di Laura Violet Rimola

In the Civic Archaeological Museum of Sesto Calende, right in the center of the main hall, a rich grave goods dating back to the 1977th century BC is exhibited, occasionally discovered in March XNUMX in the Mulini Bellaria area in Sesto Calende, a few steps from the banks of the Ticino.

The small necropolis to which it belonged was arranged along the terrace of the river and included burials of two distinct phases, the first referable to the period between the end of the 2th and the beginning of the XNUMXth century BC (Golasecca I AXNUMX) and the second to last quarter of the XNUMXth to the beginning of the XNUMXth century BC (Golasecca II B)[1]. The phase to which the equipment in question belongs is the second.

Observing the showcase in which the finds are arranged, you immediately notice the plate with the brief explanation:

"Princely tomb belonging to a female person. Although partially plundered in ancient times, it has preserved finds of great value, witnesses of the cultural and economic exchanges of the Culture of Golasecca."

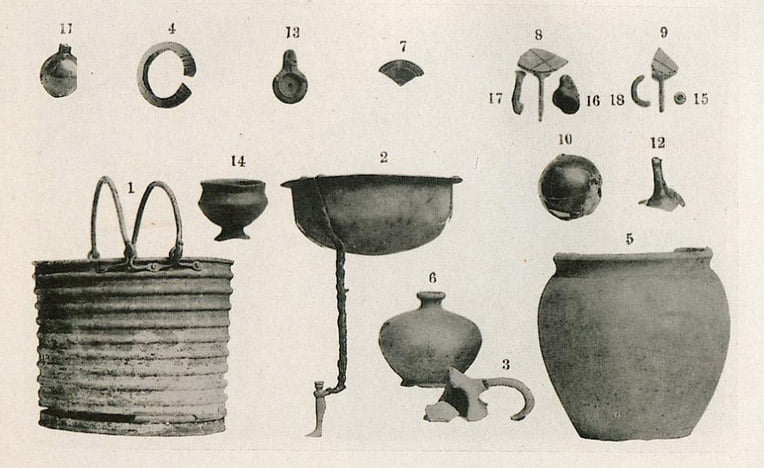

The objects on display are therefore only a part of the original equipment[2], and include several ceramic cups, a precious amber whorl, globular amber beads, amber pendants with a stylized anthropomorphic shape, a fossil wood bracelet, a long and elaborate pectoral composed of thirty chains each ending with a small bronze pendant in the shape of a drop, and some elements of women's clothing, such as brooches and the rectangular clasp of a leather belt. The most precious finds, as well as being significant for understanding who the grave goods belonged to, however are a bronze situla decorated with embossing and a bronze basin supported by an iron tripod with anthropomorphic feet, both linked to the ritual sphere, in particular the basin , which was used to carry out divination practices.

These two finds therefore allow us to classify the woman buried as a priestess, who lived on the banks of the Ticino, near present-day Sesto Calende, during the mid-sixth century BC

All of the artifacts in the outfit had been hers, and reflect the role as well as the appearance she had had during her lifetime. In fact, she can be imagined dressed in a long, straight dress – in the style of the time – in soft fabric, fastened at the waist by a leather belt with a rectangular buckle. She had brooches on her shoulders, her neck adorned with pendants and amber beads, and a showy wooden bracelet on her arm. It is probable that the large breastplate with chains was not worn by her every day, but only during certain rituals, when she also used the situla and the precious tripod, in whose basin she looked out to divine, her face reflected on the surface of the water .

Even the spindle whorl must have had a sacred purpose for her, as it was made entirely of amber, unlike those of ordinary women, which were usually made of ceramic. It is therefore possible that it too was part of the ritual instruments associated with the cult that the woman practiced and represented in the eyes of her people.

Her role must have been highly respected, and she was much loved, just think that her trousseau, despite being looted in large part by grave robbers, remains the richest in the museum - even richer than all the men's trousseau. This suggests that her position within the community was primary and extremely important.

Although we do not know how he lived and what his priestly duties were, as well as the rituals he conducted, it is still possible to draw some clues by observing his sacred instruments more closely, as well as the environment in which he spent his life. Inside the cups collected from his tomb, the presence of food offerings was found, and despite the acidity of the soil it was possible to identify some remains of bird bones, and traces of a liquid that could be milk[3]. They had been offered to the priestess milk and birds, perhaps to feed, although it is possible that the birds filled the role of psychopomps and that they had been joined to accompany her soul during the otherworldly journey.

Furthermore, analyzing the corded shoulder situla, characteristic of the Golasecca culture, it can be seen that the handle ends on both sides with an S-shaped motif that gives shape to two stylized ornithomorphic heads. It is therefore conceivable that the priestess was linked to birds and their symbology. He lived on the banks washed by the river with his people, a few steps from Lake Maggiore, and perhaps part of his cults were aimed at divinities of water, fertile land and air, direct heirs of the Neolithic Bird Goddess who embodied fertility, nourishment , abundance, luck, and manifested itself in the form of aquatic birds such as swans, ducks, herons, but also coots and grebes. The same birds that still swim quietly on the waters of the Ticino, right in front of the town of Sesto Calende.

But it wasn't just the river and the lake that were part of the sacred landscape where the mysterious priestess lived. In fact, the giant rises very close to her burial Sass from Preja Buja, a complex of green serpentine erratic boulders where pagan rituals have taken place since the dawn of time. The largest boulder displays a characteristic hen shape – hence the name golden hen or golden pita – with a ram's head, while the horizontal stone placed at its feet has various incisions in the form of rings, seats, numerous cup marks, and was used as an altar.

It is undeniable that the priestess of Sesto Calende was well acquainted with the megalith, and habitually frequented it, or that she practiced some of her rites right in front of it, using the large cupped stone as an altar on which it is probable she left offerings of food and liquids such as milk, blood, and perhaps some type of fermented beverage produced at the time, such as grape or wild fruit wine and flavored red beer[4]. Furthermore, it is possible that the cup marks were used in healing rituals. The rain that collected inside them absorbed the mineral properties of the stone and was used to heal certain ailments.

It is important to add that on the morning of each vernal equinox the first rays of the sun illuminate the eye of the lithic brooder, engraved in the stone in the shape of a radiant sun. It is therefore possible that one of the celebrations held next to the megalith was dedicated to solar rebirth, or the return of light after the dark and cold winter. And perhaps on these occasions the priestess wore her necklaces and pendants in amber, the solar stone par excellence, which shone golden on her neck and also recalled the rising of the new sun.

Finally, it should be remembered that traditionally the erratic boulder has always been associated with the Great Mother, and still in relatively recent times, women who wanted to have children, or an easy birth, went there and touched it with their bellies - or sat on the seats engraved on the altar. It is therefore probable that part of the rites practiced at the Preja Buja were dedicated to the divine feminine and her harmonious influence on the female body[5].

Il Sass from Preja Buja it therefore had an essential part in the life of our ancient woman, but it was not the only megalithic complex she knew, and perhaps frequented. Continuing along the path on the edge of which stands the large stone hen, reaching the top of the hill and entering the thick wood, another symbol of the ancient cults of the area can be found among the dense vegetation, namely a small dolmen. Under its stones is hidden a burial chamber, from which a cinerary urn was stolen in the 60s, and although there is no certainty about it, it can be assumed that also in this case the urn was accompanied by a kit.

Although this dolmen is almost completely unknown today, it is likely that it was well known at the time our priestess lived, who perhaps went there to perform some of her rituals in harmony with nature, or simply to celebrate the memory of who was buried there: probably a woman or a man who enjoyed particular respect and honor among the ancient inhabitants of the place.

On the basis of the finds found and the characteristics of the territory to which they belong, it is therefore possible to mention a portrait of the mysterious priestess of Sesto Calende, who undoubtedly must have been a prophetess, a diviner who knew see and read signs and omens in the waters of the basin, a spinner who used the amber spindle for cultic reasons, a sacred woman who wore the distinctive ornaments that accompanied her in death on a daily basis and/or during certain rituals. She was a custodian of the cultic tradition of her people, a living embodiment of the divine who spiritually guided her community, a bride of the earth, the sun and the river, perhaps intimately linked to waterfowl and their volo, and practiced ancient rites in the presence of the Preja Buja.

Unfortunately, among the objects plundered by grave robbers from his funerary equipment there is also his urn. This large decorated ceramic cinerary vase which contained his remains has never been found, and if it has not been lost it could be part of some illicit private collection.

The priestly trousseau, or at least what's left of it, has been separated from its rightful owner, and she's gone. But her story has remained imprinted in her objects, in the places she frequented, in the care with which she was buried. And thanks to them, after millennia, this ancient woman can be known and remembered again, and her memory honored as it once was.

The priestesses of the tripod of Golasecca

As we have seen, the tripod tomb of Sesto Calende offers enough clues to try to know the one who had been buried there. However, it must be said that it is not the only burial with these characteristics, since other very similar ones have been found, both in the same area, in Castelletto Sopra Ticino, and in other development centers of the Golasecca culture, i.e. in the Como area, in the locality Rondineto, and in the Vercelli area, near Pezzana.

These female tombs were all equipped with a tripod with a divinatory basin, therefore they belonged to as many priestesses, and furthermore, with the exception of that of Castelletto which is slightly earlier, they are contemporary. The women who lay there had all lived in the same historical period, performed similar – if not identical – ritual practices using the same sacred instruments and probably celebrated the same cults. It is therefore legitimate to ask whether originally they were part of the same cultic centre, or rather of a sort of archaic priestly sisterhood established in the first development center of the Golasecca culture, and had then separated, following – or leading – the groups that moved towards the Como and Vercelli areas to look for new lands to cultivate and inhabit, or rather to expand and make one's culture flourish in other places.

Not being able to find confirmation of this fascinating hypothesis and having to limit ourselves to considering only what can be demonstrated on the basis of the collected finds, it is nevertheless possible to affirm that in the culture of Golasecca the women, in particular those who, due to the presence in their burials of objects at ritual destination, they performed the role of priestesses, enjoyed a unique importance and consideration. Their trousseau, although often looted and therefore halved, was the richest[6], their objects the most refined and valuable. They were points of reference to which the villagers asked for advice and prophetic answers, and they guided their spiritual life by celebrating the ancient rites at the foot of the ancient stones, immersed in the luxuriant woods, or on the quiet beaches bathed by rivers and lakes. But above all, they were perceived as intermediaries between the human and the divine. Inseparable from the divinity itself, as women, sacred creatures by nature.

APPENDIX – The outfits of the priestesses

Tomb of Sesto Calende – Location Mulini Bellaria – Last quarter of the sixth and beginning of the fifth century BC

The grave goods known as the "tripod tomb", discovered in the locality of Mulini Bellaria in Sesto Calende, include ceramics, ornaments and objects referring to women's clothing, a bronze situla and a tripod. The ceramic objects are composed of “a large cup with a high flared, trumpet-shaped foot with a brimmed rim, four cups with a high foot with a sunburst motif made translucent inside the basin, two with a recessed rim and two with a straight rim; a mug with a truncated cone body, distinct neck and exoverted rim" [7].

The ornaments and objects relating to clothing include a bracelet, or armilla, made of fossil wood, lignite or sapropelite, a rectangular clip in bronze foil which was part of a leather belt entirely covered with small bronze studs; ten brooches, five of which leech shaped; four compound bow fibulae showing traces of coral coating; a large compound bow fibula, which “hung from the pin a 50 cm long pendant, formed by a tubular element of bronze rod wound into a spiral and folded into an inverted U, from the ends of which emerge two pairs of supports that hold thirty long chains, each of which ends with a small pendant drop type bronze”; several amber pearls which were perhaps originally inserted into the fibulae's tongue, an amber whorl and two amber pendants stylized in an anthropomorphic female form, perhaps part of the same necklace" [8].

The bronze situla belongs to the type “with corded shoulder, characteristic of the Golasecca culture throughout the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries BC”; it is characterized by a handle whose ends end in “cwith the characteristic S-fold, which forms the motif of the stylized ornithomorphic head” and is embossed with studs and dots.

The tripod is "consisting of a basin in bronze foil with a slightly careened body, a cap-shaped bottom and an exoverted brim”. Its support is made up of “three iron rods fixed on one side to the rim and wall of the basin and inserted on the other in a cast bronze corbel in the shape of a human leg" [9].

The trousseau is currently in the Civic Museum of Sesto Calende.

Tomb of Castelletto Sopra Ticino – Location Motto della Forca – Half and third quarter of the XNUMXth century BC

Older than the others, and therefore belonging to a priestess who lived a few decades earlier, is the tomb discovered in 1877 in Castelletto Sopra Ticino, in the locality of Motto della Forca - today Motto Falco - which belongs to the chronological phase preceding that of Sesto Calende, ie the period between the middle and the third quarter of the sixth century BC (Golasecca II AB).

The kit consists of: “a funerary urn with a globular biconical body decorated with extra-gloss, a glass with a globular body, distinct neck and extroverted lip, a lidded bowl with a low foot and inverted rim, a small jug with a globular body, two truncated-conical cups with straight lip and low flared trumpet-shaped foot, about forty bronze armlets of the open-headed type, 12 small silver rings and a bronze ring threaded onto the barb of a fibula, perhaps of the ship-shaped type, no longer traceable. The tripod had a bronze plate basin in the shape of a cap with an exoverted brim.” The three support legs, made of iron, were shattered into thirteen fragments and at the time of the discovery they were not considered worthy of note, so they have not been preserved [10]. The kit is kept in the Turin Museum of Antiquities.

Tomb of Pezzana – Location Dosso del Lupo – End of the XNUMXth and beginning of the XNUMXth century BC

The one found in 1889 in the province of Vercelli, in the municipality of Pezzana, and precisely in the locality of Dosso del Lupo, on the right bank of the river Sesia, belongs to the same period as the tomb of Sesto Calende. During the leveling of a mound to level agricultural fields, the fragment of what was discovered to be a tripod emerged. The excavations carried out therefore returned other objects referable to the religious sphere: a cista with cords and bands of dots, in bronze lamina, about 23 cm high, with a diameter of 27 cm, covered with a green patina and equipped with two bronze handles fitted with eyelet; a small vase with handles reduced to pieces, and a mug.

The tripod was composed of a copper plate basin, and of the three feet that were supposed to support the container, only one came to light, made of iron and badly corroded by rust. This shaft shows in the lower part the shape of a human leg, ending in a well worked bronze foot. Next to this, the fragment of another iron support rod, a few centimeters long, was also found. The three legs must have had a total height of about thirty-three centimeters.

Although there are no ornaments or items relating to clothing that can confirm that the tomb belonged to a woman, the entity of the finds found is identical to that of the female grave goods of Sesto Calende, therefore it is probable that also in this case the burial contained the remains of a woman, and therefore of a priestess.

The location of the tomb also proves that the same peoples who inhabited the banks of the Ticino also moved to the Vercelli area, settling on the edge of the Sesia and developing the Golasecca culture in this area. [11].

The kit has been lost for many years, or is kept in private collections of which there is no news.

Tomb of Rondineto (CO) – End of the XNUMXth and beginning of the XNUMXth century BC

Coeval with the two burials of Sesto Calende and Pezzana, it is finally the one located in another great center of development of the Golasecca culture. In Rondineto, in a necropolis not far from the large protohistoric settlement of Como, it was found "a cast bronze leg with the end of an iron rod inserted in the upper part, which is certainly the corbel of a tripod such as those of Pezzana and Sesto Calende" [12]. The trousseau is located in the Paolo Giovio Civic Museums in Como.

Laura Violet Rimola – February 2021

Note:

[1] See Raffaele Carlo de Marinis - "The tomb of the tripod of Sesto Calende" - in Rites and Cults in the Iron Age – Conferences June 1998 – pag. 18;

[2] The tomb had already been plundered in the past: “the cover plate had been removed, in the north-western part of the burial chamber no grave goods were found, the cinerary urn and the so-called accessory glass, typical elements and constantly present in the tombs of the Ticino facies of the Golasecca culture, they were absent. (…) The collapse of a slab and numerous pebbles belonging to the original overlay allowed the preservation of a part of the grave goods, even if seriously damaged due to the crushing suffered.” (See Raffaele Carlo de Marinis – op. cit. – pp. 17-18);

[3] See Raffaele Carlo de Marinis, on. cit., p. 18-19, 21;

[4] In this regard, it is worth noting an important discovery that recently took place in Pombia, in the province of Novara, where a burial with a cinerary urn and an accessory glass from 560 BC was found, in which traces of a drink obtained from the fermentation of cereals were found. and flavored with herbs and hops: the first evidence of brewing in Europe. For more information, see Filippo Maria Gambari, The development of fermented beverages in the prehistory and protohistory of Cisalpine, based on archaeological and linguistic data; and Filippo Maria Gambari, Fermented beverages in northwestern Italy.

[5] Depending on the era, the Great Mother took on different faces and names, and in this precise area she was venerated above all in her aspect as virgin goddess of woods, stones, waters, earth, women, but also of beauty and harmony of nature. This is demonstrated by a cippus from the XNUMXst-XNUMXnd century AD found in the Oratory of San Vincenzo, a few steps from the Preja Buja, which had long been used as a support for the stoup. The cippus bears this inscription: "By command and order / of the celestial Diana Augusta, / to the gods and goddesses / all together, Gaius Elpius (?) / for himself with his mother and children / all, dissolved the vow.” The inscription is explained thus: “By inspiration, probably in sleep, of the goddess Diana (…) a devotee with an uncertain name was induced, for his own good and that of his, to formulate a vow addressed to both gods and goddesses. Diana's formula of inspiration and offering to all deities are rare; but a very unique case so far is that they are referred to as “united, all together” (…).” (See Antonio Sartori, "The Roman epigraphs of the Sesto Calende Museum", in Maria Adelaide Binaghi and Mauro Squaranti, The archaeological collection and the territory, p. 160). The stele is therefore extremely important, and its presence on site suggests that the site itself was considered sacred and dear to many gods and goddesses, especially Diana. Considering the continuity of worship in the area, it is therefore possible to imagine that the Diana whose name was carved in stone in the Imperial Roman age had passed through the Roman interpretation, and derived from a previous divinity who embodied his same characteristics. A deity honored with another name, or perhaps without any name, who equally represented the spirit of woods, stones, waters, earth, as well as women and in general of all nature. A divinity that was also celebrated in the other sites of the Cisalpine where stelae similar to this one were found, and which, again for continuity of worship, perhaps resembled the one to which our priestess was dedicated in an even more distant era.

[6] In his text, de Marinis explains: “The tomb [of the tripod], moreover, it illustrates in an exemplary way a characteristic phenomenon of the Golasecca culture between the middle of the sixth and the beginning of the fifth century BC: the richest tombs in this period are female and alongside luxury ornamental objects they also have specialized furnishings ritual, as is the case of the tripod or in the contemporary tombs of the Cà Morta the so-called doublers or in Albate the elaborate vase with a high foot, three arms and three ornithomorphic gutti.”. See Raffaele Carlo de Marinis, on. cit., p. 27;

[7] Ibid., p. 19;

[8] Ibid., p. 25;

[9] Ibid., p. 21;

[10] Ibid., p. 23;

[11] See Camillo Leone, "Some objects discovered in Pezzana in the Vercelli area", in AA.VV., Proceedings of the Society of Archeology and Fine Arts for the Province of Turin, p. 247-254; and Raffaele Carlo de Marinis, on. cit., pp. 23-24;

[12] See Raffaele Carlo de Marinis, on. cit., p. 25.

REFERENCES

- AA.VV. - Proceedings of the Society of Archeology and Fine Arts for the Province of Turin – Fratelli Bocca – Rome-Turin-Florence 1887;

- Maria Adelaide Binaghi and Mauro Squaranti (edited by) – The archaeological collection and the territory - Civic Museum of Sesto Calende – Sesto Calende 2000;

- Lucina Anna Rita Candy – “From Sass da Preja Buja to San Donato: a 5.000-year history"- in Sanctuary. III International Congress. Sanctuaries, Culture, Art, Pilgrimage, Scenery, People – Villanova 2016;

- Raffaele Carlo De Marinis – The necropolis of Mulini Bellaria in Sesto Calende (excavations 1977-1980) – Rome 2009;

- Raffaele Carlo De Marinis, Serena Massa, Maddalena Pizzo – At the origins of Varese and its territory – Bretschneider's herm – Rome 2009;

- Filippo Maria Gambari – Fermented beverages in northwestern Italy – The oldest beer – Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities;

- Filippo Maria Gambari – “The development of fermented beverages in the prehistory and protohistory of Cisalpine, based on archaeological and linguistic data” – in Prehistory of Food. 50th Scientific Meeting of the Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory – Rome 2015;

- Marija Gimbutas – The Language of the Goddess – Venexia Publishing – Rome 2008;

- Marija Gimbutas – The Goddesses and Gods of Ancient Europe – Alternative Press – Viterbo 2016;

- Barbara Grassi – “Kits of the first Golasecca phase from Sesto Calende (VA)” – in Archaeological magazine of the ancient Diocese of Como – Volume N. 195 – Year 2013 – New Press – Como 2014;

- Barbara Grassi, Claudia Mangani (edited by) – In the forest of the ancestors. The necropolis of Monsorino di Golasecca – Under the banner of Giglio - Florence 2016;

- Barbara Grassi, Madalena Pizzo (edited by) – “Gallorum Insubrum Fines: archaeological research and projects in the Varese area"- in Proceedings of the Study Day (Varese – Villa Recalcati 29 January 2010) – The Herm of Bretschneider – Rome 2014;

- Maurizio Harari (edited by) – The territory of Varese in prehistoric and protohistoric times – Nomos Edizioni – Busto Arsizio 2017;

- Rosanna Janke - "From beer to wine: archaeological evidence in Canton Ticino between prehistory and Roman times" - in Bulletin of Swiss Archaeology – 2006;

- Rites and Cults in the Iron Age – Conferences June 1998 Municipality of Sesto Calende – Cultural Committee of the Joint Research Center of Ispra – Civic Museum of Sesto Calende – Sesto Calende 1999.