Download - Downbeat

Download - Downbeat

Download - Downbeat

- TAGS

- download

- downbeat

- downbeat.com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

DOWNBEAT CHRISTIAN SCOTT // KURT ROSENWINKEL // ROBERT GLASPER // FAVORITE BIG BAND ALBUMS<br />

APRIL 2010<br />

DownBeat.com<br />

$4.99<br />

0 09281 01493 5<br />

04<br />

APRIL 2010 U.K. £3.50

April 2010<br />

VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 4<br />

President Kevin Maher<br />

Publisher Frank Alkyer<br />

Editor Ed Enright<br />

Associate Editor Aaron Cohen<br />

Art Director Ara Tirado<br />

Production Associate Andy Williams<br />

Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens<br />

Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser<br />

ADVERTISING SALES<br />

Record Companies & Schools<br />

Jennifer Ruban-Gentile<br />

630-941-2030<br />

jenr@downbeat.com<br />

Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools<br />

Ritche Deraney<br />

201-445-6260<br />

ritched@downbeat.com<br />

Classified Advertising Sales<br />

Sue Mahal<br />

630-941-2030<br />

suem@downbeat.com<br />

OFFICES<br />

102 N. Haven Road<br />

Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970<br />

630-941-2030<br />

Fax: 630-941-3210<br />

www.downbeat.com<br />

editor@downbeat.com<br />

CUSTOMER SERVICE<br />

877-904-5299<br />

service@downbeat.com<br />

CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Senior Contributors:<br />

Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel<br />

Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley;<br />

Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak,<br />

Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman<br />

Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl<br />

Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan:<br />

John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk;<br />

New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman,<br />

Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D.<br />

Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer Odell, Dan<br />

Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian,<br />

Michael Weintrob, Kevin Whitehead; North Carolina: Robin Tolleson;<br />

Philadelphia: David Adler, Shaun Brady, Eric Fine; San Francisco: Mars<br />

Breslow, Forrest Bryant, Clayton Call, Yoshi Kato; Seattle: Paul de Barros;<br />

Tampa Bay: Philip Booth; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph,<br />

Bill Shoemaker, Michael Wilderman; Belgium: Jos Knaepen; Canada:<br />

Greg Buium, James Hale, Diane Moon; Denmark: Jan Persson; France:<br />

Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Detlev Schilke, Hyou Vielz; Great Britain:<br />

Brian Priestley; Japan: Kiyoshi Koyama; Portugal: Antonio Rubio;<br />

Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert.<br />

Jack Maher, President 1970-2003<br />

John Maher, President 1950-1969<br />

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: Send orders and address changes to: DOWNBEAT, P.O. Box 11688,<br />

St. Paul, MN 55111–0688. Inquiries: U.S.A. and Canada (877) 904-5299; Foreign (651) 251-9682.<br />

CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Please allow six weeks for your change to become effective. When<br />

notifying us of your new address, include current DOWNBEAT label showing old address.<br />

DOWNBEAT (ISSN 0012-5768) Volume 77, Number 4 is published monthly by Maher Publications,<br />

102 N. Haven, Elmhurst, IL 60126-3379. Copyright 2010 Maher Publications. All rights reserved.<br />

Trademark registered U.S. Patent Office. Great Britain registered trademark No. 719.407. Periodicals<br />

postage paid at Elmhurst, IL and at additional mailing offices. Subscription rates: $34.95 for one<br />

year, $59.95 for two years. Foreign subscriptions rates: $56.95 for one year, $103.95 for two years.<br />

Publisher assumes no responsibility for return of unsolicited manuscripts, photos, or artwork.<br />

Nothing may be reprinted in whole or in part without written permission from publisher. Microfilm<br />

of all issues of DOWNBEAT are available from University Microfilm, 300 N. Zeeb Rd., Ann Arbor,<br />

MI 48106. MAHER PUBLICATIONS: DOWNBEAT magazine, MUSIC INC. magazine, UpBeat Daily.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send change of address to: DownBeat, P.O. Box 11688, St. Paul, MN 55111–0688.<br />

CABLE ADDRESS: DownBeat (on sale March 16, 2010) Magazine Publishers Association<br />

Á

DB Inside<br />

Departments<br />

8 First Take<br />

10 Chords & Discords<br />

13 The Beat<br />

19 European Scene<br />

20 Caught<br />

22 Players<br />

Danny Grissett<br />

Dana Hall<br />

Luis Bonilla<br />

Steve Colson<br />

47 Reviews<br />

74 Master Class<br />

76 Transcription<br />

78 Jazz On Campus<br />

82 Blindfold Test<br />

Dafnis Prieto<br />

6 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

JOEY L.<br />

Features<br />

Robert Glasper<br />

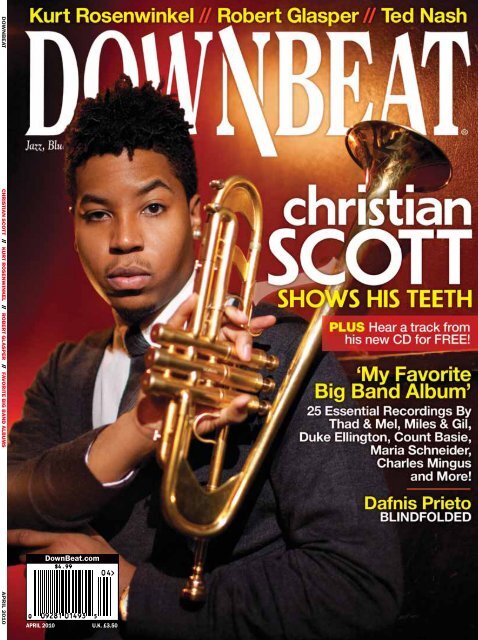

26 Christian Scott<br />

Shows His Teeth | By Jennifer Odell<br />

Christian Scott’s appreciation for the ability of music to tell stories and to make<br />

social commentary is rare. The trumpeter’s company, like his music, has a comfortable<br />

intensity to it—an easy warmth that wins you over even when he’s on a<br />

mission to change your mind about something. Though gracious and polite,<br />

Scott presents his point of view with the same confident authority he puts into<br />

his live shows. And even when what he says rubs folks the wrong way, his honest<br />

expression comes with a grain of erudite salt.<br />

32 Kurt Rosenwinkel<br />

Making Magic<br />

By Ted Panken<br />

36 Robert Glasper<br />

Iconic Impulses<br />

By John Murph<br />

40 ‘My Favorite Big Band Album’<br />

25 Essential Recordings<br />

By Frank-John Hadley<br />

68 Musicians’ Gear Guide<br />

Great Finds From The<br />

NAMM Show 2010<br />

50 Philly Joe Jones 50 Agustí Fernández/Barry Guy 54 Christian Wallumrød 60 Paul Motian<br />

36<br />

Cover photography by Jimmy Katz. Special thanks to Blue Smoke and Jazz Standard in New York City for their generosity in letting DownBeat shoot on location.

8 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

First Take<br />

Organic Orchestration<br />

by Ed Enright<br />

This issue of DownBeat,<br />

featuring Christian Scott on<br />

the cover, came together<br />

over a period of several<br />

months. In fact, it was a full<br />

year ago that we originally<br />

planned to give Scott top<br />

billing in the magazine, only<br />

to be pre-empted by the<br />

death of Freddie Hubbard.<br />

But being bumped from his<br />

cover spot turned out to be<br />

not such an unfortunate<br />

thing for Scott, whose highly<br />

anticipated CD Yesterday<br />

You Said Tomorrow, the<br />

most important of his young<br />

career, hasn’t been ready for<br />

commercial release until Christian Scott<br />

now, anyway.<br />

During his interview with writer Jennifer Odell, Scott emphasizes his<br />

fondness for the sounds and social vibes of the 1960s and explains how<br />

that mindset inspired and shaped the 10-song collection, recorded at the<br />

renowned Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, N.J., and engineered<br />

by Rudy Van Gelder—the man largely responsible for the emergence of<br />

the legendary “Blue Note sound,” which has graced hundreds of jazz<br />

albums dating back to the 1960s. Among those are several landmark sides<br />

recorded by none other than Hubbard himself.<br />

Research for our feature story on Kurt Rosenwinkel began late last<br />

summer, when the guitarist was just beginning the recording sessions that<br />

eventually led to the release of his new CD, Standards Trio: Reflections.<br />

As Rosenwinkel told writer Ted Panken, the resulting ballads-driven<br />

album emerged over the course of the sessions and developed gradually<br />

over time, only to reveal itself in the later stages of editing, after all the<br />

dozens of takes were completed.<br />

The organic way these artists’ recording projects and writers’ feature<br />

articles unfold and take shape over time reminds me of the way a composer<br />

or orchestrator crafts a musical chart. Which brings us to Frank-John<br />

Hadley’s article “My Favorite Big Band Album,” an ambitous piece that<br />

required months and months of reporting as Hadley polled nearly 200<br />

musicians around the world about their top five picks within the genre.<br />

With so much material, we had a tough time deciding where to draw the<br />

line (at the top 25 albums) and which of the insightful quotes to use or discard.<br />

There was no way we could print all the responses we received in the<br />

space allowed, so I’ll take this opportunity to add some background on the<br />

results published on pages 40–45.<br />

Hadley reports that a Duke Ellington record appeared on 75 percent of<br />

respondents’ lists—47 different recordings, including a few compilations.<br />

Count Basie was the second most popular choice, with 98 picks going to<br />

30 albums. Sun Ra would have placed if there had been any sort of agreement<br />

over what one record of his most persuasively explored the cosmos—11<br />

albums were chosen. Just a short drop from the top-25 tier were<br />

Basie’s The Original Decca Recordings, Miles Davis & Gil Evans’<br />

Sketches Of Spain, George Russell’s New York, N.Y., Stan Kenton’s City<br />

Of Glass and—a surprise—Bill Potts’ The Jazz Soul Of Porgy & Bess.<br />

We hope you find this issue of DownBeat to read and play out like a<br />

great big band arrangement, one that has evolved in proper time, where<br />

every detail falls into place and forms a bigger picture complete with<br />

information, perspective and a certain intangible edge we like to call<br />

“swing.” DB<br />

JIMMY KATZ

Chords & Discords<br />

Jamal’s Constellation<br />

A five star rating for your March issue’s<br />

cover, feature and photos. And 100 stars for<br />

pianist Ahmad Jamal!<br />

Dennis Hendley<br />

Milwaukee, Wis.<br />

Offensive Language<br />

I was surprised by Eldar Djangirov’s offensive<br />

language in DownBeat’s “The Question Is…”<br />

section (March). His use of the word “retarded”<br />

to describe something negative regarding<br />

a jazz video game is just plain juvenile. This<br />

sort of language should be completely<br />

removed from our vocabulary as a descriptive<br />

for things that are sub-par. It is akin to using<br />

the “n-word.” As jazz musicians, we’re supposed<br />

to be hipper than that, and be sensitive<br />

to different abilities, races and cultures. “Boy<br />

genius” is a good descriptive for Eldar.<br />

Emphasis on the “boy.”<br />

Bennett Olson<br />

bennettolson@wi.rr.com<br />

Pure Duke<br />

As one who has listened deeply to George<br />

Duke, I gained insight into his harmonic<br />

vocabulary when I recently heard Bela<br />

Bartok’s “Second Concerto For Piano.” The<br />

second movement (Adagio) is pure Duke! It<br />

would have been great to hear his reaction to<br />

this piece in February’s Blindfold Test.<br />

Doug Parham<br />

Lancaster, Calif.<br />

Don’t Slight The South<br />

John Ephland’s review of Steve Hobbs’ Vibes,<br />

Straight Up (“Reviews,” March) contains several<br />

oversights. Primarily, it slights the very<br />

spirit of the album: songs from or about the<br />

Southern United States. Thankfully, the entire<br />

quartet captures that spirit eloquently.<br />

Dean Arnold<br />

arnie60@hotmail.com<br />

Descriptive Praise<br />

I love how DownBeat not only has a way to<br />

appreciate the music through words but also<br />

to get in-depth with the analyses through the<br />

transcription page. Keep it coming!<br />

Irina Makarenko<br />

danielmandrychenko@yahoo.com<br />

Shallow Appraisal<br />

I was disappointed in your “Best CDs of the<br />

2000s” issue (January). A bare list of past 4.5and<br />

5-star ratings without current critical<br />

appraisal is not worth taking seriously.<br />

Paul Chastain<br />

cathpaul@bellsouth.net<br />

Burrell, Grimes Shine<br />

Eric Fine’s review describing the Memorial<br />

Tribute to Rashied Ali in Philadelphia shows<br />

no awareness of how improvised music<br />

works (“Caught,” March). That Fine would<br />

characterize Dave Burrell’s piano work as<br />

“undistinguished” and question Henry<br />

Grimes’ violin technique is a measure of<br />

Fine’s lack of sensitivity, making me wonder<br />

if he had any idea of the scope of Ali’s<br />

influence in the first place.<br />

Lyn Horton<br />

Worthington, Mass.<br />

Keep Trad Alive!<br />

After I read through the October 2009 issue, I<br />

came back to Michael Bourne’s intro to “Why<br />

Jazz Endures” and his reference to Louis<br />

Armstrong’s solo intro to “West End Blues.”<br />

Steven Bernstein’s comment that “jazz is<br />

everywhere now” is the reason I’m writing.<br />

There are still musicians, vocalists and listeners<br />

who are devoted followers of traditional<br />

jazz. There are jazz festivals all over promoting<br />

that kind of music. The music of Louis<br />

Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton and Bessie<br />

Smith is not dead. There are jazz programs<br />

that teach people to play that kind of music. It<br />

is my hope that you will, in the future, devote<br />

more space to trad jazz.<br />

Leon Friedman<br />

mfried3248@cox.net<br />

Corrections<br />

Pianist Bill O’Connell was misidentified in<br />

the review of Hobbs’ CD Vibes, Straight Up.<br />

Violinist Joe Kennedy Jr. was misidentified<br />

in the feature on Ahmad Jamal (March).<br />

DownBeat regrets the errors.<br />

Have a chord or discord? E-mail us at editor@downbeat.com.

Game<br />

Changer<br />

Saxophonist Ted Nash’s<br />

disc marks new direction<br />

for the Jazz at Lincoln<br />

Center Orchestra<br />

At the beginning of March, the Jazz at Lincoln<br />

Center Orchestra (JLCO) set out on a tour much<br />

like any other—a 21-concert, 19-city sojourn<br />

that launched in Washington, D.C., and would<br />

take the group across the United States. But this<br />

event signified an important transition in the<br />

Jazz at Lincoln Center business model.<br />

For the first time since Big Train, from<br />

1999, JLCO was backing a new CD, Portraits<br />

In Seven Shades, a kaleidoscopic suite by saxophonist<br />

Ted Nash, on its eponymous signature<br />

label, also brand-new, to be distributed in both<br />

physical and digital form through the Orchard, a<br />

publicly traded mega-aggregator of independent<br />

labels that holds close to 14,000 jazz titles. Not<br />

inconsequentially, Portraits is the first-ever<br />

JLCO release devoted to original music by a<br />

band member not named Wynton Marsalis<br />

(Don’t Be Afraid [Palmetto], from 2003, comprises<br />

Ronald Westray’s arrangements of<br />

Charles Mingus repertoire).<br />

“The band is an institution, and to be viable,<br />

the institution has to grow,” Marsalis said. “I<br />

was one of the founders, so at first it was based<br />

on me. As we’ve refined the sound and concept,<br />

we’ve incorporated more people into our<br />

voice.”<br />

Partly due to this policy, the orchestra’s<br />

identity is less dependent on the presence of its<br />

most celebrated figure, who positions himself<br />

not facing the band, but in the trumpet line. To<br />

wit, JLCO didn’t skip a beat on the several<br />

occasions between 2004 and 2006 when a<br />

recurring lip inflammation sent Marsalis to the<br />

sidelines, and it has sold out several Rose<br />

Theater concerts—most recently a Carlos<br />

Henriquez-led homage to Dizzy Gillespie and<br />

Tito Puente—in which he did not participate.<br />

During a 2005 tour of Mexico, Marsalis<br />

commissioned Nash—whose prior contributions<br />

to the band book included charts on such<br />

repertoire as “My Favorite Things,” “Tico,<br />

INSIDE THE BEAT<br />

14 Riffs<br />

19 European<br />

Scene<br />

20 Caught<br />

22 Players<br />

Saxophonist Ted Nash performing with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra<br />

Tico,” Wayne Shorter’s “Fe-Fi-Fo-Fum,” and<br />

Ornette Coleman’s “Kaleidoscope” and “Una<br />

Muy Bonita”—to compose a “big form piece”<br />

around a theme of his choosing. Nash decided<br />

to base each chart on his response to a different<br />

painting from the collections of the Museum of<br />

Modern Art, with which JLCO has fostered a<br />

reciprocal relationship. Allowed to absorb<br />

MOMA’s holdings on various off-hours visits,<br />

Nash eventually winnowed down to works by<br />

Claude Monet, Salvador Dali, Henri Matisse,<br />

Pablo Picasso, Vincent Van Gogh, Marc<br />

Chagall and Jackson Pollock.<br />

In imparting to each movement its own flavor,<br />

Nash wields a vivid palette of orchestral<br />

and rhythmic color. On “Monet,” a lilting,<br />

impressionistic work in 3/4, he juxtaposes<br />

higher-pitched instruments with the bass,<br />

extracting beautiful colors from the trumpets<br />

by deft use of various mutes. Violin and accordion<br />

infuse “Chagall” with a klezmer feeling,<br />

FRANK STEWART/JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER<br />

April 2010 DOWNBEAT 13

Riffs<br />

Wild Wertico: Drummer Paul Wertico<br />

is now hosting a radio show, “Paul<br />

Wertico’s Wild World of Jazz,” on<br />

Chicago radio station 87.7FM, WLFM.<br />

Although a smooth-jazz station,<br />

Wertico’s show will include traditional<br />

and other formats. Details: wlfm877.com<br />

Bolden Tribute: Composer Dave Lisik<br />

has created a 10-movement orchestral<br />

work celebrating the life of Buddy<br />

Bolden. The recording, Coming Through<br />

Slaughter (Galloping Cow), features Tim<br />

Hagans, Donny McCaslin and Luis<br />

Bonilla. Details: gallopingcowmusic.com<br />

Clayton Moves: Pianist Gerald Clayton’s<br />

CD, Two-Shade, which had been available<br />

through ArtistShare, has been rereleased<br />

through EmArcy.<br />

Details: umusic.com<br />

Brother Ray Returns: Ray Charles’<br />

1960s and ’70s jazz albums have been<br />

reissued as a two-disc compilation,<br />

Genius + Soul = Jazz (Concord). The collection<br />

includes the 1961 album of the<br />

same name, as well as the followups,<br />

My Kind Of Jazz, Jazz Number II and My<br />

Kind Of Jazz Part 3.<br />

Details: concordmusicgroup.com<br />

Adult Trad Camp: The first annual<br />

New Orleans Traditional Jazz Camp<br />

For Adults will be held Aug. 1–6 in the<br />

city’s Bourbon Orleans Hotel. Along<br />

with lectures and lessons, the camp<br />

will include a birthday celebration for<br />

Louis Armstrong at Preservation Hall.<br />

Faculty includes trumpeter Connie<br />

Jones and vocalist Banu Gibson.<br />

Details: neworleanstradjazzcamp.com<br />

RIP, Dankworth. British saxophonist Sir<br />

John Dankworth died on Feb. 6. He was<br />

82. Dankworth, who worked with Nat<br />

King Cole, Oscar Peterson and Ella<br />

Fitzgerald, also composed the scores for<br />

numerous British films and television<br />

shows. His wife, and performing partner,<br />

singer Cleo Laine, survives him.<br />

14 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

while he opens “Picasso” with a distillation of<br />

a Spanish progression, sandwiching a long section<br />

in which Nash transfuses Cubist aesthetics<br />

into notes and tones by deploying McCoy<br />

Tyner-esque fourths as “an integral component<br />

of the thematic material, the harmony and the<br />

voicings.”<br />

On “Pollock,” Nash emulated the abstract<br />

expressionist’s paint-splattering techniques by<br />

conjuring piano fragments and coalescing them<br />

into a line that evokes a jagged Herbie Nichols<br />

theme, while giving the blowing section an<br />

open Ornette Coleman-like quality with background<br />

passages composed of unassigned noteheads.<br />

He conjures the melted clocks and<br />

parched mise en scene of Salvador Dali’s “The<br />

Persistence of Memory” with a 13/8 groove,<br />

melodic tonalities that evoke what he calls “a<br />

lost creature searching,” and simultaneous<br />

improvised solos on trumpet and alto on which<br />

the lines flow one into the other.<br />

Like Marsalis, Nash, now 50, blossomed<br />

early, a “young lion” before the term became<br />

marketing vernacular. The son of eminent Los<br />

Angeles studio trombonist Dick Nash and the<br />

namesake nephew of studio woodwind player<br />

Ted Nash, he moved to New York at 18, after<br />

spending much of his teens working for Lionel<br />

Hampton, Quincy Jones, Don Ellis and Louis<br />

Bellson. Before signing up with the Lincoln<br />

Center Jazz Orchestra, as it was known until<br />

2007, Nash accumulated a resume marked by<br />

consequential stints with the Mel Lewis<br />

Orchestra, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Gerry Mulligan,<br />

the Carnegie Hall Big Band and various configurations<br />

of the New York’s Jazz Composers’<br />

Collective. On Portraits, Nash draws vocabulary<br />

from all these experiences, not neglecting<br />

the predilections of each JLCO member when<br />

they improvise and play ensemble.<br />

“JLCO has a distinctive quality, not necessarily<br />

in the older styles of music that we’ve<br />

received the greatest exposure for playing, but<br />

in the stuff we’re writing now and play in New<br />

York or on the road,” Nash said. “With Mel,<br />

we’d swing on Thad Jones and Bob<br />

Brookmeyer, and then open up the solos so it<br />

became a kind of quartet. Here the solos are less<br />

extended, and seem more to address the music;<br />

everyone is committed to making a statement<br />

from beginning to end of a piece. The ensemble<br />

becomes almost its own voice—not the clean<br />

style of the ‘New Testament’ Basie band, but<br />

more like Ellington’s approach, with different<br />

timbres, different individuals.<br />

“There’s a soulful feeling, a support system<br />

I’ve never felt before, like a quest for truth,”<br />

Nash continued. “We cover more ground than<br />

any band I’ve been with, too—Wynton’s opuses<br />

like All Rise and Congo Square, stuff that’s<br />

completely free and out there, stuff that’s the<br />

very beginning of jazz.”<br />

Perhaps the sprawling, impossible-to-pinpoint<br />

scope of JLCO’s repertoire is a reason<br />

why it has not translated its enviable worldwide<br />

visibility and Marsalis’ enormous prestige into<br />

strong unit sales on prior recording projects.<br />

The institution hopes to ameliorate this situation<br />

in their partnership with the Orchard by using<br />

its international digital network—it services 700<br />

stores and has representatives in 25 countries—<br />

to effectively target their buyers. With Portraits,<br />

this entailed securing placements on such usualsuspect<br />

store pages as iTunes, eTunes, Amazon<br />

and bn.com, as well as international outlets like<br />

Fnac and Virgin. Furthermore, in the weeks<br />

leading up to the release, Nash did considerable<br />

promotional activity, while the Orchard conducted<br />

outreach and contests via social media—<br />

email lists, Facebook, Twitter, the Jazz at<br />

Lincoln Center and MOMA subscriber bases.<br />

“Everything in the digital world works the<br />

same way,” said Richard Gottehrer, the<br />

Orchard’s co-founder and chief creative officer,<br />

who knew the ancien regime as a songwriter<br />

(“My Boyfriend’s Back”), producer (“Hang On<br />

Sloopy”), label-owner (Sire) and talent manager<br />

(Blondie, The Go-Gos, Joan Armatrading).<br />

“You try to engage the fans, and the fans<br />

become the vehicle for spreading the word as<br />

opposed to radio.”<br />

“We’re classic long-tail territory,” said<br />

Adrian Ellis, JLC’s executive director. “Jazz is<br />

niche music, and clearly, the wider the distribution<br />

of your catalog, the greater chance that<br />

your fans around the world can find it.”<br />

Although the label’s primary purpose is to<br />

exploit its massive archive, comprising every<br />

JLC concert over the past two decades, JLC<br />

intends to make full use of its on-site studio<br />

and recording facilities to document new work<br />

going forward in a timely manner. Ellis estimates<br />

four to five releases each year; the format<br />

decisions will be key to perceived sales<br />

potential.<br />

Neither Ellis nor Ken Druker, JLC’s director<br />

of intellectual property, were prepared to state<br />

what the next releases would be.<br />

“We’re working through the rights issues,<br />

the mixing and mastering,” Ellis said. “The<br />

Orchard appears to offer an easy, cost-effective<br />

distribution route for getting things out at an<br />

appropriate pace.”<br />

What is clear is that Jazz at Lincoln Center is<br />

in the digital marketplace for keeps.<br />

“I believe in the ultimate integration of all<br />

aspects of what you do,” said Marsalis, whose<br />

own separate deal with the Orchard stipulates<br />

that they will co-produce as well as distribute<br />

his projects. “We’re a non-profit, and we create<br />

nothing but content all the time. We have<br />

an opportunity to use that content to expand<br />

our audience, to turn people around the world<br />

on to jazz, and raise money. Our dream was to<br />

have a space—I call it a ‘cloud’—where<br />

there’s radio, video and digital content, which<br />

can be streamed, downloaded, or purchased.<br />

The money we make can go directly back into<br />

providing some type of public service.”<br />

—Ted Panken

Germany’s Jazzahead Builds On International Networks<br />

Although Germany’s Jazzahead started back in<br />

2006, two years before bankruptcy shuttered the<br />

International Association of Jazz Educators<br />

conference, this organization now stands poised<br />

as one of the largest jazz business meetings on<br />

the planet. Though smaller than the IAJE event<br />

and lacking the emphasis on jazz education, this<br />

year’s installment of Jazzahead, to be held in<br />

Bremen April 22–25 in the city’s Congress<br />

Centrum, has become an increasingly valuable<br />

platform for jazz professionals of all stripes to<br />

meet face-to-face. There’s a large exhibition<br />

hall, conferences and symposiums, and a mini<br />

festival with more than 40 short concerts, with a<br />

clear focus on young European musicians (program<br />

information is listed on jazzahead.de).<br />

The event is the brainchild of Peter Schulze,<br />

a veteran of German radio and a respected festi-<br />

Norma Winstone<br />

performing at the<br />

2009 Jazzahead<br />

val organizer, and Hans Peter Schneider, director<br />

of Messe Bremen, the city’s trade organization.<br />

Schulze had been lobbying to create a<br />

German Jazz Meeting, an idea inspired by the<br />

Dutch Jazz Meeting as a showcase for jazz talent<br />

from the Netherlands, but it came to life as<br />

something bigger.<br />

“The basic idea of Jazzahead is that we<br />

should put jazz at the center,” Schulze said.<br />

“These kinds of exhibitions, like Womex,<br />

Midem, or Popkomm—they all had jazz at a<br />

certain time, but it kind of faded out after a couple<br />

of editions. We wanted to put jazz in the<br />

center to see what we can do from inside.”<br />

In order to open up potential audiences,<br />

Schulze has also presented some tangential<br />

symposiums that borrow ideas from jazz,<br />

despite being worlds apart.<br />

“This past year we had a medical symposium<br />

with 150 doctors on the neurological perception<br />

of improvisation—how it relates to neurological<br />

processes,” he said. “They don’t relate<br />

to jazz at all, but they become a part of it.”<br />

Still, networking remains a primary focus.<br />

“For us booking agents living high up in the<br />

mountains of Norway, it’s good that there is a<br />

conference where we can attend and meet all<br />

COURTESY JAZZAHEAD<br />

these people we only have spoken to on the<br />

phone,” said Per-Kristian Rekdal, of the Oslo<br />

booking agency Mussikprofil. “It is often easier<br />

to be open and honest when you first have met<br />

people, and then we can speak more freely and<br />

relaxed next time.”<br />

Huub van Riel, who programs Amsterdam’s<br />

prestigious Bimhuis, concurs: “Meeting many<br />

professionals face-to-face was valuable and productive.<br />

I had a number of first time meetings,<br />

both with relatively new contacts and some I’ve<br />

worked with for many years.”<br />

Last year’s event attracted about 5,000 attendees<br />

from more than 30 countries, up from<br />

3,000 in 2006.<br />

“We do not want to expand it too much,”<br />

Schulze said. “You have to control your program.<br />

And you hardly hear any mainstream<br />

music here, which is what so many festivals are<br />

all about.” —Peter Margasak<br />

April 2010 DOWNBEAT 15

EUROPEAN SCENE<br />

By Peter Margasak<br />

German impresario Ulli Blobel<br />

has long been an important,<br />

sometimes controversial, figure<br />

in European jazz—concert promoter,<br />

artist manager, booking<br />

agent, label owner, record shop<br />

proprietor and distributor—<br />

stretching back four decades. He<br />

started booking jazz concerts in<br />

1969 in his hometown of Peitz,<br />

south of Berlin, in what was<br />

then East Germany. Occasional<br />

concerts grew into Jazzwerkstatt<br />

(Jazz Workshop) Peitz, which<br />

began in 1979. It’s the biggest<br />

festival in Germany outside of<br />

Berlin’s annual event. Blobel<br />

was presenting between six and<br />

eight concerts annually in addition<br />

to the workshop, bringing<br />

in artists from throughout the<br />

continent.<br />

“Everything was not always<br />

in agreement with the official<br />

cultural politics of the Communist<br />

dictatorship, and sometimes<br />

it led to problems, sometimes<br />

not,” he said.<br />

In 1984, Blobel moved on. In<br />

an unusual situation, the government<br />

allowed him to move<br />

to Wuppertal, in West Germany.<br />

“The Jazzwerkstatt Peitz was<br />

forbidden by the Communist<br />

government,” Blobel said.<br />

“Our outdoor festival was, for<br />

their eyes, too big. It had developed<br />

into a festival with 3,000<br />

visitors.”<br />

Blobel worked extensively<br />

with heavies like Peter Brötzmann<br />

and Peter Kowald, and<br />

began ITM Records—the source<br />

of his controversy. Many artists<br />

have accused him of releasing<br />

music without proper agreements—notably,<br />

Anthony<br />

Braxton—but as he told writer<br />

Francesco Martinelli for the<br />

Web zine Point of Departure a<br />

couple of years ago, subsequent<br />

court cases exonerated<br />

him. And it’s his current work<br />

that’s indisputably valuable.<br />

After spending most of the<br />

last two decades working in<br />

record distribution, he returned<br />

to a more direct involvement,<br />

with Jazzwerkstatt Berlin-<br />

Brandenburg. He started the<br />

organization in 2007 and since<br />

then he produces around 120<br />

concerts each year along with<br />

three festivals—including the<br />

acclaimed European Jazz<br />

Jamboree. More recently he<br />

opened the Jazzwerkstatt +<br />

Klassik record store, which<br />

includes a cafe that presents<br />

concerts. But to American listeners<br />

his most valuable service<br />

has been the Jazzwerkstatt<br />

label, which has quickly become<br />

a crucial documenter of Berlin’s<br />

thriving contemporary scene<br />

(although the label has also<br />

released superb archival work<br />

from Blobel’s Peitz days).<br />

The main thrust is on younger<br />

musicians, from staunch avantgardists<br />

to more mainstream<br />

players, but there is a focus on<br />

veterans (Rolf Kühn, Ulrich<br />

Gumpert and Alexander von<br />

Schlippenbach) intersecting with<br />

their artistic heirs. He’s also put<br />

out fine recordings by plenty of<br />

non-Germans including David<br />

Murray, Max Roach and Urs<br />

Jazz’s roots in Europe are strong. This column looks at<br />

the musicians, labels, venues, institutions and events<br />

moving the scene forward “across the pond.” For<br />

questions, comments and news about European jazz,<br />

e-mail europeanscene@downbeat.com.<br />

Longtime Jazz Impresario Captures Berlin’s Musical Evolutions<br />

Clark Terry Snags Lifetime<br />

Achievement Grammy<br />

The week leading up to the 52nd<br />

annual Grammy Awards show<br />

unleashed a flurry of activity in<br />

Los Angeles at the end of January.<br />

One special gathering took place at<br />

the Wilshire Ebell Theatre the<br />

night before the formal Grammy<br />

show, as trumpeter Clark Terry<br />

was among the recipients of the<br />

Recording Academy’s 2010<br />

Lifetime Achievement Awards<br />

(that group also included blues legend<br />

David “Honeyboy” Edwards).<br />

Recording Academy President<br />

and CEO Neil Portnoy praised the<br />

honorees for their “outstanding<br />

Ulli Blobel<br />

accomplishments and passion for<br />

their craft.” He went on to add that<br />

the recipients have created a legacy<br />

“that has positively affected multiple<br />

generations.”<br />

Bandleader Gerald Wilson has<br />

known St. Louis native Terry since<br />

the two were stationed at the Great<br />

Lakes Naval Station during World<br />

War II, before Terry’s star rose in<br />

the Duke Ellington and Count<br />

Basie orchestras.<br />

“Clark should have got that<br />

award years ago,” Wilson said.<br />

“When I met him, I’d never heard<br />

such a complete trumpet player.<br />

Clark Terry and<br />

his wife, Gwen<br />

Terry, receive the<br />

Grammy from<br />

Neil Portnoy<br />

He knew all the chord progressions<br />

and the scales, could read and execute<br />

anything, and his solos were<br />

just great.”<br />

“The award was a complete<br />

surprise,” Terry said from his<br />

Leimgruber. Judging from label<br />

releases by bass clarinetist Rudi<br />

Mahall, alto saxophonist Silke<br />

Eberhard and reedist Daniel<br />

Erdmann, Berlin’s scene is<br />

stronger than ever.<br />

“I fall back on the old casts<br />

and also inspire new things,”<br />

Blobel said. “But I am also listening<br />

to what the musicians recommend<br />

to me. I don’t go into<br />

the studio with them, but all of<br />

the projects are discussed in<br />

advance. The artists are then<br />

free in their development.”<br />

Fifteen new titles on CD and<br />

DVD are already planned for the<br />

first half of 2010. While Blobel<br />

acknowledges that in the current<br />

economy the label relies on private<br />

money and public funding<br />

to survive, he remains wideeyed<br />

about the future, even<br />

gearing up to launch two more<br />

labels. Klassickwerkstatt/phil.harmonie<br />

focuses on chamber<br />

music with players from the<br />

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.<br />

Morgenland will release Jewish<br />

and Eastern European styles.<br />

He’s also writing a book that<br />

should detail his early difficulties<br />

presenting jazz behind the Iron<br />

Curtain. DB<br />

home in Pinebluff, Ark. “It makes<br />

me feel good about playing jazz all<br />

my life. Something about the St.<br />

Louis trumpet players always<br />

made you feel good about life.”<br />

—Kirk Silsbee<br />

RICK DIAMOND/COURTESY RECORDING ACADEMY<br />

April 2010 DOWNBEAT 19

�<br />

Caught<br />

Pérez Masterfully Plays,<br />

Organizes Panama Jazz Festival<br />

At some point during the seventh annual Panama Jazz Festival, it became<br />

clear that Danilo Pérez’s primary instrument was Panama itself, and he<br />

played it like a master. Invariably clad in the blue vest indicating his status<br />

as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador, Pérez—a tireless lobbyist for the<br />

cause of music as a tool for social change—seemed to be everywhere in<br />

his native Panama City during the event (which ran Jan. 11–16). He carried<br />

that message from the stage of the ornate Teatro Nacional to a meeting<br />

with the president of the Panamanian Congress to the Panama Canal,<br />

where he pressed the button that opened the gates of the Pacific-side locks<br />

at a private ceremony.<br />

Pérez shared that latter distinction with Roger Brown, president of<br />

Berklee College of Music, who announced the formation of the Berklee<br />

Global Jazz Institute (BGJI), a program headed by Pérez that teaches students<br />

with a multi-cultural scope.<br />

At a gala concert at the Teatro Nacional, the torch was passed in dramatic<br />

fashion from the BGJI faculty to its students. After opening with a<br />

spirited “Star Eyes,” an all-star quintet composed of the new program’s<br />

instructors (Pérez, Joe Lovano, John Patitucci, Terri Lyne Carrington and<br />

Jamey Haddad) followed up with Thelonious Monk’s “Rhythm-A-Ning,”<br />

only to be gradually replaced by BGJI students, who took over for the rest<br />

of the evening.<br />

For a debut on such a grand stage, the two ensembles formed by the 14<br />

young instrumentalists strode with fairly steady legs. Standouts included<br />

saxophonist Hailey Niswanger from Portland, Ore., who wielded a steely<br />

soprano on her own composition, “Balance,” and Japanese-Austrian guitarist<br />

Kenji Herbert, who exuded a relaxed confidence at the head of the<br />

first group.<br />

Though the evening was the official public kick-off for both the festival<br />

and the BGJI, both had already been underway for almost three days<br />

as a series of clinics at the Panama Canal Authority’s Centro de<br />

Capacitaciones de Ascanio Arosemena. On the first day alone, Niswanger<br />

and fellow BGJI saxophonist Jesse Scheinin had guided a dozen local<br />

reedists through a rudimentary blues, while Patitucci engaged a roomful of<br />

Wall Street Journal drama critic Terry Teachout’s words from this past<br />

summer hovered over New York’s Bleecker Street on two early January<br />

nights, as the sixth annual Winter JazzFest occupied five venues in the<br />

West Village.<br />

To stir reaction, more than one artist referred to Teachout’s mid-<br />

August assertion that young people aren’t<br />

listening to jazz. The crowds—estimated<br />

at 3,700 for the 55 acts—were predominantly<br />

young and boisterous, cheering<br />

loudly for short sets by favorites like<br />

Vijay Iyer and Darcy James Argue, and<br />

filling the clubs to capacity both nights.<br />

Indeed, the festival’s lineup seemed like<br />

an in-your-face retort to anyone who<br />

thinks that jazz doesn’t transcend generations,<br />

with fresh voices like guitarist Mary<br />

Halvorson, singer Gretchen Parlato, trumpeter<br />

Ambrose Akinmusire and bassist<br />

Linda Oh prominently featured.<br />

Playing to an elbow-to-elbow audience<br />

at Le Poisson Rouge, Argue’s 18-<br />

20 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

bass aspirants on both acoustic and electric axes, invoking a pedigree of<br />

influences from Paul Chambers to James Jamerson.<br />

Patitucci was a constant presence throughout the festival. Music from<br />

the bassist’s latest CD, Remembrance, made up the bulk of the set at the<br />

Teatro Anayansi that began as a trio with Lovano and Carrington but<br />

wound up as a quintet with Pérez and Haddad. The set closed with an exuberant<br />

run through a new Pérez piece entitled “Panama Galactico,” all the<br />

more remarkable for being penned just that afternoon.<br />

Earlier that evening, pianist Ellis Marsalis’ trio set was an amiable<br />

stroll through the New Orleans patriarch’s usual fare, drawing heavily<br />

from his recent tribute to Monk, whose influence was also felt on a sharply<br />

angular “Sweet Georgia Brown.” Son Jason brought intriguing hip-hop<br />

inflections to the table, particularly via the jittery groove he applied to<br />

Monk’s “Teo.”<br />

After an exhausting 90-minute set by Minnesota-born flamenco guitarist<br />

Jonathan Pascual that amounted to little more than a fireworks display<br />

of virtuosity both musical and physical (the hefty dancer Jose<br />

Molina), it was announced that Dee Dee Bridgewater was unable to make<br />

her scheduled appearance. The audience’s collective sigh of disappointment<br />

was soon hushed by last-minute replacement Lizz Wright’s a cappella<br />

“I Loves You, Porgy,” showcasing the dusky melancholy of her<br />

voice. Festival honoree Sonny White, Billie Holiday’s Panama-born<br />

accompanist, was honored not with his most notable composition,<br />

“Strange Fruit,” but with a warm duet of “Embraceable You” performed<br />

by Wright and Pérez. —Shaun Brady<br />

Winter JazzFest Offers Retort to Genre’s Premature Obituary<br />

Darcy James Argue’s<br />

Secret Society<br />

Danilo Pérez<br />

piece Secret Society spanned generations of big band orchestration, mixing<br />

aggressively rising brass with Sebastian Noelle’s razor-edged guitar,<br />

and backing age-old trumpet and reed solo spots with off-center ostinatos<br />

or strident backbeats. The band’s sandpaper textures and ability to raise<br />

the volume without resorting to high-note cliches place it firmly in a contemporary<br />

setting.<br />

Likewise, Iyer and his bandmates Stephan<br />

Crump and Marcus Gilmore have updated the<br />

sound of the piano trio without losing the critical<br />

balance that marked the threesomes of forerunners<br />

from Bill Evans to Keith Jarrett. Answering the<br />

expectations of the capacity audience, Iyer pulled<br />

off a live premiere of MIA’s “Galang”—the jittery,<br />

attention-grabbing highlight of his album<br />

Historicity—despite his stated concern that playing<br />

it might result in a repetitive-strain injury.<br />

Gilmore, who delivers enough of a wallop to<br />

make “Galang” sound like something off The Bad<br />

Plus’ playlist, can also churn sinuously, chopping<br />

and stirring time in imaginative ways.<br />

Several blocks north, at Zinc Bar, saxophonist<br />

JACK VARTOOGIAN/FRONTROWPHOTOS<br />

TODDI NORUM

SHIRA YUDKOFF<br />

Jaleel Shaw was carving sinuous lines, fueled by his rhythm section of<br />

bassist Ben Williams and drummer Johnathan Blake, and abetted by<br />

Aaron Goldberg on Fender Rhodes. Back on Bleecker, at the venerable<br />

Kenny’s Castaways, Halvorson’s trio was doing very different things with<br />

tempo: swirling storms of hard-strummed chaos, revving up time signatures<br />

and leaving them dangling over octave-shifted chords.<br />

Saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa—still sweating from his appearance<br />

uptown with drummer Jack DeJohnette—provided an exciting set<br />

change after Halvorson. With Dan Weiss on minimal drum kit and tablas,<br />

and Rez Abassi on guitar, the Indo-Pak Coalition created a seamless synthesis<br />

of bebop and South Asian music. The contrast between<br />

Mahanthappa’s tart alto and Abassi’s rounded tone was particularly acute,<br />

and Weiss’ adroit switches between rhythmic elements created a breathless<br />

urgency.<br />

At Sullivan Hall—the least conducive of the venues—Parlato worked<br />

the other end of the energy scale, delivering a languid set that seldom rose<br />

above an intimate whisper. — James Hale<br />

Chris Chew (left), Robert Randolph and Luther Dickinson<br />

Reunited Word Emphasizes<br />

Tumult Over Groove<br />

The Word’s take on gospel bears a closer resemblance to secular pop<br />

music than to anything devotional. Thunderous downbeats provide an<br />

underpinning for meandering guitar solos that typify a jam-band tribe<br />

gathering. The group, which debuted in 2001 with its lone self-titled<br />

album release and last toured in 2007, reunited for five dates beginning<br />

Dec. 30 at Philadelphia’s Theatre of Living Arts.<br />

The band’s lineup has remained intact. It features the North Mississippi<br />

Allstars with two high-profile guests: organ player John Medeski and<br />

pedal steel guitarist Robert Randolph.<br />

Much of the repertoire performed during the three-hour concert was<br />

similar, but never vapid. The gospel songs functioned as a starting point.<br />

Only a few featured vocals; the spotlight stayed on the pairing of<br />

Randolph and Allstars guitarist Luther Dickinson. Medeski played only a<br />

supporting role.<br />

The Word began the first set with “Stevie.” After establishing the<br />

groove, the group evoked Gov’t Mule and possibly Little Feat.<br />

“Trimmed” was lean and suggested a range of blues styles: straightforward<br />

country blues at the beginning, the barbed-wire electricity of R.L.<br />

Burnside and Junior Kimbrough by the end.<br />

From this point on the instrumentals bled into one another, making it<br />

difficult to distinguish one from the next. Some evoked Woody Guthrie,<br />

or even a hybrid of Guthrie and James Brown. The formula remained evident<br />

even during Randolph’s vocal turn on “Glory, Glory.” However, the<br />

song’s spiritual intent was lost in a hailstorm of guitars.<br />

Yet with “Wings,” which ended the second set, the band reached<br />

beyond this horizon. Dickinson’s guitar incorporated modal harmony, creating<br />

a trance-like effect as it embarked upon a prolonged crescendo. In<br />

the meantime, Randolph manned Cody Dickinson’s drum kit as Cody, in<br />

turn, donned an amplified washboard. Luther Dickinson then replaced<br />

Randolph on drums, and Cody Dickinson traded the washboard for some<br />

shakers; the brothers later pounded the drum kit in tandem. —Eric Fine

Players<br />

Danny Grissett ;<br />

Leader’s Languages<br />

Pianist Danny Grissett has called his performance<br />

of the Joe Zawinul songbook “a great<br />

study.” After playing the repertoire at New<br />

York’s Jazz Standard as part of Steve Wilson’s<br />

quintet last December, Grissett reflected on one<br />

particularly telling moment: After a bravura<br />

interpretation of “From Vienna With Love,” a<br />

classically flavored ballad, rendered with imaginative<br />

voicings and an endless stream of<br />

melody, he switched to the Fender Rhodes for<br />

“Directions,” sustaining the smoky flow with<br />

imaginative textures and strongly articulated<br />

rhythmic comp.<br />

“It was challenging to draw from all the<br />

periods of Zawinul’s life,” Grissett said. “He<br />

wasn’t playing all these styles at one time. His<br />

musical thinking changed, as did his life experiences,<br />

and the people he worked with and<br />

who were influencing him. In the bands I play<br />

with—let’s say Tom Harrell—the music is current,<br />

what Tom is writing now. Another challenge<br />

is that Joe played synth on tunes like ‘A<br />

Remark You Made,’ and the sound of the<br />

Rhodes is completely different. I’ve written<br />

some electric things, which hopefully I’ll have<br />

a chance to record. But I’ve written so many<br />

things acoustically that are more current.”<br />

Best known to the jazz public as a first-call<br />

sideman (Harrell’s steady pianist since 2005,<br />

he also performs with Jeremy Pelt, Wilson,<br />

David Weiss’ New York Jazz Composers<br />

Octet and Vanessa Rubin), Grissett presents a<br />

large slice of his acoustic repertoire on three<br />

recent Criss-Cross albums. On Promise and<br />

Encounter, he reveals himself as an emerging<br />

master of the piano trio with bassist Vicente<br />

Archer and drummer Kendrick Scott.<br />

Possessing abundant technique, he parses it<br />

judiciously throughout, triangulating strategies<br />

drawn from Mulgrew Miller, Herbie Hancock<br />

and Sonny Clark to tell cogent stories that<br />

carry his own harmonic and rhythmic signature.<br />

On Form, a late 2008 production, he augments<br />

that trio with trumpeter Ambrose<br />

Akinmusire, saxophonist Seamus Blake and<br />

trombonist Steve Davis.<br />

Each territory that Grissett navigated on the<br />

Zawinul project correlates to a component of<br />

his own personal history. Jazz is not his first<br />

language—raised in the South Central area of<br />

Los Angeles, Grissett began classical lessons at<br />

5 years old. He remained on that track through<br />

high school and into college at California State<br />

University, Dominguez Hills. Flutist James<br />

Newton put him in touch with Los Angeles<br />

pianist Kei Akagi, who gave Grissett a handful<br />

of lessons, which he piggybacked into intense<br />

22 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

analysis of iconic recordings by his sonic mentors.<br />

As he completed the first year of a twoyear<br />

masters program at Cal Arts, he attended<br />

the Thelonious Monk Institute (1999–2001),<br />

commuting an hour every day to fulfill both<br />

obligations. Meanwhile, Grissett was assimilating<br />

real-world information on freelance jobs<br />

with such California hardcore jazz mentors as<br />

drummer Billy Higgins, tenor saxophonist<br />

Ralph Moore and trombonist Phil Ranelin. He<br />

also had a long-term weekend gig with bassist<br />

John Heard and drummer Roy McCurdy.<br />

“I was working at least five times a week<br />

pretty steadily,” Grissett said. “Hip-hop and<br />

r&b gigs with Rhodes and synth, and a lot of<br />

solo piano at private parties. About nine<br />

months into the gig with John and Roy, they<br />

told me, ‘You’ve got to get out of here and go<br />

to New York.’ I knew I’d grow a lot faster and<br />

have more opportunities to play original music.<br />

I saved a nice chunk of money that would last<br />

me four five months—it was always in mind<br />

that if things got really hard, I could return.”<br />

Within weeks of his 2003 arrival, Grissett<br />

was working steadily with Vincent Herring,<br />

with whom he recorded twice. By early 2004<br />

he was Nicholas Payton’s keyboardist.<br />

“I grew through seeing how flexible his<br />

approach was, like a fresh start every night,”<br />

Grissett said. “It made me learn the level of<br />

concentration it takes to play this music at a<br />

consistently high level.”<br />

Grissett continues to flourish in Harrell’s<br />

more structured environment.<br />

“Tom doesn’t dictate how we’re going to<br />

play, but he writes piano parts, so he usually<br />

has something he wants to hear—or some starting<br />

point to build on,” Grissett said. “The content<br />

is so strong that the notes on the page<br />

guide the music; the harmony forces me to play<br />

different melodic contours in approaching my<br />

own music and standards.”<br />

Ensconced in Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill section<br />

and a recent father, Grissett anticipates remaining<br />

an East Coaster. “Artistically speaking, I feel<br />

comfortable,” he said. “I always feel like I’m a<br />

bit behind my peers, but less so now. I want to<br />

pool my resources and make something happen<br />

as a leader. It’s about time, already.”<br />

—Ted Panken<br />

JACK VARTOOGIAN/FRONTROWPHOTOS

Dana Hall ;<br />

Illuminating<br />

Space<br />

When Dana Hall talks about global<br />

connections or musical nuances,<br />

his words convey a quiet authority.<br />

The drummer’s background—<br />

which embraced equally intense<br />

levels of science and technology<br />

alongside music and scholarship—<br />

has provided him with a unique<br />

perspective on those large and<br />

small concepts. And Hall’s recent<br />

CD debut as a quintet leader, Into<br />

The Light (Origin), shows how he<br />

blends those disparate ideas.<br />

Today, Hall is mainly known<br />

for directing the Chicago Jazz<br />

Ensemble, playing prominent<br />

sideman gigs and teaching at the<br />

University of Illinois at Urbana-<br />

Champaign. But when he first<br />

arrived in the Midwest from<br />

Philadelphia in the late ’80s, it<br />

was to study aerospace engineering<br />

and percussion at Iowa State<br />

University. Hall went on to help<br />

design propulsion systems and aircraft<br />

for Boeing, later to give up<br />

this potentially lucrative career for<br />

a riskier life in jazz, but he stresses<br />

the internal affinities.<br />

“A certain interest in the minutia<br />

comes from studying engineering, which is<br />

helpful when you’re performing music,” Hall<br />

said. “Because you’re thinking peripherally—in<br />

a circular fashion, rather than just what you’re<br />

playing or another soloist is playing. And I’m<br />

interested in creating formulas to come up with<br />

something new and interesting, whether it’s a<br />

flight mechanics problem or a new harmonic<br />

progression.”<br />

Hall kept that mindset when he left Seattlebased<br />

Boeing for New York in 1991 to complete<br />

his music degree at William Paterson<br />

University. But he also knew that skills, rather<br />

than theories, would open doors on the jazz<br />

scene. His abilities became clear as he worked<br />

with prominent leaders representing a range of<br />

generations: from Betty Carter and Ray Charles<br />

to Roy Hargrove and Joshua Redman. Although<br />

he found these experiences invaluable, Hall felt<br />

that a move to Chicago in 1994 would be key to<br />

developing his own personality.<br />

“In New York, I could walk down a path and<br />

not know where I wanted to go,” Hall said. “Be<br />

a swinger or on the downtown scene? Down this<br />

particular path and play like Milford Graves? Or<br />

play like Billy Higgins? Or play like Dana Hall?<br />

Moving to Chicago afforded me the opportunity<br />

to have that growth.”<br />

Chicago’s musical community sped up the<br />

evolution.<br />

JACOB HAND<br />

“The first time Von Freeman counted off a<br />

fast tempo, no one ever asked me to play that<br />

fast before,” Hall said. “But I knew he had my<br />

back and there was this love, and I never had<br />

that in New York.”<br />

Numerous opportunities followed—musical<br />

and educational. Hall is currently working on his<br />

Ph.D. in ethnomusicology at the University of<br />

Chicago, where his dissertation is on<br />

Philadelphia soul music of the ’70s.<br />

“The entire idea of diaspora is central to my<br />

thinking about my own music and my own work<br />

as a scholar,” Hall said. “It’s exciting that there’s<br />

a connection to the music you hear in Senegal to<br />

the music that you’d hear in Panama, New York,<br />

Chicago or Philadelphia. There are rhythmic and<br />

harmonic elements that fuse them together. The<br />

more I look at the late Teddy Pendergrass or<br />

Otis Redding, I get a sense that it’s connected to<br />

John Coltrane or Fela Kuti.”<br />

In particular, Hall points to combinations of<br />

complexity and simplicity throughout African<br />

music and in Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes.<br />

He’s after the same ideals on his compositions,<br />

like “The Path To Love” from Into The Light.<br />

“There’s a singability on the surface, but<br />

below the surface there’s something going on<br />

that has more depth. This sweet and sour, salt<br />

and pepper, yin and yang is something I’m trying<br />

to illuminate.” —Aaron Cohen<br />

April 2010 DOWNBEAT 23

SUBSCRIBE!<br />

1-877-904-JAZZ<br />

24 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

Players<br />

Luis Bonilla ;<br />

Angst-Free<br />

Brass<br />

Luis Bonilla, who boasts a broad<br />

range of credits with established<br />

bands, has turned his attention to<br />

becoming a bandleader in his<br />

own right. The trombonist has<br />

assembled a group of his peers<br />

for the recent album I Talking<br />

Now (Planet Arts), and he has<br />

already booked studio time for a<br />

sequel.<br />

“It’s complete commitment<br />

to my own groups from this<br />

point on,” Bonilla said. “I was<br />

extremely busy freelancing and<br />

playing with a lot of different<br />

people, and I just can’t spread<br />

myself so thin now.”<br />

I Talking Now (Planet Arts)<br />

features Bonilla’s working quintet<br />

of pianist Arturo O’Farrill,<br />

drummer John Riley, bassist<br />

Andy McKee and tenor saxophonist<br />

Ivan Renta. The album grew out of associations<br />

with musicians in the Vanguard Jazz<br />

Orchestra, O’Farrill’s Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra<br />

and various Charles Mingus tribute bands.<br />

Bonilla’s career encompasses Latin music and<br />

free-jazz, but the new release focuses mostly on<br />

hard-bop while showcasing the leader’s big,<br />

brassy tone and store of ideas as a soloist.<br />

“For the way I like to present music, the<br />

intent is to be as accessible as it is challenging to<br />

not only the musicians themselves, but [also for]<br />

the listener,” Bonilla said. “It’s really unapologetic—just<br />

constant risk-taking. Just five confident<br />

voices with the sole intent of really playing<br />

together and really trying to get a big band<br />

sound from a small group setting.”<br />

Bonilla freely admits to eclectic tastes<br />

extending well beyond jazz, not to mention his<br />

chosen instrument. He refers to Led Zeppelin as<br />

his favorite band, and also expresses a penchant<br />

for everything from Brazilian music to<br />

American funk bands.<br />

“It’s not that I’m speaking different languages—it’s<br />

the same language, just different<br />

dialects,” he said. “If we limit ourselves to one<br />

kind of music, then we may be shortchanging<br />

ourselves. I always was taught and encouraged<br />

to create my own scene and create my own<br />

voice. The fact that I’m so versatile makes it<br />

even better because I carry a little bit of each of<br />

those influences, whether they’re rock, funk,<br />

jazz, soul, salsa or Brazilian.”<br />

Saxophonist Donny McCaslin admires<br />

Bonilla’s technique, especially how he applies it.<br />

“He’s a very natural player; you never feel<br />

him laboring on the instrument,” said McCaslin,<br />

who has known Bonilla since high school. “He’s<br />

got so much talent that there are many things<br />

that are going to be possible for him.”<br />

Bonilla attended California State University,<br />

Los Angeles, and gained experience in salsa<br />

bands and big bands (including Gerald Wilson<br />

and Pancho Sanchez) during the latter half of the<br />

’80s. He moved to New York in 1991, where he<br />

earned a graduate degree at Manhattan School of<br />

Music. He attracted attention while performing<br />

with Lester Bowie’s Brass Fantasy, and by the<br />

late 1990s had become a first-call sideman with<br />

the likes of McCoy Tyner, Willie Colón, Astrud<br />

Gilberto, Toshiko Akiyoshi and Dave Douglas.<br />

Bonilla teaches at Temple University,<br />

Manhattan School of Music and Queens<br />

College. His first two albums, Pasos Gigantes<br />

(1998) and ¡Escucha! (2000), focus on more<br />

traditional Latin jazz repertoire. In 2007 he<br />

released Terminal Clarity (2007), a live<br />

recording that combines Latin music with freejazz.<br />

The group, Trombonilla, has performed<br />

sporadically since the late 1990s with a host of<br />

musicians.<br />

Bonilla’s quintet, I Talking Now, features a<br />

set lineup, a first for Bonilla.<br />

“The true benefit of using musicians who are<br />

this experienced and who are my peers is they<br />

understand my music and they understand my<br />

intent,” Bonilla said. “It puts me at ease, which<br />

greatly benefits the music because I’m no longer<br />

distracted by unnecessary drama.” —Eric Fine<br />

SURESH SINGARATHAM

Steve Colson ; Self-Sufficient Gifts<br />

Even though pianist Steve Colson has yet to<br />

become a household name after more than 30<br />

years in jazz, the title of his latest disc, The<br />

Untarnished Dream (Silver Sphinx), speaks<br />

volumes. The name comes from one of the<br />

song’s lyrics about life itself as a gift.<br />

“A lot of time we can get too wrapped up in<br />

the commercial aspect of music and life,”<br />

Colson said. “We don’t really stop and appreciate<br />

life and being able to share with others.”<br />

Colson has been sharing his musical gifts<br />

with a wide cast of musicians, thanks, in part,<br />

to his long involvement with the Association<br />

for the Advancement of Creative Musicians<br />

(AACM). For his new disc, Colson called<br />

bassist Reggie Workman and Andrew Cyrille<br />

to play along with his singing wife, Iqua<br />

Colson. Casting a balance between post-modern<br />

bebop and free-jazz, Colson recasts songs<br />

that were originally composed for larger<br />

ensembles. He says that when he writes, he<br />

often hears elaborate harmonies and contrapuntal<br />

melodies that call for different voices. “In<br />

terms of thinking of the content, I try to get the<br />

most bang for the buck,” he said.<br />

The AACM also taught Colson self-sufficiency,<br />

a quality that comes through nearly<br />

every aspect of The Untarnished Dream, from<br />

the disc artwork that the pianist created to his<br />

ownership of the label (along with his wife).<br />

“The AACM taught us that you have to pursue<br />

your own vision even if you have to fight<br />

an uphill battle,” Colson said.<br />

Colson was familiar with uphill battles,<br />

though, before joining the AACM in 1972.<br />

When he arrived in Chicago from East Orange,<br />

N.J., in 1967, he attended Northwestern<br />

University to study classical piano during a<br />

time when the institution was deciding to allow<br />

more black students on its campus. The school<br />

didn’t have a program for jazz when he arrived.<br />

“You couldn’t practice jazz at Northwestern,”<br />

Colson laughed. “If someone heard me<br />

playing jazz in the practice room, they would<br />

bang on the door.”<br />

Still, he met some kindred spirits, most<br />

notably Chico Freeman, with whom he formed<br />

a jazz band that played at various local events.<br />

It was with Freeman in 1968 that he first discovered<br />

the AACM through a poster advertising<br />

a Fred Anderson concert.<br />

Colson and Freeman explored more AACM<br />

concerts and eventually joined. At the same<br />

time, Northwestern started a jazz program.<br />

Colson remembers trying out: the director<br />

asked him to play a song and improvise but it<br />

couldn’t be a blues. Colson played Bobby<br />

Timmons’ “Dat Dare” and was disqualified<br />

because the teacher said to not play the blues.<br />

“But it wasn’t a blues tune—it’s bluesy,”<br />

Colson said. “This guy didn’t know the difference<br />

between a blues and a popular song structure.<br />

One of the guys who did get in the band<br />

would call me and ask how to play the piano<br />

changes on the charts that they had.”<br />

Which is something else he can laugh about<br />

now. —John Murph<br />

SHARON SULLIVAN RUBIN

christian<br />

SCOTT<br />

SHOWS HIS TEETH<br />

By Jennifer Odell // Photo by Jimmy Katz<br />

During Jazz Fest in New Orleans, trumpeter Christian Scott<br />

was driving home after playing a late-night gig with Soulive<br />

when he noticed a car trailing him by the Claiborne Street<br />

underpass. At first he was afraid he was going to be the<br />

target of a robbery. When the sirens came on, he realized<br />

he was being pulled over.<br />

In the moments that followed, he says, nine police officers<br />

drew their guns on him, and he was dragged from the car<br />

and thrown on the hood. Not wanting to become the next<br />

Amadou Diallo, he suggested the officer get his ID out of his<br />

wallet while he kept his hands in the air.<br />

“ Oh, we got one of these type of niggers,” quipped a cop.<br />

In the course of reacting to the use of that word, the slight,<br />

25-year-old musician was told to shut up unless he wanted<br />

his mother to pick him up “ from the morgue.”<br />

Log on to concordmusicgroup.com/cscottjazz to hear<br />

full streaming audio of “The Eraser” from Christian<br />

Scott’s CD Yesterday You Said Tomorrow.

Two years later, Scott is fighting back—and<br />

he’s using music to do it.<br />

“It stands for Ku Klux Police Department,”<br />

he said, explaining “K.K.P.D.,” the title of the<br />

first track on his new album, Yesterday You Said<br />

Tomorrow.<br />

The disc is Scott’s third album for Concord<br />

and maybe the first one on which he lives up to<br />

that ineffable “potential” his critics have pined<br />

for since his 2005 debut, Rewind That. That<br />

album polarized audiences, earning him a<br />

Grammy nomination on the one hand, and on<br />

the other, reviews like the New York Times’<br />

accusation that his “toothless fusion … never<br />

coalesces into a worthy showcase for his considerable<br />

talent.”<br />

Five years later, Scott’s music is anything<br />

but toothless—a point affirmed last summer<br />

when he won the Rising Star–Trumpet category<br />

of DownBeat’s International Critics Poll,<br />

well before Yesterday You Said Tomorrow<br />

was released.<br />

“K.K.P.D.” is somewhat of a benchmark for<br />

what he’s done with the entire album, which is<br />

to use music the way Keith Haring used graffiti—as<br />

a soapbox.<br />

He puts it a different way, of course.<br />

“The impetus behind the [album] was to illuminate<br />

the fact that the same dilemmas that<br />

dominated the social and musical landscape of<br />

the ’60s have not been eradicated, only refined,”<br />

28 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

he said from a London hotel room in November,<br />

summarizing a statement he was writing about<br />

the album for his team at Concord.<br />

“The record seeks to change this dynamic by<br />

re-engaging these newly refined, pre-existing<br />

problems in our social structure in the same<br />

ways that our predecessors did.”<br />

With an opening track about racial profiling<br />

and discrimination, a mid-point tune about<br />

Proposition 8 and a closing aria about the legacy<br />

of Roe vs. Wade, Scott, 27, meets the challenge<br />

he set for himself and then some.<br />

His meticulously executed musical choices<br />

give the whole album an almost operatic quality,<br />

as dramatic tension unfolds between guitar and<br />

drums or piano and bass, while Scott’s unnervingly<br />

controlled trumpet sounds an alarm that<br />

either polarizes or lulls the other parts into a<br />

comforting common ground.<br />

In retelling the story of his near-arrest in<br />

New Orleans, Scott says he constructed personas<br />

for each of the parts on “K.K.P.D.” Matt<br />

Stevens’ guitar alludes to a strain of country<br />

music popular decades ago in Tennessee,<br />

where the Klan was founded. In the song’s<br />

intro, a country-tinged melody brushes up<br />

somewhat disruptively against Jamire<br />

Williams’ West African drum rhythms before<br />

the lull of Scott’s horn trains your ears to disregard<br />

the earlier musical conflict.<br />

This is all delivered with the hauntingly<br />

deep tone that initially caught critics’ attention<br />

back in 2005.<br />

“I wanted to create a palette that referenced<br />

the ’60s’ depth and conviction and context and<br />

subject matter and sound,” he said. “But in a<br />

way that illuminated the fact that my generation<br />

of musicians have had the opportunity to<br />

study the contributions of our predecessors,<br />

thus making our decision-making process<br />

musically different.<br />

“That dynamic was then coupled with superimposition<br />

of textures from our era, so that textures<br />

from my generation were sort of married<br />

with the ones from the past.<br />

“And then the last part, which is probably of<br />

paramount importance, was that I wanted it to be<br />

recorded as if it was in the ’60s.”<br />

As Scott reads from the beginnings of a<br />

prepared statement over the phone, a<br />

quote from an interview that took place<br />

some 18 months earlier—when he’d been shooting<br />

equally high as far as the ambition of his<br />

thoughts about the new music—comes to mind.<br />

“If I can get this [album] to be what I want it to<br />

be,” he’d said, “I feel like it can change the<br />

scope of everything that’s happening.”<br />

Whether the album will affect the direction<br />

of new music in general remains to be seen. But<br />

what stood out back in 2008 as he chatted informally<br />

at a Thai restaurant near his Brooklyn

apartment is even more apparent now. Scott’s<br />

appreciation for the ability of music to tell stories<br />

and to make social commentary is rare, and<br />

the way in which he follows through on those<br />

ideas is unique.<br />

Scott’s company, like his music, has a comfortable<br />

intensity to it—an easy warmth that<br />

wins you over even when he’s on a mission to<br />

change your mind about something.<br />

Though gracious and polite, Scott presents<br />

his point of view with the same confident<br />

authority he puts into his live shows. And even<br />

when what he says rubs folks the wrong way,<br />

30 DOWNBEAT April 2010<br />

his honest expression comes with a grain of<br />

erudite salt.<br />

Take his position that the neo-classicist<br />

movement has such an overbearing presence in<br />

jazz education and contemporary music that<br />

young players are discouraged from trying to<br />

move past it. Yes, that means he thinks it’s time<br />

to find a new, post-Wynton Marsalis era.<br />

But his new album is at its core a contemporary<br />

riff on bebop and post-bop. And so was<br />

Marsalis’ self-titled 1981 release.<br />

“He’s very diligent in trying to learn and do<br />

new things,” said McCoy Tyner, who featured<br />

Scott as a special guest on the road in 2008.<br />

“He’s considerate of the tradition of the music<br />

and what happened before and moving ahead to<br />

what’s happening in the future.”<br />

Tyner’s right. The second track on Yesterday<br />

You Said Tomorrow is a cover of Radiohead’s<br />

“The Eraser,” but its washed production—courtesy<br />

of Rudy van Gelder—gives it a sepia-toned<br />

sound that matches the gritty quality of the otherwise<br />

all-original album.<br />

“I know he’s made some comments about<br />

certain things,” Tyner says. “He’s opinionated,<br />

but he has a right to have his own opinion. I give<br />

him credit for that. It’s reflected in his playing.”<br />

Tyner and Scott met in 2006, when the<br />

young trumpeter was tapped for Tyner’s The<br />

Story Of Impulse. Tyner heard something in<br />

Scott’s sound that reminded him of “what cats<br />