Was Eugène Delacroix the father of modern art?

22 February 2016

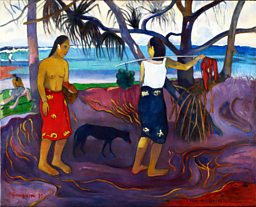

Eugène Delacroix was the leading artist of the French Romantic period, a master of colour whose painting and writing influenced Renoir, Manet, Pissarro, Gauguin, Cezanne and many others. WILLIAM COOK visits a new exhibition at the National Gallery in London, which asks whether modern art would have happened without him.

Would modern art have happened without Delacroix? That’s the question at the heart of this new show at London’s National Gallery. And on the evidence of these dynamic paintings, the answer is: no, probably not.

Delacroix was the enfant terrible of early 19th Century French art. He shunned the conservative conventions of France’s academic art establishment. A rebel with a cause, he inspired a generation of great artists. Impressionism and Post-Impressionism are inconceivable without him. ‘We all paint in Delacroix’s language,’ said Cezanne. ‘You can find us all in Delacroix.’

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism are inconceivable without Delacroix

Eugène Delacroix was born near Paris in 1798. Largely self-taught, he rejected the staid artistic standards of the age.

‘He felt, quite rightly, that you can’t teach genius,’ says Patrick Noon of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, who co-curated this exhibition (this show opened in Minneapolis last October, before travelling to London). ‘He was always at loggerheads with the Academy.’

Delacroix wasn’t interested in neat and tidy draughtsmanship. In an era obsessed with classicism, his expressive approach was avant-garde.

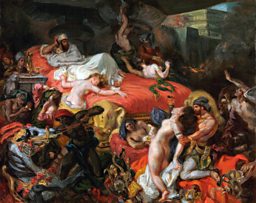

Delacroix’s paintings, like The Death of Sardanapalus, caused outrage. Today, it’s his graphic depictions of rape and murder that seem shocking. Back then, it was his loose brushwork and chaotic composition.

However Delacroix had no doubts. ‘When we look at nature, our imagination constructs the picture,’ he declared. His pictures created an intense relationship between the artist and the viewer. They were never meant to be refined objets d’art.

Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalus, 1846

Anyone mounting a Delacroix show is faced with the same problem. Many of his most important paintings are too frail and fragile to travel, so it’s almost impossible for any gallery outside Paris to assemble a comprehensive retrospective.

Masterpieces by Manet, Van Gogh and Gauguin... this show is full of great paintings. Who cares if they’re not all by Delacroix?

No wonder this is the first big Delacroix show in Britain for more than half a century, since the Edinburgh Festival exhibition of 1964.

‘We knew we couldn’t get these pictures – no-one can,’ says Noon. Rather than trying (and failing) to fill these gaps, he’s made a strength out of a weakness by focusing on the artists who idolised Delacroix.

Is this approach successful? On balance, I’d say yes.

Of course it’s frustrating not to see his greatest hits, but masterpieces by Manet, Van Gogh and Gauguin (among many others) more than make up for these absences. This show is full of great paintings. Who cares if they’re not all by Delacroix?

‘There’s something different in the way each artist approaches his work,’ explains Noon. ‘These are all artists who are looking to pursue what modernism is really about, which is the expression of your own experience – not what you were taught to paint.’

Like a modern rock star, Delacroix’s death cemented his mythic status

These young artists were inspired by Delacroix’s personality, as much as his paintings. Dashing and defiant, he was the first artistic rock star. He never married, he had no children. Even his true parentage was a mystery.

His complex character is captured in a splendid self-portrait, on loan from the Louvre. You can see why Baudelaire called him ‘a volcano artfully concealed behind a bouquet of flowers.’

Like a modern rock star, Delacroix’s death cemented his mythic status. After he died, in 1863, Cezanne painted a picture of him ascending into heaven, surrounded by his artistic disciples: Renoir, Monet, Pissarro and Cezanne himself.

Of course Cezanne was only joking – he didn’t really think Delacroix was Jesus Christ – but this playful painting illuminates an important truth. Cezanne realised all this adulation was a bit excessive, but he had no doubt that Delacroix was the father of Modern Art.

‘No-one under the sky has more charm and pathos combined than him, or more vibration of colour,’ he said. Delacroix showed these aspiring painters that art has no rules or boundaries. He gave them the self-confidence, the self-belief, to be themselves (‘Young artist, you want a subject? Everything is a subject. The subject is yourself’).

‘Every individual artist could find something that they could use,’ says the National Gallery’s Christopher Riopelle, co-curator of this exhibition. Artists like Paul Signac were fascinated by his use of colour, but it was his devil-may-care attitude which was the greatest inspiration.

Artists like Paul Signac were fascinated by his use of colour, but it was his devil-may-care attitude which was the greatest inspiration

His expedition to Morocco is a good example. He made countless sketches while he was there, but many of his best paintings were painted - brilliantly but inaccurately - years later, from memory. As Delacroix observed, it was important to forget the petty details, so as to recall the most striking and poetic aspects of each scene.

The posthumous publication of his journals introduced Delacroix to a new generation of artists, like Matisse and Kandinsky, whose paintings conclude this intriguing show.

Through these artists, his influence extended into the 20th Century. The last thing he ever wrote was a fitting summary of his art, and the art of his admirers: ‘The first merit of painting is to be a feast for the eye.’

Delacroix And The Rise of Modern Art is at the National Gallery, London until 22 May 2016.

Delacroix on BBC Radio

-

![]()

Free Thinking on Radio 3

Philip Dodd talks to curator Christopher Riopelle about the romantic pessimism of Eugene Delacroix: Listen now.

-

![]()

The Radio 2 Arts Show

Penny Smith and guests discuss the National Gallery’s exhibition Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art: Listen now.

-

![]()

Liberty Leading the People

Melvyn Bragg and his guests discuss Delacroix's painting Liberty Leading the People: Listen now.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms