You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà<br />

yanko_slava@yahoo.com || http://yanko.lib.ru/ | http://www.chat.ru/~yankos/ya.html | Icq# 75088656<br />

update 6/17/01<br />

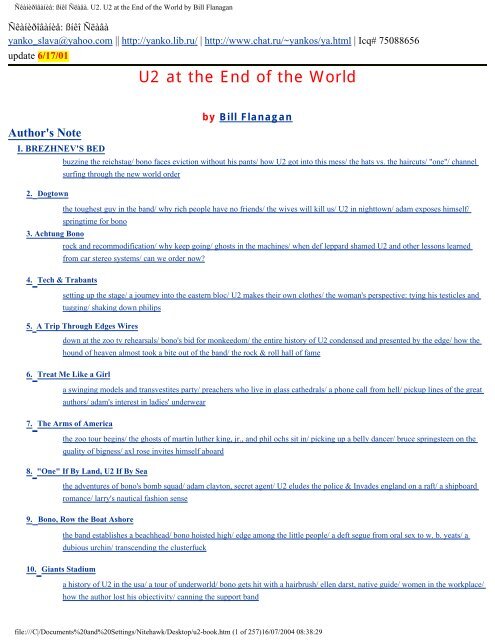

Author's Note<br />

I. BREZHNEV'S BED<br />

2. Dogtown<br />

3. Achtung Bono<br />

<strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World<br />

by Bill Flanagan<br />

buzzing the reichstag/ bono faces eviction without his pants/ how <strong>U2</strong> got into this mess/ the hats vs. the haircuts/ "one"/ channel<br />

surfing through the new world order<br />

the toughest guy in the band/ why rich people have no friends/ the wives will kill us/ <strong>U2</strong> in nighttown/ adam exposes himself/<br />

springtime for bono<br />

4. Tech & Trabants<br />

rock and recommodification/ why keep going/ ghosts in the machines/ when def leppard shamed <strong>U2</strong> and other lessons learned<br />

from car stereo systems/ can we order now?<br />

setting up the stage/ a journey into the eastern bloc/ <strong>U2</strong> makes their own clothes/ the woman's perspective: tying his testicles and<br />

tugging/ shaking down philips<br />

5. A Trip Through Edges Wires<br />

down at the zoo tv rehearsals/ bono's bid for monkeedom/ the entire history <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> condensed and presented by the edge/ how the<br />

hound <strong>of</strong> heaven almost took a bite out <strong>of</strong> the band/ the rock & roll hall <strong>of</strong> fame<br />

6. Treat Me Like a Girl<br />

a swinging models and transvestites party/ preachers who live in glass cathedrals/ a phone call from hell/ pickup lines <strong>of</strong> the great<br />

authors/ adam's interest in ladies' underwear<br />

7. The Arms <strong>of</strong> America<br />

the zoo tour begins/ the ghosts <strong>of</strong> martin luther king, jr., and phil ochs sit in/ picking up a belly dancer/ bruce springsteen on the<br />

quality <strong>of</strong> bigness/ axl rose invites himself aboard<br />

8. "One" <strong>If</strong> <strong>By</strong> <strong>Land</strong>, <strong>U2</strong> <strong>If</strong> <strong>By</strong> <strong>Sea</strong><br />

the adventures <strong>of</strong> bono's bomb squad/ adam clayton, secret agent/ <strong>U2</strong> eludes the police & Invades england on a raft/ a shipboard<br />

romance/ larry's nautical fashion sense<br />

9. Bono, Row the Boat Ashore<br />

10. Giants Stadium<br />

the band establishes a beachhead/ bono hoisted high/ edge among the little people/ a deft segue from oral sex to w. b. yeats/ a<br />

dubious urchin/ transcending the clusterfuck<br />

a history <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> in the usa/ a tour <strong>of</strong> underworld/ bono gets hit with a hairbrush/ ellen darst, native guide/ women in the workplace/<br />

how the author lost his objectivity/ canning the support band<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (1 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

II. PROMISE IN THE YEAR OF ELECTION<br />

12. Vegas<br />

a call from the governor <strong>of</strong> arkansas/ the same mistake made by henry ii/ the search for bono by the secret service/ two shots <strong>of</strong><br />

happy/ a setback for irish immigration/ george b. insults b. george/ the blood in the ground cries out for vengeance<br />

hangin' with the chairman/ goin' to the prizefights/ ridin' in white limos/ swingin' with the lord mayor/ bikin' in hotel rooms/<br />

feelin' like a sex machine<br />

13. Harps Over Hollywood<br />

bono does a movie deal/ shooting with william burroughs/ oldman out the back door, winona in the front/ phil joanou takes his<br />

lumps/ coitus interruptus in the editing room<br />

14. The Last Tycoon<br />

jumping <strong>of</strong>f the million-dollar hotel/ an existential moment in a war zone/ t-bone searches I.a. for his breakfast/ me/ gibson says<br />

nothing/ beep confounds the establishment/ the security system is tested<br />

15. The Conquest <strong>of</strong> Mexico<br />

16. Border Radio<br />

17. Home Fires<br />

bono and edge perplexed by the channel changer/ larry resents his bikes & babes image/ the hidden kingdom/ the power brokers<br />

appear/ love among the latins/ every limo a getaway car<br />

the arena catches fire/ dignitaries' daughters are presented to the band/ a trip to the purported red-light district/ who is the new<br />

rolling stones with commentary by mr. jagger/ <strong>U2</strong> among the jews<br />

<strong>U2</strong> insults phil c<strong>of</strong>fins and their parents/ the origins <strong>of</strong> adam/ spearing the penultimate potato/ the virgin prunes reunite without<br />

instruments/ legends <strong>of</strong> mannix/ an audience with edge's ancestors<br />

18. The Saints Are Coming Through<br />

19. Changing Horses<br />

bob dylan on <strong>U2</strong>/ van morrison on bob dylan/ <strong>U2</strong> on van morrison/ bob dylan on van morrison/ van morrison on <strong>U2</strong>/ bob dylan<br />

plays witn' van morrison & <strong>U2</strong>/ van morrison plays with bob dylan & <strong>U2</strong>/ dinner & drinks with bob dylan, van morrison, & <strong>U2</strong><br />

death in the family/ the clinton inauguration/ adam and tarry solicit a new singer/ everything don henley doesn't like/ bono and<br />

edge at the thalia theatre/ unbuttoning fascism's fly/ what the president said to the prime minister<br />

20. Approaching Naomi<br />

the darst dinner/ bono hosts the dating game/ love in the air/ the grammy awards/ two good reasons to resent eric clapton/ a<br />

quaker wedding<br />

22. Making Sausages<br />

songwriting by accident/ the movie critic/ one from column b/ a camera tour <strong>of</strong> adam's nakedness/ gavin's dirty duty/ the year <strong>of</strong><br />

the french<br />

23. In Cold Blood<br />

adam rallies the caravan/ a Serbian social studies lesson/ bono recites his latest poem/ the author's uncle has an audience with the<br />

blessed mother/ waiting for the end <strong>of</strong> the world<br />

24. Do Not Enter When Red Ligk Is Flashing<br />

25. Stay<br />

26. Macphisto<br />

a song for squidgy/ the salt in nero's supper/ a bag <strong>of</strong> money in the back <strong>of</strong> a taxicab/ adam experiences a mood swing/ the edge in<br />

his element<br />

watching bono write a song/ typical drummer's critique/ the big decision to go for an album/ flood's perspective/ bono the baby-<br />

sitter/ the great wanderer debate<br />

larry injects bull's blood/ eno proposes a library sytem/ fintan goes shopping for shoes/ songs are cobbled together/ bono paints<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (2 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

27. Business Week<br />

his face/ the zooropa tour begins/ hope for rich men to get into heaven<br />

the end <strong>of</strong> the record industry and other good news/ how <strong>U2</strong> ended up owning everything by being nice guys/ ossie kilkenny's<br />

virtual reality/ <strong>U2</strong>'s new deal/ mcguinness to prs: take your hand out <strong>of</strong> my pocket<br />

28. Dada's a Comfort<br />

the alertness <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> security/ neo-nazis stink up germany/ larry descends into underworld/ macphisto scares the bellboy/ a<br />

theology monograph from cyndi lauper<br />

29. Innocents Abroad<br />

30. Numb<br />

<strong>U2</strong> drives deep into germany/ the manager finds his manger/ fly the friendly skies/ larry brings down the berlin wall/ a video<br />

shoot is planned/ bono goes ton ton/ a guest editorial by johnny rotten<br />

the big video shoot/ whose foot is on edge's face/ more tall tales <strong>of</strong> the emerald isle/ post-chernobyl marriage shock/ hemingway's<br />

advice to rock stars/ a toast to reg, the star <strong>of</strong> the show<br />

31. The Olympic Stadium<br />

32. Jam<br />

deciphering the fuhrer's charisma/ calling down the ugly ghosts/ bono does the goose step/ the architecture <strong>of</strong> sociopathology/<br />

racing for the last plane home/ an ariel surprise party<br />

Italian gridlock/ pearl jam introduces stage-diving to verona/ the trouble with grunge/ news from the front/ a high-tech marriage<br />

proposal/ the wheel's still in spin<br />

33. The Masque <strong>of</strong> the Red MuuMuu<br />

34. Four Horsemen<br />

moonlight in verona/ planning the invasion <strong>of</strong> bosnia/ ping-pong with the supermodelsl an apostate is granted absolution/ pearl<br />

jam gets a sound check/ a dissertation on the value <strong>of</strong> men wearing dresses<br />

four ways <strong>of</strong> approaching the eternal city/ a surprise cameo by robert plant/ the cowboys <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> security/ a Vietnam flashback/<br />

naomi campbell vs. the kitchen staff/ a view from the roman balcony<br />

35. Words From the Front<br />

tension runs high over bono and bosnia/ paying <strong>of</strong>f the city inspectors/ why we weigh our tickets/ the pursuit <strong>of</strong> nancy wilson by<br />

concert security/ a dispatch arrives from the battle zone<br />

36. The Bosnia Broadcasts<br />

37. The Old Man<br />

38. Cork Popping<br />

39. Under My Skin<br />

<strong>U2</strong> establishes a satellite beachhead/ bill carter picks up some bullet holes/ an excruciating moment for larry mullen/ the english<br />

press eat <strong>U2</strong> for breakfast/ salman rushdie emerges from hiding<br />

bono's toughest critic/ his mother christened him paul, and paul he will remain/ when gavin almost got his ass kicked/ the myth <strong>of</strong><br />

the chess master deflated/ advice for the groom<br />

praise from some well-known presidents/ dodging the taoiseach/ Sebastian clayton's observations/ the last flight <strong>of</strong> the zoo plane/<br />

the man who could never go home/ edge on the value <strong>of</strong> heresy<br />

the walking tour enters its third day/ how edge lost the secret <strong>of</strong> the universe/ bono dubs a sinatra duet/ the old fool controversy/<br />

secondhand smokers/ a pub crawl with gavin/ michael jackson loses face<br />

40. Men <strong>of</strong> Wealth & Taste<br />

41. Dubliners<br />

the three levels <strong>of</strong> ligging/ salman rushdie, rock critic/ mick jagger sizes up the competition/ adam & naomi's public statement/<br />

bill carter learns to schmooze<br />

why joyce had to leave ireland to write ulysses/ the surrey with gavin friday on top/ <strong>U2</strong> turns into the virgin prunes/ wherefore<br />

wim wonders/ Sunday in the tent with bono<br />

42. Superstar Trailer Park<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (3 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

43. The Troubles<br />

44. Meltheads<br />

the mtv awards/ switching cerebral hemispheres/ a man in uniform/ "it looks like bono!"/ the pixies problem/ edge in love/ the<br />

many different ways to be a rock star<br />

scandal rocks the <strong>U2</strong> camp/ a trip to the gaultier show/ the gossip press/ "in the name <strong>of</strong> the father"/ catholics & protestants/<br />

proposed: Shakespeare was a lunatic/ falling into the television<br />

planning the triplecast/ alien ginsberg writes in the great book <strong>of</strong> Ireland/ the cyberpunk rules/ how far <strong>U2</strong> will go to get out <strong>of</strong><br />

rehearsing/ bono & gavin captured by british soldiers dressed as flowerpots<br />

45. Another Troy for Her to Burn<br />

46. Rancho Mirage<br />

47. Pressure Points<br />

the emperor's new clothes/ fachtna's version/ sex and politics/ sinead o'connor scares the studio crew/ <strong>U2</strong> as the justice league/ a<br />

moonlit journey over the halfpenny bridge<br />

sinatra sets some records/ bono's journey to the desert/ a swinging summit meeting/ a hasty retreat and relaxed reconciliation/<br />

mud in yer eye and scotch in yer crotch<br />

an understudy saves the big show/ an infestation <strong>of</strong> winged pests/ the sinking <strong>of</strong> the triplecast/ tiny tim as rorschach test/ larry's<br />

admonition against the aggrandizement <strong>of</strong> the lovey-dovey<br />

48. To Confer, Converse, and Otherwise Hobnob<br />

49. Skin Diving<br />

50. World AIDS Day<br />

51. Adam Agonistes<br />

52. Penny-Wise<br />

53. Tokyo Overload<br />

54. Judo<br />

55. Bono at Bottom<br />

56. Fin de Siecle<br />

57. Aftershocks<br />

macphisto's farewell address/ the veejay proposes date rape/ a frequent flyer causes panic in the aisles/ god blows on the<br />

soundman/ bono cuts <strong>of</strong>f michael Jackson's penis<br />

bono swipes a boat/ adam's hidden gifts/ a conga line forms at the gay bar/ a wager over underpants/ acquiring a postsexual<br />

perspective/ bono swipes a waitress/ bond! beach party<br />

flight <strong>of</strong> the zoo crew/ bono's soul leaves his body/ wine tasting in new Zealand/ the english-irish problem rears its head/ a<br />

meditation on rock stardom/ ascending mt. cavendish in a creaky gondola<br />

clayton at the crossroads/ a visit to the wonderbar/ bono does an art deal/ an aztec experience/ larry mullen: frugal or tightwad?/<br />

sunrise over one tree hill<br />

sore feelings above the pacific ocean/ tensions in the inner circle/ when adam and paul used to hunt as a pair/ this is not a band<br />

like most bands/ adam smith vs. the workers in the vineyard<br />

discovering japan/ kato's rebellion/ investigating the hostess trade/ larry encounters an ardent fan/ snake-handling is not an<br />

inherited skill/ sunrise like a nosebleed<br />

<strong>U2</strong> stops the traffic/ shootout in the noodle factory/ electric stained glass windows/ making the yakuza blink/ bono in the city <strong>of</strong><br />

the dead/ hal willner goes disco<br />

rejecting the brown rice position/ the future <strong>of</strong> the zoo tv network/ getting lost and missing sound check/ bono is left stripped and<br />

unconscious/ <strong>U2</strong> plays a stinker/ god isn't dead, nietzsche is<br />

the bomb japan scandal/ <strong>U2</strong>'s promoter banzais madonna's/ t-shirts save the day/ larry takes stock/ the 157th and final zoo tv<br />

concert/ the secret <strong>of</strong> the universe<br />

burning promises on the beach/ into the earthquake zone/ inducting bob marley/ the corrioles effect/ the charge <strong>of</strong> the cap/to/<br />

gang/ bono's promise to the young people<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (4 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

<strong>Index</strong><br />

58. The City That Doesn't Sleep<br />

59. Scoring<br />

the big bang <strong>of</strong> pop/ cutting <strong>of</strong>f the capol more news from Sarajevo/ irishmen in new york/ adam sets a few things straight/ what's<br />

the word?<br />

60. The Rest Is Easy<br />

time returns to its normal shape/ going to the world cup/ an outpouring <strong>of</strong> gaelic emotion and beer/ edge passes up a chance to<br />

meet the girl <strong>of</strong> his dreams/ Italian restaurants and Irish bars<br />

All God wants is a willing heart and for us to call out to Him<br />

<strong>U2</strong><br />

Author's Note<br />

The ideas, opinions, descriptions, and conclusions in this book are all mine. Although <strong>U2</strong> spent endless hours listening to my<br />

theories, answering my questions, and explaining their work and their workings, there are lots <strong>of</strong> things in here that some or all the<br />

members <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> will disagree with. That's okay. I'll stand behind it all. I am as pigheaded as any <strong>of</strong> them.<br />

Those aristocrats who fall on the floor writhing and swallowing their tongues when writers put rock & roll into the same boat as<br />

high art, poetry, philosophy, and other university subjects should get out now. You won't like it here. But if you want to<br />

understand <strong>U2</strong>, you have to understand how they draw from the highbrow stuff as well as the dumb things down in rock & roll's<br />

designated station.<br />

And it might save a fistfight or two if I spell this out: when I talk about <strong>U2</strong>'s relationship with Bill Clinton or Salman Rushdie or<br />

Wim Wenders or other cultural bigshots, it is not to suggest that <strong>U2</strong> influenced those people; it is to show how those people<br />

influenced <strong>U2</strong>.<br />

All right, that should shake <strong>of</strong>f the whiners. Let's go.<br />

I. BREZHNEV'S BED<br />

buzzing the reichstag/ bono faces eviction without his pants/ how <strong>U2</strong> got into this mess/ the hats vs. the haircuts/<br />

"one"/ channel surfing through the new world order<br />

bono wakes up in Brezhnev's bed. He can't remember where he is. When he opens his eyes the daylight shocks his dilated brain.<br />

He tries to organize his thoughts. He is in Brezhnev's bed, in East Berlin, in the communist diplomatic guest house rented to him<br />

for a good price because the communist diplomats have fled the country. In fact, the country has fled after them. He may have<br />

gone to bed in a Soviet satellite state, but he's waking in a reunited Germany. The Cold War is over! The Wall has fallen' It's safe<br />

for Bono to go back to sleep.<br />

He thought he heard somebody downstairs, but he must have been dreaming. He is here alone. Bono pulls himself upright, his<br />

latitude out <strong>of</strong> whack from last night's celebrating. <strong>U2</strong> arrived in Berlin yesterday, to seek inspiration and renewal at the<br />

celebration <strong>of</strong> the end <strong>of</strong> the world they grew up in. The Berlin Wall was raised as the four members <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> were being born.<br />

Seeing it come down shook their assumptions about the way things were and would always be. Bono told the Edge, Adam<br />

Clayton, and Larry Mullen that this was the great moment to leap into. Now was the time to go to Berlin and begin making music<br />

for the new world! They arrived on the last flight into East Germany before East Germany ceased to exist. They had the whole sky<br />

to themselves. The British pilot was so giddy with historical moment that he announced they would buzz Berlin, fly down the<br />

Strasse des Juni where the revelers were gathering, and swing over the broken wall on which the free people <strong>of</strong> eastern Europe<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (5 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

were dancing. "On your left you see the Brandenburg Gate," the pilot announced with pip-pip and tally-ho delight as he<br />

[2]<br />

swung his airship around. Why not? They were the only plane in the sky, the final flight to East Berlin before East Berlin was<br />

sucked into history.<br />

As soon as they got their feet on the ground, <strong>U2</strong> rushed to join the festivities. They leaped into the first parade they saw and<br />

waited for the contact high <strong>of</strong> liberation to intoxicate them. It was a long wait. These marchers were grim, dragging themselves<br />

along wearing dour faces and holding placards. Bono tried to muster some good Irish parading gusto, to no avail. He whispered to<br />

Adam, "These Germans really don't know how to party." Maybe, <strong>U2</strong> thought, we've misjudged the sentiment here. Maybe the<br />

proper reaction to the end <strong>of</strong> a half-century <strong>of</strong> oppression is not celebration for what is newly won but grief for all that can never<br />

be regained. <strong>U2</strong> looked at each other and looked at the bitter marchers and tried to fit in as they tramped along to the Wall. It was<br />

only when they got there and saw the joy everyone else was exhibiting compared with the morbidity <strong>of</strong> their company that <strong>U2</strong><br />

realized they were marching in an antiunification demonstration. They had hooked up with a phalanx <strong>of</strong> angry old communists,<br />

gathering one last time to show solidarity with the workers <strong>of</strong> the world and protest the fall <strong>of</strong> their Evil Empire.<br />

"Oh, this will make a great headline," Bono said. "<strong>U2</strong> arrives in<br />

west berlin TO PROTEST THE PULLING DOWN OF THE wall."<br />

In the West <strong>U2</strong> wandered familiar streets filled with people walking as if through their dreams. The citizens <strong>of</strong> the East—not just<br />

East Germany but the newly freed Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia— were still anxious, afraid that this was only a brief<br />

opening, a momentary aberration, and that if they did not find refuge quickly they would be dragged back when the communists<br />

regained their senses. For almost thirty years West Berlin had been held up to the East as a sort <strong>of</strong> capitalist Disneyland, shining<br />

with unattainable promise just over the barbed wire and gun towers. It was not just a symbol <strong>of</strong> freedom, it was the closest thing<br />

the oppressed peoples had to Oz. Their belief in its magic was not stifled by their own leaders warning them to pay no attention to<br />

that world behind the iron curtain. But in the year since people from the East began moving West, first as a trickle through<br />

Hungary and Czechoslovakia and then in a flood right through the falling Wall, the free people <strong>of</strong> West Germany have become a<br />

little less tickled with the family reunion. As Easterners looked to share in the prosperity <strong>of</strong> the west, the Westerners began to fear<br />

being saddled with<br />

[3]<br />

the poverty <strong>of</strong> the East. Great to see you, Cousin, seems to be the prevailing sentiment. When are you leaving?<br />

Now that <strong>U2</strong> could walk back and forth from the East to the West, they realized that the sense <strong>of</strong> West Berlin as illuminated was<br />

not an illusion. The lights were literally brighter. The streetlamps <strong>of</strong> the East were dull, dirty yellow. The streetlights <strong>of</strong> the West<br />

were golden and white, and <strong>of</strong> higher wattage. The West had better generators. Bono was especially struck by the glow <strong>of</strong><br />

ultraviolet lights in the windows <strong>of</strong> Eastern buildings so crowded together that little sunlight got through. Bono had associated the<br />

purple glow <strong>of</strong> UV lighting with nightclubs and raves, but to the East Germans it represented an attempt to grow flowers in the<br />

shadows.<br />

<strong>By</strong> the sides <strong>of</strong> the streets in the West were the abandoned, burned-out carcasses <strong>of</strong> Trabants, the comically cheap automobiles<br />

manufactured in East Germany. Refugees had driven the Trabants as far as they'd go, and then left them where they died to<br />

continue their migrations on foot. Big trucks full <strong>of</strong> East German currency were rolling up to West Berlin banks to exchange<br />

bales <strong>of</strong> useless money for deutsche marks to pay the soldiers <strong>of</strong> the disintegrating communist army. The spirit <strong>of</strong> Berlin felt<br />

less rapturous, more mundane, than <strong>U2</strong> had thought it would. They passed the one subway terminal where heavily patrolled<br />

trains had been allowed to move from East to West, and where East Germans trying to sneak aboard had been killed. They took<br />

note <strong>of</strong> its name: Zoo Station.<br />

At 7 in the morning exhaustion dropped on their history-happy heads and <strong>U2</strong> were led to the accommodations Dennis Sheehan,<br />

their road manager, had arranged. For Bono it was this private house where Soviet <strong>of</strong>ficials had lodged, and the special comfort<br />

<strong>of</strong> Brezhnev's bed.<br />

So this morning Bono, full <strong>of</strong> emotion and alcohol, should be sleeping like Lenin but something has awakened him. He crawls<br />

out <strong>of</strong> bed hoping for a glass <strong>of</strong> water and, in his hungover state, wanders down into the basement. While standing there, naked<br />

from the waist down, dressed only in a dirty T-shirt, he thinks he hears low voices and the rattling <strong>of</strong> doorknobs. Someone is<br />

trying to get into the house. He creeps up the stairs and sees that the intruders are inside already! Bono is suddenly aware, like<br />

Adam in the Garden, that he has no pants on and his cock is hanging out. As the intruders enter the hallway where Bono is<br />

crouching he tries to cover his nuts with one hand while with the<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (6 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

[4]<br />

other waving and in his hoarse voice declaring, "This is my house! You do not belong here!"<br />

Bono is unprepared for the response he gets from the ringleader, an elderly German man, who shouts back, "This is not your<br />

house! This is my house! You get out!" Bono, bent over with his balls in his hand, surveys the gang <strong>of</strong> home invaders, a middleaged<br />

to elderly family <strong>of</strong> six filing in cautiously behind the firm father, who seems prepared to jump on Bono and wrestle him to<br />

the floor. Bono is disoriented. He feels like a kid caught trespassing by his elders, not a wealthy international figure whose<br />

accommodations have been intruded upon. "This is my house!" the old man repeats. And as Bono stumbles to try to find his<br />

German and sort our the confusion, it becomes apparent that the old walrus is not misdirected. This is their house. They were<br />

visiting the western side <strong>of</strong> town in 1961 when the Wall went up. Now they arc home, and they want their house back.<br />

And so it comes to pass that Bono and the rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> end up checking into a particularly ugly East Berlin hotel (no rooms in the<br />

West!) while bellhops disconnect the KGB security cameras and unscrew the bedposts to check for Stasi bugs. There are<br />

prostitutes in the lobby trying to organize some currency exchanges. Bono knows well the unspoken meaning <strong>of</strong> the doleful looks<br />

he gets from Adam, Edge, and Larry. He's been getting them since they started their schoolboy band fourteen years ago. The looks<br />

say, "Another <strong>of</strong> your great ideas, Bono, another inspiration."<br />

It is the autumn <strong>of</strong> 1990 and <strong>U2</strong> has spent the year out <strong>of</strong> the public eye. Playing an emotional concert at home in Dublin on the<br />

last night <strong>of</strong> the 1980s, Bono told the audience, "We won't see you for a while, we have to go away and dream it all up again." It<br />

was widely speculated in the press that this meant <strong>U2</strong> was breaking up. In fact it just meant that the band knew that the musical<br />

line they had been following had run out <strong>of</strong> track. On tour in Australia in the autumn <strong>of</strong> '89 Larry had told Bono that if this is what<br />

it meant for <strong>U2</strong> to be superstars, he didn't like it. They were turning into the world's most expensive jukebox. They became so<br />

bored playing <strong>U2</strong>'s greatest hits that one night they went out and played the whole set backward—and it didn't seem to make any<br />

difference.<br />

It sure didn't help that the critics had turned against <strong>U2</strong> with neck-snapping speed. Their album <strong>U2</strong> Rattle and Hum—conceived as<br />

a throw-<br />

[5]<br />

away, bargain-priced grab bag <strong>of</strong> live tracks and rootsy originals to accompany their live concert film—had been savaged in the<br />

press as a pretentious attempt to place <strong>U2</strong> in the company <strong>of</strong> Bob Dylan, the Beatles, Â. Â. King, Billie Holiday, Jimi Hendrix,<br />

John Coltrane, and all the other musical seraphim the album celebrated. <strong>U2</strong> claimed the record was meant to show that even<br />

they, the biggest band in the world, were still fans. That explanation struck critics as conceited too. <strong>U2</strong> walked into the sucker<br />

punch with their chins stuck out and their hands in their pants. On an album dizzy with roots references, hero worship, and<br />

collaborations with rock legends, Bono was thoughtless enough to sing, "I don't believe in the sixties, in the golden age <strong>of</strong> pop/<br />

You glorify the past when the future dries up."<br />

<strong>U2</strong> jokes circulated in the music industry. "How many members <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> does it take to change a lightbulb?" "Just one: Bono holds<br />

the lightbulb and the world revolves around him."<br />

What stung more than the misunderstanding <strong>of</strong> their musical intentions was that so much <strong>of</strong> the criticism was personal. Since they<br />

began, <strong>U2</strong> had sung about what was in their hearts and on their minds. In their music and in their public pronouncements, as in<br />

their personal lives, they were quick to share what they had just heard, just read, just figured out. They were by nature truth-tellers,<br />

and Bono was by nature a big mouth. The great thing about such openness was that fans who paid close attention to <strong>U2</strong> really did<br />

know them, had a genuine connection to them. But in the last couple <strong>of</strong> years that was less than comforting, as it also meant that<br />

those who ridiculed the band were not just mocking the music, they were mocking the four people.<br />

The more sensitive <strong>U2</strong> became about being misunderstood, the more they tried to control how they presented themselves. I<br />

suggested to the Edge that maybe the band brought some <strong>of</strong> the accusations <strong>of</strong> self-seriousness on their own heads by maintaining<br />

such rigid control <strong>of</strong> their image. The film Rattle and Hum had been tightly supervised by <strong>U2</strong>, so if they came <strong>of</strong>f as humorless<br />

and self-important, it was considered not the fault <strong>of</strong> the director, but <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong>. In the same way, they were very selective about who<br />

got to interview them, and almost all the photos <strong>of</strong> the band available to the press were Anton Corbijn's moody, <strong>U2</strong>-controlled<br />

shots <strong>of</strong> stoic men standing stone-faced in deserts or snow.<br />

I'm all for propaganda!" Edge grinned. "It is a fine line and you're going to get it wrong sometimes. I think we're aware that<br />

maybe that is<br />

[6]<br />

part <strong>of</strong> why we ended up being the caricature. A little bit. Rattle and Hum, the movie, was an example <strong>of</strong> that. We were<br />

criticized by some people for not revealing more. We actually made quite a conscious decision not to reveal more, because we<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (7 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

[7]<br />

didn't feel comfortable with it. It is a balance, because you have to give up so much more when you reveal all. It's like you no<br />

longer have a private life. But at the same time, if you don't reveal all, people don't really get the full picture. So it's a<br />

compromise. With Rattle and. Hum we just didn't want to reveal ourselves. My attitude was, 'What? Do you think we're crazy?<br />

Cameras in the dressing room? What do you think we are—stupid!'<br />

"I love what we do, because we control it. Because we've set it up where we're comfortable with it. That's why we could do it.<br />

<strong>If</strong> it was done in a way where our private lives were an open book, I don't think I could be in the band. I didn't get into the band<br />

to become a celebrity. I got into the band because I wanted to play music and write songs and tour and do all that stuff. Some<br />

people might object to that but I say, 'Well, fuck you!' " He laughed. "It's my life and this is the way it works for me."<br />

Lately Bono likes to quote Oscar Wilde: "Man is least himself when he talks in his own person; give him a mask and he will<br />

tell you the truth." One <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong>'s assignments in Germany is to figure out if it's possible, ten years into their public lives, to<br />

construct masks that will allow them to say exactly what they are thinking in their songs while providing some sort <strong>of</strong><br />

protection for their personal lives. They have realized, with the forehead-slapping regret <strong>of</strong> late bloomers, that the Rolling<br />

Stones, Bob Dylan, and Led Zeppelin figured all this stuff out before they got famous; by adopting public personas they could<br />

establish some space between their on-duty and <strong>of</strong>f-duty lives. <strong>U2</strong> spent their first ten years keeping nothing for themselves.<br />

They won't screw that up again.<br />

The band assembles at the Hansa recording studio not far from the Berlin Wall. The place was once a Nazi ballroom. In the<br />

mid-seventies it was the site <strong>of</strong> some groundbreaking work by David Bowie, who in collaboration with producer Brian Eno<br />

made a trilogy <strong>of</strong> albums. Low, Heroes, and Lodger, that stretched the conventions <strong>of</strong> rock & roll into the corners <strong>of</strong> European<br />

experimental music. <strong>U2</strong> heard about the glory <strong>of</strong> those days when Eno was co-producing the <strong>U2</strong> albums The Unforgettable<br />

Fire and The Joshua Tree. On Heroes, Bowie found a grand metaphor in<br />

Berlin's division. Bono cooked up the notion that by coming to Hansa now, <strong>U2</strong> could tap into the spirit <strong>of</strong> reunification. It was a<br />

nice idea, but if ideas like that worked, English pr<strong>of</strong>essors would be successful writers. Instead <strong>U2</strong> discovers when they get into<br />

Hansa that the studio has deteriorated since Eno and Bowie left there twelve years before. There is constant talk <strong>of</strong> the area being<br />

condemned and the building knocked down, so no one has kept Hansa humming. The two producers, Dan Lanois and Flood, will<br />

have to import their own recording equipment.<br />

But that's not the big problem. The big problem is that the four members <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> cannot agree on the value <strong>of</strong> the new material that<br />

Bono and Edge play for Larry and Adam, or on the sense <strong>of</strong> the new direction in which Bono and Edge want to steer the band.<br />

Edge has been swimming in experimental music, noise rock, electronics, and alternative guitar sounds. He comes in lecturing his<br />

bandmates about Insekt, Nitzer Ebb, Nine Inch Nails, KMFDM, and Front 242—stuff that sounds like walkie-talkies in washing<br />

machines.<br />

Larry, the no-nonsense drummer, says he doesn't know any <strong>of</strong> those people. Well, Edge asks, what have you been listening to?<br />

Led Zeppelin, says Larry. Jimi Hendrix. Trying to figure out how other bands in <strong>U2</strong>'s position did it and catching up on music he<br />

ignored during the postpunk era when <strong>U2</strong> grew up.<br />

Bono tries siding with Edge, talking about getting out <strong>of</strong> the seventies, raving about how the rappers have used high tech to make<br />

a core connection back to their souls, and saying that <strong>U2</strong> should check out dance rhythms as the Manchester bands Stone Roses<br />

and Happy Mondays do. That is too much for Adam, who spends more time in clubs and discos than the other three combined<br />

and who thinks Bono trying to be hip just shows how out <strong>of</strong> it he really is. Manchester is over. Adam's attitude is as it has always<br />

been: can we cut the bullshit and get to the music? But this time there doesn't seem to be any music to get to. This time it seems<br />

less like a band than a debating society.<br />

A division is quickly established between the Hats, Edge and Bono, and the Haircuts, Larry and Adam. Lanois, who became<br />

almost a fifth number <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> on Unforgettable Fire and Joshua Tree, is clearly leaning toward the Haircut position, which only<br />

makes Bono and Edge more defensive. Lanois's attitude is: You can only be what you are and we know what <strong>U2</strong> is. Why try to<br />

pretend to be something else?<br />

[8]<br />

It has never been this hard for <strong>U2</strong> before. The band members begin to consider that they really have reached the end <strong>of</strong> the line<br />

together, that Rattle and Hum was the start <strong>of</strong> a downhill slide they'd be best <strong>of</strong>f halting before it goes any further. They have<br />

some demos they cut at a small Dublin studio in the late summer, but Larry and Adam don't think those songs are particularly<br />

good. Their attitude is: We tried our best to make something out <strong>of</strong> these in Dublin, now we've tried in Berlin; let's admit it's<br />

not happening. Bono keeps trying to make something out <strong>of</strong> a track called "Who's Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses" that the<br />

others would as soon toss in the toilet. They have the outlines for songs called "Acrobat," "Real Thing," "Love Is Blindness"<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (8 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

[9]<br />

and "Tryin' to Throw Your Arms Around the World." Bono and Edge won't give up on one chorus—"It's alright, it's alright, it's<br />

alright/She moves in mysterious ways," even though Edge keeps changing all the music around it to try to find something<br />

worth making a song from.<br />

Bono's attitude is that he and Edge may not have come back to the band as sharp as they should have, "but we are both a lot<br />

sharper than Larry and Adam!" Bono's wide-eyed raps about junk culture and disposable music are met with disinterest from<br />

Adam and impatience from Larry, who finally says, "What the fuck ãàå you talking about?" Larry says there's a simple<br />

problem here: "You haven't written any songs' Where are the songs?"<br />

That really goes up Bono's ass sideways. When Bono and Edge started abandoning the <strong>U2</strong> tradition <strong>of</strong> all four <strong>of</strong> them writing<br />

together and brought in songs on their own, Larry was the first one to bitch that he and Adam weren't getting enough input,<br />

were being forced into a predetermined structure. But now that Bono's laying the burden on the four <strong>of</strong> them again, Larry<br />

wants the songs written for him. There's a fight brewing.<br />

Bono and Larry represent the two poles <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong>—Bono is the most open to new ideas, fads, impulses, innovation, and<br />

rationalization. Larry is the most conservative, steady, and grounded. When one <strong>of</strong> Bono's ideas leaves the realm <strong>of</strong> reality, it is<br />

Larry who calls time-out. In the past they both appreciated that balance, and everyone could laugh about their contrary traits.<br />

Now, though, it feels different. It feels less like two sides <strong>of</strong> one coin than two entirely separate currencies.<br />

Larry accuses Bono <strong>of</strong> not knowing who he is, which Bono throws back at him, saying Larry always knows who Larry is<br />

because Larry<br />

Clever changes. "You haven't changed your haircut in ten years!" Bono says, "Yes, I sometimes fail, but at least I'm willing to<br />

experiment." Bono accuses Larry <strong>of</strong> not knowing how to improvise.<br />

(Much later, Bono says, "I'm actually in awe <strong>of</strong> Larry for knowing exactly who he is. I don't know if I'm this or that or what.<br />

But why can't I be all <strong>of</strong> them?" Another time he says, "<strong>If</strong> I knew who I was I wouldn't be an artist, I wouldn't be in a band, I<br />

wouldn't be here screaming for a living.")<br />

Adam's attitude is that he and Larry aren't the ones who didn't do their homework. The rhythm section put in their time on the<br />

Dublin demos. Then Bono and Edge were supposed to go <strong>of</strong>f and write melodies, words, guitar hooks, and fill in any missing<br />

sections in the compositions. Adam thinks Bono's rhetoric is partly a disguise for his not having taken care <strong>of</strong> the<br />

fundamentals. "I'd really love to make a rhythmic record," Adam says. "I'm a bass player! Why wouldn't I? I don't know much<br />

about industrial music, but as long as there's a song I'll be rhythmic, and if you want to change the sounds to be industrial, fine.<br />

There's a point in the process where Larry and I have done everything we can do and we leave it to Bono and Edge to finish the<br />

songs. But those things we did in Dublin haven't really advanced."<br />

That's not how Bono sees it. He broods that by bringing up references to dance culture—not just to current trends but even to<br />

the Rolling Stones' "Miss You" and "Emotional Rescue"—he is putting the Creative obligation back on the rhythm section.<br />

"Adam knows," Bono says, "that I'm putting the weight back on him."<br />

Bono says that on this album he wants to explore the subject <strong>of</strong> sex and fidelity. "Rhythm is the sex <strong>of</strong> music," he says. "<strong>If</strong> <strong>U2</strong><br />

is to explore erotic themes, we have to have sexuality in the music as well as the words. The flat rhythms <strong>of</strong> white rock & roll<br />

have had their day. Rhythm is now part <strong>of</strong> the language." At the tensest moments Bono even asks Edge if he thinks Adam is<br />

deliberately dragging his ass on the bass parts in order to sabotage this new musical direction.<br />

In the middle <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> Bono's criticisms one especially touchy afternoon Adam takes <strong>of</strong>f his bass, holds it out to Bono, and says,<br />

"You tell me what to play and I'll play it. You want to play it yourself? Go ahead."<br />

Thus the Hansa sessions crawl along, with Berlin getting darker and colder. Everyone's freezing all the time and it seems to<br />

never stop<br />

[10]<br />

raining. They eat most nights in a gray, oppressive gruel hall. With nothing else to do short <strong>of</strong> disbanding, <strong>U2</strong> keep plodding<br />

along, trying to figure out a way to take their music into the nineties and feeling like they're getting nowhere. Edge is getting<br />

frustrated with Lanois, who he thinks just doesn't get it. Larry defends Lanois.<br />

Edge comes in one afternoon and there's Lanois in the studio, playing guitar and singing, desperately trying to make a new<br />

song called "Down All the Days" sound like the old Joshua Tree <strong>U2</strong>. "He's really panicking," Edge says. "I had no idea<br />

Danny was so confused by what we were doing."<br />

Edge starts thinking that maybe the rumors that <strong>U2</strong> was going to disband after the New Year's show were prophetic. "Maybe<br />

this is what we should do," he admits. "Maybe we should break up and see what happens."<br />

It seems like every time <strong>U2</strong> starts to get going musically something goes wrong, someone makes a mistake. When that<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (9 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

happens Bono—not known for keeping his feelings to himself—howls his frustration. This really gets on his partners'<br />

nerves. Finally they get together and impose a band ruling: the hyped-up Bono is permanently forbidden to drink c<strong>of</strong>fee.<br />

<strong>U2</strong> needs some objective ears. Brian Eno, producer with Lanois <strong>of</strong> their two best albums and the historic Mensa <strong>of</strong> Hansa, is<br />

drafted to come in for a few days and listen to what they've done. It turns out to be a great relief. Eno—thin, pale, and ascetic<br />

—has the patience <strong>of</strong> a university pr<strong>of</strong>essor taking over a class <strong>of</strong> unruly freshmen. He is able to mediate between Edge's<br />

ambitions and his old partner Lanois's resistance. He goes to the board and shows how, by adding oddball vocal effects and<br />

a few jarring sounds, it's possible to bring some <strong>of</strong> the more conventional material <strong>U2</strong> has been fiddling with into fresh sonic<br />

territory. Eno assures the frustrated band that they're doing better than they think, and that Edge's desire to get into new<br />

acoustic areas is not incompatible with Danny and Larry's desire to hold on to solid song structures.<br />

"Eno is the person both Bono and Edge really connect with," Adam says. "Intellectually they can bounce ideas <strong>of</strong>f him. Eno isn't<br />

loyal to any philosophy for very long. It's no problem for Eno to say, 'Okay, if that's the type <strong>of</strong> thing you want to do, here's how<br />

we do it.' Where Danny has been saying, 'Okay, that's what you want to do, but I'm this kind <strong>of</strong><br />

[11]<br />

record producer and you're that kind <strong>of</strong> band, so let's make what you're trying to do happen through what you've always done<br />

before.' So Eno's important. What Eno won't do is take responsibility. He won't let you <strong>of</strong>f the hook. And that's fine."<br />

Eno's input gives <strong>U2</strong> encouragement to keep working, but it does not settle their stomachs. One night they are struggling with a<br />

track called "Ultra Violet" and it's going nowhere. Edge figures the song needs another section and goes to the piano in the big<br />

room to come up with a middle eight. After playing for a while he has two possible parts and isn't sure which one would be<br />

better for the song. He comes back into the control booth, picks up an acoustic guitar, and plays both <strong>of</strong> them for Lanois and<br />

Bono to see which they prefer. They say that those both sound pretty good—what would it be like if you put them together?<br />

Edge goes back out into the studio and starts playing the two sections together, one into the other. Larry and Adam fall in<br />

behind him on the drums and bass. Bono feels the muse knocking on his head as surely as in one <strong>of</strong> those old Elvis movies<br />

where the king jumps up in the middle <strong>of</strong> a clambake and starts rocking. Bono goes out to the microphone and begins<br />

improvising words and a melody: "We're one, but we're not the same—we get to carry each other, carry each other."<br />

<strong>U2</strong> plays the new song for about ten minutes. "Is it getting better," Bono sings, "or do you feel the same? Is it any easier on you<br />

now that you've got someone to blame?" Edge feels that it's suddenly all jelling— the band is clicking and all four <strong>of</strong> them<br />

know. They come into the booth and listen to a playback with a relief close to joy. <strong>By</strong> the next morning they have recorded<br />

"One," as strong a song as <strong>U2</strong> has ever written. It came to them all together and it came easily, as a gift.<br />

"Phew," Edge jokes, "the ro<strong>of</strong> for the house in the west <strong>of</strong> Ireland is looking good! I'll be able to change the car this year after<br />

all!"<br />

There's still an enormous amount <strong>of</strong> work to do, but at least <strong>U2</strong> knows they can still bring good music out <strong>of</strong> each other. "I<br />

suppose in the back <strong>of</strong> your mind everyone thinks that maybe one day we're going to write together and we just won't have<br />

anything to say," Edge explains. "Literally, there will be nothing more to add. You all hope that everyone knows when that time<br />

has come and you don't go on and do some completely awful album that everyone recognizes to be a disaster."<br />

He thinks "One" represents the turning point away from that ugly proposition. <strong>U2</strong> agrees they should get out <strong>of</strong> Berlin and pick<br />

up this<br />

[12]<br />

thread again at home, in Dublin. They decide they will move out <strong>of</strong> Germany in January <strong>of</strong> '91. Larry feels, though, that there's an<br />

issue even bigger than the music to resolve before <strong>U2</strong> goes forward. The band grew out <strong>of</strong> friendship between the four <strong>of</strong> them, he<br />

says, and if it's a choice between continuing the friendships or continuing the band, <strong>U2</strong> has to go.<br />

So during a Christmas break in Dublin the four members <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> engage in heart-to-heart talks about what they expect from each<br />

other, as partners and as friends. Listening to the Hansa tapes again after a break, they sound a lot better than they did in Germany.<br />

There's plenty <strong>of</strong> good material there to work with and they decide that they can again trust each other enough to go through it<br />

together.<br />

"There is a love between the members <strong>of</strong> this band that is deeper than whatever comes between us," Larry says after the armistice.<br />

"After almost fifteen years, which would be time for a divorce in almost any relationship, we looked at each other and said, 'Lay<br />

down your arms.' "<br />

They have to go back to Berlin in January to finish some bits before setting up in Dublin. While they are packing up, war breaks<br />

out in the Middle East. It's been building up the whole time <strong>U2</strong> has been recording—Iraq invaded Kuwait last summer and the<br />

United States began assembling an alliance to threaten them into withdrawal. It was the first test <strong>of</strong> President George Bush's New<br />

World Order, an international scheme in which the East-West, communist-capitalist schism was to be replaced by a pyramid <strong>of</strong><br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (10 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

interconnected nations (with, needless to say, America on top). A current bestseller refers to this moment, the proposed dawning<br />

<strong>of</strong> a post—bipolar world, as "The End <strong>of</strong> History." The British techno-pop band Jesus Jones even has a big hit this week called<br />

"Right Here, Right Now," about the same subject: "Right here, right now—watching the world wake up from history."<br />

Right here, right now, it's looking like the end <strong>of</strong> Saddam Hussein's history anyhow. Bush got the Europeans to agree to impose a<br />

deadline on Iraq, after which if they didn't pull out <strong>of</strong> Kuwait they'd be attacked. Then he convinced the Soviets to come in, the<br />

Japanese, most <strong>of</strong> the other Arab states, and even China. While waiting for Saddam to back down, the rest <strong>of</strong> the world slapped<br />

Iraq with an embargo and diplomatic sanctions.<br />

That Saddam, Iraq's dictator, is an obvious nut with eyes on grabbing other oil-producing neighbors was a big incentive to the<br />

Middle<br />

[13]<br />

Eastern states to join with the U.S. (and Israel!) in this crusade. Iraq had previously invaded Iran, so there was no hope <strong>of</strong> help<br />

coming for Saddam from the Islamic fundamentalists. Feeling a bit overextended, the Iraqi ruler even tried lobbing a few<br />

missiles at Tel Aviv, hoping to unite the Arabs in a holy war against the Jews. The Arabs didn't bite.<br />

The countdown to the U.N. deadline has been dominating the news for a couple <strong>of</strong> weeks, but still, it's a shock to hear that the<br />

war has begun and U.S. missiles are blowing up downtown Baghdad. Bono sits at the TV transfixed, amazed that CNN is<br />

broadcasting the war live twenty-four hours a day, and that he—like millions <strong>of</strong> TV viewers— finds himself watching war as if<br />

it were a football match. He turns on a movie, switches to the war for a while, over to MTV, back to the war:<br />

Whoa, look at those missiles! That was a big one!<br />

Edge is struck by the fact that the young pilots returning from bombing raids and the soldiers directing the missiles from<br />

launchpads far from Baghdad <strong>of</strong>ten compare what they're doing to playing video games at home. It is all computer controlled,<br />

they never see any blood or destruction—children who grew up using toys to pretend they were at war end up at war<br />

pretending they're using toys. They fly <strong>of</strong>f on missions with the Clash's "Rock the Casbah" blaring. Edge and Bono are<br />

watching TV together when a young American pilot is interviewed on CNN. When asked what the bombing looks like from<br />

the plane, he says, "It's so realistic." Bono and Edge look at each other, amazed.<br />

Bono thinks that something fundamental has changed, not just in the world's political structure, but in the way media has<br />

permeated the public consciousness. In the last decade cable TV has spread through what used to be called the free world.<br />

There is no more line between news, entertainment, and home shopping. Bono says that when <strong>U2</strong> tour behind this album,<br />

they have to figure out a way to represent this new reality.<br />

2. Dogtown<br />

the toughest guy in the band/ why rich people have no friends/ the wives will kill us/ <strong>U2</strong> in nighttown/ adam exposes<br />

himself/ springtime for bono<br />

everything is easier in Dublin in the spring <strong>of</strong> '91. Everything musical anyway. One <strong>of</strong> the side effects <strong>of</strong> starting up the <strong>U2</strong><br />

machine again is the havoc it causes in the home lives <strong>of</strong> the members. Adam, a swinging bachelor, has nothing to keep him from<br />

commiting to a long stretch on the road. Larry has a longtime girlfriend named Ann Acheson, but they have no children and she<br />

has her own life and work.<br />

It's different for Bono and Edge, who have both been married for years and have young children. Edge has three daughters. Bono<br />

has a two-year-old girl and a second on the way. Their wives have the right to say that after putting their marriages aside for<br />

months or even years at a time in order for <strong>U2</strong> to conquer the world, they might have expected, now that all the band's goals had<br />

been reached, to settle into a more normal family life. Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and Bob Dylan all quit touring after hitting the<br />

top and devoted themselves to making records and living with their wives and children. <strong>U2</strong> is now talking about releasing the new<br />

album in the autumn <strong>of</strong> '91, touring America and Europe in the spring <strong>of</strong> '92, going back to America in the summer and fall <strong>of</strong> '92<br />

if the demand is there, and then, if things go really well, touring Europe again in '93. As the band returns to Dublin with their<br />

unfinished album, they are looking at a work schedule that will cause them to put their domestic lives on hold for the next three<br />

years.<br />

There are boxes within boxes in the <strong>U2</strong> organization, and what goes on between the band members and their families is in the<br />

smallest box <strong>of</strong> all. I don't know what finally sets it <strong>of</strong>f and it's surely nobody's<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (11 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

[15]<br />

business, but around Easter Edge moves out <strong>of</strong> his home and away from his wife, Aislinn. He settles into Adam's guest house<br />

and work on the album continues.<br />

"I could tell stories <strong>of</strong> times each <strong>of</strong> the others has been there for me," Edge says at dinner one night. "I mean, there have been<br />

periods when Adam and I didn't particularly get along, over the years. Yet when I left Aislinn I moved into Adam's." Edge, who<br />

is rarely inarticulate or sentimental, has a little trouble getting the next words out: "I suppose that the other three are the closest<br />

friends I have."<br />

That friendship can be tough for any outsider to penetrate. And no one's tougher to tie down about it than the hardheaded Larry<br />

Mullen.<br />

"People say, 'Why don't you do interviews? What do you think about this? What do you think about that?'" Larry sighs. "My<br />

job in the band is to play drums, to get up on stage and hold the band together. That's what I do. At the end <strong>of</strong> the day that's all<br />

that's important. Everything else is irrelevant."<br />

Many people on this planet say they hate horseshit, but no one hates horseshit as much as Larry Mullen, Jr., does. The<br />

possibility that he might somehow add to the rising stew <strong>of</strong> crap that threatens to submerge our civilization in hype and<br />

nonsense appalls him so much that he slaps on a scowl and shuts his mouth at the first inkling <strong>of</strong> glad-handing, backslapping,<br />

false sincerity, sucking up, ass-kissing, air-kissing, overpraise, fair-weather friendship, freeloading, hyperbole, ligging,<br />

flattery, posturing, complement chewing, ego-stroking, bootlicking, cheek-smooching, groveling, pratspeak, toadying, leglifting,<br />

fame-grubbing, schnoring, idol worship, starfucking, or brown-nosing. Boy, did he pick the wrong business!<br />

Bono says that with Larry everyone is presumed guilty until proven innocent—but if he makes up his mind that you're okay<br />

he'll not only let you into his house, he'll let you sleep in his bed.<br />

Larry's always been tough. He can laugh heartily telling the story <strong>of</strong> how as little kids on Christmas Eve he and his sister kept<br />

pestering their father, saying, "I think I hear Santa, Dad! I think I hear Santa!" Until their annoyed old man said, "There is no<br />

Santa Claus! Now go to sleep!" When his mother told him he could not go <strong>of</strong>f, underage and illegal, to play in bars with <strong>U2</strong>, he<br />

told her flat out that he had to do it, there was nothing to argue about. And <strong>of</strong>f he went.<br />

Larry effectively founded <strong>U2</strong> at Mount Temple, their Dublin high<br />

[16]<br />

school when he approached Dave Evans (Edge) about starting a band. Word got out and Paul Hewson (Bono), Adam, and a few<br />

other kids came by Larry's family's kitchen to bang on guitars and sing cover tunes. Before long membership was knocked down<br />

to the four characters who remain <strong>U2</strong> today. Edge was a couple <strong>of</strong> months older than Larry. Adam and Bono both had more than a<br />

year on him. With his blond hair and pretty features, Larry looked younger than the others. He looked like a little kid. But Larry<br />

was always as bullheaded as a minotaur. He has joked that he gave up on being leader <strong>of</strong> the group as soon as he met Bono, but in<br />

some indefinable way he has remained the center <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> from high school to here. It's not even that he's the band's conscience;<br />

it's more that he's the one who knows what each <strong>of</strong> them is and what each <strong>of</strong> them might or can never become, and he will never<br />

hesitate to say so to any <strong>of</strong> their faces. Somehow, by defining that, Larry defines what <strong>U2</strong> ends up being.<br />

"What's made <strong>U2</strong> has always been the relationship," he says. "The relationship has not only been a personal one, it's also been a<br />

musical one. It's been an understanding. It's a cliche, but <strong>U2</strong>'s biggest influences have always been each other. We've always<br />

played with each other. We've always played against each other musically. When we came to Berlin we were suddenly,<br />

musically, on different levels and that affected everything. The musical differences affected the personal differences.<br />

"It's a very, very strange world that we live in. I was very young when the band started. I ended up doing it because <strong>of</strong> tragedy, in<br />

some ways. My mother died and I went straight into the band, that was the kick. On the road I was surrounded by people who<br />

were older than me and more experienced than I was. I was seventeen. I was a virgin. I had difficulty as any normal teenager<br />

would.<br />

"When you're a kid and you're thrown into this, it's very hard. Some people cope with it better than others. I feel that I'm less<br />

affected now than maybe some <strong>of</strong> the other guys are because I have fallen in love with this. I loved it when I was a kid, then<br />

when I went on the road it was so difficult I just didn't know what was going on, it was very hard. Then, after a whole lot <strong>of</strong><br />

different things happening with the band being successful, I made a very clear decision in my own mind that this is really what I<br />

want to do and I want to make a serious go <strong>of</strong> it. I don't just want to be the drummer in <strong>U2</strong> anymore. I want to actually contribute<br />

on a different basis and do more."<br />

[17]<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (12 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

When Larry says he was kicked into <strong>U2</strong> because his mother died (she was killed in a traffic accident around his seventeenth<br />

birthday), he is tapping into a secret history <strong>of</strong> rock & roll. Losing his mother as a kid is a tragedy Larry shares with John<br />

Lennon, Paul McCartney, Jimi Hendrix, Madonna, Sinead O'Connor, and Bono. Throw in Elvis Pres-ley and Johnny Rotten,<br />

two singers very close to mothers who died just after they got famous, and you have a pretty good representation <strong>of</strong> the biggest<br />

blips on rock & roll's forty-year seismograph. Bono lost his mother in 1974, when he was fourteen. She collapsed from a stroke<br />

at her own father's funeral and died immediately thereafter.<br />

Larry says having that loss in common brought Bono and him together. "There was a connection there," he explains. "He<br />

understood a little <strong>of</strong> what I felt. I was younger than him. I didn't have any brothers. My father was out <strong>of</strong> whack anyway, so<br />

Bono was the link. He said, 'Look, I understand a bit what you're going through. Maybe I can help you.' And he did. Through<br />

thick and thin he's always been there for me. Always.<br />

"People think the band is this unit that's always together. We fight and argue all the time! But I have to say that through it all<br />

Bono has always been there. And that was where it started, that was the original connection. When I was in deep shit, he made<br />

himself available for me, he was around. Even on the road when I was going through a rough time I used to share a room with<br />

him. He just used to make sure I was okay." Suddenly Larry smiles and says, "It was a bit like baby-sitting, y'know what I<br />

mean?"<br />

I ask Larry how his life was affected by becoming wealthy.<br />

"It was only after Joshua Tree that we started to make money," he says. That's a surprise—Joshua Tree, which came out in<br />

1987 and sold 14 million copies, was <strong>U2</strong>'s fifth album. The world figured they were rich long before that. "After Joshua Tree<br />

we invested a lot <strong>of</strong> money into Rattle and Hum. So we saw a lot <strong>of</strong> money but never made any. It was put back into the movie.<br />

I remember walking away with about twenty thousand dollars. That was the money that was there when I arrived home from<br />

the Joshua Tree tour. There was more later on. I remember going down to Waterford. I had been saving for years and years to<br />

buy myself a Harley. That was the first real material thing I ever bought. The money came in very, very slowly. It wasn't<br />

immediate at all. It wasn't like we did the Joshua Tree tour and then someone gave me five million dollars and said,<br />

[18]<br />

"There you are, son, go with it.' It wasn't like that at all, it was a very slow thing."<br />

What was the reaction <strong>of</strong> friends and family when they assumed, perhaps before it was true, "Oh, Larry's a millionaire now"?<br />

Does everybody wait for you to pick up the check at dinner?<br />

"To a limited degree," he says. "It's only recently that it's become a major issue, 'cause there is publicity about it, a lot <strong>of</strong> people<br />

talk about it. What disturbs me most is that people figure, 'Hey, look, a hundred quid to me is two weeks wages. It's nothing to<br />

you!' I find that incredibly <strong>of</strong>fensive. That's jumping to conclusions. It's just taking advantage. That's the biggest thing that's<br />

affected the way I feel about some people. I find there are two very distinctly different reactions. There's those people who say, 'I<br />

don't give a damn what you do, I buy my round, you buy your round. We're friends. I expect nothing from you.' And there's the<br />

other ones. It's hard because the people you grow up with are generally people who don't have any money. They work in banks or<br />

they're electricians and they don't make as much. I think they should be responsible for themselves and not take advantage. I think<br />

it's lack <strong>of</strong> respect for themselves. I certainly don't respect them."<br />

I ask why Larry told Bono, during the last tour, that he didn't like what <strong>U2</strong> had become.<br />

"It had become very serious, very hard work. And just no fun. It was nothing to do with music. It was to do with getting up and<br />

going to work. Because we take care <strong>of</strong> a lot <strong>of</strong> our own business, we spend a lot <strong>of</strong> time in meetings. We've always done that. On<br />

the stage it was good, but it was very intense and was very hard work. You were grimacing because you were stressed. I<br />

remember coming <strong>of</strong>f that tour and feeling, '<strong>If</strong> this is what it is, I really don't want to do it anymore, I can't do this anymore.'<br />

"It was just stressful on a musical level. I suppose we had realized that we weren't as capable <strong>of</strong> plugging into other people's worlds<br />

—like Â. Â. King's—as we'd hoped. And I certainly found it was nothing to do with where I was coming from. I'm glad to have<br />

had the experience, but that's it. I come from a different world."<br />

Well, I say, the stretch in Berlin wasn't exactly a load <strong>of</strong> laughs.<br />

"No," Larry says. "It was suddenly trying to unplug that different world <strong>of</strong> Rattle and Hum and plug into another one. That's very<br />

hard to do. When we plugged into Rattle and Hum we'd lost touch with where it<br />

[19]<br />

was we had come from—which is trying to find new ways. Some people were quicker at finding the route than others, and it<br />

caused immense strain within the band. Because for the first time in the band there was no consensus musically. Whereas in the<br />

past, although everyone might not agree, there was some sort <strong>of</strong> understanding <strong>of</strong> what was going on. This time there was no<br />

understanding. No one knew what the fuck anyone else was talking about. That was the basis <strong>of</strong> all those problems."<br />

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Nitehawk/Desktop/u2-book.htm (13 <strong>of</strong> 257)16/07/2004 08:38:29

Ñêàíèðîâàíèå: ßíêî Ñëàâà. <strong>U2</strong>. <strong>U2</strong> at the End <strong>of</strong> the World by Bill Flanagan<br />

All <strong>of</strong> what the band has been going through gets thrown into Bono's lyrics. It is only in the final weeks before the album is<br />

due to be delivered to the record company that most <strong>of</strong> it comes together. "We tend to spend 90 percent <strong>of</strong> the time on 30<br />

percent <strong>of</strong> the material," Adam explains, "and the rest happens incredibly quickly,"<br />

<strong>U2</strong> bring in their old producer Steve Lillywhite, as well as Eno, Flood, and Lanois, and get everyone mixing. Different<br />

producers mix the same songs and then present them to the band, who pick one (or worse, pick aspects <strong>of</strong> each and ask one <strong>of</strong><br />

the exhausted producers to combine them). What emerges is a weird juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> frantic sound (influenced by techno, hiphop,<br />

and other urban pop trends, but grounded in solid song structures) and introspective lyrics about the tension between<br />

domestic life and the lure <strong>of</strong> the outside world's adventures. The music, the sound itself, is so full <strong>of</strong> life and electricity that it's<br />

easy to understand what's seducing the lyricist away from his responsibilities at home; the music conveys how much fun there<br />

is to be had out there in the world <strong>of</strong> discos, boom boxes, rock concerts, and raves. The words may reveal the guilt and concern<br />

going through the singer's head, but the music demonstrates the fun and exuberance racing through his bloodstream.<br />

The first song—"Zoo Station"—blasts open with a barrage <strong>of</strong> electronic sounds and distortion. Bono's voice is processed so<br />

heavily, it barely sounds human. <strong>If</strong> you strain you can make out what he's saying:<br />

"I'm ready, ready for what's next."<br />

The music conjures up an environment like Times Square or Piccadilly Circus at 11 p.m. on a July Saturday. It's full <strong>of</strong><br />

pushing and shoving, hip-hop samples, loud arguments, bursting images, and screaming guitars. Some <strong>of</strong> Bono's lyrics<br />

sound like they were read <strong>of</strong>f the T-shirts in an all-night souvenir shop ("Don't let the bastards grind you down," "A woman<br />

needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle"), like they are<br />

[20]<br />

being recited by a man in that late-night state <strong>of</strong> sensory overload where you babble phrases you just overheard.<br />

The central character that emerges on this expedition through urban perdition is a man messing up his secure home life by<br />

charging out into the night's temptations. The album is full <strong>of</strong> romantic and spiritual anguish, <strong>of</strong> the bargains made between<br />

couples and the recriminations they throw at each other when those deals are breached. In this context, when Bono sings, "We're<br />

one, but we're not the same," it sounds less like a comfort than an excuse.<br />

One good side effect <strong>of</strong> Bono's bad habit <strong>of</strong> leaving all his lyrics in flux until the last minute is that by the time he puts the final<br />

vocals on an album there is usually a narrative coherence to the whole thing. Your old English teacher might tell you that this<br />

results in a novelistic cohesiveness. Certain members <strong>of</strong> <strong>U2</strong> who have nothing left <strong>of</strong> their fingernails might call it the result <strong>of</strong> a<br />

long intellectual constipation finally ended by a verbal diarrhea. I myself would like to point out that in this case it results in an<br />

album-long metaphor <strong>of</strong> the moon as a dark woman who seduces the singer away from his virtuous love, the sun. In the middle <strong>of</strong><br />

Side Two the singer, lying in the gutter in a vain attempt to throw his arms around the world, looks up and sees the sun rising. He<br />

asks, "How far are you gonna go before you lose your way back home?" Then he starts crawling home, exhausted, elated,<br />

ashamed, satisfied, and nursing a bloody nose.<br />

That would be an easy place for the album to end, and in the Andy Capp world <strong>of</strong> most rock & roll, that's usually where we fade<br />

out. <strong>U2</strong> doesn't let their listeners <strong>of</strong>f the hook so easily. The darkness <strong>of</strong> the doubts they've raised cannot be exorcised by a night<br />

on the town. The last three songs face the big issue <strong>of</strong> how couples begin to reconcile the suffering they force on each other. In<br />

"Ultra Violet" the singer pleads with his love to light his way home, only to find that "the day is as dark as the night is long." The<br />

couple crawl into bed together, unable to sleep. He marvels at his own hypocrisy: "I must be an acrobat to talk like this and act<br />

like that." They decide that if they can't sleep maybe they can speak their dreams out loud and (Bono's quoting Delmore Schwartz<br />

here) "begin responsibilities." The album fades out with the conclusion that "Love Is Blindness," the inability to distinguish day<br />

from night.<br />

This is <strong>U2</strong> in Nighttown, an X ray <strong>of</strong> four men who spent their<br />

[21]<br />