The reign of Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici from 1587 until his death in 1609 was marked by three prominent weddings: his own to Christine of Lorraine in May 1589; that of his niece Maria de’ Medici to King Henri IV of France in October 1600; and that of his son Prince Cosimo de’ Medici (later Grand Duke Cosimo II) to Archduchess Maria Magdalena of Austria in October 1608. The festivities celebrating the 1589 and 1608 weddings culminated in the performance of a comedy (Girolamo Bargagli’s La pellegrina and Michelangelo Buonarroti il giovane’s Il giudizio di Paride) with spectacular intermedi before, between, and after the five acts of the play: indeed, the six intermedi to La pellegrina (1589) are widely regarded as a pinnacle of the genre, and the epitome of Medici court entertainments as political propaganda.

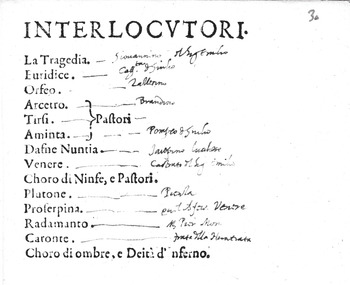

Something quite different occurred in 1600, however. Here the noble guests saw not a play with lavish intermedi but, rather, two through-composed “plays in music” – favole in musica (what we now call operas): Euridice, with words by Ottavio Rinuccini (1563–1621) and music in the main by Jacopo Peri (1561–1633); and Il rapimento di Cefalo, to a text by Gabriello Chiabrera (1552–1638) and music by Giulio Caccini (1551–1618) and others. For the Medici to celebrate a wedding of one of their own with a comedy and intermedi was to be expected: Duke Cosimo I (he became grand duke only in 1569) established the precedent with his wedding to Eleonora of Toledo in 1539, and the pattern continued through the celebration of the marriages of his son Francesco to Johanna of Austria (1565), and his daughter, Virginia, to Cesare d’Este (1586).Footnote 1 Opera, however, was different, and also confusing enough that at least one visitor to Florence in 1600 thought that Il rapimento di Cefalo somehow belonged to the older genre – though clearly it did not in terms of its structure and musical setting – perhaps by virtue of its mythological content and spectacular staging.Footnote 2 Euridice drew on Classical myth, too, but here, at least, there could be no doubt: something new was definitely in the air.

Michelangelo Buonarroti il giovane (1568–1646) had to tread a fine line in his official description of the 1600 festivities to place them at the apogee of this long tradition of Medici wedding celebrations.Footnote 3 But the grand duke and grand duchess (or their advisers) may have cultivated such novelty to mark the great political significance of a marriage (with the King of France, no less) that also marked an important shift in Medici foreign policy. Such novelty also suited the ambitions of the relatively young Florentine patrician, Jacopo Corsi (1561–1602), who was involved in putting Euridice on the stage. It was the culmination of a decade of theatrical experimentation in Florence, in which Corsi and others had been actively, and sometimes competitively, involved. They, in turn, built on theoretical investigations into ancient Greek and Roman music and drama going back several decades on the part of Florentine groups such as the “Camerata” sponsored by Giovanni de’ Bardi (1534–1612), also involving Vincenzo Galilei (1520–1591), Giulio Caccini, and Piero di Matteo Strozzi (1551–1614).Footnote 4 The Accademia degli Alterati in Florence had a role to play here, too: it was founded in 1569 and included a significant number of intellectuals and poets, such as Giovanni de’ Bardi, Lorenzo Giacomini, Girolamo Mei, and Giovanni Battista Strozzi il giovane, among many others. Although the academy barely met during the 1590s, it was briefly revived under the influence of Don Giovanni de’ Medici in late 1599–1600 (and again in 1604): Michelangelo Buonarroti il giovane, Jacopo Corsi, Piero di Matteo Strozzi, Alessandro Rinuccini, and Ottavio Rinuccini were among those who attended a session on 24 January 1599/1600.Footnote 5 Both Peri and Rinuccini made the connection with such humanist endeavor – as did Buonarroti for Il rapimento di Cefalo in his account of the festivities (he associates it with a revival of the power of ancient music to arouse the emotions of its listeners)Footnote 6 – although they also hedged their bets on the fidelity of Euridice to any Classical model.

That hedging was inevitable when squaring theoretical investigation with practical exigency. It also reflected a problem of genre. Peri and Rinuccini may have referred to ancient tragedy in their statements on Euridice, but they knew full well that they were also working within the more modern context of the pastoral play on the model of Tasso’s Aminta (1573) and Guarini’s Il pastor fido (1590), a genre that also gained considerable favor in Florence (and elsewhere) in the 1590s as a suitable medium for princely entertainment.Footnote 7 As Guarini discovered to his cost, the pastoral “tragicomedy” was controversial given its lack of Classical precedent and its apparent hybridity. But it had the further advantages of being relatively easy to stage (with fewer demands for complex scenery), and, still more, of offering a more conducive and plausible environment for music by virtue of its location in an idealized Arcadia where songs were naturally in the air. Various theatrical entertainments staged in Florence in the early 1590s inhabited the same mythological–pastoral world, including three (now lost) entertainments with texts by Laura Guidiccioni Lucchesini and music by Emilio de’ Cavalieri: Il satiro and La disperazione di Fileno in 1590 (or early 1591) and Il giuoco della cieca (based on an episode in Il pastor fido) in 1595. Grand Duchess Christine of Lorraine also seems to have favored pastorals as appropriate for women in her circles, whether as creators (for example, an untitled tragicommedia by Leonora Bernardi performed in villa in 1591, and Laura Guidiccioni’s collaborations with Cavalieri) or in terms of audience.Footnote 8 Thus although the first “opera,” Dafne – to verse by Ottavio Rinuccini and music by Jacopo Corsi and Jacopo Peri – was performed at Corsi’s residence in Florence in the presence of Don Giovanni de’ Medici in early 1598, it was repeated in the Palazzo Pitti before the grand duchess and Cardinals Francesco Maria del Monte and Alessandro Damasceni Peretti di Montalto on 21 January 1598/99.Footnote 9 That performance followed a revival of Cavalieri’s Il giuoco della cieca on 5 January (or, more likely, on the 4th).Footnote 10 Dafne may also have been staged at least once in 1600, if not necessarily with Peri’s music (see later in this chapter). Both events in Carnival 1598/99 took place in the Sala delle Statue, which, we shall see, had an impact on the preparations for the production of Euridice during the 1600 wedding festivities. The grand duchess and Don Giovanni de’ Medici made their influence felt here as well, the latter by being placed in some kind of charge of the celebrations as a whole.

These interconnections between the Medici and Florentine patricians were made particularly apparent in 1600 because of the political and other circumstances leading up to the wedding. But they also reflect a typical strategy of the Medici as a whole: although their rule as grand dukes of Florence was now undisputed, they were careful to foster patrician involvement in affairs of state, and were eager, of course, to showcase the intellectual and cultural vitality of their extraordinary city. Don Giovanni de’ Medici (1567–1621) served a particularly useful function in this light. He was the illegitimate son of Duke Cosimo I and Eleonora degli Albizzi, and was thus in a somewhat similar position to Don Antonio de’ Medici (1576–1621), born to Grand Duke Francesco and Bianca Cappello prior to their marriage in 1579. Both Don Giovanni and Don Antonio were subsequently legitimized within limits (and without rights of succession), and Grand Duke Ferdinando I tended to use them in various diplomatic capacities on ambassadorial missions abroad – Don Giovanni was often at the Spanish court – and as intermediaries to act in his interests in Florence and elsewhere. Don Giovanni had a distinguished military career (serving in Flanders, Hungary, and, later, on behalf of Venice), but when not abroad, he was active in Florentine intellectual and social circles such as the Accademia Fiorentina and the Alterati, given his own interests in the arts and sciences, as well as in the theatre. In addition he was an architect who played a leading role in designing military fortifications (for example, in Livorno and for the Fortezza del Belvedere in Florence) and churches (in Livorno, Pisa, and, somewhat controversially, the Cappella dei Principi in S. Lorenzo in Florence). In terms of his Florentine networks of associates and even friends, Don Giovanni was particularly close to, and cultivated by, Jacopo Corsi and Ottavio Rinuccini (they were roughly six and four years older than him, respectively). This created connections that would have a significant impact on the 1600 festivities.Footnote 11

Don Giovanni’s role in the celebrations appears to have generated some bad feeling between him and the venerable architect and stage designer, Bernardo Buontalenti, on the one hand, and, on the other, with Emilio de’ Cavalieri, who was notionally in charge of the court musicians but felt distinctly sidelined by the whole proceedings. Giulio Caccini also used the festivities to secure his reappointment to Medici service (on 1 October 1600) following his somewhat ignominious dismissal in 1593 (because of a dispute with Antonio Salviati over one of Caccini’s female students),Footnote 12 chiefly by way of Il rapimento di Cefalo but also, if to a lesser degree, by his involvement in Euridice. Meanwhile, Emilio de’ Cavalieri was becoming increasingly isolated from events in Florence, and the issues surrounding them, despite his supposed authority over the court artists and musicians. Not everything seems to have gone smoothly, but that might well be said of the wedding arrangements as a whole, however much Michelangelo Buonarroti il giovane tried to put a positive spin on things in his official Descrizione of the festivities, as he was required to do.

The Marriage Negotiations

Don Giovanni de’ Medici finds his typical place in the background of the well-known painting by Jacopo Chimenti da Empoli (1551–1640) of Maria de’ Medici’s wedding, or more properly, the ceremonial giving of the ring (see Fig. 1.1). This has all the hallmarks of such nuptial representations, and the absence of the groom, Henri IV, is not at all surprising: royal etiquette required the bride to meet him first on his terrain rather than hers. Thus Maria’s uncle, Grand Duke Ferdinando I (wearing the robe of the gran maestro of the Cavalieri di S. Stefano), stood as proxy for the king in the ceremony: Chimenti shows them standing to the left and right of Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini (nephew of Pope Clement VIII), the papal legate sent from Rome to officiate. They are bounded on either side by other members of the Medici family who, strangely enough, have consistently been misidentified in most scholarly accounts of this image.

Fig. 1.1: Jacopo Chimenti da Empoli, The Wedding of Maria de’ Medici and Henri IV of France (1600). Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi (Inv. 1890/10304).

Chimenti did the painting before, rather than after, the event: it was prominently displayed in the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio during the banquet on the evening of the ceremony, on the south wall (toward the Uffizi) and to the left of the baldachin over the head table at which was seated Maria de’ Medici, her immediate family, and the cardinal.Footnote 13 To the right was Chimenti’s representation (a mirror image, as it were) of the other royal “French” wedding involving the Medici, that of Caterina de’ Medici to Prince Henri, Duke of Orléans (later King Henri II) in 1533. To have yet another Medici as Queen of France was indeed a sign of greatness, so Grand Duke Ferdinando and Grand Duchess Christine must have thought.Footnote 14 For that earlier wedding, Chimenti had to draw on his imagination, but in his invoice for the two paintings submitted on 30 September 1600 (the week before the festivities), he made it clear that in the case of the current one he was representing those involved as they would indeed appear in the ceremony itself.Footnote 15 Buonarroti likewise wrote that the painting represented the ceremony officiated by Cardinal Aldobrandini “in the presence of those princes who had found themselves there that day.”Footnote 16 The one person that Chimenti could not paint from life, as it were, was the cardinal himself.

Chimenti listed in his invoice almost all the other persons shown, if not quite in the order they appear. Those he names, save Cardinal Aldobrandini, were Maria’s close family members, with women on the left and men on the right (Chimenti switched their positions in his “mirror” representation of the 1533 wedding). The viewer looking leftward from Maria de’ Medici sees, in order, the Duchess of Bracciano (Flavia Peretti-Orsini, peeping from behind Maria), Grand Duchess Christine, Prince Cosimo de’ Medici (he was ten years old), and the Duchess of Mantua (Eleonora de’ Medici, Maria’s elder sister). In the rear, between Maria de’ Medici and Cardinal Aldobrandini, is what seems to be a young nun, perhaps Passitea Crogi (from Siena), who acted as a spiritual adviser to the Medici women and, so it is sometimes reported, had prophesied Maria’s wedding to the King of France.Footnote 17 Looking rightward, the sequence is Don Antonio de’ Medici (Maria’s stepbrother, between the cardinal and the grand duke), Don Giovanni de’ Medici (her uncle), and the Duke of Bracciano (Virginio Orsini, her cousin).Footnote 18 The apparent prominence given to Virginio Orsini (on the far right) might seem strange, but of the three noblemen shown in this portion of the painting he was the only legitimate son of a Medici: he was Ferdinando I’s nephew by way of the grand duke’s sister, the ill-fated Isabella, who was murdered (most assume) by her husband, Paolo Giordano Orsini, Duke of Bracciano.Footnote 19 Chimenti’s “family” group – plus Eleonora de’ Medici’s husband, Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga of Mantua – acted as a cohesive unit throughout the wedding festivities, standing close by Maria during the ceremony in the Duomo, taking key positions in the banquet, and lunching together privately in the Sala delle Statue (or its antechamber) in the Palazzo Pitti on Sunday 8 October prior to the entertainment in the gardens of the Palazzo Riccardi in Via Gualfonda.Footnote 20

The typical need to present a unified front at the wedding also helped counter the fact that the negotiations leading up to it had been both long and difficult. Maria de’ Medici was born to Grand Duke Francesco and Johanna of Austria on 26 April 1575 and was now moving beyond the typical age for a dynastic wedding:Footnote 21 her sister Eleonora (born in 1567) was seventeen when she married Prince Vincenzo Gonzaga on 29 April 1584. Indeed, the first steps toward Maria’s union appear to have been taken when she herself was seventeen, as part of Cardinal Piero Gondi’s efforts to have Henri IV return to Catholicism; Gondi (the archbishop of Paris) traveled to Italy in 1592 to explore the possibilities with the Pope, stopping in Florence to arrange an incentive to aid the French king’s finances by way of the first of several large loans from Grand Duke Ferdinando I (made between 1592 and 1596, and repayable with interest) negotiated via the cardinal’s cousin, the Florentine banker Girolamo Gondi. This sowed the seeds of a further alliance, even though Henri was currently married to (if long estranged from) Marguerite de Valois, the daughter of Henri II of France and Caterina de’ Medici. Grand Duchess Christine also had her own family reasons for taking an active interest in favoring Henri IV as a means of ending the religious wars in France and neutralizing the increasing influence of the Duke of Savoy and his Spanish allies, a strategy brought to a head in the successful Florentine efforts to seize the Château d’If (off the coast of Marseilles) for Henri, in which Don Giovanni de’ Medici played a leading role. The king (re)converted to Catholicism in 1595, and his marriage to Marguerite de Valois was officially annulled in December 1599 following an agreement reached with her after the death of the king’s longtime mistress, Gabrielle d’Estrées, the previous April. Instrumental in that annulment were the pro-Florentine Cardinals del Monte and Montalto (the latter the brother of Flavia Peretti-Orsini, Duchess of Bracciano), bringing yet more Medici supporters into the fray. Meanwhile, for as long as Maria de’ Medici remained a pawn in this game of political chess, the grand duke resisted offers for her hand from Archduke Mattias of Austria and even from Emperor Rudolph II, as well as another that he considered derisory from Theodore, Duke of Braganza.Footnote 22

The grand duke and grand duchess clearly had broader political goals in mind by pursuing stronger relationships with France, not least as a counterbalance to Spanish influence on the Italian peninsula. But some significant pressure may also have come from Florentine patricians on more economic grounds, given that the French Wars of Religion, coupled with the death of Caterina de’ Medici in 1589, threatened their access to the lucrative financial and commercial markets there: the Gondi family’s extensive interests in Lyons were just one of many cases in point.Footnote 23 This is probably the reason why Jacopo Corsi, himself a prominent businessman, intervened personally with the grand duke on behalf of his fellow citizens to halt the arguments over the amount of Maria’s dowry and to offer their own financial support for it.Footnote 24 Henri asked for sc.1,000,000 whereas the grand duke was prepared to offer only sc.600,000. The negotiations were conducted by the Florentine ambassador to France, Baccio Giovannini (the grand duke feared that Girolamo Gondi was too partial to the French king), and in the end the Florentines paid only sc.350,000 in coin, with the remaining sc.250,000 deemed as credit for expenses incurred over Château d’If (sc.200,000) plus the unpaid remainder of a loan made to the French crown by Grand Duke Cosimo I. That coin was delivered on Maria’s arrival in Marseilles on 13 November 1600 by Bardo Corsi, Jacopo’s brother.Footnote 25

It seems clear that Ottavio Rinuccini was no less motivated by self-interest in securing his involvement in the wedding celebrations. Scholars have tended to associated it with an attempt to gain a position at the French court (Henri IV later named Rinuccini a gentilhomme du roi), although the poet had more pressing financial concerns in mind: in 1555, the Rinuccini bank had lent some sc.120,000 to Henri II (Caterina de’ Medici’s husband) – as part of a much larger loan negotiated with a consortium of European bankers – but the capital and much of the interest was never repaid and had more or less been written off. Ottavio Rinuccini made several trips to France between 1600 and 1605 (staying at Girolamo Gondi’s residence in Paris) and eventually managed to negotiate restitution to the tune of sc.53,000, which was considered more than satisfactory given the general difficulties faced by Florentines when dealing with French debtors.Footnote 26

The marriage negotiations still dragged on. Henri IV’s agreement to have Nicolas Brûlart de Sillery, his counselor of state and the French ambassador to Rome, conclude the marriage contract was sealed in Paris on 6 January 1600, but he only arrived in Florence in April, and in the meantime the French and Florentines were still arguing over the amount of the dowry.Footnote 27 The contract was signed in the presence of the grand duke, Virginio Orsini, Belisario Vinta (the grand duke’s primo segretario), and the archbishop of Pisa, Carlo Antonio Dal Pozzo, in the Palazzo Pitti on 25 April, the day before Maria’s twenty-fifth birthday. It was announced officially on 30 April, the eleventh anniversary of Grand Duchess Christine’s entrance into Florence: the grand duke met with the Florentine senate and leading patricians in his rooms in the Pitti, while cannon fire and bells sounded through the city. Events that day also included a procession to the church of SS. Annunziata to render thanks before the image of the Blessed Virgin, returning via the Corso toward S. Trinita and stopping at the residence of Jacopo Corsi, where “many gentlemen” engaged in tilting at the ring.Footnote 28 There was also a banquet in the Sala delle Statue for the grand duke and grand duchess, Don Giovanni and Don Antonio de’ Medici, and the Duke and Duchess of Bracciano, where Maria was granted ceremonial recognition according to her new status as a queen.Footnote 29

That same day (30 April), the grand duke wrote to Eleonora de’ Medici, Duchess of Mantua, that his intention was to hold the Florentine festivities, and hence Maria’s departure for France, before the season was too hot and bothersome (stagione troppo calda e noiosa) – that is, before the summer – and on 10 May the grand duke appointed five deputati to oversee the planning in terms of providing lodgings, servants, and stables for the most important visitors and their retinues: the deputati were required to meet daily, and to submit regular reports.Footnote 30 However, Baccio Giovannini’s voluminous correspondence reveals that the grand duke’s intentions were misplaced. Between the end of April and mid-May, Giovannini wrote repeatedly to convey Henri IV’s different plans in mind: a spring wedding was not possible given the king’s efforts to resolve his conflict with Carlo Emanuele I, Duke of Savoy, over the Marquisate of Saluzzo (eventually decided in the duke’s favor by the Peace of Lyons in 1601); Grand Duchess Christine was pregnant (with Maria Maddalena, born in late June); Maria could not travel in the hot summer months, and therefore she could not arrive in Marseilles before September, which Henri then started pushing back to October. It also becomes clear that Henri considered the Florentine announcement of Maria’s elevation premature on the somewhat dubious grounds that he might die in battle or by some other means in the interim, at which point she could not become Queen of France.Footnote 31 The grand duke may have won the battle over the dowry, but the king had the upper hand over the schedule. News of these delays was withheld in Florence until 22 May, however, and even then it was suggested that the wedding would likely take place in August, given that the king could not meet Maria in Marseilles before the end of that month: in fact, he never did (the king received her in Lyons in early December).Footnote 32 Even in September, the exact date of the Florentine festivities remained unclear, this time because Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini was delaying his departure from Rome.Footnote 33

Those involved in planning the 1600 wedding entertainments may have been glad of the delay: Euridice was probably well in hand by April 1600 and may even have had some kind of performance in the Palazzo Pitti in late May, although some significant questions remain over that (we shall see). Plans for the principal entertainment for the celebrations to be given in the Teatro degli Uffizi appear to have changed. Bernardo Buontalenti designed a set of six intermedi for which he built a model of the stage: the sets included a cityscape, an amphitheatre, the burning of Troy, a maritime scene, a garden (for the wedding of Hercules, presumably to Hebe), and as the last intermedio, an eagle giving birth to the Virtues.Footnote 34 There is no indication of which play was intended to be performed with these intermedi,Footnote 35 though as we have seen, the format would have fit the typical pattern of Medici wedding entertainments. However, Don Giovanni de’ Medici seems to have intervened to force a change to a quite different type of work: Gabriello Chiabrera’s Il rapimento di Cefalo was not a set of intermedi (despite persistent scholarly attempts to read it as such) but, rather, an opera sung to music throughout. Don Giovanni had tussled with Buontalenti in other contexts, too, and he would continue to do so (for example, over the construction of the Cappella dei Principi in S. Lorenzo), although in the case of Il rapimento, he eventually forced Michelangelo Buonarroti il giovane to remove any reference to himself in connection with the work.Footnote 36

The order to prepare Il rapimento di Cefalo appears to have been given only in early July 1600, which meant working to a very tight schedule, even for Florentine artists and artisans accustomed to the format of such festivities.Footnote 37 In the case of Girolamo Bargagli’s La pellegrina and its spectacular intermedi staged on 2 May 1589 for the marriage of Grand Duke Ferdinando I and Christine of Lorraine, the detailed notes left by Girolamo Seriacopi (provveditore delle fortezze) on the construction of the sets date back eight months, to 31 August 1588.Footnote 38 Emilio de’ Cavalieri and Giovanni de’ Bardi, who had been directly involved in the 1589 festivities but were marginalized in 1600 (Bardi had moved to Rome in 1592) under pressure from younger figures now close to Grand Duke Ferdinando, certainly felt that the 1600 entertainments did not reach their level. In several letters written from Rome in November 1600, a somewhat embittered Cavalieri wrote that the banquet and its decorations were held in high regard: he was biased, given that he had provided the music for the entertainment staged within it, a dialogue between Giunone (Juno) and Minerva, to a text by Battista Guarini. But in the case of Il rapimento di Cefalo, he said, few felt that the scenery, machines, and music had made any great effect, and as for Euridice, the music had not given satisfaction – though other reports say that it did – and the scenery was “unfinished” (per non esser terminate).Footnote 39 Likewise, Giovanni de’ Bardi complained to Cavalieri about the “tragic texts and objectionable subjects” of the 1600 entertainments, and when he was later given the task of arranging the festivities for the marriage of Prince Cosimo de’ Medici and Maria Magdalena of Austria in 1608, he reverted to the typical model of a comedy with intermedi, and he insisted on the need for adequate rehearsal specifically to avoid things turning out as they had done eight years before.Footnote 40 Cavalieri’s public response to those negative reports, he said, was to blame the shortage of time. But both he and Bardi clearly felt they would have done better.

The 1600 Festivities

Princely wedding festivities necessarily had certain fixed elements embracing both the sacred and the secular; they also tended to combine “public” events for the general populace with those for a more restricted audience (including distinguished guests) as well as “private” ones for closer family members. But even the family was on public display – Jacopo Chimenti’s painting of the wedding makes the point clear – and those entertainments to which the public did not have access were later published, as it were, by way of printed descriptions, librettos, musical scores, and other such sources.Footnote 41 Michelangelo Buonarroti il giovane’s official Descrizione delle felicissime nozze … della Cristianissima Maestà di Madama Maria Medici, Regina di Francia e di Navarra appeared some six weeks after the festivities (the dedication to Maria de’ Medici is dated 20 November 1600), and only after it had been carefully vetted by court officials and revised accordingly.Footnote 42 But it provides a day-by-day account of the celebrations up to Maria de’ Medici’s embarkation from Livorno (by ship to Marseilles), plus a list of the patricians who played a role in the ceremonies, and the text of the Dialogo di Giunone e Minerva performed at the banquet.

Buonarroti begins his account of the festivities themselves with the entry into the city on 4 October (a Wednesday) of Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, who conducted the wedding ceremony in the Duomo the next day, then the ceremonial baptisms of Grand Duke Ferdinando and Christine of Lorraine’s most recently born sons, Filippo and Lorenzo.Footnote 43 That evening there was a banquet in the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio, rich with additional decorations for the occasion. The banquet was preceded by dancing, and also included at its end the dialogue of Giunone and Minerva, who emerged on ceremonial chariots from grottoes built into the room.Footnote 44 On the evening of Friday 6 October, Jacopo Corsi’s offering for the festivities, Euridice, was staged in the Palazzo Pitti; the next day saw a palio run through the streets of Florence (and in the evening, an open rehearsal of Il rapimento di Cefalo);Footnote 45 and on Sunday 8 October, the court paid a visit to the famous gardens in the Palazzo Riccardi (in Via Gualfonda) for another entertainment arranged by a prominent patrician.Footnote 46 On Monday 9 October, the court visited the Uffizi Gallery and watched an acrobat walk a tightrope across the Piazza della Signoria from the tower of the Palazzo Vecchio to the statue of Grand Duke Cosimo I.Footnote 47 Then at sunset (le 24 hore) began the performance in the Teatro degli Uffizi of Gabriello Chiabrera’s Il rapimento di Cefalo, with music in the main by Giulio Caccini, although some polyphonic choruses were provided by other of the city’s musicians, including Stefano Venturi del Nibbio, Piero di Matteo Strozzi, and the maestro di cappella of the Duomo and S. Giovanni Battista, Luca Bati.Footnote 48

Buonarroti inevitably devoted most space in his description to the banquet (some ten pages) and Il rapimento di Cefalo (nineteen), whereas the entertainments provided by Florentine patricians were given far less (just over one page in the case of Euridice). In terms of the banquet, the Salone dei Cinquecento was the principal civic space for such celebrations, while the Teatro degli Uffizi was the typical location for grand theatrical entertainments for Medici celebrations: designed by Bernardo Buontalenti, it was inaugurated in February 1586 with the performance of Giovanni de’ Bardi’s comedy L’amico fido and its spectacular intermedi during the festivities for the wedding of Virginia de’ Medici and Cesare d’Este, and it was remodeled for La pellegrina and its intermedi in 1589. Otherwise, however, the theatre was used very infrequently: for more routine entertainments (for example, during Carnival), the Medici tended to prefer more intimate, private spaces, whether in the Palazzo Pitti or, by the early seventeenth century, in the accommodations elsewhere in the city allocated to Medici princes, including the Palazzo del Parione, occupied by Don Giovanni de’ Medici, and the Casino di San Marco, the official residence of Don Antonio de’ Medici from 1598.Footnote 49 This was a matter of function on the one hand, and decorum on the other: the Medici grand dukes were careful to separate the “private” and “public” aspects of their ceremonial lives. It also raises broader, and important, questions about how the Medici configured and used different indoor and outdoor locations available to them for courtly and related functions, as well as matters of financing such pastimes from public or private funds.

Some tricky matters of protocol ensued. It was by no means unusual for Florentine patricians to contribute to Medici celebrations, whether individually or as part of a group such as the Accademia degli Alterati: indeed, it was a smart tactic enabling them to secure, and to demonstrate, grand-ducal favor. Some of them (including Jacopo Corsi) paid a share of the costs of the sbarra held in the courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti on 11 May 1589, during the festivities for the wedding of Ferdinando I and Christine of Lorraine, and the practice continued on less formal occasions during the 1590s.Footnote 50 Both Euridice and the festa held in the gardens of the Palazzo Riccardi during the 1600 festivities were par for the course. However, a counter-example reveals some of the issues. The Accademia degli Spensierati (associated at other times with theatrical activity in Florence) wished to stage an entertainment for the wedding, and one of its members, Francesco Vinta (a nephew of Belisario Vinta, the grand duke’s powerful primo segretario), pursued plans to mount a performance of the tragicommedia, L’amicizia costante, by Vincenzo Panciatichi (a cavaliere di S. Stefano). The play was printed by Filippo Giunti with a title page saying that it was dedicated to Maria de’ Medici on the occasion of her wedding to Henri IV, although there is no actual dedication in the print (see CWFig. 1.8): the license for the printing is dated 26 April 1600.Footnote 51 In August 1600, however, Vinta was still searching for a location for a possible performance, and was distinctly unhappy with the offer of the Teatro della Dogana, the “public” theatre in Florence used by the comici dell’arte, because the academy considered it undignified.Footnote 52 In November 1600, the Giunti press printed a new first signature (A) of Panciatichi’s play that replaced the one in the first state of the edition: it had a different title page, this time stating that the play was indeed staged during the wedding festivities, plus a dedication from Panciatichi to Vinta (dated 4 November) noting that it was performed in the presence of Maria de’ Medici and of other principal guests foreign and domestic (see CWFig. 1.9).Footnote 53 However, there is no mention of any such performance in Buonarroti’s description of the festivities, nor in any other court record to be found.Footnote 54

The surprising thing about Euridice, then, is not so much that Jacopo Corsi was allowed to present it as part of the festivities, but that he could do so within, rather than outside, the Palazzo Pitti. Clearly Corsi had more clout with the Medici (or at least, with the grand duchess and Don Giovanni) than Francesco Vinta, whether because of his contribution to the marriage negotiations or given his previous track record of providing entertainments within the palace (including, of course, his Dafne during Carnival 1598/99). Buonarroti tried to keep the record straight, however, in his account of Euridice, wording matters quite punctiliously: Jacopo Corsi had it set to music with great learning (con grande studio); very rich and beautiful costumes were prepared; the work was offered to, and accepted by, the grand duke and grand duchess; and a noble stage was constructed in the Pitti.Footnote 55 Even so, the seemingly unusual circumstances created confusion among court officials who one might expect (perhaps wrongly) to have known better. For example, Cesare Tinghi, the grand duke’s aiutante di camera, called Euridice “a pastoral comedy in music done by Signor Emilio de’ Cavalieri” (una comedia pastorale in musica fatta dal signor Emilio del Cavaliere).Footnote 56 This was an understandable mistake. Cavalieri was a musician who had been brought to Florence from Rome in 1588 to serve as the superintendent of the grand duke’s Galleria dei Lavori (Gallery of Works, covering a range of artistic and similar enterprises), and who had overseen almost all the theatrical entertainments held in the Palazzo Pitti and the Medici villas in the 1590s. He certainly had some indirect involvement in Euridice, but nowhere near as much as those working in the grand-ducal administration apparently assumed.

Buonarroti’s carefully worded account of the genesis of Euridice also reflects how it was funded, so far as we can tell. The common assumption that Corsi’s provision of the work for the 1600 festivities meant that he also paid for it is not, in fact, borne out by the sporadic references to it in his own account books, such as they survive. Certainly he was responsible for the music (in the sense of commissioning it), and probably also for the singers and instrumentalists (he was one of the latter), although whether he or anyone else actually paid them any money is another matter.Footnote 57 He also seems to have covered at least some costs of the costumes, as would have been typical of any patrician involved in Florentine entertainments: an inventory of Corsi’s effects prepared after his early death (on 29 December 1602) includes, among items for entertainments and mascherate, costumes for Orpheus and for Pluto, as well as ten for nymphs (and three for Furies, who do not appear in Euridice unless they are generic characters of the Underworld).Footnote 58 As for the stage constructed in the Pitti, however, this fell to the Medici household, which paid for the scenery and covered other costs associated with the sets.Footnote 59

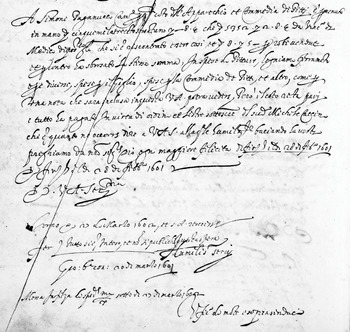

The Medici’s financial accounts for Euridice, and for the wedding banquet held in the Palazzo Vecchio, were very carefully kept separate from those for the more public celebrations of the 1600 wedding festivities (Il rapimento di Cefalo, the triumphal arches for processions through the streets, and so forth), and the grand duke ordered that they be kept secret (et non si pubblichi questa spesa, see Fig. 1.2).Footnote 60 In part, one assumes, this was because he did not wish to be accused of extravagance. But it was also a question of the source of the funds supporting these various events, whether from the privy purse (the grand duke’s camera) or the public treasury.Footnote 61 As is typical of the grand-ducal administration – and the funding streams that supported it – affairs of state were one thing, and “private” matters another, even when it came to seemingly official entertainments.

Fig. 1.2: SS 279, fol. 144 v (bottom half); the review of expenditure on Euridice audited by the Ufficio di Monte e Soprassindaci, 28 February 1601/2. The instruction “not to make public” this expense is on the fifth line up from the bottom.

Whether the funding was kept so strictly separate in actuality (that is, in terms of disbursements) is a separate matter; accounting is one thing and the real world another. However, the well-known Florentine obsession with keeping proper account books (which had significant legal status in Tuscan law) brings with it several distinct advantages. The surviving giornali, libri di entrata ed uscita and di debitori e creditori, and the like that now fill the archives offer an unparalleled view of life at all levels of Florentine society. Many more, of course, are lost, or were destroyed once they had fulfilled their purpose: this is particularly true of low-level accounts and supporting documents intended to be subsumed in higher-level ones. Indeed, the survival of the materials presented in this book seems to be more a matter of chance than design. But they enable a close reconstruction of Euridice as it was conceived and performed.

Two Invoices and an Inventory

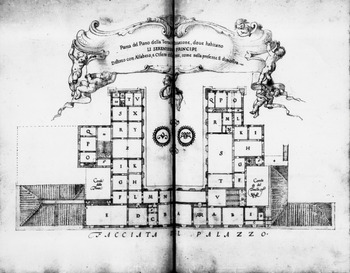

Arranging a royal wedding was a massive undertaking, not just in terms of ceremonies and entertainments but also given the need to provide accommodation for the large number of official guests invited to Florence for the occasion. This was a perpetual headache for the five deputati appointed on 10 May 1600 to oversee these aspects of the festivities: they also needed to select boys to carry the baldacchini in various processions; to find representatives from various Tuscan towns to act as attendants; and eventually to arrange the ten-day holiday declared by the grand duke (on 22 September 1600) so that the populace could give proper signs of devotion, reverence, and joy.Footnote 62 Other officials were temporarily appointed to take charge of specific aspects of the festivities. But three others also played leading roles by virtue of their position as permanent heads of particular administrative bodies: Donato dell’Antella, superintendent of the grand-ducal fortresses and buildings (sopraintendente delle fortezze e fabbriche); Vincenzo Giugni, keeper of the Guardaroba (he was usually styled the guardaroba maggiore or guardaroba generale); and Vincenzo Medici, head of the Depositeria Generale (the office in charge of grand-ducal finances). Broadly speaking, dell’Antella’s office had charge of all manner of construction and maintenance concerning the grand-ducal buildings, while the Guardaroba (the “wardrobe”) was responsible for everything they contained: furniture, utensils, clothing, etc., as well as works of art. Both offices kept detailed accounts from the day-to-day level up – as, of course, did the Depositeria Generale – in addition to making regular inventories of their holdings both for monitoring purposes and as needed for the succession from one head administrator (or grand duke) to another.

Understanding such administrative structures is important given that it enables one to navigate the various archival fondi that survive (although some do not) as witness to the operations of these various offices. The strict record-keeping typically required of them in Florence further aids the archival historian, given that particular actions can usually be tracked through the various branches of the system. However, events or actions outside the norm of the regular activities or responsibilities of such offices – or that involved more complex interactions between them – tended to fall between the archival cracks as it would not be clear which office should end up with what in its files. Wedding festivities certainly met that “outside the norm” standard: they were straordinari rather than ordinari. They also involved more directly the leading members of the Medici family, which could lead to lines of communication becoming crossed or confused: hence the rather shadowy presence of Don Giovanni de’ Medici in the 1600 festivities without any clear statement apparent in the archives about his precise role. Thus the documents concerning Euridice and the banquet discussed here were placed among the records of the Guardaroba once their original purpose had been fulfilled, but the Guardaroba administrators did not quite know what to do with them, which is probably why they ended up (much later) in a somewhat haphazard miscellany of materials from 1575 to 1739 (GM 1152) labeled Affari diversi. These documents were originally part of a file (filza) of 229 receipts (ricevute) collated and numbered on 28 November 1601 and connected with the “book of the banquet and royal wedding of the Most Christian Queen of France.”Footnote 63 This “book” – presumably of accounts – does not survive, so far as we know. Nor do we have the other account books to which cross-references are made here, including a stracciafoglio de’ Pitti, a quaderno delle feste (and a libro delle feste, if that is not the same item), a libro della reale commedia (Il rapimento di Cefalo), and what would probably have been a master ledger covering the whole festivities (identified as “A”):Footnote 64 these kinds of documents are typical of Florentine accounting systems, ranging from a low-level waste book (the stracciafoglio, recording daily transactions) to higher-level records in more summary form. However, the cross-references in these receipts are sometimes useful to determine which item was allocated to which purpose (the banquet, Euridice, or some other heading).

A significant number of the ricevute are just slips of paper acknowledging the delivery of construction materials (timber, canvas, hardware, etc.) to carpenters and other artisans working in the Palazzo Pitti. Most of the timber came from the Fortezza da Basso, the principal storehouse of construction materials for military or civil use, and so was under the control of capitano Gianbattista Cresci, the chief provisioner of the fortress(es) – he is variously styled provveditore della fortezza, provveditore del castello, and provveditore delle fortezze – who reported to Donato dell’Antella.Footnote 65 Cresci further supplied laborers (carpenters, plasterers, etc.) when needed. This made sense: the Fortezza da Basso was the obvious source for such materials and labor, and Cresci’s predecessor, Girolamo Seriacopi, had fulfilled the same function for the 1589 wedding festivities, leaving records rich in information on them. Cresci also needed funds to cover his costs. Thus, on 13 May 1600, Donato dell’Antella submitted an order (mandato) that the administrators of the Fortezza da Basso be allocated a sum of money for day-to-day expenses in preparing the festivities, to be kept in a separate account: the grand duke approved sc.1,000 on 14 May, and the money was assigned from the Michelozzi & Ricci bank on 16 May; additional money was requested on 22 June (another sc.1,000 were allocated on 26 June), and further advances were made once the order was given on or about 13 July to prepare Il rapimento di Cefalo.Footnote 66 All this money was drawn down by Simone Paganucci, Cresci’s treasurer (camerlengo del castello).

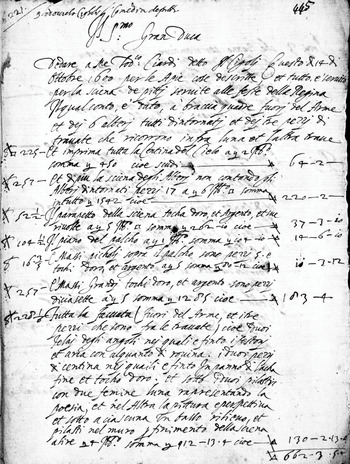

Cresci, in turn, assigned these materials to his subordinate, Michele Caccini (no relation to the singer, Giulio), who had been seconded from his position as provveditore of the Fortezza del Belvedere to take charge of the banquet and of what became known as the commedia de’ Pitti, that is, Euridice.Footnote 67 Caccini was therefore required to keep detailed accounts both of any financial transactions and of the receipt or disbursement of materials. He was also the direct point of contact for the artists and artisans involved in the construction of whatever was needed for these two events. It was to Caccini that the painter Lodovico Cardi detto “Il Cigoli” submitted his invoice for designing and painting the stage and scenery for the opera, on 14 October 1600 (see Fig. 1.3).Footnote 68 The invoice is transcribed and translated in Appendix I.A.

Fig. 1.3: GM 1152, fol. 445; Lodovico Cigoli’s invoice (first page) for creating the set for Euridice, 14 October 1600.

Lodovico Cardi was commonly known as “Cigoli” after his birthplace in Tuscany, near San Miniato al Tedesco. His involvement as stage designer for Euridice has been known for some time through surviving documents and some sketches by him that appear related to it (discussed in Chapter 2), but not to the extent discussed here.Footnote 69 He had studied first in Empoli and, from 1574 to 1578, was apprenticed to the artist Alessandro Allori in Florence, with whom he collaborated on decorations for the Galleria degli Uffizi. After a period in the early 1580s back in the provinces, Cigoli returned to Florence to work under the architect (and stage designer) Bernardo Buontalenti; he also studied with Santi di Tito. Typically for his profession he was both an architect and an artist. His subsequent output included architectural designs for the facade of S. Maria del Fiore, decorations for the Uffizi and the Palazzo Pitti, and a large number of works commissioned by the Medici as well as by other private individuals and religious institutions across Tuscany.Footnote 70 From 1604 he was based largely in Rome (in part under the patronage of Virginio Orsini, Duke of Bracciano), where he received numerous other commissions, although he returned at times to Florence. He is considered to be one of the more significant painters of the Florentine early Baroque school.

The purpose of Cigoli’s invoice is obvious enough: he sought payment for work done, itemized in eleven entries (Cig1–11) and amounting to a total of sc.758 £3.5s.4d., including sc.25 because of a change of rooms for the performance (as we shall see). Cigoli submitted it on Saturday 14 October. This appears to have been a typical day of the week for Medici officials to reckon their accounts, so Michele Caccini met with Cigoli there and then to go over the document. He agreed on the extent of the work listed in it, as he wrote in a comment added at its end, but he clearly had concerns over Cigoli’s prices. There was a typically Florentine game being played here, where artists and artisans inflated their costs, in part to take account of the reduction in price (as a result of the tara) that the Medici conventionally expected for products or materials procured from those who regularly worked for them.Footnote 71 Administrators were obliged to query such charges, and, usually, a compromise was reached by some manner of negotiation. The rules were well enough understood on both sides, to the extent that Medici officials could be sympathetic enough to compensate those who somehow neglected to apply them. This seems to have been the case with Jacopo Ligozzi, whose invoice for creating the gigantic lily (giglio) as decoration for the banquet was deemed by Gianbattista Cresci and Donato dell’Antella to be too low (sc.329 rather than the expected sc.370, down by 12.5 percent), prompting payment of the additional sc.41 in addition to a one-time “gift” (donativo) of sc.200 for his services.Footnote 72 But in Cigoli’s case, Michele Caccini was not going to authorize payment to Cigoli without some further investigation, and he commissioned five other Florentine painters to provide costings for the same work, item by item (see CWFig. 1.10).Footnote 73 This was his standard practice in such circumstances: it also raises important questions about how the market worked in terms of the value assigned to artists and their output.Footnote 74 From those five estimates, Caccini took an average of the lowest four that enabled him to negotiate downward: on 19 February 1600/1, Cigoli was credited with sc.379 £3.9s.8d., which is almost exactly half of what he originally requested. The fact that this sum was calculated down to the level of soldi and denari, however it might have been achieved, is surely a nicety to do more with appearances than with reality. But those appearances mattered, as did the well-tuned system which produced them. The fact that Cigoli accepted the lesser amount, as did other artists in similar situations, suggests that everyone knew how to play the game so as to achieve a (mostly) fair result, satisfactory to all sides.

It is important to remember that all these sums are calculated in terms of moneys of account: how they translated into actual payments in coin, in kind, or by some form of credit, is a separate issue. Nevertheless, such conscientious reckoning was expected of any administrator. It also contradicts the common image of spendthrift rulers engaging willy-nilly in luxury consumption without regard for the consequences: the Medici grand dukes certainly spent money on luxuries befitting their station and duties, but did so with some care on the part of their officials.

Michele Caccini had other obligations as well, given that all the materials he procured for the banquet and Euridice were credited to his account. In effect, they became a “debt” that needed to be “repaid” or somehow written off. After the dust had settled on the 1600 festivities, Caccini was therefore required to close his account by transferring the materials he had received – or what had been made of them – to another account not within his present domain (even if it might have stayed under his control under a different heading). This is the reason for the second document concerning Euridice presented here (Appendix I.B): an inventory, dated 18 September 1601, of the stage and its sets as placed in storage in space next to Teatro degli Uffizi, and therefore moved both literally, from one place to another, and figuratively within the accounting system. Whereas Cigoli’s invoice covers only those elements of the stage and sets for Euridice with which he was directly involved, this later inventory of the materials used for the staging is more comprehensive, at least in terms of what remained a year after the production, or that had not already been used for other purposes.

This inventory was prepared on behalf of, and signed by, Gianbattista Cresci, although it was written out by a scribe in his office, Matteo Chelli (see CWFig. 1.11).Footnote 75 But its forty-two entries (Cres1–42) were compiled on the basis of a (now lost) document completed by Caccini himself on 4 September listing the materials that he had deposited in storage. He identified them in quite precise terms even down to the different types and forms of timber used to construct the stage. The aim was to transfer these materials to the account of the administration of the “royal comedy” of the 1600 festivities (Il rapimento di Cefalo). Thus the inventory is, in effect, an annotated copy of Caccini’s list, or perhaps even a copy of a copy (that had been entered into the new account). But Cresci needed to arrange an audit of those materials to confirm that Caccini’s list was correct (or to note discrepancies therein), and to provide Caccini with a version of it that would act as written confirmation of his deposit, canceling his “debt.”

Not everything used for Euridice was moved to the Uffizi. Items that had been “borrowed” from the Guardaroba (some boards and trestles) were sent back there, while the large coat of arms that Cigoli placed at the center of the proscenium arch had now been mounted above a staircase in the Palazzo Pitti. Cresci noted everything accordingly, both to keep the record straight and as a reminder in case items needed to be retrieved should the grand duke wish to restage the opera (per ricordo di ritornare dette robe se mai Sua Altezza Serenissima volesse fare rimettere insieme detta prospettiva per recitare detta comedia). Some of the construction materials suitable for other purposes had already gone elsewhere, as in the case of the wood from the ceiling and other parts of the temporary stage, which had been used to build a stanzino in one of the grand duchess’s rooms in the Palazzo Pitti (this wood therefore entered a different account relating to the palace). Other items were missing or damaged beyond repair, something which Cresci appears to have accepted as normal, given that he wrote them off rather than pursuing Caccini to remedy matters. As for the rest of the stage and sets, should Caccini or anyone else have needed them again (we shall see in Chapter 4 that someone did), a new account would have had to be opened operating in similar ways.

All this paper-pushing was laborious, but it had the advantage – at least in principle – of knowing not just where everything was at any given moment, but also who was responsible for it. To judge by Cresci’s inventory, Caccini’s original list had also been fairly methodical in its sequence of different elements of the stage. But how the line-items in any such accounts otherwise squared with reality both before and after the fact is another matter altogether. For example, there was no way for Cresci to ascertain that Caccini’s list included absolutely everything he had originally procured for Euridice. In other words, there may have been other materials for the production that Caccini chose not to include, or that got diverted elsewhere in ways not otherwise recorded in surviving documents: this has a bearing on whether Cresci’s inventory (relying on the list) identifies everything needed to reconstruct the staging. However, the fact that Caccini deposited at least some damaged items suggests that he was extremely conscientious, as would be expected of any good administrator.

The invoice and the inventory needed to be accurate enough to serve their purposes and to meet appropriate standards of verification. Such accuracy was needed for some details more than others, however: a case in point is items listed in bulk, such as Cigoli’s claim for painting the stage floor, measuring 104.5 b.q., although he did so by way of painting an unspecified number of separate pieces of canvas (that may or may not then have been stitched together) amounting to that total area (not all of which survived, according to Cresci’s inventory). For Cigoli’s purposes that level of specificity did not matter (he painted what he painted), just as any eventual loss of the material was not his concern (Cigoli had done the work and needed credit for it). Nor would Cresci necessarily have been aware of the discrepancy unless he were to go back and check an invoice that by then was probably kept in a different place. But it would hardly have mattered if he had: Cigoli was paid in February 1601, whereas Cresci’s inventory was made seven months later.

Similar circumstances and caveats apply to the other invoice considered here. Cigoli’s charges included the cost of some materials (the colors, gold leaf, and other manufacture pertaining to the painter, so he noted at the end of the invoice), but not all of them. The canvas on which he painted the proscenium and sets was included within a long invoice submitted by Francesco Ricoveri materassaio (mattress maker) reflecting his contribution to the festivities since 20 May 1600 (see CWFig. 1.12).Footnote 76 Large amounts of canvas were delivered to the Palazzo Pitti, some “old” from the Fortezza da Basso and the Teatro degli Uffizi, and some newly procured from other sources. In both cases this canvas then needed to be sewn (cucito), that is, with strips joined together or hemmed (or both). A great deal was needed for the decoration of the Salone dei Cinquecento for the wedding banquet: in addition to new figurative paintings and the scenic elements created for the banquet itself, the walls of that room were almost entirely covered by temporary hangings that concealed the large frescoes by Giorgio Vasari and his assistants done in the third quarter of the sixteenth century, presumably because their subjects – the victories of Florence over Pisa and Siena – were considered indelicate for the occasion. However, Ricoveri also sewed canvas and performed other tasks that can be associated specifically with Euridice; the relevant entries (Ric1–17) are given in Appendix I.C. The invoice itself is undated (as are its separate items), but it was prepared sometime shortly after the wedding: the account was settled on 10 November 1600.

Not all the canvas used for Euridice passed through Ricoveri’s firm: for example, on 25 August, Michele Caccini received 110 b.q. per servitio della comedia de’ Pitti from storage in the Teatro degli Uffizi, possibly intended for the stage floor (measured by Cigoli at 104.5 b.q.).Footnote 77 Moreover, items in Ricoveri’s invoice do not always square precisely with what was delivered: for example, the receipt (dated 11 September 1600) for the 150 b.a. of canvas for the “sky” (tela pagliola … per il cielo della prospettiva della commedia de’ Pitti) says that it was made up of four pieces, whereas Ricoveri’s invoice lists eight.Footnote 78 Nor do we know whether that canvas delivered on 11 September had already been painted by Cigoli (it did not matter so far as Ricoveri was concerned), although the relatively late date would suggest that it had. But the relatively close correlation, as regards the canvas, between Ricoveri’s invoice and Cigoli’s (and what survived according to Cresci’s inventory) suggests that Ricoveri was working with materials that had already been fashioned with the measurements of Cigoli’s design in mind. Like Cigoli, he, too, needed to accommodate the change of room for the performance of Euridice, sewing the additional canvas needed to cover the enlarging of the stage, and the widening of the proscenium. And he was one of two artisans present in the Palazzo Pitti on the day of the performance on 6 October (the other, we shall see in Chapter 2, was the lanternaio, responsible for the lighting), probably in case his services were needed for any urgent repairs.

Although Ricoveri’s measurements are given in what he calls braccia, it seems that his charges for sewing canvas were calculated by the braccia andante, that is, a cumulative series of lengths (for example, the four sides of a rectangle added together): he charged a fixed rate of £1 per 10 b.a. (2s. per b.a.), and, for any other labor in his shop, £3.10s. per person per workday (though he himself charged £7 for attending the performance of Euridice). A single piece of canvas (a telo) could be sewn together with other such pieces (to produce a tela). If needed (for example, for vertical scenery), the tela could then be mounted on a frame (a telaio). Thus, when Ricoveri sewed together eight pieces of canvas (eight teli) for the “sky” of the stage to produce what Cresci identified as a single tela measuring 17 b. long and 13.5 b. wide “on average” (ragguagliata, Cres8) – and assuming that those eight teli created the total width (so each telo was some 1.7 b. wide) – he hemmed two lengths at 17 b. each and two at 13.5 b. each, and sewed seven joins: this gives a total of 155 b.a. The fact that Ricoveri charged for 150 b.a. (Ric6) is a relatively minor discrepancy on a par with the one between Cresci’s measurements (17 × 13.5 = 229.5 b.q.) and Cigoli’s (he measured the sky at 225 b.q., Cig1); indeed, the differences are negligible bearing in mind that Cresci’s measurements here were “on average.” Other discrepancies in Ricoveri’s invoice are probably due to his sometimes sewing more canvas than was needed (in case of wastage) or adding an allowance for construction purposes: for example, tele mounted to a telaio needed some extra length and width so that their edges could be wrapped around the frame.Footnote 79

The elements of Ricoveri’s invoice pertaining to Euridice amounted to £294.12s., representing just under 40 percent of his total for the festivities (£755.4s.), although the tara brought that final total down by over half to £361.16s.Footnote 80 The sums credited to Cigoli (eventually) and claimed by Ricoveri amount to sc.421 £5.1s.8d. (sc.379 £3.9s.8d. + £294.12s.), although Ricoveri would have received less as a result of the tara. The final cost of those elements of Euridice that fell under the jurisdiction of Michele Caccini (and hence the Fortezza da Basso) was reported by Gianbattista Cresci to be sc.678 £0.16s.: the difference is presumably due to other costs for materials and labor, although there is scant reckoning of them in the surviving documents.

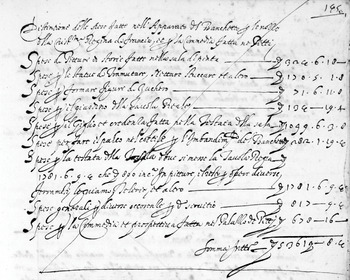

Cresci submitted a final accounting of his total expenditure for the 1600 festivities in February 1601/2 to the administrators of the Ufficio di Monte e Soprassindaci – the office in charge of auditing all official and public expenditures – which they reported to the grand duke on 28 February (see Fig. 1.4).Footnote 81 Cresci’s total for the banquet and Euridice together was sc.5,361 £0.8s.4d. – he also provided a breakdown, including a separate line per la commedia et prospettiva fatta nel Pitti – and for Il rapimento di Cefalo, sc.5,925 £5.3s.4d.Footnote 82 The grand duke approved this reckoning on 27 March 1602, and that approval was conveyed to Cresci on 16–17 April.Footnote 83 The cost to Cresci of Euridice (sc.678 £0.16s.) presumably does not represent the entire amount of the opera: for example, as we have seen, the costumes were probably covered by Jacopo Corsi, and there is no evidence of direct payment to the singers. However, the total somewhat palls in comparison with the sc.1,781 £6.9s.4d. spent on decorating the royal table and its surrounds at the head of the banquet in the Salone dei Cinquecento (including around sc.800 for paintings), plus sc.1,099 £6.3s.8d. for its giglio, credenza, and other decorations, and sc.134 £0.19s.4d. for its centerpiece.

Fig. 1.4: SS 279, fol. 145 (top half); the breakdown of the costs for the banquet and Euridice audited by the Ufficio di Monte e Soprassindaci, 28 February 1601/2.

This final accounting came quite late in the day, and it took a while to grind through the system. Clearly there was no urgency in closing out the paperwork; nor need there have been, so long as it was done properly in the end. But Cresci was not left waiting until April 1602 for reimbursement of (or credit for) his expenditures. As we have seen, he was given two allocations each of sc.1,000, the first in mid-May 1600 and the second in late June. He kept a weekly tally of expenses on the banquet and Euridice that would draw down this sum, beginning with the week ending on Saturday 20 May; on 1 September, he reported to one of the court secretaries, Marcello Accolti, that according to this tally up to 26 August (he enclosed a copy broken down by week and heading), the original sc.2,000 had been overspent (by just over sc.145), meaning that additional money was needed.Footnote 84 Cresci also noted that significant payment requests were still to come in because most of the artists and artisans involved would submit invoices only after their work had been completed. The total spent on Euridice by 26 August was sc.309 £2, which had increased to sc.450 by 13 September 1600, so Cresci wrote to Accolti that day. Cresci’s principle concern, however, was the cost overrun for the various scenic and other elements of the banquet: he had already transferred sc.220 of the total money allocated for Euridice to pay some of those bills, although this needed to be reimbursed, given that his juggling of the books contravened the order given by Don Giovanni de’ Medici that money budgeted for the opera should not be used for other purposes.Footnote 85

Francesco Ricoveri was paid only on 10 November 1600, but it seems from Cresci’s figures (and from the eventual total cost to him of Euridice at sc.678 £0.16s.) that Cigoli received some payments, or at least credits, in advance for his work. This is also apparent in upper-level accounts held by the Guardaroba: Cigoli was allocated sc.18 on 9 June 1600, then near-regular weekly credits (calculated at what seems to have been sc.15 per week) from 21 July to 9 September, adding up to sc.138.Footnote 86 The purpose of these payments is not specified here, although some can be squared with other Guardaroba accounts: the 9 June payment was for pitture fatte a carrozze (presumably, for carriages), while the ones on 21 July (sc.20) and 25 August (sc.15) were for other “pictures.”Footnote 87 Cigoli was working for the Palazzo Pitti on items other than just for Euridice; he also did at least one of the paintings used to decorate the walls of the Salone dei Cinquecento for the wedding banquet.Footnote 88 It seems reasonable to assume, however, that at least some of these payments represented advances on the costs of the design and painting of the sets for the opera. Thus, when Cigoli was “paid” sc.379 £3.9s.8d. on 19 February 1600/1, there would have been some reckoning of what he had already received by way of a different account.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind one key difference between the three main documents discussed here. Cigoli’s and Ricoveri’s invoices reflect work done, or materials delivered, up to the point where that work or those deliveries ceased. Ricoveri’s last day on the job was 6 October 1600 (he was present at the performance). Cigoli’s, however, was presumably sometime sooner: as the performance approached, it was left to Matteo imbiancatore (an artisan who often painted walls, etc. in the Palazzo Pitti) to provide for “the blue part of the sky,” which probably means touching it up in places.Footnote 89 Cresci’s inventory, on the other hand, reflects what was actually used for and in the 6 October performance, in whatever state it survived once the stage had been dismantled, including items not covered by Cigoli and Ricoveri. To recreate the original staging of Euridice, the inventory is more useful than those invoices, even if the latter sometimes help explain what the inventory contains.

The Performance of “A Comedy by Signor Jacopo Corsi” (Spring 1600)

The payments for what Cresci tended to call the commedia de’ Pitti, beginning in the week ending 20 May 1600, are part of a broader pattern as the Medici set plans into action for the forthcoming festivities once the marriage was officially announced on 30 April. Rumors about Corsi’s “new pastoral” had in fact been circulating for several weeks: on 7 April, Emilio de’ Cavalieri (then in Rome) grumbled to Marcello Accolti about his having heard of many Florentines being told that it would be something “heavenly” (si è dato conto già a molti fiorentini di una pastorale nuova che fa il signor Jacomo Corsi, che dicono che sarrà cosa celeste), although Cavalieri, no friend of Corsi and his collaborators, was distinctly unimpressed by the hyperbole, feeling that the heavens and angels were being done a severe injustice (poveri cieli et angeli).Footnote 90 It was a particularly bitter pill to swallow because just two days earlier Cavalieri had complained to Accolti about the unfavorable comparisons being made between his Il giuoco della cieca and Rinuccini’s Dafne (both performed in the Pitti in January 1598/99), and between the Easter celebrations held in 1600 against those of the previous year (in which Cavalieri had been more directly involved); he was also annoyed by the praise now being given to Giulio Caccini (as “the god of music”) and other comments being made in favor of musicians other than those supported by him.Footnote 91

As for Rinuccini, and in the context of what was becoming a heated competition between various Florentine literary and musical figures, the poet was anxious to assert the prominence of Dafne as moving beyond Cavalieri’s pastoral experiments toward a more plausible reconstruction of ancient theatrical practice in terms of structure and delivery. A libretto had already been printed, probably in relation to the Carnival 1598/99 performance (the revised prologue refers to the grand duchess, who was present), but with a poorly typeset title page and some errors in the text (and, it seems, without the licenza from the religious authorities that would normally be required for anything made “public”).Footnote 92 The Marescotti press then produced a more elegant edition of La Dafne d’Ottavio Rinuccini rappresentata alla Serenissima Gran Duchessa di Toscana dal Signor Iacopo Corsi dated 1600 (after 25 March, given that Marescotti used stile fiorentino dating in his prints): it bears the arms of Christine of Lorraine on the title page (but otherwise lacks any prefatory material) and ends with an ode in praise of Corsi (“Qual novo altero canto”).Footnote 93 Rinuccini associated this edition of Dafne with the one of Euridice issued by Cosimo Giunti in anticipation of the performance during the 1600 wedding festivities, although the date of its dedication to Maria de’ Medici is left incomplete (it specifies the month – October – but the day is left blank) as if the date of the performance itself was still unclear at the time of printing (probably because of the uncertain schedule for the wedding, for reasons already noted).Footnote 94 In that dedication, Rinuccini refers to his having published both librettos because of the warm welcome being granted to such musical productions (Là onde, cominciando io a conoscere quanto simili rappresentazioni in musica siano gradite, ho voluto recare in luce queste due …); this might further suggest that the librettos came out in relatively close proximity. As we shall see, he also made a direct connection between Dafne and Euridice by way of the latter’s final chorus. But by this time, Rinuccini’s account in the dedication of Euridice to Maria de’ Medici of the creation of both operas may also have been intended to counter the claims for priority in the “invention” of opera being made (by Alessandro Guidotti) in the dedication to Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini of Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s sacred opera, Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo, published in Rome by Nicolò Mutii in early September (the dedication is dated the 3rd) following its performance there the previous February. Cavalieri certainly read Rinuccini’s comments in that competitive light.Footnote 95

That 1600 edition of Dafne acknowledges some performance of the opera before the grand duchess – as occurred during Carnival 1598/99 – but does not say when that was. It also commemorates her role (by virtue of the title page) and gives credit to Jacopo Corsi (the ode) in ways not possible in the printed libretto of Euridice, which was perforce dedicated to Maria de’ Medici. But the uncertainties surrounding the Dafne edition add to a number of problems in interpreting an important document concerning the 1600 festivities in the file of ricevute kept by Michele Caccini. On 9 June 1600, one the Palazzo Pitti’s carpenters, Camillo di Benedetto Pieroni, issued a request to debit the grand duke a total of £30.10s. for work on the construction of a “stage” that the grand duchess had requested be built in the salone of the Duchess of Bracciano in the Pitti, and which had served “to perform a comedy by Signor Jacopo Corsi” on 28 May (a Sunday).Footnote 96 (It is not clear whether 28 May was the date of the performance, as the wording suggests, or of the grand duchess’s order to prepare for it.) Pieroni charged for two days of labor – a Monday and a Tuesday – for him and three garzoni (one of whom worked just for a single day) for erecting the stage, and for half a day for him and two garzoni to take it down on 6 June (a Tuesday). The wood could have been drawn from the consignment Pieroni had received on Saturday 13 May to adjust the height of various statues in the Pitti and for other purposes (per servitio di calare figure a Pitti, et altri affari),Footnote 97 or the one obtained on Tuesday 16 May to make a residenza, probably in the Sala delle Statue.Footnote 98 But if we accept 28 May as the date of the performance, Pieroni’s invoice suggests that the stage went up on 22 and 23 May, and was left standing for two weeks.Footnote 99

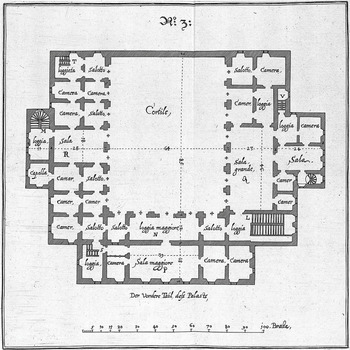

Adapting spaces in the Palazzo Pitti for multiple purposes, including theatrical ones, was typical of the flexible ways in which many rooms were used in the palace: it made better sense than restricting them to a single function, and labor came cheap. Bernardo Buontalenti also created a model for a temporary theatrical stage that could be installed and dismantled as required within the palace.Footnote 100 In the present case, there are two obvious problems to be solved: identifying Corsi’s “comedy,” and the location of the performance. For the former, the question is whether we are dealing with another performance of Dafne or, instead, some manner of preview of Euridice that the grand duchess wished to vet for the festivities.Footnote 101 For the latter, the issue concerns the rooms in the Palazzo Pitti occupied by the Duchess of Bracciano, and therefore the position of any salone that Camillo Pieroni would have associated with her.

The fact that the court diaries and similar documents are silent on any theatrical performances or similar events in late May or early June does not help matters. In fact, this was a fairly quiet time in the Palazzo Pitti. Grand Duke Ferdinando I was away from Florence in villa, leaving the grand duchess behind, and as was customary she kept him abreast of things by way of regular letters. She and Maria de’ Medici also seem to have reserved that last weekend in May for some manner of planning for the wedding festivities, which Grand Duchess Christine may further have intended as a distraction from the stressful circumstances around the marriage negotiations and their repeated delays: indeed, on 28 May the grand duke emphasized that Maria was not to be kept informed of those circumstances precisely because they might cause her too much anxiety.Footnote 102 Thus on Saturday 27 May the grand duchess wrote to her husband that the previous evening she had spent some time with Maria discussing the color scheme of the livery for the pages, footmen, guards, and carriages attending her at the wedding, deciding in the end, she says, for what was known in French as orange, bleu, celeste, et blanc. The grand duchess included in that letter a sample of Maria’s favorite color (presumably in cloth) that Ferdinando was to pass on to the King of France.Footnote 103 It then emerges from the grand duchess’s next letter, written the following day, that the poet Battista Guarini was in attendance (she writes that he would leave “tomorrow” – Monday), which would have allowed some discussion of the proposed entertainment for the wedding banquet (Guarini wrote the text for the Dialogo di Giunone e Minerva).Footnote 104 However, there was also a rather tricky diplomatic issue to be resolved. As the grand duchess wrote in her Saturday letter, the papal nuncio had appeared at the Palazzo Pitti earlier on Friday bearing a breve from the Pope and letters from Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini. The nuncio was requesting an audience with Maria de’ Medici, but the grand duchess was uncertain about the etiquette for allowing it, given that she was unclear as to what the Pope’s breve contained: presumably the lack of such knowledge threatened to put the women in a compromising position if some quick response were needed. Ferdinando must have replied immediately, because in her Sunday letter the grand duchess said that she would indeed arrange an audience for the nuncio “today.” It is not clear how this might have affected any performance of Corsi’s “comedy” taking place that same day, if it did (Christine does not mention it in any letter).

Jacopo Corsi seems to have been even busier at the end of May: his household accounts include an entry for the 30th referring to expenses involved in hosting guests for four days at his villa in Sesto Fiorentino.Footnote 105 This may or may not be connected to a visit to Florence made by the Benedictine monk, Angelo Grillo, sometime between late April and early June as he traveled from the capitolo generale of his order in Parma, which began on 24 April, back to the Monastero di S. Scolastica in Subiaco, east of Rome (he was its abbot from 1599 to 1602). Grillo was a prolific poet of both spiritual and secular verse (he published the latter under the name Livio Celiano), and his voluminous correspondence reveals extensive connections with a wide range of literati and musicians.Footnote 106 During what he called his lungo passaggio in Florence, Grillo was able to renew acquaintances with the poets Giovanni Battista Strozzi il giovane (who also played a leading role in the Accademia degli Alterati) and Ottavio Rinuccini, and with the musician Giulio Caccini, as is clear from letters he wrote to them after his return to Subiaco (where he arrived on 15 June); this sequence further includes a letter to Jacopo Corsi, whom Grillo seems to have met in Florence for the first time.Footnote 107 His Florentine encounters appear to have extended to other members of the Alterati – or at least, to their works – and his visit also led to several requests for him to write poetry in honor of Maria de’ Medici’s wedding, although Grillo gracefully declined, claiming not to be able to set his mind to it.Footnote 108