Plastic will be the likely calling card of our time on Earth when modern sites are excavated by future researchers. And plastic is leaving its mark at historic sites as well, according to a new study.

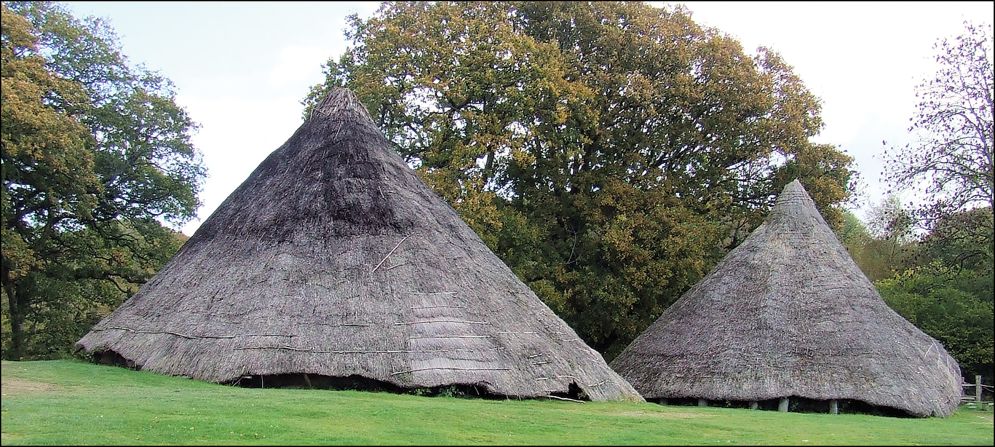

Castell Henllys is the site of an Iron Age village in the Welsh Pembrokeshire Coast National Park. It was once home to a wealthy family that included a community of up to 100 people who worked together to produce food and materials 2,000 years ago.

The rural site of the hill fort includes four reconstructed roundhouses, which are circular structures with conical roofs made of wood and straw. Archaeologists and researchers rebuilt these structures using the same materials villagers would have used during the Iron Age.

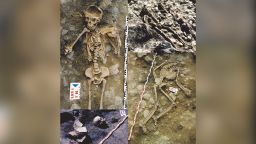

Based on extensive excavations at the site, the roundhouses were reconstructed using the foundation trenches and post holes of the original structures.

“This is the only site in the UK where this has been done and has been open to the public and schools for over 35 years,” said Harold Mytum, lead researcher and professor of archaeology at the University of Liverpool, via email. “This means that the reconstructed houses have stood for a long time, showing how effective the prehistoric designs were.”

Two of the roundhouses, the Cook House and the Earthwatch house, were replaced in 2018 and 2019.

After standing for nearly 30 years each and being visited by countless tourists and about 6,000 school children per year, the sites of the roundhouses provided a unique opportunity for researchers.

What began as an experiment to understand how building materials decay and degrade over time turned into something else when the researchers uncovered a wealth of plastic – 2,000 plastic items to be exact.

The study published this week in the journal Antiquity.

Although the historic site is well maintained and cleaned, small plastic remnants of activity by visitors – children routinely eating lunches in one of the structures – were able to hide beneath benches in dark corners of the roundhouses.

The site is in a very rural setting among the rolling countryside of west Wales, so “the amount of plastic litter was a surprise,” Mytum said.

While plastic is one of the main sources of marine pollution, this study shows its impact on the terrestrial environment as well, the researchers said.

Among the plastic fragments were utensils, bottle caps, straws, straw wrappers, plastic bags, plastic food wrap, candy wrappers and even apple stickers.

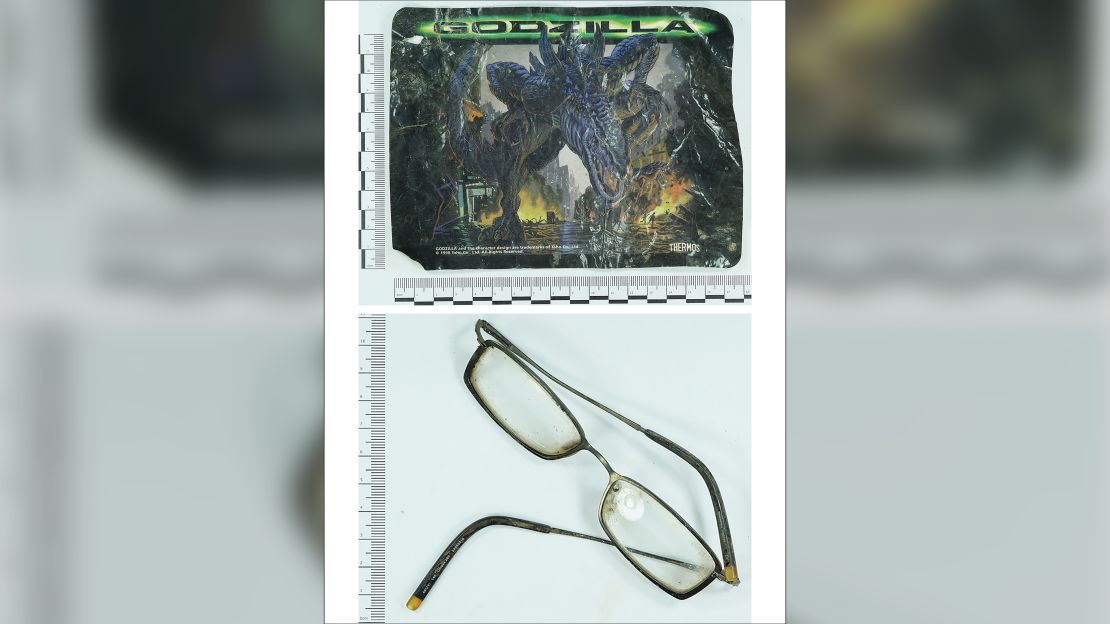

They even found “an almost complete Godzilla-themed thermos wrapper.”

“If (the children) had been given (sack lunches) without all the plastic packing it would have made a huge difference,” Mytum said. “Our convenience can lead to environmental damage.”

Other items are related to heritage interpretations given at the site.

Costumed guides represent the Demetae tribe which once inhabited this part of Wales before, during and after the Romans invaded. Role playing and activities are part of the experience, including cooking and weaving and face painting of Celtic designs. Several plastic face paint containers were also uncovered.

And then, of course, there were items likely lost by children at the site: a pair of glasses and articles of clothing.

“We thought we would find items that were lost during the use of the houses, but the amounts were disturbing in their environmental implications,” Mytum said. “To find that here gives the site a new importance – it shows how our plastic discards affect everywhere.”

Their findings are indicative of what researchers believe will be the hallmark of the Anthropocene, the current geological age, and that our tine will come to be known as the “Plastic Age.”

“The plastic creates an archaeological signature of our time (the Anthropocene), but one which is environmentally damaging,” Mytum said. “That plastic will enter the ecological cycle and have wider implications. If all this material was recycled, it would not be represented archaeologically but would help save the planet ecologically.”

Mytum is working with the staff at the historic site to increase environmental awareness for future visitors and will use the evidence they collected during the excavations to create an educational campaign.

“This shows that carefully planned reconstruction on excavated areas can provide very effective public interpretation and education facilities, and test theories about building construction,” Mytum said. “It also shows, though, that even when it appears that the site is well maintained and litter collected, much may still be deposited. Management of what is sold in site shops and allowed on-site could help reduce entry of plastic into the terrestrial environment.”