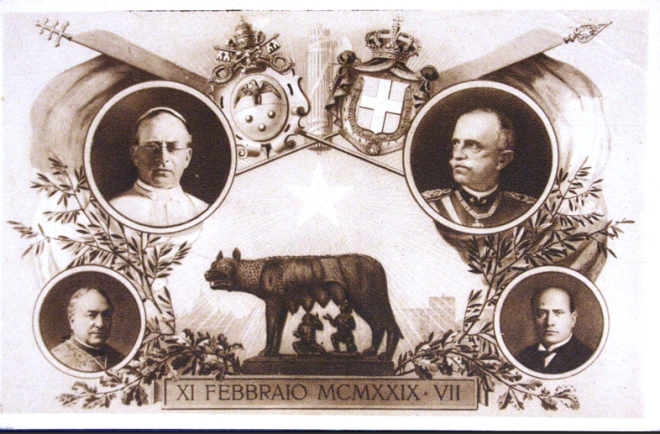

The Cardinal moved with remarkable speed in developing his purchases, evidently fearing that his sickly uncle, Gregory XV Ludovisi, was not long for the world. The Pope in fact succumbed in July 1623, after just 29 months on the throne.

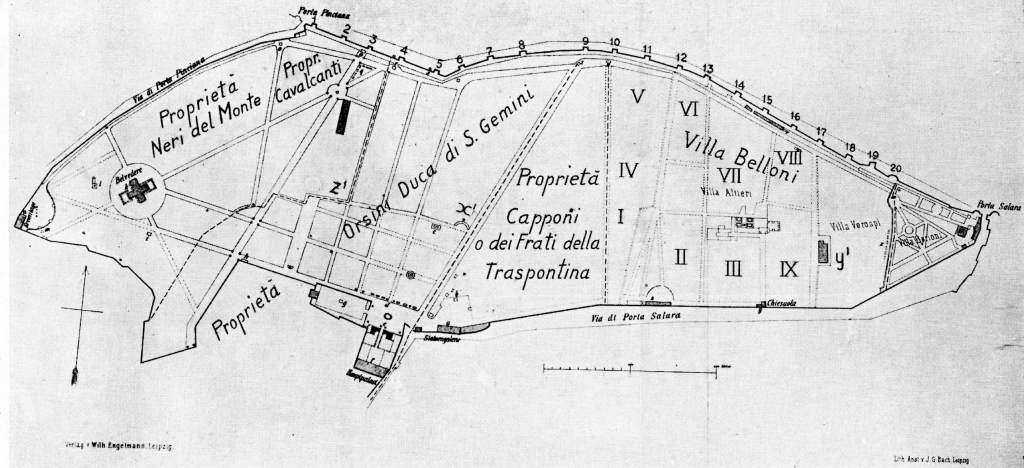

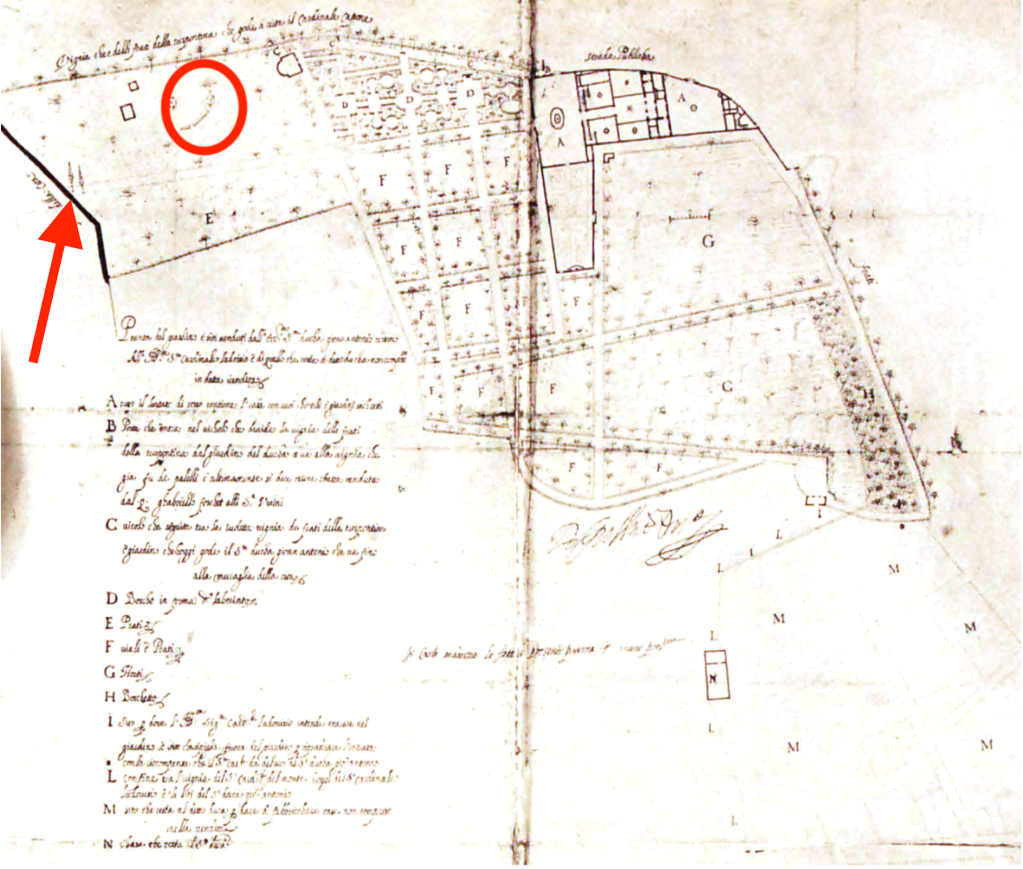

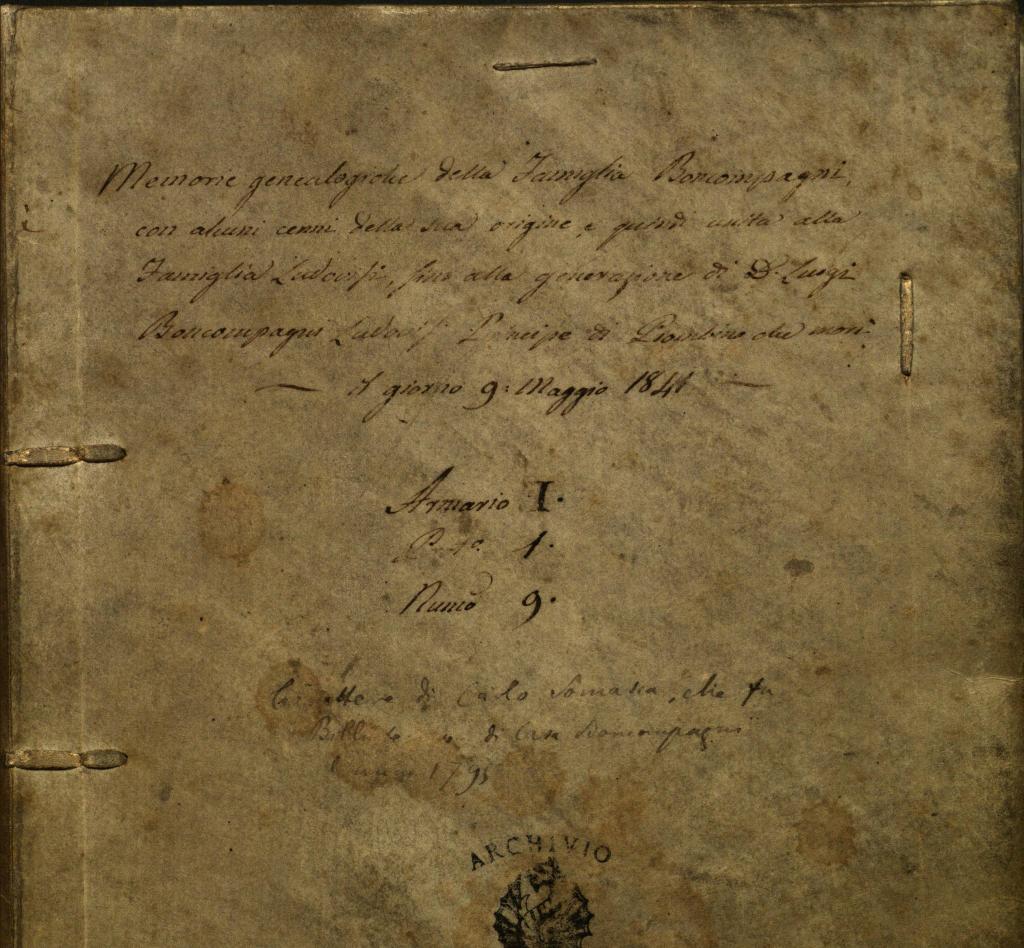

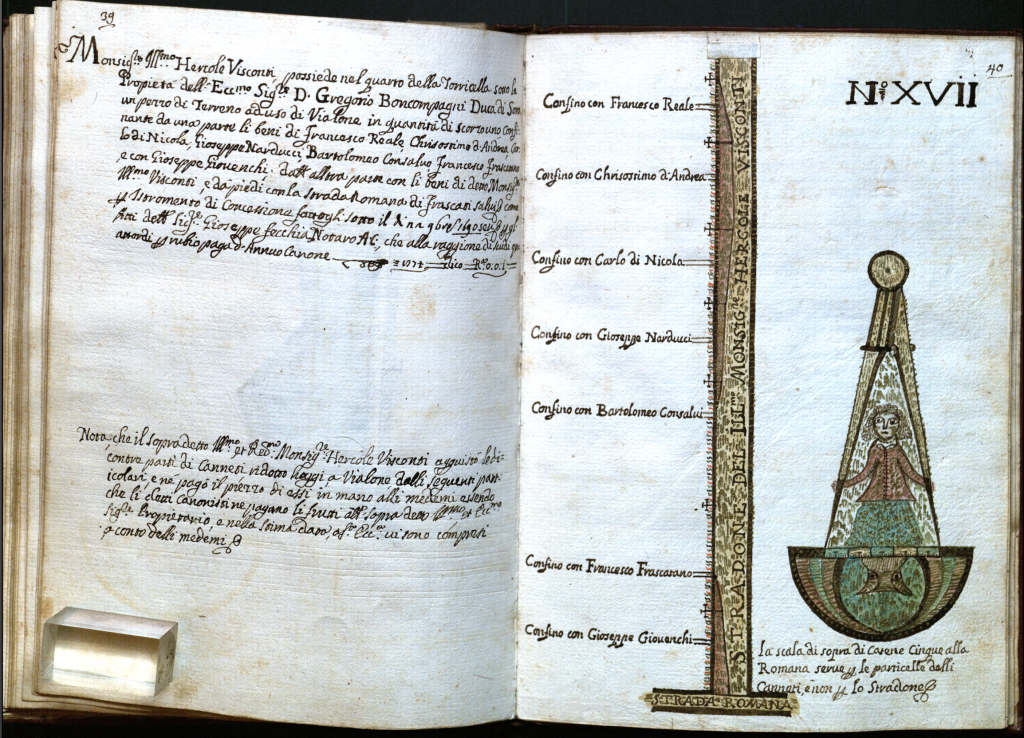

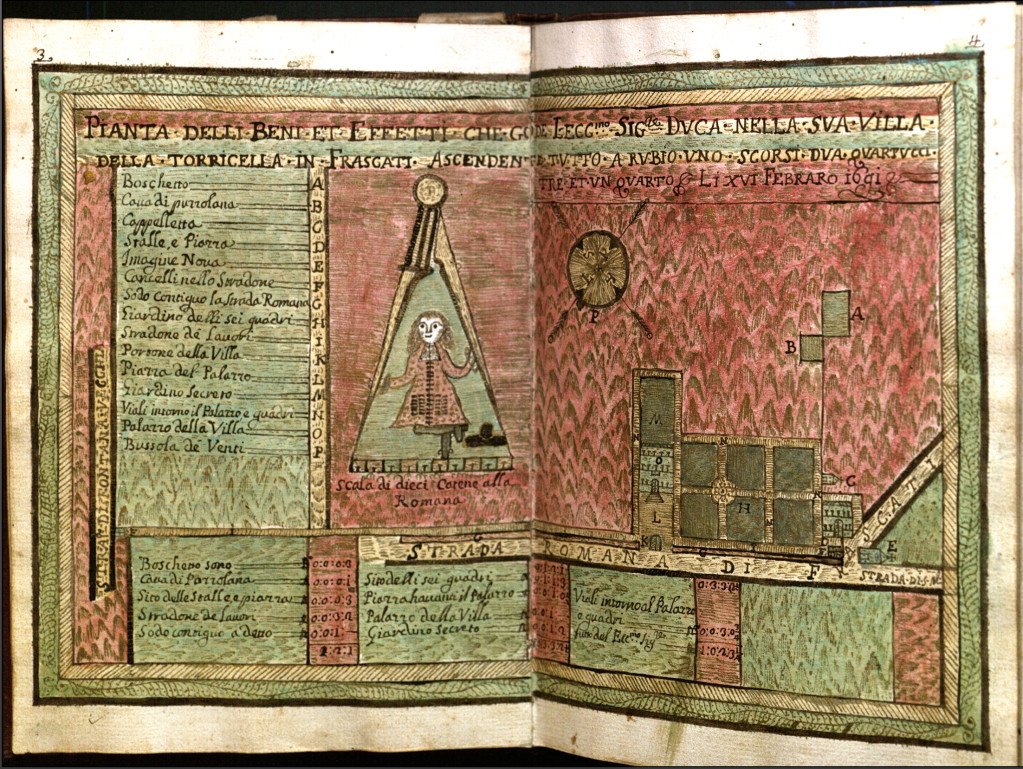

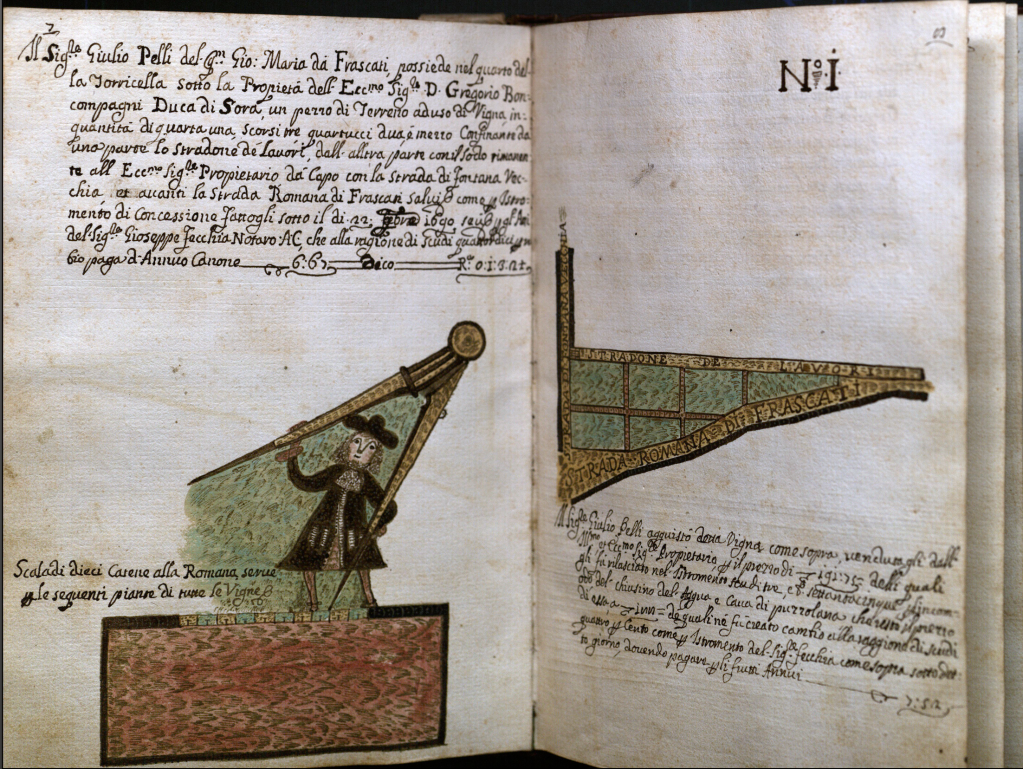

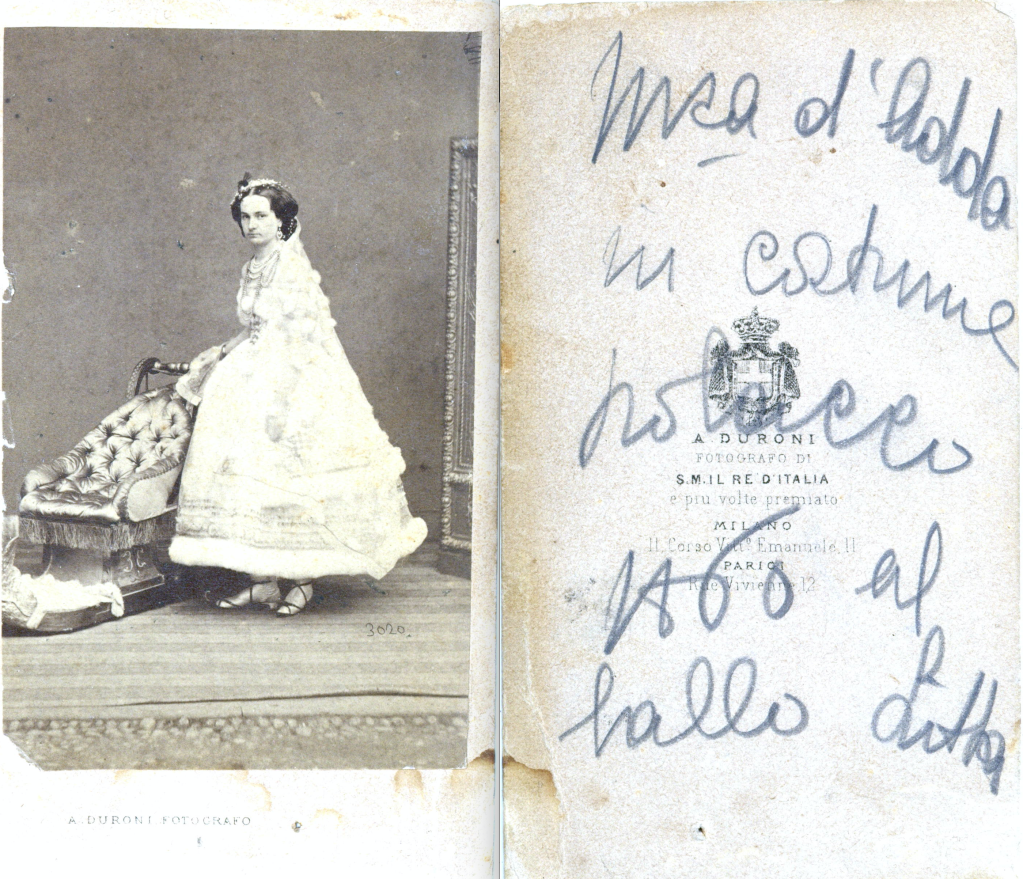

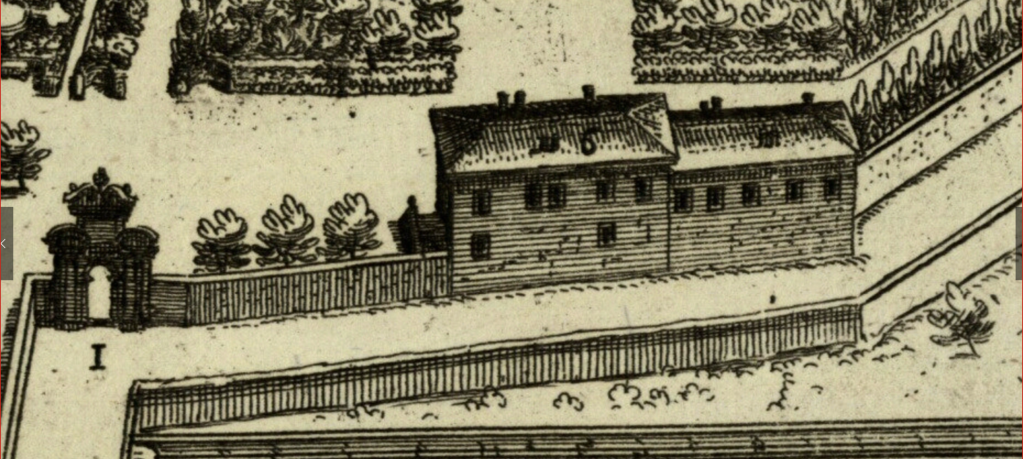

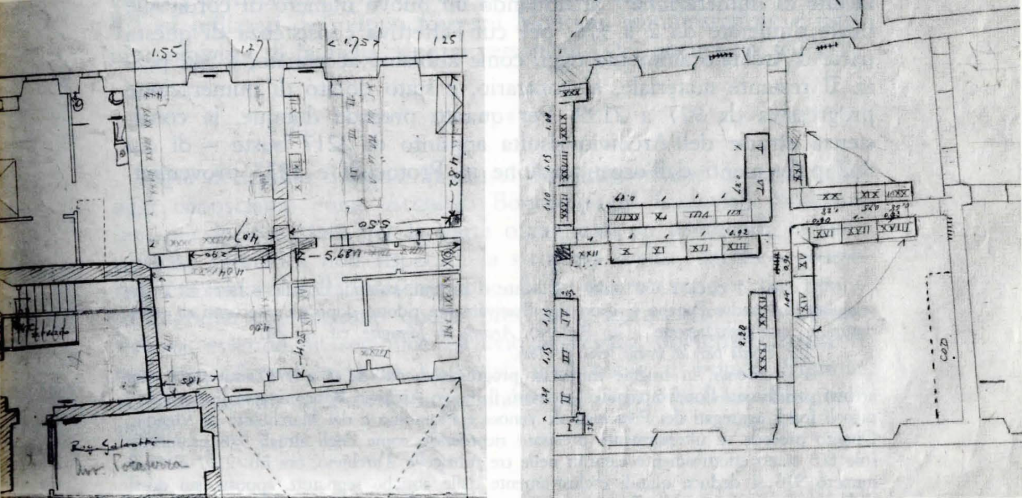

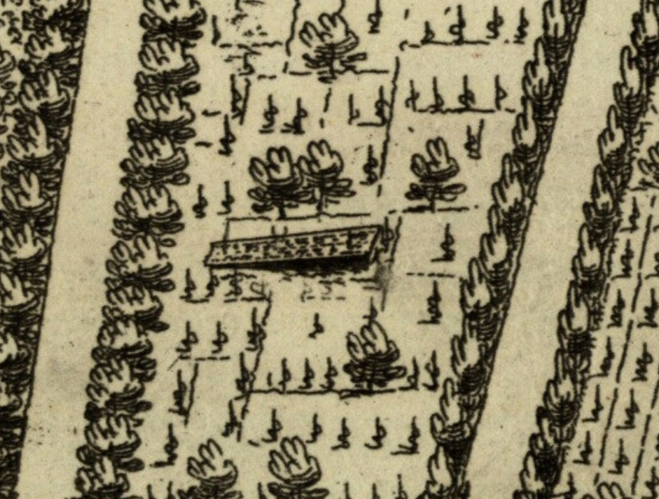

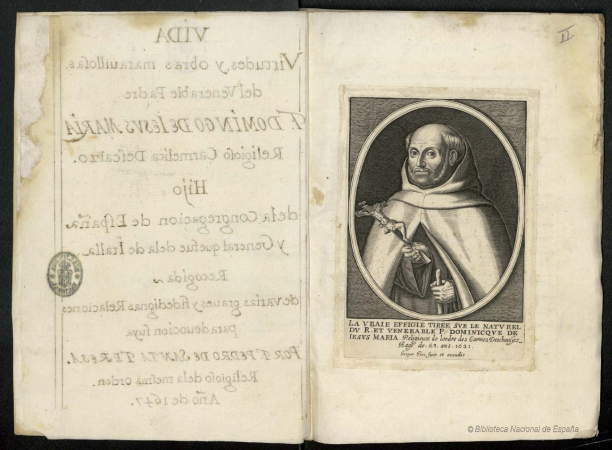

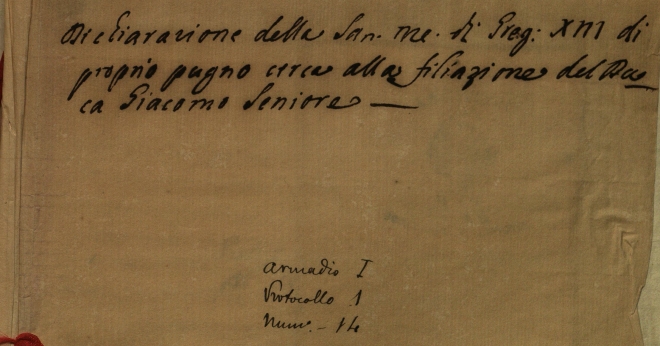

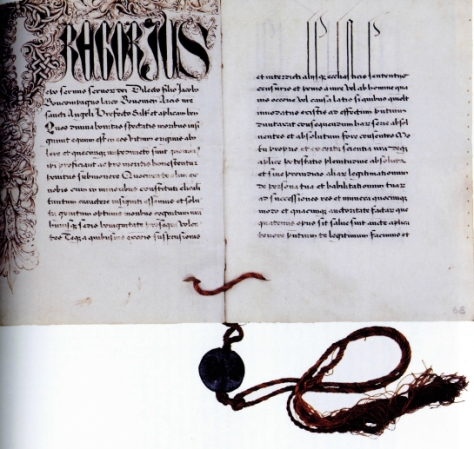

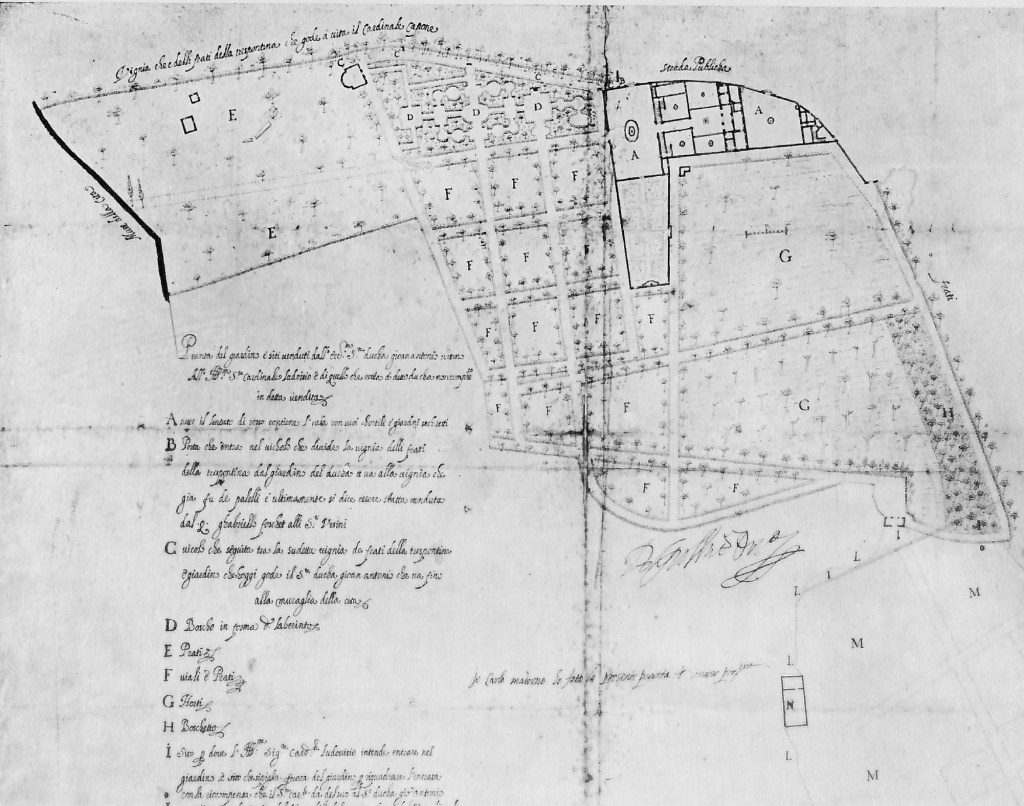

Map by Carlo Maderno (early 1622) of Orsini property on the Pincio hill in Rome, drawn in connection to the sale of the property to Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi = Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 611 no. 5. From G. Felici, Villa Ludovisi in Roma (1952).

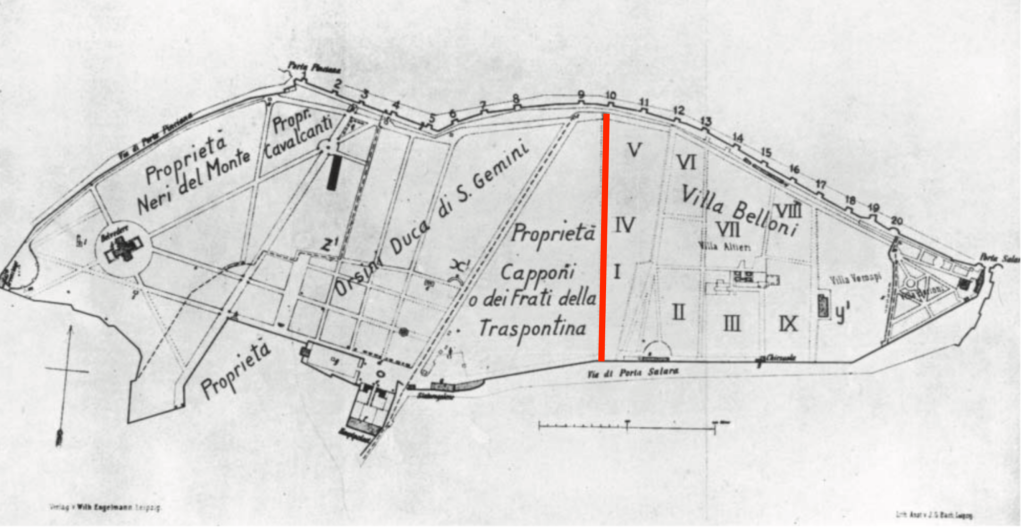

Three estates formed the core of the original Villa Ludovisi.

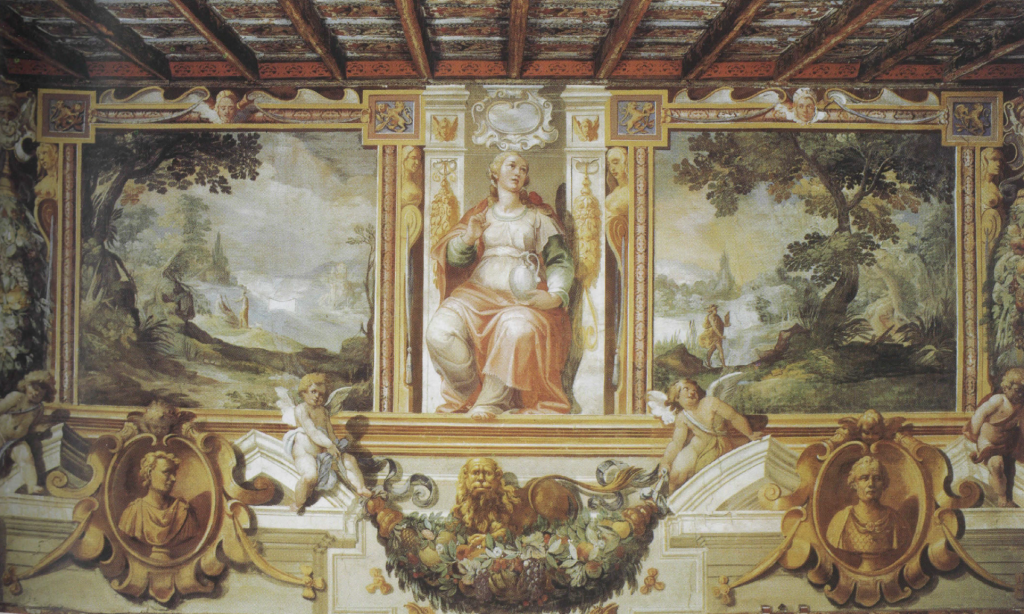

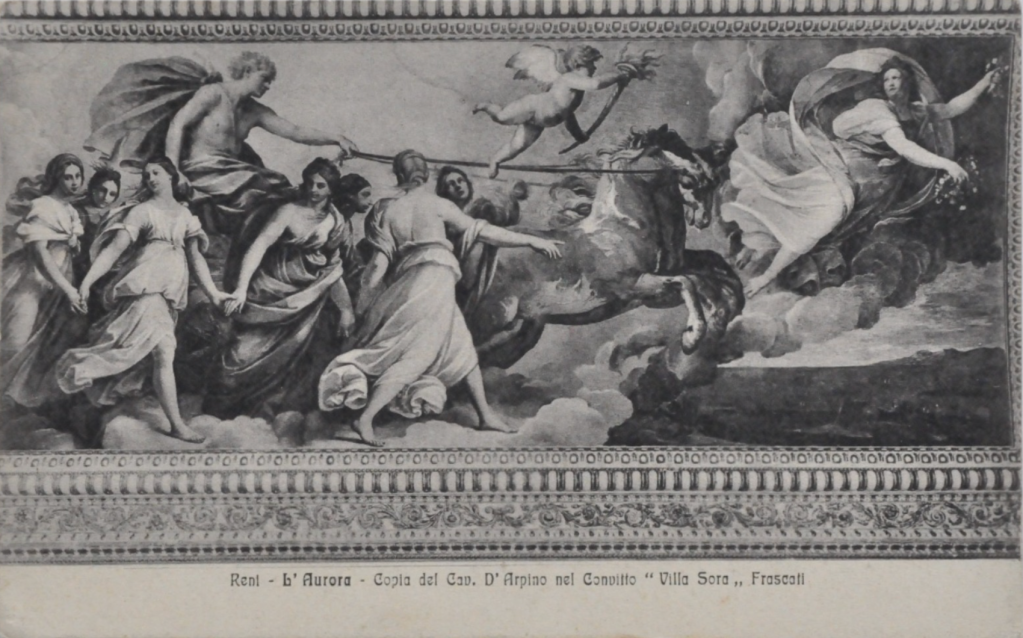

One had belonged to Cardinal Francesco del Monte, the early patron of Caravaggio, with what is now known as the Casino dell’Aurora at its center.

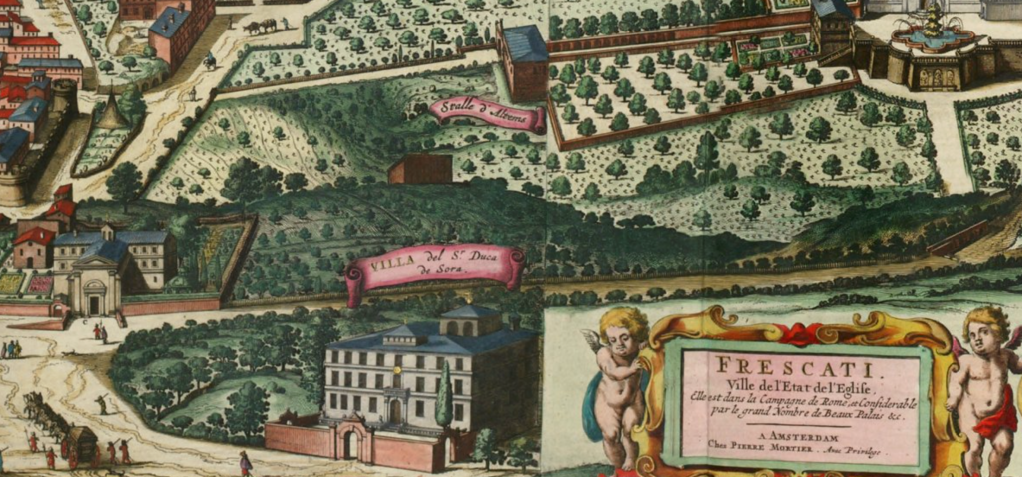

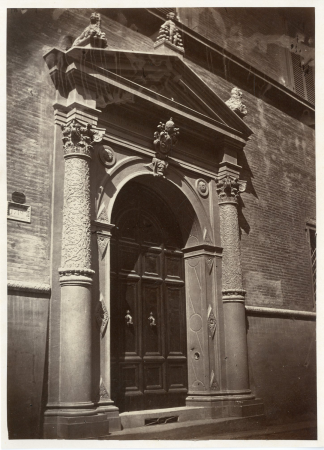

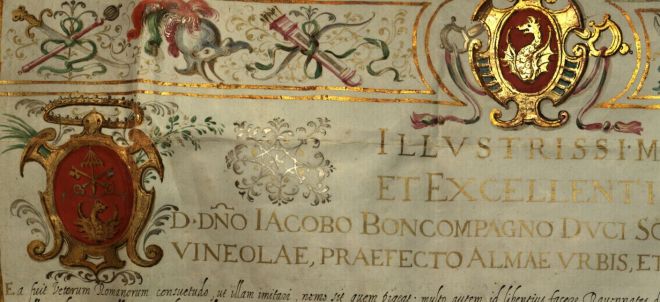

Another directly to its east was developed in the mid sixteenth century by a factious bishop of Pavia, Giovangirolamo De Rossi, which later had passed to the Orsini family of Gravina. The palace attached to that property today —with massive 19th and 20th century modifications—houses the US Embassy in Rome.

And east of that was a property once owned by the Frati della Traspontina, named the Villa Capponi, whose main structure now functions (again, with considerable alterations) as a garage for US Embassy vehicles.

Map (from T. Schreiber, Die antiken Bildwerke der Villa Ludovisi in Rom [1880], with annotations by G. Felici, Villa Ludovisi in Roma [1952]) of the Villa Ludovisi as it stood 1622-1825.

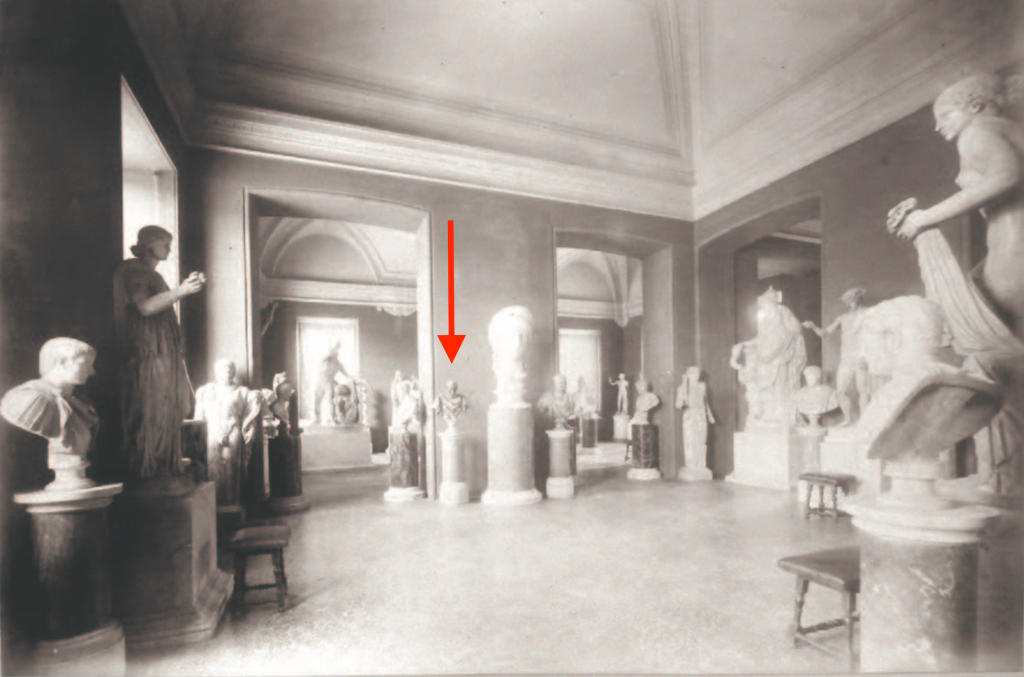

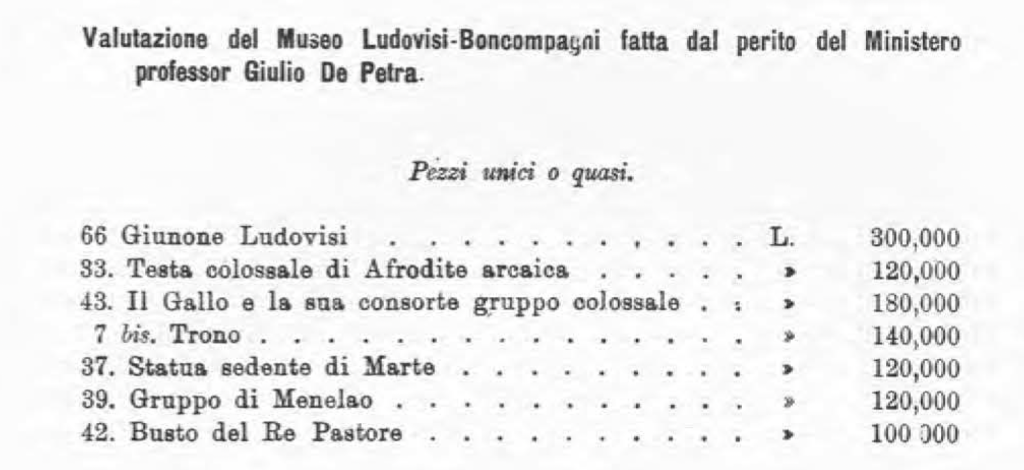

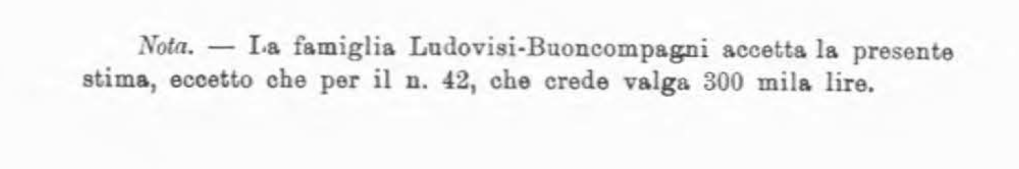

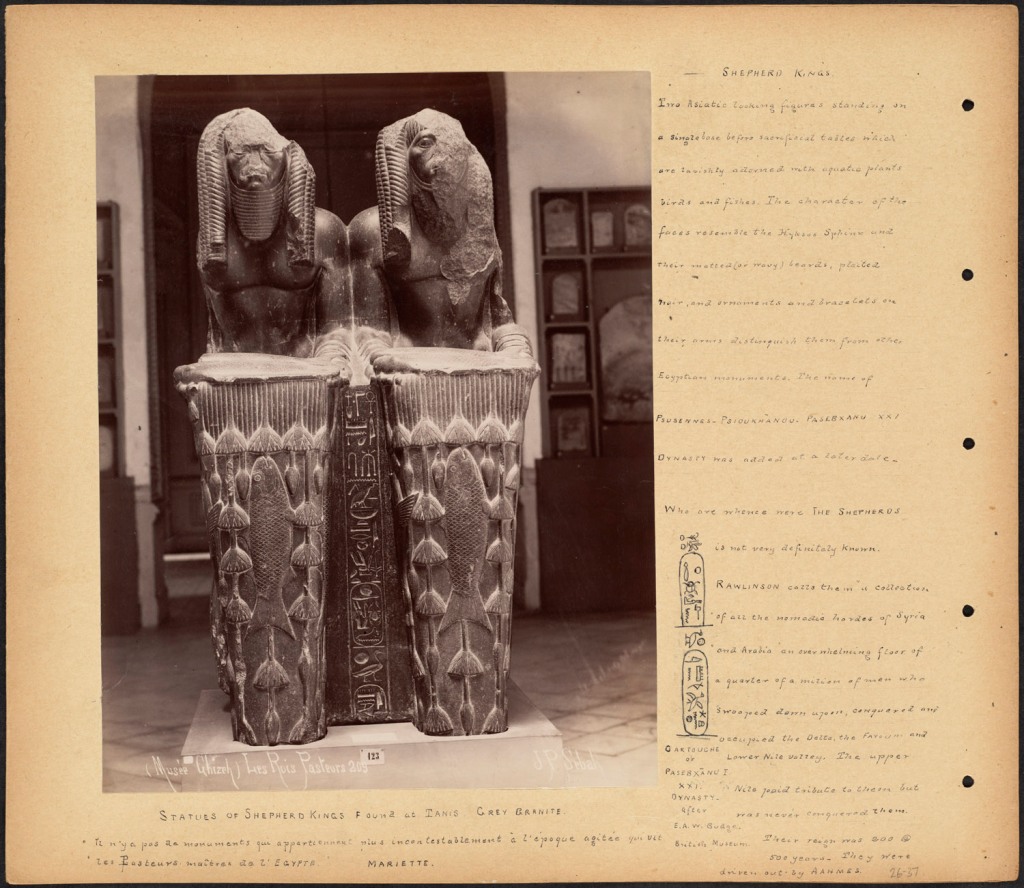

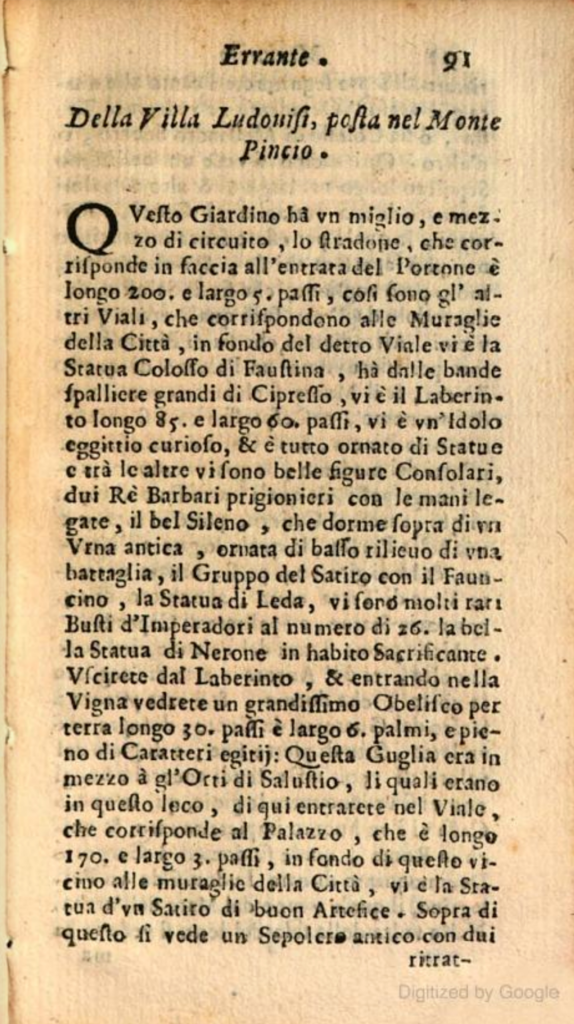

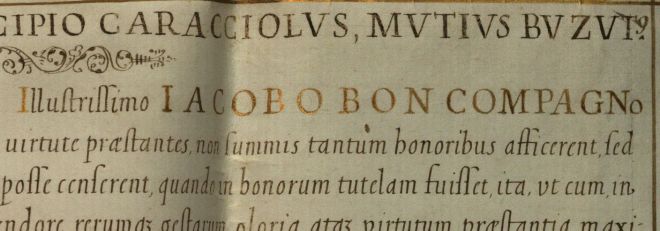

For his new spread, Cardinal Ludovisi quickly amassed a significant collection of well over 300 (mostly ancient) sculptures, a mindboggling assortment of important paintings, plus new mural work commissioned from star painters from his native Bologna and vicinity.

One might ask: where did all the antique sculptures come from? At least from the mid-18th century, it was commonly supposed that Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi himself excavated the bulk of them in the early 1620s when laying out his new Villa.

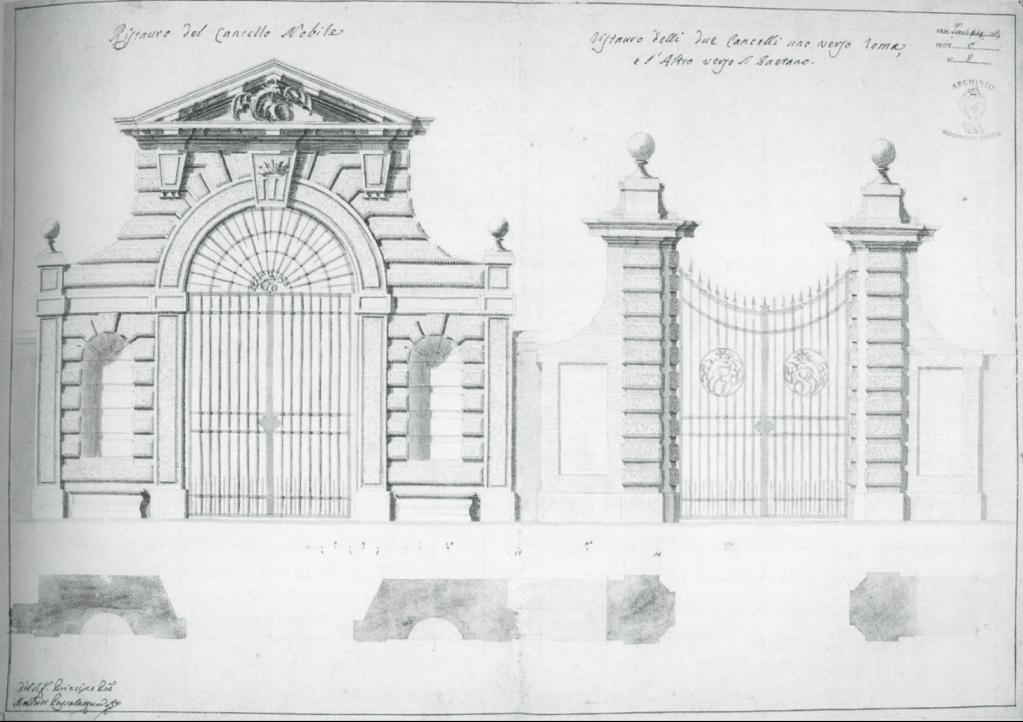

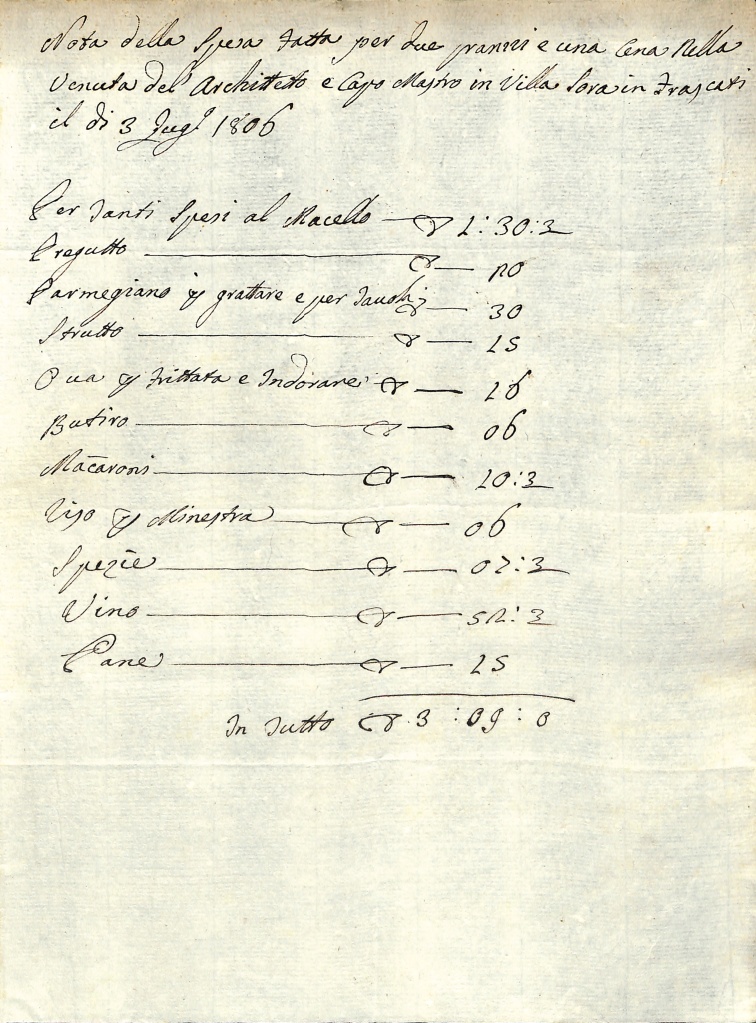

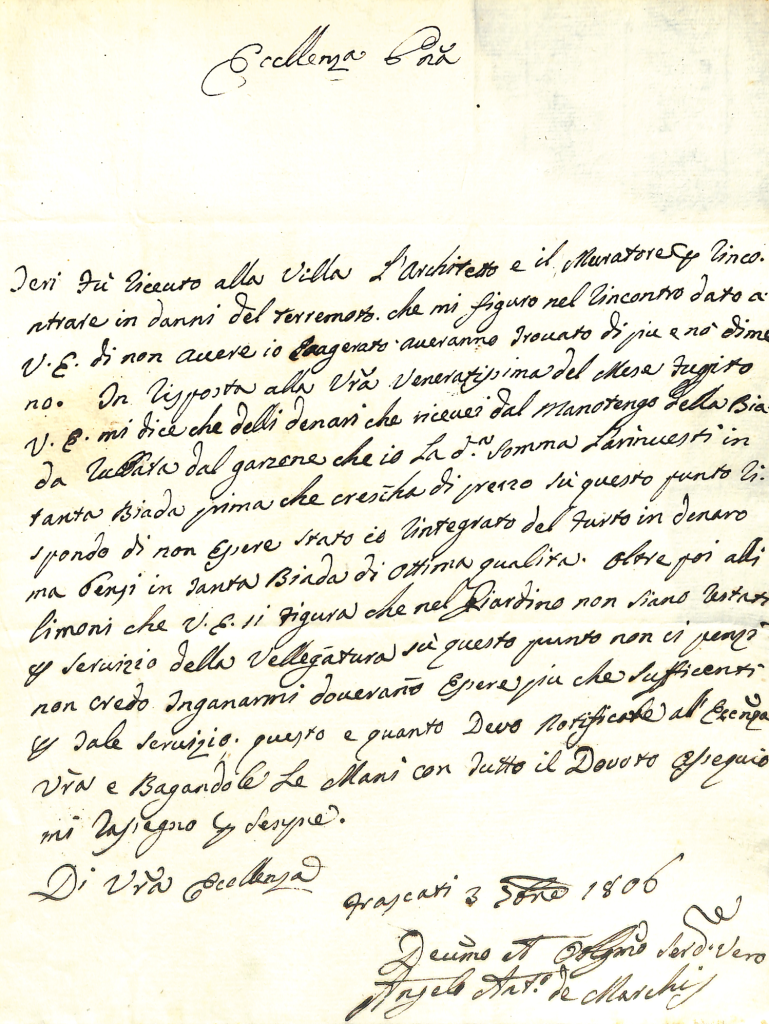

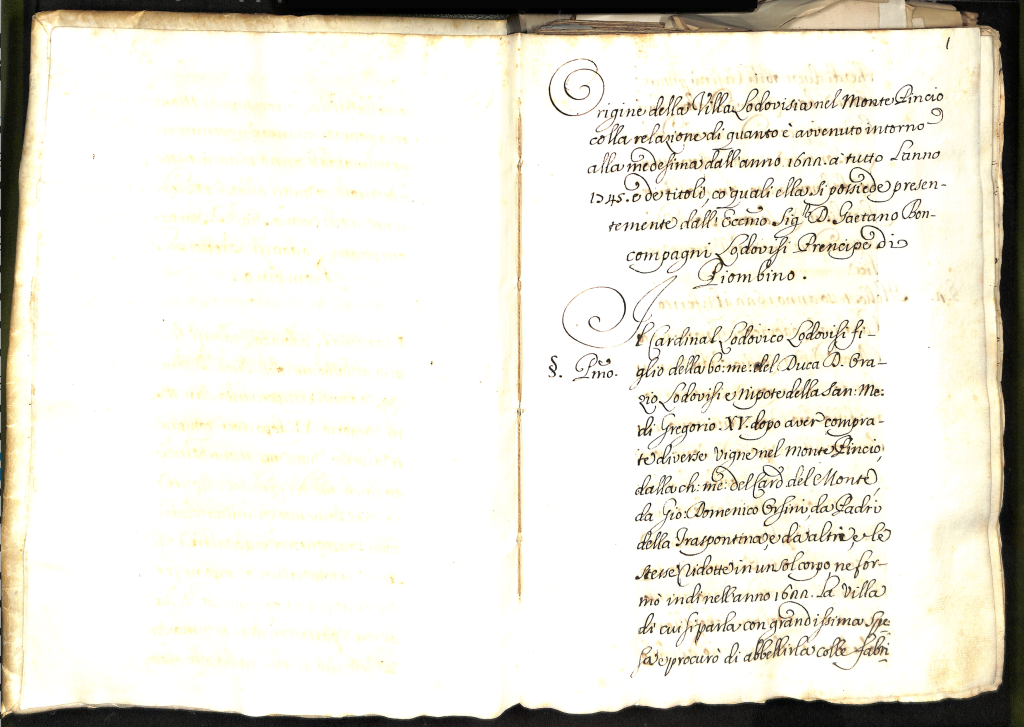

Indeed, it is documented that Ludovico Ludovisi had to do a bit of digging to form a coherent garden retreat from his patchwork of Pincio properties. In the Cardinal’s Master Books for late 1622 and early 1623, one finds expenses paid to the famed architect Carlo Maderno for excavating and leveling portions of the property.

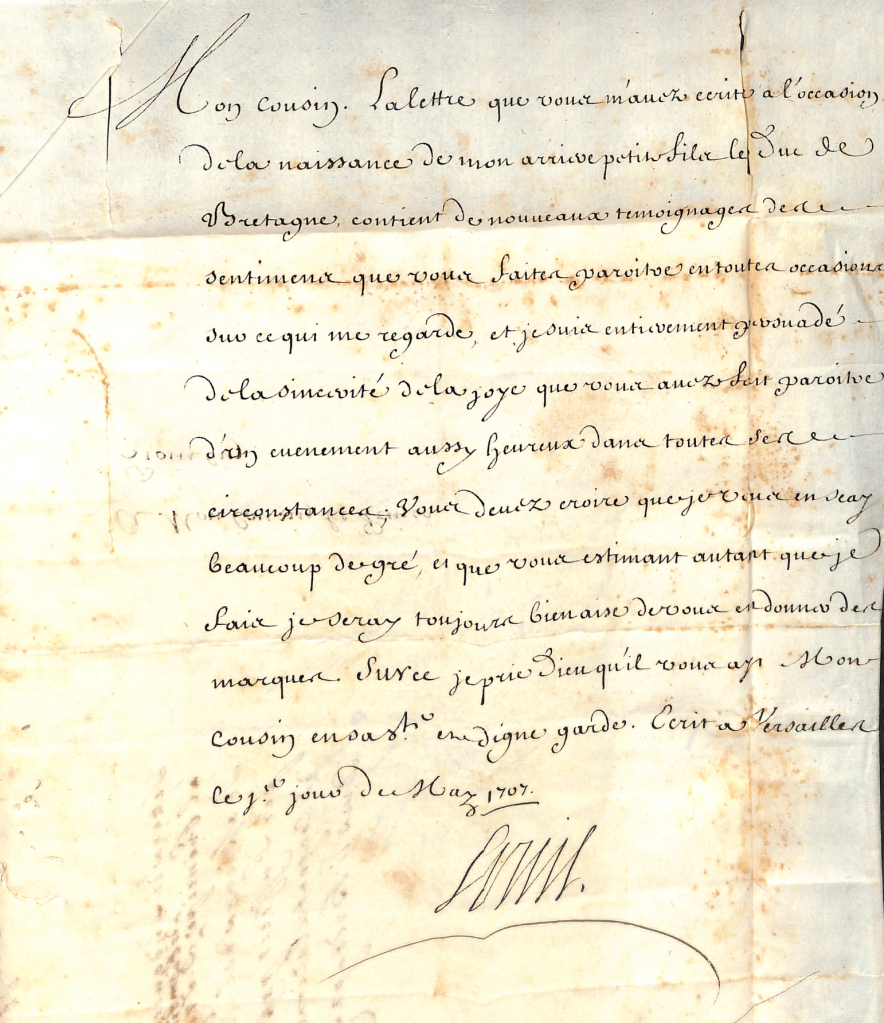

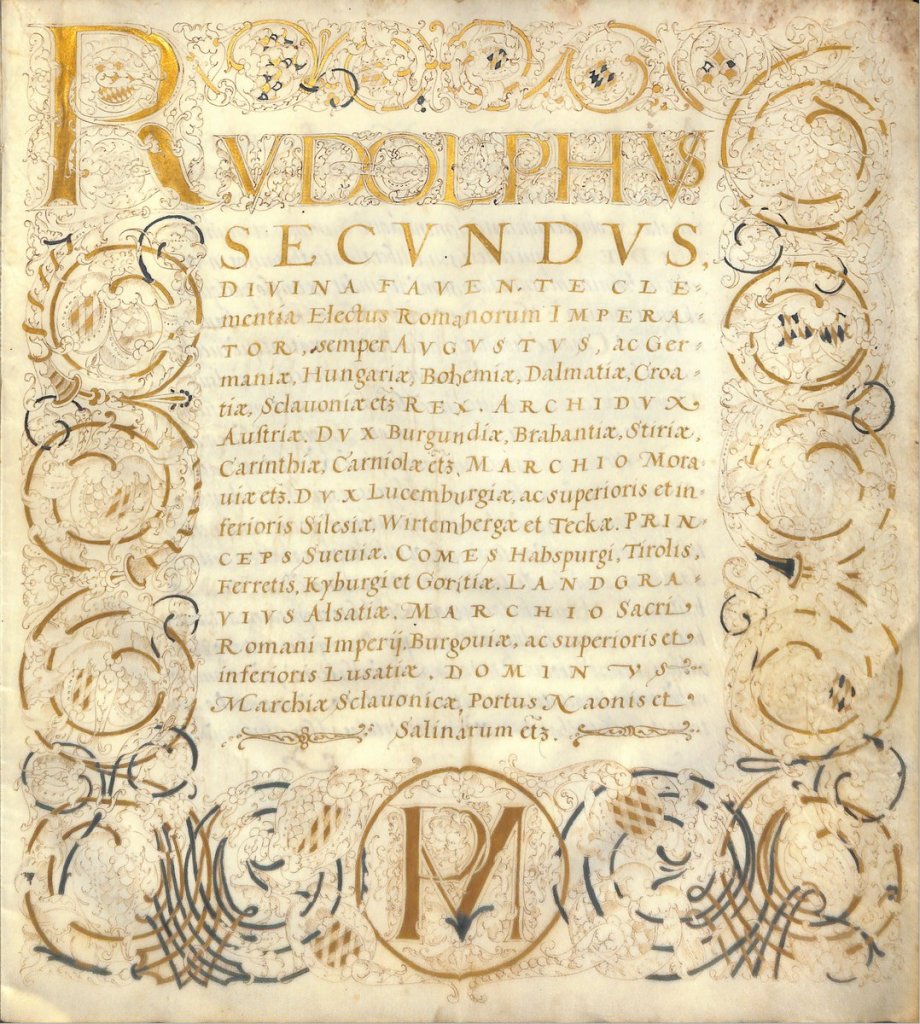

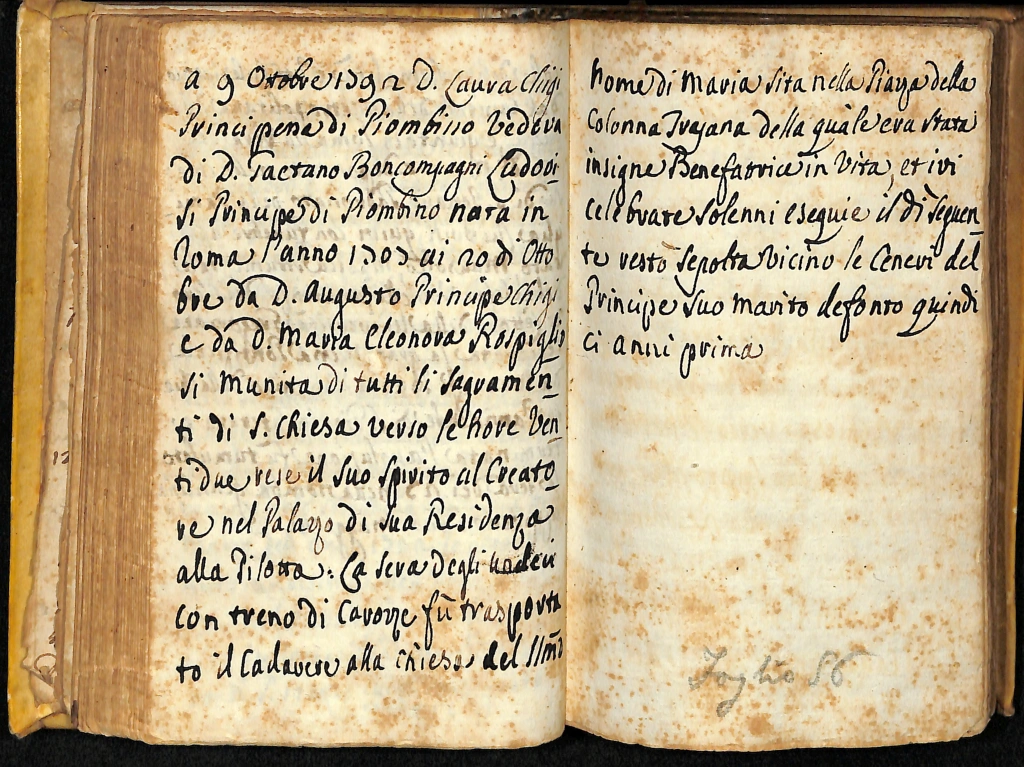

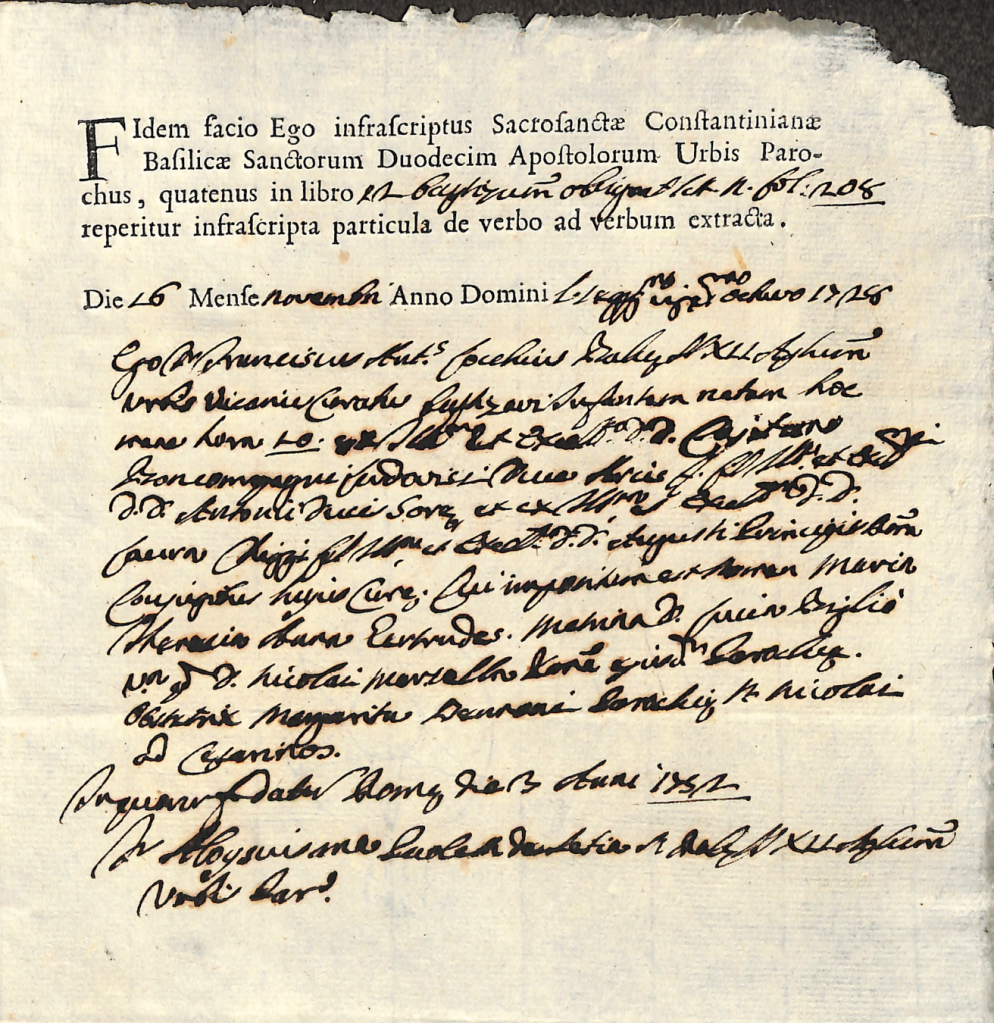

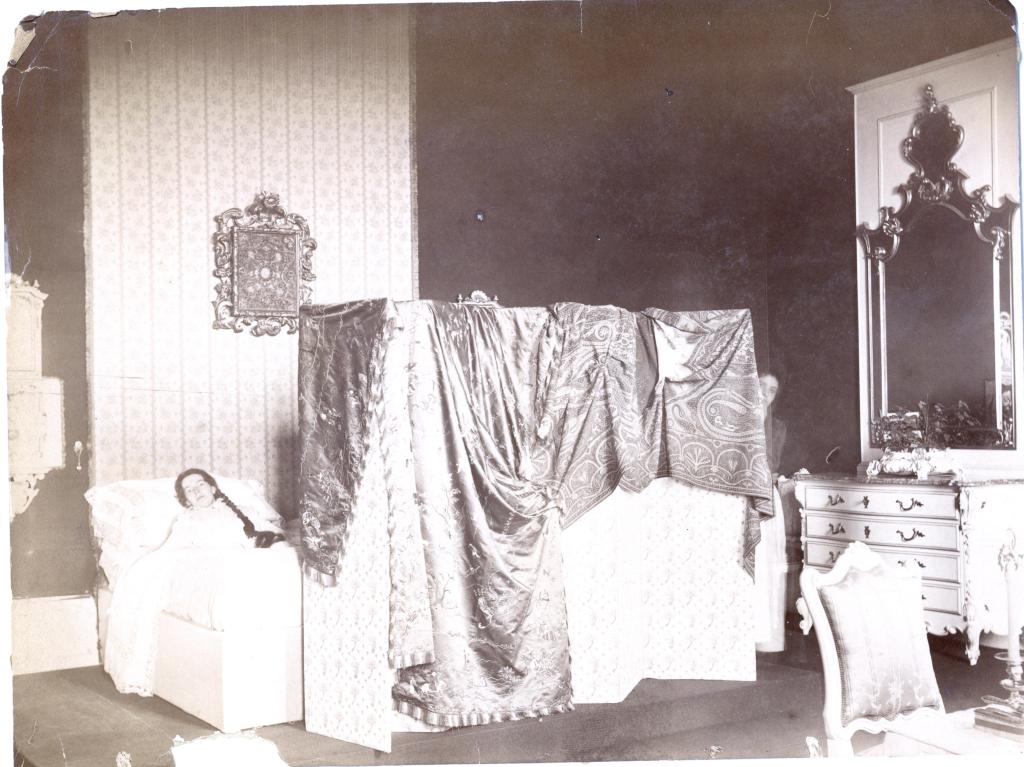

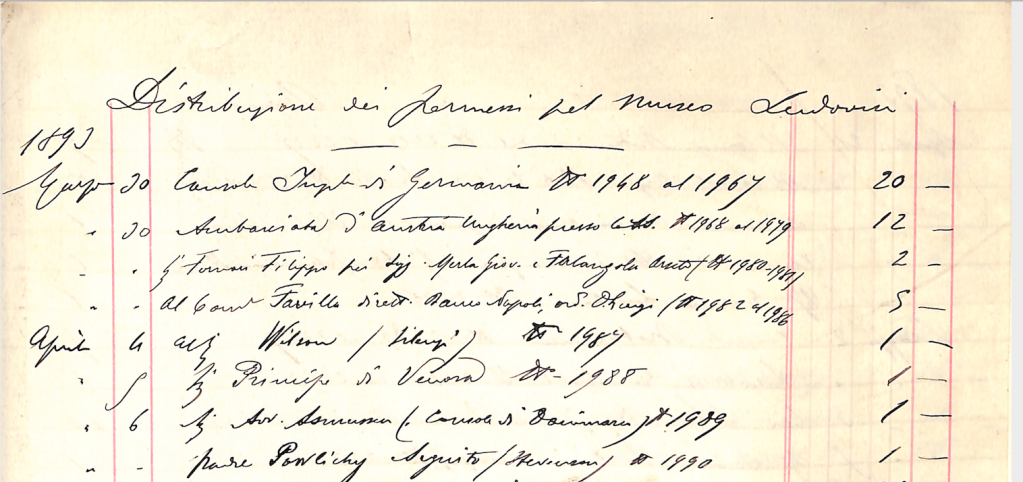

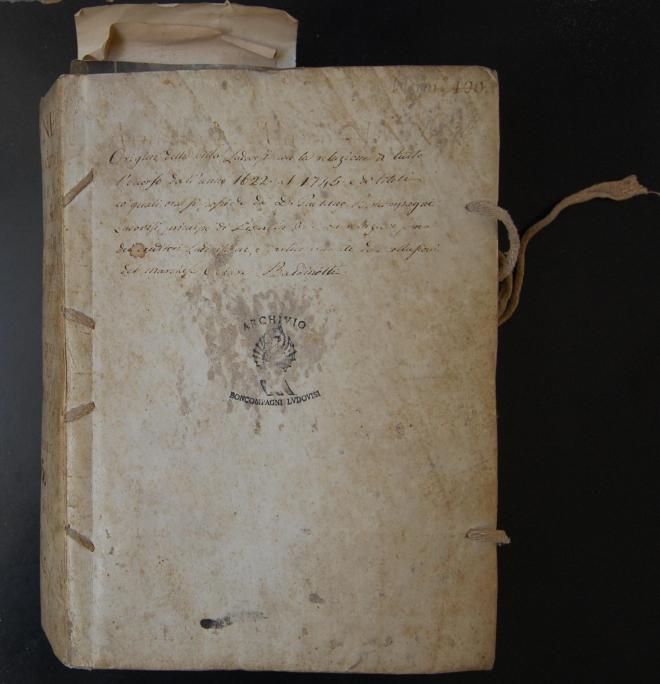

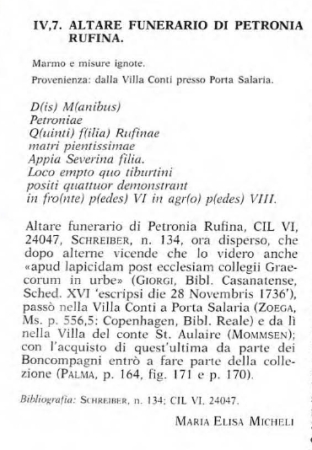

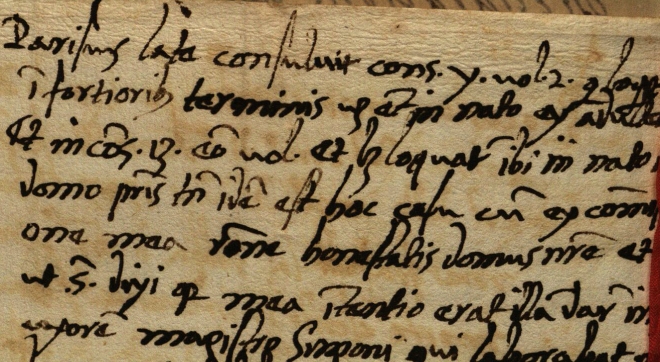

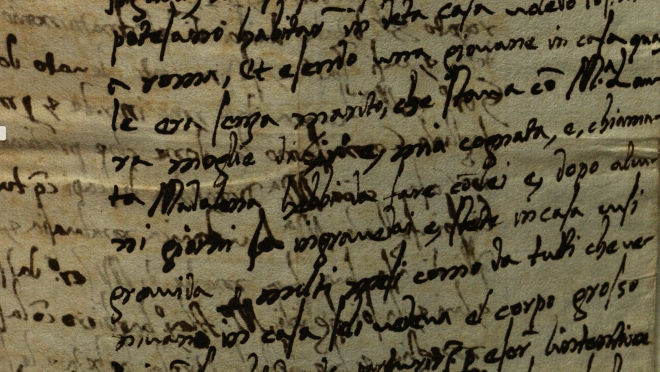

Detail from first page (1R) of a Villa Ludovisi account book (Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 365). Collection of HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome.

Though contemporary records are silent on the matter, it does seem wholly possible that Maderno’s work uncovered a certain number of antiquities.

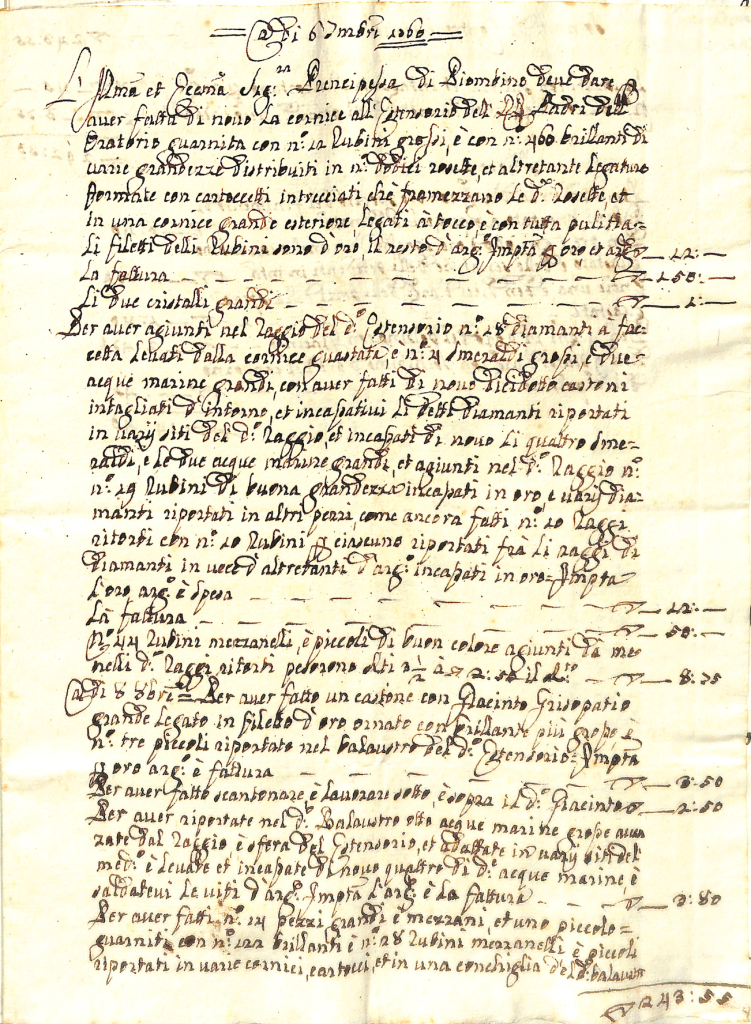

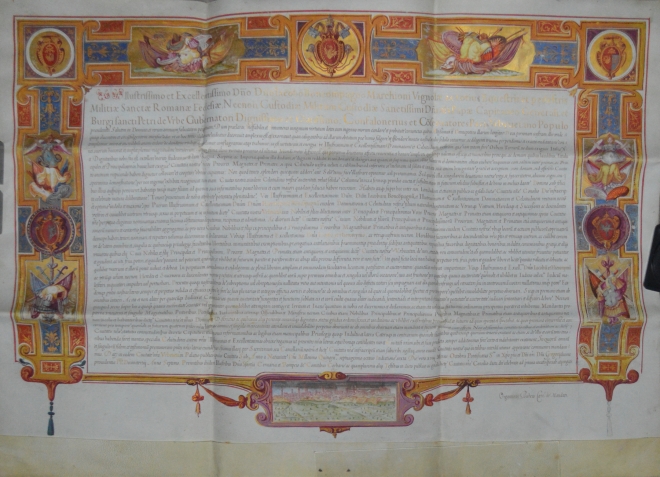

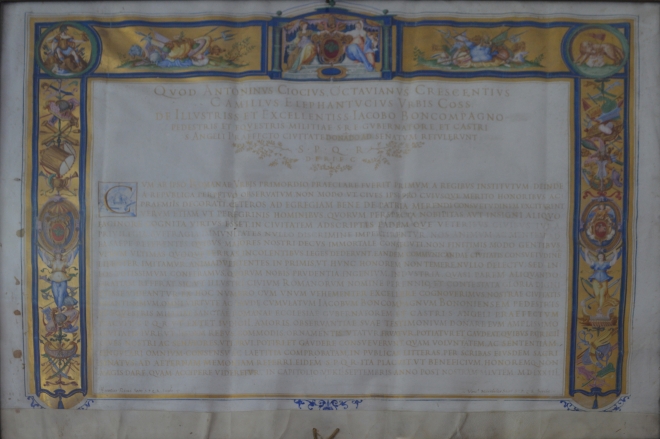

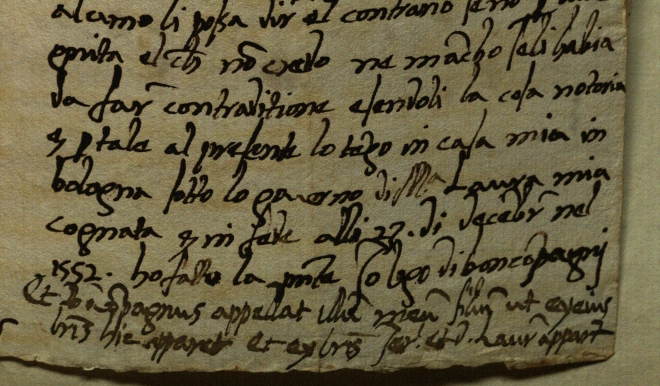

To adduce just one corroborating piece of evidence: a full 120 years later, a lease contract for a portion of Villa Ludovisi land (dated 14 March 1744) stipulates that the male head of family had the right to “hard and soft marbles of any size, statues and spires, bas-reliefs, metals, carvings, columns, inscriptions, heads, busts, and other sculptures or similar objects” found during agricultural work (Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 612, no. 101). The formulation of the contract suggests that such chance discoveries were common on Ludovisi land.

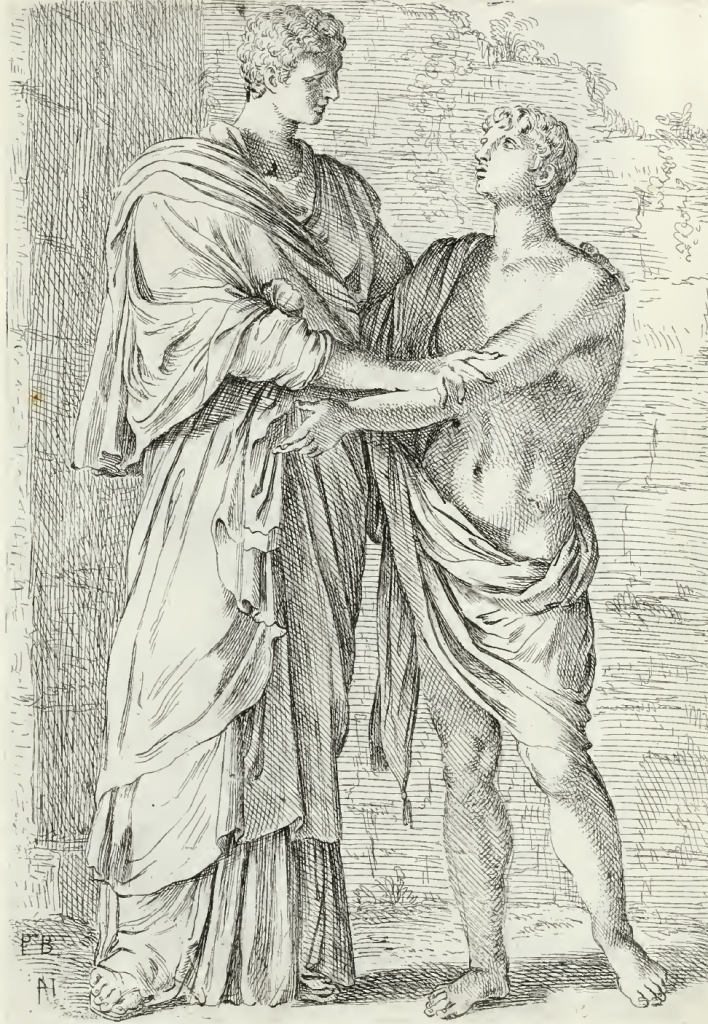

Indeed, by the mid-18th century, we find outsiders stating flatly that some of the principal highlights of the ancient portions of the Ludovisi collection were found on the premises, a notion which demonstrably boosted the Villa’s fame. Cited in this connection are the “Dying Gaul” (since 1734 in the Capitoline Museums), plus the “Electra and Orestes” group and the colossal “Juno Ludovisi” head (now in the Museo Nazionale Romano Palazzo Altemps).

The staff of the Villa did their part to reinforce this evocative idea. “As soon as the stranger sees these treasures”, wrote Emil Braun in 1854 of the Ludovisi sculptures, “he is wont to inquire as to their provenance, and to be answered that they were most probably in the area of this magnificent villa, which spreads out on the grounds of the Gardens of Sallust, to have been excavated. No one will wish to doubt the possibility of such an assumption, though we must not conceal from ourselves the utter lack of any information to suggest it.”

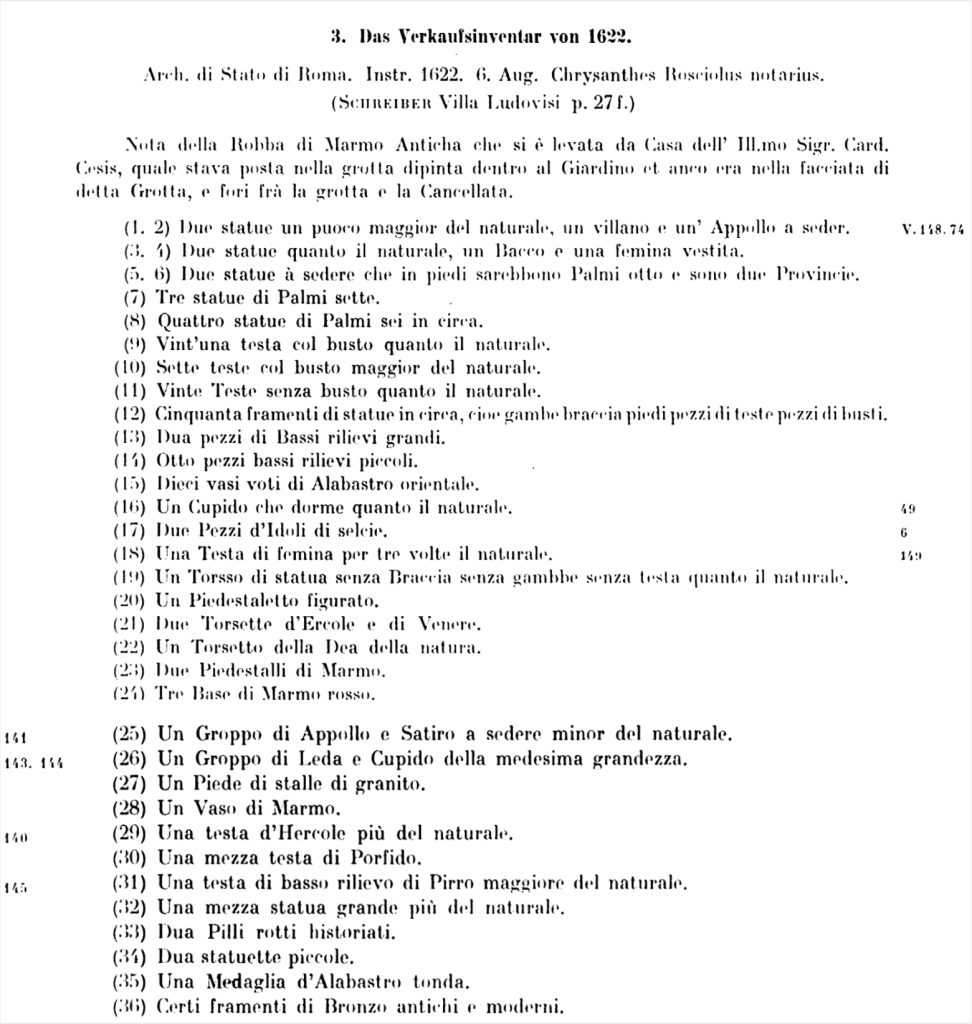

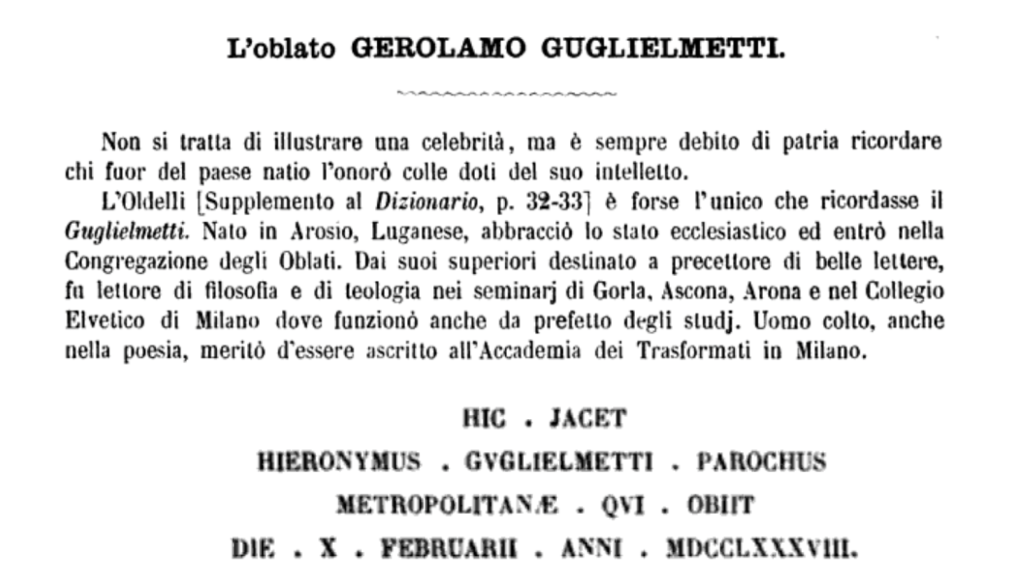

In 1880 Theodor Schreiber, on the basis of family archival records which he was the first scholar to consult thoroughly, set out a more nuanced explanation: some sculptures the Cardinal received by gift, others he bought, including the wholesale purchase of some great 16th century collections such as those of the Cesi and Cesarini. Others he may have found. But he emphasized that the provenance of some of the most famous Ludovisi pieces remains a mystery.

Drawing of the “Electra and Orestes” group in the Villa Ludovisi, from F. Perrier, Segmenta Nobilium Signorum et Statuarum (1638).

Here’s what we think is a new suggestion. Perhaps Ludovico Ludovisi in developing his urban retreat did not make a series of wholly new and spectacular archaeological finds. Rather he found some of his sculptures by digging up part of an extensive 16th century collection, that had been buried on the ex-Orsini part of his property at some point before the year 1564.

As it happens, it is securely attested that Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi (1505-1564), the bishop of Pavia who owned the Rome vigna that passed directly to the Orsini and then (in 1622) Ludovico Ludovisi, hid a significant number of sculptures on that property in this way, and died before he recovered them. And five years after his death, the sons of his great Florentine patron Cosimo (I) de’ Medici, Cardinal Francesco and Ferdinando, went looking for those pieces on Orsini land, with mixed success.

So why did Bishop de’ Rossi bury a large number of statues? To us, even a cursory glance at his biographical details reveals that he had very good reason to do so.

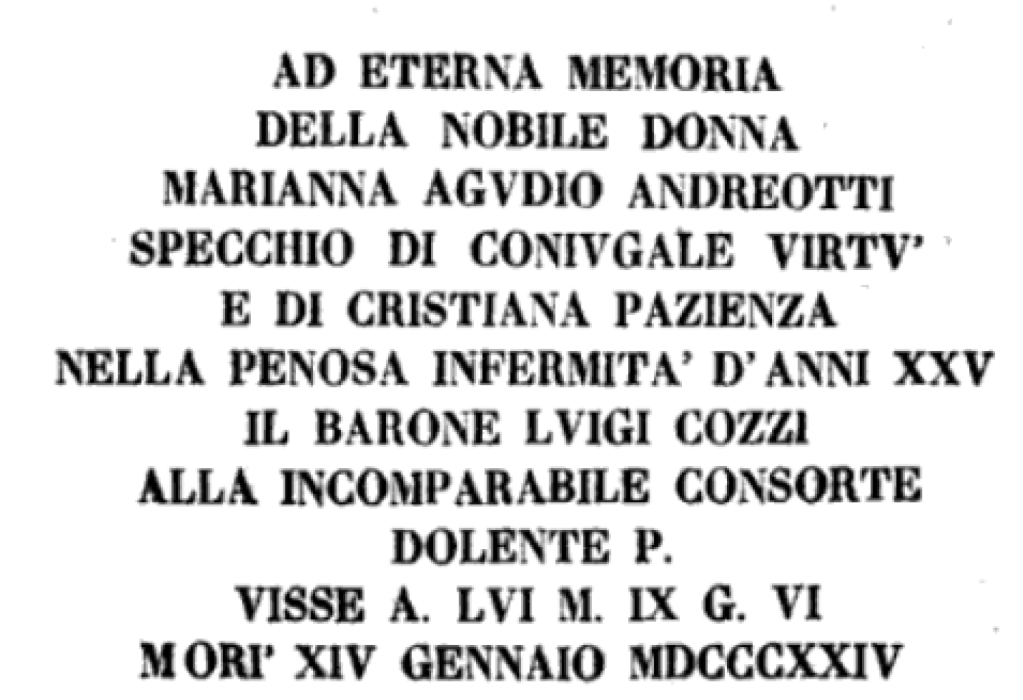

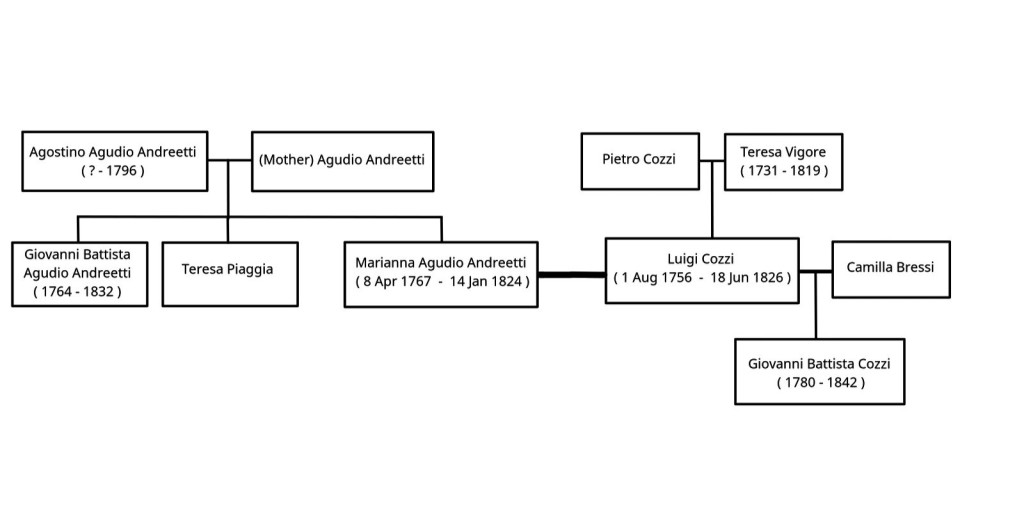

Giovangirolamo’s parents, wed in 1503, were the condottiere Troilo (I) de’ Rossi (ca. 1462-ca. 1521, I Marquis and VI Count of San Secondo) and Bianca Riario (1478-1522). Giovangirolamo was born to them in San Secondo, 15 km northeast of Parma, on 19 June 1505.

Medal ca. 1488-1490 with obverse portrait of Caterina Sforza Riario (1463-1509), by Niccolò Spinelli (aka ‘Fiorentino’). Credit: Jean Elsen & ses Fils

Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi’s family was pugnacious on both sides. To note just Giovangirolamo’s maternal line: his mother Bianca was daughter of Girolamo Riario, Lord of Forlì and Imola, one of the organizers of the Pazzi Conspiracy of 1488 to kill Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici, and himself assassinated at Forlì in 1488, and Caterina Sforza, daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, descended from a long line of condottieri.

There is more. Thanks to her mother’s remarriage to Giovanni de’ Medici, Bianca Riario became also the stepsister of Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, one of the greatest men-at-arms of the Italian Renaissance. Furthermore she was great-niece of Pope Sixtus IV della Rovere (reigned 1471-1484), and cousin of Pope Julius II della Rovere (1503-1513). It is not so surprising to find a young Bianca Riario as a character in the violent video game Assassin’s Creed II (2009).

Medal (obverse) in style of Niccolò Spinelli (aka ‘Fiorentino’) with portrait of Bianca Riario (1478-1522). Credit: National Gallery of Art

In the event, Bianca’s son Giovangirolamo gained a crucial connection from the fact that she was first cousin of Cardinal Raffaele Sansoni Riario (1461-1477-1521), best known as the first important patron of Michelangelo in Rome. (The Cardinal was son of Antonio Sansoni and Violante Riario, the latter the sister of Bianca’s father Girolamo.) Though the relationship may seem a bit distant, Cardinal Riario took a direct interest in the young Giovangirolamo. When the youth was just 12 years old, Riario directed to him the benefits of the rich Cistercian abbey of Chiaravalle della Colomba, in the area of Piacenza. About the same time Pope Leo X de’ Medici appointed Giovangirolamo as apostolic protonotary.

Simplified family tree of the de’ Rossi of Parma family, late 15th / earlier 16th centuries. Credit: Hatice Köroglu Çam

The great 19th century genealogical historian Pompeo Litta has a lot to say about Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi in his Famiglie celebri italiane: Rossi di Parma (1835), including three credible accusations of murder. The first came at age 16: “in 1521, given the upheavals in the Parmesan states…he was sent to Venice, and it was good to keep him away, because he was naturally rebellious and overbearing. But what he couldn’t do in Parma he did in Venice, and on Good Friday followed by a crowd of servants dressed in the Guelf manner, accompanying the French ambassador to the church of St. Mark, insulted by Fantino Rampini of Piacenza, drawing his sword, he killed him in the church. To save him from justice, the solution was found for his brother Pier Maria to declare by act of a notary that he had ordered Rampini’s murder.”

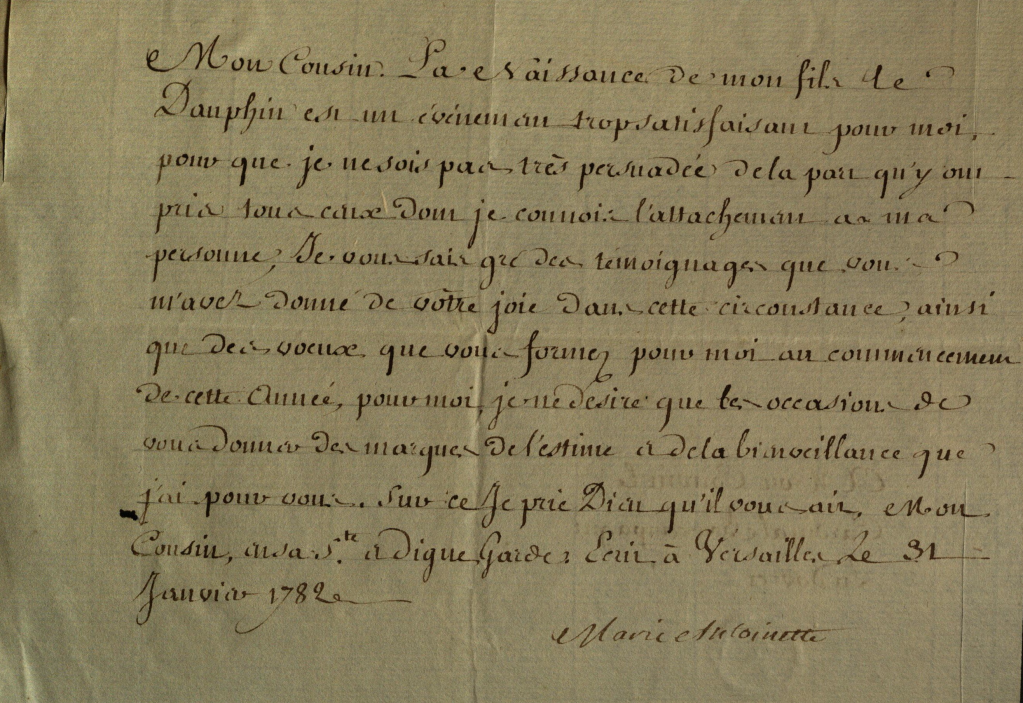

Litta then relates that Giovangirolamo “in 1527 after allegedly causing the death of his cousin Bernardo, he went to join Clement VII [de’ Medici] in Orvieto … and when the pope returned to his capital he followed him and in 1529 was elected chamber cleric. In 1530 he exchanged the clericate with Giammaria del Monte, who ceded to him the bishopric of Pavia, a church that was run by a vicar since Rossi had not yet been ordained to any sacred order.” From his positions in the Papal chamber and as bishop of Pavia, and as beneficiary of the Cistercian abbey near Piacenza, we know that his annual income now reached a whopping 25,000 scudi.

Four years later, in 1534, Giovangirolamo tried to press the jurisdictional rights of the diocese of Pavia over the feud of Rosasco, 45 km to its west. During this dispute, its Count Alessandro Langosco was killed. “No one knew where the shot came from”, says Litta, “and Rossi, on the occasion of the election of Pope Paul III [Farnese, on 13 October 1534], went to Rome.”

Far from feeling contrite over the Langosco affair, or his two previous accusations of murder, in Rome Giovangirolamo turned his energies to securing from the new Farnese pope an appointment as cardinal—an ambition never realized, but that would consume de’ Rossi for the rest of his life. His desire for promotion was so strong that in 1537 he even engaged in a ploy to bring Florence—then ruled by his Medici relatives—under papal control. His presence with Paul III in Parma and Piacenza in 1538 sparked not a homecoming celebration, but rather riots.

Yet soon Paul III turned against the whole de’ Rossi family. The tipping point seems to have been the misadventures of Giovangirolamo’s younger brother Giulio Cesare (1519-1554), who abducted the young countess Maddalena Sanseverino, and occupied her town of Colorno (15 km north of Parma). Giovangirolamo was suspected of complicity in these acts.

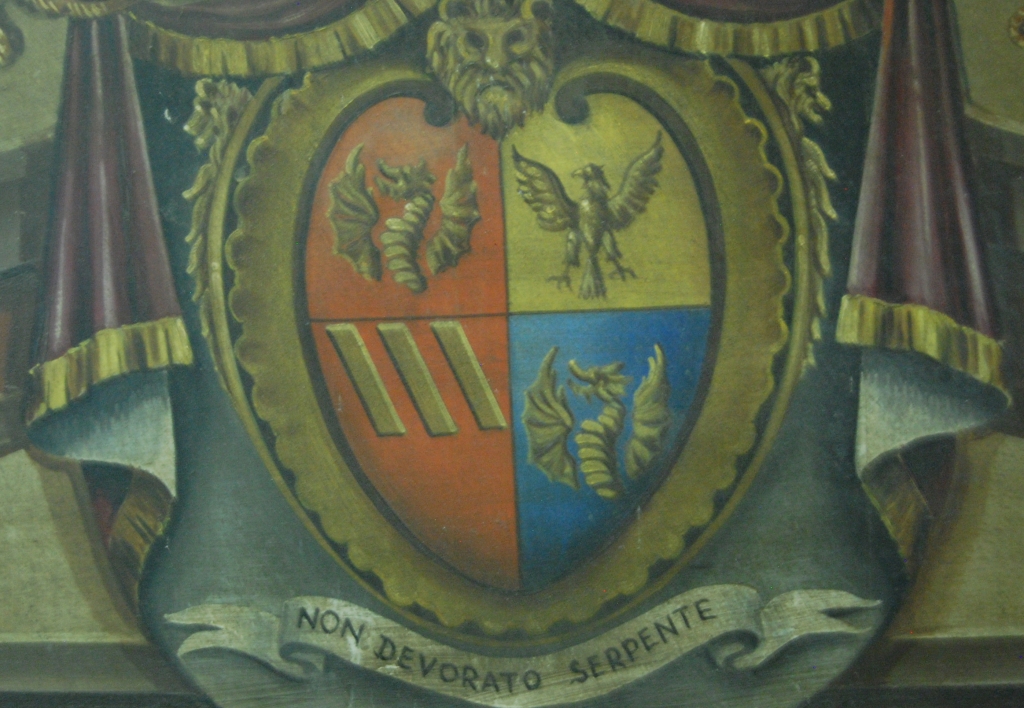

Arms of the de’ Rossi family of Parma, from P. Litta, Famiglie celebri di Italia. Rossi di Parma (1838)

Pompeo Litta details what happened next. “Called under pretext to Parma, the papal legate in 1539 sent him to Rome, where he was imprisoned in Castel S. Angelo …” There he formed a bond with the goldsmith, sculptor and diarist Benvenuto Cellini, who attests to the harsh conditions they shared.

“Among [de’ Rossi’s] charges was the death of Count Langosco [in 1534], but the truth was never reached …”, continues Litta. Indeed, we have the transcripts of the trial, which stretched from 4 November 1539 to 4 July 1541, and resulted in a guilty verdict. Despite the testimony of eminent character witnesses, including the great humanist Pietro Bembo, “after two years of imprisonment he was exiled to Città di Castello [near Perugia] in 1541. However, he lost the abbey and the bishopric, which returned to his predecessor [Giammaria] Del Monte.”

Until the death of Paul III Farnese in November 1549, Rossi was barred from Rome and the Papal States, though he had freedom of movement elsewhere. He resided first in Florence, then Paris, then (in 1545) Ferrara, and (in 1546) Florence again.

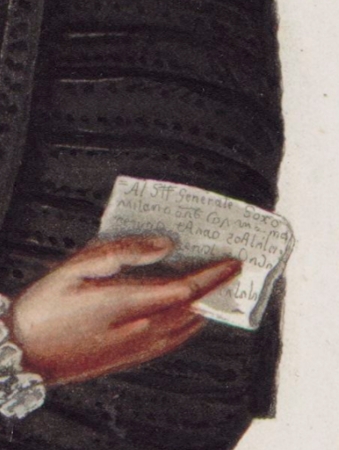

In 1547, de’ Rossi is found in Pisa, composing sonnets for the deaths of Pietro Bembo and Michelangelo’s “muse”, the poet Vittoria Colonna. (He had been writing poetry since at least the mid-1520s.) That same year, he is found back in Florence, commissioning two paintings from Giorgio Vasari. In January 1548, Giovangirolamo joined his relative Ferrante Gonzaga, governor of the state of Milan, accompanying him also to Piacenza. It was through Gonzaga that de’ Rossi once again got his hands on the lucrative abbey of Chiaravalle, originally gifted to him in 1517 by his maternal cousin Cardinal Raffaele Riario.

What followed was a significant reversal in Giovangirolamo’s ill-starred fortunes of the past dozen years. The new pope, Julius III del Monte (reigned 1550-1555) “restored the bishopric to Rossi”, as Litta tells us, “and called him to Rome in 1551 as governor, and would have conferred the purple [i.e., of the cardinalate] on him if the Farnese family had not vehemently opposed his elevation…in 1555 he left the Roman court and returned to Tuscany …”

And it was in Tuscany where Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi spent his final years, under the protection of his cousin, the second Duke of Florence, Cosimo (I) de’ Medici. Giovangirolamo retired to the Villa del Barone, near Montemurlo, set between Prato and Pistoia. Though ostensibly devoting himself to literary pursuits (poetry and history), and seriously challenged by gout, he still was on the look-out for potential assassins.

Gilded bronze medal (ca. 1567) by Pietro Paolo Galeotti with obverse portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici, second Duke of Florence (1519-1574). Credit: Baldwin’s Auctions.

On this score, a letter from 8 January 1561 that de’ Rossi wrote to Cosimo de’ Medici is instructive. Here Giovangirolamo points out that he is allowed “…due to the enmities I have, to keep with me for my safety some wheel-lock guns, large and small; you replied to me in formal words, that I should not only keep these, but also some artillery… And certainly for several months now, I had almost stopped using them, but seeing before my eyes that Alessandro Conversini [of Pistoia], who killed my brother [i.e., Giulio Cesare †1554], who used to come often half a mile to the [Villa del] Barone, and fearing for my life, has made me decide… to put them into use…” [CC, 487, 609r]. One imagines that for the artillery the bishop had at least a small company of men-at-arms at his disposal.

In the event, Bishop Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi was to meet a natural death, at his villa of Il Barone on 5 April 1564. Two nephews, both career military men, saw to Giovangirolamo’s burial arrangements in the old Prato church of Santa Trinità: Sigismondo and Ferrante de’ Rossi, sons respectively of the deceased’s elder brother Pier Maria (†1547) and younger brother Giulio Cesare (†1554).

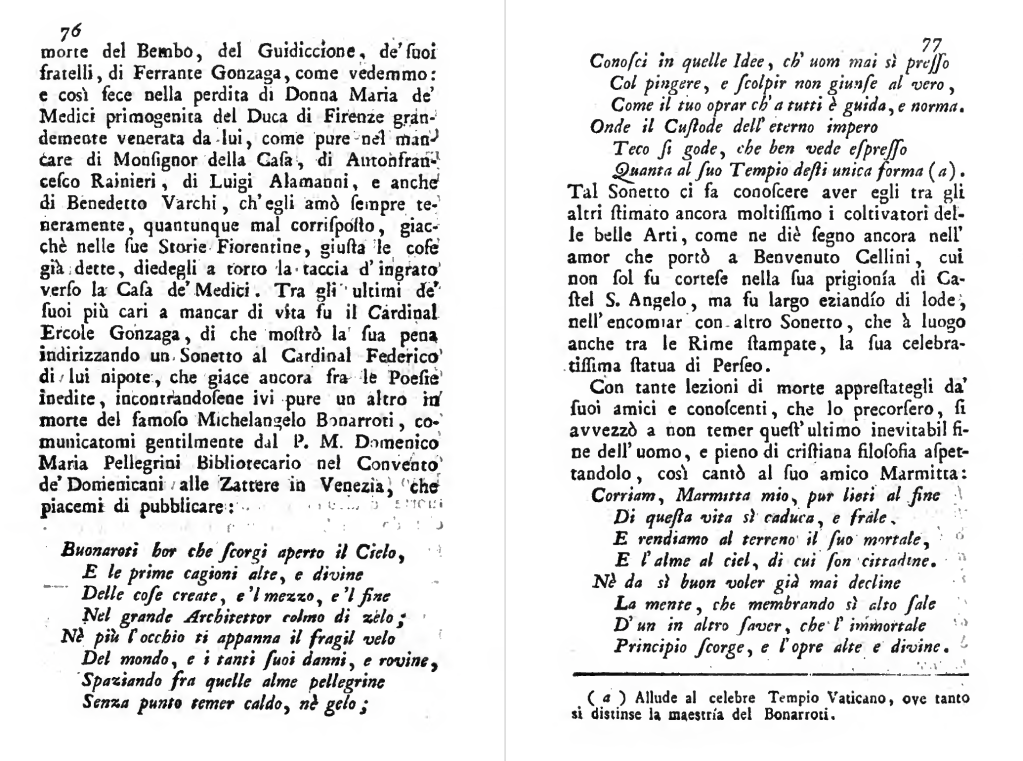

Excerpt from P. Ireneo Alfà, Vita di Monsignore Giangirolamo Rossi de’ Marchesi di San Secondo Vescovo di Pavia (1785).

Even through his last days, Giovangirolamo managed to sustain his literary efforts. Upon learning of Michelangelo’s passing (18 February 1564), he penned a sonnet that pictures the great artist being received into heaven by the supreme Creator. It includes these lines:

“As you wander among those blessed souls without fear of heat or cold. / You recognize in those Ideas, which no one ever approached so closely in painting and sculpture, / The truth of your work, which serves as a guide and a standard for all. / Therefore, the Custodian of the eternal realm rejoices with you, / For he sees clearly how you gave a unique form to his temple [i.e., S. Peter’s]”.

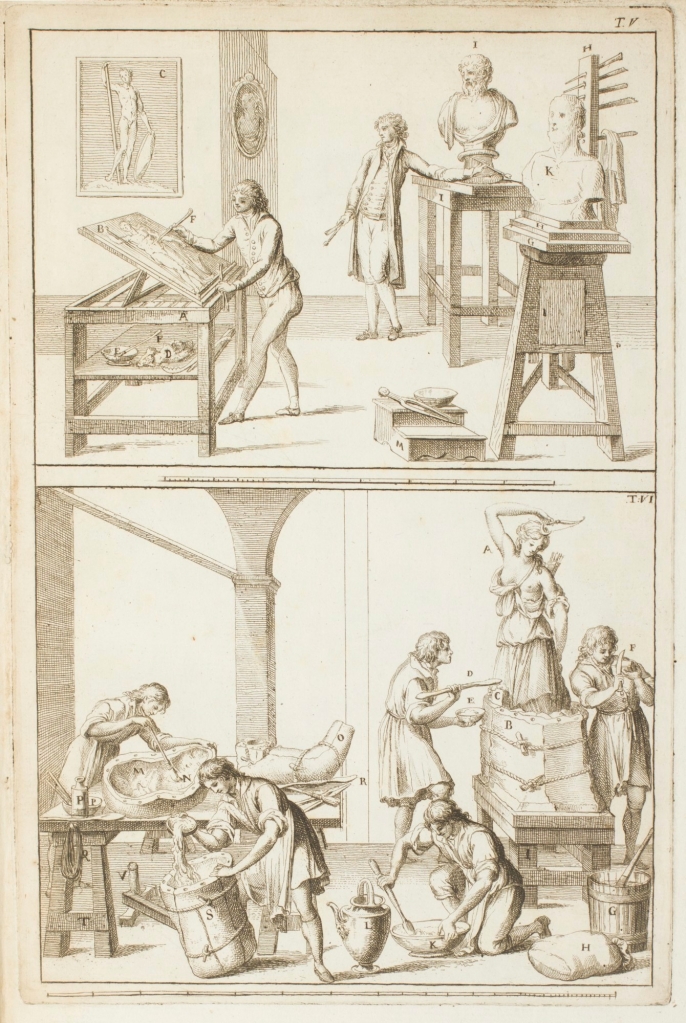

There is much one can detail about the cultural interests of Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi, but here we will focus just on his passion for collecting sculptures. “What can I say”, offers the bishop’s 18th century biographer M. I. Affò [p94], “about the ancient marbles, the work of Greek and Roman chisels, which he acquired with great industry and expense, aiming to enrich his aforementioned gallery? Certainly, he spared no effort in this regard, and I must also commend the goodwill of the antiquarians who diligently scoured for such items on his behalf, which he generously compensated.”

Yet it should be clear by now that Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi’s rich but quarrelsome family background and tumultuous career gave him sufficient grounds for fearing the confiscation, theft or loss of the sculptural treasures on his Pincio estate in Rome.

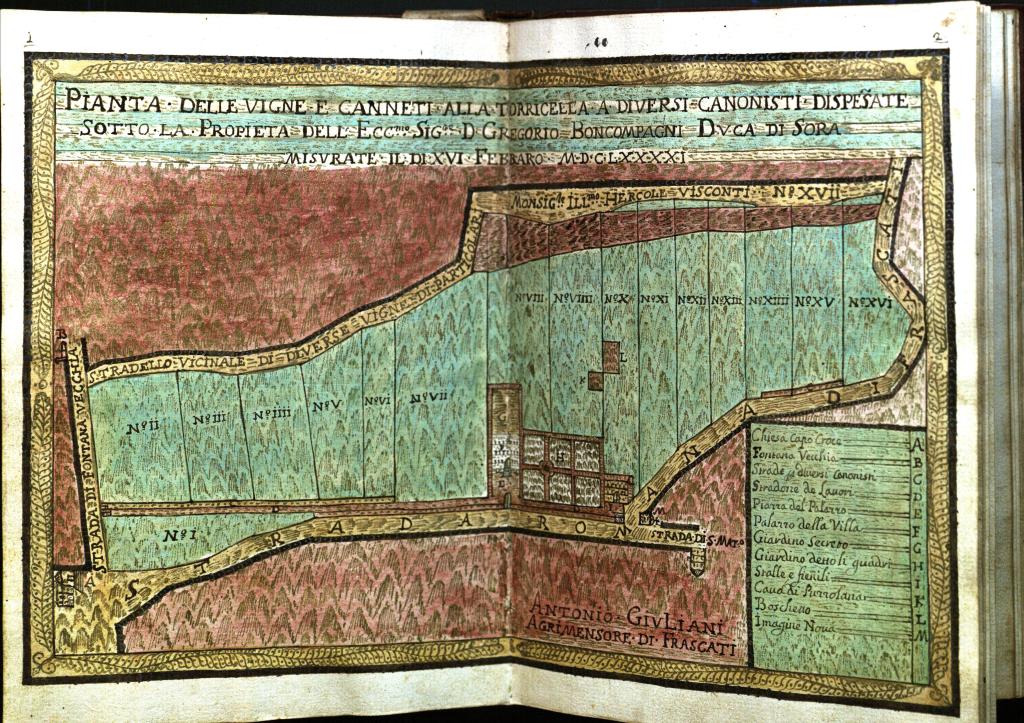

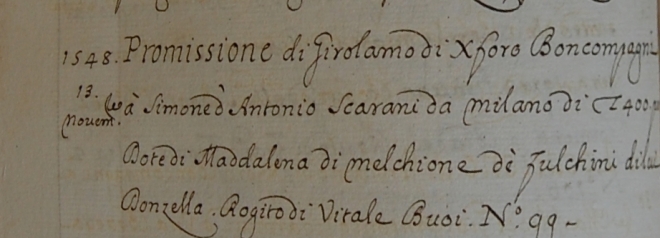

It would be good to know when Giovangirolamo bought that vigna. We know the name of a previous owner (Alessandro Morelli), but not the date when the bishop acquired it, or if it was from that man. On the face of things, the most likely dates for a purchase would be during one of de’ Rossi’s two extended sojourns in Rome, either in the span 1534-1539 (before his arrest and imprisonment in Castel S. Angelo), or 1551-1555 (his tenure as papal Governor of Rome).

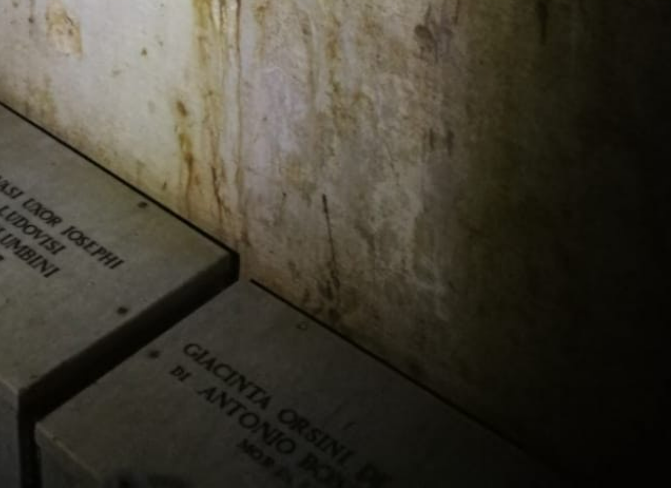

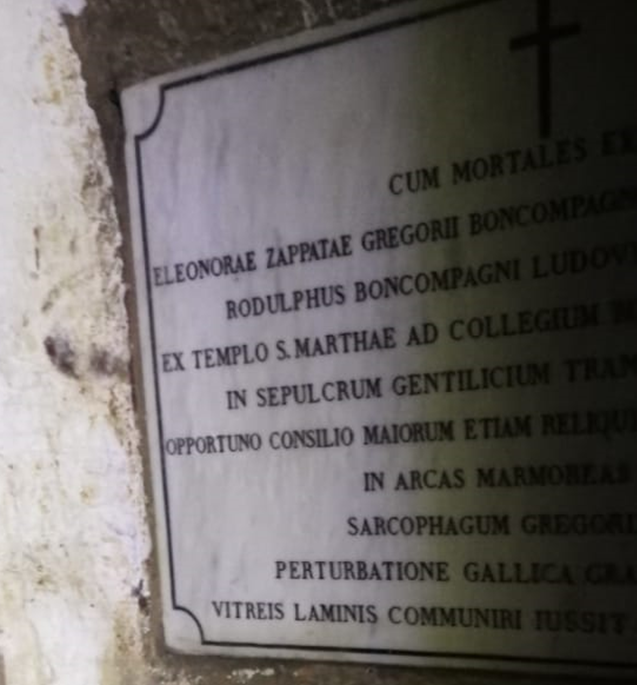

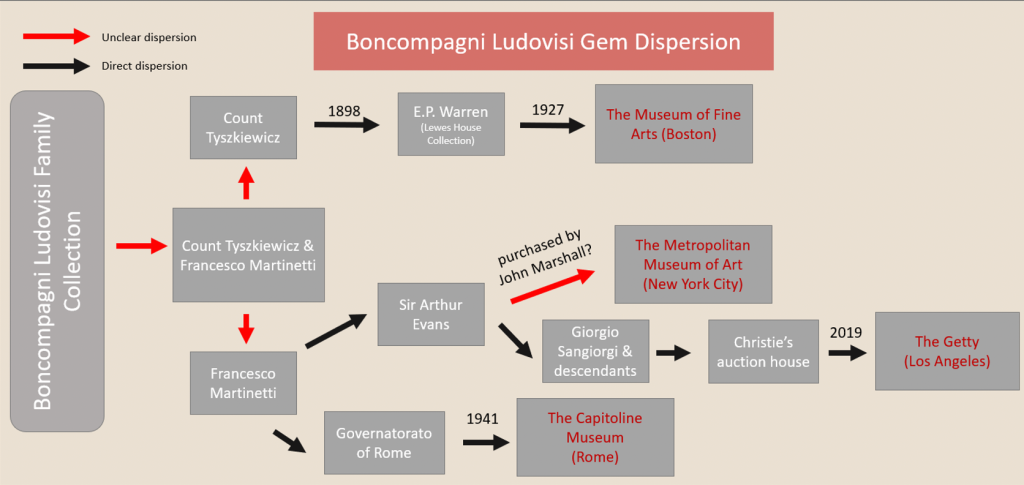

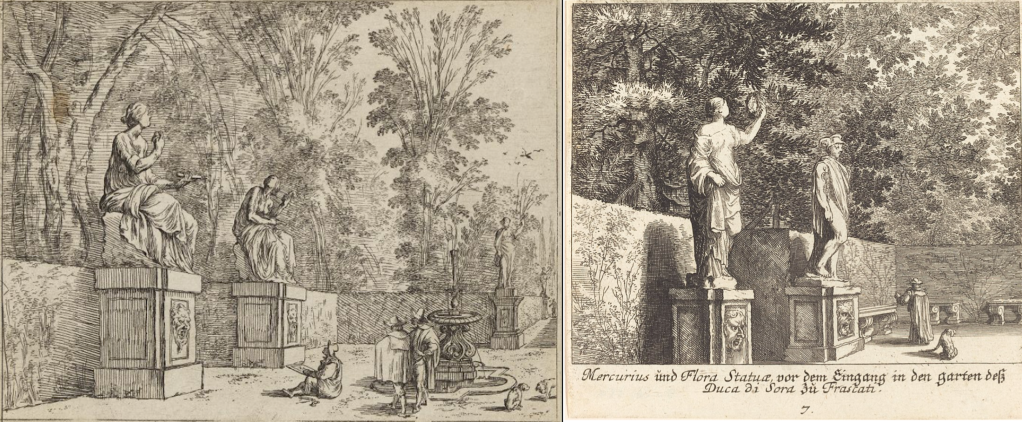

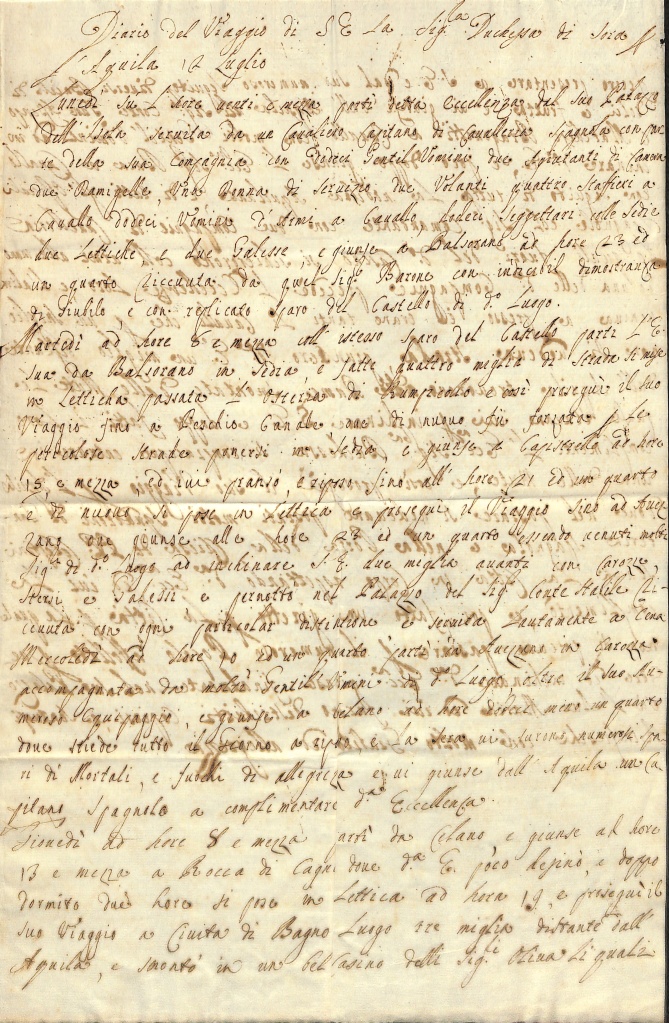

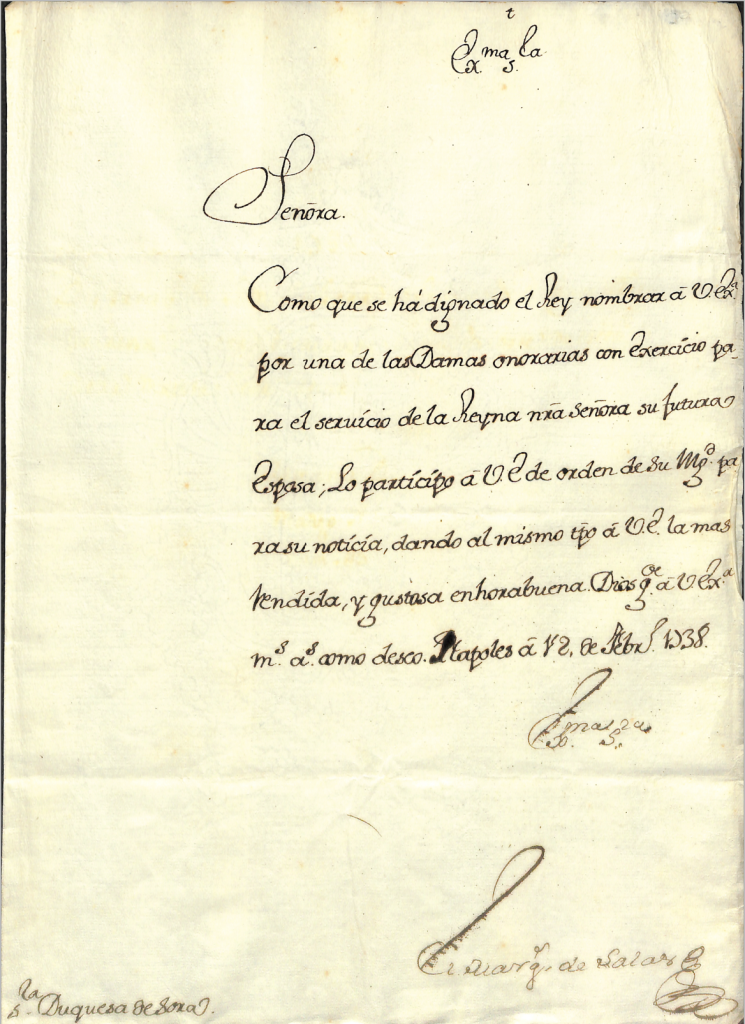

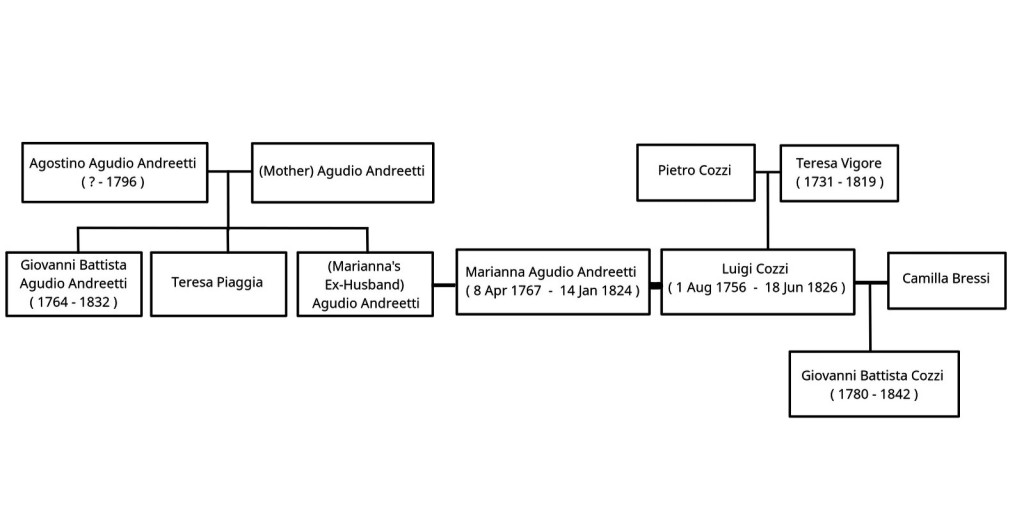

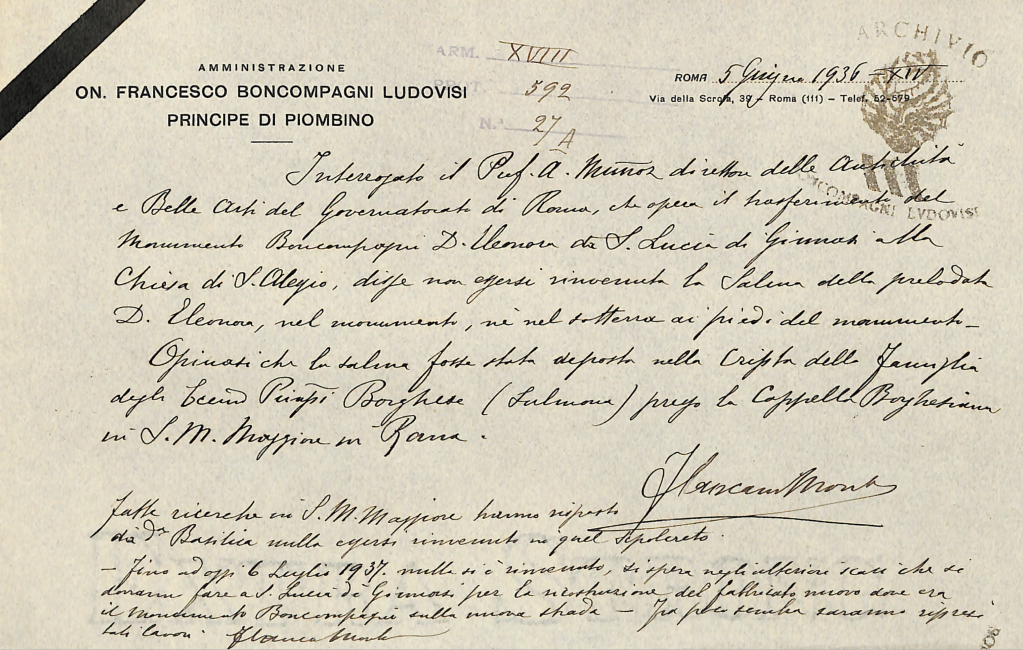

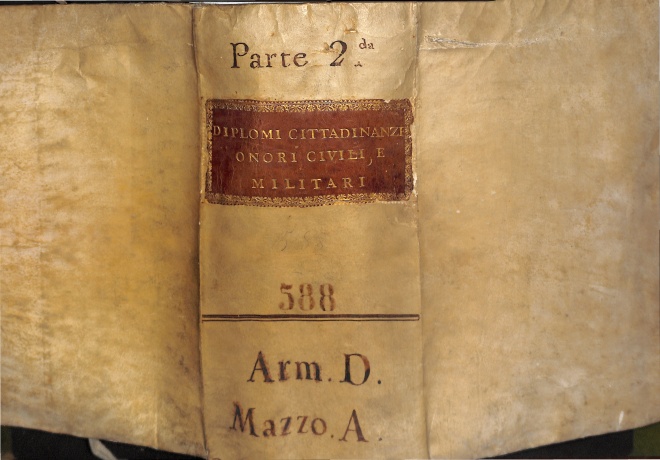

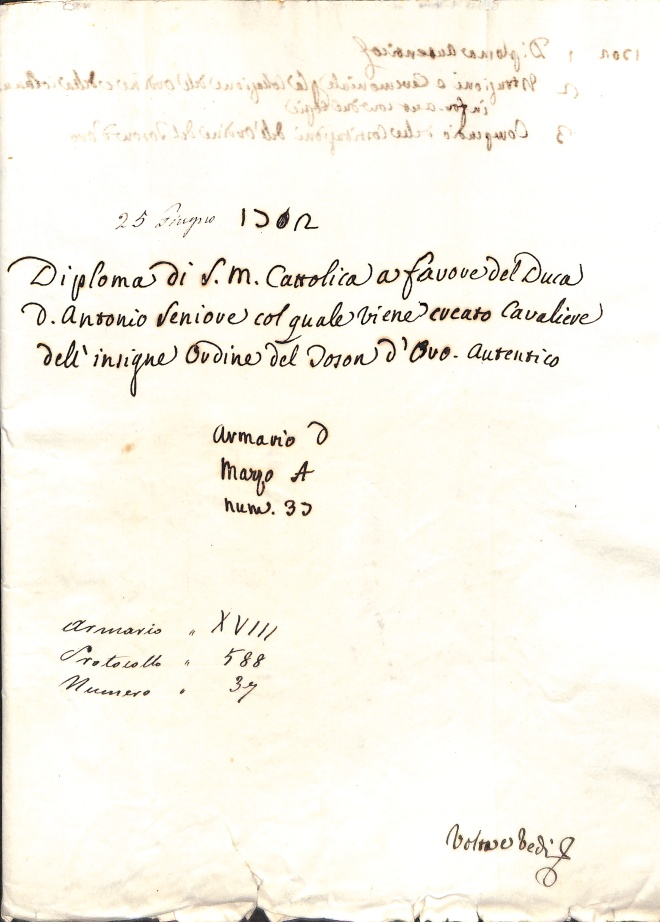

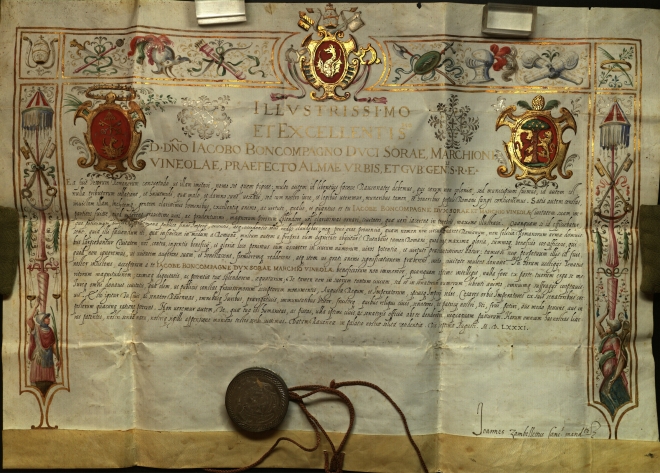

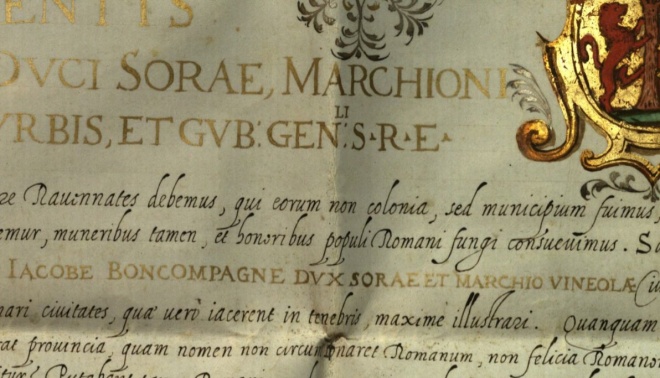

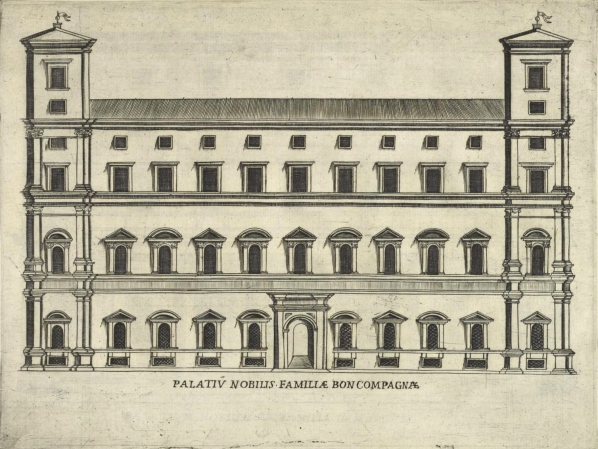

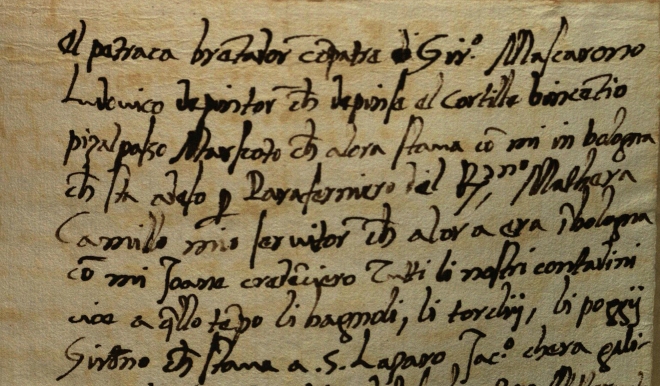

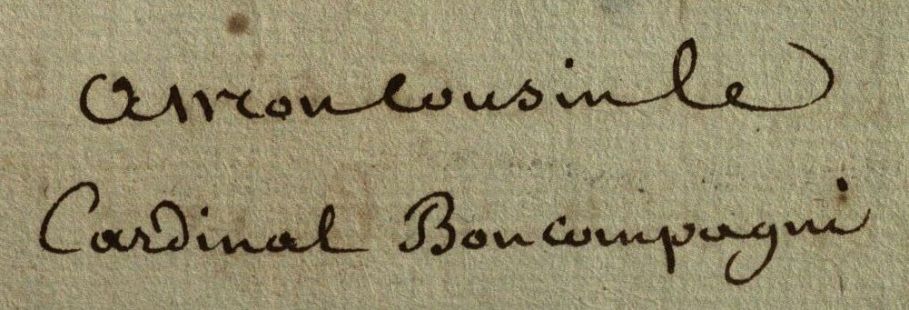

On Giovangirolamo’s death, his nephew, the condottiere Sigismondo de’ Rossi (1524-1580), inherited among much else the Pincio property, and promptly sold it to one Julia Petrucci. Then before 1569, Petrucci sold it to Cardinal Flavio Orsini (1532-1565-1580) [Archivio Boncompagni Ludovisi prot. 611 no. 31]. The estate later passed to the cardinal’s nephew, Giannantonio Orsini (born 1577), who in 1622 sold it—as a fully developed villa with a grand palace and formal gardens—to Ludovico Ludovisi.

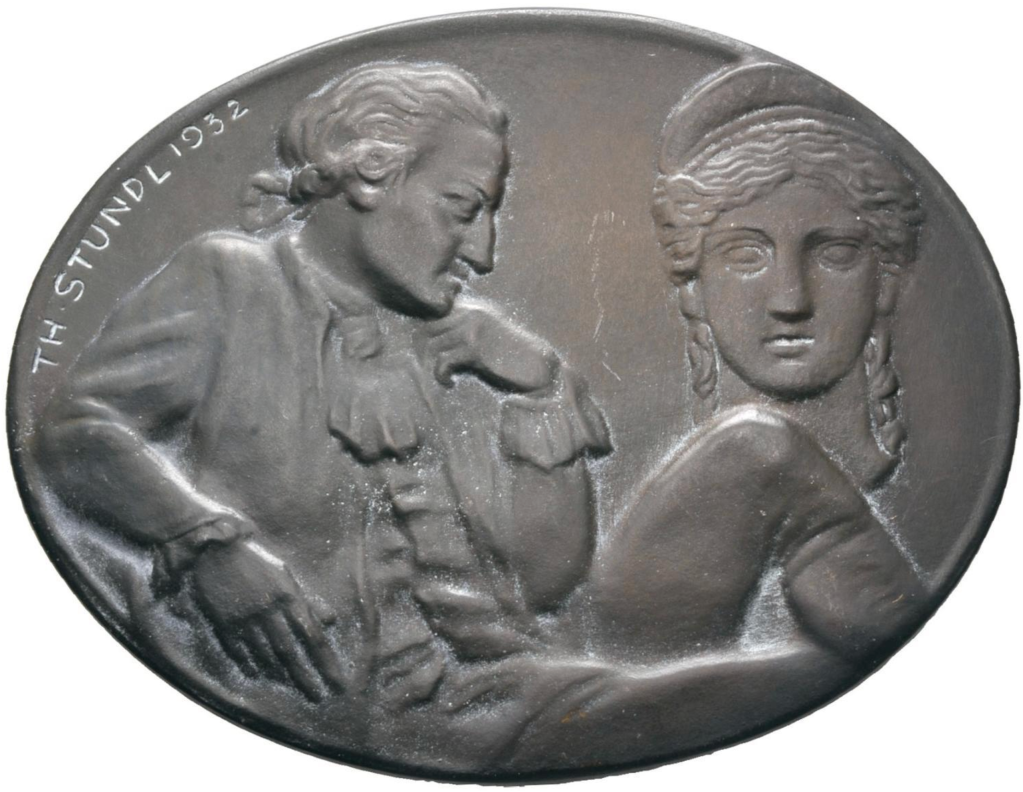

Uniface medal (1560) marking the 19th birthday of Francesco de’ Medici (1541-1587). Credit: Emporium Hamburg.

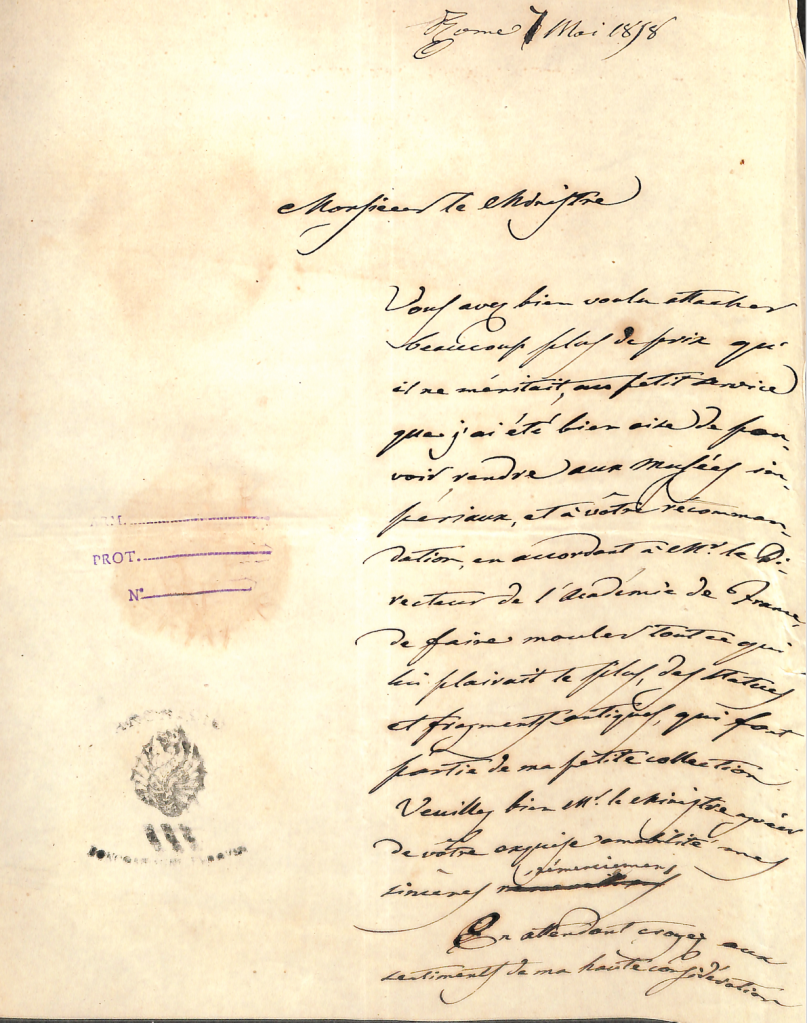

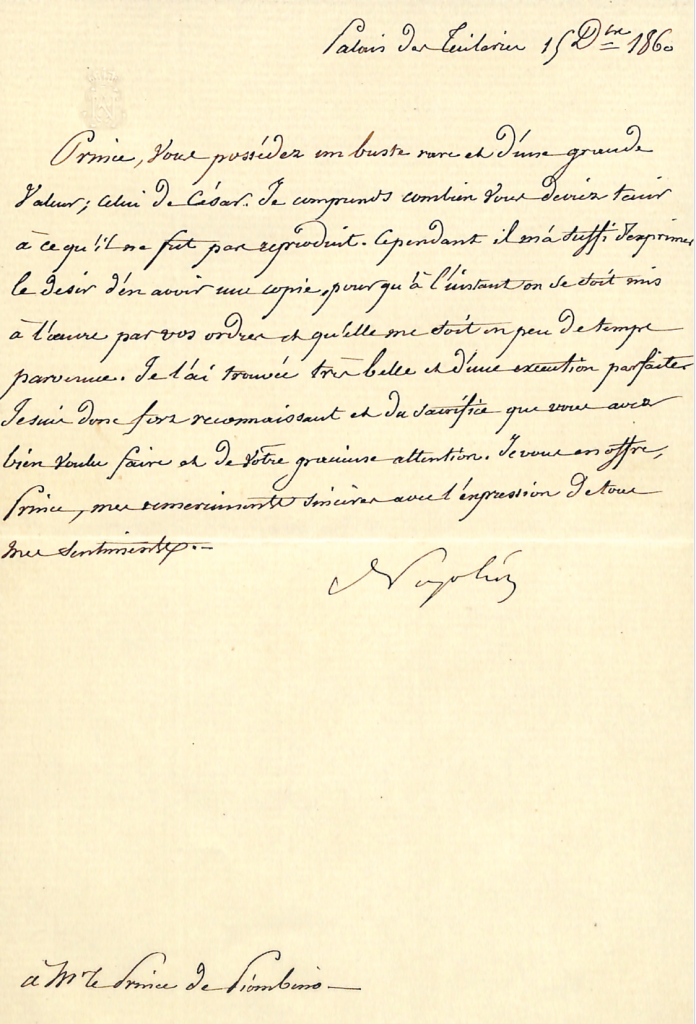

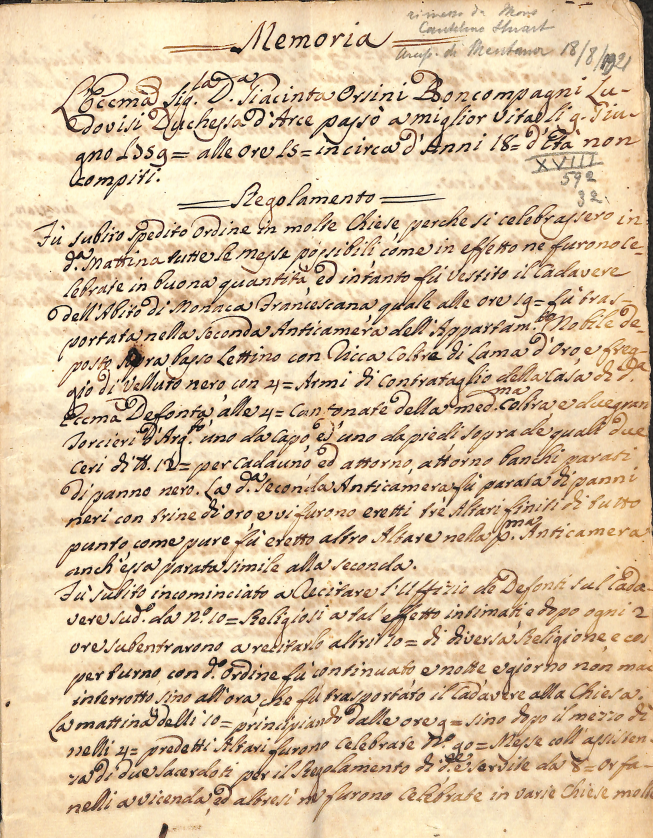

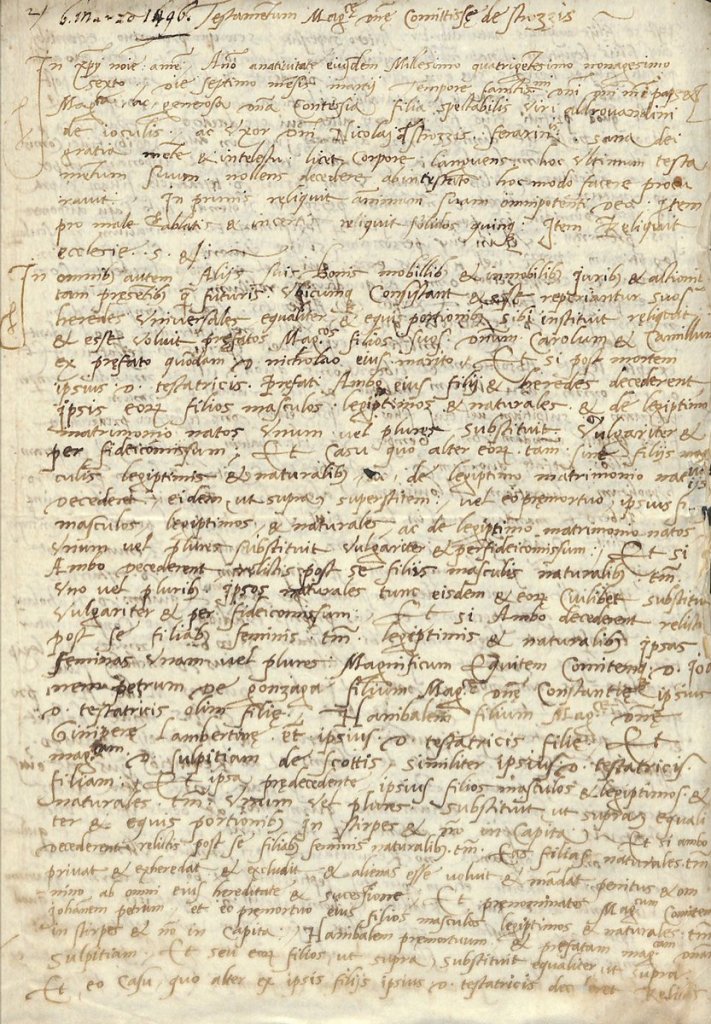

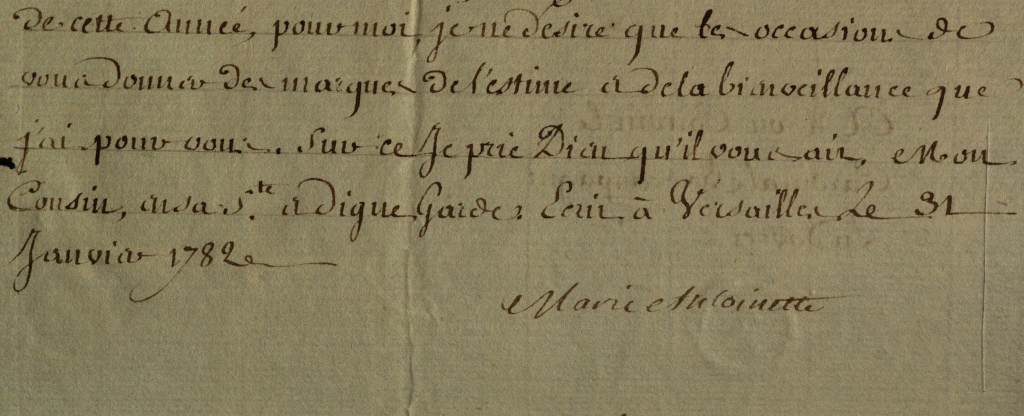

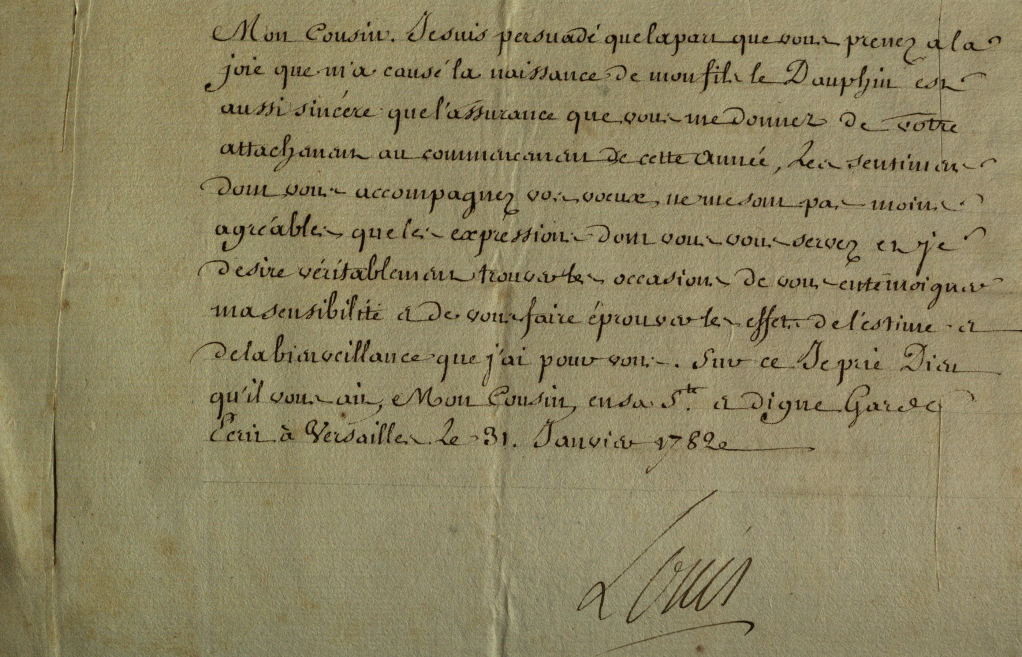

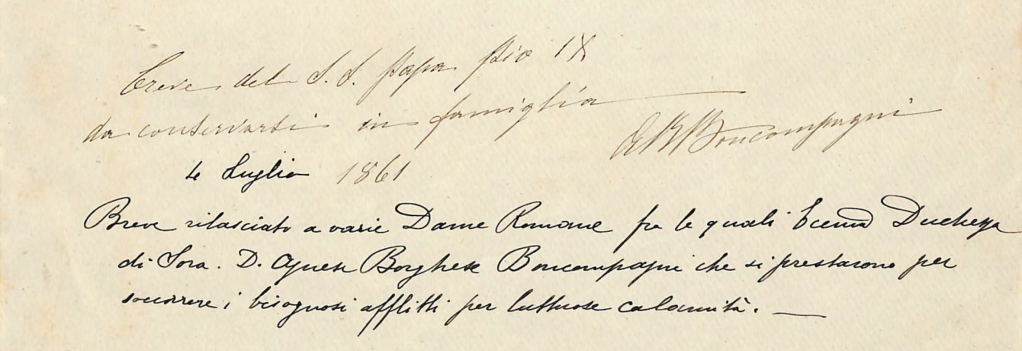

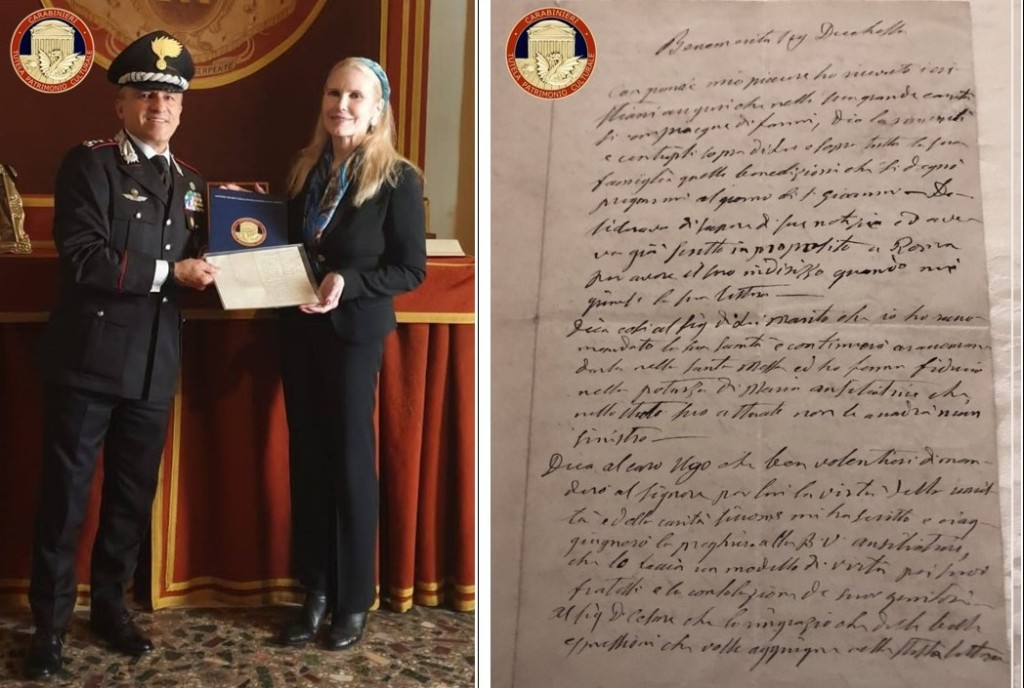

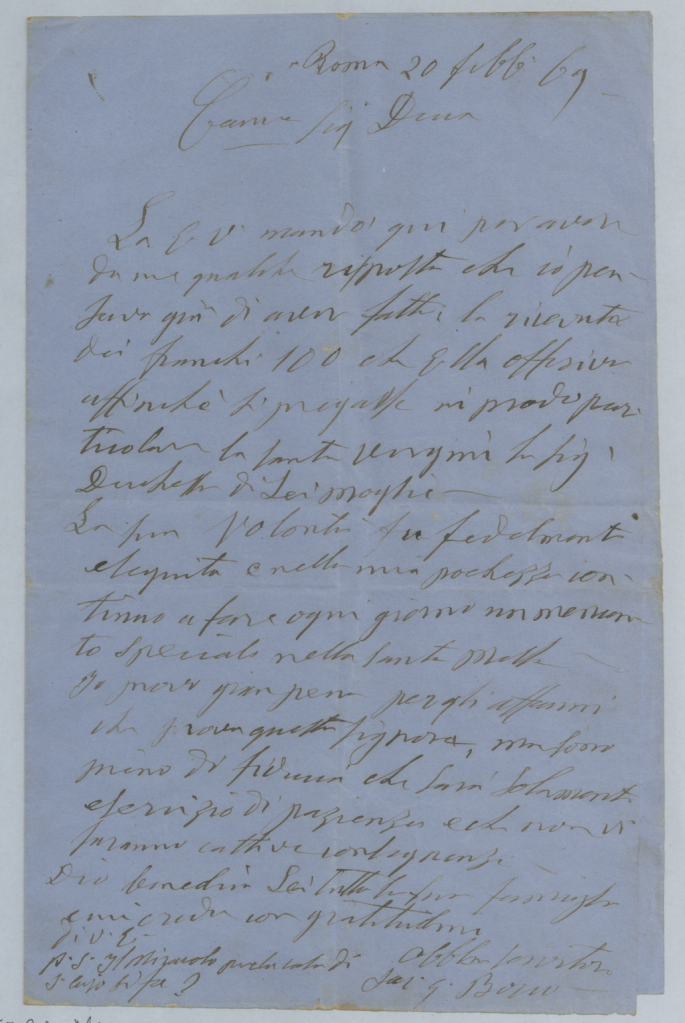

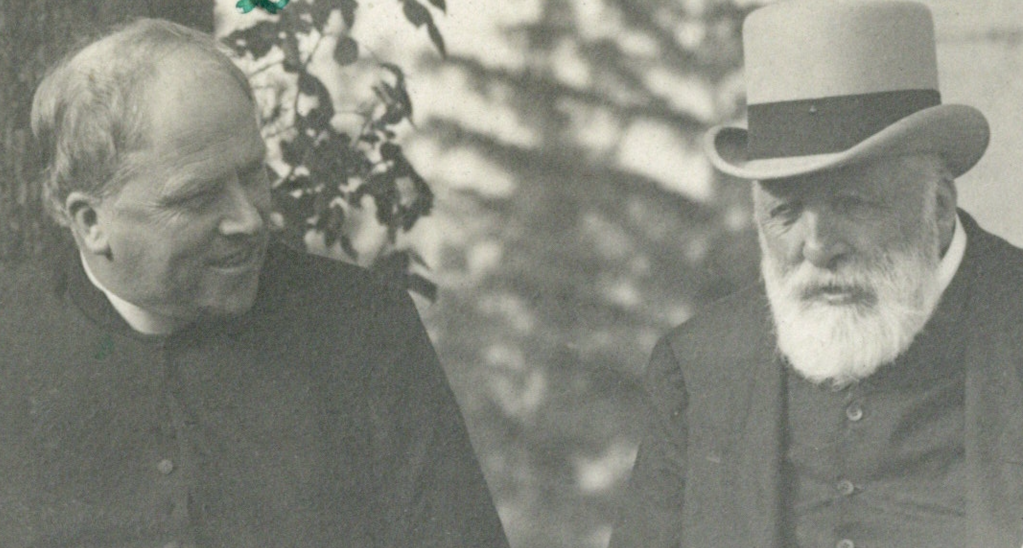

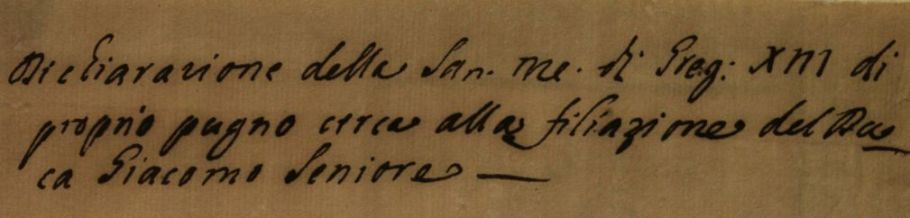

The first we hear that Bishop Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi actually had buried part of his collection of antiquities is five years after his death, early in the year 1569. In the first months of that year, the bishop’s relative and former patron Cosimo (I) de’ Medici—now elevated to Grand Duke of Tuscany—took an interest in the Pincio statues on behalf of his own sons Francesco (1541-1587) and Ferdinando (1549-1609).

The story of these young men is a familiar one. Francesco was to succeed his father as Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1574. On his death in 1587, his younger brother—a cardinal since 1563, at age 13—resigned his position and ascended the throne as Ferdinando I.

Agnolo Bronzino (1559), portrait of a young Ferdinando de’ Medici (1549-1609). Credit: Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Mansi

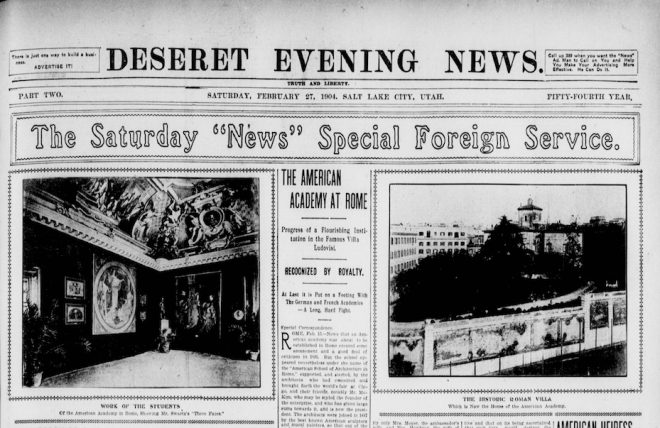

Ferdinando was also (since 1560) a precocious collector of sculptures, aided by Cosimo Bartoli, Alessandro Valenti, and above all Giovanni Ricci, Cardinal of Montepulciano. It was Ferdinando while still cardinal who created the grand Villa Medici on Rome’s Pincio hill, in the year 1576.

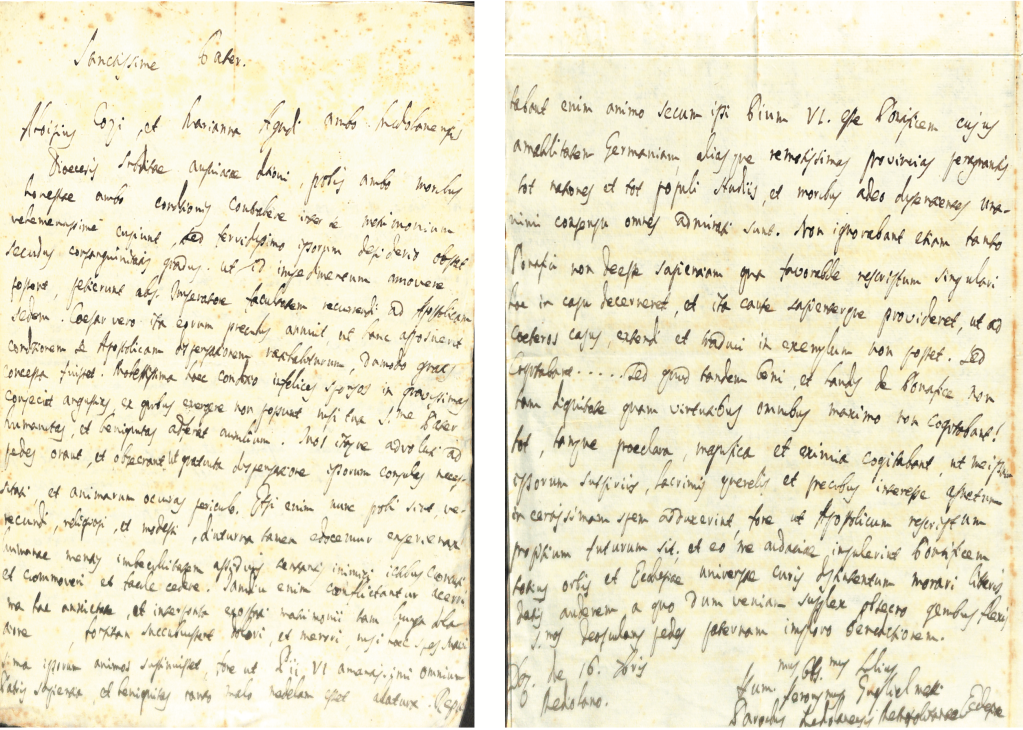

The situation in 1569 was that Sigismondo de’ Rossi had offered his deceased uncle’s entire sculpture collection to the Medici. But there were complications in conveying the gift, for the pieces had to be recovered from three different locations.

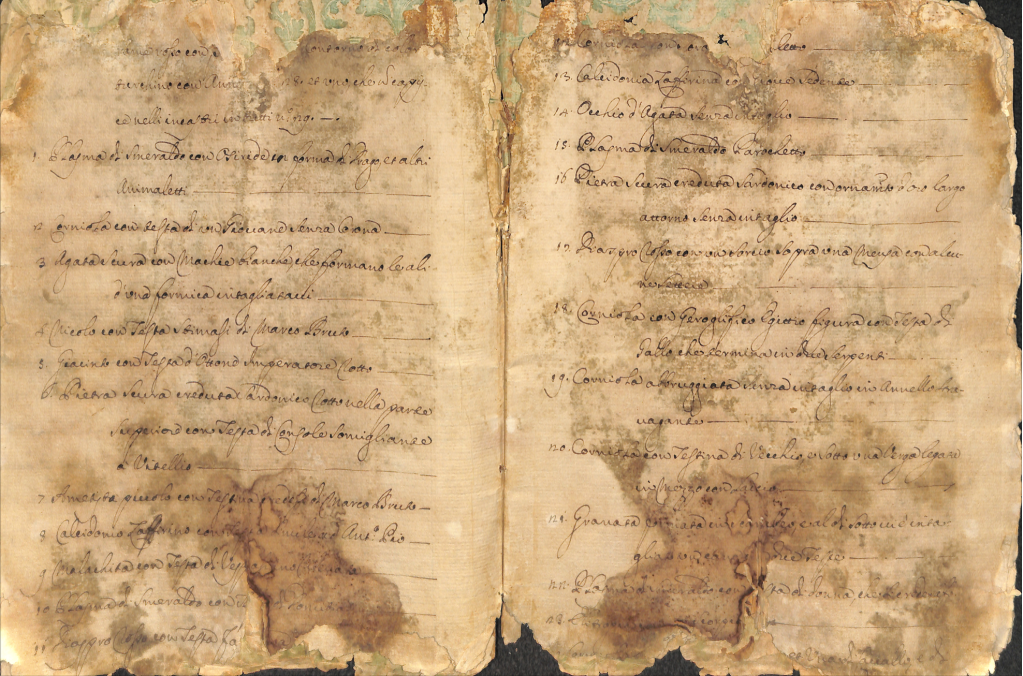

One part of the bishop’s collection was at his final residence, his Tuscan villa Il Barone. That was easy. A second part was in Rome, in the possession of a friend from Parma, the writer, art collector, and casual bishop Girolamo Garimberto (1506-1575). An undated inventory for that survives, detailing about 100 works, virtually all ancient or on classical subjects. When the Medici agents attempted to recover the pieces, fully 34 of the items on the list could not be found.

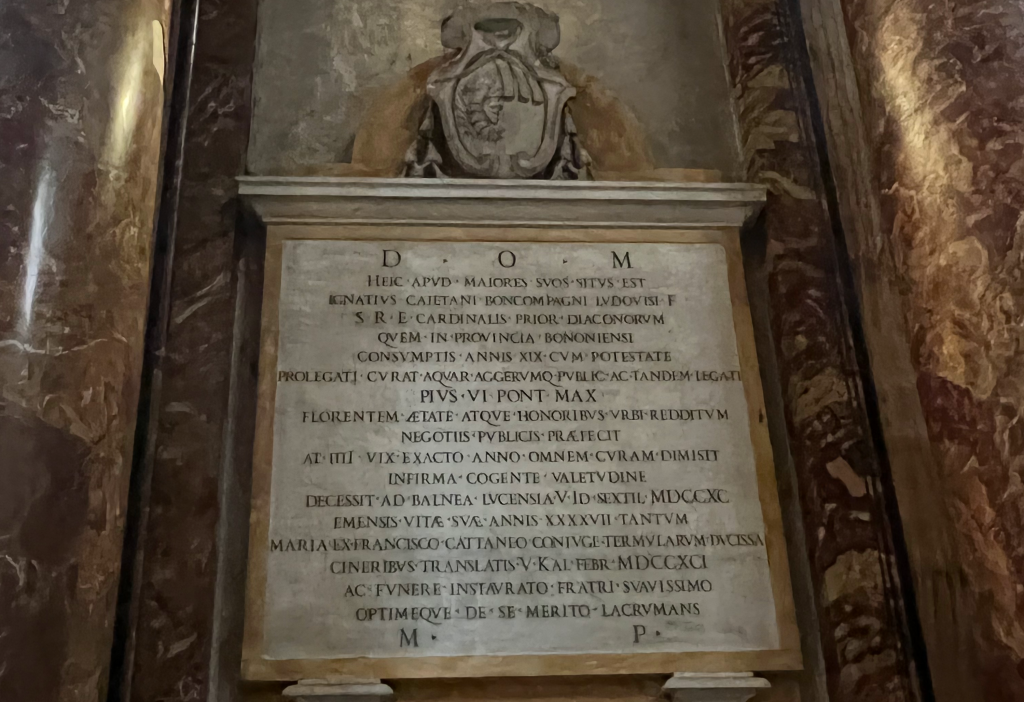

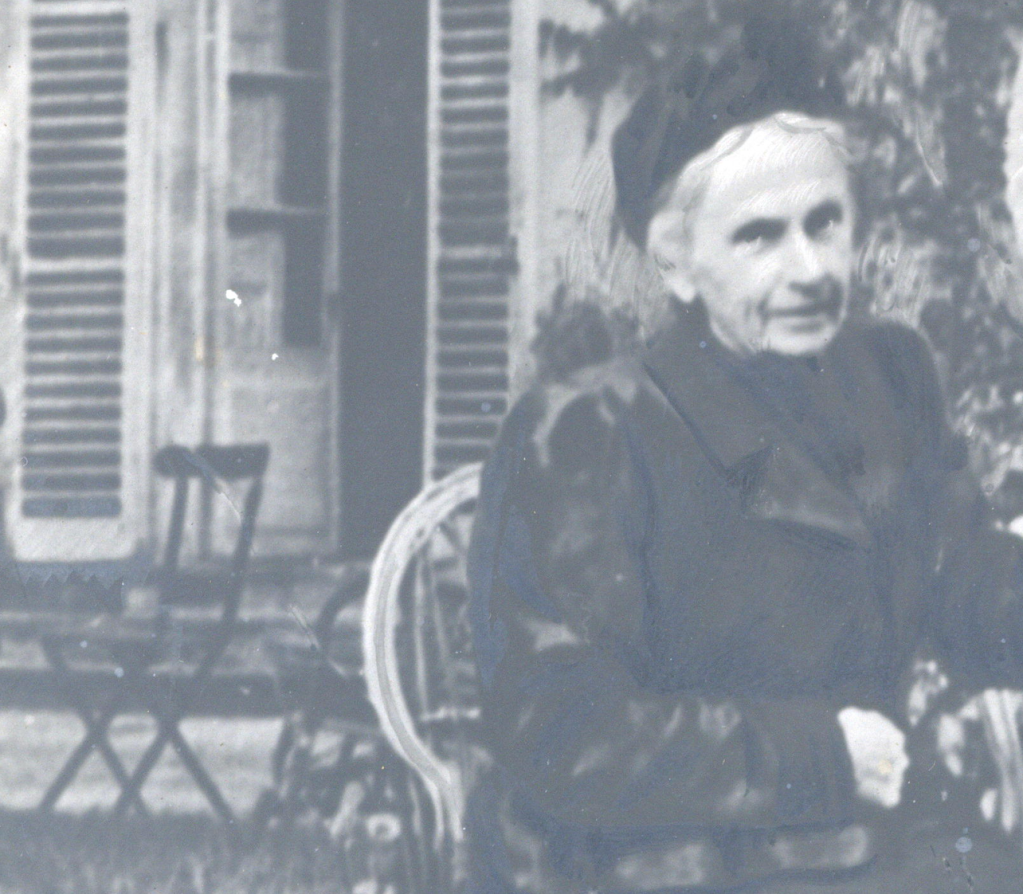

S Giovanni in Laterano, Rome: funerary monument of Girolamo Garimberto (1506-1585). Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

A glance at the Garimberto inventory reveals something of the shape of Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi’s collection.

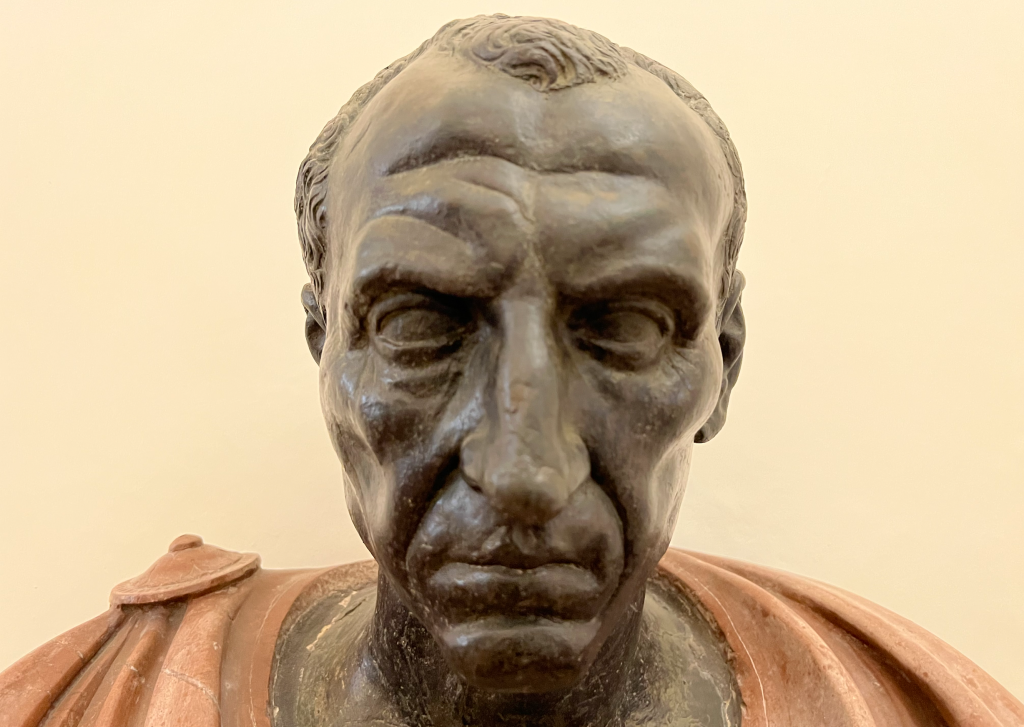

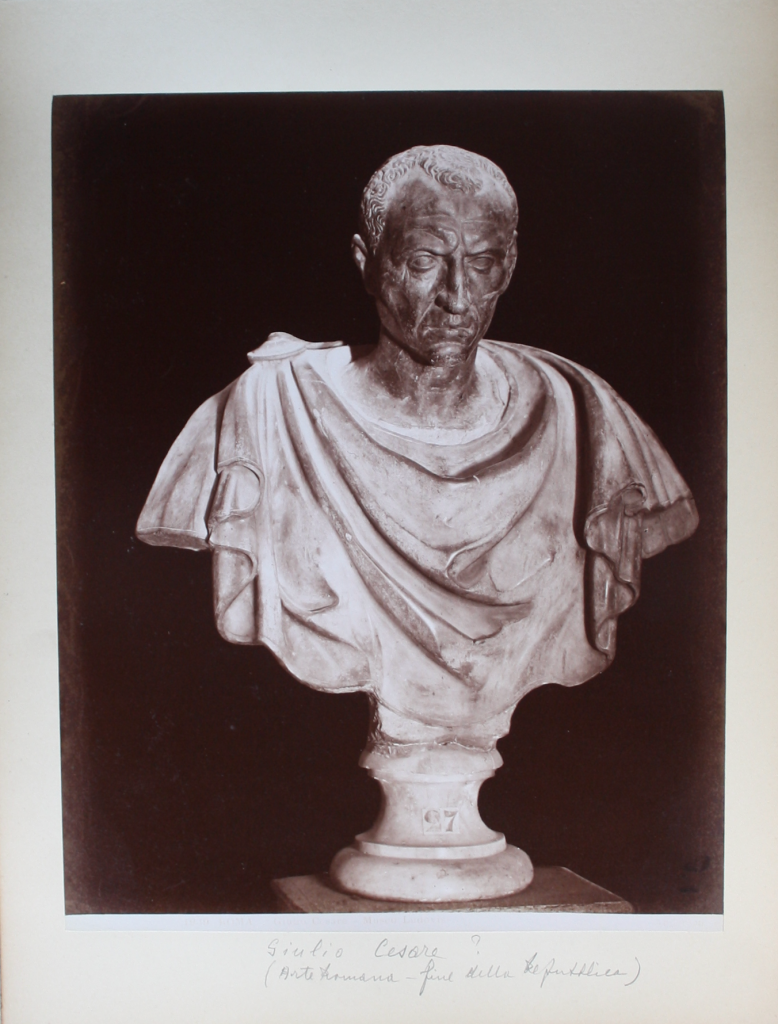

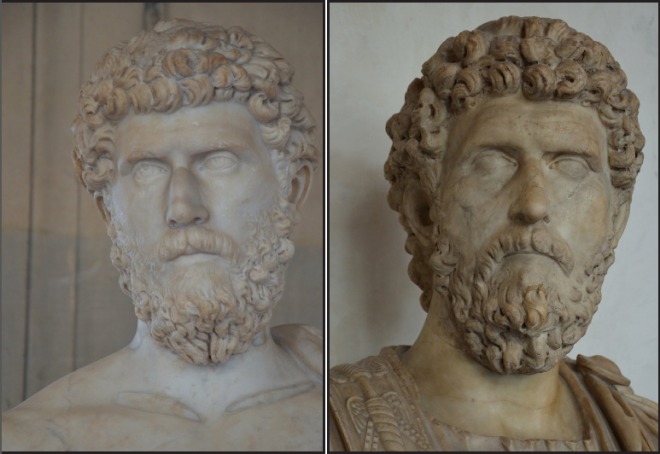

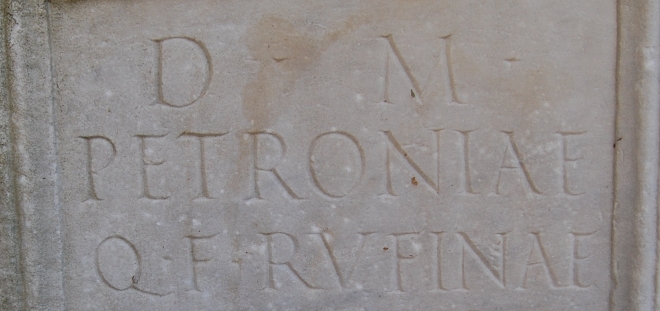

Portraits of Roman figures, especially emperors, predominate. These include sculptures identified as “Martius” (?), “Scipio”, “Brutus”, and “Julius Caesar”; also Augustus, “Marcellus”, Claudius, Vitellius, and “Julia”; Trajan and Hadrian (two of each, plus “Sabina” and Antinous); Antoninus Pius and Faustina (two of the latter), Marcus Aurelius, and Lucius Verus; Septimius Severus, Caracalla (two), Geta, and “Julia Mamaea”; also “Macrinus”, Commodus, and Gordian I, as well as a possible “young beautiful Gordian torso”.

A good number of these sculptural portraits are marked as modern works: the “Scipio”, Augustus, “Marcellus”, the Trajans and Hadrians, one of the Faustinas, and the Geta.

Note is also made of a “Pyrrhus”, “the philosopher Chrysippus”, and a “Cleopatra”, plus “a beautiful Greek woman’s head”. There is also an intriguing reference to the depiction of “unique Sabellians”—here one assumes the ancient Italic people of the central Apennines.

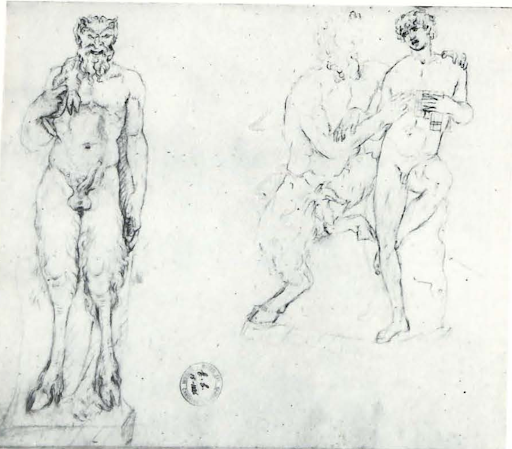

Then there are two ancient sculptures of Venus, as well as antique pieces identified as mythological figures: Orpheus, Ganymede, and Meleager. Plus an “intact Satyr with a little horn”, a “beautiful Satyra”, and an “intact Silenus”.

Finally, there is ample reference to incomplete or fragmented sculptures in Garimberto’s possession in Rome, like a bust without a head, heads without busts, a half-relief carving of a child, a half-column of alabaster, “stone tablets with two feet” (?), a small torso, a leg, and miscellaneous pieces that could not be found.

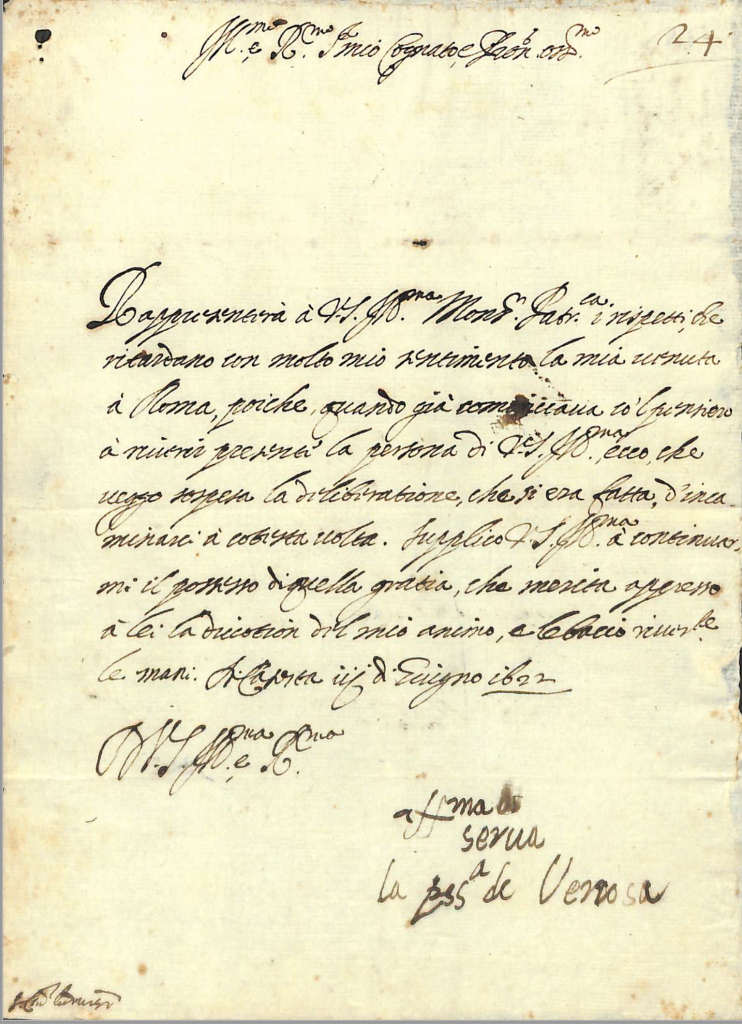

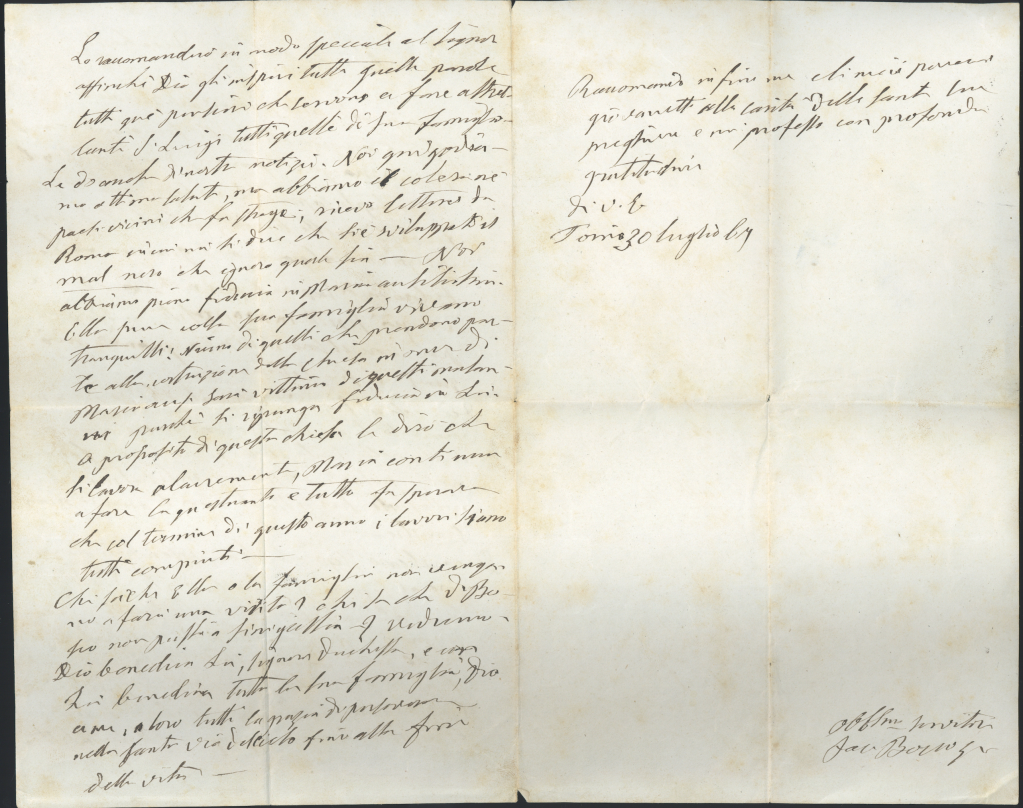

As for the third and final part of the de’ Rossi collection, it was buried in his former Roman vineyard, now owned by Cardinal Flavio Orsini. These are said to be comparable in quality to those found at Garimberto’s Rome residence, and not many in number.

Indeed the Medici started digging for the buried treasure in Rome already in late January 1569—said to be an expensive and uncertain proposition. The issue was that Girolamo Garimberto apparently had a list of sculptures hidden on the Orsini estate, but only a general map of where to look.

On 25 March 1569, Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici summed up the state of affairs to his elder brother Francesco: “the statues of Count Sigismondo that are in the hands of Garimberto are at our disposal; the few others, no less good, which remain in the Orsini vineyard, will be obtained with difficulty, although the Abbot [= the vineyard’s owner, Cardinal Flavio Orsini, abbot of Subiaco] will make efforts to release them.”

Palazzo della Carovana (Pisa): stemma of the condottiere Sigismondo de’ Rossi (1524-1580). Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

By now, Cosimo de’ Medici had taken a direct interest in his sons’ division of the statues, charging one Stefano Lalli to supervise the task. On 16 April 1569, Lalli reported to Francesco de’ Medici (evidently in Florence) that the Garimberto portion of the collection was ready for distribution, and his brother Cardinal Ferdinando was eager to get his share. But “the antiques buried in the vineyard that belonged to the Bishop of Pavia” on the Pincio were still inaccessible. Indeed, the vigna’s current owner, Cardinal Orsini, was contemplating selling the land, introducing a further complication.

Lalli emphasizes to Francesco the need for absolute secrecy in this matter: since “in this inventory [i.e., the one provided by Garimberto] there is the notice of the place where the said antiques are buried in the vineyard, it seemed to me to advise His Most Illustrious Lordship that it would be good not to disclose it to anyone else, so that it may not be known by others, but only by Your Excellency and His Most Illustrious Lordship [i.e., Ferdinando], who told me that he will be informed about this and that he will not reveal it to anyone.”

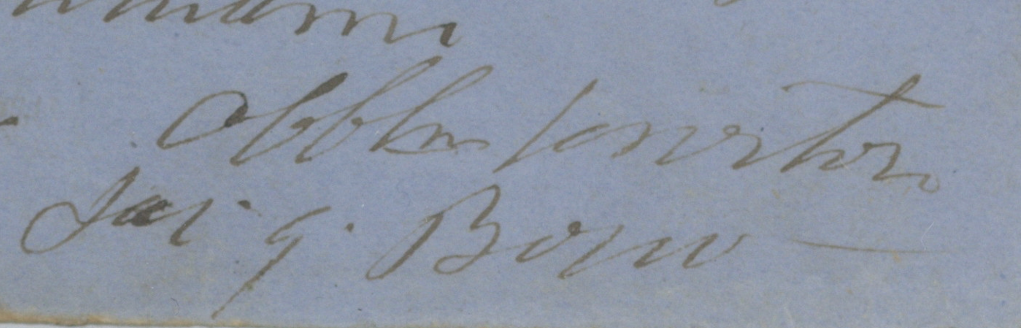

A week later, on 24 April 1569, Stefano Lalli could report to Francesco de’ Medici major progress in the treasure hunt. He writes that Garimberto had unearthed “all these heads and other antiquities that were buried by the Bishop of Pavia in his vineyard”. Plus he possessed a head of the Gallicola [= Caligula], five times larger than life, which, he said, was given to him by the members of the Rossi family, showing a letter they wrote to him.”

In the event, we learn from Stefano Lalli that Cardinal Ferdinando had instructed him and Diomede Lioni “to verify and identify all these antiques together, following the inventory that Your Excellency [i.e., Francesco] sent me”. The process involved significant confusion. True, many pieces could be recognized from the inventory of vigna statues, even given their poor maintenance. But others emerged that were not on the list. Lalli also flatly states that many of the pieces were junk. Still, Cardinal Ferdinando decided that there were enough worthwhile sculptures to send to his brother via the port of Civitavecchia, where a ship was waiting to transport that portion of the lot to Tuscany.

And with that, the work of digging on the Orsini vineyard apparently stops. “It seems to us”, reports Lalli, “that we have no other information about these antiques than what Monsieur Garimberto says, which should be taken in the manner he confesses.” He continues that “the other statues that are in the vineyard that are seen, have not yet been discussed or dealt with” pending the possible sale of the vineyard.

San Quirico d’Orcia, S Maria Assunta: commemorative marker for Diomede Leoni (1514-1577), founder of the Horti Leonini in that town. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

On 12 May 1569 the ship captain at Civitavecchia was still waiting orders whether to bring Francesco’s part of the de’ Rossi collection to Tuscany. So Lalli writes a request to the elder brother “to have the resolution of Your Excellency as to whether you are satisfied to receive the antiquities held by Monsieur Garimberto of Your Excellency and our Cardinal in the manner in which he wishes to deliver them, saying truthfully that those he has shown us are all that he has in the hands of Monsieur de Pavia, and so I believe it to be. However, because we do not find the complete correspondence [of sculptures] according to Your Most Illustrious Excellency’s inventory, Mr. Diomede Lioni and I resolved not to receive them without the will of our Cardinal, who, after hearing everything, instructed me to notify you.”

Evidently no prompt response arrived from Francesco, since by 20 May 1569 the ship had left for Tuscany without its intended cargo. So Lalli and Diomede Leoni made the division for the two brothers of the de’ Rossi statues in Rome, where they were to be kept for collection. We do not know when Francesco picked up his part and brought it to Florence; those destined for Cardinal Francesco likely remained in Rome.

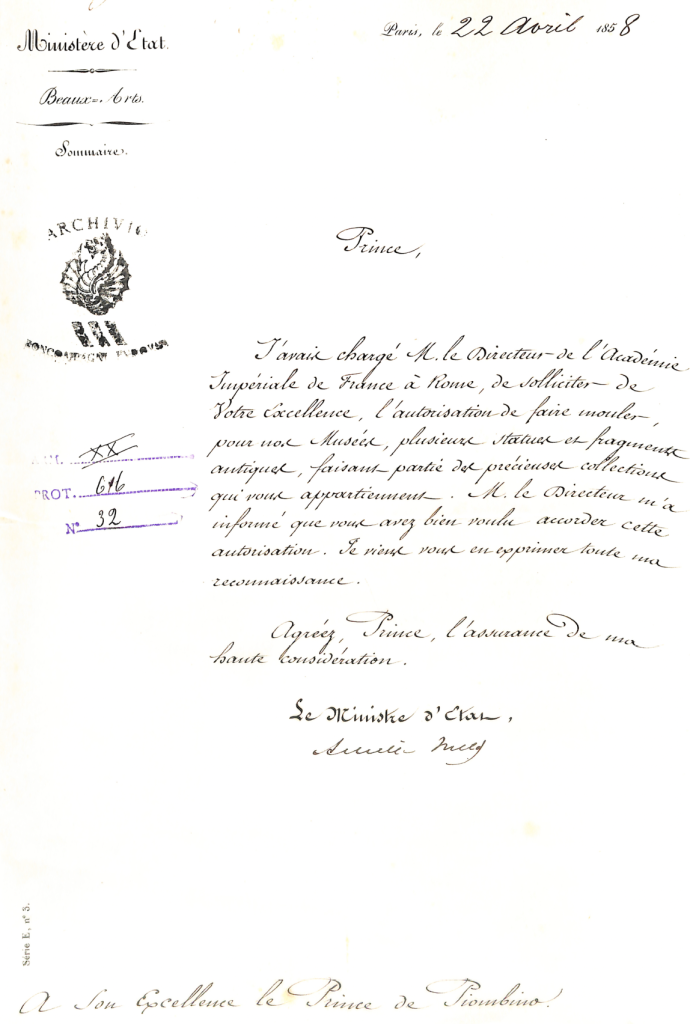

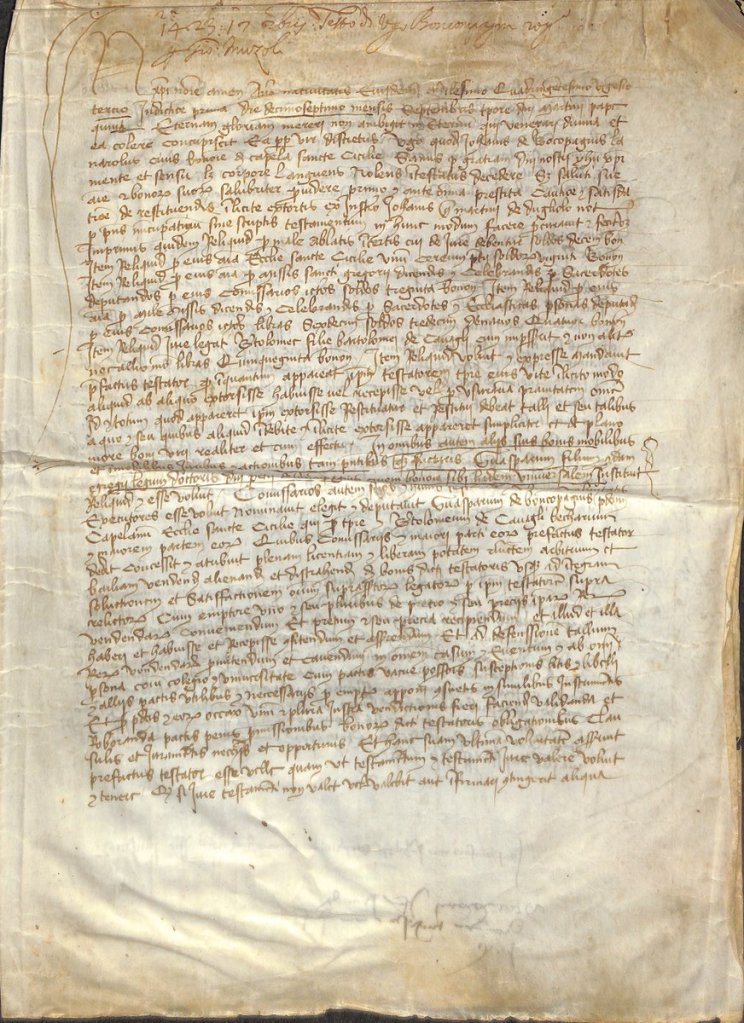

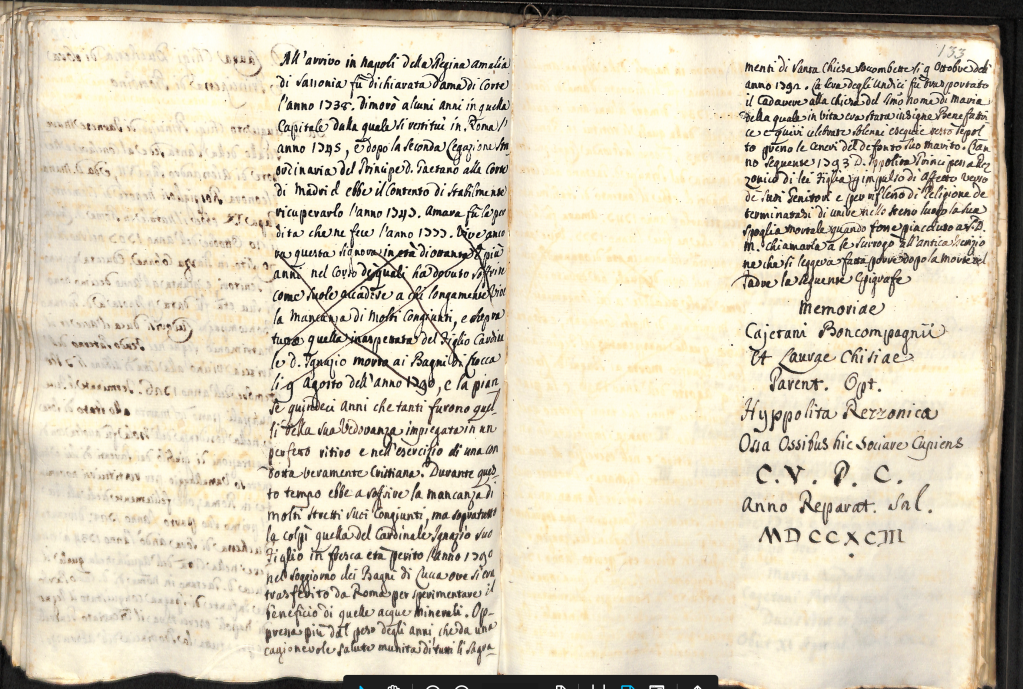

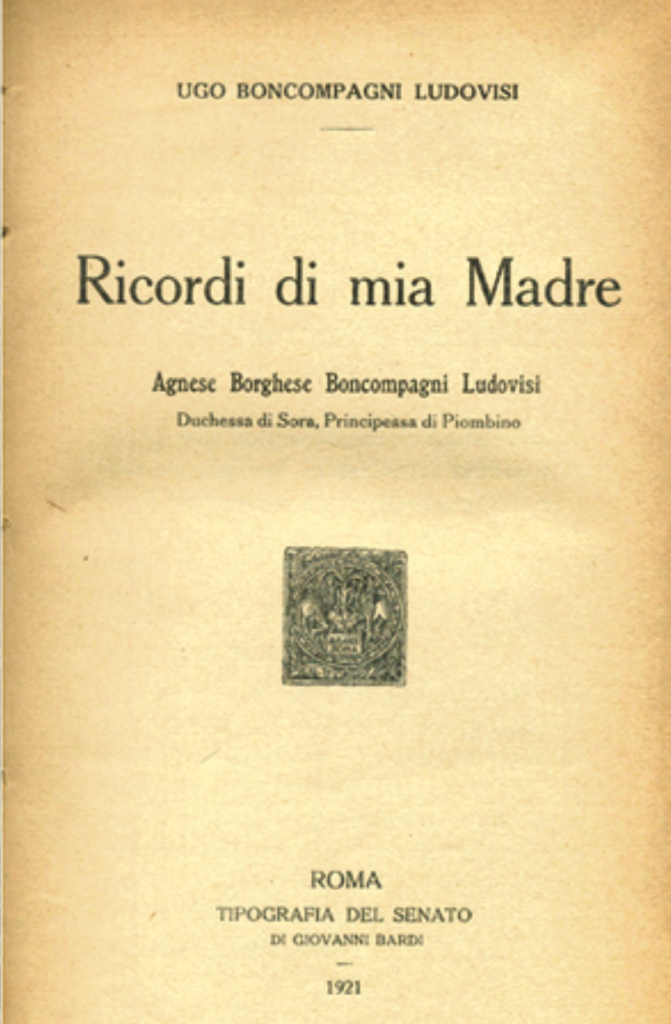

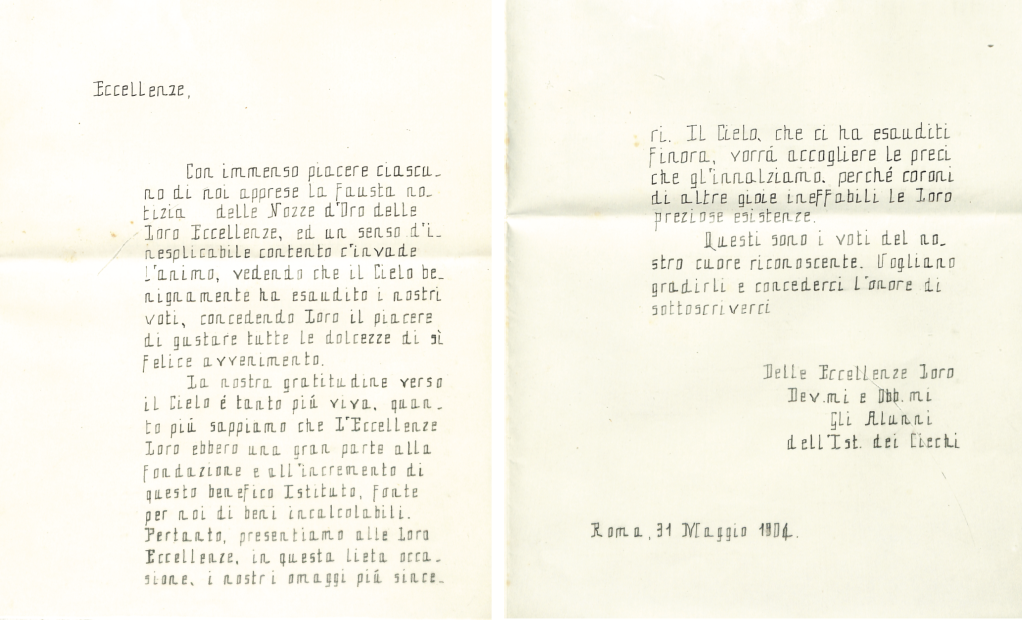

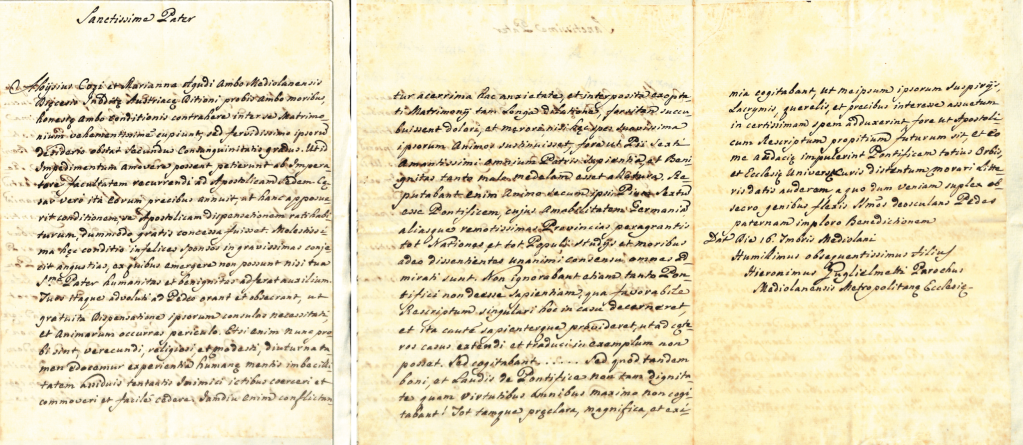

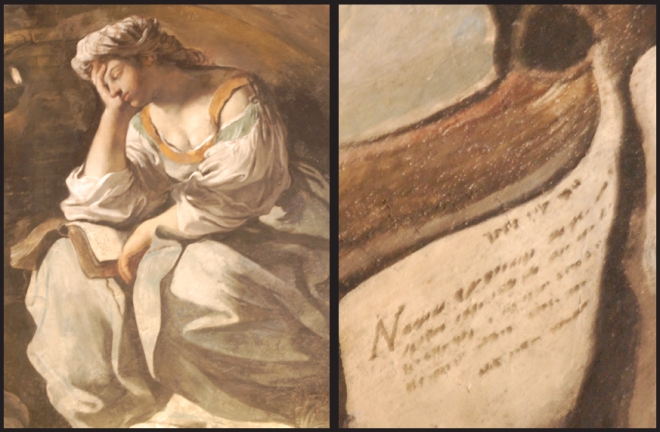

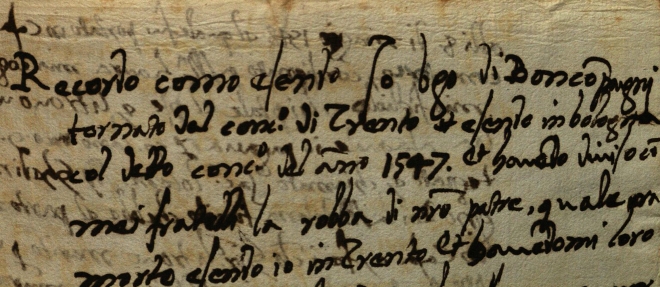

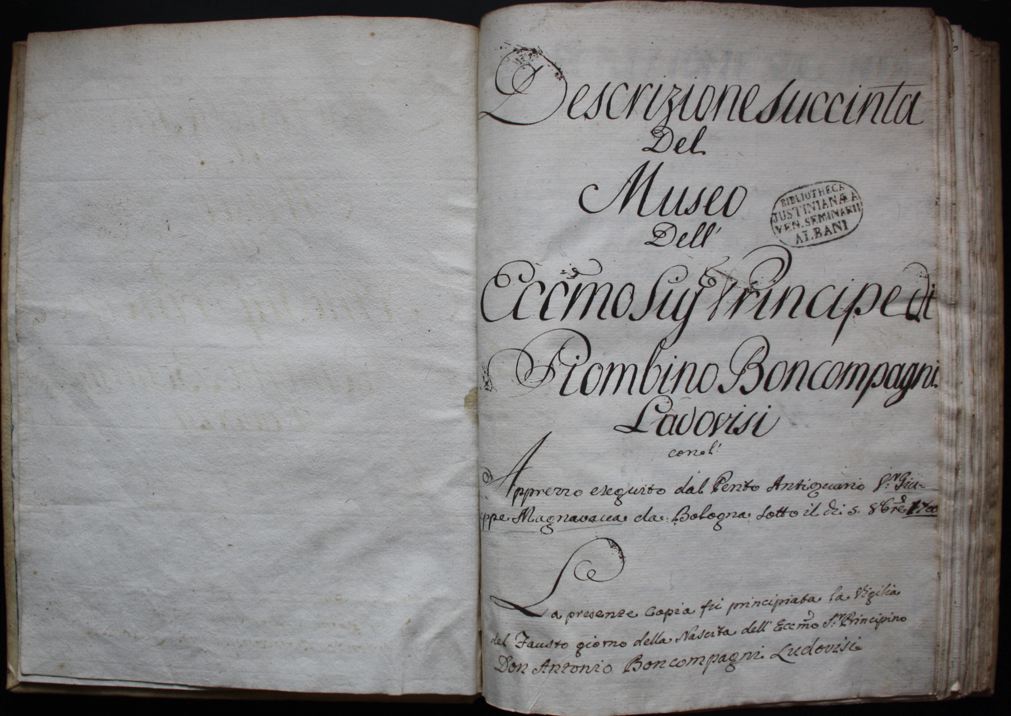

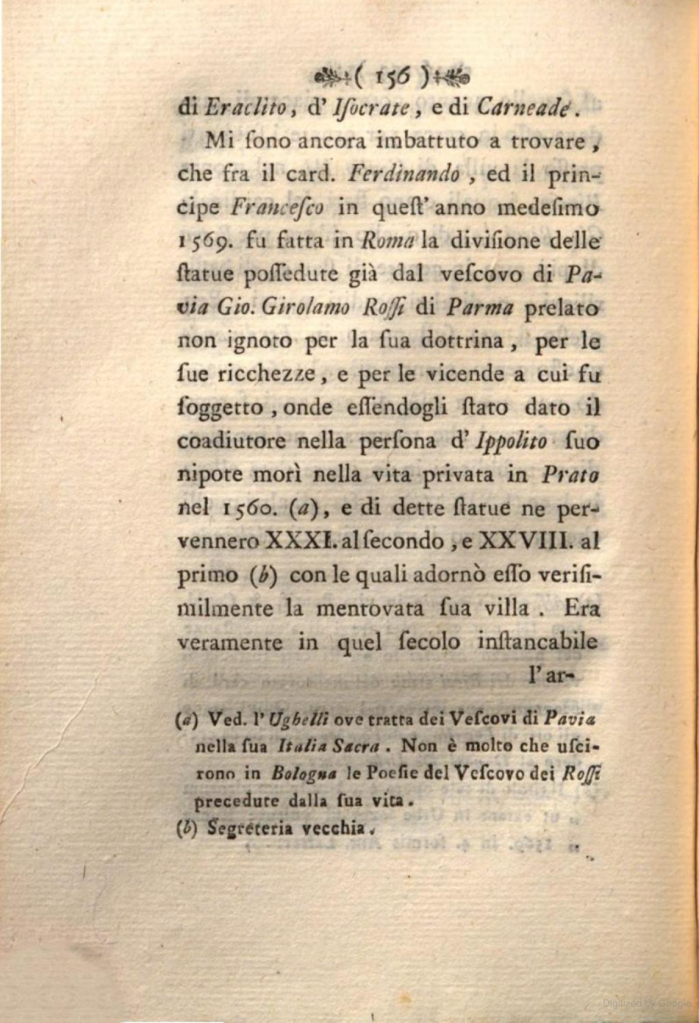

Excerpt from Giuseppe Bencivenni Pelli, Saggio Istorico della Real Galleria di Firenze (1779).

Writing almost a full two centuries later, in 1779, the Florentine antiquarian Giuseppe Bencivenni Pelli tells us “between Cardinal Ferdinando and Prince Francesco, in…1569, in Rome, the division was made of the statues already owned by the Bishop of Pavia, Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi of Parma, a prelate not unknown for his learning, for his riches, and for the vicissitudes to which he was subjected… and from these statues, XXXI went to the second and XXVIII to the first.”

If this report of a total number of 59 pieces is correct, the Medici brothers took possession of only a portion of the de’ Rossi collection. We have seen that Garimberto’s inventory of ancient and modern items approached 100, and it is uncertain whether that list encompassed also all the sculptures said to be buried in the vigna.

So where are we? It may be that this complicated tale in Medici records of the partial recovery and division of a 16th century sculptural collection buried on the Pincio has a certain relevance to the formation of the Villa Ludovisi. Can it be that Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, in the excavation work of 1621-1622 on his urban retreat, was able to find items buried by Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi that had eluded the Medici and for that matter the Orsini?

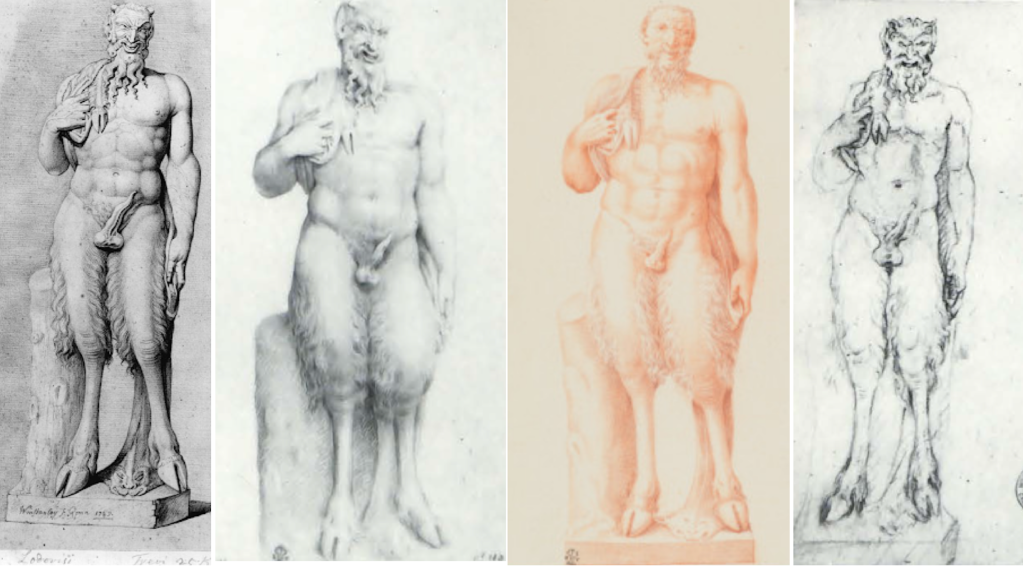

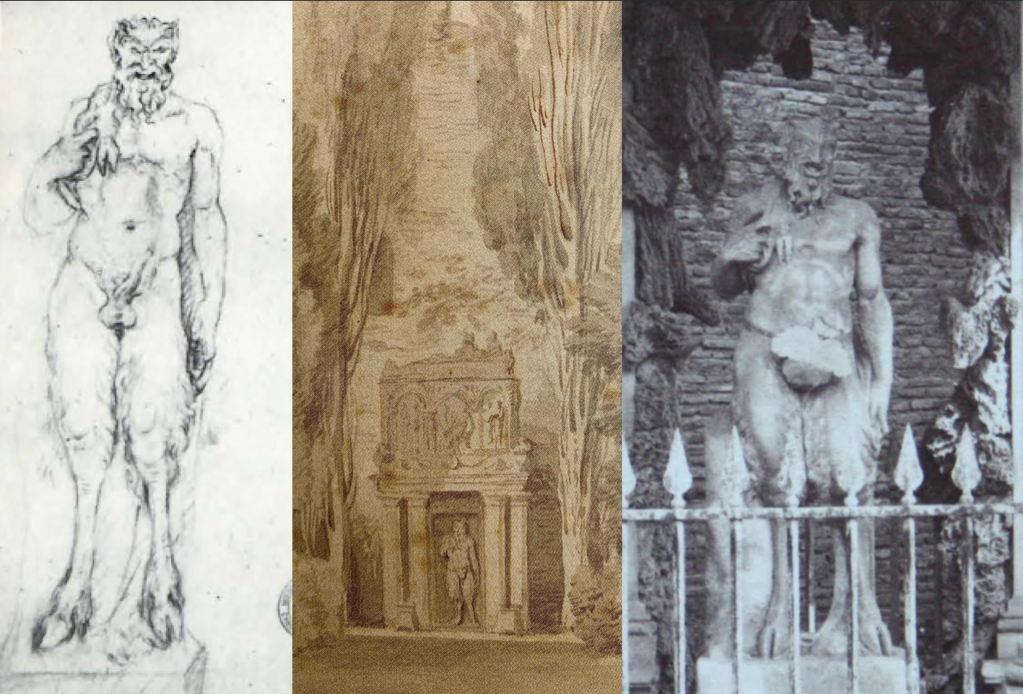

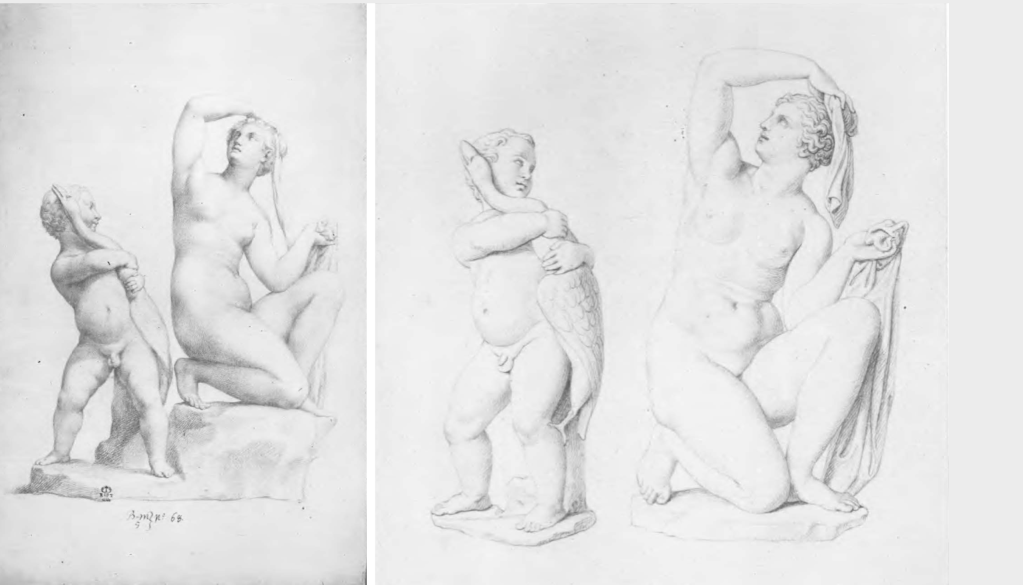

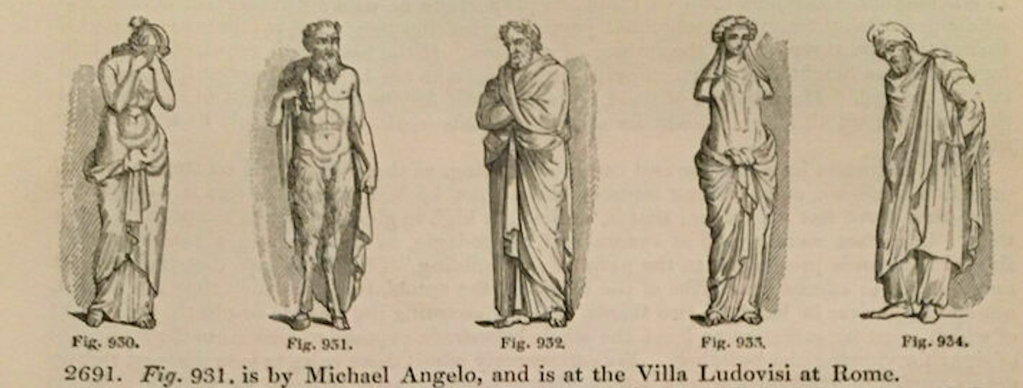

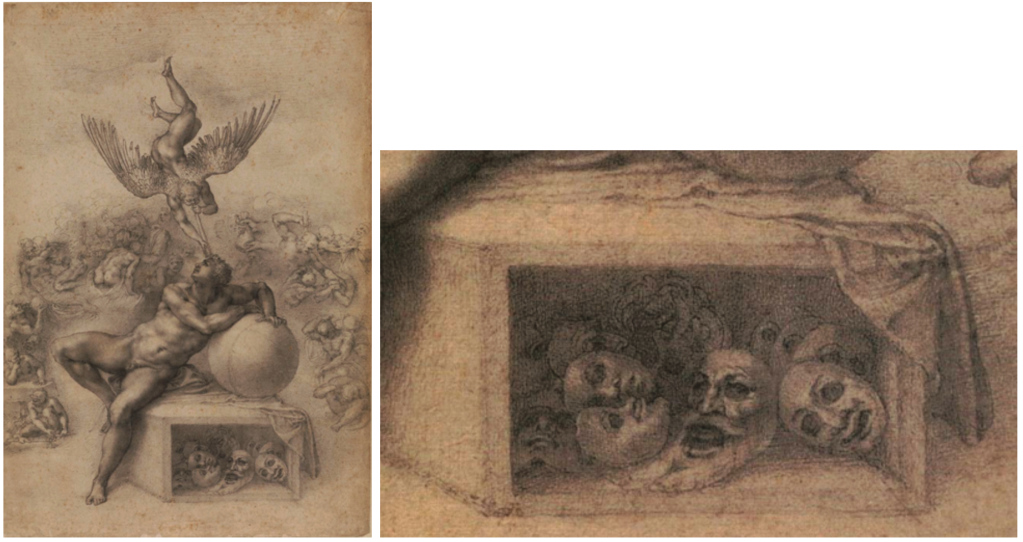

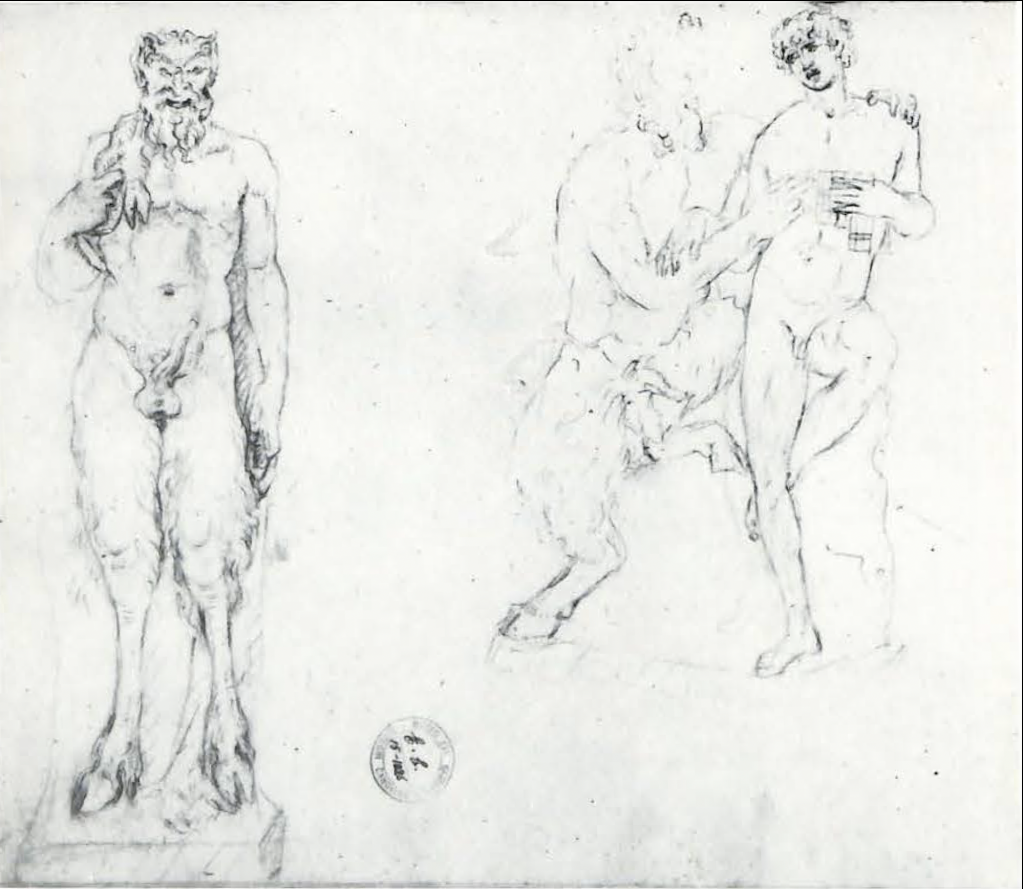

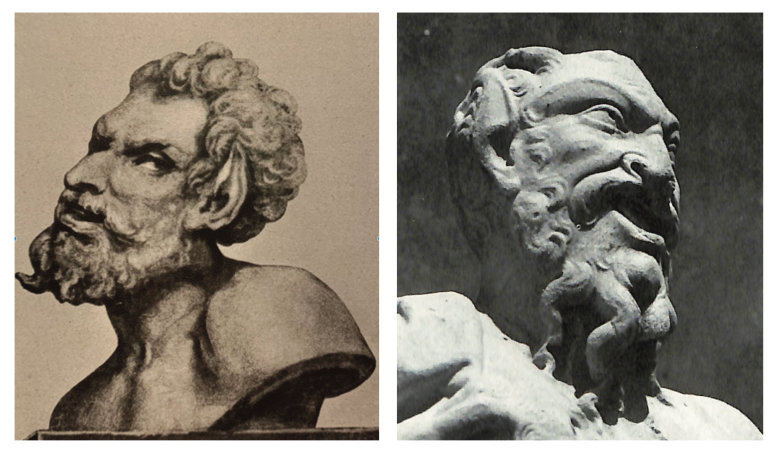

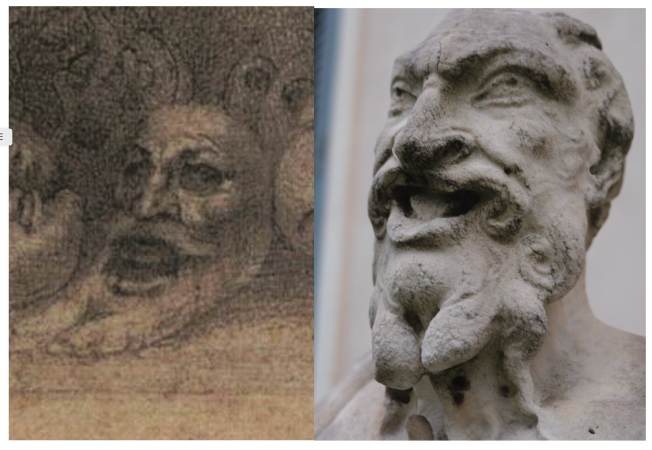

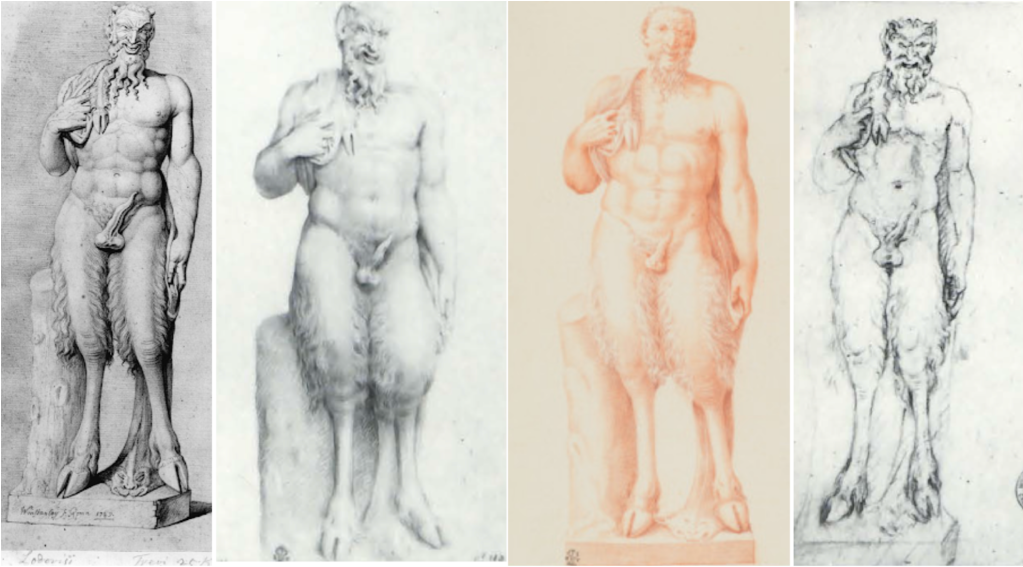

From left, depictions of the Ludovisi Pan by Hamlet Winstanley (1723); Pompeo Batoni (ca. 1727-1730); Bernardino Ciferri (ca. 1710-30), and Antonio Canova (1780).

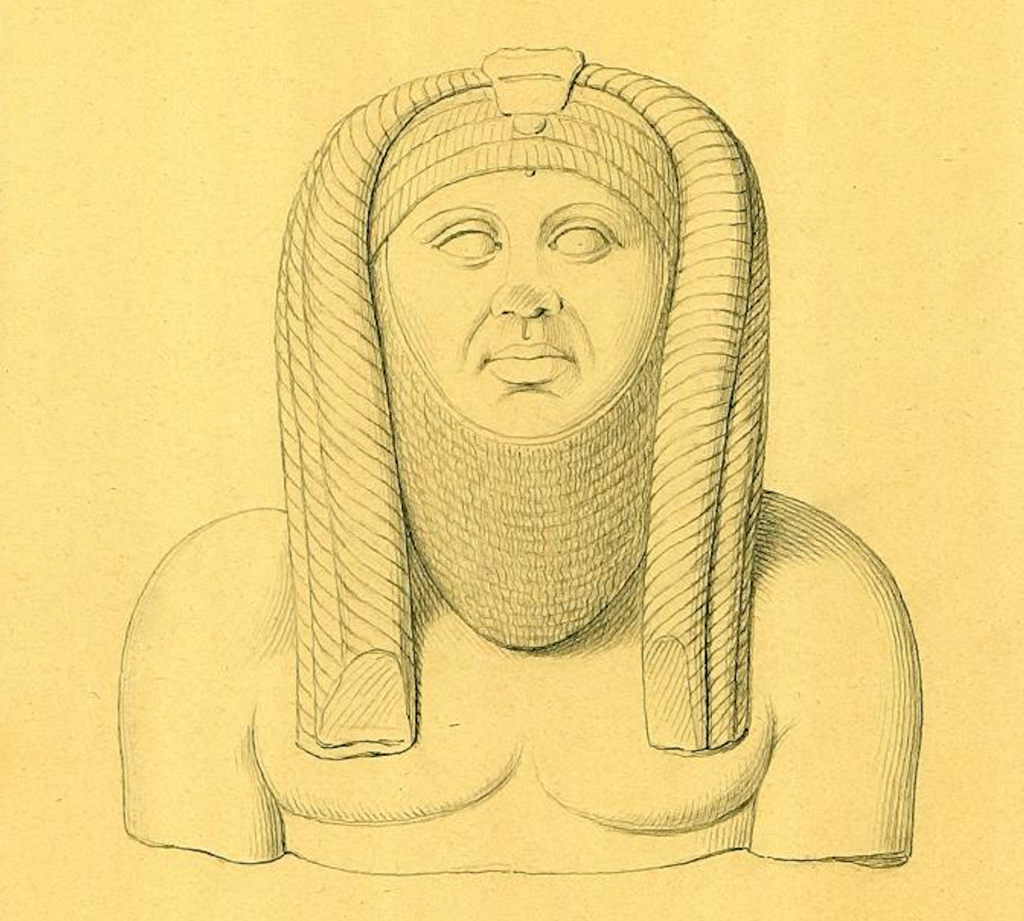

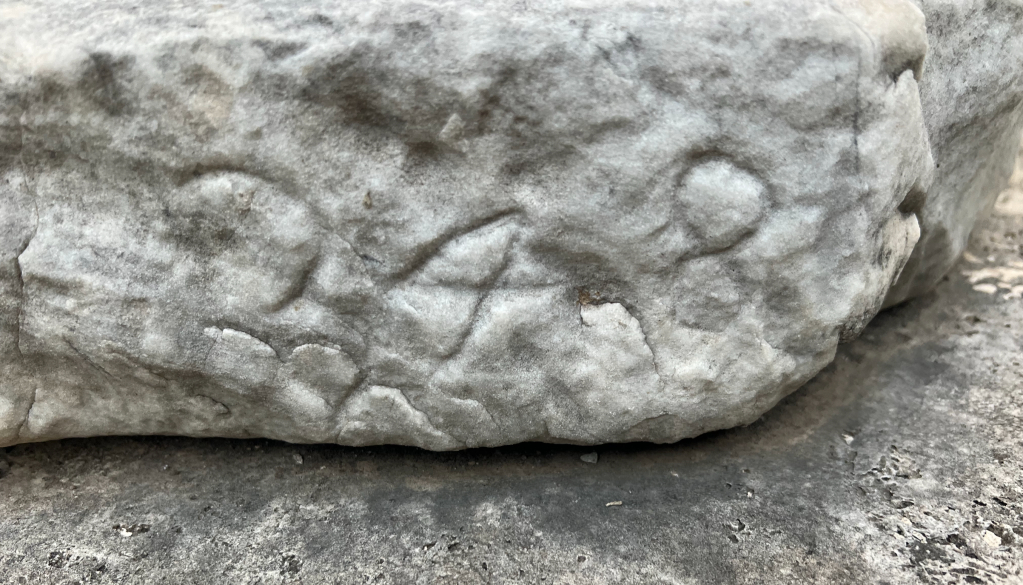

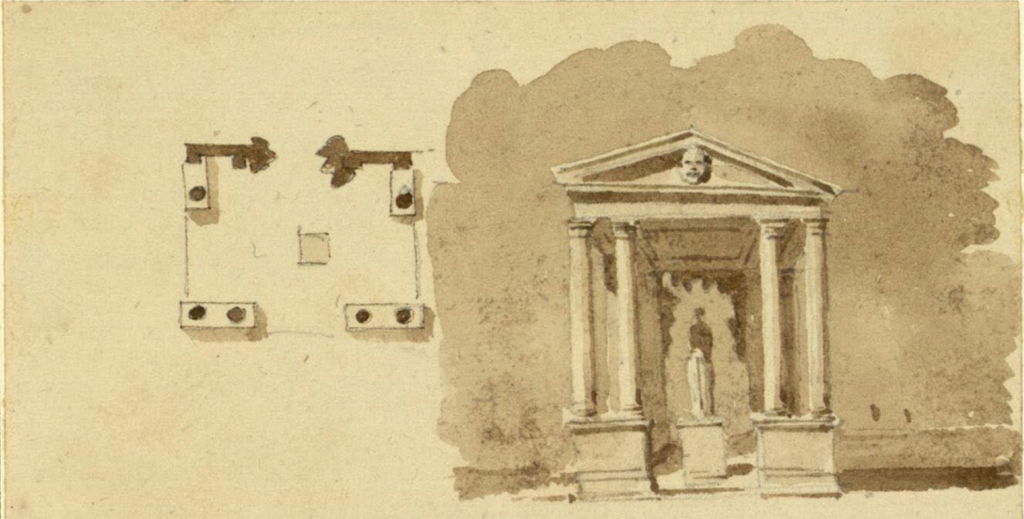

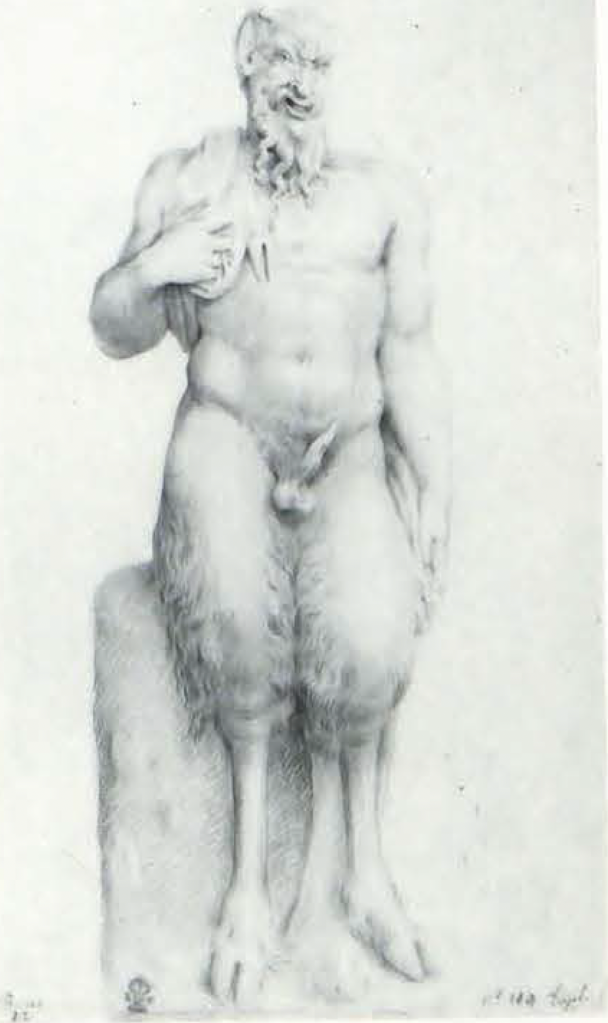

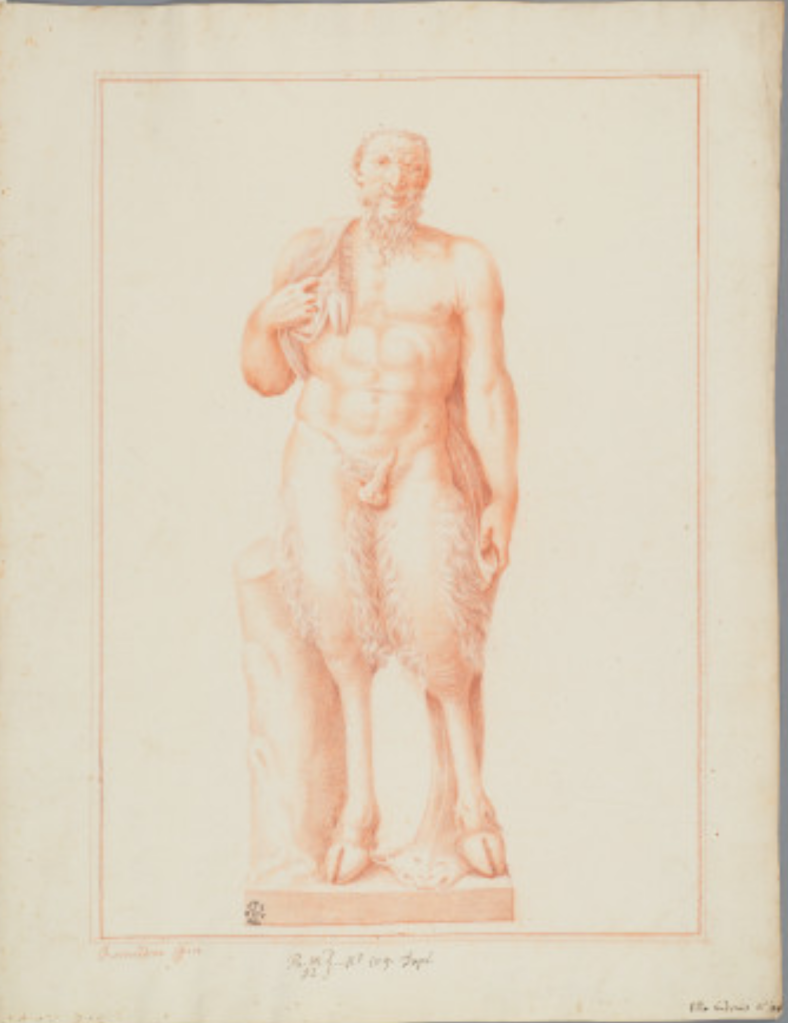

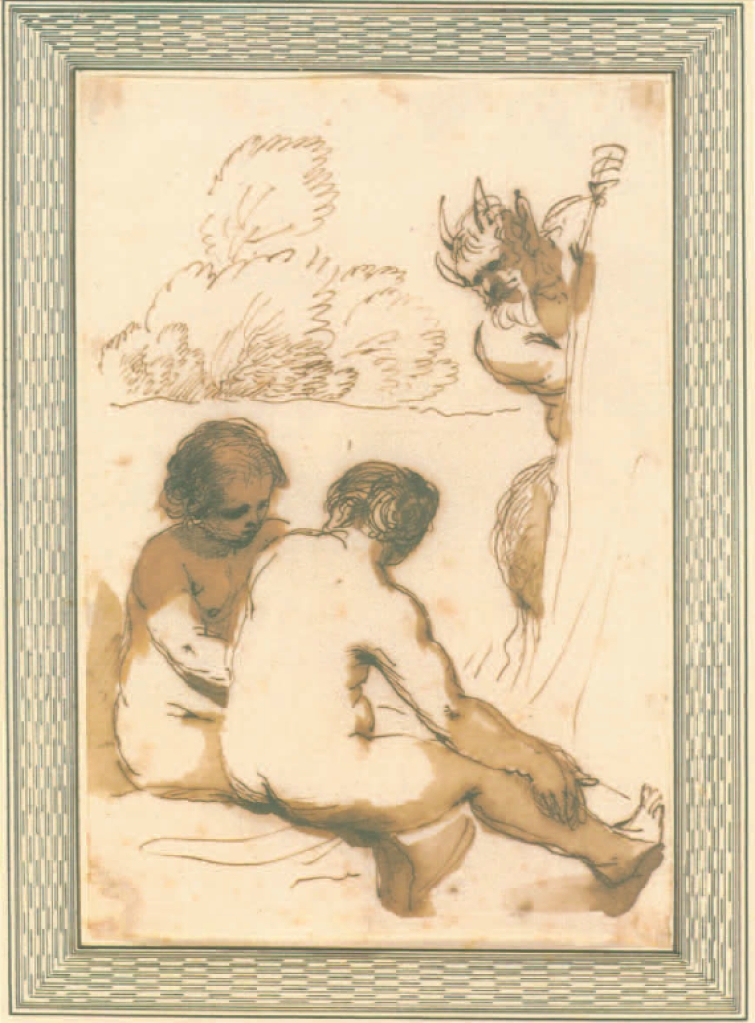

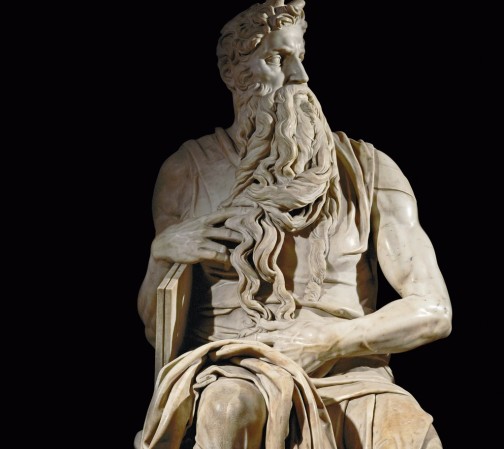

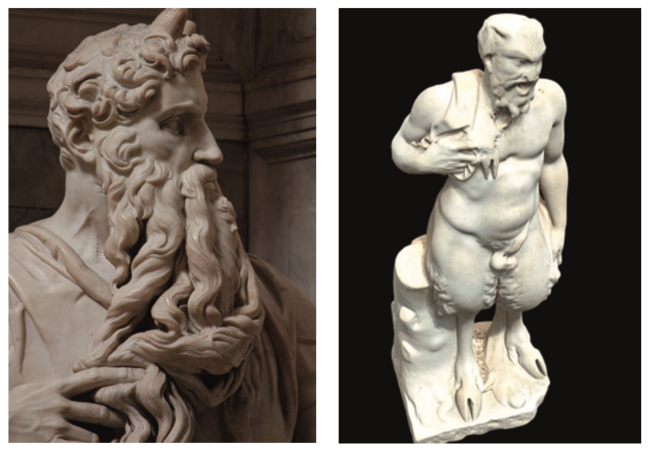

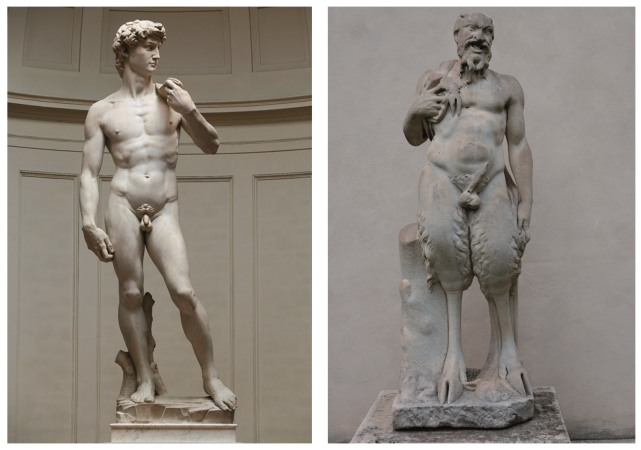

Following this hypothesis, one work of art immediately suggests itself as an ex-de’ Rossi piece found on the grounds: the full size sculpture of Pan that somehow enters the Ludovisi collection by 1633. As Hatice Köroğlu Çam has shown in a four-part series of articles on this website, it was long considered an ancient piece, but starting with Winckelmann in 1756 was rightly identified as modern, owing to its strong correspondences with the work of Michelangelo.

In the (slender) modern scholarship on this statue, no one has doubted that it is a work of the 16th century. But can it really be by the hand of Michelangelo itself? One massive objection to the attribution was recently voiced succinctly by Victor Coonin: it enters the 17th century Ludovisi collection seemingly out of nowhere. “That everybody would’ve ignored it or didn’t know about it”, explains Coonin, “that Michelangelo wouldn’t have mentioned it to anyone, that nobody mentioned it as being a Michelangelo within Michelangelo’s lifetime — I think that that’s rather unlikely for such a large and idiosyncratic sculpture to escape complete mention in the literature.”

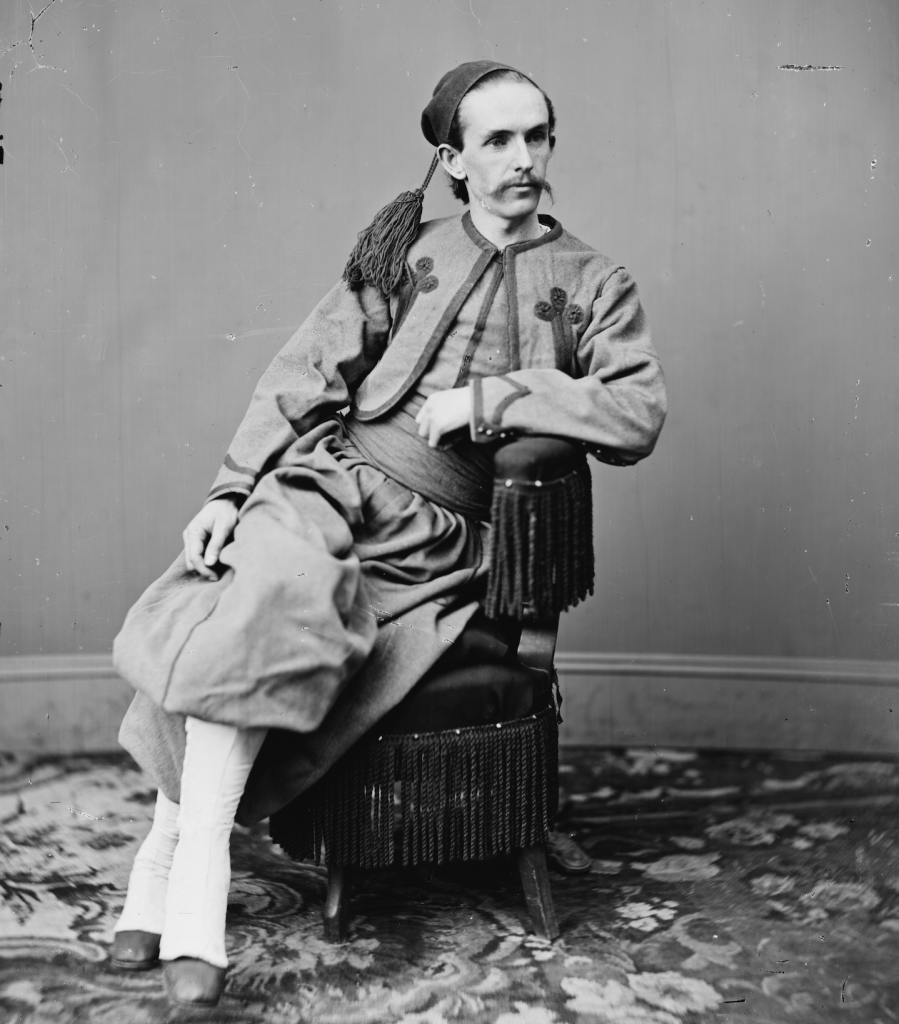

Detail of frescoes in the Aula di Adone, Rocca dei Rossi, San Secondo Parmense: portrait (presumed) of Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi. Credit: R. Pagani / flickr

However, if its provenance was the collection of Bishop Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi, specifically the part he buried for safekeeping on the Pincio on land that Cardinal Ludovisi subsequently developed, that would explain how this large sculpture could go missing for much of the 16th and early 17th century, and be mistaken as an ancient sculpture when finally excavated.

As we have seen, the figure of de’ Rossi provides a straight line from Michelangelo to the Orsini portion of the future Villa Ludovisi. Cardinal Raffaele Riario, who gave Michelangelo his first major commission in Rome, was the bishop’s relative and energetic patron. De’ Rossi himself was also related to the Medici, spent much of his adult life in either Rome or Florence, and lavished praise on Michelangelo (as well as Vittoria Colonna) in his poetry.

What is more, Bishop de’ Rossi clearly was interested in woodland deities: as we have seen, an (incomplete) inventory of his collection of sculptures shows figures of both a male and female satyr, as well as a Silenus. He also invokes “the god Pan” in his verse. Put simply, if Michelangelo or a contemporary follower had created the Ludovisi Pan, there is no practical objection to it featuring in de’ Rossi’s collection.

As Hatice Köroglu Çam has shown at length on this website, the Ludovisi Pan shows close correspondences to a number of Michelangelo’s works in different media. Of sculptures, it is perhaps the “Bacchus” (1497)—purchased by Cardinal Raffaele Riario—that offers the closest parallels.

Detail of frescoes in the Aula di Adone, Rocca dei Rossi, San Secondo Parmense: portrait of Cardinal Raffaele Riario. Credit: R. Pagani / flickr

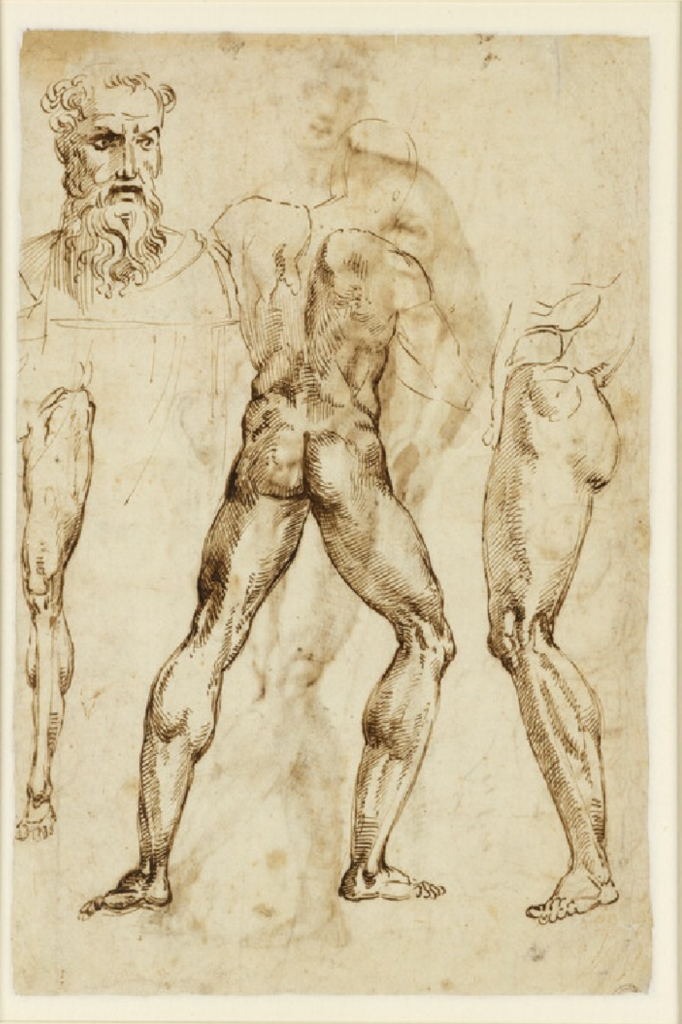

What follows is a review of what we know about Riario’s commission of that work, and what Michelangelo’s biographer Ascanio Condivi has to say about the relationship between artist and patron.

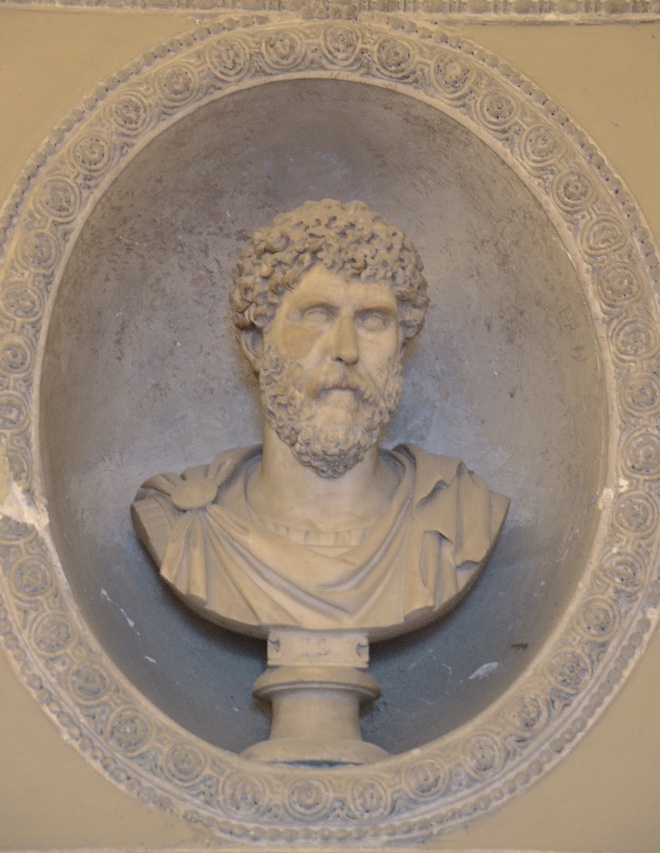

Michelangelo Buonarroti made his first visit to Rome on 25 June 1496 upon the invitation of Cardinal Raffaelle Riario, cardinal deacon of S Giorgio in Velabro. Michelangelo stayed in the city until 1501. As recounted in 1553 by his authorized biographer, Ascanio Condivi, he spent a year under the patronage of Cardinal Riario, while also enjoying the support of Jacopo Galli and Cardinal Jean Bilheres de Lagraulas. Cardinal Riario, renowned for his collection of antiquities and his patronage of the arts, was Michelangelo’s first patron in Rome.

Medal (unsigned) with obverse portrait of Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici (1463-1503). The reverse depicts a bear with cub. Credit: Leipziger Münzhandlung und Auktion Heidrun Höhn.

In his first letter (2 July 1496) to Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici, who belonged to the younger branch of the powerful Florentine family, Michelangelo explicitly reveals that Cardinal Riario had commissioned him to carve a statue of Bacchus. He provides intricate details, specifically mentioning the acquisition of marble, presumably for the “Bacchus”, a notable achievement, marking “the first large-scale marble sculpture of Bacchus since antiquity”, as noted by H. O’Leary McStay. In this letter, Michelangelo recounts Cardinal Riario’s warm reception, detailing his introduction to the cardinal’s esteemed antique collections housed within the Cancelleria Palace. Here Michelangelo subtly hints at the “Bacchus” commission, stating, “we have bought a piece of marble for a life-sized figure and on Monday I shall begin work” (Ramsden, Letters p3). The letter to Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici is worth quoting in full:

“This is only to let you know that we arrived safely last Saturday and at once went to call upon the Cardinal di San Giorgio [i.e., Riario], to whom I presented your letter. He seemed pleased to see me and immediately desired me to go and look at certain figures; this took me all day, so I could not deliver your other letters that day. Then on Sunday, having gone to his new house, the Cardinal sent for me. I waited upon him, and he asked me what I thought of the things I had seen. In reply to this I told him what I thought; and I certainly think he has many beautiful things. Then the Cardinal asked me whether I had courage enough to attempt some work of art of my own. I replied that I could not do anything as fine, but that he should see what I could do. We have bought a piece of marble for a life-sized figure and on Monday I shall begin work.”

“Then last Monday I presented your other letters to Pagolo Rucellai, who placed the money at my disposal, and to the Cavalcanti likewise. Then I gave Baldassare his letter and asked him for the cupid, saying that I would return the money. He replied very sharply that he would sooner smash it into a hundred pieces; that he had bought the cupid and it was his; that he had letters showing that the buyer was satisfied and that he had no expectation of having it to return. He complained bitterly about you, saying that you had maligned him. Some of our Florentines sought to arrange matters between us, but they effected nothing. Now I count upon acting through the Cardinal, for thus I am advised by Baldassare Balducci. You shall be informed as to what ensues. That’s all this time. I commend me to you. May God keep you from harm.” MICHELANGELO IN ROME.

Nevertheless, Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo’s pupil and official biographer, implicitly dismisses the notion of the commission by Cardinal Riario, while also critiquing the cardinal’s taste and knowledge of art. Both Condivi and Vasari assert that it was Jacopo Galli, a rich banker and collector, who was the patron who commissioned “Bacchus”. Scholars concur that Michelangelo—as Condivi mentions—sculpted his “Bacchus” at Jacopo Galli’s house in Rome. Indeed E. Sutherland Minter highlights the earliest description of Bacchus—at Galli’s house in 1506.

All this raises a question: why did Michelangelo come to Rome at that time and meet with Cardinal Riario? As it happens, this July 1496 letter of Michelangelo unveils the true genesis of the story. The answer lies with his “Sleeping Cupid” referenced in the letter. Both Condivi and Vasari recount the well-known tale of this life-size sculpture—”a god of love, aged six or seven years old and asleep”, as Condivi describes it—which Michelangelo had carved in Florence the previous year, in 1495, aged just 20.

Drawing of a cupid (Windsor Castle inv. 8914), possibly depicting the (lost) Sleeping Cupid of Michelangelo. Credit: Paul F. Norton, The Art Bulletin 39 (1957).

According to Vasari, the tale unfolds as follows. Baldassare del Milanese showed the Cupid to Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici as a splendid piece of craftsmanship. Lorenzo then advised Michelangelo, “If you were to bury it, I am certain it would pass as an ancient work. If you were to send it to Rome treated to appear old, you would earn much more than by selling it here.” Vasari elaborates this story, “the artist manipulated the stone to give it an aged appearance. Subsequently, Baldassare del Milanese buried it in a vineyard near Rome and sold it as an antique to Cardinal Raffaele Riario for 200 ducats.”

Upon realizing that he had acquired a “counterfeit antiquity,” Riario returned the sculpture and received a full refund. Vasari remarks that Cardinal Riario “failed to recognize the value of this sculpture.” When Michelangelo learned of the incident, Baldassare had already made a significant profit, and despite Michelangelo’s demands, the dealer refused to return the artwork. The second part of Michelangelo’s 2 July 1496 letter recounts this narrative. While Condivi concludes that “no one suffered more from this ordeal than Michelangelo,” Vasari suggests that this event elevated Michelangelo’s reputation to such an extent that he was promptly invited to Rome and received into the household of Cardinal San Giorgio (i.e., Cardinal Riario), where he resided for almost a year.

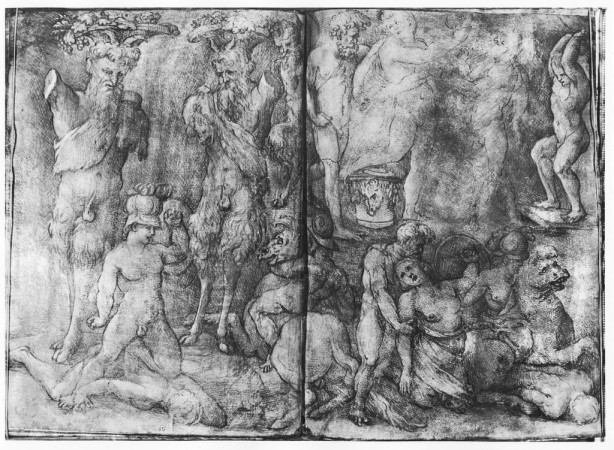

Maarten van Heemskerck (ca. 1532-1536), Garden of the Casa Galli. Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Kupferstichkabinett, Inv. 79 D 2, fol. 72 recto. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

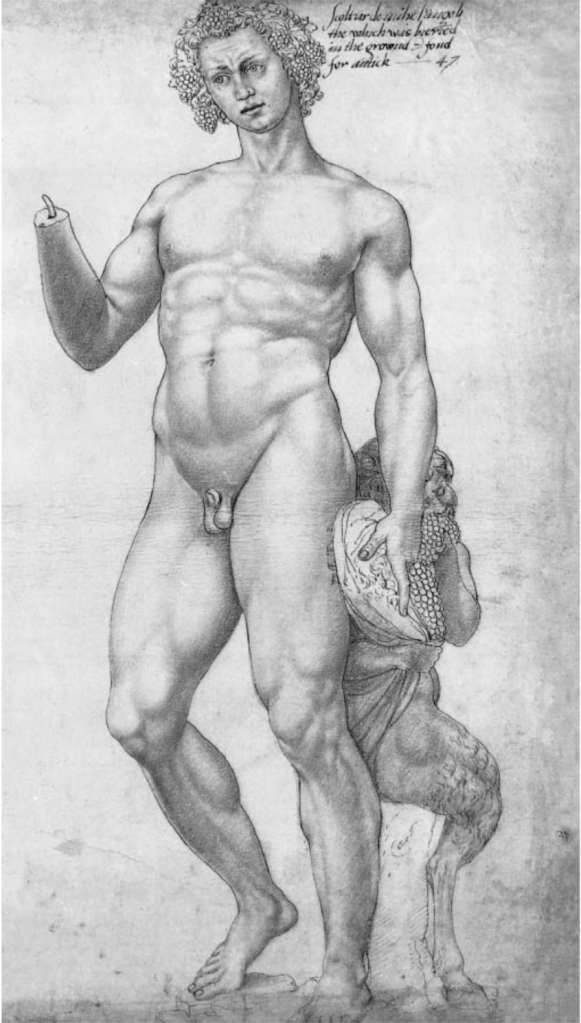

E. Wind confirms Riario’s admiration for Michelangelo’s talent, noting that the style of the Liberalitas on Riario’s medal reflects his pseudo-antique taste. Wind also discusses Maarten van Heemskerck‘s drawing (ca. 1532-1536) of the sculpture garden of Jacopo Galli. There the “Bacchus” is depicted with a broken hand, suggesting that “in the drawing, the statue was perceived as pseudo-antique.” The drawing reveals that the right hand of Michelangelo’s statue was broken off below the wrist—possibly to be restored with the original hand holding an all’antica wine bowl—while the penis remains chiseled away. The collection of Trinity College Cambridge offers another Renaissance-era depiction of the “Bacchus”. Significantly, the inscription on the Cambridge drawing reads: “Scoltur de Michelangeli the which was buried in the grownd and fond for antick”. McStay suggests that the breakage of the hand “was done on purpose to enhance the appearance of antiquity.”

Drawing after Michelangelo’s “Bacchus”, Cambridge sketchbook, fol. 14. Cambridge: Trinity College Library. Credit: Linda A. Koch, Art History 29 (2006).

Both Condivi and Vasari connect this narrative of “Sleeping Cupid” to the “Bacchus” commission. However each rejects the notion that Riario was the commissioning patron, and instead attribute agency to Jacopo Galli. Both these biographers assert that Cardinal San Giorgio (Cardinal Riario) had little comprehension of the arts and did not engage Michelangelo in any significant tasks. Condivi, in particular, is eager to emphasize that “Michelangelo was never officially commissioned by San Giorgio (Cardinal Riario) to undertake any work.”

If we agree with Condivi’s and Vasari’s assertion, we have to believe that Jacopo Galli commissioned the “Bacchus”. However, Wind specifically highlights Condivi’s unreliability regarding such descriptions despite the fact that he wrote under Michelangelo’s direct supervision, suggesting that “it is difficult to trust Condivi on any detail”. It is crucial to remember, as Minter points out, that neither Condivi nor Vasari were even born at the time when “Bacchus” was carved. Moreover, both Cardinal Riario and Galli were dead by the time Condivi wrote his Vita.

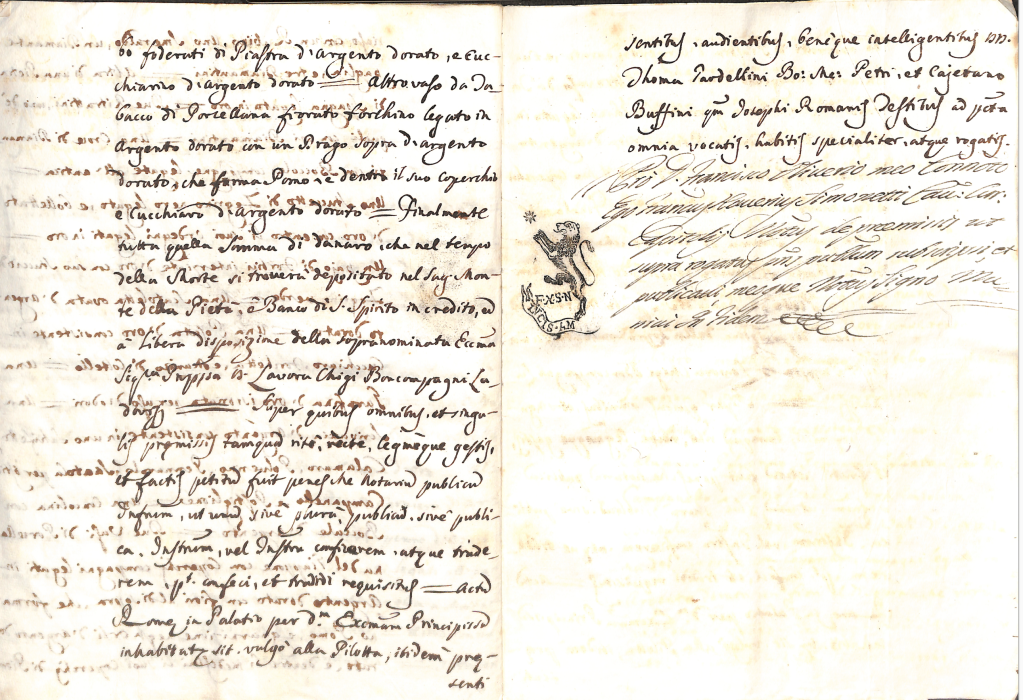

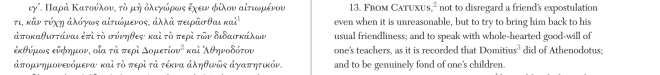

Item from accounts (1496-1497) of Baldassare Balducci, showing payment by Cardinal Riario to Michelangelo for the Bacchus. Credit: M. Hirst, The Burlington Magazine 123 (1981).

Minter further underscores a decisive point, for which we have documentary evidence: that Michelangelo received full payment for “Bacchus” from Cardinal Riario. McStay explains how the patronage worked, stating that, though it was Cardinal Riario who provided financial support and sponsorship of the artist’s work, Michelangelo carved his “Bacchus” at Galli’s residence. Minter notes that “on September 19th, 1496, Riario sent two barrels of wine to Michelangelo at Jacopo Galli’s house.”

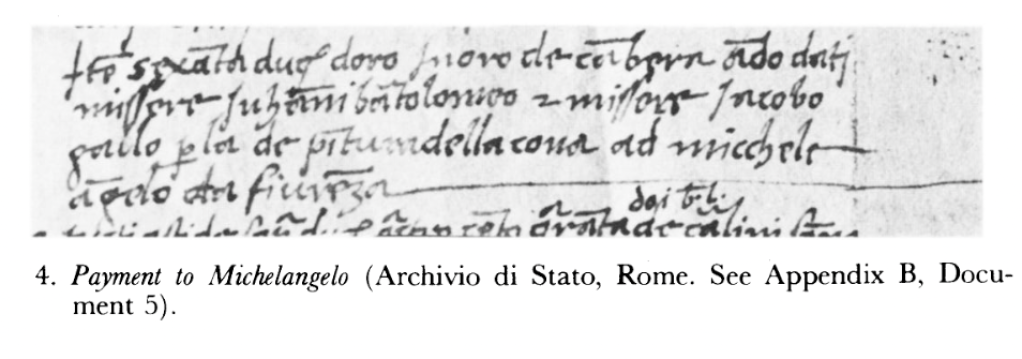

It was M. Hirst who in 1981 provided conclusive details about Michelangelo’s commission, drawing on entries in the account books of Baldassare Balducci. Hirst shows that the Libro di Creditori e Debitori 1496-98, Balducci Libro no. 2, confirms Riario’s patronage and specifies the execution date of the “Bacchus”, namely the summer of 1496 into the summer of 1497. This account records three payments, all from Riario’s funds, with one specifically designated for the “Bacchus” commission.

Indeed, Vasari’s account of Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de’ Medici’s suggestion to Michelangelo to bury a modern statue to create an antique impression adds an intriguing dimension to this study, namely using inhumation in the creation of pseudo-antiques. H. Bredekamp highlights both Michelangelo’s “Sleeping Cupid”, which is said to have conveyed an antique impression thanks to this method, and the (intentionally) damaged state of “Bacchus”‘s hand and penis. Bredekamp also mentions some reports suggesting that Michelangelo not only intentionally mutilated this figure but even buried it with the intention of later unearthing it as an authentic antique. The annotated Cambridge sketch of the “Bacchus” of course reflects that tradition.

This brings us to another essential problem to highlight: the creation of sculptures of pagan deities such as the “Bacchus” within the deeply Christian atmosphere of the late 15th and 16th centuries. L. Freedman underscores that “cardinals of the church typically did not commission statues of pagan gods and goddesses; instead, they tended to collect genuine antiquities”. However, “when authentic antique statues were unavailable on the market”, Freedman says, “it is likely that copies or replicas would have been commissioned”. Cardinal Riario’s rejection of “Bacchus” but his full payment for its execution implies his dilemma about commissioning a pagan deity in such a climate.

As one can imagine, the issue would have been particularly acute in the case of the Ludovisi Pan, an indubitably late fifteenth or sixteenth century sculpture that represents the Greek woodland god with an erect phallus. Who in the sphere of contemporary Papal Rome would dare to commission such a pagan statue with such a provocative feature and display it prominently in one’s garden?

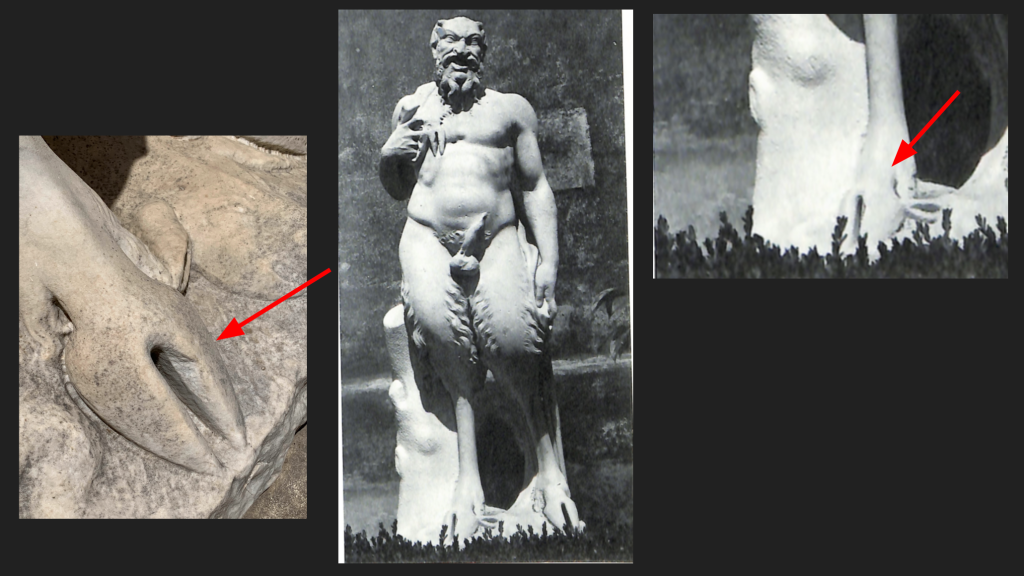

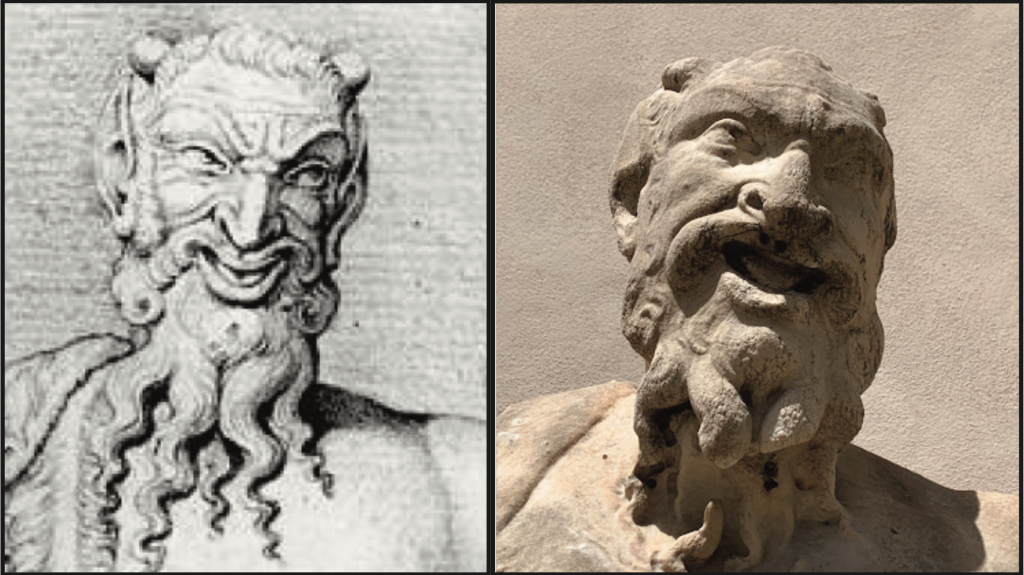

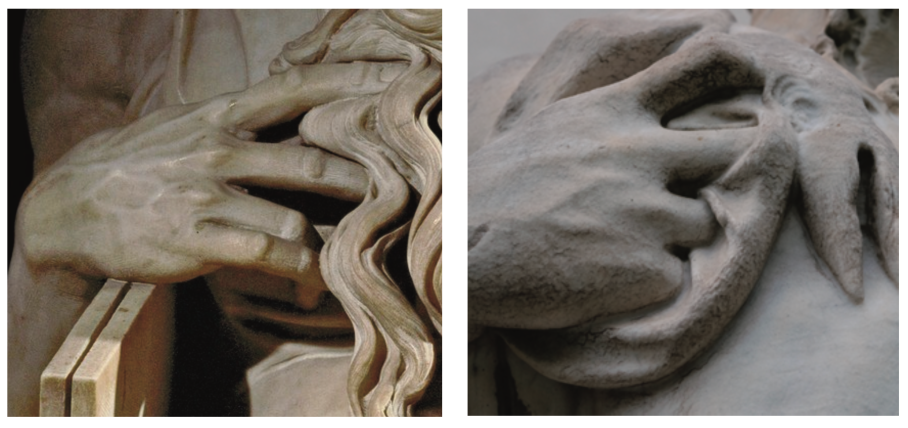

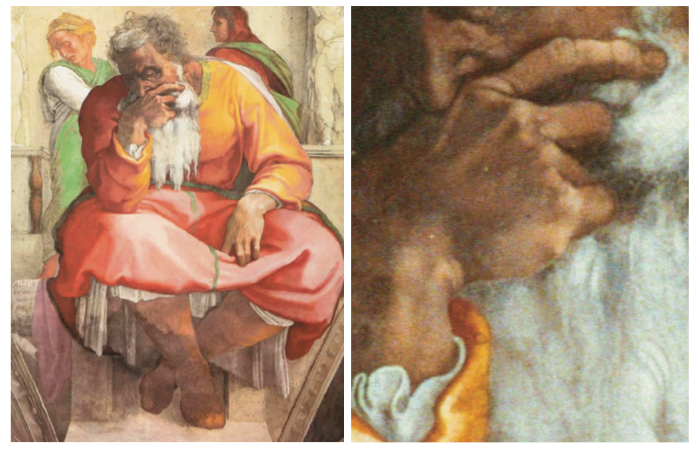

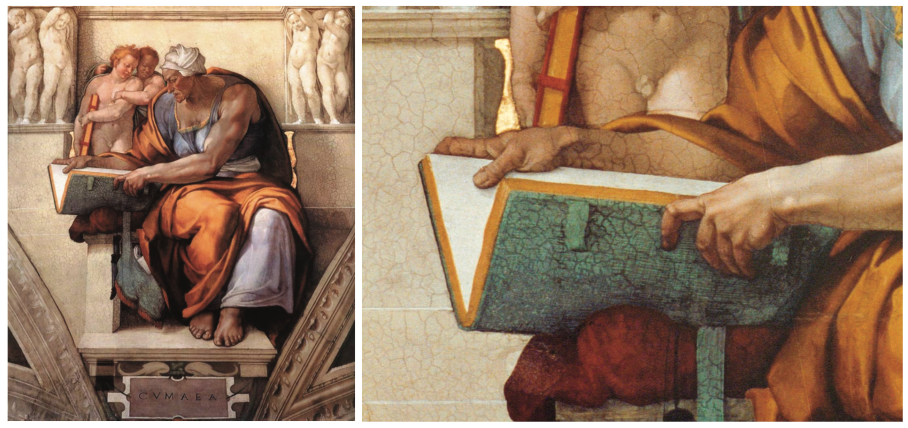

Comparison of details of Michelangelo, Bacchus (1496-7), Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (via Wikimedia Commons), at left, with Ludovisi Pan (credit: TC Brennan), at right.

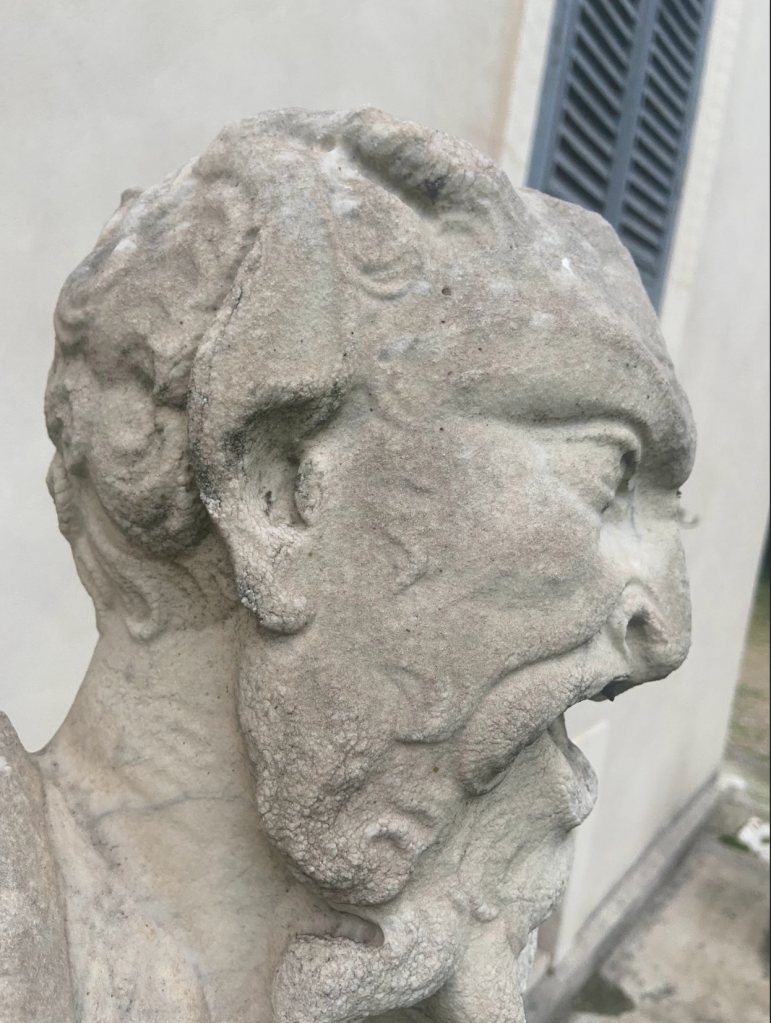

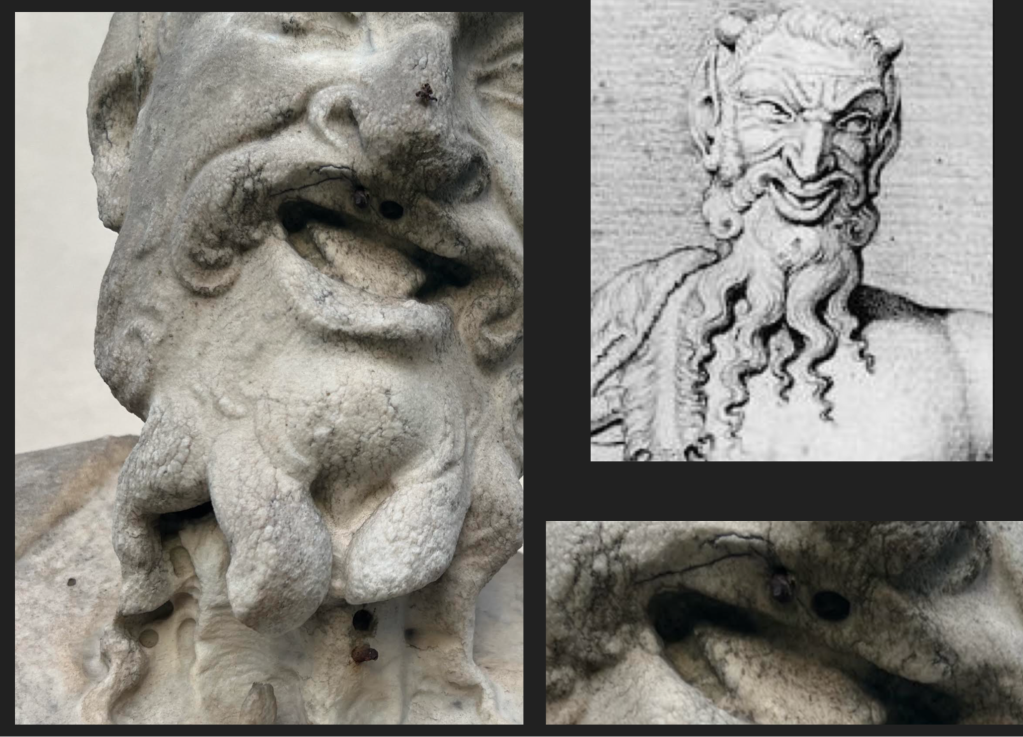

As Hatice Köroglu Çam has shown in detail on this website, there are strong stylistic similarities between the Ludovisi Pan and Michelangelo’s “Bacchus”. Consider the left hand of the Pan and the primary motifs of the left hand of “Bacchus”. It can be seen that they show nearly identical gestures—except that the index finger is not curved in the case of Pan. Both figures also hold animal pelts, a motif derived from Greek and Roman art. There is also a general resemblance between the Pan and the satyr figure in the “Bacchus” group: notably, the pointed ears, the carving of animal heads leaning against the left legs of both the satyr and Pan, and the rendering of their hoofs. Moreover, the curled beard and hair of the Ludovisi Pan bear a striking resemblance to the depiction of the individual twisted curls of hair on the head of the satyr in Michelangelo’s “Bacchus” group. These curls are depicted independently as a distinct stylistic component of the hair.

Comparison of details of Michelangelo, Bacchus (1496-7), Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (via Wikimedia Commons), at left, with Ludovisi Pan (credit: TC Brennan), at right.

As it happens, the “Bacchus” and the Pan also show parallels in the fate of their reception as Pagan gods. Bacchus’s portrayal, reflecting his excessive indulgence in wine, demonstrates Michelangelo’s profound engagement with the character of the figure—indeed its very essence. Freedman goes further, and describes how “Bacchus is portrayed as being aware of the potential dangerous effects of wine”. Yet the “Bacchus” has faced criticism, as Liberman notes, for his “awkward pose, vulgar facial expression, and softly effeminate pose”.

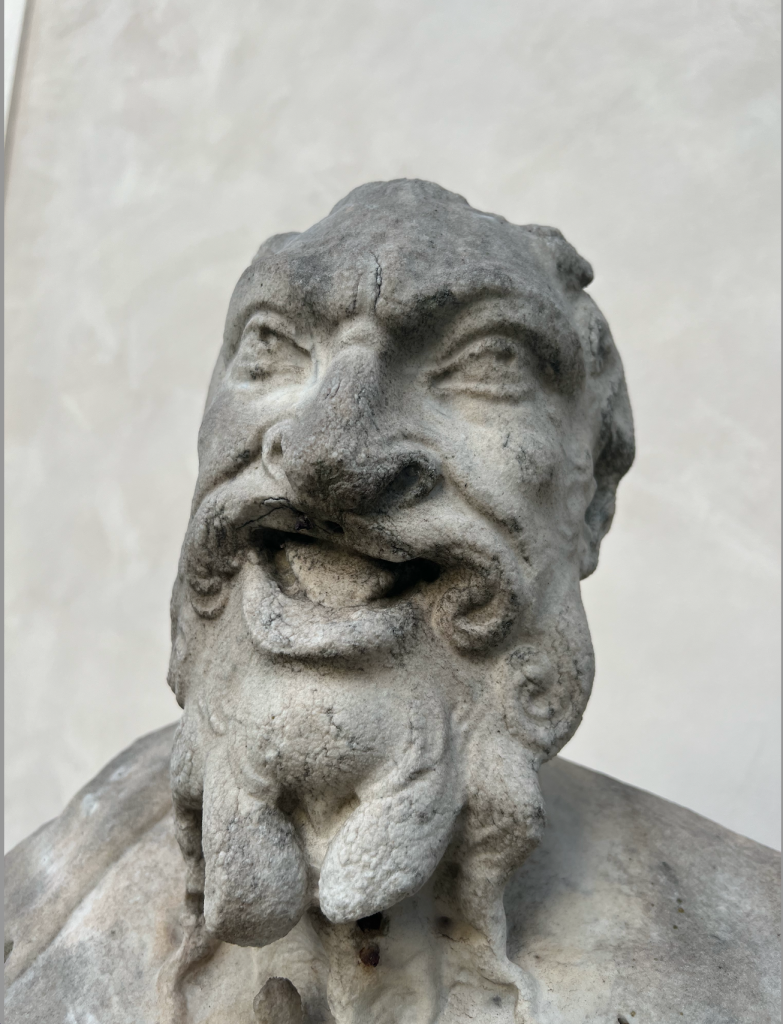

Similarly, the Pan, has often been disparaged, especially since the 1850s, for his perceived ugliness—even described as “a little bit lifeless” by Victor Coonin. But it is difficult to see how, if Michelangelo had created a statue of the Greek god, he could have avoided depicting an ugly figure with pointed ears, horns, and an erect phallus, accompanied by a laughing mouth. That depiction is consistent with the mythological and artistic conventions surrounding Pan’s portrayal. The expression conveyed by Pan shares a similar motivation to that of the “Bacchus”. Pan’s face, coupled with a laughing mouth, vividly portrays his mischievous and lustful nature, but also a sense of awareness reflecting his unpredictable nature.

Comparison of details of Michelangelo, Bacchus (1496-7), Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (via Wikimedia Commons), at left, with Ludovisi Pan (credit: TC Brennan), at right.

Put simply, the two sculptures show a number of strong similarities, so many that we must consider the possibility that Michelangelo created both sculptures, perhaps even in close proximity to each other. The numerous points of comparison underscore the sculptor’s ability to convey the essence and mood associated with each figure through their physical attributes, facial expressions, gesture, and accoutrements. Each piece highlights the sculptor’s skill in bringing characters to life and capturing their distinctive personalities and traits in his art.

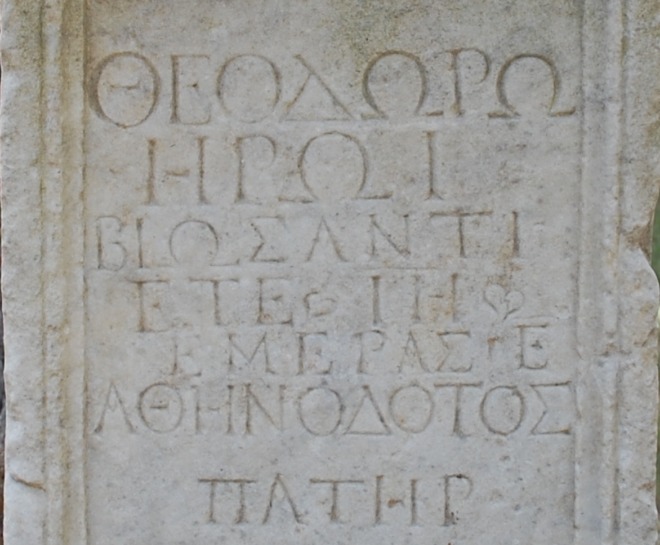

Let us sum up the focus of our investigations here. The “Bacchus” group that Cardinal Raffaele Riario commissioned Michelangelo to create in 1496 shows many striking points of contact with the Pan, a piece that is found in the earliest stratum of the Ludovisi collection of sculptures. There is also a direct line that connects Cardinal Riario with Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, namely Riario’s relative and protegée Bishop Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi, who in the mid-sixteenth century is known to have buried part of his large collection of sculptures on his Pincio vigna, land that later passed to the Orsini and then the Ludovisi. Furthermore, when we recall testimonies regarding the Pan from the 17th and 18th century such as those of Pietro Sebastiani (1683)—indeed all who discuss the work before Winckelmann in 1756—it is clear that the statue was universally regarded as ancient in date.

Our hypothesis? The Pan statue, whose face resembles that of Michelangelo himself, is either by the master or at the very least by one of his contemporaries seeking to emulate his style closely. The fact that the statue escapes all notice in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century suggests the possibility that this statue was deliberately buried by someone—one suspects immediately the factious Bishop de’ Rossi—and later unearthed by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi on ex-de’ Rossi property. The motive for burying? Safekeeping comes most immediately to mind, especially given Bishop de’ Rossi’s tumultuous career. Alternatively, one also remembers the story of Michelangelo burying the “Sleeping Cupid” and the similar rumors (discussed by Bredekamp) concerning his “Bacchus” group, where Michelangelo’s creations are in on or both cases passed off as authentic antiques.

It is possible a similar situation may have obtained here with the Pan. Indeed, as we have seen, L. Freedman has suggested that with the “Bacchus”, Michelangelo aimed to create a statue that could immediately deceive spectators into believing it to be authentically antique. Whatever the precise case, the hypothesis that the Pan was long buried, on land that passed from Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi to the Orsini and then to the Ludovisi, may help us comprehend the origins of the Ludovisi Pan, and its reception as an ancient statue well into the 18th century, when on the basis of connoisseurship a consensus formed that it was by the hand of Michelangelo.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barocchi, P. and G. Gaeta Bertelà. 1993. Collezionismo mediceo: Cosimo I, Francesco I e il Cardinale Ferdinando. Documenti (1540-1587). Modena: Franco Cosimo Panini Editore.

Boyer, F. 1933. “Nouveaux documents sur ls antiques Médicis (1560-1583)”. Études Italiennes 3: 5-16.

Bramanti, V. 1995. Giovangirolamo de’ Rossi: Vita di Federico Montefeltro. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore.

Bull, G. and P. Porter. 2009. Michelangelo, life, letters, and poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bredekamp, H. 2021. Michelangelo. Berlin: Verlag Klaus Wagenbach.

Freedman, L. 2003. “Michelangelo’s Reflections on Bacchus.” Artibus et Historiae 24: 121–35.

Hirst, M. 1981. “Michelangelo in Rome: An Altar-Piece and the ‘Bacchus.’” The Burlington Magazine 123: 581–93.

Lieberman, R. 2001. “Regarding Michelangelo’s ‘Bacchus.’” Artibus et Historiae 22: 65–74.

McStay, H. O’Leary. 2014. ‘Viva Bacco e viva Amore’: Bacchic Imagery in the Renaissance. Diss. Columbia University.

Minter, E. S. 2014. “Discarded Deity: The Rejection of Michelangelo’s ‘Bacchus’ and the Artist’s Response.” Renaissance Studies 28: 443–58.

Ramsden, E.H. 1963. The Letters of Michelangelo. Vol. 1. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Wind, Edgar. 1995. “A Bacchic Mystery by Michelangelo”. In Michelangelo: Selected Scholarship in English, ed. William E. Wallace. New York & London: Garland.

Hatice Köroglu Çam (she/her) is currently pursuing her PhD in Italian Renaissance art at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and Architecture. She graduated with honors, achieving summa cum laude, from Rutgers University in 2022 with a B.A. in Art History. During the spring and summer of 2022, Hatice completed an internship at the Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi project. Over the past two years, Hatice has delved deeply into her research on a 16th-century statue of Pan located in the gardens of the Casino dell’Aurora in Rome. Under the guidance of Professor T. Corey Brennan from the Rutgers Classics Department, her exploration has led to significant scholarly contributions, culminating in a comprehensive four-part article titled “A New Self-Portrait of Michelangelo? The Statue of Pan at the Casino dell’Aurora in Rome.” Hatice has presented her findings at the ‘Pan and the Anthropocene’ symposium hosted by Bristol University on 20 July 2023, and at the Classical Association of Atlantic States annual meeting on 6 October 2023. She expresses profound gratitude to Professor Brennan for introducing her to this unstudied work of art and for offering invaluable contributions, interpretations, guidance, and support throughout the research process. Hatice expresses her gratitude to HSH Princess Rita Boncompagni Ludovisi for her unwavering support, encouragement, and dedication to preserving the statue, which served as a significant inspiration throughout her research journey. Her invaluable support has played a pivotal role in the success of this study.

The Ludovisi Pan at the Casino dell’Aurora, October 2022. Credit: TC Brennan.