the pleasure of showing & looking at words - Belle Lettere

the pleasure of showing & looking at words - Belle Lettere

the pleasure of showing & looking at words - Belle Lettere

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

THE PLEASURE OF SHOWING & LOOKING<br />

AT WORDS<br />

by Manfredo Massironi<br />

THE ENTRY<br />

Calligraphy has always had complic<strong>at</strong>ed and transversal rel<strong>at</strong>ionshÔs<br />

w⁄h many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> events, proceßes, discoveries, techniques and arts<br />

with which it has been required to live, or <strong>at</strong> least interaÀ. `ese rel<strong>at</strong>ionshÔs,<br />

which are always slightly out <strong>of</strong> phase, regard:<br />

1. rel<strong>at</strong>ionships with <strong>the</strong> text – writing and reading – and <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

with <strong>the</strong> press, <strong>of</strong>ten dialectical and occasionally even conflictual.<br />

2. bonds <strong>of</strong> kinship with <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> art, and <strong>the</strong>refore frequent rel<strong>at</strong>ionships<br />

<strong>of</strong> contiguity with o<strong>the</strong>r means <strong>of</strong> expression, communic<strong>at</strong>ion,<br />

and aes<strong>the</strong>tic research.<br />

3. different rel<strong>at</strong>ionships <strong>of</strong> funÀional⁄y in di°erent cultures.<br />

Due to <strong>the</strong> vast dimensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subject and <strong>the</strong> limits to my knowledge,<br />

a system<strong>at</strong>ic consider<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> complic<strong>at</strong>ed questions summarized<br />

in <strong>the</strong> three points above will not be possible. The prepar<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> cards dealing ra<strong>the</strong>r casually with a number <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

aspects must neceÊarily represent something <strong>of</strong> a short-cut for me,<br />

in which I hope to draw <strong>at</strong>tention to <strong>the</strong> elements <strong>of</strong> gre<strong>at</strong>est curiosity<br />

and interest in an <strong>at</strong>tempt to cultiv<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> certain “lightness” th<strong>at</strong><br />

Calvino aÇrms as being <strong>the</strong> prerog<strong>at</strong>ive <strong>of</strong> good liter<strong>at</strong>ure, and which<br />

I believe to be one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> essential elements and <strong>pleasure</strong>s <strong>of</strong> calligraphy<br />

as well.<br />

THE ORIGINS, BUT NOT THE BEGINNING<br />

The first singularity <strong>of</strong> calligraphy regards its <strong>of</strong>ficial birth during a<br />

period <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Renaißance. We can all easily imagine th<strong>at</strong> calligraphy<br />

was already alive and flourishing <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> time, with <strong>the</strong> awareness provided<br />

by <strong>the</strong>ir discoveries and inventions and <strong>the</strong> reassurance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

geometry and <strong>the</strong> truths <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir proportions th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Italian artists<br />

and humaniÌs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Renaissance decreed its cre<strong>at</strong>ion. Most probably,<br />

in <strong>the</strong> approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 4500 years between <strong>the</strong> first appearance <strong>of</strong> writ-<br />

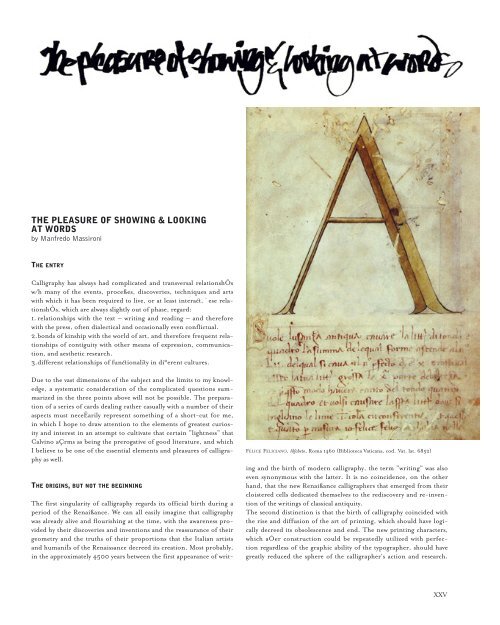

FELICE FELICIANO, Alfabeto, Roma 1460 (Biblioteca V<strong>at</strong>icana, cod. V<strong>at</strong>. l<strong>at</strong>. 6852)<br />

ing and <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> modern calligraphy, <strong>the</strong> term “writing” was also<br />

even synonymous with <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>ter. It is no coincidence, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

hand, th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> new Renaißance calligraphers th<strong>at</strong> emerged from <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

cloistered cells dedic<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>the</strong>mselves to <strong>the</strong> rediscovery and re-invention<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> writings <strong>of</strong> classical antiquity.<br />

The second distinction is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> calligraphy coincided with<br />

<strong>the</strong> rise and diffusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> printing, which should have logically<br />

decreed its obsolescence and end. The new printing characters,<br />

which aÓer construction could be repe<strong>at</strong>edly utilized with perfection<br />

regardless <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> graphic ability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> typographer, should have<br />

gre<strong>at</strong>ly reduced <strong>the</strong> sphere <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> calligrapher's action and research.<br />

XXV

Precisely <strong>the</strong> opposite occurred, however. European calligraphers,<br />

first <strong>of</strong> whom <strong>the</strong> Italians, provided <strong>the</strong> German printers who had<br />

come to Italy with newer, elegant and better proportioned characters<br />

than <strong>the</strong> crudely formed approxim<strong>at</strong>ive letters <strong>the</strong>y were accustomed<br />

to using.<br />

GEOFROY TORY, Champ fleury, Lettres <strong>at</strong>tiques, 1529<br />

We owe <strong>the</strong> oldest work to reach modern times – in which <strong>the</strong> geometrical<br />

struÀure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> letters is performed on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

square and circle – to <strong>the</strong> Veronese Humanist Felice Feliciano, who<br />

derived his charaÀers first published in 1463 from his studies <strong>of</strong><br />

Roman inscriptions.<br />

Thanks to ano<strong>the</strong>r farsighted mechanism <strong>of</strong> hiÌory – those th<strong>at</strong><br />

make things proceed differently than <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong> myopia <strong>of</strong> human<br />

logic might o<strong>the</strong>rwise indic<strong>at</strong>e – <strong>the</strong> invention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> printing press<br />

promoted, ra<strong>the</strong>r than discouraged, <strong>the</strong> production and popularity<br />

<strong>of</strong> manuals <strong>of</strong> calligraphy. By expanding <strong>the</strong> supply <strong>of</strong> liter<strong>at</strong>ure, <strong>the</strong><br />

printing press also increased <strong>the</strong> demand for access to writing.<br />

Writing was a tool for <strong>the</strong> HumaniÌs, whose beauty, utility and decor<br />

was based on proportions, or <strong>the</strong> hidden rel<strong>at</strong>ionships <strong>of</strong> arithmetic-geometric<br />

n<strong>at</strong>ure destined to reveal <strong>the</strong> perfeÀion and harmony<br />

th<strong>at</strong> governs <strong>the</strong> universe, from <strong>the</strong> celestial spheres to <strong>the</strong> humble<br />

letters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> alphabet. Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> leading artists and scientists <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Renaissance, such as L.B. Alberti, L. Pacioli, and A. Dürer,<br />

dedic<strong>at</strong>ed serious effort to character design and architeÀure. The true<br />

master calligraphers, such as Ludovico Arrighi (known as Vicentino),<br />

who perfected and gave final form to <strong>the</strong> Chancellery script and<br />

Sigismondo Fante da Ferrara, <strong>the</strong> author <strong>of</strong> an important tre<strong>at</strong>ise on<br />

<strong>the</strong> shapes and proportions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> principal scripts published in 1514,<br />

developed <strong>the</strong> basic texts on <strong>the</strong> geometrical rules governing character<br />

design th<strong>at</strong> came to constitute a point <strong>of</strong> reference for all <strong>the</strong> calligraphers<br />

in Europe.<br />

The numbers and <strong>the</strong> geometrical correspondence th<strong>at</strong> confirm<br />

<strong>the</strong> choices, however, were first identified and manipul<strong>at</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong><br />

Renaissance designers on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> esoteric, mythological, and<br />

astrological justific<strong>at</strong>ions.<br />

Choices made on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> magic and mystery remain in place only<br />

as long as <strong>the</strong>y continue to be supported by faith, while explan<strong>at</strong>ions<br />

dict<strong>at</strong>ed by faith can permit <strong>the</strong>mselves <strong>the</strong> luxury <strong>of</strong> being r<strong>at</strong>ionally<br />

inconsiÌent.<br />

XXVI<br />

`is aı⁄ude – which toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> demonstr<strong>at</strong>ion provided by<br />

Fante's book, <strong>the</strong> `eorica et pr<strong>at</strong>ica, set <strong>the</strong> standard for <strong>the</strong> European<br />

calligraphers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> day – can be sÕn in <strong>the</strong> amusing di<strong>at</strong>ribe provided<br />

by <strong>the</strong> French calligrapher Ge<strong>of</strong>roy Tory in his handsome book<br />

entitled Champ Fleury raised in regard to L. Pacioli, S. Fante, and L.<br />

Vicentino. Tory's work deals with «The Art and science<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> appropri<strong>at</strong>e shape and proportion <strong>of</strong> Attic<br />

letters, also known as Ancient letters or even Roman<br />

letters in common speech». Tory claims th<strong>at</strong> Bro<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Luca Pacioli had designed Attic letters without saying<br />

anything or providing explan<strong>at</strong>ions on his method,<br />

and this was no marvel, Tory continues, upon hearing<br />

th<strong>at</strong> Pacioli had taken his letters from old Leonardo<br />

da Vinci, who had recently expired in Amboise.<br />

This explains why <strong>the</strong> characters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monk were not<br />

drawn in <strong>the</strong> correct proportions th<strong>at</strong> Tory himself<br />

would provide as examples in his book.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> same way, nei<strong>the</strong>r had <strong>the</strong> classic letters <strong>of</strong><br />

Sigismondo Fante or Ludovico Vicentino been<br />

drafted correctly in Tory's view. He also st<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong><br />

although he was unaware if Dürer had provided his<br />

own <strong>the</strong>ories in regard, <strong>the</strong>y could not have been<br />

anything but fallacious, given th<strong>at</strong> it was clear th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

German artist had made miÌakes in <strong>the</strong> proportions<br />

<strong>of</strong> numerous letters presented in his book on perspective.<br />

Tory resumes <strong>the</strong> subject fur<strong>the</strong>r, complete<br />

with his technical commentary. After first explaining how <strong>the</strong> leıer<br />

“A” must be drawn, and juÌiÃing his choice with<br />

…as I have already said, th<strong>at</strong> A, if it be made according to art, must have ⁄s right leg as<br />

thick as <strong>the</strong> tenth part <strong>of</strong> its height, which is <strong>the</strong> breadth <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ten units contained<br />

between <strong>the</strong> eleven equidistant lines drawn in its square, and not as thick as <strong>the</strong> ninth part<br />

LUCA PACIOLI, Divina proportione, Venezia 1509

<strong>of</strong> its height, as Frere Lucas Paciolus <strong>of</strong> Bourg SainÀ-Sepulchre says in <strong>the</strong> Divina proportione<br />

which he says th<strong>at</strong> he wrote. His own <strong>words</strong> in vulgar Italian are as follows:<br />

Questa letera A si cava del tondo, e del suo quadro. La gamba da man<br />

drita vol esser grossa de la nove parti luna de lalteza. Th<strong>at</strong> is to say: “This<br />

letter A is partly rounded and partly square. The right leg must be as thick as one <strong>of</strong> nine<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> its height.” He divides his square into only nine parts & gives no reason <strong>the</strong>refor;<br />

wherefore, under correction, it seems to me th<strong>at</strong> he speaks ignorantly, going astray with <strong>the</strong><br />

very first letter, & so with all <strong>the</strong> rest. I have been told th<strong>at</strong> all th<strong>at</strong> he did in this m<strong>at</strong>ter he<br />

took secretly from <strong>the</strong> l<strong>at</strong>e Messire Leonardo da Vinci, who was a gre<strong>at</strong> ma<strong>the</strong>m<strong>at</strong>ician,<br />

painter, and image-maker. Sigismund Fante, a nobleman <strong>of</strong> Ferrara, who, as I have said,<br />

strives to teach how to make divers sorts <strong>of</strong> letters, gives no reasons for <strong>the</strong> proportions <strong>of</strong> his<br />

said letters, especially for <strong>the</strong> Antique letter. He, too, has gone astray in <strong>the</strong> A, <strong>the</strong> E, <strong>the</strong> L,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Q, <strong>the</strong> S, <strong>the</strong> T, and <strong>the</strong> X, which are not made as <strong>the</strong>y should be, ei<strong>the</strong>r in dimensions<br />

or in shape. The keen eye <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> learned & studious man will be able easily to perceive this<br />

in <strong>the</strong> book which <strong>the</strong> said Sigismund has printed, entitled `eorica et pr<strong>at</strong>ica.<br />

But wh<strong>at</strong> are <strong>the</strong> elements Tory uses to base his certainties? We find an<br />

example <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> his third book, which explains how punctu<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

marks are drawn:<br />

I here describe & draw <strong>the</strong>se three kinds <strong>of</strong> points only, according to <strong>the</strong> fashion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ancients, and according as <strong>the</strong> Attic letter demands, knowing full well th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> writers on<br />

grammar in <strong>the</strong> L<strong>at</strong>in tongue tre<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> several o<strong>the</strong>r points, <strong>of</strong> which Aulus Antonius Orobius<br />

mentions eleven di°erent kinds, which are Punctum suspensivum, Geminum<br />

punctum, Semipunctum, Hypopliroma, Comma, Colon, Periodus,<br />

Interrog<strong>at</strong>ivum, Responsivum, Admir<strong>at</strong>ivum, & Paren<strong>the</strong>sis. Th<strong>at</strong><br />

is to say, <strong>the</strong> suspensive point, <strong>the</strong> double point, <strong>the</strong> half-point, <strong>the</strong><br />

hooked point, <strong>the</strong> incisive point, <strong>the</strong> bre<strong>at</strong>hing point, <strong>the</strong> concluding<br />

point, <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong> interrog<strong>at</strong>ion, <strong>the</strong> responsive point, <strong>the</strong> point <strong>of</strong><br />

admir<strong>at</strong>ion, and <strong>the</strong> interposing point. All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se, to <strong>the</strong> number<br />

<strong>of</strong> eleven, secretly & in divine fashion confirm me th<strong>at</strong> I have justifiably<br />

divided my square within which to make <strong>the</strong> Attic leıers, into<br />

eleven points, which is a manifest token th<strong>at</strong> I have not gone astray,<br />

but have studiously and surely discovered <strong>the</strong> secret <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> even & odd<br />

numbers, th<strong>at</strong> is to say, <strong>of</strong> eleven points containing between <strong>the</strong>m ten<br />

uniform units, required according to <strong>the</strong> divine, and yet heret<strong>of</strong>ore<br />

almost unknown, opinion <strong>of</strong> excellent ancients.<br />

The days in which bitter polemics were waged on whe<strong>the</strong>r letters were<br />

to be divided in 9 parts or 11 have decidedly passed. The certainties<br />

th<strong>at</strong> one is prepared to advoc<strong>at</strong>e <strong>at</strong> all costs have decreased, and not<br />

only in regard to <strong>the</strong> geometrical grids in which <strong>the</strong> letters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

alphabet were designed. There is no regret in this observ<strong>at</strong>ion and<br />

no nostalgia for aßurances lost, even if <strong>the</strong> odd minute certainty here<br />

and <strong>the</strong>re provides a support th<strong>at</strong> might help us to stay on our feet.<br />

We must learn to accustom ourselves to <strong>the</strong> support provided by only<br />

<strong>the</strong> smaller certainties and distrust <strong>the</strong> larger, however.<br />

The works on display in Cittadella and collected in this volume provide<br />

evident testimony <strong>of</strong> this st<strong>at</strong>e <strong>of</strong> affairs. Alongside <strong>the</strong> works<br />

inspired by <strong>the</strong> shapes and content <strong>of</strong> classical calligraphy, re-proposing<br />

<strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong>ir personalized versions with all <strong>the</strong> <strong>pleasure</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

rediscovering and reviving <strong>the</strong>ir internal harmony, <strong>the</strong>re are o<strong>the</strong>rs in<br />

which <strong>the</strong> leıers and script demonstr<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> search for o<strong>the</strong>r m<strong>at</strong>erials<br />

where pen and ink are not used, and <strong>the</strong> quest for new m<strong>at</strong>erials to<br />

replace <strong>the</strong> sheaf <strong>of</strong> paper; <strong>the</strong>re are works in which <strong>the</strong> text reluctantly<br />

concedes itself to reading. Everyone is aware th<strong>at</strong> aes<strong>the</strong>tic research<br />

must necessarily pass through <strong>the</strong> valley <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> shadow <strong>of</strong> doubt, and<br />

thus here in C⁄tadella we may witness calligraphy as it plays <strong>at</strong> hideand-seek<br />

with <strong>the</strong> text, on one hand, and with painting or instal-<br />

BARTOLOMEO SANVITO, PADOVA 1495<br />

l<strong>at</strong>ions on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. In <strong>the</strong>se cases, <strong>the</strong> letters and <strong>the</strong> <strong>words</strong> claim<br />

priority by aßuming <strong>the</strong> space <strong>of</strong> an unexpected monument (Paolo<br />

Marcolongo), or dissolve to become phantasms which openly declare<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves incapable <strong>of</strong> bearing <strong>the</strong> weight <strong>of</strong> any specific reference.<br />

CALLIGRAPHY AND CALLIGRAPHIES<br />

If <strong>the</strong> entirely Western prejudice th<strong>at</strong> denigr<strong>at</strong>es calligraphy to <strong>the</strong> role<br />

<strong>of</strong> a minor art could ever be overcome and a comprehensive study on<br />

<strong>the</strong> world history performed, <strong>the</strong> starting point would invariably<br />

be <strong>the</strong> three gre<strong>at</strong> civiliz<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> writing: <strong>the</strong> Chinese, whose ideographic<br />

scripture goes far beyond <strong>the</strong> realm <strong>of</strong> spoken language, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Arabic and Western, with <strong>the</strong>ir common Semitic origin in <strong>the</strong><br />

Phoenician phonetic alphabet.<br />

Understanding all <strong>the</strong> implic<strong>at</strong>ions and meaning th<strong>at</strong> calligraphy has<br />

had in Far Eastern cultures is not easy for us WeÌerners. By <strong>the</strong> same<br />

token, even if Arabic culture is much more similar to ours, we can<br />

speak <strong>of</strong> Arabic calligraphy only in very superficial terms.<br />

SIGISMONDO FANTE, Theorica et pr<strong>at</strong>ica, Venezia 1514<br />

XXVII

None<strong>the</strong>less, in lieu <strong>of</strong> explan<strong>at</strong>ions, I believe it is worthwhile proposing<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> aspects th<strong>at</strong> evoke <strong>the</strong> charms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se two marvellous<br />

worlds <strong>of</strong> calligraphy th<strong>at</strong> are not too far removed from <strong>the</strong> research<br />

conducted by several <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> artists in display here in Cittadella.<br />

First <strong>of</strong> all, <strong>the</strong> difference in <strong>the</strong> texts to which calligraphy has lent its<br />

<strong>at</strong>traction must be noted. In <strong>the</strong> Chinese and Japanese worlds, calligraphy<br />

was considered a manifeÌ<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> art in its own right, while <strong>the</strong><br />

texts were viewed purely as liter<strong>at</strong>ure, and poetry, in particular, found<br />

its expressive complementariness in <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> writing, or calligraphy.<br />

Arabic calligraphy is almost exclusively dedic<strong>at</strong>ed to religious<br />

faith.<br />

The surahs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Koran are written and re-written throughout <strong>the</strong><br />

surface and <strong>the</strong>ir meaning – known and memorized by heart – are<br />

renewed by <strong>the</strong> invention and rhythm <strong>of</strong> every re-edition. If, on <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>mes most dear to Western calligraphy were to be<br />

indic<strong>at</strong>ed, <strong>the</strong> selection would include <strong>the</strong> military, <strong>the</strong> religious<br />

and <strong>the</strong> moralistic-captional. One wonders if it is mere chance th<strong>at</strong><br />

one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most renowned types <strong>of</strong> Western calligraphy is known as<br />

“Cancelleresca”, with <strong>the</strong> allusions to <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> bureaucracy <strong>the</strong><br />

term contains. The transcrÔtion <strong>of</strong> moral formulas, dedic<strong>at</strong>ions to<br />

<strong>the</strong> high and mighty authorities and <strong>the</strong> praise <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir dynasties and<br />

exploits are among <strong>the</strong> topics to which Western calligraphy most commonly<br />

and willingly lent its letters.<br />

The charm and seduction <strong>of</strong> Far Eastern calligraphy – Japanese, to<br />

be specific – is skilfully depicted by GrÕnaway in his film entitled<br />

The Pillow Book, where <strong>the</strong> true leading protagonist is calligraphy. The<br />

film's title is taken from a literary work written around 1000 years ago<br />

by a Japanese courtesan, Sei Shonagon.<br />

The story told by Greenaway is a far cry from <strong>the</strong> contents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

book, a combin<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> reportage, diary, and novel <strong>of</strong> life <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Emperor's Court. Wh<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> two works share in common, however,<br />

is <strong>the</strong> <strong>at</strong>tention, interest, curiosity, presence, and significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

continual references to calligraphy.<br />

The same direÀor had previously evoked <strong>the</strong> charm <strong>of</strong> Western calligraphy<br />

in a film inspired by Shakespeare's Tempest entitled ProÍero's<br />

Book. In both films, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most important and suÎeÌive elements<br />

is <strong>the</strong> hand <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> calligrapher as filmed during <strong>the</strong> elegant dance<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> letters over <strong>the</strong> page. The hand in question is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> Brody<br />

Neuenschwander, <strong>the</strong> winner <strong>of</strong> this year's first edition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “<strong>Belle</strong><br />

<strong>Lettere</strong> Award”. The consistency <strong>of</strong> his work and <strong>the</strong> wealth <strong>of</strong> his<br />

inventions, and <strong>the</strong> choice <strong>of</strong> m<strong>at</strong>erials imported majestically combine<br />

<strong>the</strong> tension <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most intense visual research with <strong>the</strong> memory<br />

and allusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> past.<br />

ALBRECHT DÜRER, GERM ANY 1528<br />

XXVIII<br />

CALLIGRAPHY AND PLEASURE<br />

We shall return to <strong>the</strong> charm th<strong>at</strong> calligraphy has exerted over Japanese<br />

society. The five basic schools <strong>of</strong> Chinese calligraphy had already<br />

reached Japan by <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 4th Century. These five were completed<br />

by a completely Japanese vari<strong>at</strong>ion introduced during <strong>the</strong> 8th<br />

Century composed by kana characters, which were in net contrast with<br />

<strong>the</strong> ideograms <strong>of</strong> Chinese origin because <strong>the</strong>y expreÊed <strong>the</strong> sounds <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> language ra<strong>the</strong>r than concepts.<br />

Three types <strong>of</strong> kana were subsequently developed: manyogana, hiragana,<br />

and k<strong>at</strong>akana. Before this system gained dominance, a number <strong>of</strong><br />

Japanese poems were written in Chinese ideograms utilized phonetically,<br />

while o<strong>the</strong>r were written in Chinese characters used sometimes<br />

phonetically and o<strong>the</strong>r times ideographically, and it was from this<br />

l<strong>at</strong>ter th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> hiragana and k<strong>at</strong>akana scripts were derived by means <strong>of</strong><br />

drastic simplific<strong>at</strong>ions.<br />

Thanks to <strong>the</strong> fundamental contributions made by <strong>the</strong> Japanese<br />

noble-women, <strong>the</strong> hiragana script evolved into <strong>the</strong> elegant, proportioned<br />

and unique style <strong>of</strong> Japanese calligraphy. It is interesting to<br />

note, by <strong>the</strong> way, in regard to women and calligraphy, th<strong>at</strong> approxim<strong>at</strong>ely<br />

50% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work on display in Ciıadella this year was made by<br />

women artists.<br />

I am unable to provide an explan<strong>at</strong>ion for this positively singular<br />

fact, apart from saying th<strong>at</strong> for some unknown reason th<strong>at</strong> would be<br />

interesting to investig<strong>at</strong>e, today’s women find <strong>the</strong>mselves just as much<br />

<strong>at</strong> ease in this cre<strong>at</strong>ive medium as <strong>the</strong> Japanese noble-women so many<br />

centuries ago.<br />

In both Japanese and Chinese society, <strong>the</strong> meaning <strong>of</strong> written poetry<br />

cannot be completely expressed unless it is rendered in elegant calligraphy<br />

th<strong>at</strong> is consonant with <strong>the</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poem. In <strong>the</strong> same<br />

way th<strong>at</strong> a poetic text must be read with <strong>the</strong> right emphasis and scansion,<br />

a written text must be visually finished with skill and sensitivity.<br />

`is is an aspect th<strong>at</strong> is completely ignored by Western culture, in<br />

which <strong>the</strong> abstraction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> word is considered sufficient to transmit<br />

its content independently from <strong>the</strong> pictorial illustr<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual<br />

represent<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

Below, we provide some examples <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>at</strong>tention dedic<strong>at</strong>ed to calligraphy<br />

by <strong>the</strong> 10th Century Japanese Court th<strong>at</strong> show how its every<br />

aspect was appreci<strong>at</strong>ed, beginning with <strong>the</strong> selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> type and<br />

colour <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> paper. Such painstaking consider<strong>at</strong>ions are entirely<br />

lacking in our culture. Court life – as described by Sei Shonagon<br />

– was charaÀerized by a whirling exchange <strong>of</strong> letters, notes, poems,<br />

and poetic recitals and tournaments filled with oblique references to<br />

both ancient and modern poetry in which <strong>the</strong> ladies, courtesans, and<br />

intellectuals <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Court were requested not only to judge without<br />

hesit<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>the</strong> defects and values <strong>of</strong> each text, but also to<br />

respond in kind.<br />

We cite a few lines seleÀed <strong>at</strong> random:<br />

from Chapter 23<br />

…His Majesty <strong>the</strong>n recounted: «In <strong>the</strong> days <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Emperor Murakami lived<br />

Her Highness, <strong>the</strong> Lady-in Waiting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pavilion <strong>of</strong> Light, which as you<br />

certainly all know was <strong>the</strong> daughter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Gre<strong>at</strong> Minister <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> LeÓ Hand<br />

faction.<br />

When she was still a young princess, her fa<strong>the</strong>r instructed her with this command:<br />

“Practise, above all, calligraphy, and <strong>the</strong>n learn to play <strong>the</strong> sevenstringed<br />

koto […], and <strong>the</strong>n learn by heart all twenty volumes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> AntholoË<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ancient and Modern Japanese Poetry. Your educ<strong>at</strong>ion must be based on<br />

<strong>the</strong>se three cardinal points”.»

In Chapter 31, entitled “Pleasant things”<br />

To succÕd in wr⁄ing a leıer on fine, spotless Chinese paper with slender characters, despite<br />

<strong>the</strong> large tip <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brush.<br />

In Chapter 82<br />

…as I awaited who knows wh<strong>at</strong> wr⁄ten declar<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> love […], I took out <strong>the</strong> epistle and<br />

observed it closely: it was fine rice paper in a pale blue tint written with pure and harmonious<br />

characters, but <strong>the</strong> contents were unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely not such to cause my heart to tremble,<br />

inasmuch as <strong>the</strong> flowing meÊage was written in Chinese: «…in <strong>the</strong> season <strong>the</strong> flowers in<br />

<strong>the</strong> capital bloom, you stand behind <strong>the</strong> curtain <strong>of</strong> brocade» and below th<strong>at</strong>, in Japanese<br />

«Can you tell me how <strong>the</strong> poem continues?». Perplexed, I thought th<strong>at</strong> if only His<br />

Majesty were here, I could show <strong>the</strong> letter to him and request his advice, <strong>the</strong>reby avoiding<br />

committing humili<strong>at</strong>ing errors in an ambitious <strong>at</strong>tempt to follow suit.<br />

In Chapter 89, entitled “Refined Particulars”<br />

A letter written on light blue tinted rice paper and bound with recently budded utsugi<br />

branches [Japanese gardenia]… A letter sealed with violet paper, bound by a long cluster<br />

<strong>of</strong> wisteria flowers may also be said to be refined…<br />

In Chapter 133, where mention is made <strong>of</strong> a note Sei receives<br />

It was written in such a stupendous hand th<strong>at</strong> I immedi<strong>at</strong>ely went to show it to His Majesty,<br />

who praised it by saying «It is written marvellously well and is also elegant and humorous»<br />

[…] I <strong>the</strong>n whispered to His Majesty «How must I reply?», and sent a message<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> following <strong>words</strong> on flaming pink paper: «The servant who did not come to present<br />

me with this message personally seems an extremely cold man to me». I bound <strong>the</strong> paper<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> branch <strong>of</strong> a plum tree and sent it o°.<br />

In Chapter 138<br />

…when she opened it, she was amazed to see a hazel-nut coloured paper with a poem<br />

written in <strong>the</strong> stupendous calligraphy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> monks: «Once again I carry in memory this<br />

handful <strong>of</strong> flowers [<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> type used for <strong>the</strong> dyeing <strong>of</strong> mourning gowns] when <strong>the</strong> leaves are<br />

already turning colour in <strong>the</strong> capital [signiÃing th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> mourning period is over]».<br />

In Chapter 143<br />

…I opened it trembling uncontrollably: <strong>the</strong> page was white, but contained a petal <strong>of</strong> yamabuki<br />

flower on which <strong>the</strong> <strong>words</strong> «think without saying» were penned.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> fragments added to <strong>the</strong> appendix<br />

The colours th<strong>at</strong> I prefer in thin, fine-grain paper are white, violet, red, freshly-cut grass<br />

green, and sky blue.<br />

The box for writing must be th<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> lacquered wood with inserts <strong>of</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r-<strong>of</strong>-pearl and<br />

designs <strong>of</strong> clouds and birds.<br />

The best pens for <strong>the</strong> winter are those made with camel hair th<strong>at</strong> are easy to use and pretty<br />

to see, and also those <strong>of</strong> hare are good.<br />

The most precious ink sticks are <strong>the</strong> round ones.<br />

Compared to this continuous <strong>at</strong>tention for <strong>the</strong> ways, forms, and<br />

instruments <strong>of</strong> Far Eastern calligraphy, <strong>the</strong> only similar mention I<br />

have found in our tradition lies in a well-known sonnet by Guido<br />

Cavalcanti in which <strong>the</strong> tools <strong>of</strong> writing are transformed into <strong>the</strong><br />

interpreters and heralds <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poet's su°ering:<br />

We are <strong>the</strong> saddened pens,<br />

The aching scissors and knife<br />

Th<strong>at</strong> painfully transcribed<br />

The <strong>words</strong> you have heard.<br />

WANG WEI (1555–1636), A SINGLE<br />

CHARACTER IN A P OEM<br />

CALLIGRAPHY AND FAITH<br />

Fearful th<strong>at</strong> figur<strong>at</strong>ive art might encourage idol<strong>at</strong>ry, <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ocracy<br />

<strong>of</strong> Islam chose and promoted <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> calligraphy as <strong>the</strong> privileged<br />

form <strong>of</strong> reliÿous expression, where it is used primarily for <strong>the</strong> tireless<br />

repetition <strong>of</strong> prayers, and <strong>the</strong> writing and rewriting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> divine<br />

messages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Koran on every poßible surface. But in this rewriting,<br />

for as redundant and commonplace as <strong>the</strong> message might be, <strong>the</strong><br />

text is visually renewed through <strong>the</strong> abÌract beauty <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lines th<strong>at</strong><br />

constantly invent different ways to transmit <strong>the</strong> flowing energy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

letters and <strong>the</strong> blank spaces in between. The idea <strong>of</strong> this flow <strong>of</strong> energy<br />

shared by all works <strong>of</strong> Arabic calligraphy is not immedi<strong>at</strong>ely evident to<br />

<strong>the</strong> untrained eye more concerned perhaps with <strong>the</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

contents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> text. Wh<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> calligrapher writes is not as important<br />

as <strong>the</strong> way it is wr⁄ten. The control <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> energy th<strong>at</strong> will autom<strong>at</strong>ically<br />

guide <strong>the</strong> calligrapher in writing and th<strong>at</strong> is evident in <strong>the</strong> work<br />

is achieved through tireless repetition in which punctu<strong>at</strong>ion signs,<br />

letters, and <strong>words</strong>, recognizable or illegible, are repe<strong>at</strong>ed thousands<br />

<strong>of</strong> times and even superimposed over <strong>the</strong> same sheet, as in <strong>the</strong> Turkish<br />

practice known as karalama, talim, and mesk. One important aspect <strong>of</strong><br />

each exercise regards <strong>the</strong> control <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bre<strong>at</strong>h, which must be suited<br />

to follow <strong>the</strong> rhythm <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> writing, «<strong>the</strong> gestures <strong>of</strong> pushing or pulling<br />

will never be <strong>the</strong> same if performed while inhaling or exhaling.<br />

[…] If <strong>the</strong> calligrapher wants <strong>the</strong> line to remain pure, he must hold<br />

his bre<strong>at</strong>h […] <strong>the</strong> pauses in writing are precise and standardized<br />

and serve to fill <strong>the</strong> lungs with air and <strong>the</strong> pen with ink» (Ayah Issa<br />

Khassaf).<br />

Arabic calligraphy has its own rules <strong>of</strong> proportion for its letters, but<br />

<strong>the</strong>se all regard <strong>the</strong> interiors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> signs traced, and not <strong>the</strong> exteriors<br />

on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> abstract and absolute geometry revealed by <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>words</strong> <strong>of</strong> Tory. The Arabic rules are based on <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> alif (<strong>the</strong><br />

first letter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arabic alphabet, essentially a straight vertical sign),<br />

whose height, which varies depending on di°erent styles and calligraphies,<br />

can range from 3 to 12 points on <strong>the</strong> scale. The point, square<br />

in shape, was obtained by pressing <strong>the</strong> tip <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pen or brush on <strong>the</strong><br />

paper, and <strong>the</strong>refore depended on <strong>the</strong> way in which <strong>the</strong> ink-stand had<br />

been cut and <strong>the</strong> pressure exerted on <strong>the</strong> page. One important aspect<br />

<strong>of</strong> Arabic calligraphy is <strong>the</strong> expressive fullness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> empty volumes:<br />

every space, regardless <strong>of</strong> whe<strong>the</strong>r it is composed <strong>of</strong> characters or just<br />

<strong>the</strong> bottom <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> page, must find its own force. Gre<strong>at</strong> <strong>at</strong>tention is<br />

given to <strong>the</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ionship between <strong>the</strong> shape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> black letters and<br />

<strong>the</strong> forms th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> white spaces around <strong>the</strong>m aÊume. The control <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se rel<strong>at</strong>ional aspects is performed not only through <strong>the</strong> vari<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> shapes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> letters and <strong>the</strong> <strong>words</strong> but also through <strong>the</strong> vari<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir positions in space. Leıers and <strong>words</strong> can ei<strong>the</strong>r be condensed<br />

into dense and apparently intric<strong>at</strong>e knots or extended and stretched<br />

in length: <strong>the</strong>y can be folded to cre<strong>at</strong>e angles or used to design a curve<br />

in moments <strong>of</strong> balance continually loÌ and regained between <strong>the</strong><br />

force <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> st<strong>at</strong>ic forms and <strong>the</strong> dynamism <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> movement. While<br />

Western calligraphy rarely breaks <strong>the</strong> rule th<strong>at</strong> obliges characters and<br />

<strong>words</strong> to follow each o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>at</strong> equally measured intervals along horizontal<br />

lines positioned parallel on <strong>the</strong> page, Arabic calligraphy utilizes<br />

<strong>the</strong> space provided by <strong>the</strong> support with much gre<strong>at</strong>er freedom.<br />

Western calligraphy is based on a rigidly sequential concept <strong>of</strong> time,<br />

on a “beginning” th<strong>at</strong> starts <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> left and an “aÓerwards” th<strong>at</strong> lies<br />

progressively fur<strong>the</strong>r to <strong>the</strong> right. Arabic calligraphy, while having<br />

similar rules <strong>of</strong> its own where <strong>the</strong> only difference is th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> text reads<br />

from right to left, is much less restricted by such formalities and has<br />

gre<strong>at</strong>er freedom to ignore <strong>the</strong>m. Space grants cre<strong>at</strong>iviÙ all its direc-

MAGHRIBI, Koran, 1560<br />

tions, while present time makes no claims on <strong>the</strong> future. This is wh<strong>at</strong><br />

we see in <strong>the</strong> few examples available <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> karalama exercises mentioned<br />

previously. These works – which did not aspire to perfection,<br />

and whose purpose was not to exceed <strong>the</strong> works <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r calligraphers<br />

or <strong>the</strong>mselves in order to reach <strong>the</strong> highest heights <strong>of</strong> art because<br />

<strong>the</strong> letters and <strong>the</strong> <strong>words</strong> had been rendered illeÿble by being thickly<br />

written one <strong>at</strong>op <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r – come closer than ever to <strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong><br />

modern artistic research. These exercises, which may be rightly considered<br />

among <strong>the</strong> most important cre<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> calligraphers over<br />

<strong>the</strong> span <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> centuries are works <strong>of</strong> art in <strong>the</strong>mselves. We may agree<br />

with Ferit Edgü when he defines <strong>the</strong>m as absolute works <strong>of</strong> art in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

own right because <strong>the</strong>y express no intention <strong>of</strong> leading us anywhere<br />

and refer to no o<strong>the</strong>r meaning than <strong>the</strong>ir own. «These examples<br />

represent an obsessive rebellion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> letters, almost as if <strong>the</strong> speed<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hand th<strong>at</strong> cre<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>the</strong>m had been freed from <strong>the</strong> control <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

mind and human awareness.»<br />

More than a few <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> works on display Cittadella <strong>of</strong>fer similar<br />

analogies to <strong>the</strong> karalama writing. In <strong>the</strong> works <strong>of</strong> Jan Roald, Sandra<br />

Schilling, Kennedy Hansen, Michael Hiemann, Helga Ladurner, and<br />

Glen Epstein, Gerald Geffert, it is not diÇcult to see an analogous<br />

freedom <strong>of</strong> research, an occasionally complete independence from<br />

<strong>the</strong> text and its legibility accompanied by a complete submission to <strong>the</strong><br />

charm <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> letters and <strong>the</strong>ir construÀion. The leıers are redrawn,<br />

transformed, and str<strong>at</strong>ified into gre<strong>at</strong>er levels <strong>of</strong> depth, and distributed<br />

throughout space freed from <strong>the</strong> sequentiality <strong>of</strong> reading in a new<br />

“rebellion against literacy” th<strong>at</strong> is unprecedented in our tradition,<br />

but as we have seen, corrobor<strong>at</strong>ed by ancient and noble predecessors<br />

in <strong>the</strong> past.<br />

Modern aes<strong>the</strong>tic research, in its continual thrust to explore <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>st<br />

reaches <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> poßibilities <strong>of</strong> expression, has paradoxically now<br />

come closer to one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> richest and most fascin<strong>at</strong>ing arts <strong>of</strong> a culture<br />

to which we are in debt for many <strong>of</strong> its teachings.<br />

XXX<br />

CALLIGRAPHY, WRITING, AND ART<br />

We have already mentioned <strong>the</strong> fact<br />

th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> birth <strong>of</strong> writing preceded<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficial birth <strong>of</strong> Western calligraphy,<br />

but how exactly was writing<br />

born? This is no mere academic<br />

question, because we intend to<br />

show th<strong>at</strong> calligraphy has maintained<br />

something from its origin<br />

th<strong>at</strong> writing appears to have lost.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> <strong>words</strong> <strong>of</strong> Gelb, “Complete<br />

writing” is a means <strong>of</strong> expressing<br />

linguistic content through conventionalized<br />

visible signs. This is <strong>the</strong><br />

final end <strong>of</strong> long journey achieved<br />

by all forms <strong>of</strong> writing th<strong>at</strong> have<br />

reached <strong>the</strong> st<strong>at</strong>e <strong>of</strong> “completion”.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> writing lies visual<br />

perception, th<strong>at</strong> cognitive process<br />

through which awareness <strong>of</strong> our<br />

surroundings is instilled inside us<br />

– here and now – through which<br />

we learn very quickly to interpret<br />

and recognize both permanence<br />

and changing phenomena. We must recall th<strong>at</strong> homo sapiens, <strong>at</strong> a certain<br />

point during its prehistory, included among its “permanencies” th<strong>at</strong><br />

stimul<strong>at</strong>ed memory even a number <strong>of</strong> signs th<strong>at</strong> it left ei<strong>the</strong>r accidentally<br />

or intentionally in <strong>the</strong> places it lived.<br />

In Europe, <strong>the</strong> earliest traces d<strong>at</strong>e back to 30.000 years B.C., and<br />

include <strong>the</strong> first drawings th<strong>at</strong> human beings both figur<strong>at</strong>ively and<br />

abstractly painted on <strong>the</strong> walls <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir caves. The first blooming <strong>of</strong><br />

n<strong>at</strong>uralistic cave art occurred around 25.000 B.C., and includes a vast<br />

production <strong>of</strong> figures th<strong>at</strong> were not rarely drawn with skill and verisimilitude.<br />

Although it is very hard to say with precision just why human<br />

beings began drawing or etching figures, we might think <strong>of</strong> magic,<br />

religious, or aes<strong>the</strong>tic reasons, while also considering motives <strong>of</strong> commemor<strong>at</strong>ion,<br />

joy in existence, and narr<strong>at</strong>ion. The <strong>pleasure</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

display <strong>of</strong> uncommon artistry th<strong>at</strong> produces admir<strong>at</strong>ion in o<strong>the</strong>rs and<br />

which today we refer to as <strong>the</strong> artistic impulse could not certainly have<br />

been far removed from <strong>the</strong>se first performances. Communic<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

based on seeing is <strong>the</strong>refore independent <strong>of</strong> speaking, and becomes<br />

possible when <strong>the</strong> convention is established th<strong>at</strong> it is comprehensible<br />

not only to its authors, but to o<strong>the</strong>rs who share <strong>at</strong> least part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

same experience as well.<br />

At <strong>the</strong> start, writing was only an approxim<strong>at</strong>ive <strong>at</strong>tempt <strong>at</strong> communic<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

through images. Its aßoci<strong>at</strong>ion with <strong>words</strong> was only vague and<br />

occasional. The written message did not entirely reflect <strong>the</strong> forms<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spoken language. Even if <strong>the</strong> message had a clear and unique<br />

meaning, it could be verbalized in many different forms by whoever<br />

happened to read it. Writing progressively evolved into a precise system<br />

for <strong>the</strong> transcription <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sounds issued by <strong>the</strong> tongue, or language.<br />

Writing became a system th<strong>at</strong> guarantÕd <strong>the</strong> conserv<strong>at</strong>ion, without<br />

alter<strong>at</strong>ion, <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> concepts expressed and <strong>the</strong> gramm<strong>at</strong>ical and<br />

syntactical struÀure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> language spoken and <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong>ir recall<br />

and e°ectiveness l<strong>at</strong>er on in time.<br />

By subjecting itself almost entirely to <strong>the</strong> service <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spoken word,<br />

writing gained gre<strong>at</strong> precision, on one hand, but lost its independence,<br />

on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. It is stimul<strong>at</strong>ing, although perhaps not completely<br />

true, to think th<strong>at</strong> calligraphy is <strong>the</strong> component <strong>of</strong> writing th<strong>at</strong> has<br />

inherited this ancient independence from <strong>the</strong> word. `is explains why<br />

calligraphy has <strong>of</strong>ten sÕmed so willing to amuse itself <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> expense <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>words</strong>, twisting <strong>the</strong>m around and intentionally making <strong>the</strong>m harder to<br />

“understand”. This arises from <strong>the</strong> need to permit writing to regain<br />

gre<strong>at</strong>er space for its visual components, while reducing verbal content<br />

(<strong>the</strong> verbal ones).<br />

`is objeÀive is artfully achieved when calligraphy succeeds in seducing,<br />

with <strong>the</strong> enchanting spell woven by its forms, <strong>the</strong> total <strong>at</strong>tention <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> viewer, carrying her or him fur<strong>the</strong>r away from <strong>the</strong> text.<br />

The complic<strong>at</strong>ed rel<strong>at</strong>ionship between writing and calligraphy is due to<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir common origins, followed by <strong>the</strong>ir di°erent ends. Gelb speaks<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir origins thus: «…The visual image is <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> all writing.<br />

This is evident not only due to <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> all modern primitive writings<br />

are picturesque in <strong>the</strong>ir charaÀers, but also because all <strong>the</strong> gre<strong>at</strong><br />

Oriental syÌems such as Sumeric, Egyptian, Hittite and Chinese, etc.<br />

were originally written with images, or ideograms».<br />

All <strong>the</strong> well-developed forms <strong>of</strong> writing have two types <strong>of</strong> character:<br />

one is <strong>the</strong> “formal script”, used in public monuments and <strong>of</strong>ficial<br />

documents and executed with careful <strong>at</strong>tention; <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r “cursive”<br />

script is usually used in priv<strong>at</strong>e, and much more brusque, and fe<strong>at</strong>ures<br />

numerous abbrevi<strong>at</strong>ions and more schem<strong>at</strong>ic characters. Already in<br />

ancient Egypt, hieroglyphic writing was used primarily for display to<br />

<strong>the</strong> public, while two cursive scripts, <strong>the</strong> “solemn, or st<strong>at</strong>ely”, and <strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong> “demotic” were developed.

The aes<strong>the</strong>tic aspect receives gre<strong>at</strong>er <strong>at</strong>tention in formal scripts, which<br />

are also more conserv<strong>at</strong>ive, and continue to preserve in <strong>the</strong> shapes <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir charaÀers <strong>the</strong> memory <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> figur<strong>at</strong>ive forms from which <strong>the</strong>y<br />

had origin<strong>at</strong>ed.<br />

Cursive scripts utilize linear forms in which <strong>the</strong> original pictorial<br />

components are no longer recognizable.<br />

In Western calligraphy, after its rebirth in <strong>the</strong> Renaißance and<br />

<strong>the</strong> geometric tailoring <strong>of</strong> its Roman “formal script”, <strong>the</strong> invention,<br />

development and virtuoso exhibition <strong>of</strong> its manual cursive<br />

script characterized <strong>the</strong> Baroque Period. Renaissance calligraphers<br />

had opened two fronts <strong>of</strong> interesting research in <strong>the</strong> visual form <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> writing: <strong>the</strong>y cast <strong>the</strong> basis and established <strong>the</strong> criteria for <strong>the</strong><br />

design <strong>of</strong> today's print charaÀers, criteria th<strong>at</strong> are still observed<br />

today by graphic designers; and <strong>the</strong>y re-organized and perfected <strong>the</strong><br />

Chancellery-type cursive script from which <strong>the</strong> funambul<strong>at</strong>ory play<br />

<strong>of</strong> Baroque calligraphy ensued. The two opposing tendencies th<strong>at</strong><br />

characterize <strong>the</strong> visual components <strong>of</strong> writing as a function <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> legibility<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> text are derived from <strong>the</strong>se two fronts. The first tendency<br />

is totally dedic<strong>at</strong>ed to <strong>the</strong> text, its legibility, and <strong>the</strong> elimin<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong><br />

any and all visual background noise. This is a type <strong>of</strong> homogeneous,<br />

public writing th<strong>at</strong> spurs any form <strong>of</strong> ostent<strong>at</strong>ion, and aspires <strong>at</strong> invisibility<br />

owing to its uniformity, which is not structured to <strong>at</strong>tract <strong>the</strong><br />

reader's aıention, in full awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> less <strong>the</strong> letters<br />

in <strong>the</strong> <strong>words</strong> written are seen, <strong>the</strong> more <strong>the</strong> contents evoked by <strong>the</strong><br />

letters will be understood, and all <strong>the</strong> more better will <strong>the</strong> writing<br />

have done its job. This is <strong>the</strong> cold and indifferent writing, repetitive<br />

and constant in which books and <strong>the</strong> articles in newspapers – but not<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir titles – are written.<br />

The second tendency is, instead, exhibitionist, innov<strong>at</strong>ive, variable,<br />

and wants to <strong>at</strong>tract <strong>the</strong> <strong>at</strong>tention <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> reader to its own forms more<br />

than <strong>the</strong> contents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> text. This tendency loves ambiguity and<br />

unexpected, and <strong>the</strong> more bl<strong>at</strong>ant and <strong>the</strong>refore visible – but not necessarily<br />

legible – <strong>the</strong> masquerade <strong>of</strong> its letters is, <strong>the</strong> gre<strong>at</strong>er appreci<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

it will win. It is unstable; on <strong>the</strong> contrary, it plays <strong>at</strong> hiding itself<br />

SÜLÜS KARALAMA, ISTANBUL 1731(?)<br />

in illegibility and <strong>the</strong>n re-emerging into meaning. This is <strong>the</strong> writing<br />

th<strong>at</strong> fights with itself in advertising graphic, and also <strong>the</strong> writing th<strong>at</strong><br />

occupies <strong>the</strong> hazy confines <strong>of</strong> modern calligraphy – an area in which<br />

medit<strong>at</strong>ion and visual invention are cultiv<strong>at</strong>ed, and one which also<br />

raises <strong>the</strong> questions on <strong>the</strong> role th<strong>at</strong> calligraphy is still capable <strong>of</strong> playing<br />

in <strong>the</strong> fields <strong>of</strong> art and communic<strong>at</strong>ion.<br />

The works collected here in Ciıadella o°er ample and convincing<br />

testimony th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong>se question and medit<strong>at</strong>ions are still alive today.<br />

The accur<strong>at</strong>e and intelligent classific<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> works performed<br />

by Thomas Ingmire th<strong>at</strong> will accompany <strong>the</strong> reader in <strong>the</strong>se next few<br />

pages provides a handy guide to orient<strong>at</strong>ion in <strong>the</strong> complex terrain<br />

inhabited by both art and calligrafy.<br />

This final card began from very, very far away, <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> dawn <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

origins <strong>of</strong> writing, nay, fur<strong>the</strong>r yet, <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> painting and art itself.<br />

Writing, thus, was a product, a consequence <strong>of</strong> visual art. `roughout<br />

its long life, it has certainly changed and evolved autonomously, but<br />

never completely independently <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> routes taken and developments<br />

made by visual art.<br />

The area in which writing has preferred to develop and cultiv<strong>at</strong>e its<br />

research and ¬s<strong>the</strong>tic ambitions is calligraphy. This context has up<br />

until recent times bÕn kept separ<strong>at</strong>e and independent Ïom painting<br />

and <strong>the</strong> gre<strong>at</strong>er fine arts, both because calligraphy has always bÕn<br />

considered a minor art, and also because <strong>the</strong> calligraphers have cultiv<strong>at</strong>ed<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir independence on <strong>the</strong>ir own, due to <strong>the</strong> ample gr<strong>at</strong>ific<strong>at</strong>ion<br />

<strong>the</strong>y have always found in <strong>the</strong>ir work.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> artistic Avant-garde <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1900s first broke down <strong>the</strong> barriers<br />

between various seÀors <strong>of</strong> artistic research, writing, on one hand<br />

(see <strong>the</strong> contribution to this volume by Tiziano Santi), and calligraphy,<br />

on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r returned as protagonists in <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual<br />

arts in which <strong>the</strong>y first saw <strong>the</strong> light over 5000 years ago. Thus, <strong>the</strong><br />

circle closes again, but not without doubt, conflict and uncertainty.<br />

The Cittadella Exhibition is a particip<strong>at</strong>ory and well-informed witness<br />

to <strong>the</strong>se tensions and <strong>the</strong>ir expansion in every direction. Between<br />

<strong>the</strong> hyper-realistic and slightly obsessive reconstruction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sabo-<br />

XXXI

taged Medieval code performed by Keith Adams, and <strong>the</strong> complete<br />

renunci<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> characters, whose absence is displayed by <strong>the</strong> orphan<br />

and abstract page-making executed by Piero Brombin, <strong>the</strong> wide<br />

range <strong>of</strong> rel<strong>at</strong>ionship th<strong>at</strong> modern calligraphers enjoy with <strong>the</strong> text<br />

is presented. We can only hope th<strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cittadella Exhib⁄ion remain<br />

a privileged and aıentive observer for <strong>the</strong> continuous revision and<br />

growth <strong>of</strong> this C<strong>at</strong>alogue.<br />

It has all <strong>the</strong> cards in hands to do so.<br />

IL PIACERE DI MOSTRARE E GUARDARE<br />

LE PAROLE<br />

di Manfredo Massironi<br />

L’ENTRATA<br />

La calligrafia ha sempre avuto rapporti complic<strong>at</strong>i e diagonali con molti degli eventi<br />

– processi, scoperte, tecniche, arti – con cui si è trov<strong>at</strong>a a convivere o almeno ad interagire.<br />

Questi rapporti sempre un po’ sfas<strong>at</strong>i riguardano:<br />

1. I rapporti con il testo – scrittura e leıura – e quindi con la stampa, spesso dialettici, a<br />

volte conflittuali.<br />

2. I legami di parentela con l’arte, e quindi le frequenti relazioni di contiguità con l’espressività,<br />

la comunicazione e la ricerca estetica.<br />

3. I rapporti di funzionalità diversa a culture diverse.<br />

Non è possibile, per la vastità dell’argomento e per i limiti delle mie competenze, una tr<strong>at</strong>tazione<br />

sistem<strong>at</strong>ica delle complic<strong>at</strong>e questioni riassunte nei tre punti elenc<strong>at</strong>i. La stesura<br />

di alcune “schede” in cui verranno tr<strong>at</strong>t<strong>at</strong>i, in maniera asistem<strong>at</strong>ica, alcuni degli aspetti<br />

problem<strong>at</strong>ici sopra elenc<strong>at</strong>i, costituirà allora per me una sorta di utile scapp<strong>at</strong>oia, in cui<br />

privilegiare momenti particolari e curiosi, nel tent<strong>at</strong>ivo di coltivare quella “leÎerezza” che<br />

Calvino a°erma essere prerog<strong>at</strong>iva della buona leıer<strong>at</strong>ura, e che io ritengo sia anche uno<br />

dei modi e dei pregi della calligrafia.<br />

GLI INIZI, MA NON L’INIZIO<br />

Una prima singolarità della calligrafia riguarda la sua nascita “uÇciale”, che avvenne<br />

in epoca rinascimentale. Possiamo tutti ben immaginare che la calligrafia fosse già bell’e<br />

n<strong>at</strong>a allorché, con la consapevolezza delle loro scoperte e invenzioni, con la sicurezza<br />

delle loro geometrie e la verità delle loro proporzioni, gli artisti e gli umanisti italiani del<br />

Rinascimento ne decretarono la nascita. Probabilmente nei 4500 anni circa che separano<br />

la comparsa della scrittura dalla nascita della calligrafia moderna, il termine “scrittura”<br />

era anche sinonimo di “calligrafia”. Non a caso, inf<strong>at</strong>ti, i nuovi calligrafi rinascimentali,<br />

che non vivevano più nelle celle dei conventi, si dedicarono con passione alla riscoperta e<br />

reinvenzione della scrittura dell’antichità classica.<br />

La seconda singolarità è che la nascita della calligrafia sia coincisa proprio con il diffondersi<br />

della tecnica e dell’arte della stampa, che, a rigor di logica, ne avrebbe dovuto<br />

decretare l’inutilità, e quindi la fine. I nuovi car<strong>at</strong>teri che, una volta costruiti, erano riutilizzabili<br />

indipendentemente dall’abilità grafica del tipografo, avrebbero dovuto ridurre lo<br />

spazio d’azione e di ricerca del calligrafo. Invece avvenne il contrario.<br />

I calligrafi, e tra i primi quelli italiani, fornirono agli stamp<strong>at</strong>ori tedeschi che erano giunti<br />

in Italia nuovi, eleganti e proporzion<strong>at</strong>i car<strong>at</strong>teri, con cui sostituire quelli approßim<strong>at</strong>ivi e<br />

ineleganti delle produzioni iniziali.<br />

L’opera forse più antica che ci sia giunta, in cui la costruzione geometrica delle lettere<br />

è condotta sulla base del quadr<strong>at</strong>o e del cerchio, si deve all’umanista veronese Felice<br />

Feliciano, che derivò i suoi car<strong>at</strong>teri, pubblic<strong>at</strong>i nel 1463, dallo studio delle iscrizioni<br />

romane. Grazie ad uno di quei lungimiranti meccanismi della storia – quelli che fanno<br />

XXXII<br />

Letters from <strong>the</strong> alphabet <strong>of</strong> Antonotius<br />

andare le cose in maniera diversa da come la miopia della nostra logica potrebbe ritenere<br />

– accadde che l’avvento della stampa promoÊe, anziché inibire, la produzione e la divulgazione<br />

dei manuali di calligrafia. La stampa, dil<strong>at</strong>ando l’o°erta di leıura, incrementò la<br />

richiesta di accesso alla scr⁄tura.<br />

La scrittura era per gli umanisti uno strumento, la cui bellezza, utilità e decoro poggiavano<br />

sulle proporzioni, cioè su quelle relazioni nascoste di tipo aritmetico-geometrico destin<strong>at</strong>e<br />

a rivelare la perfezione e l’armonia che regola l’universo, dalle sfere celesti alle lettere dell’alfabeto.<br />

Artisti e scienzi<strong>at</strong>i fra i più importanti del Rinascimento, come Leon B<strong>at</strong>tista<br />

Alberti, Luca Pacioli, Albrecht Dürer, si dedicarono con impegno al disegno e<br />

all’architettura dei car<strong>at</strong>teri. I maestri calligrafi veri e propri, come ad esempio Ludovico<br />

Arrighi detto Vicentino, sistem<strong>at</strong>izz<strong>at</strong>ore della scrittura Cancelleresca, e Sigismondo<br />

Fante da Ferrara, estensore di un importante tr<strong>at</strong>t<strong>at</strong>o, pubblic<strong>at</strong>o nel 1514, sulle forme e<br />

proporzioni delle principali scritture, misero a punto testi basilari sulle regole geometriche<br />

che governano il disegno dei car<strong>at</strong>teri, che costituirono il punto di riferimento per tutta<br />

Europa. Ma i numeri, così come le corrispondenze geometriche che rassicurano le nostre<br />

scelte, erano individu<strong>at</strong>i e manipol<strong>at</strong>i dai disegn<strong>at</strong>ori rinascimentali sulla base di giustificazioni<br />

esoteriche, mitologiche e astrologiche.<br />

Ma le scelte oper<strong>at</strong>e in base alla magia e al mistero si reggono solo grazie al sostegno della<br />

fede. E le spiegazioni dett<strong>at</strong>e dalla fede possono permettersi il lusso di essere razionalmente<br />

inconsistenti. Questo <strong>at</strong>teggiamento – insieme alla dimostrazione che il libro di Fante,<br />

÷eorica et pr<strong>at</strong>ica, era divent<strong>at</strong>o un punto di riferimento per i calligrafi europei del-

l’epoca – si ritrova nella divertente polemica che il calligrafo francese Ge<strong>of</strong>roy Tory,<br />

nel bel libro intitol<strong>at</strong>o Champ Fleury, sostiene nei confronti del Pacioli, del Fante e del<br />

Vicentino. Il volume di Tory tr<strong>at</strong>ta «L’Arte e scienza delle appropri<strong>at</strong>e e vere proporzioni<br />

delle lettere <strong>at</strong>tiche, che sono altrimenti chiam<strong>at</strong>e lettere antiche e nel linguaÎio comune<br />

lettere romane». Tory sostiene che fr<strong>at</strong>e Luca Pacioli aveva disegn<strong>at</strong>o lettere aıiche senza<br />

dir niente su di esse e senza dare spiegazioni del suo metodo: non c’era di che meravigliarsi,<br />

argomentava il Tory, dal momento che aveva sentito dire che il Pacioli aveva sottr<strong>at</strong>to<br />

quelle lettere al vecchio Leonardo da Vinci, morto da poco ad Amboise. Si capiva così perché<br />

le lettere del fr<strong>at</strong>e non erano disegn<strong>at</strong>e nelle giuste proporzioni, quelle che egli avrebbe<br />

present<strong>at</strong>o nel suo libro. Allo stesso modo, le lettere classiche non erano st<strong>at</strong>e disegn<strong>at</strong>e<br />

correttamente – per Tory – né da Sigismondo Fante né da Ludovico Vicentino. Dichiarava<br />

inoltre di non sapere se Dürer avesse spieg<strong>at</strong>o le sue teorie, ma che era certo che avesse sbagli<strong>at</strong>o<br />

le proporzioni di numerose delle lettere present<strong>at</strong>e nel libro sulla prospettiva.<br />

Lo stesso argomento viene in seguito ripreso e comment<strong>at</strong>o tecnicamente. Dopo aver spieg<strong>at</strong>o<br />

come deve essere disegn<strong>at</strong>a la lettera A, così ÿuÌifica la sua scelta:<br />

…come ho già detto, la A, se deve essere f<strong>at</strong>ta in accordo con l’arte,<br />

deve avere la gamba destra spessa quanto la decima parte dell’altezza,<br />

che è la larghezza di una delle dieci unità contenute fra le undici<br />

linee equidistanti disegn<strong>at</strong>e nel suo quadr<strong>at</strong>o, e non spessa come la<br />

nona parte della sua altezza come dice fr<strong>at</strong>e Luca Pacioli da Borgo San<br />

Sepolcro nella Divina proportione che egli afferma di aver scritto. Le sue<br />

proprie parole in italiano volgare sono le seguenti: Questa letera A si cava<br />

del tondo, e del suo quadro. La gamba da man drita vol esser grossa de la nove parti luna<br />

de lalteza. Egli divide il quadr<strong>at</strong>o in sole nove parti e non dà ragione di<br />

questo; e perciò dal punto di vista della correttezza a me sembra che<br />

parli da ignorante, andando fuori strada già dalla prima lettera per<br />

poi proseguire col resto […] Sigismondo Fante, un nobile di Ferrara,<br />

il quale, come ho detto, si sforza di insegnare come fare diversi tipi di<br />

lettere, non dà ragioni delle proporzioni delle sue così dette lettere,<br />

specialmente per le lettere Antiche. Anch’egli è and<strong>at</strong>o fuori strada<br />

nella A, la E, la L, la Q, la S, la T, e la X, che non sono f<strong>at</strong>te come<br />

dovrebbero, sia per dimensioni, che per forma. L’occhio <strong>at</strong>tento<br />

dello studioso esperto sarà certo in grado di percepire tutto questo nel<br />

libro che il detto Sigismondo ha stamp<strong>at</strong>o, intitol<strong>at</strong>o Theorica et pr<strong>at</strong>ica.<br />

Ma quali sono gli elementi su cui Tory basa le sue certezze? Ne troviamo un esempio alla<br />

fine del terzo libro, quando, spiegando come si disegnano i car<strong>at</strong>teri di interpunzione,<br />

a◊erma:<br />

SIGISMONDO FANTE, Theorica et pr<strong>at</strong>ica, Venezia 1514<br />

A questo punto descrivo<br />

e disegno solo tre<br />

tipi di punti, in accordo<br />

con l’uso degli antichi<br />

e in accordo con quanto<br />

richiesto dalle lettere<br />

<strong>at</strong>tiche, essendo del tutto<br />

consapevole che gli scrittori<br />

di gramm<strong>at</strong>ica della<br />

lingua l<strong>at</strong>ina tr<strong>at</strong>tano di<br />

numerosi altri punti, di<br />

cui Aulo Antonio Arobbio<br />

menziona 11 punti differenti,<br />

che sono: Punctum<br />

suspensivum, Geminum punctum,<br />

Semipunctum, Hypopliroma,<br />

Comma, Colon, Periodus,<br />

Interrog<strong>at</strong>ivum, Responsivum,<br />

Admir<strong>at</strong>ivum, & Paren<strong>the</strong>sis.<br />

Tutti questi, nel numero di undici, segretamente e nello stile divino,<br />

mi confermano che io ho giustamente diviso il mio quadr<strong>at</strong>o<br />

entro cui costruire le lettere <strong>at</strong>tiche in undici punti, da cui deriva in<br />

maniera manifesta che non sono and<strong>at</strong>o fuori strada, ma che ho scoperto<br />

con certezza e studio il segreto dei numeri pari e dispari, cioè<br />

di undici punti che comprendono dieci unità uguali come richiesto<br />

dalla divinità e dall’opinione fino ad ora pr<strong>at</strong>icamente sconosciuta<br />

degli antichi eccellenti.<br />

Il tempo in cui si poteva polemizzare<br />

aspramente sul f<strong>at</strong>to se il quadr<strong>at</strong>o in cui<br />

disegnare le lettere dovesse essere diviso in<br />

nove o in undici parti è decisamente lontano.<br />

Le certezze che si è disposti a sostenere<br />

a tutti i costi sono sempre meno, e non solo<br />

rel<strong>at</strong>ivamente agli schemi geometrici entro<br />

cui disegnare le lettere dell’alfabeto. Non<br />

c’è nessun rimpianto in questa const<strong>at</strong>azione,<br />

nessuna nostalgia per le certezze<br />

perdute, anche se qualche piccola certezza,<br />

qua e là, costituisce un sostegno che ci può<br />

aiutare a stare in piedi. Dobbiamo abituarci<br />

perciò a confidare solo nelle piccole<br />

certezze e a diffidare sempre delle grandi.<br />

Le opere esposte a Cittadella e raccolte<br />

in questo volume sono una testimonianza<br />

evidente di questo st<strong>at</strong>o di cose. Accanto a<br />

lavori che si rifanno alle forme e ai contenuti<br />

della calligrafia classica, riproposti<br />

nelle personali versioni degli autori con il<br />

piacere di riscoprirne e riviverne l’armonia<br />

interna, vi sono opere in cui le lettere e la<br />

scrittura vanno alla ricerca di m<strong>at</strong>eriali<br />

diversi, non più la penna e l’inchiostro, di<br />

supporti nuovi, non più il foglio di carta,<br />

opere in cui il testo si concede ancora, anche se a malincuore, alla lettura. Tutti sanno<br />