In November of 1936, the renowned magazine publisher Henry Luce launched a new periodical intended to transform his medium, one with a plain but evocative name for which he had purchased the rights from the publishers of an earlier and ultimately unsuccessful magazine: Life. Luce envisioned a publication in which large, eye-catching photographs would tell a compelling story, placing the focus on visual details instead of text. Naturally Life would require a crack team of photographers to realize this vision. Luce chose four leading practitioners for the first issue, and among them perhaps the most distinguished was also the only woman: Margaret Bourke-White, who had already made a name for herself at another one of Luce’s periodicals, Fortune.

She was born Margaret White in the Bronx in 1904. Her mother was a Roman Catholic of Irish descent, her father a Polish Jew and an engineer. While she enjoyed photography as a child, young Margaret only saw it as a hobby, and when she went to college her first idea was to study herpetology. A few classes with the self-taught photographer Clarence Hudson White changed her mind, however, and she ultimately graduated from Cornell University with a Bachelor of Arts degree. One year later she opened her own commercial photography studio in Cleveland, but White had no intention of making her living from family portraits or genre scenes. From the very beginning she focused on architectural and industrial photography, and the latter would come to be a quintessential aspect of her art.

As Margaret Bourke-White (a professional name she constructed from her maiden name and her mother’s maiden name), she set her sights on the many steel mills in Cleveland, finally gaining access to the Otis mill in 1929. Several observers at the mill were skeptical, as they considered the conditions too dangerous for a “lady photographer.” In fact, the heat was so intense that it threatened to melt her camera equipment, but Bourke-White was indefatigable in pursuit of a good shot. The resulting pictures, which she published privately that same year, demonstrate a new approach to industrial photography: heroic images focusing on the tough and efficient workers alternate with vast and imposing expanses of factory equipment and open space, while action shots of molten slag and jumping sparks dazzle the viewer’s eye like exploding fireworks.

Bourke-White’s audacious search for novelty ultimately paid off, as the unique photos attracted the attention of prominent figures like Henry Luce, who invited (some might say commanded) her to return to New York as the first staff photographer for Fortune magazine. Meanwhile a growing professional reputation led to unique opportunities for her own studio business; among other things, she was personally invited to the Soviet Union in the early 1930s to take pictures of industrial activity under the first Five-Year Plan. In a world that had almost no independent images of life in Soviet Russia, Bourke-White’s photos gained widespread recognition and made her a nationally recognized figure in the United States.

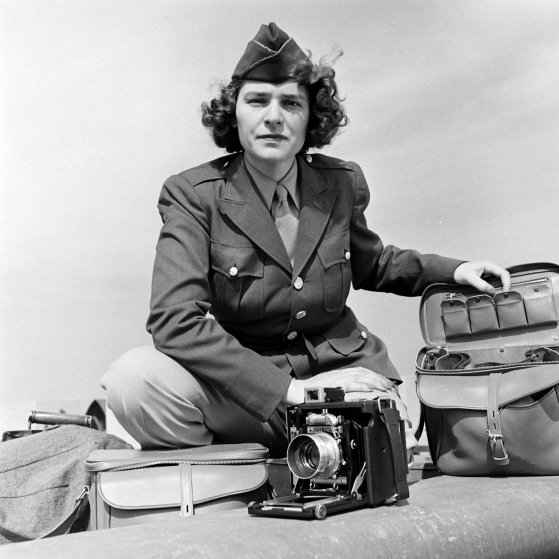

Photography in the ‘30s and ‘40s was not a job for the faint-hearted. From taking snapshots in front of roaring steel furnaces, Bourke-White moved to climbing skyscrapers for architectural pictures and covering the actions of soldiers and civilians in war zones. She was the first woman to act as a war photojournalist, bringing a personal view of World War II to readers back in the U.S. while facing the same dangers as a combatant. Back at home, she showed that her bravery was political as well as personal, capturing touching images of rural life in You Have Seen Their Faces, an expose of social troubles in the American South much in the vein of How the Other Half Lives.

Bourke-White’s industrial photography reflected the epic magnitude of factories geared toward mass production, while also building respect for the workers who grappled with huge machines and endless streams of raw material. Her architectural photography gave average people an up-close look at the remote, imposing grandeur of urban skyscrapers. Images of both daily life and unusual events from around the globe, captured by her, took the immense world that the United States was still struggling to take cognizance of and made it relevant and personal for the readers of magazines like Life.

Bridging gaps between cultures is a task we at Inclusity value very highly, and we know from personal experience how difficult it is. Bourke-White was not daunted by difficulty and followed her muse wherever it led: into factories, into battlefields, and into foreign lands.

Margaret Bourke-White is probably the first person in this series so far whose story cannot be adequately summarized by a few paragraphs of text. Seeing the photographs she took reveals her story far more eloquently than any biographical blurb could do. However, to give those images some additional context, we quote here the original brief Luce wrote to describe the purpose of Life magazine, a passage which also serves as a summary of Bourke-White’s accomplishments:

“To see life; to see the world; to eyewitness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things—machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon; to see man’s work—his paintings, towers and discoveries; to see things thousands of miles away, things hidden behind walls and within rooms, things dangerous to come to; the women that men love and many children; to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed.”

Next Post: George Shima, the Japanese-American “Potato King” who battled anti-Asian sentiment on the West Coast.<