The ceremonial center of the ancient Zapotec city of Monte Alban. Photo by Arthur Joyce.

A CU-Boulder anthropologist and a collaborator from Florida have won a $230,000 grant to examine the role of religion in the social and political innovations that led to the emergence of Mesoamerican civilization.

Arthur Joyce, professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder, and Sarah Barber, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Central Florida, have won a Religion and Innovation in Human Affairs grant, which is funded by the John Templeton Foundation.

For some time, Joyce contends, archaeologists have under-emphasized the role of religion in the development of complex societies. The researchers favor a broader view, he says.

“We see religion as being important in constructing newer forms of centralized political organizations,” Joyce observes. At the same time, he and Barber are exploring why religion and political structures evolved differently in four regions of ancient Mesoamerica.

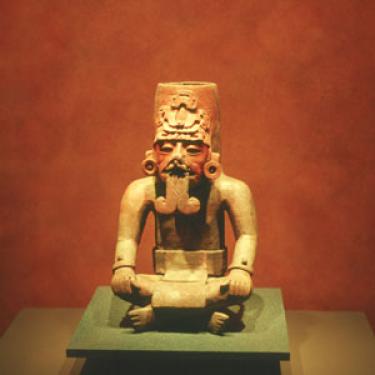

Zapotec urn depicting a Rain God impersonator. Photo by Arthur Joyce.

The researchers are planning a three-month archaeological field project in the lower Río Verde valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. They also plan archival research in the Archivo Técnico of theInstituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia in Mexico City.

Drawing on their field and archival work, Joyce and Barber plan to co-author a book examining the role of religion in the social and political innovations of Formative period Mesoamerica, which spanned 1900 B.C. to A.D. 300.

The field research in the lower Río Verde is important because it addresses an instance in which political centralization was unstable and short-lived; learning more about this episode provides an opportunity to explore how religion may have motivated resistance to or hindered political innovation, the researchers write.

Scholars need to broaden their understanding of the interrelationships between religion and cultural change at this time in Mesoamerica because many of the features of religion and political organization encountered by the Spanish in the 16th Century crystallized during the Formative period, Joyce and Barber write.

Scholars recognize that religion was important in legitimizing political authority, but little attention has been given to the ways in which religion generated major innovations in political organization, they write. Instead, religion often has been treated as secondary to economic and political innovations.

“Our project will redress this gap by identifying commonalities and differences in the ways that people used religion to creatively work through the problems of political centralization.”

Joyce and Barber note that characteristics of Mesoamerican civilization that were developed and refined during the Formative period include fundamental tenets of religious belief, practice, and worldview; artistic and architectural canons; social inequality and its ideological underpinnings; and political authority and the terms by which it was legitimated.

The researchers’ analysis of four regions of Mesoamerica will consider when, where and why religions are promotional, neutral or repressive toward innovation.

“Current evidence suggests that religion may have been a major generator of innovations in political organization among Mexico’s Gulf Coast Olmec but a significant means of contesting political innovation in the lower Río Verde valley of Oaxaca.”

Joyce and Barber will compare and contrast religion and political centralization in the Gulf coast, the Oaxaca Valley, the lower Río Verde Valley and the Soconusco coast in Formative Mesoamerica.

The project, titled “Religion and Political Innovation in Formative Mesoamerica,” plans to augment excavations carried out in 2012 in the Río Verde valley of Oaxaca funded by the National Science Foundation.

The project includes collaborations with a geoarchaeologist, a physical anthropologist, a web-designer/e-learning specialist, along with the participation of nine American and Mexican students.

The first draft of the book, titled “A Comparative History of Religion and Politics in Formative Mesoamerica,” is scheduled to be completed in 2014.

Joyce has been a member of the CU-Boulder faculty since 1999.

It is an “important, fascinating topic,” Joyce says, adding that the RIHA grant is a “fantastic opportunity.”