Untitled

Untitled

Untitled

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

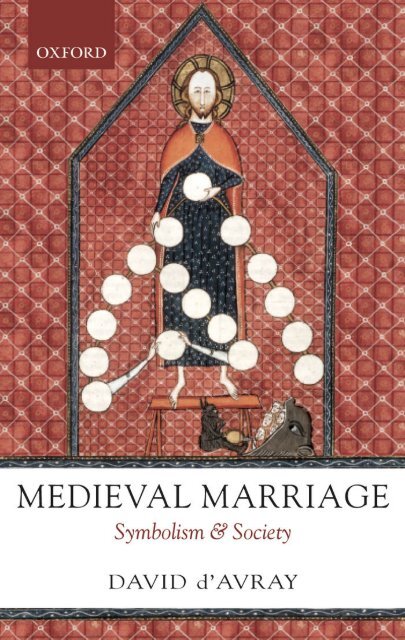

MEDIEVAL MARRIAGE

This page intentionally left blank

Medieval Marriage<br />

<br />

Symbolism and Society<br />

D. L. d’AVRAY

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26dp<br />

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.<br />

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,<br />

and education by publishing worldwide in<br />

Oxford New York<br />

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai<br />

Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata<br />

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi<br />

S~ao Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto<br />

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press<br />

in the UK and in certain other countries<br />

Published in the United States<br />

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York<br />

ã D. L. d’Avray 2005<br />

First published 2005<br />

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,<br />

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,<br />

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,<br />

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate<br />

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction<br />

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,<br />

Oxford University Press, at the address above<br />

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover<br />

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer<br />

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data<br />

Data available<br />

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data<br />

Data available<br />

ISBN 0–19–820821–9<br />

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2<br />

Typeset by John Wa‹s, Oxford<br />

Printed in Great Britain<br />

on acid-free paper by<br />

Biddles Ltd., King’s Lynn, Norfolk

UXORI CARISSIMAE

This page intentionally left blank

Acknowledgements<br />

The following are among those who have earned my gratitude. The<br />

Archivio Segreto Vaticano Prefect and sta·, Louis-Jacques Bataillon,<br />

Nicole B‹eriou, John Blair, Paul Brand, Paul Brennan, Martin<br />

Brett, the British Academy for a Research Readership to work on<br />

this project and for microfilm, Christopher Brooke, Jim Brundage,<br />

Peter Clarke, Stephen Davies, Trevor Dean, Sally Dixon-Smith,<br />

Gero Dolezalek, Charles Donahue, Jenifer Dye, Barbara Harvey,<br />

Julian Hoppit, Olwen Hufton, Robert Lerner, my Love and Marriage<br />

Special Subject classes, in which some brilliant students have<br />

taught me a lot, David Luscombe, Patrick Nold, the ocials of the<br />

Penitenzieria Apostolica for permission to use their archive, Catherine<br />

Rider, Kirsi Salonen, Ludwig Schmugge, R•udiger Schnell, Julia<br />

Walworth (both as uxor carissima and as Merton Fellow Librarian),<br />

John Wa‹s, Chris Wickham, and Anders Winroth.<br />

D.L.d’A.<br />

December 2004

This page intentionally left blank

Contents<br />

Note on Transcriptions xii<br />

Abbreviations xii<br />

Introduction 1<br />

1. Mass Communication 19<br />

(a) Preliminaries 19<br />

(b) TheEarlyMiddleAges 20<br />

(c) Mass Communication in the Age of the Friars 37<br />

(d) The Message about Marriage 58<br />

2. Indissolubility 74<br />

(a) From the Roman Empire to the Carolingian Empire 74<br />

(b) c.800–c.1200 82<br />

(c) The Age of Innocent III 99<br />

(d) Indissolubility in Practice 108<br />

3. Bigamy 131<br />

(a) Bigamy and Becoming a Priest 131<br />

(b) The Marriage Ceremony 141<br />

(c) Clerics in Minor Orders 157<br />

4. Consummation 168<br />

(a) Consummation and the Medieval Church’s Idea of<br />

Sex 168<br />

(b) The Dissolution of the Unconsummated Marriage:<br />

From Hincmar to Alexander III 176<br />

(c) The Social E·ects of Alexander III’s Decision 180<br />

(d) Long-Term Developments 188<br />

Conclusion 200

x Contents<br />

DOCUMENTS<br />

Chapter 1<br />

1. 1. Marriage symbolism in the Bavarian Homiliary 208<br />

1. 2. Homily on the text ‘Nuptiae factae sunt’ (John 2: 1) in<br />

the Bavarian Homiliary 211<br />

1. 3. Marriage symbolism in the Beaune Homiliary 214<br />

1. 4. Nonconformist variants in Hugues de Saint-Cher 217<br />

1. 5. Nonconformist variants in Jean de la Rochelle 217<br />

1. 6. Nonconformist variants in Pierre de Saint-Beno^§t 218<br />

1. 7. Nonconformist variants in G‹erard de Mailly 218<br />

1. 8. Nonconformist variants in Guibert de Tournai 219<br />

1. 9. A sermon on marriage by Jean Halgrin d’Abbeville 219<br />

1. 10. A sermon on marriage by Konrad Holtnicker 223<br />

1. 11. A sermon on marriage by Servasanto da Faenza 226<br />

1. 12. A sermon on marriage by Aldobrandino da Toscanella<br />

(Schneyer no. 404) 232<br />

1. 13. A sermon on marriage by Aldobrandino da Toscanella<br />

(Schneyer no. 48) 238<br />

Chapter 2<br />

2. 1. Proof in ‘forbidden degrees’ cases: Hostiensis attacks<br />

laxity 242<br />

2. 2. Proof in ‘forbidden degrees’ cases: the rigorism of<br />

Hostiensis 246<br />

Chapter 3<br />

3. 1. Johannes de Deo, De dispensationibus, on bigamy 249<br />

3. 2. Innocent IV (Sinibaldo dei Fieschi) on Decretals of<br />

Gregory IX, X. 5. 9. 1: bigamy and loss of clerical<br />

status 250<br />

3. 3. Innocent IV (Sinibaldo dei Fieschi) on Decretals of<br />

Gregory IX, X. 1. 21. 5: the symbolic understanding<br />

of bigamy 251<br />

3. 4. Bull of Pope Alexander IV to the prelates of France 253<br />

3. 5. Bull of Pope Gregory X to King Philip III of France 254<br />

3. 6. Bull of Pope John XXII to King Philip V of France 254<br />

3. 7. Bull of Pope John XXII to King Charles IV of France 255<br />

3. 8. Questions on marriage in MS London, BL Royal<br />

11. A. XIV 256

Contents xi<br />

3. 9. Passage on bigamy in the Pupilla oculi of Johannes de<br />

Burgo 262<br />

3. 10. A ‘bigamy’ case from the gaol delivery rolls (6 June<br />

1320) 265<br />

3. 11. The case of Five-Wife Francis, from the archive of the<br />

Apostolic Penitentiary 267<br />

3. 12. The case of Petrus Martorel, from the archive of the<br />

Apostolic Penitentiary 269<br />

Chapter 4<br />

4. 1. Consummation and its consequences in a canon-law<br />

commentary: a link to late medieval papal dissolutions<br />

of ratum non consummatum marriages 270<br />

4. 2. Ricardus de Mediavilla: marriage and entry into a<br />

religious order before consummation 273<br />

4. 3. Ricardus de Mediavilla on the marriage of Mary and<br />

Joseph 275<br />

4. 4. A consummation case in the papal registers<br />

(John XXII) 276<br />

4. 5. Consummation and indissolubility in the Oculus<br />

sacerdotis of William of Pagula 282<br />

4. 6. Johannes de Burgo on the marriage of Mary and Joseph 283<br />

4. 7. A case from the archive of the Apostolic Penitentiary:<br />

Constance of Padilla 285<br />

4. 8. Another non-consummation case from the archive of<br />

the Apostolic Penitentiary 286<br />

Bibliography 288<br />

Index of Manuscripts 310<br />

General Index 312

Note on Transcriptions<br />

My transcription conventions are explained in detail in previous<br />

books (The Preaching of the Friars: Sermons Di·used from Paris<br />

before 1300 (Oxford, 1985), xi; Death and the Prince: Memorial<br />

Preaching before 1350 (Oxford, 1994), 7–8; Medieval Marriage Sermons:<br />

Mass Communication in a Culture without Print (Oxford,<br />

2001), 43). An asterisk before a word indicates the presence of an<br />

error too trivial to deserve specifying. In the present volume I normalize<br />

‘d’ to ‘t’ in ‘sicut’, and ‘t’ to ‘d’ in ‘sed’; and ‘n’ to ‘m’ in<br />

words like ‘comprobatum’, ‘imprecatur’, ‘immo’, and ‘tempore’.<br />

The problem arises because the letter is often swallowed up in an<br />

abbreviation and there is no standard classical or medieval orthography.<br />

I have normalized in these cases even where, as occasionally<br />

happens, the other form is written in full: e.g. sicud or inprecatur.<br />

Abbreviations<br />

BAV Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana<br />

BL British Library<br />

BN Biblioth›eque Nationale de France<br />

Migne, PL J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Latina<br />

MS/ms. Manuscript<br />

X. Decretals of GregoryIX (X. 2. 20. 47 =book 2, titulus<br />

20, chapter 47 of the Decretals)

Introduction<br />

How the modern intellectual sees medieval marriage<br />

For centuries in Europe, formal marriage was a private contract between<br />

landed families, designed to insure that property remained within a particular<br />

lineage. In the upper classes, families essentially married other families,<br />

forging political alliances and social obligations among relatives and kin.<br />

It was during the Reformation, with the emergence of the early Protestant<br />

idea of ‘companionate marriage,’ that the emotional bond between husband<br />

and wife came to be seen as an end in itself. As the social historian<br />

Lawrence Stone noted, this was a marked departure from the Catholic idea<br />

of chastity, which considered earthly marriage a more or less unfortunate<br />

necessity meant to accommodate human weakness; ‘It is better to marry<br />

than to burn,’ St. Paul had said, but he made it sound like a close call. So<br />

when the Puritans wrote of husbands and wives as mutually respectful and<br />

a·ectionate partners they were moving towards a new understanding of<br />

marriage as a kind of spiritual friendship.<br />

It is too easy for scholars to forget what the non-specialist intelligentsia<br />

thinks about their field, and the New Yorker is a good place<br />

to find out. Such a caricature in such a high-quality magazine reminds<br />

one of the time lag between research and general educated<br />

awareness. Not everything is wrong. Marriages were a mechanism<br />

for linking families and family fortunes in the Middle Ages as<br />

in subsequent ages up until and including the nineteenth century.<br />

Still, most of the rest is wrong. It was not always the family that had<br />

power. In some periods and regions lords controlled marriages of<br />

those who held land from them. Free choice by individuals was an<br />

A. Haslett, ‘A Critic at Large’, New Yorker (31 May 2004), 76–80 at 76.<br />

See e.g. R. Bartlett, England under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075–1225<br />

(Oxford, 2000), 549–51; A. Molho, Marriage Alliance in Late Medieval Florence<br />

(Cambridge, Mass., etc., 1994), passim.<br />

See e.g. Bartlett, England under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075–1225,<br />

547–9; R. Boutruche, Seigneurie et f‹eodalit‹e: l’apog‹ee (XIe–XIIIe si›ecles) (Paris,<br />

1970), 229–30; G. Duby, Medieval Marriage: Two Models from Twelfth-Century<br />

France, trans. E. Forster (Baltimore etc., 1978), 97–8 (there was no published French<br />

edition); J. B. Freed, Noble Bondsmen: Ministerial Marriages in the Archdiocese of<br />

Salzburg, 1100–1343 (Ithaca, NY, etc., 1995); S. L. Waugh, The Lordship of England:

2 Introduction<br />

important factor in the later Middle Ages, with backing from the<br />

Church. Marital a·ection was a social reality (as common sense<br />

would suggest), and it was strongly encouraged by influential texts.<br />

None of this is at all new, though clearly a reminder is not superfluous.<br />

This book aims to bring out a di·erent dimension of the<br />

social history of medieval marriage, correcting from another angle<br />

the idea that it was driven mainly by the landed ambitions of families.<br />

Social and legal practice was infused with marriage symbolism.<br />

Symbolism gave meaning to practice and a·ected it, not least by<br />

helping to create a combination of monogamy and indissolubility<br />

probably unique in the history of literate societies.<br />

Marriage symbolism in religions<br />

The theme, then, is marriage symbolism’s e·ect on social practice.<br />

Symbolism was crucial in the theory of marriage first, and even<br />

before the Middle Ages began. Central to the meaning of marriage,<br />

symbolism eventually became part of marriage law and changed<br />

behaviour through law, the decades around 1200 marking a turning<br />

point.<br />

I shall start with a rapid glance at the comparative religious history<br />

of the topic. Then I shall briefly indicate the kind of work<br />

that has already been done on medieval Western marriage symbolism.<br />

That will be balanced by the most rapid tour d’horizon<br />

of recent work on the social history of medieval marriage, since<br />

I aim to bring it together with the history of marriage symbolism.<br />

Like food, love and marriage are the basis of strong religious<br />

symbolism. In the study of comparative religion there is a keyword<br />

for it: ‘sacred marriage’ or hieros gamos. An important variety is<br />

parallelism between the marriage of two gods and the marriage of<br />

Royal Wardships and Marriages in English Society and Politics 1217–1327 (Princeton<br />

etc., 1988).<br />

See below, pp. 124–9.<br />

F. M. Powicke, King Henry III and the Lord Edward: The Community of the<br />

Realm in the Thirteenth Century (2 vols.; Oxford, 1947), i. 157 n. 1.<br />

See below, pp. 69, 129; also A. MacFarlane, Marriage and Love in England, 1300–<br />

1840: Modes of Reproduction (Oxford, 1986), 182–3, to show that a non-medievalist<br />

can get it right. Scholars have known all this for a long time: see e.g. H. A. Kelly,<br />

Love and Marriage in the Age of Chaucer (Ithaca, NY, 1975).<br />

K. W. Bolle, ‘Hieros Gamos’, in M. Eliade (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Religion,<br />

vi (New York etc., 1987), 317–21.

Introduction 3<br />

ordinary men and women. It can be found in ancient Mesopotamia,<br />

and it has been studied quite recently as living religion in a south<br />

Indian temple. In the second case we know a lot about it. The<br />

marriage ritual between the two gods is represented by statues in<br />

the temple. If the gods do not consummate the marriage regularly,<br />

the female becomes a dangerous force and a general threat.<br />

This temple ritual belongs to one of the main types of marriage<br />

symbolism in the world history of religions: the union of a male and<br />

a female god, mirroring the union of man and woman in marriage.<br />

There are a number of such marriages or sexual relationships in<br />

the Hindu pantheon: notably Rama and Sita, Vishnu and Laksmi,<br />

Siva and Parvati, Krishna and Radha. With the last two pairs<br />

at least the female partner can be presented as human or quasihuman,<br />

as we shall see. However, the motif of the marriage of two<br />

unambiguously divine beings has in itself only a loose relation to<br />

the argument of this book. Analogy between the marriage of two<br />

gods and marriage of human to human is not the same as analogy<br />

between human union with God and marriage of human to human.<br />

Non-Christian cases of this second sort of symbolism are harder<br />

to find. Some promising possibilities turn out on inspection to be<br />

very di·erent from the symbolism with which we are concerned.<br />

There is a scholarly literature on what looks at first like the same<br />

kind of thing in ancient Mesopotamia: a mythical human hero,<br />

represented by a king, who wins the love of a goddess. The story<br />

has even been connected with the Song of Songs, subject of St<br />

Bernard’s famous sermons, which would bring it even closer to<br />

our theme. However, the stories or putative rituals may have had<br />

another meaning—say the celebration of the king’s prowess in love<br />

as in everything else—and the whole subject is too fraught with<br />

controversy to be drawn into our argument.<br />

G. Leick, Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature (London etc., 1994),<br />

ch. 12.<br />

C. J. Fuller, ‘The Divine Couple’s Relationship in a South Indian Temple:<br />

Minaksi and Sundare‹svara at Madurai’, History of Religions, 19 (1980), 321–48.<br />

For an interesting analysis of di·erent types of relationship see F. A. Marglin,<br />

‘Types of Sexual Union and their Implicit Meanings’, in J. S. Hawley and D. M.<br />

Wul· (eds.), The Divine Consort: Radha and the Goddesses of India (Berkeley, 1982),<br />

298–315.<br />

S. N. Kramer, The Sacred Marriage Rite: Aspects of Faith, Myth, and Ritual in<br />

Ancient Sumer (Bloomington, Ind., etc., 1969), esp. ch. 5.<br />

Leick, Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature, ch. 11, on ‘“Words of<br />

Seduction”: Courtly Love Poetry’, argues against ‘the neo-primitive “fertility rite”

4 Introduction<br />

The ancient Greek stories in which gods and humans mate do<br />

not on the whole look like symbols of non-sexual love betweeen<br />

thedivineandthehuman. A possible exception is the marriage<br />

of the god Dionysus to the ‘Basilinna’, the wife of the Archon<br />

Basileus (‘ruler-king’, literally, the member of the panel of rulers at<br />

Athens most especially responsible for sacred a·airs). In this case<br />

a marriage ritual may stand for the union of human and divine.<br />

In Hindu India at least marriage can represent the union of<br />

human and divine. There is even a specific name for this kind<br />

of passionate devotion to a god: ‘Bhakti’. The love of Radha and<br />

the god Krishna is particularly relevant. Radha would stand for<br />

the human side. There is a problem: Radha herself has a ‘claim<br />

to divinity’. Still, at least sometimes the idea of Radha seems<br />

to gather up in it the idea of a devout person’s union with the<br />

divine. As one historian of religion has commented: ‘As the feminine<br />

worldward side of the masculine–feminine Radha–Krishna she is<br />

the tie between deity and all souls, since she is one with the gopis<br />

[milkmaids or cowgirls, co-lovers with Radha of Krishna] and thus<br />

with those whom the gopis represent, namely all humankind.’ The<br />

notion that the construct of Sacred Marriage implies’ (129; on the king’s prowess,<br />

109–10). If she is right, one cannot use without reservation the conclusions of<br />

Kramer. For further references on the debate about ‘sacred marriage’ in ancient<br />

Mesopotamia see A. Kuhrt, ‘Babylon’, in E. J. Bakker, I. J. F. De Jong, and H.<br />

van Wees (eds.), Brill’s Companion to Herodotus (Leiden etc., 2002), 475–96 at 492<br />

n. 37. In the foregoing (not only on Mesopotamia) I have been helped by Kuhrt’s<br />

clear distinction between two kinds of sacred marriage: ‘one is the marriage of two<br />

gods, represented by their statues; the other a ceremony during which the goddess<br />

of erotic love, Inanna/Ishtar (represented by a priestess?), and the king in the guise<br />

of her mythical lover, Dumuzi, had intercourse’. It is the second kind which is the<br />

subject of dispute.<br />

On the whole subject see A. Avagianou, Sacred Marriage in the Rituals of Greek<br />

Religion (Europ•aische Hochschulschriften, ser. 15, 54; Berne etc., 1991).<br />

‘We could explain this strange and unique ritual in Greek religion as the legitimized<br />

σµµειξις of divine and human via marriage’ (Avagianou, Sacred Marriage<br />

in the Rituals of Greek Religion, 200).<br />

Cf. Hawley, ‘A Vernacular Portrait: Radha in the Sur Sagar’, in Hawley and<br />

Wul·, The Divine Consort, 42–56 at 56.<br />

N. Hein, ‘Comments: Radha and Erotic Community’, in Hawley and Wul·,<br />

The Divine Consort, 116–24 at 120, commenting on Hawley’s paper. Max Weber<br />

has some good remarks on the love of Krishna, and his parallel with Pietism is helpful:<br />

‘Was der alten klassischen Bhagavata-Religiosit•at zun•achst noch fehlte oder<br />

jedenfalls—wenn es in ihr schon existierte—von der vornehmen Literatenschicht<br />

nicht rezipiert wurde, war die br•unstige Heilandsminne der sp•ateren Krischna-<br />

Religiosit•at. A• hnlich wie etwa die lutherische Orthodoxie die psychologisch gleichartige<br />

pietistische Christus-Liebe (Zinzendorf) als unklassische Neuerung ablehnte’

Introduction 5<br />

role of these gopis accentuates the human side.<br />

There are other problems. The love of Krishna and Radha (not<br />

to mention the other gopis) is sensual in the extreme—too much so<br />

for a divine message? Perhaps not. Look at the following passage<br />

from Mechtild of Magdeburg, a thirteenth-century female mystic<br />

in the spiritual tradition of Bernard of Clairvaux.<br />

‘Stay, Lady Soul.’<br />

‘What do you bid me, Lord?’<br />

‘Take o· your clothes.’<br />

‘Lord, what will happen to me then?’<br />

‘Lady Soul, you are so utterly formed to my nature<br />

That not the slightest thing can be between you and me.’<br />

...<br />

Then a blessed stillness<br />

That both desire comes over them.<br />

He surrenders himself to her,<br />

And she surrenders herself to him.<br />

What happens to her then—she knows—<br />

And that is fine with me.<br />

But this cannot last long.<br />

When two lovers meet secretly,<br />

They must often part from one another inseparably.<br />

At least since St Bernard a surface sensuality has been part of the<br />

discourse of Christian mysticism.<br />

It might be objected that the love a·air of Krishna and Radha is<br />

extra-marital. Then again, she is one of many lovers of Krishna.<br />

Does his polygyny nullify the analogy with the medieval West?<br />

(Die Wirschaftsethik der Weltreligionen: Hinduismus und Buddhismus (1916–20),<br />

repr. in Gesammelte Aufs•atze zur Religionssoziologie, ii. Hinduismus und Buddhismus<br />

(T •ubingen, 1988), 198). Weber also mentions the ‘br•unstige kultische Minne zu<br />

pers•onlichen Nothelfern, welche als Fleischwerdung gro¢er erbarmender G•otter<br />

galten’ (ibid. 202) of the popular ‘orgiastic’ religion rejected by Brahman intellectuals.<br />

There is a large literature on Mechtild. See e.g. A. Hollywood, The Soul as<br />

Virgin Wife: Mechtild of Magdeburg, Marguerite Porete, and Meister Eckhart (Studies<br />

in Spirituality and Theology, 1; Notre Dame etc., 1995), 1–2, and chs. 3 and 7;<br />

H. E. Keller, My Secret is Mine: Studies on Religion and Eros in the German Middle<br />

Ages (Leuven, 2000), 107–10, with further bibliographical references. Mechtild’s<br />

Flowering Light of Godhead, from which the passage quoted comes, was probably<br />

composed in or near the third quarter of the thirteenth century (ibid. 108).<br />

Mechtild of Magdeburg, The Flowing Light of the Godhead, trans. and intro. F.<br />

Tobin (New York etc., 1998), 62; cf. B. Newman, From Virile Woman to Woman-<br />

Christ: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature (Philadelphia, 1995), 150.

6 Introduction<br />

These objections fade on closer inspection even if they do not entirely<br />

disappear. The passion of Krishna and Radha may be extramarital<br />

or even adulterous in some versions, but one line strongly<br />

represented in Hindu theology is that they were in reality married.<br />

The other passionate cowgirls can be understood as di·erent forms<br />

of Radha herself. Anyway, one must not be too literal-minded<br />

with this sort of religious language. The Western image of God<br />

as the bridegroom of enormous numbers of soul-brides could be<br />

understood as polygamy, but this would be clumsy. Medieval Western<br />

marriage sermons sometimes built their symbolism around an<br />

Old Testament story: Esther’s triumphant displacement of Vashti<br />

as wife of the Persian king. In context this is clearly not an endorsement<br />

of divorce. With any symbol the analogy breaks down<br />

somewhere, and the trick is to know when to stop pressing the<br />

comparison (a principle very relevant to gendered imagery).<br />

The union of the the male god Siva with his wife Parvati can also<br />

symbolize the union of human and divine. As a standard reference<br />

work puts it, ‘Their marriage is a model of male dominance with<br />

Parvati docilely serving her husband, though this is also a model<br />

of the way a mortal should serve the god.’ It is true that Parvati<br />

is also a goddess, but a goddess close to humanity. Thus humans,<br />

women at least, can assimilate their religious experience to Parvati’s<br />

loving devotion to her husband. ‘Parvati, the daughter of the<br />

mountain Himalaya, is an ambiguous semi-divinity . . . Although<br />

poetic metaphors accorded her divine status, she is the quintessence<br />

of the lowly mortal woman worshipping the lofty male god.’<br />

It is true that this description cannot be simply applied to Christian<br />

marriage symbolism. There may indeed be a tendency in Christian<br />

mysticism towards gender specialization—human woman as<br />

Hawley, ‘A Vernacular Portrait’, 53; D. M. Wul·, ‘Radha: Consort and Conqueror<br />

of Krishna’, in J. S. Hawley and D. M. Wul· (eds.), Devi: Goddesses of India<br />

(Berkeley etc., 1996), 109–34 at 133 n. 30.<br />

S. Goswami, ‘Radha: The Play; and Perfection of Rasa’, in Hawley and Wul·,<br />

The Divine Consort, 72–88 at 81: ‘the many gopis are but manifestations of the body<br />

of Radha’. (This represents the point of view of a modern devotee.).<br />

D. L. d’Avray, Medieval Marriage Sermons: Mass Communication in a Culture<br />

without Print (Oxford, 2001), index, s.v. ‘Assuerus’.<br />

Article on ‘P»arvat»§’, in J. Bowker (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of World Religion<br />

(Oxford, 1997), 737.<br />

W. D. O’Flaherty, ‘The Shifting Balance of Power in the Marriage of Siva and<br />

Parvati’, in Hawley and Wul·, The Divine Consort, 129–43 at 135. (The comment<br />

relates to a specific set of sources.).

Introduction 7<br />

bride, notably—but either sex can take the female role in the symbolic<br />

register, as is evident from Bernard of Clairvaux’s sermons on<br />

the Song of Songs, where the monks are the bride. Nevertheless,<br />

the following simple and powerful idea is shared by Christianity<br />

and Hinduism: that union between humans and the divine is like a<br />

marriage.<br />

Hinduism also shares with Catholic Christianity a strong doctrine<br />

of the indissolubility of marriage. The correlation with the similar<br />

approach to marriage symbolism is significant and should be borne<br />

in mind by readers following the argument of this book. There is<br />

no sociological entailment here, no necessity, but the ideal type of a<br />

relation between the social rule of unbreakable marriage and highly<br />

developed marriage symbolism makes sense.<br />

In Christian spirituality it is the ‘soul–God =bride–bridegroom’<br />

imagery which comes closest to Hinduism. Another variant of marriage<br />

symbolism, the image of the Church as bride of Christ, is further<br />

away from Hindu analogues. This is because of its collective or<br />

corporate community character, the idea of ‘the Church’ and even<br />

the human race as in some sense a unity, capable of being collectively<br />

infected by original sin and collectively redeemed by Christ.<br />

So far as one can generalize, Hinduism does indeed emphasize the<br />

character of the whole universe as a collective whole, but much less<br />

so the human race, or the collective identity of a society within it. In<br />

Hinduism there is the self (atman), there are status groups (castes)<br />

through which the self passes on the journey of reincarnations towards<br />

final release, and there is the All, but the idea of a society as<br />

an organic body with a collective role in the drama of History is<br />

alien. The medieval Church saw itself as just such a society, whose<br />

relation to God could be called a marriage.<br />

To this symbolism the closest parallel is in ancient Israel, where<br />

the Jewish people are themselves, collectively, the bride of God.<br />

It has been pointed out that according to Deuteronomy 24: 1–4 ‘a<br />

divorced woman who has remarried can never be reconciled with<br />

her former husband. Because God is anxious to bring back Israel<br />

as his beloved spouse, he must never have divorced her.’<br />

Keller argues that ‘the roles of bride and bridegroom become fixed with regard<br />

to gender’, suggesting that there was a ‘gradual narrowing of the role of the bride to<br />

(primarily religious) women on the one hand’ and a ‘successive masculinization of<br />

the divine bridegroom on the other hand’ (My Secret is Mine, 8).<br />

See, however, below, n. 36.<br />

C. Stuhlmueller, ch. 22 on ‘Deutero-Isaiah’, in The Jerome Biblical Commen-

8 Introduction<br />

The Song of Songs may or may not be about the love of God<br />

and his people, but in any case this religious interpretation of these<br />

songs is the ‘oldest interpretation, in both Christian and Jewish<br />

tradition’. Hebrew ideas about God’s marriage to or love of his<br />

chosen people are not only a parallel to but also a crucial source for<br />

Christian marriage symbolism. The reading of the Song of Songs<br />

adopted by the third-century Christian theologian Origen owed<br />

much to Jewish tradition, and Origen is a decisive influence on the<br />

whole subsequent tradition of Christian marriage symbolism (on<br />

the ‘Church as bride of Christ’ as well as on the ‘Soul as bride of<br />

Christ’ themes).<br />

Thus the Bernardine tradition of bridal mysticism has parallels in<br />

Hinduism, and the image of Christ’s marriage to the Church draws<br />

on Old Testament Judaism. What may be harder to find in other<br />

religious traditions is the sober rationality with which medieval<br />

scholastic writers and canon lawyers integrated marriage symbolism<br />

into their systematic and coherent religious frameworks. The<br />

Supplement to the Summa theologica of Thomas Aquinas succinctly<br />

integrates the di·erent levels into a coherent structure. Marriage<br />

is formed by signs of consent, usually verbal, not necessarily in a<br />

religious ceremony. These external signs represent a further level:<br />

the binding of man and woman. If the couple are Christians, this<br />

signifies and also brings about a spiritual union. This is the ‘sacrament’<br />

in the more technical theological sense, worked out by the<br />

time of Aquinas, of a sign of grace that brought about what it represented.<br />

Beyond that, there is another layer still. The spiritual<br />

union of man and woman represents, but does not bring about, the<br />

union of Christ and the Church. This dense symbolism from the<br />

tary, ed. R. E. Brown, J. A. Fitzmyer, and R. E. Murphy, i (London, 1968), 366–86<br />

at 377, on Isa. 50, with reference to Isa. 54: 6–8 and 61: 4–5.<br />

R. E. Murphy, ch. 30, ‘Canticle of Canticles’, ibid. 506–10 at 507.<br />

‘For Christian readings of the Song of Songs, especially as popularized by<br />

Origen, this assumption [that the “Old Testament” is reflected in the “New Testament”]<br />

automatically suggested the scope of prior meanings; that is, the poems read<br />

by Jews as the love between God and Israel naturally find their “true” sense as the<br />

love between Christ and the Church’ (E. A. Matter, The Voice of my Beloved: The<br />

Song of Songs in Western Medieval Christianity (Philadelphia, c.1990), 51).<br />

Supplementum, 42. 1, ‘Ad quartum’ and ‘Ad quintum’, 42. 2, ‘Respondeo’,<br />

and 42–3, ‘Respondeo’ and ‘Ad secundum’: see SanctiThomaeAquinatis...opera<br />

omnia, iussu . . . Leonis XIII P.M. edita, xii (Rome, 1906), 81–2. For the Supplement,<br />

put together after the death of Aquinas on the basis of his commentary on the<br />

Sentences of Peter the Lombard, see J. Weisheipl, Friar Thomas d’Aquino: His Life,

Introduction 9<br />

world of rational speculative scholastic theology is a far cry from<br />

the emotional outpourings of the Bernardine tradition.<br />

The parallelism between symbolic and literal can take one by<br />

surprise. The Summa theologica Supplement raises this objection:<br />

Sacraments have ecacy from the passion of Christ. But a person<br />

does not become conformed to the passion through marriage, which<br />

is accompanied by delight. Theansweristhatmarriageisconformed<br />

to the passion not through pain but through the love which<br />

Christ showed the Church by su·ering to unite her to himself as<br />

his bride.<br />

State of research<br />

Aquinas is one writer among many powerful minds who created a<br />

tradition of rationally analysing marriage symbolism. This tradition<br />

has been well studied, above all in a little-known but (for our<br />

Thought and Works (Oxford, 1974), 362. In his view the compilation ‘was, no doubt,<br />

the work of Thomas’s earliest editors working under the direction of Reginald of<br />

Piperno’. These passages are taken from Aquinas’s commentary on the Sentences<br />

of Peter Lombard at dist. 26, qu. 2, arts. 1–3 (see the concordance of Supplement<br />

and commentary in SanctiThomaeAquinatis...operaomnia, vol. xii, p. xxv, and<br />

S. Tommaso d’Aquino: Commento alle Sentenze di Pietro Lombardo e testo integrale<br />

di Pietro Lombardo. Libro quarto. Distinzioni 24–42. L’Ordine, il Matrimonio, trans.<br />

and ed. by ‘Redazione delle Edizioni Studio Domenicano’ (Bologna, 2001), 196–<br />

206. For Aquinas on marriage as a symbol of the union of Christ and the Church<br />

see R. J. Lawrence, The Sacramental Interpretation of Ephesians 5: 32 from Peter<br />

Lombard to the Council of Trent (The Catholic University of America Studies in<br />

Sacred Theology, Second Series, 145; Washington, 1963), 67–72. The whole of this<br />

work is relevant for the theological background it provides to the social history<br />

which is the main focus of this book. For another scholastic theologian’s marriage<br />

symbolism see Pierre de Tarantaise, commenting on Peter Lombard, Sentences,<br />

4, dist. 26, qu. 3: ‘Coniunctio exterius apparens per signa aliqua est sacramentum<br />

tantum: coniunctio animorum interior sacramentum et res: e·ectus gratiae quae ibi<br />

confertur, res non sacramentum: res inquantum primo significata, res vero significata<br />

secundario coniunctio Christi et Ecclesiae’ (Innocentii Quinti Pontificis Maximi ...<br />

In IV. librum Sententiarum commentaria, iv (Toulouse, 1651), 287).<br />

Cf. Summa theologica, 3. 62. 5 for the theology presupposed.<br />

Supplementum, 42. 1, obj. 3.<br />

Ibid., ‘ad tertium’ (objection and response are taken from Aquinas’s commentary<br />

on the Sentences of Peter Lombard: see Commento alle Sentenze di Pietro<br />

Lombardo . . ., trans. and ed. ‘Redazione delle Edizioni Studio Domenicano’, dist. 26,<br />

qu. 2, a. 1, pp. 196, 198). Cf. Pierre de Tarantaise: ‘Ad 4 de Passione. Resp. Christus<br />

est passus a}ictionem carnis ex charitate spirituali quam habebat ad Ecclesiam.<br />

Quoad primum, matrimonium non significabat passum, sed quoad secundum’ (Innocentii<br />

Quinti . . . commentaria, iv. 287). For the similar thinking in Ricardus de<br />

Mediavilla see T. Rinc‹on, El matrimonio, misterio y signo: siglos IX al XIII (Pamplona,<br />

1971), 319–20.

10 Introduction<br />

topic) fundamental book, Rinc‹on’s El matrimonio, mistero y signo.<br />

A main function of the present volume is to demonstrate the relevance<br />

of Rinc‹on’s findings to legal practice and social history.<br />

Rinc‹on prefers the word ‘Significac‹§on’ to symbolism. He wants<br />

to emphasize that the connection between human marriage and<br />

Christ’s union with the Church goes far beyond subjective ‘spiritual<br />

sense’-type parallelism. Though ‘symbolism’ will be used<br />

loosely to cover both kinds of meaning here, the distinction is worth<br />

bearing in mind: it reminds us that in theological texts marriage is<br />

linked to the union of Christ and the Church by a tight web of close<br />

logical reasoning. The same is true of canon-law commentaries,<br />

which Rinc‹on studies alongside the strictly theological texts.<br />

It is rash but important to generalize about world history: if the<br />

generalization is misleading, someone will point it out, but otherwise<br />

no one will know either way. I would suggest, then, that there<br />

is nothing in the world history of religions much like the developments<br />

Rinc‹on describes. If Rinc‹on has made an exemplary analysis<br />

of the theological and canon legal texts, marriage symbolism in literary<br />

and mystical texts has been the object of studies distinguished<br />

by literary sensitivity and a preoccupation with the paradoxes of a<br />

gendered symbolism which both men and women could in principle<br />

use for their relation to God. The bridal mysticism of Bernard of<br />

See n. 32 ad fin. I have not found this book in the British Library, Bodleian Library,<br />

or Cambridge University Library. There are copies in the Birmingham University<br />

Library, the Biblioth›eque Nationale de France, in several German libraries,<br />

and of course in Spain. More recently, see T. Rinc‹on-P‹erez [the same author, I<br />

take it], El matrimonio cristiano: sacramento de la Creaci‹on y de la Redenci‹on. Claves<br />

de un debate teol‹ogico-can‹onico (Estudios Can‹onicos, 1; Pamplona, 1997), chs. 1–3.<br />

For marriage symbolism in connection with sacramentality see also Lawrence, The<br />

Sacramental Interpretation of Ephesians 5: 32, which should in turn be bracketed<br />

with S. P. Heaney, The Development of the Sacramentality of Marriage from Anselm<br />

of Laon to Thomas Aquinas (The Catholic University of America Studies in Sacred<br />

Theology, Second Series, 134; Washington, 1963).<br />

‘Creemos fundamental distinguir entre simbolismo o paralelismo simb‹olico y<br />

significaci‹on come tal. Lo primero, en t‹erminos gramaticales, equivale a una simple<br />

yuxtaposici‹on del sentido m‹§stico y el sentido literal. Mientras que en la en la<br />

significaci‹on come tal existe un subordinaci‹on o dependencia profunda del signo en<br />

relaci‹on con la cosa significada’ (Rinc‹on, El matrimonio, misterio y signo, 270 n. 48).<br />

Thus N. Cartlidge, Medieval Marriage: Literary Approaches, 1100–1300<br />

(Cambridge etc., 1997), develops a persuasive argument that despite the exaltation<br />

of virginity over marriage in some of the texts he studies they still make marriage<br />

symbolize a ‘true drama of feeling’ and stand as ‘a paradigm of emotional commitment’;<br />

‘the sponsa Christi-motif is much more than a rhetorical metaphor for<br />

spiritual union: it is used to evoke a psychological process’ (159).<br />

e.g. Newman, From Virile Woman to WomanChrist: ‘If monks wished to play

Introduction 11<br />

Clairvaux has also been thoroughly examined. Perhaps a majority<br />

of the writers on all these topics have a background in literature<br />

or religious studies (defined to include theology and canon law).<br />

That is no defect: it has doubtless sharpened their perception of<br />

religious subtleties and nuances. The present study has a somewhat<br />

di·erent and complementary aspect because it comes from a historian<br />

formed in an age when the social history of marriage was the<br />

hottest of historiographical topics.<br />

Before the 1970s not much of the history of marriage was written<br />

from history departments. Excellent work was done by church<br />

lawyers: catholics like Esmein and Dauvillier, but also Protestants<br />

like Sohm and Friedberg, engaged in a controversy about<br />

the introduction of civil marriage into Prussia, whose resonances<br />

seem faint today. (The contribution of German Protestants to medi-<br />

the starring role in this love story, they had to adopt a feminine persona—as many<br />

did—to pursue a heterosexual love a·air with their God. It might be assumed that<br />

when women began to compose their own mystical texts, they could more easily<br />

havefollowedthepathalreadylaidoutbymen.But...somewomenforgeda...<br />

less stereotypical way that allowed them a wider emotional range’, adopting the<br />

discourse of fin amour which ‘could encourage women writers to experiment with<br />

gender roles just as monks did within the Song of Songs tradition’ (138). (C. W.<br />

Bynum is almost certainly an inspiration behind this kind of analysis: see e.g. her<br />

‘“And Woman his Humanity”: Female Imagery in the Religious Writings of the<br />

Later Middle Ages’, in Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the<br />

Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York, 1991), 151–79 at 176–9.) Or again<br />

Keller, My Secret is Mine: ‘Bernard of Clairvaux’s e·orts to re-establish the bridal<br />

metaphor in the monastic life of both sexes mark precisely the beginning of the<br />

definitive exclusion of monks from the concept’ (35); ‘Precisely the history of the<br />

motif of the bride of God itself, both its gender-specific fixing of the role of the bride<br />

of God and its attempts to force open such narrowings make clear that the human<br />

world of the sexes and its historically-determined mechanisms push their way into<br />

spiritual eroticism by the back door’ (263). Keller’s bibliography is a good guide<br />

to recent literature on marriage/bridal symbolism. For an exemplary analysis of<br />

gender in marriage symbolism see A. Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval<br />

German Writing: Imitating the Inimitable (Oxford, 2001), 138–60.<br />

J. Leclercq, Le Mariage vu par les moines au XIIe si›ecle (Paris, 1983), ch. 7, is an<br />

especially important study. See too his Monks and Love in Twelfth-Century France:<br />

Psycho-Historical Essays (Oxford, 1979).<br />

A. Esmein, Le Mariage en droit canonique ed. R. G‹enestal and J. Dauvillier, 2nd<br />

edn. (2 vols.; Paris, 1929–35).<br />

J. Dauvillier, Le Mariage dans le droit classique de l’‹eglise depuis le D‹ecret de<br />

Gratien (1140) jusqu’›a lamortdeCl‹ement V (1314) (Paris, 1933).<br />

R. Sohm, Das Recht der Eheschlie¢ung aus dem deutschen und kanonischen Recht<br />

geschichtlich entwickelt: Eine Antwort auf die Frage nach dem Verh•altniss der kirchlichen<br />

Trauung zur Civilehe (Weimar, 1875).<br />

E. Friedberg, Verlobung und Trauung, zugleich als Kritik von Sohm: Das Recht<br />

der Eheschlie¢ung (Leipzig, 1876).

12 Introduction<br />

eval canon-law history would be an interesting topic.) The great<br />

Gabriel Le Bras defies classification: he was somewhere between<br />

law, theology and sociology: a great historian by nature but not<br />

by formal training. Joyce, a theologian, wrote a fine synthesis,<br />

and the German school of Catholic medieval historical theology,<br />

notably M•uller, Brandl, and Ziegler, also made contributions<br />

which have lost little of their value today. Still, they were not writing<br />

primarily for a community of historians and, perhaps more important,<br />

they wrote at a time when social history had not attained the<br />

dominance it enjoyed in the last decades of the twentieth century.<br />

Non-historians have continued to contribute even in those decades.<br />

Goody, who raised with great intelligence even if he did<br />

not solve the historical problem of the ‘forbidden degrees’, came<br />

from anthropology; Gaudemet, Weigand, Helmholz, and Donahue<br />

were again from law; Jean Leclercq, though clearly a<br />

historian in his attitudes and approach and with his finger on the<br />

See especially his article on ‘Mariage. III. La doctrine du mariage chez les<br />

th‹eologiens et canonistes depuis l’an mille’, in Dictionnaire de th‹eologie catholique<br />

(15 vols. excluding indexes; Paris, 1899–1950), ix (1926), 2123–223.<br />

G. H. Joyce, Christian Marriage: An Historical and Doctrinal Study (London<br />

etc., 1933).<br />

M. M•uller, Die Lehre des hl. Augustinus von der Paradiesesehe und ihre Auswirkung<br />

in der Sexualethik des 12. und 13. Jahrhunderts bis Thomas von Aquin:<br />

Eine moralgeschichtliche Untersuchung (Studien zur Geschichte der katholischen<br />

Moraltheologie, 1; Regensburg, 1954).<br />

L. Brandl, Die Sexualethik des heiligen Albertus Magnus (Regensburg, 1955).<br />

J. G. Ziegler, Die Ehelehre der P•onitentialsummen von 1200–1350: Eine Untersuchung<br />

zur Geschichte der Moral- und Pastoraltheologie (Regensburg, 1956).<br />

J. Goody, The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe (Cambridge,<br />

1983). This has received a fair amount of criticism though there has been a general<br />

appreciation too of the way the book has opened up the subject. For my own critiques<br />

see ‘Peter Damian, Consanguinity and Church Property’, in L. Smith and B. Ward<br />

(eds.), Intellectual Life in the Middle Ages: Essays Presented to Margaret Gibson<br />

(London, 1992), 71–80 at 76–7, and ‘Lay Kinship Solidarity and Papal Law’, in P.<br />

Sta·ord, J. L. Nelson, and J. Martindale (eds.), Law, Laity and Solidarities: Essays<br />

in Honour of Susan Reynolds (Manchester, 2001), 188–99.<br />

J. Gaudemet, Le Mariage en Occident: les m¥urs et le droit (Paris, 1987), to<br />

name only one of his contributions.<br />

R. Weigand, Liebe und Ehe im Mittelalter (Bibliotheca Eruditorum, 7; Goldbach,<br />

1993).<br />

R. H. Helmholz, Marriage Litigation in Medieval England (Cambridge, 1974).<br />

C. Donahue, Jr., ‘The Monastic Judge: Social Practice, Formal Rule, and the<br />

Medieval Canon Law of Incest’, in P. Landau, with M. Petzolt (eds.), De iure<br />

canonico medii aevi: Festschrift f•ur Rudolf Weigand (Studia Gratiana, 27; Rome,<br />

1996), 49–69; (with Norma Adams), Select Cases from the Ecclesiastical Courts of the<br />

Province of Canterbury, c. 1200–1301 (Selden Society, 95; London, 1981).<br />

See above, n. 37.

Introduction 13<br />

pulse of his time’s historiography, was writing from a monastery<br />

rather than a history department. Hubertus Lutterbach comes from<br />

theology. Students of vernacular literature like Schumacher and<br />

Burch have done thought-provoking work. Cartlidge’s study,<br />

mentioned above under the rubric of symbolic marriage, talks<br />

about perceptions of real human marriage as well. Perhaps the<br />

most important recent historian of medieval marriage and sexuality,<br />

R•udiger Schnell holds his chair in a department of Germanistik,<br />

though he has mastered the bibliography in all medieval<br />

fields on these topics to an astonishing degree. Only the historian<br />

Brundage, on whom below, can come near him as a guide to this<br />

practically endless sea of secondary scholarship.<br />

Brundage is one of a substantial number of historians employed<br />

in history departments who have added to this tower of scholarship<br />

recently, holding their own with colleagues from other sectors of<br />

academe. They are not necessarily more impartial—indeed, in this<br />

field historians tend to make their ideological aliations as evident<br />

as historians of monasticism used to before the First World War.<br />

Moreover, some have continued to use the same types of evidence as<br />

scholars from other disciplines: Payer’s The Bridling of Desire is<br />

in the tradition of historical theology and Brundage’s opus magnum<br />

is based above all on penitentials and canon-law commentaries so<br />

far as primary sources are concerned, although, as just noted, he<br />

is remarkably successful in getting a grip on the enormous mass<br />

H. Lutterbach, Sexualit•at im Mittelalter: Eine Kulturstudie anhand von Bu¢b•uchern<br />

des 6. bis 12. Jahrhunderts (Cologne etc., 1999). Although the style is detached,<br />

there are signs that he is himself fighting a battle within the world of Catholic<br />

theology.<br />

M. Schumacher, Die Auffassung der Ehe in den Dichtungen Wolframs von Eschenbach<br />

(Germanische Bibliothek, 2. Abt., Untersuchungen und Texte, 3. Reihe,<br />

Untersuchungen und Einzeldarstellungen; Heidelberg, 1967).<br />

S. L. Burch, ‘A Study of Some Aspects of Marriage as Presented in Selected<br />

Octosyllabic French Romances of the 12th and 13th Centuries’ (unpublished Ph.D.<br />

thesis, University College London, 1982).<br />

See above all R. Schnell, Sexualit•at und Emotionalit•at in der vormodernen Ehe<br />

(Cologne etc., 2002).<br />

Theopus magnum is J. A. Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval<br />

Europe (Chicago etc., 1987). Brundage’s publications on medieval marriage and sex<br />

are too numerous to list here, but special mention must be made of his ‘The Merry<br />

Widow’s Serious Sister: Remarriage in Classical Canon Law’, in R. R. Edward and<br />

V. Ziegler (eds.), Matrons and Marginal Women in Medieval Society (Woodbridge,<br />

1995), 33–48, which is directly relevant to Chapter 3.<br />

P. J. Payer, The Bridling of Desire: Views of Sex in the Later Middle Ages<br />

(Toronto etc., 1993).

14 Introduction<br />

of secondary scholarship about medieval marriage in three or four<br />

academic languages. Conversely, the analyses of actual court records<br />

by Weigand and Helmholz take us firmly beyond the world of ‘book<br />

texts’, if one may so put it. By and large, however, the professional<br />

historians have helped to root the subject more firmly in social<br />

history—converging with some of the lawyers in this respect.<br />

Christopher Brooke was very early in the field, including sections<br />

on marriage in a general survey, a historian somewhat ahead<br />

of his time. In a series of subsequent publications, he brought to<br />

bear on the history of marriage a knowledge of central medieval<br />

social history that owed much to his involvement with the Oxford<br />

Medieval Texts editorial project. The present study takes up a<br />

question that he put more clearly than any of the other historians<br />

who made up the wave of writing on medieval marriage: namely,<br />

what was di·erent about the Christian marriage of the Middle<br />

Ages? The Christianization of marriage in the twelfth century has<br />

been a central thread. Georges Duby used his remarkable architectonic<br />

literary gifts to develop an elegant and still broadly valid<br />

schema: an aristocratic model, favouring legitimate marriage but allowing<br />

easy divorce, and tolerating the marriage of close relatives,<br />

opposed to a clerical model emphasizing indissoluble monogamous<br />

marriage—exogamy. The endogamy/exogamy part of the thesis<br />

requires further commentary out of place in this argument, but<br />

the notion that the two models grew closer together in the early<br />

thirteenth century is broadly right. The lay nobility came to accept<br />

indissolubility, and the Church reduced the circle of forbidden<br />

degrees of relationship, allowing closer relatives to marry. All this<br />

needs to be put in the context of a rationality perhaps not fully<br />

understood by Duby. It should also be noted that he was able to<br />

draw on some crucial discoveries made earlier by John Baldwin<br />

about the thinking behind the changes in marriage law e·ected<br />

by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. In general Duby’s work<br />

tends to leave the impression that the medieval Church took a nega-<br />

C. N. L. Brooke, Europe in the Central Middle Ages 962–1154 (London, 1964;<br />

3rd edn. Harlow, 2000): in first edition 245–7 and index s.v. ‘Marriage’.<br />

His results were drawn together in The Medieval Idea of Marriage (Oxford,<br />

1989), still probably the best way into the subject.<br />

Duby, Medieval Marriage; id.,Le Chevalier, la femme et le pr^etre: le mariage<br />

dans la France f‹eodale (Paris, 1981).<br />

J. W. Baldwin, Masters, Princes, and Merchants: The Social Views of Peter the<br />

Chanter and his Circle (2 vols.; Princeton, 1970), i. 332–7, ii. 222–7 (classic pages).

Introduction 15<br />

tive view of marriage, a view corrected in friendly fashion by Jean<br />

Leclercq (and as we shall see quite contrary to copious evidence<br />

of which he was unaware). Dyan Elliott’s study of ‘Spiritual Marriage’<br />

(understood not in the usual sense of symbolic marriage but<br />

as marriage without sex) used saints’ lives alongside theological and<br />

canon-law texts, and tried to reconstruct actual practices. David<br />

Herlihy traced the change from an early medieval society where<br />

the rich and powerful had more than their fair share of women to a<br />

society where the husband-and-wife couple was the norm at all levels<br />

of society: the slimness of his Medieval Households is in inverse<br />

proportion to its achievement. Michael Borgolte has set the medieval<br />

Church’s e·orts to enforce monogamy and indissolubility in a<br />

comparative framework by showing how its sphere of influence was<br />

ringed with an outer sphere of polygyny, among the Muslims and<br />

Jews outside the borders of Latin Europe but also among Christians<br />

who came in contact with them or who maintained a polygynous<br />

subculture.<br />

The general trend of most recent work has been to emphasize the<br />

growing though always limited influence of the Church’s models<br />

on the social history of marriage (indeed, Borgolte emphasizes it<br />

too). This is particularly but not exclusively true of the work by<br />

scholars in history departments. This study will draw heavily on<br />

their results, especially the findings of scholars who have studied<br />

ecclesiastical court evidence.<br />

The argument<br />

The specific aim of the present study is to draw together the social<br />

history of marriage and the history of marriage symbolism. I<br />

am not quite the first historian to have seen the connection, for<br />

D. Elliott, Spiritual Marriage: Sexual Abstinence in Medieval Wedlock (Princeton,<br />

1993). Her use of ‘spiritual marriage’ to mean marriage without sex is perhaps<br />

confusing since the phrase often means marriage as metaphor, but there is a pedigree<br />

behind her terminology: see P. de Labriolle, ‘Le “mariage spirituel” dans l’antiquit‹e<br />

chr‹etienne’, Revue historique, 137 (1921), 204–25.<br />

D. Herlihy, Medieval Households (Cambridge, Mass., etc., 1985).<br />

M. Borgolte, ‘Kulturelle Einheit und religi•ose Di·erenz: Zur Verbreitung<br />

der Polygynie im mittelalterlichen Europa’, Zeitschrift f•ur historische Forschung,<br />

31 (2004), 1–36; for aristocratic polygyny in regions or cultures within Christian<br />

Europe see ibid. 7 n. 23 from p. 6 (referring to the work of Jan R•udiger).<br />

Ibid. 11, 13.<br />

As an example see the able survey by D. O. Hughes, ‘Il matrimonio nell’Italia<br />

medievale’, in M. De Giorgio and C. Klapisch-Zuber (eds.), Storia del matrimonio<br />

(Rome etc., 1996), 5–61, notably 18–24, 44–9.

16 Introduction<br />

I think that Marcel Pacaut caught the essence of it in a few perceptive<br />

lines. Most of the actual links of causation need to be traced.<br />

This enterprise is related to the skilful elucidations by canon-law<br />

historians of marriage symbolism’s influence on the idea of the<br />

episcopal oce, to Dye’s important study of Marian marriage<br />

In a brief article that anticipates more than any other study the general approach<br />

of this book, Pacaut develops with respect to the twelfth century an argument that<br />

works even better for the mid-thirteenth century and after. To do justice to his<br />

priority a full quotation is required:<br />

le renvoi du couple Christ- ‹Eglise . . . tend aussi ›a exposer que le Christ et l’ ‹Eglise<br />

—et de m^emeleChristetl’^ame — sont uns comme le sont l’‹epoux et l’‹epouse<br />

dans leur union charnelle, ainsi que le sugg›ere Pierre Lombard, ce qui se rapporte<br />

›a une image claire et simple selon laquelle l’union des corps est d’autant plus<br />

parfaite qu’elle repose sur l’amour et ce qui revient ›a rapprocher un mod›ele (pour<br />

l’^ame) et une r‹ealit‹e dicile ›a saisir (pour l’ ‹Eglise) d’un autre mod›ele facilement<br />

concevable, presque “visualis‹e” et non utopique, car il existait certainement. C’est<br />

l›a aussi le sens profond de la m‹etaphore reprise dans les sermons sur le Cantique<br />

des Cantiques, qui ne peuvent exclure l’appel ›alar‹ealit‹e charnelle, et dont on peut<br />

tirer parfois, ›a l’inverse, qu’il serait souhaitable que les ‹epoux soient unis comme<br />

le Christ l’est avec son ‹Eglise.<br />

Ces propos ressortissent en fait ›a une m‹editation mystique et sont en m^eme<br />

temps le reflet de la pastorale di·us‹ee par le clerg‹e. Celle-ci insiste sur la valeur<br />

de l’amour conjugal et sur sa n‹ecessit‹e pour accomplir le mariage par le moyen de<br />

l’union des corps. Elle souligne que le consentement, qui fait que l’union charnelle<br />

n’est pas honteuse, oriente les vies vers l’amour. Elle atteste donc aussi de ce qu’un<br />

e·ort s’accomplit alors afin que la r‹eussite amoureuse, physique et sentimentale,<br />

soit facilit‹ee par l’engagement consensuel reconnu, ›al’‹epoque o›u le droit cherche,<br />

sur une autre voie, ›a normaliser cet engagement, sans lequel la pr‹edication et<br />

la r‹eflexion spirituelle ne reposeraient, dans leur ‹elaboration, sur aucun support<br />

solide. (‘Sur quelques donn‹ees du droit matrimonial dans la seconde moiti‹e du<br />

xiiE si›ecle’, in Histoire et soci‹et‹e: m‹elanges o·erts ›a Georges Duby. Textes r‹eunis<br />

par les m‹edi‹evistes de l’Universit‹e deProvence(2 vols.; Aix-en-Provence, 1992), i.<br />

31–41 at 40)<br />

Keller, My Secret is Mine, especially chapter 2, also explores the interplay between<br />

symbolism and social practice. Her findings are very di·erent (without being<br />

necessarily incompatible), because she concentrates on social practices which<br />

are ‘Firmly rooted in the tradition of Germanic Law’ (p. 69)—Muntehe etc.—<br />

rather than the social structure created in the high and late Middle Ages by canon<br />

law. I. Persson, Ehe und Zeichen: Studien zu Eheschlie¢ung und Ehepraxis anhand<br />

der fr•uhmittelhochdeutschen religi•osen Lehrdichtungen ‘Vom Rechte’, ‘Hochzeit’ und<br />

‘Schopf von dem l^one’ (G•oppinger Arbeiten zur Germanistik, 617; G•oppingen, 1995),<br />

takes a close look at the relation between the details of marriage in poetic allegory and<br />

legal notions of marriage: see notably pp. 127–8. I am in sympathy with the approach<br />

but the contrast she draws between the Germanic and the canon-law attitudes to<br />

consummation may be overstated: see below, ch. 4 n. 16.<br />

S. Kuttner, ‘Pope Lucius III and the Bigamous Archbishop of Palermo’ (1961),<br />

repr. in id., The History of Ideas and Doctrines of Canon Law in the Middle Ages<br />

(London, 1980), no. vii; R.L.Benson,The Bishop Elect: A Study in Medieval<br />

Ecclesiastical Oce (Princeton, 1968), 122–9, 136–49; J. Gaudemet, ‘Le symbolisme<br />

du mariage entre l’‹ev^eque et son ‹eglise et ses consequences juridiques’ (1985), repr.

Introduction 17<br />

symbolism, and to Gabriella Zarri’s remarkable account of marriage<br />

symbolism in rituals and iconography. It is nevertheless a<br />

quite distinct line of enquiry.<br />

There will be a lot of thick description of the symbolic forms<br />

of thought underlying marriage law and practice, but the book<br />

has preoccupations which are rather played down in anthropology<br />

›a laCli·ord Geertz (which sees the study of society as more like<br />

interpreting a poem than causal analysis): force (not necessarily in a<br />

negative sense) and timing. In a nutshell, I shall try to establish how,<br />

when, and why marriage symbolism became a force in the lay world.<br />

Stated baldly, the line of interpretation goes like this. Marriage is<br />

a powerful symbol of the union of the human and the divine. Most<br />

relationships are superficial compared with marriage. Marriage is<br />

one of the strongest experiences in many people’s lives. Comparison<br />

with marriage is a way of conveying the strength of the bond<br />

between God and humanity. Marriage has many dimensions which<br />

can be explored to bring out by analogy aspects of union with God.<br />

A symbol or metaphor is capable of generating new ideas about<br />

the relationship it describes, whether that relationship is real or<br />

imaginary. It can also a·ect social policy and structures. Marriage<br />

is a ‘generative’ metaphor, vivid, full of unexpected possibilities,<br />

potentially a powerful influence on thought and action. (Not all<br />

metaphors are like this. Many have limited use and quickly become<br />

desiccated, like the ‘man is a wolf’ formula beloved of philosophers<br />

who discuss metaphor.) Other powerful generative metaphors are<br />

the meal as a symbol of community, the body as a symbol of the<br />

state, or the ‘conduit’ metaphor for communication.<br />

in id., Droit de l’ ‹Eglise et vie sociale au Moyen ^Age (Northampton, 1989), no. ix,<br />

110–23.<br />

J. M. Dye, ‘The Virgin as Sponsa c.1100–c.1400’ (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,<br />

University College London, 2001).<br />

G. Zarri, Recinti: donne, clausura e matrimonio nella prima et›a moderna([Bologna],<br />

2000), ch. 4. It deals (to quote a summary earlier in the same book) especially<br />

with the ‘pratica medievale di matrimoni simbolici, che aveva lo scopo, tra l’altro, di<br />

confermare la sacralit›a del matrimonio cristiano, in assenza di una ritualit›a religiosa<br />

pubblica nel matrimonio della coppia celebrato prevalentemente tra le mura domestiche’<br />

(26). I share Zarri’s preoccupation with the connections between symbolism<br />

and social practices.<br />

D. A. Sch•on, ‘’Generative Metaphor: A Perspective on Problem-Setting in<br />

Social Policy’, in A. Ortony (ed.), Metaphor and Thought (Cambridge, 1979), 254–<br />

83.<br />

M. J. Reddy, ‘The Conduit Metaphor: A Case of Frame Conflict in our Language<br />

about Language’, in Ortony (ed.), Metaphor and Thought, 284–324.

18 Introduction<br />

It will be argued that marriage symbolism had a quite limited<br />

causal impact for much of the Middle Ages: up until the long century<br />

around the year 1200. Therefore the explanations advanced<br />

in this book will often take the form of elucidating ‘neutralizing<br />

causes’, forces that neutralize a causal process which might otherwise<br />

be expected. I shall attempt to explain what prevented marriage<br />

symbolism for so long from becoming a force in the lay world.<br />

From the thirteenth century on it was indeed a force and changed<br />

social patterns.

1<br />

Mass Communication<br />

(a) Preliminaries<br />

The bulk of this book deals with the e·ect of marriage symbolism<br />

outside the texts that transmitted it. Much of the discussion is<br />

about the changes it brought about through law in social practice,<br />

but a natural starting point is its power over the minds of the<br />

laity through the cumulative force of mass communication. The<br />

argument of the present chapter makes the assumption that the<br />

cumulative repetition of much the same message by a powerful<br />

mass medium does have an e·ect on the thoughts of the people<br />

at the receiving end. It is an assumption. Some feel that the mass<br />

media do not really change people’s thinking at all. They may be<br />

right with regard to short-term propaganda. Brief intense political<br />

campaigns or revivalist preaching may well have a transitory impact<br />

and no lasting e·ect on attitudes. Can the same be true of ideas<br />

repeated over years and decades? Ideas propagated over a long<br />

period of time by modern newspapers (for instance) surely leave<br />

some mark on the minds of readers, as a dripping tap leaves a stain<br />

in a sink. As with modern newspapers, there is little hard empirical<br />

evidence at the reception end. Could one establish with absolute<br />

certainty the e·ect of newspapers on a single reader? Paradoxically,<br />

one can be more confident about aggregate e·ects. Ideas repeated<br />

to great masses of people over many decades will have impinged in<br />

some way on the minds of a significant portion of the audience: this<br />

much is taken for granted. The whole argument of this chapter is<br />

vulnerable to extreme scepticism on this point, but such scepticism<br />

flies in the face of common sense. The question then becomes one<br />

of timing and scale: when did marriage symbolism become such a<br />

regular part of preaching that laypeople who went to sermons could<br />

hardly escape it? It will be answered as follows:<br />

D. L. d’Avray, Medieval Marriage Sermons: Mass Communication in a Culture<br />

without Print (Oxford, 2001), 14.

20 Chapter 1<br />

å Marriage symbolism was not preached to a mass public in the<br />

early Middle Ages. The influential collections containing marriage<br />

symbolism were not intended for popular preaching, the<br />

many surviving sermons intended for popular preaching contain<br />

relatively little marriage symbolism, and the impact of<br />

marriage symbolism would have been limited by extra-textual<br />

factors (late development of the parish system, incapacity of<br />

many priests to use Latin models e·ectively).<br />

å Preaching was a system of mass communication in the age of<br />

the friars. The large number of surviving manuscripts of model<br />

sermons represents a tiny proportion of the number that once<br />

existed, and each model sermon could be preached again and<br />

again.<br />

å Marriage symbolism is highly developed in late medieval<br />

preaching and rested securely on a literal-sense idea of marriage<br />

as good and holy. The symbolism of marriage and the<br />

praise of ordinary human marriage were complementary and<br />

are found together in the sermons that transmitted marriage<br />

symbolism to the masses.<br />

The middle section on preaching as mass communication and the<br />

long discussion of the loss rate of preaching manuscripts and of<br />

how so many could have been produced in the first place is the key<br />

to the argument that in the age of the Franciscans and Dominicans<br />

marriage symbolism was propagated so insistently and repeatedly<br />

to so many people that it must have been a social force. Some of<br />

the people could have ignored it all of the time and all of the people<br />

surely ignored it much of the time, but all of the people could not<br />

have ignored it all of the time.<br />

(b) The Early Middle Ages<br />

Bernard of Clairvaux and Haymo of Auxerre<br />

Marriage symbolism in preaching is associated with the sermons<br />

on the Song of Songs by Bernard of Clairvaux, but in fact it can<br />

be found long before, though in a more sober idiom. A ninthcentury<br />

homily by Haymo of Auxerre has, at least embryonically,<br />

the main features of the genre of sermons on the second Sunday<br />

On Haymo/Haimo see B. Gansweidt, ‘Haimo. 1. Haimo v. Auxerre’, in Lexikon<br />

des Mittelalters, iv (Munich etc., 1989), 1863; on the homily see D. L. d’Avray, ‘Sym-

Mass Communication 21<br />

after Epiphany (mostly sermons on the text Nuptiae factae sunt,<br />

John 2: 1) that would be the principal vehicle for marriage preaching<br />

in future centuries. Marriage is good. Christ’s presence at a<br />

wedding refutes heretics who condemn marriage. (He mentions<br />

Tatian and Marcion: later preachers would have the Cathars in<br />

mind.) Genesis proves that God created man male and female,<br />

and said that for the love of her husband a woman should leave<br />

father and mother and be one flesh with her husband. In Matthew<br />

Christ told the apostles that a husband must not leave his wife.<br />

Teachings of St Paul take their turn: husband and wife must pay<br />

the marriage ‘debt’ (make love at the other’s request). Husbands<br />

should love their wives as Christ loved his Church. In fact Haymo<br />

makes a good florilegium of biblical texts which are positive about<br />

marriage—ordinary human marriage. Then he goes on to the marriage<br />

of Christ and the Church, again presented through scriptural<br />

authorities. This combination of literal and spiritual (i.e. symbolic)<br />

marriage within the same framework is characteristic of the later<br />

‘Marriage feast of Cana’ genre of sermons on the second Sunday<br />

after Epiphany. (From here on this genre will also be called the<br />

Nuptiae factae sunt genre, the Latin for the first words of the reading<br />

‘There was a marriage . . .’.) The question remains, did this<br />

kind of marriage symbolism get through to the laity via popular<br />

preaching in the early Middle Ages? It is a hard question to answer.<br />

That will be apparent from the oscillations in the presentation of<br />

the data below. On balance, however, and in the current state of the<br />

evidence, it looks as though marriage symbolism in sermons could<br />

not have had a major impact on the laity before the thirteenth century.<br />

The debate about early medieval popular preaching<br />

It is much disputed whether popular preaching happened at all<br />

in this period (defined roughly as from the late sixth to the late<br />

twelfth century). A relatively recent article argues for a minimalist<br />

position: hardly any preaching. That rather extreme position<br />

seems hard to maintain in the light of work by Thomas Amos,<br />

who seems to have shown that there was a good deal of popu-<br />

bolism and Medieval Religious Thought’, in P. Linehan and J. L. Nelson (eds.), The<br />

Medieval World (London etc., 2003), 267–78 at 268–9.<br />

R. E. McLaughlin, ‘The Word Eclipsed: Preaching in the Early Middle Ages’,<br />

Traditio, 46 (1991), 77–122.

22 Chapter 1<br />

lar preaching. (He concentrates on the Carolingian period, but<br />

casts an eye back to earlier preaching.) His doctoral thesis on early<br />

medieval preaching unfortunately remains unpublished, but some<br />

of the findings have appeared in print as articles. He has identified<br />

‘over nine hundred sermons written or adapted by Carolingian<br />

authors as sources of popular preaching in the period<br />

750–950’. One collection has been properly edited in a modern<br />

edition: I shall refer to this by the name of its editor, Mercier.<br />

Three more are in Migne’s Patrologia Latina and easy to consult.<br />

Other popular Carolingian homiliaries have been studied in<br />

articles by three specialists whose work has changed our understanding<br />

of homiliaries: Barr‹e, Bouhot, and ‹Etaix. Yet another<br />

article argues that the homilies on the Gospels of Gregory the<br />

Great were widely used for popular preaching in the early Middle<br />

Ages.<br />

Marriage symbolism in early medieval popular preaching: a<br />

significant absence<br />

This is not sucient to show that marriage symbolism reached the<br />

people via the pulpit. We still need to ask how regularly marriage<br />

symbolism appeared in these sermons, and how many ordinary<br />

priests actually used the sermons Amos has studied. Even assuming<br />

that a non-trivial number of priests had reasonable Latin and<br />

a homiliary of the right level for their needs, a problem to which<br />

we must return, how much about marriage and marriage symbolism<br />

would it contain? My provisional verdict is that there was<br />

relatively little preaching about marriage symbolism in the Carolingian<br />

period. This is based mainly on a search for sermons on<br />

the Gospel reading of the marriage feast of Cana, which would<br />

‘The Origin and Nature of the Carolingian Sermon’ (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,<br />

Michigan State University, 1983). I have used this important thesis extensively:<br />

it led me to most of those sermons/homiliaries discussed below which Amos<br />

does not discuss in print.<br />

T. L. Amos, ‘Preaching and the Sermon in the Carolingian World’, in T. L.<br />

Amos, E. A. Green, and B. M. Kienzle (eds.), De ore Domini: Preacher and Word in<br />

the Middle Ages (Kalamazoo, 1989), 41–60 at 47.<br />

XIV hom‹elies du IXe si›ecle de l’Italie du Nord, ed. P. Mercier (Sources chr‹etiennes,<br />

161; Paris, 1970).<br />

Amos, ‘Preaching and the Sermon in the Carolingian World’, 57 n. 31, for<br />

bibliography.<br />

P. A. DeLeeuw, ‘Gregory the Great’s “Homilies on the Gospels” in the Early<br />

Middle Ages’, Studi medievali, 3rd ser., 26 (1985), 855–69.

Mass Communication 23<br />

be a powerful vehicle for the popularization of marriage symbolism<br />

from the thirteenth century on. In the last three medieval<br />

centuries sermons on this reading or ‘pericope’ would combine<br />

a real appreciation of marriage as a human institution with welldeveloped<br />

symbolism. Arguably, it was this complementarity of<br />

literal and symbolic levels that gave the symbolism its force. It is<br />

conceivable that early medieval marriage symbolism was expressed<br />

through some other preaching genre—say sermons on a di·erent<br />

pericope—but it is unlikely. I have probably missed a few marriage<br />