What do you think?

Rate this book

316 pages, Paperback

First published August 1, 1979

Everything one used to take for granted, with so much certainty that one never even bothered to enquire about it, now turns out to be illusion. Your certainties are proven lies. And what happens if you start probing? Must you learn a wholly new language first?

"Humanity". Normally one uses it as a synonym for compassion; charity; decency; integrity. "He is such a human person." Must one now go in search of an entirely different set of synonyms: cruelty; exploitation; unscrupulousness; or whatever?

(p 161)

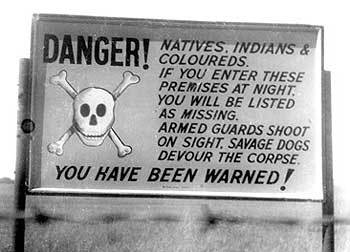

Nothing in this novel has been invented, and the climate, history, and circumstances from which it arises are those of South Africa today. But separate events and people have been recast in the context of a novel, in which they exist as fiction only. It is not the surface reality that is important but the patterns and relationships underneath that surface. Therefore, all resemblance between the characters and incidents in this book and people and situations outside is strictly coincidental.First published in 1979, this is a story of Apartheid in South Africa. How can one not have known of the systematic racial discrimination of the time? We outsiders knew it was wrong, but did we actually realize its full extent? No. I did not see the movie made from this book.

It is very quiet in the office. There are steel bars in front of the window. It hits you in the solar plexus. Suddenly you realise that the friendly chap with the curly hair and the safari suit hasn't turned a page in his magazine since you arrived. And you start wondering, your neck itching, about the thin man in the checkered jacket behind your back.Finally, Brink presents some diary or journal entries written by du Toit. These, of course, are in the first person. In another author's hands, these changes would be annoying, but here it is done masterfully. I could not have been more aligned with du Toit, even though the narrator was male rather than female.

“Io non penso di aver mai veramente saputo, prima. O, se sapevo, non mi sembrava che mi riguardasse direttamente. Era, come dire… il lato oscuro della luna. Anche se uno prendeva atto della sua esistenza non doveva necessariamente conviverci”

“[…] non è d’accordo con me che il senso, il vero senso di epoche come quella di Pericle o dei Medici sta nel fatto che un’intera società, in effetti, un’intera civiltà, davano l’impressione di muoversi alla stessa andatura, nella stessa direzione” […] “In un’epoca di quel genere, l’individuo non ha quasi mai bisogno di prendere delle decisioni per conto suo: la tua società le prende per te, e tu ti trovi in completa armonia con essa. D’altro canto, ci sono periodi come il nostro, quando la storia non ha ancora imboccato la sua nuova strada. Ogni individuo è solo. Ognuno deve trovare le proprie definizioni, e la libertà di ognuno minaccia quella di tutti gli altri. Qual è il risultato? Il terrorismo. E non sto parlando solo delle azioni dei terroristi addestrati, ma anche delle azioni di uno Stato organizzato le cui istituzioni mettono a repentaglio l’umanità stessa di ognuno.”