Understanding Ludwig Wittgenstein: Deconstructing the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

*Disclaimer: the following piece of literature stands on its point of view and does not claim to be the only one right. All the words used by the author have been used reflectively and to the best in their power. Feel free to interpret the following in your own perspective.

Preface

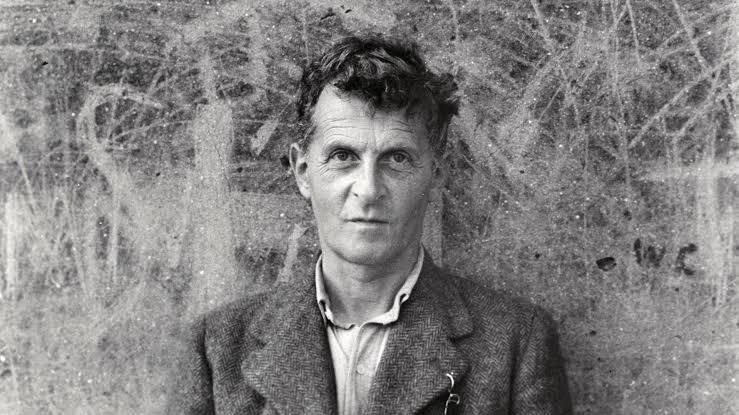

Ludwig Wittgenstein has often been heralded as one of the greatest minds of the early 20th century, primarily attributed to the writing and publication of his widely known magnum opus, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. The Tractatus, being the only full-length book publicized during his lifetime, marked a major turning point in the fields of linguistics, philosophy, logic, and mathematics as his work aimed to establish a relationship between language and the reality of the world against an overarching framework of logic and mathematics, thereby solving all philosophical problems in one succession by proving that no substantial claims can be made about reality. This article is written to explain and honor the fundamental ideas expressed through the Tractatus by deconstructing it under the lens of Wittgenstein and to provide a base interpretation of his early work. In addition, a personal interpretation of Wittgenstein’s work will be made by the author at the end, forming the main crux of the work as it stands true to itself.

Introduction and Background:

To analyze the work of any distinguished philosopher, we must first look at their upbringing and social background to see what possible influences they might have had to develop their particular line of philosophy. Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein, born on April 26th 1889, was born into a rather affluential Austrian family. His father, Karl Wittgenstein had a firm hold on the steel industry during that time, and his accumulated wealth resulted in them being the second wealthiest family in all of Europe during the late 19th century, second to only the Rothschilds. Being one of the nine children born to the Wittgensteins, Ludwig was raised as a stern Catholic against a Jewish background. Such a fact is evidenced in his writing and correspondence as he was extremely self-critical of his Jewish identity. There were many eccentricities clouding Ludwig’s childhood years, as he was homeschooled along with all his siblings. Karl Wittgenstein was, in all regards, an extremely strict father who wanted to prepare an appropriate heir to inherit the Wittgenstein family wealth. His line of reasoning for homeschooling his children was made in an effort to shield them from inheriting all the common pitfalls of society that were shared among the populace back then. This lasted till Ludwig reached the age of fourteen, after which he, along with his only surviving brother Rudi, were sent to a proper highschool. This occurred as a result of Karl’s lamentation regarding the suicide of two of his former sons owing to being brought up in such strict conditions. During his formative years, we see that Ludwig had a strong affinity for Christianity due to his firm upbringing, writing that,

“Is what I am doing really worth the labour? Surely only if it receives a light from above.”

~Wittgenstein: A Religious Point of View

This might be one of the reasons why Wittgensteinian thought is extremely dogmatic in its approach to deciphering reality, being heavily drenched in mathematics and logic. We later come to know that Ludwig’s firm sense of logical realism was developed partly due to being influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer by means of his work, ‘The World as Will and Representation’. Ludwig’s obsessive interest in mathematics and logic was preceded by him garnering an interest and studying aeronautics at the Victoria University of Manchester in order to pursue a doctorate for a brief period. Wittgenstein was introduced to the world of mathematics and logic as a result and his attention shifted elsewhere, particularly towards foundational mathematics. Such an interest was fueled by his reading of Bertrand Russell’s ‘The Principles of Mathematics’ and Gottlob Frege’s ‘The Foundations of Arithmetic’. It was around this time that Wittgenstein developed his philosophical line of thought, one that preached that all existential propositions are meaningless and that all philosophical problems were linguistic puzzles. Initially discussing with Gottlob Frege about his interest in taking up mathematics and later coming under the mentorship of Bertrand Russell, Ludwig frequently lamented about his gripes with logic and often felt depressed as a result, stating,

“What I feel is the curse of all those who have only half a talent; it is like a man who leads you along a dark corridor with a light and just when you are in the middle of it the light goes out and you are left alone.”

~Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911–1951

After the death of his father Karl Wittgenstein, Ludwig inherited the family fortune and started working and taking notes on a piece of work simply labelled as ‘Tractatus’. The Tractatus was the initial draft of what would later be known as the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. He first proposed that there were no logical propositions other than generalizations of tautologies, which were in turn generalizations of logic. Afterwards, he formulated that the fundamental problem of logic was to make a general truth function of all tautologies. He further clarified this point by stating that all tautologies were self-evident and appeared as tautologies by themselves. He later enlisted in the military at the start of World War 1 and continued to work on the Tractatus in the meantime. Although he submitted an initial draft of the Tractatus, it ultimately got rejected largely owing to its complexity and eccentric nature. In the following years, the Tractatus would garner much more interest in multiple fields of knowledge and be published under the name ‘Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus’ in 1921, a reference to Baruch Spinoza’s ‘Tractatus Theologico-Politicus’. Such an allusion made between works of contrasting knowledge was suggested by G.E Moore and accepted during publication.

The primary objective of the Tractatus was to establish a relationship between language and the world under the scaffolding of logical propositions in order to determine the limits of the world, i.e., what cannot be said and what can only be shown. Wittgenstein argues that the logical structure of natural language was inadequate for expressing thoughts, and through this, he correlated that the limits of one’s language would in turn define the limits of one’s world. In Wittgenstein’s own words,

“What can be said at all can be said clearly; and whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent.”

~Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is seventy-five pages in length and consists of seven main propositions with a large number of statements further clarifying the initial proposition, amounting to a total of 525 statements. Wittgenstein had a fascination with logic, in that he believed that pure logic would be self-evident and show itself to be true. In light of this, the Tractatus can be described as a series of propositions with no proofs but that are themselves proved by being expressed through language. As stated by Wittgenstein, the work aims to draw a limit to the expression of thoughts, not of the process of thought. The introduction, as written by Bertrand Russell, was not part of the original manuscript. Wittgenstein thought that Russell’s introduction was misleading in that he had misunderstood the point of the Tractatus and had consequentially tainted his work. To ensure an optimal reading experience, readers are suggested to view Wittgenstein’s work in isolation while also taking into consideration their own thoughts and philosophy of the world. By practicing this, one verifies what has already been thought of, and with each succeeding proposition, one will realize the limit that they are subjected to, which is themselves. In trying to express this limit or give it a lingual form, one either fails or utters complete nonsense, becoming aware that they themselves are the limits of their respective world. Each proposition and resultant points of clarifications made through a series of statements will be thoroughly deconstructed and interpreted in the following text.

The World is Everything that is the Case

The first proposition is arguably the most simple and easy to understand. Succinctly put, “The world is everything that is the case.” What is the case is the existence of a combination of various ‘states of affairs’ that possess a ‘sense’. A sense is one that corresponds to a truth value. A state of affairs that possesses a sense is referred to as a positive fact. These positive facts reside in a ‘logical space’, which is an allusion to describe reality. That which is not the case are the states of affairs that are currently false, referred to as negative facts. These do not make up the logical space but can be expressed through language, therefore they exist. Both positive and negative facts exist independently of each other. Thereafter, this logical space of existing states of affairs is in turn, made up of interlinking ‘objects’ or things that make up the world. That which is not the case are objects that do not correlate to an existing state of affairs; therefore, they do not form a part of the world. This posits that ontological questions can only be answered by listing the facts, not the things. For example, the ontological question pertaining to the existence of goblins can only be falsified on the basis that they only occur in fiction and have not been observed in reality. The very concept of a ‘goblin’ is a thing, not a fact. What is a fact is the existing states of affairs surrounding the existence of a goblin, from which we can derive that goblins do not exist in logical space.

What is the Case, the Fact, is the Existence of Atomic Facts

In order to delve deep into this proposition, we must first describe the logical atomism employed by Wittgenstein and map the ontology of these logical entities. As already established, the logical space consists of a combination of states of affairs, otherwise known as ‘atomic facts’. These states of affairs can be true or false, alluding to the previous mention of positive and negative facts. These states of affairs can be thought of as the simplest facts. It should be noted that the truth or falsity of an atomic fact does not have a bearing on the nature of other atomic facts. These atomic facts, in turn, are made up of interlinking objects. These objects are independent and irreducible, often termed as the ‘substance’ or essence of the world. Objects manifest as constituents of a ‘logical form’, common examples include time, space, the visible spectrum of light, numbers, and color. They are simply a set of possibilities that exist within a logical form and define themselves when used within an appropriate context, the context being an atomic fact. These objects consist of internal and external properties. The internal properties confer the logical form and nature of the object. It also determines how it combines with other objects. These logical forms form the substance of the world and are necessary; therefore, other worlds without these logical forms cannot exist. For example, in a different world, the color of the sky can be red, but no world can exist without the logical form of ‘color’. The existence of this substance in the world can be confirmed by observing that logical forms cannot be contingent. By entertaining the fact that logical forms can be contingent, the proposition that “green is a color”, and that “the grass is green”, cannot be correlated as the logical form ‘color’ as color is contingent and has the possibility to exist in other logical forms such as a number. This logic can be elucidated by changing the sentence to “the grass is six’ which does not mean anything and is reduced to ‘nonsense’. Therefore, the sentence “the grass is green” cannot exist independently, which does not make logical sense as facts are required to exist on their own. The external properties of an object are entirely contingent on what is true in the context of a state of affairs. The internal properties of an object do not determine what is the case, as what can be the case exists in multiple forms constrained within a logical form, such as the color blue and white, which exist as simply ‘color’. Instead, what is the case can be determined by analyzing the external properties of an object, which tells us what is the case in the world.

Defining an object is quite hard, as asking this question is tantamount to asking, “What is commonly shared by everything?” Wittgenstein answers this question by stating that all objects occur in a common logical form that allows them to exist within a state of affairs. We can conclude from this that objects are the simplest forms of being, and that the one thing commonly shared among all objects is that something can be said about them. Objects within a state of affairs are able to combine with each other, similar to the linking of chains, as objects are the constituents of a common logical form. Now that the definition of an object is simpler to grasp, it is much easier to define the nature of a positive and negative fact. It should be noted that the world is the totality of positive facts that hold to be true in a logical space.

The Logical Picture of the Facts is the Thought

This proposition primarily deals with human expression as transmitted through language. Wittgenstein focuses more on the form in which language and constituent forms of expression exist rather than the epistemological or psychological analysis that Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege are known to undertake. Wittgenstein states that thoughts manifest in a logical form and that it is completely impossible for a person to have an illogical thought. He calls such thoughts, without sense, nonsense. These are thoughts that possess objects that do not combine. For example, the thought “the grass is green” makes much more sense than to think, “the grass is six.” Wittgenstein explains the correlation between logical forms and thoughts through ‘picture theory’, which states that propositions are logical pictures of facts. Here, we must properly define what a proposition is in the context of Wittgenstein’s work. A proposition can be thought of as the representation of a fact. Conventionally, it is most often thought of as the meaning behind a sentence. Let us say the sentence “I like oranges” is being said in seven different languages. The very essence and meaning behind what is being conveyed through each language can be thought of as a proposition, but what is uttered is a sentence. Wittgenstein referred to sentences as ‘propositional signs’, which are the manifestation of a proposition in the form of language. Anything that exists in logical space can be thought of as a logical picture in our mind. What we think of as facts are most often represented as pictures in our minds. It is nigh impossible to entertain a thought that is not a positive or negative fact that exists as a string of objects sharing a common logical form. In order to understand this concept, Wittgenstein explains that it is possible to conceive of a scenario that violates the laws of physics but not the laws of geometry. Let us take the example of a model car. It is easy to represent, within the limitations of this form, the car floating in mid-air. However, it is impossible to make the car exist in a state of superposition, i.e., in two places at once. The same example of this logical form can be applied to having thoughts as a series of logical pictures, representing a viable fact. For every positive or negative fact, there is only one picture that is able to represent it. Following this line of thought, the third proposition states that for every conceivable logical picture, there is only one corresponding thought. This thought is contingent in that it can represent a positive or negative fact as it shares the same logical form of logical pictures. Therefore, it is evident that illogical thoughts cannot be perceived as they do not follow the laws of logic. Similar to how length is a point of commonality between a ruler and an object it is trying to measure, since a logical picture and a fact share a common logical form, we can visualize a logical picture in our minds as the constituents of a fact. The logical form is how logical pictures are represented in our minds, but this logical form cannot be depicted by words; instead, it shows itself in the real world. Therefore, it is important to make the distinction that facts are what can be said, while the logical form is something that can only be shown. Finally, Wittgenstein states that thoughts can be represented as propositions. Similar to a logical picture, propositions share a common logical form behind them and can be used to express a possible state of affairs. The sentence “George was a peace-loving pacifist" is logical in contrast to the sentence “was peace-loving pacifist George a” since it has a logical form and there is internal coherence. In conclusion, sentences share the same logical picture as propositions, which share the same logical picture as thoughts, which in turn share the same logical picture as facts.

The third proposition also extensively covers the representation of propositions in the form of logical calculus. Wittgenstein states the following to make such a case,

“We must not say, the complex sign ‘aRb’ says ‘a stands in relation R to b’; but we must say, ‘that ‘a’ stands in a certain relation to ‘b’ says that aRb.”

~Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, statement 3.1432

It has already been established that facts can be said, and the corresponding logical form can only be shown. Following this trail of thought, one can say that the relationship between variable elements of a proposition can only be shown as a logical form. Wittgenstein uses this conclusion in order to solve Russell’s paradox, which states that a set of all sets that cannot contain itself cannot exist since such a set contradicts itself. To explain in a simple fashion, the logical form of a set and the logical form of a set that cannot contain itself are not the same; therefore, Wittgenstein states that there is no paradox to begin with. To further illustrate this point, we need to dig deeper into Wittgenstein’s viewpoint on language. He begins by stating that the sense of a proposition is intrinsic to itself and is meaningless without proper context. Reading a dictionary today will give us a catalogue of words along with their meaning. However, the meaning of the word in question can only be elucidated by using it in a sentence. Wittgenstein concludes that a word, name, or sign can only show its intrinsic meaning when used in a proposition. If words were to show meaning in isolated usage, there would not be any confusion in deciphering their meaning in a sentence. Language is flawed by the fact that it is illogical in nature, and any attempt at expression without the application of logic leads to uttering nonsense. This is due to the fact that certain words can have differing meanings based on the context in which they are used. Since meanings can differ depending on the use case, the usage of a word itself can be thought of as a logical form. Applying the same logic to set theory and functions, Wittgenstein managed to solve Russell’s paradox by disproving its existence in the first place, stating that a set that makes a statement about itself follows a different logical form relative to a normal set. This proposition was not made as an effort to solve Russell’s paradox but rather to only establish the point that the sense of a proposition is ultimately intrinsic to itself and that the meaning of a name or a word is seen in its usage.

The Thought is the Significant Proposition:

Here, Wittgenstein explains that the totality of all true propositions contains the limits of what can be expressed through language. Although natural language uses a logical structure, its application in human expression is flawed due to its inability to rarely, if ever show its logical form, thereby creating confusion. The reason we are able to understand speech is due to the fact that there is a commonality between logical form and stating propositions. Although not properly covered in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein says that as long as the logical form of a language properly shows itself, there need not be any rules for its interpretation as the rules would also, in effect, show themselves as long as the logical form is properly conveyed. In later years, he would go on to further delve into this concept of creating rules for the interpretation of language in future works and correspondence, particularly in his posthumous work, ‘Philosophical Investigations.’ Wittgenstein makes it clear that propositions are not reliant upon their truth function and that logical inferences can be made regardless of whether or not the proposition is true, purely because it can be expressed through language. Wittgenstein’s penultimate claim that logical constants such as ‘is’, ‘and’, and ‘not’, and by extension, the logic of facts cannot be accurately represented as propositions is made clear under proposition 4.0312. This claim can be further used to propose that the relationship between propositions and logical forms can only be shown and not expressed through language. Wittgenstein makes the point that deriving logical inferences and relations by using language as a means of expression is meaningless, as the logic of the world can only be shown, not said. The duty of the natural sciences, as Wittgenstein explains, is to make propositions about what is the case in the world, regardless of whether they are true or false. In contrast, Wittgenstein describes philosophy as an activity that further shows and clarifies the propositions that the natural sciences raise about what can be said. Through such clarification, philosophy will aim to describe what cannot be said of the world by clarifying various propositions that are inadequately conveyed through the usage of language. In summary, the primary aim of philosophy is to show what can and cannot be said about the world by establishing a clear set of logical propositions. It has been made clear that propositions encompass the whole of reality, but they are by themselves not able to express the logical form of reality. Instead, they are just statements that describe what is and is not the case in the world. Propositions are only able to describe that which is external to them; therefore, to describe logical form, one would need to do so from a perspective that exists outside of reality or logical space. This is an impossible task as propositions can only exist in logical form by sharing the reality that they are trying to depict.

In addition to Russell’s paradox, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is also a response to Frege’s work on making a logical distinction between an object and a concept. Wittgenstein makes an additional distinction between a ‘formal concept’ and a ‘concept proper’. A formal concept is one that references a logical form that can only be shown to occur in the context of a proposition, and as such, cannot be expressed as a variable function. A concept proper is one that can be spoken about and can be represented as a variable function. Take for example, the statements “X is a number” and “X is a cat.” To Wittgenstein, to say that “X is a number” would be tantamount to saying nonsense, as the proposition does not represent any real-life situation. To assume to know what a person means when they say that “X is a number” is to be led astray by the common structure of a language. It would be wise to observe that the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus has employed the usage of many formal concepts in order to lay an ontological and linguistic basis for describing the nature of logic, so naturally one must conclude that the work contradicts itself, right? Wittgenstein indirectly hints at this point near the end of his work and the reader is expected to realize the reference when it shows.

Propositions are Truth-functions of Elementary Propositions

Elementary propositions can be defined as the basic and fundamental parts of a proposition. For example, the proposition “David is good natured and wise” (a.b) can be divided into two elementary propositions: “David is good natured” represented as ‘a’, and “David is wise”, represented as ‘b’. The above elementary propositions which exist independently of each other, can be expressed as a whole proposition by representing them as a.b. The truth or falsity of such elementary propositions does not depend on external factors. All logical propositions can be expressed as a ‘truth table’ and can be denoted as either a tautology, a state of always being true, or a contradiction, a state of always being false. Wittgenstein made the claim that false propositions that are often reduced to contradictions can be thought of as logical in nature because they can be expressed through language and do not exist in actuality. This was in stark contrast to contemporaries such as Frege and Russell who often held that contradictions are illogical in nature. Wittgenstein thought that such a limitation was arbitrary in nature and held that propositions that cannot be reduced to a logical notation are more akin to being nonsense. Wittgenstein also claims that the theory of probability is only a procedure based on psychological grounds and that all degrees of probability are not based on reality. Instead, he says that propositions are only either true or false. By making various deductions through the usage of truth tables and the critical analysis of logical inferences, constants, and axioms, Wittgenstein further assaults the ideas of Frege and Russell by stating that such inferences and relations only further complicate logic by giving it a needless metaphysical background. Instead, Wittgenstein prefers that logic, in its purest form, will explain and unravel itself. He clearly states that such procedures serve to say that which can only be shown. He equates all logical propositions as tautologies that ultimately convey nothing. He insists that logic does not need to follow any rules, that whatever is illogical cannot even be represented as a proposition, and by extension, such non-existent propositions cannot break the so-called rules of logic. He dismisses the very notion of using the ‘=’ sign, citing that expressions such as ‘p=q’ are meaningless since to say that two identical things that share different names are identical in the first place is nonsense, as they would not be two different things to begin with. He goes on to say that the expression ‘p=p’ is also redundant since it effectively conveys nothing.

Halfway through the fifth proposition, there is a clear shift from logical discussions to a more metaphysical one, one that concerns the soul. Assume a person named ‘X’ to say sentences that include a proposition ‘p’ such that “X believes that p” and “X says that p.” For X to think that such is the case, the proposition manifests in the form of language, and the correlation occurs between the proposition and what it pictures, not as a result of the consciousness of the person X. Wittgenstein states that a human soul in which thoughts and beliefs reside does not exist in the real world, so instead he represents the human soul as a two-dimensional cube that projects on either side. He states that the soul is a composite and can have a form in this manner. He also suggests that this composite soul is made up of numerous beliefs such that it entertains. In the same way that such a two-dimensional cube does not exist in the real world and merely feigns the appearance of one, so too does the composite of thoughts and beliefs that the soul entertains appear as a soul to us from the outside. Because the soul is a composite, it cannot stand as a unified ‘X’ in a proposition. In the case of beliefs, he states that we should not analyze the proposition existing between the belief and a unified consciousness X. Rather, the proposition manifests between the belief as it is being expressed and as it appears in the composite consciousness. Due to this, we cannot learn a priori what objects and elementary propositions exist in the first place. Logic is prior to the experience, but it is not prior to the fact of the experience itself. He goes on to explain that logic is a tool that helps us study a variety of elementary propositions and objects. Wittgenstein finally goes on to state,

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

~Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, statement 5.6

The limits of language are the totality of elementary propositions, and the limits of the world are determined by the totality of facts. There is a directly proportional correspondence between elementary propositions and facts; therefore, we cannot say what lies outside the world, meaning that we cannot say or think of anything that is illogical. It is natural to conclude that we cannot say or perceive anything that lies outside this limit. Wittgenstein goes on to state that there is some truth to solipsism, but that this truth is only the case according to a certain limit. This is because we only know of the existence of objects and other people because we are conscious of them. The expression of what a solipsist says is true, but since they put into language what can only be shown, they begin to speak nonsense. Going by this line of logic, they can conclude that they themselves are the limit of their own world, which naturally translates to them being the only existence to exist. The solipsist goes on to ponder, “What is ‘I’?” as they cannot find what ‘I’ is in their own experience or consciousness. There are no objects or elementary propositions that correspond to the self; therefore, there are no propositions with a sense relating to it. An analogy can be made that one is born without visualizing his own eye, but the existence of a visual field presupposes the existence of an eye to see it. In the same way, the ‘self’ is not something a person can encounter within their own experience. The idea of a self is not something that appears in the world, nor is it something that can be talked about. It is rather a limit to the world, which is nothing more than the ideas, thoughts, and beliefs that constitute it. This is what can only be described as ‘the barest form of oneself’. Such a limit is insubstantial in that it does not presuppose that there is a higher sense of self that one can access. From a solipsist’s perspective, this idea of the self cannot be expressed in language since the logical form of the world, language and logic cannot be said, and can only be shown. The self is the same as the world, language, and logic. It is the limit to all that can be and what is possible. Only propositions that express the truth functions of elementary propositions can possess a sense.

The General Form of Truth-function is: [p, ξ, N(ξ)]

Wittgenstein proposes the general form of a truth function. From proposition 5, he concludes that all logical operations are repeated negations. From this, he concluded that all logical propositions are one of a series of negations on elementary propositions. He represents [p, ξ, N(ξ)] as the general form of a truth function. Readers are suggested to study this proposition in its rawest form by reading the original work in order to appreciate the intense exercise of mathematics that goes along with it. In contrast to Immanuel Kant, who proposed that mathematics was based solely on intuition, Frege proposed that mathematics was a logical system that was much more grounded and reliant on logical axioms. Wittgenstein similarly makes a claim that mathematics is a logical method. The difference in his view being that he argued numbers were not logical objects that were derived from logical forms. He claimed that numbers were an exponent of an operation. In response, several critics such as Bertrand Russell and Frank P. Ramsey have rightly pointed out that Wittgenstein’s description of equations as the propositions of mathematics is inherently flawed, as mathematics also contains inequalities in addition to equations. This critique came to light after the fact, and so it remains unaddressed in this work. Wittgenstein describes logic as a framework that does not come with its own set of propositions that have a sense and instead offers a place for substantial propositions to fit into. This framework exists to build a world diversified in propositions. The world and this logical framework share points of contact where a common logical form exists. However, there is no similar analogue for the content of the world. According to Wittgenstein, logic is a tool that is not necessary to be used in an ideal world where language is sufficient. When language is insufficient, these tools of logic and philosophy automatically come into play when nonsense is spoken. As mentioned previously, all logical propositions are tautologies that convey nothing and are ultimately meaningless. Any attempt to give content to them is a fruitless endeavor as they are the case, which in turn forms an overarching framework within which is contained both language and the world. All logical propositions which are themselves tautologies are self-evident. Wittgenstein additionally posits that laws that are used to describe natural phenomena are not themselves things that have been discovered experimentally. By positing such a statement, he is not opposed to the usage of the scientific method but is instead skeptical of the power of science to give us answers to fundamental philosophical questions. He further deduces that the world has no logical connection to human will or any sort of natural phenomena, what is possible or necessary is a priori to such a fact and only comes into existence after experience. The logical inference is visible by making the statement,

“As there is only a logical necessity, so there is only a logical impossibility.”

~Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, statement 6.375

Whereof One Cannot Speak, thereof One Must be Silent

The final proposition is quite arguably one that is most open to interpretation. Most inferences from the previous propositions are made here, so the reader is encouraged to go and read the second half of the preceding proposition to produce their own interpretation. Wittgenstein proposes that statements made in regard to values such as ethics and aesthetics can only have true value when they exist in a higher sense of reality, that is, outside the logical space. It has already been deduced that such a thing is a logical impossibility. A person by extension, can only hope to alter the limits of their own world through their natural will. Such an alteration will lead to the experience of a different world, one that is as enigmatic as the previous one. As Wittgenstein states,

“The world of the happy is quite another than that of the unhappy.”

~Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, statement 6.43

He further states that death is not something a living person can experience, as death is an event that precedes the cessation of the world. Leading a timeless life is akin to living life eternally in the present. Living with the hope that one’s life does not end after death is not a guarantee of such a belief, as the ‘riddle’ still remains unsolved. The solution to this riddle, Wittgenstein hints, is that it exists outside of our reality, thereby condemning us to live an eternal life without ever having access to it. The state of the world and its limits remain completely indifferent to the existence of any higher being that exists outside the logical space. This higher being, commonly viewed as 'God', cannot show itself to the world, as it transcends the limits of reality and therefore is illogical. What is truly mystical is not the state of the current world and its limits, but the very fact of its existence to start with. The feeling that one derives from looking at the world as a limited whole is a mystical one. This viewpoint is referred to as ‘sub specie aeterni’, a term borrowed from Baruch Spinoza meaning ‘under the sign of infinity.’ If the answer to the riddle cannot be expressed, so too does the riddle itself not exist in the first place. The solution to this riddle expresses itself by manifesting in its own vanishment; there is no riddle in the first place. What is inexpressible can only show itself, that within itself is mystical in nature. For clarification, the word ‘mystical’ here refers to unsubstantiated beliefs that cannot be expressed in language but can only be shown. Wittgenstein states that the right method of performing philosophy is to say nothing except what can be said through making propositions by utilizing natural sciences, something that has nothing to do with philosophy in the first place. After this, if anyone dared to propose the existence of the metaphysical, the quintessential duty of a philosopher would be to show him that the signs he makes carry no meaning within the limits of the world. Naturally, the other person will be left feeling unsatisfied, as they will feel as if philosophy is not being performed, but this remains the only valid method through which philosophy can be properly executed. Wittgenstein concludes by saying that the reader who has perfectly understood him has also understood that all of his propositions are senseless, and in doing so has also shown the reader something that cannot be expressed purely through language. Once they have looked beyond the propositions, they will finally conclude,

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

~Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, proposition 7

Conclusion and Interpretation

"This work is supposed to be a mirror representation of what the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is trying to convey. In effect, if you have thoroughly read and understood what this body of text is trying to show, you have also reached the same conclusion as one would if they read the Tractatus proper. The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is an almost life-changing build-up to what can be said, namely that nothing can be said. As Wittgenstein points out, once you look beyond the propositions and try to comprehend what he is trying to show and not say, you have gained the ability to momentarily experience the world from the sub specie aeterni. You are able to perceive the world as a limited whole and also realize that no metaphysical claims can be made and that all philosophical problems have been solved. Consequently, you will also realize how little has been solved by doing so. This might be a troubling realization to some as it would mean that not only philosophy, but even ethical claims have absolutely no ground. One can only ‘be ethical’ according to one’s beliefs. From the viewpoint of the sub specie aeterni, an individual is free to do what they will as their beliefs dictate. This individual can start over and make metaphysical claims that mean nothing or pretend to have an ethical ground to stand on. From such a viewpoint, one truly realizes what matters to them and so sees to it that they pursue that which makes them happy. This pursuit of happiness is indifferent to the happiness of others as it might positively or negatively affect other people, but such restrictions as ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ manifest as a limit to the subjects themselves. As is the case, not much changes after realizing what the Tractatus is trying to convey, except for an overwhelming realization that there is nothing to be said. It is quite ironic to realize that what can be gathered from the above text is the realization that it ultimately conveys nothing. To the one who holds such a realization, only they know that this realization is such that it holds immense value. The only thing one can do is to “live happily” as Wittgenstein states in his Notebooks (1914-1916), such is the case regardless of the fact whether or not it is stated. It is of importance to note that there are several interpretations of Wittgenstein’s work, most of which fail to see what Wittgenstein is trying to show. A primary example being the author of the introduction to the Tractatus, Bertrand Russell.

In a world of multiple interpretations, one will try to find the interpretation that makes the most sense to them. In fact, I find it entertaining to read such interpretations since none of them will make sense to anyone else in the first place. The search for an optimal interpretation is analogous to music and lyrical design. Most people would agree that there must be an optimal language to express the lyrics of a certain piece of music. There is an optimal language that one could make use of to make their song maximally rhyme or use effective metaphors to show others what they are trying to say. Only those who are fluent in every language can deduce the most optimal way to convey and consume a piece of music. Does that invalidate the happiness of a person who enjoys music for what it is in silence? That question can be applied to the interpretation of any work. To that end, I say that the most optimized version of an expression of language is the one that makes the most sense to a person at that particular point in time. The difference between words uttered and music expressed is akin to the difference between the World and God. One might ask, "Well, how do I make sense of your interpretation?" To that I say, look beyond the words that I have written, and you shall remain silent. The interpretation I shall posit afterwards is wrong. The 'right' interpretation of the Tractatus lies outside of the World. The expression of the Tractatus also does not belong to Wittgenstein, similar to how the words of this article do not belong to me. Both works belong to this World irrespective of the subject that's responsible for expressing their work. There is no ideology expressed here. What is expressed here is the bare logical framework, which is devoid of any propositions. That is, the framework of the sense. One is free to fill it with whatever nonsense they entertain. God is dead, so are the natural sciences and philosophy. Sisyphus is happy, and philosophy is a rehearsal for death. Likewise, God is not dead, nor are the natural sciences or philosophy. Sisyphus is not happy, and philosophy is not a rehearsal for death.

"Form is no different from emptiness, and emptiness is no different from form. Form itself is emptiness, and emptiness itself is form."

~Heart Sutra, Mahāyāna Buddhism.

In lieu of this, I shall present my interpretation of this work as it shows itself within the context of my own world and its limits through the language which I express it as.

Firstly, I need to hold that to say nothing and to also say everything that needs to be said at the same instance is truly the highest achievement of the Tractatus. One of the reasons why I tried to deconstruct the Tractatus is so that when someone in the future asks me what I mean when I start quoting Wittgenstein, I can redirect them to this body of text. The language presented here serves the same purpose as to what Wittgenstein used the Tractatus for: to show other people what he means when he says what he says. The language expressed here is the closest I can possibly come at this point in time to communicating my interpretation of Wittgenstein’s work.

The conclusion of the Tractatus is that the logical picture of every proposition that one holds as a thought about the world manifests in the illogical, i.e. outside the sub specie aeterni, i.e. outside the limits of one’s world. Thus, such a proposition negates and shows itself to be nonsense when expressed as language in the logical space. One can only express silence thereof. The definitions of a logical picture, proposition, the world, sub specie aeterni, limits of one’s world, nonsense, logical space, and subsequent relevant terms can be inferred from the Tractatus.

Philosophical problems can only exist when a proposition is devised by a particular natural science, such as Biology. When such a proposition is made, philosophy manifests and negates it, rendering it meaningless and the expression of which can be thought of nonsense.

It is not that nothing exists, but the something that does exist cannot be expressed, and if it cannot be expressed, that something may as well not exist, leaving nothing.

The conclusion of the Tractatus has always been the case and has merely been expressed as such by Ludwig Wittgenstein through his application of logic, mathematics, linguistics, and philosophy. I find that this point cannot be made even clearer, so I shall repeat it. The conclusion of the Tractatus has always existed, independent of Wittgenstein’s attempt to express it.

If one cannot comprehend the conclusion of the Tractatus, then such is the case, as what is being expressed here is nonsense that is subject to the limits of one’s world. An attempt can be made from one’s side to comprehend the Tractatus, but by doing so, one will reach the same conclusion, namely that what is being conveyed here is by itself nonsense.

From my perspective, the Tractatus represents what I have always held to be the case ever since I could conceive of rational thought. Such a realization, I held to be true but always found myself dumfounded on how to give it form. The philosophy that Wittgenstein expresses here has been one which I had followed even before I knew that there existed an expression for it. This philosophy as I knew it, was self-evident. I also make the case that such holds true for most, if not all the people who experience their respective limits of the world.

I draw a number of substantial inferences from this work, such as rationalizing the concept of death. It is natural for me to say that I no longer fear death. I only fear death as much as I fear falling down a flight of stairs, which is to say that I fear only the physical process of death itself, not the cessation of my world.

The word ‘happiness’ is quite inadequate to describe the state of ‘being happy’. What I can say to be the case is that one exists in one’s maximum state of being happy in any such case, as it cannot be shown otherwise.

Does this mean that I have attained an invulnerability to suffering? The answer to this question and a great number of substantial propositions that I derive from the Tractatus and the World will not be conveyed here. The nature of such propositions that I wish to convey here themselves does not want to be uttered here. The consequences of the current state of the World will necessitate a work that clarifies the World as it exists external to itself. Such a work will reveal itself in time. To those who wait in non-existent anticipation and to those in the future, I leave the following words: ~“The World of The Child is Eternal.”

A natural question arises, “What comes next?” The only thing that is left for a person to do is to act in a way that makes ‘sense’ to them within the limits of their own world. What I have just said is completely meaningless because the person in question is already doing that. There was no need to express this through language in the first place. The only way to act otherwise to what I have said is to transcend the logical space and act in a way that can only be described as ‘illogical’, which is impossible. In effect, nothing is being said here.

Now that everything that I have needed to say has been said, which is effectively nothing, I can finally do what I want, which is something that I have already been doing my entire life that cannot be shown otherwise.

Similar to Wittgenstein, I hold hereby that whatever I can say about the world has been said in this work. Namely, that nothing can be said. The Tractatus and the expression for the philosophy it conveys speaks for itself, therefore I have nothing more to say about it."

To whomsoever reads my words, to them I say that nothing has changed by doing so. I leave the readers with a couple of quotes from Wittgenstein,

“I keep on coming back to this! Simply the happy life is good, the unhappy bad. And if I now ask myself: But why should I live happily, then this of itself seems to me to be a tautological question; the happy life seems to be justified, of itself, it seems that it is the only right life.”

“It seems one can’t say anything more than: Live happily!”

~Ludwig Wittgenstein, Notebooks 1914-1916

written and researched by: Tawfeeq Ahmed

Cited Literature and Further Reading

Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius by Ray Monk

Notebooks 1914-1916 by Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by G.E.M. Anscombe

On Denoting by Bertrand Russell

Philosophical Investigations by Ludwig Wittgenstein

The Foundations of Arithmetic by Gottlob Frege

The Principles of Mathematics by Bertrand Russell

The World as Will and Representation by Arthur Schopenhauer

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus by Ludwig Wittgenstein

Tractatus Theologico-Polticus by Baruch Spinoza

Wittgenstein: A Religious Point of View by Norman Malcolm

Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911–1951 by Brian McGuinness

*If the current work features a part or segment(including image used) of your intellectual property, which has or has not been referenced and you deem its use in the article as inappropriate, illegal or unfitting, you can contact us through LinkedIn message.