Mary Wollstonecraft was born the 27th of April 1759 likely in London, England. Raised in a middle-class family that ran into financial troubles later on, she decided to create a career for herself as an author after the moderate success of her first novel, Mary: A Fiction (1788). During the French Revolution, Wollstonecraft wrote Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) in response to Edmund Burke’s conservative critique of the revolution, and also went to France to participate in the revolution. Soon after she released her most well-known text A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Within Rights of Woman Wollstonecraft uses logic and philosophies that would be considered very restrictive and misogynistic by today’s standards, even though she is considered one of the earliest feminists. One could argue that Wollstonecraft used these as rhetoric, but one could also argue that they are true to her actual beliefs. Since there is a lot of existing research into Wollstonecraft, I will be exploring this question more in depth by investigating her writings and personal life.

In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman Wollstonecraft states that women are not inherently inferior to men, and that they only appear so because they have been denied a proper education, leaving them ignorant. Hence, she advocates for the education of women, specifically coeducation with men. To begin with, Wollstonecraft critiques conduct books, a genre of books educating on social norms, as she is critiquing the status quo social state of women. She refers to the purpose of conduct books as being “to degrade one half of the human species and render women pleasing at the expense of every solid virtue”[1], and as a large proponent of equality she upholds the idea that marriage should be a companionship between two equal parties and not that of a mistress and a man.

In addition, she not only argues that the lack of education of women is at the expense of their virtue, but that coeducation will also improve the virtue of men. Wollstonecraft claims that “at school boys become gluttons and slovens”[2] as the juniors are up to mischief and seniors up to vice. The culture at schools do not teach boys modesty and they lose that “decent bashfulness”[3] which they might have learned at home. Wollstonecraft also elaborates on the “bad habits which females acquire when they are shut up together”3, such as learning vanity. Hence, Wollstonecraft proposes a national public education plan based in giving boys and girls the same education in the same environment to fix these vices that arise in sexually segregated schools. Another benefit of the education plan that Wollstonecraft outlines include making women better mothers. Surprisingly, Wollstonecraft argues for her education plan by stating that that any weakness of the mother will be imparted on the children, and they can learn basic anatomy and medicine to better care for children[4].

Mary Wollstonecraft portrait 1791. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

Now you may be asking yourself “hmm, why would a feminist writer be concerned with making women better mothers”, just as I was while reading Rights of Woman. A popular theory as to why Wollstonecraft frames her arguments in an almost anti-feminist way is that Wollstonecraft is using them as a rhetorical strategy to cloak her more radical ideas granting them passage into public discourse. An alternative interpretation is that Wollstonecraft is a product of her times, and her conservative beliefs are a part of her philosophy. However, as I am going to explore, Wollstonecraft is not afraid of challenging social norms expected of women and has a radical background.

The basis for Wollstonecraft’s argument for equality between men and women is intellectual, but also political and financial, as she argues that women should be included in the political sphere and should be able to financially support themselves. In addition, she has lots of dialogue about marriage being a partnership. In conjunction, she implies that men and women should share equal roles and responsibilities in a marriage, which should also extend to raising children. In other words, she believes women should be interested in fatherhood (and fathers in motherhood). Thus, we can suggest that Wollstonecraft would have wanted equal responsibility between parents in raising children. This would challenge the social norms of her time, suggesting underlying radical rather than conservative theories. There are plenty more texts to analyze before we come to a solid conclusion. Maybe it is time to call in some reinforcements to help answer this question.

Paul E. Kerry, a professor of history at Brigham Young University focusing on research of eighteenth and nineteenth century interdisciplinary European and transatlantic political and historical thought, writes that Wollstonecraft’s conservative writings about gender – which perplex feminist theorists – are “essential to her argument … the root of her philosophical thinking”[5]. Kerry claims that the arguments are too “tirelessly omnipresent” to simply be just a cloak granting passage of her thoughts into public discourse. Which is compelling considering how frequent Wollstonecraft’s use of these arguments are. Kerry argues that Wollstonecraft equates being a good mother with being a good citizen[6] and that Wollstonecraft argues for a sexual puritan ethic. Within Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft herself heavily and blatantly critiques prostitution and lust. Kerry ultimately claims that these views are integral to Wollstonecraft’s philosophy, not as a rhetorical strategy but true to her own beliefs. This must then be a point to Wollstonecraft’s conservatism then.

I must push back: arguing that wanting to not be objectified and being a mere vessel for self-gratification is not sexual puritanism and perfectly self-consistent with Wollstonecraft’s overarching argument of equality between the sexes. While Wollstonecraft does not explicitly say that this equality ought to be extended into all aspects of society, including sexually, she surely implies it can be. Looking at Wollstonecraft’s argument, including the part Kerry summarizes, Wollstonecraft characterizes prostitution as being the objectification of women and only providing gratification to men. Thus, we see that Wollstonecraft is still arguing for equal treatment and social standards between the sexes and she is pointing to the reasons they are needed, not arguing for sexual puritanism. Well, this answered the question about why Wollstonecraft may be perceived as a sexual puritan, but this cannot be extended to why she was so concerned with motherhood. For me, the text is not explicit as to why Wollstonecraft is concerned with making good mothers. I think we should look outwards towards her personal life for some clarity.

Despite the omnipresence of conservatism in her writings, there is an obvious connection between Wollstonecraft’s writings and the global political movements at the time, specifically revolutionary ones. From 1765 to 1791 the American Revolution was ongoing, which inspired the French Revolution from 1789 to 1799. A common philosophy present in both revolutions are the inherent rights of people, evident from the U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789). Wollstonecraft is clearly interested by the philosophies discussed within these movements as she went to France with the intention to participate in their revolution. During this time period, however, revolutionaries did not write in the general sense of humanity but rather wrote from the point of view of men, excluding women. In A Vindication of the Right of Women Wollstonecraft tackles this issue and argues for equality between the sexes, with clear revolutionary influences.

In addition, Wollstonecraft’s personal life suggests she is sex positive, and she does not degrade prostitutes for the work they do, but rather critiques the institution of sex work. Wollstonecraft explicitly states that women are sexual beings and that extramarital affairs should be used for pleasure. Wollstonecraft and her husband, early anarchist William Godwin, were large proponents of free love and renounced the institution of marriage[7].

Wollstonecraft might have hidden her radical ideas on sex because of the scorn of public opinion, but she was still attacked when her affairs later became public. Wollstonecraft lived an unorthodox lifestyle which became public when Godwin published a posthumous memoir, Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798). This memoir revealed Wollstonecraft’s premarital affair with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay which resulted in a child. The memoir also revealed Wollstonecraft’s subsequent suicide attempts. These events in Wollstonecraft’s life were considered shameful resulting in a public renouncement of her work and ruined her reputation to the extent that her name was equated with the dangers of radical feminism. We can see that if Wollstonecraft were to include her unfiltered personal beliefs in Rights of Woman, that the text would have been immediately rejected and suppressed. From the second the text entered the hands of readers Wollstonecraft would have encountered opposition.

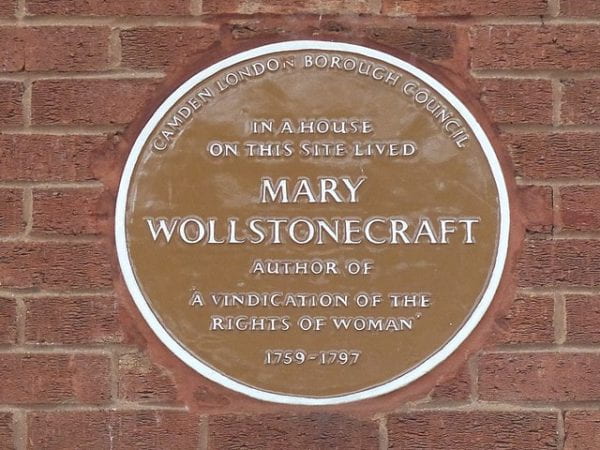

Mary Wollstonecraft plaque in London. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

We can investigate how Rights of Woman was actually received positively in spite of her radical lifestyle. Regina Janes, a scholar of eighteenth-century English literature, illuminates how Rights of Woman was received when it was published. Janes analyzes the reviews Rights of Woman received at the time of its release and points out that the reviews were all positive[8]. Wollstonecraft had already gained some popularity and name recognition from her work on A Vindication of the Rights of Men and the Analytical Review. All periodicals that positively reviewed Rights of Men gave Rights of Woman a positive review, except for one, which did not give a review at all. Janes claims that is the general sentiment of how the Rights of Woman was received, with favorable reviews and ignored by most who would oppose the political assumptions Wollstonecraft held. The reason so many ignored the text was because Rights of Woman was not received as a political text, but mainly “a sensible treatise on female education”[9]. The only negative review that Jane was able to uncover was from the Critical Review which only argued to “maintain the essential inferiority and necessary subordination of women”[10]. The Critical Review had no issue with the education of women but disagreed with Wollstonecraft’s intellectual equality between the sexes, which Janes points out is just male contempt for feminine duties. Janes is essentially arguing that the reason Rights of Woman was not negatively received is because most people did not perceive Rights of Women as a political text. It wasn’t until Godwin published Wollstonecraft’s extremely controversial memoirs that Rights of Woman was perceived as a radical text[11]. In other words, Wollstonecraft’s rhetoric was moderate in contrast to her lifestyle, and thus we can conclude that Wollstonecraft’s conservative rhetoric was both necessary and successful for the publication of her work.

If Wollstonecraft were to argue for more radical ideas, like “equal access to professions, equal treatment under the law and abolition of discrimination on the basis of sex”, which are consistent with the arguments made in Rights of Woman, readers would have found Rights of Woman more disagreeable and possibly vile. Janes concludes that Wollstonecraft uses moderate rhetoric to provide “a variety of specific recommendations … firmly in the forefront of eighteenth-century education discussion”[12]. I would further conclude that Wollstonecraft shielded her argument behind rhetoric that would appeal to readers during her time, like making women better mothers and wives.

I believe that the juxtaposition between the positive reviews of the Rights of Woman and the subsequent villainization of Wollstonecraft after Godwin’s publication of her memoir demonstrate that Wollstonecraft was using motherhood and other traditional feminine ideals as a rhetorical strategy to shield her radical ideas of equality. Instead of seeking radical changes, Wollstonecraft sought to make piecemeal improvements like better education for women. She lived a very radical lifestyle that was defiant of gender norms at that time. If she had not used these rhetorical strategies Rights of Woman would have been received negatively and not sparked any public discourse, essentially making moot her goals for the text.

A Vindication of the Rights of Women is one of the earliest feminist texts, making Wollstonecraft one of the first feminists. Whether or not we believe Wollstonecraft held the more conservative ideas present in her writings, Wollstonecraft was still one of very few writers on the political rights of women at the time, making her an extremely progressive writer. Wollstonecraft’s careful rhetoric allowed her to lay the foundations of feminism, which subsequent generations were able to build upon and realize even her most radical ideas.

About the Author:

Ethan Croitoru is an undergraduate student at the University of Chicago studying computational and applied math as a part of the class of 2022. Originally from Chicago, Il, Ethan plans to pursue a career in data science.

References:

Featured Image: Mary Wollstonecraft. Source: Foundation for Economic Education 2016.

[1] Wollstonecraft, Mary. “A Vindication Fo the Rights of Woman.” A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and A Vindication of the Rights of Men, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 87

[2] Wollstonecraft, Mary. “A Vindication Fo the Rights of Woman.” A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and A Vindication of the Rights of Men, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 242

[3] Wollstonecraft, Mary. “A Vindication Fo the Rights of Woman.” A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and A Vindication of the Rights of Men, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 249

[4] Wollstonecraft, Mary. “A Vindication Fo the Rights of Woman.” A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and A Vindication of the Rights of Men, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 263

[5] Kerry, Paul E. “Mary Wollstonecraft on Reason, Marriage, Family Life, and the Development of Virtue in a Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” BYU Journal of Public Law, vol. 30, no. 1, 2015, pp. 5

[6] Kerry, Paul E. “Mary Wollstonecraft on Reason, Marriage, Family Life, and the Development of Virtue in a Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” BYU Journal of Public Law, vol. 30, no. 1, 2015, pp.. 17

[7] Kreis, Steven. “Mary Wollstonecraft, 1759-1797.” The History Guide, 13 Apr. 2012, www.historyguide.org/intellect/wollstonecraft.html

[8] Janes, R. M. “On the Reception of Mary Wollstonecraft’s: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 39, no. 2, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978, pp. 293

[9] Janes, R. M. “On the Reception of Mary Wollstonecraft’s: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 39, no. 2, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978, pp. 294

[10] Janes, R. M. “On the Reception of Mary Wollstonecraft’s: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 39, no. 2, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978, pp. 296

[11] Janes, R. M. “On the Reception of Mary Wollstonecraft’s: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 39, no. 2, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978, pp. 300

[12] Janes, R. M. “On the Reception of Mary Wollstonecraft’s: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 39, no. 2, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978, pp. 302