Every year, in November, Venetians go on pilgrimage to one of the most beautiful churches in the city: Santa Maria della Salute.

The Celebration of Madonna della Salute is the feast of the Madonna della Salute, testimony to the close relationship between Venice and religious sentiment which, in this case more than ever, is lived in a very intimate, I dare say almost visceral way and, not by chance, is an event not very well known and experienced by tourists.

But what is its origin?

Keep reading my article and I will explain it to you!

The origins of the celebration: from plague to health

The ex voto of the Senate and the project of Baldassarre Longhena

Once the decision was made to build the church, the first question to be resolved was the choice of the architect to design the structure. A competition was held to award the then thirty-three year old Baldassarre Longhena, who explained his project to the Senate in the following words:

"I have formed a church in the form of a rotunda, a work of invention nova, and never made ninna in Venetia, a work very worthy and desired by many (...) that God Benedict has lent me to make it in the form of a crown to be dedicated to the Virgin Mary."

His profound knowledge of Scamozzi, of whom he was a pupil, and of Palladio's architecture certainly played a decisive role in the design of the basilica.

In fact, Palladio had tried to erect a round church in the splendid lagoon city, but without ever succeeding in his intention. In all probability, Longhena took up this challenge, this time creating one of the most beautiful and admired architectural structures in the world.

Once the architect had been chosen, there remained one last question to resolve: where to build it?

At first, Senator Gerolamo Soranzo had proposed the most extreme area of Punta della Dogana. Of course, this position would have perfectly expressed the symbolic value that the Serenissima attributed to the construction, but it posed many problems related to urban planning in general, and would have involved moving the customs house itself.

However, the choice of location was very close to the first proposal and the basilica was built in an area slightly further back than the Punta della Dogana, in the Sestiere di Dorsoduro, a location of great prestige and visibility, which would change the city's skyline forever.

The first stone was laid on 25 March 1631. This date is not accidental and rich in symbolism, since it corresponds to the mythical foundation of Venice in 142.

The Basilica of Santa Maria della Salute: a bold and majestic construction

What makes the majestic building even more particular is the presence of two perfectly symmetrical bell towers on either side of the apse. But the most striking elements are the spiral-shaped buttresses that embrace the octagonal upper drum and give the massive structure greater momentum and movement, further highlighting the monumental dome. Above this is the lantern, a tall structure with a columned balustrade at the base from which eight obelisks rise to symbolise the tips of a crown. The structure is closed by a small dome on the top of which there is a statue of Mary holding a stick that dominates and protects the lagoon and the city: this element was generally attributed to the commanders of the Venetian fleets and shows the will of the Senate to place the fate of the city in the hands of the Virgin.

Note: the difficulty of constructing such a large dome on an octagonal base with a very unstable ground such as that of Venice was overcome by the great architect thanks to a series of expedients including the insertion of these buttresses. But the grandeur of the project can be seen in Longhena's ability to make these load-bearing elements also highly decorative, combining aesthetics and function in a masterful way, which have made these spirals one of the most characteristic symbols of the whole city. Other tricks involved, instead, the use of narrow pillars and very thin walls and the construction of the dome itself with a masonry intrados and a light intrados made of wood. The foundations were also reinforced with the use of a considerable number of piles, mostly made of larch, about one million! On top of these poles, then, a laterite base was erected, which was to form the foundations of the floor of the building. The result? One of the buildings in Venice that has never succumbed!

Inside the Basilica

The flooring is also very beautiful: black, white, yellow Siena marble and red Verona marble are used by Longhena to create graphic effects that all converge towards the centre of the main body where one of the symbolic elements of the structure, a black disc with an inscription in Latin that reads "Unde origo, inde salus" or "Where the origin is, is salvation", is placed exactly under the splendid 17th century chandelier. The phrase indicates that just as the city of Venice was created by the Virgin, so will it be freed from the plague. Normally banned from passage with the help of red ropes, this inscription plays a central role in the Feast of Health during which the faithful rub their feet, convinced of its beneficial influence.

Behind the altar there are statues of saints protectors against the plague and the choir, a wooden sculpture most probably made by Longhena himself, above which there is the organ built by Francesco Dacci.

Finally, the sacristy where you can admire works of art by Titian, Tintoretto and other minor authors.

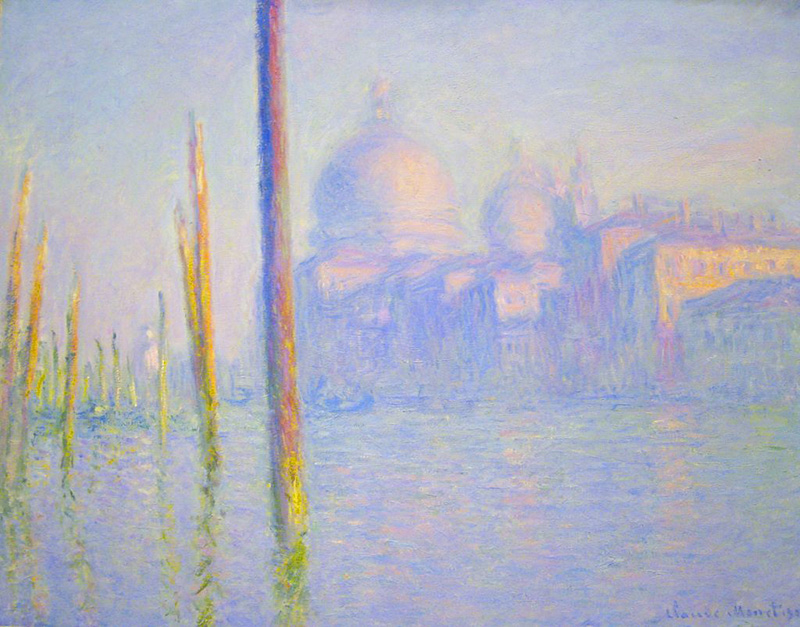

The Basilica of Health in modern art

The Celebration of Madonna della Salute 2020: the renewal of a vow

The Celebration of Madonna della Salute, traditionally held every 21st November, has always represented a very important moment in the life of citizens who have never abandoned this occasion. Probably, this year the festival will be of further importance precisely because of the particular health situation that the whole world is going through. In a certain sense the words of Albert Camus describing the feeling at the time of the plague still resonate today full of value:

The plague had covered everything: there were no longer individual fates, but a collective history, the plague, and feelings shared by all.

And it is precisely in an attempt to exorcise this new enemy that the City of Venice, albeit with the necessary precautions, has decided to give thanks to Our Lady of Health again this year.

Let's see in more detail what the festival will be like in this 2020.

The traditional votive bridge, which usually connects the two banks of the Grand Canal, will not be installed. There will not even be the traditional markets where we Venetians usually love to stop and buy the typical sweets of this festival and the traditional dish: the castradina. In order to guarantee a regular flow of people as far as possible, a precise route has been devised that will characterise the festivities. In this sense, the access to the Basilica between the 19th and the 22nd will be allowed only through the central door. The faithful will be able to continue, as per tradition, along the central nave to the main altar, where they will be able to worship the icon of the Madonna della Salute. The route then includes the passage through the sacristy and to the seminary premises which will lead to the exit on the Salute field, all this will take place with limitations in the number of people.

On 21st November, masses will be celebrated only at the beginning and end of the day with a reduced number of faithful. The 11 a.m. mass, presided by Patriarch Francesco Moraglia, will be broadcast live on Antenna 3 and on Gente Veneta's Facebook profile.

During the whole time of the festivities, it will not be possible for the pilgrims to light the votive candles which will have to be placed in boxes along the route and which will be lit later by volunteers.

Lascia un commento