Working Paper of Public Health Volume 2012 - Azienda Ospedaliera ...

Working Paper of Public Health Volume 2012 - Azienda Ospedaliera ...

Working Paper of Public Health Volume 2012 - Azienda Ospedaliera ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

La serie di <strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> (WP) dell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong>di Alessandria è una serie di pubblicazioni online ed Open Access,progressiva e multi disciplinare in <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong> (ISSN: 2279-9761). Virientrano pertanto sia contributi di medicina ed epidemiologia, sia contributidi economia sanitaria e management, etica e diritto. Rientra nella politicaaziendale tutto quello che può proteggere e migliorare la salute dellacomunità attraverso l’educazione e la promozione di stili di vita, così comela prevenzione di malattie ed infezioni, nonché il miglioramentodell’assistenza (sia medica sia infermieristica) e della cura del paziente. Siprefigge quindi l’obiettivo scientifico di migliorare lo stato di salute degliindividui e/o pazienti, sia attraverso la prevenzione di quanto potrebbecondizionarla sia mediante l’assistenza medica e/o infermieristicafinalizzata al ripristino della stessa.Gli articoli pubblicati impegnano esclusivamente gli autori, le opinioniespresse non implicano alcuna responsabilità da parte dell'<strong>Azienda</strong><strong>Ospedaliera</strong> “SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo” di Alessandria.La pubblicazione è presente in: Directory <strong>of</strong> Open Access Journals (DOAJ);Google Scholar; Academic Journals Database;Comitato Scientifico:Dr. Nicola Giorgione (Presidente)Dr. Luciano Bernini (Vice-Presidente)Dr. Francesco ArenaDr. Massimo DesperatiDr. Carlo ArfiniDr. Ivo CasagrandaDr. Gabriele FerrettiDr.ssa Lorella GambariniDr. Francesco MusanteDr. Claudio PesceDr. Fernando PesceDr. Salvatore PetrozzinoDr. Giuseppe SpinoglioComitato di Direzione:Dr. Antonio MaconiDr. Ennio PiantatoResponsabile:Dr. Antonio Maconitelefono: +39.0131.206818email: amaconi@ospedale.al.itSegreteria:Roberto Ippoliti, Ph.D.telefono: +39.0131.206819email: rippoliti@ospedale.al.itNorme editoriali:Le pubblicazioni potranno essere sia in lingua italiana sia in lingua inglese,a discrezione dell’autore. Sarà garantita la sottomissione di manoscritti atutti coloro che desiderano pubblicare un proprio lavoro scientifico nellaserie di WP dell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> di Alessandria, purché rientrino nellelinee guida editoriali. Il Responsabile Scientifico di redazione verificheràche gli articoli sottomessi rispondano ai criteri editoriali richiesti. Nel casoin cui lo si ritenga necessario, lo stesso Responsabile valuterà l’opportunitào meno di una revisione a studiosi o ad altri esperti, che potrebbero o menoaver già espresso la loro disponibilità ad essere revisori per il WP (i.e. peerreview). L’utilizzo del peer review costringerà gli autori ad adeguarsi aimigliori standard di qualità della loro disciplina, così come ai requisitispecifici del WP. Con questo approccio, si sottopone il lavoro o le idee di unautore allo scrutinio di uno o più esperti del medesimo settore. Ognuno diquesti esperti fornirà una propria valutazione, includendo anche suggerimentiper l'eventuale miglioramento, all’autore, così come una raccomandazioneesplicita al Responsabile Scientifico su cosa fare del manoscritto (i.e.accepted o rejected).Al fine di rispettare criteri di scientificità nel lavoro proposto, la revisione saràanonima, così come l’articolo revisionato (i.e. double blinded).Diritto di critica:Eventuali osservazioni e suggerimenti a quanto pubblicato, dopo opportunavalutazione di attinenza, sarà trasmessa agli autori e pubblicata on line inapposita sezione ad essa dedicata.Questa iniziativa assume importanza nel confronto scientifico poiché stimolala dialettica e arricchisce il dibattito su temi d’interesse. Ciascunpr<strong>of</strong>essionista avrà il diritto di sostenere, con argomentazioni, la validità delleproprie osservazioni rispetto ai lavori pubblicati sui <strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong><strong>Health</strong>.Nel dettaglio, le norme a cui gli autori devono attenersi sono le seguenti:I manoscritti devono essere inviati alla Segreteria esclusivamente informato elettronico all’indirizzo e-mail dedicato (i.erippoliti@ospedale.al.it);A discrezione degli autori, gli articoli possono essere in lingua italiana oinglese. Nel caso in cui il manoscritto è in lingua italiana, è possibileaccompagnare il testo con due riassunti: uno in inglese ed uno initaliano, così come il titolo;Ogni articolo deve indicare, se applicabile, i codici di classificazioneJEL (scaricabili al sito: http://www.econlit.org/subject_descriptors.html)e le Keywords, nonché il tipo di articolo (i.e. Original Articles, BriefReports oppure Research Reviews;L’abstract è il riassunto dell’articolo proposto, pertanto dovrà indicarechiaramente: Obiettivi; Metodologia; Risultati; Conclusioni;Gli articoli dovrebbero rispettare i seguenti formati: Original Articles(4000 parole max., abstract 180 parole max., 40 references max.); BriefReports (2000 parole max., abstract 120 parole max., 20 referencesmax., 2 tabelle o figure) oppure Research Reviews (3500-5000 parole,fino a 60 references e 6 tabelle e figure);I testi vanno inviati in formato Word (Times New Roman, 12, interlinea1.5). Le note, che vanno battute in apice, non possono contenereesclusivamente riferimenti bibliografici. Inoltre, la numerazione deveessere progressiva;I riferimenti bibliografici vanno inseriti nel testo riportando il cognomedell’Autore e l’anno di pubblicazione (e.g. Calabresi, 1969). Nel caso dipiù Autori, indicare nel testo il cognome del primo aggiungendo et al;tutti gli altri Autori verranno citati nei riferimenti bibliografici alla finedel testo.I riferimenti bibliografici vanno elencati alla fine del testo in ordinealfabetico (e cronologico per più opere dello stesso Autore).Nel sottomettere un manoscritto alla segreteria di redazione, l'autore accettatutte le norme quì indicate.

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>Titolo: Indicatori bibliometrici ed efficienza ospedaliera, a Data Envelopment AnalysisAutori: Maconi Antonio; 1 Ippoliti Roberto; 1*†Tipo: Original ArticleJEL code: I120 - <strong>Health</strong> ProductionKeywords: Impact Factor; Scimago Impact Factor; Data Envelopment Analysis;AbstractObiettivi: Questo lavoro si propone di valutare la performance di strutture operative di un’<strong>Azienda</strong><strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale nella produzione scientifica.Metodologia: Dopo un’accurata presentazione dell’attività scientifica aziendale, è stata applicata lametodologia Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) in modo da poter ottenere un rankingdelle strutture operative aziendali tenuto conto dell’attività clinica eseguita.Risultati: Il ranking delle strutture operative non solo è condizionato dagli indicatori bibliometriciadottati, ma anche dalla normalizzazione del dato.Conclusioni: Al fine di eseguire una valutazione comparata delle strutture su più obiettivi, l’utilizzodella DEA risulta uno strumento appropriato per la Direzione Generale dell’<strong>Azienda</strong><strong>Ospedaliera</strong>.1 S.S.A. SVILUPPO E PROMOZIONE SCIENTIFICAA.O. “SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo” di AlessandriaTel: 0131/206818E-mail: amaconi@ospedale.al.it; rippoliti@ospedale.al.it;* Autore per la corrispondenza† Gli autori desiderano ringraziare la Dr.ssa M. Bertolotti per la raccolta dei dati relativi alla produzione scientifica dell’A.O. “SS. Antonio e Biagio eCesare Arrigo” di Alessandria.1

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>1. IntroduzioneGli indicatori bibliometrici sono strumenti di uso sempre più comune, universalmente accettati etalvolta imprescindibili nella valutazione su larga scala di riviste scientifiche, di singoli ricercatori e distrutture di ricerca. Nella maggior parte dei casi sono strumenti oggettivi in quanto ottenuti da databasededicati costruiti proprio a tal fine.I principali indicatori bibliometrici sono il numero totale di pubblicazioni (P), il numero totale dicitazioni (C) e il numero medio di citazioni per pubblicazione (CPP), l’Impact Factor (ISI-IF), loScimago Impact Factor, l’Immediacy Index, l’Half-life index, l’h-index, il g-index e così via.Ad oggi l’indicatore più diffuso per quantificare il livello della produzione scientifica è l’ImpactFactor, nato da un’intuizione di Eugene Garfiled nel 1958 e al momento di proprietà di ThomsonReuters. L’Impact factor è un indice sintetico che nasce con lo scopo di indicare il peso (fattore diimpatto) di una rivista all’interno del suo settore disciplinare specifico. Matematicamente parlando, è ilrapporto tra il numero complessivo di citazioni ricevute in un dato anno dagli articoli pubblicati da unacerta rivista nei due anni precedenti e il numero di questi ultimi. L’indicatore bibliometrico è poipubblicato a cadenza annuale nel Journal Citation Reports (JCR).Tuttavia, la copertura è volutamente selettiva ed incompleta. Difatti la maggior parte della letteraturascientifica rilevante si concentra in un numero piuttosto limitato di riviste importanti. Inoltre, laselezione delle riviste è svolta a totale discrezione di Thomson Reuters seguendo un approccio qualiquantitativo.Questo significa che nel valutare la produzione scientifica di una struttura, alcuneinformazioni potrebbero essere perse in quanto alcune riviste non sono indicizzate, prese inconsiderazione dal gruppo Thomson Reuters. Per i motivi appena esposti, si è pensato di nonconsiderare solo l’Impact Factor ISI quale indicatore biblimetrico, ma anche quello suggerito dalloScimago Journal Rank Indicator (SJR), da molti considerato il suo più diretto avversario (Falagas etall., 2008; Piazzini, 2010).Il portale Scimago nasce nel 2007 da un gruppo di ricerca del Consejo Superior de InvestigacionesCientíficas (CSIC) dell’Università di Granada, dell’Estremadura, dell’Università Carlos III di Madrid edell’Università Alcalá de Henares (http://www.scimagojr.com/index.php).La base dati utilizzata da Scimago per calcolare il fattore d’impatto delle riviste è Scopus dellaElsevier. Lo Scimago Journal Rank Indicator (SJR) è definito dal gruppo di ricerca come una misurad’impatto, influenza e prestigio, della rivista scientifica, espressa come il numero medio di citazionipesate ricevute nell’anno selezionato da parte dei documenti pubblicati nella rivista, prendendo inconsiderazione i tre anni precedenti. Il peso delle citazioni è dato dall’importanza della rivista in cui la2

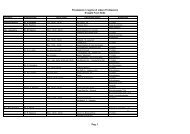

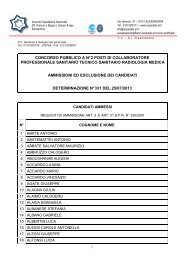

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>citazione è riportata. Questa è la principale differenza tra lo Scimago Journal Rank Indicator (SJR) edil Journal Citation Reports (JCR).Partendo dai citati indicatori bibliometrici, questo lavoro presenta una valutazione dell’attivitàscientifica aziendale ed un successivo ranking delle strutture operative dell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong>. Lametodologia proposta nel ranking è quella classica dell’indicatore bibliometrico (prima sezione), cosìcome quella della Data Envelopment Analysis (seconda sezione).2. Produzione scientifica aziendaleIl Decreto Ministeriale del 28 luglio 2009, art. 3 comma 4 considera l'Impact Factor come uno deiparametri per la valutazione dei titoli presentati in concorsi di ambito scientifico; non solo, questoindicatore bibliometrico viene tenuto in considerazione anche dai singoli istituti di ricerca a caratterenazionale (e.g. IEO, Policlinico San Matteo, etc.). Da qui nasce l’opportunità di valutarequalitativamente, mediante Impact Factor, l’attività di ricerca scientifica svolta dalle strutturedell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> “SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo” di Alessandria.Considerando le strutture operative dell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> di Alessandria, nell’anno 2010 sono statipubblicati 101 articoli scientifici. In base al Journal Citation Reports (JCR) ed al SCImago JournalRank indicator (SJR), la misura complessiva della produzione scientifica aziendale è quantificabilerispettivamente in 341.564 (JCR) e 31.548 (SJR).La tabella 1 presenta l’impact factor medio, rispetto i due indici, delle strutture operative aziendali chehanno pubblicato articoli scientifici nel periodo considerato. Dal confronto tra le due medie è possibilerilevare l’impatto del differente metodo di costruzione dei due indicatori. L’utilizzo del SCImagoJournal Rank indicator (SJR) dà la possibilità di valutare l’impatto di riviste che sono escluse dalgruppo Thomson Reuters. La stessa tabella presenta alcune rilevanti statistiche descrittive calcolaterispetto ai due indici: deviazione standard e numero di articoli pubblicati.Tabella 1Statistiche descrittive degli indicatori bibliometrici per Struttura OperativaJournal Citation Reports (JCR) e SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), 2010Journal Citation Reports(JCR)SCImago Journal Rankindicator (SJR)Struttura Media Std. Dev. Media Std. Dev. Freq.Anatomia Patologica 0.9700 0.3143 0.0953 0.0515 3Anestesia e Rianimazione 13.1900 15.3606 0.8848 1.0152 5Anestesia e Rianimazione Pediatrica 2.4100 0.2418 0.1580 0.0721 2Chirurgia Generale ad Indirizzo Oncologico 2.2250 1.7126 0.1955 0.1450 2Direzione Generale 0.0000 0.0000 0.0240 0.0000 13

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>Ematologia 7.6806 5.1212 1.0009 0.7836 8Endoscopia Digestiva 1.0140 0.0000 0.0930 0.0000 1Fisica Sanitaria 1.6180 0.0000 0.1480 0.0000 1Laboratorio Analisi 1.9095 0.9751 0.1425 0.0417 2Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 2.2460 0.0000 0.1250 0.0000 1Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 2.0732 0.6229 0.1154 0.0347 13Medicina Trasfusionale 2.7373 0.4730 0.1683 0.1496 9Medicina e Chirurgia d’Accettazione 1.9715 0.1556 0.1870 0.0604 4Nefrologia e Dialisi 0.0000 0.0000 0.0270 0.0000 1Neonatologia - Terapia Intensiva 2.9872 1.3641 0.1575 0.0743 11Neurochirurgia 1.4217 0.7951 0.1130 0.0548 3Neurologia 1.5883 0.6638 0.1296 0.0538 7Oculistica 0.9800 0.0000 0.0930 0.0000 1Oncologia 6.9276 5.5333 1.0250 0.7560 8Ortopedia e Traumatologia Pediatrica 0.000 0.0000 0.0450 0.0000 1Pediatria 3.9855 3.5490 0.4550 0.4554 2Psicologia 1.7875 0.6484 0.1110 0.0198 2Radiodiagnostica 1.0140 0.0000 0.0930 0.0000 2Radiologia Interventistica 1.0140 0.0000 0.0930 0.0000 1Radioterapia 1.0140 0.0000 0.0930 0.0000 2Riabilitazione Cardio-Respiratori 1.8717 0.9169 0.1042 0.0510 6Sviluppo Strategico, Innovazione 0.0000 0.0000 0.0240 0.0000 1Terapia del Dolore 1.3290 0.0000 0.0970 0.0000 1Totale 3.3818 4.8279 0.3124 0.5024 101Tabella 2 fornisce l’elenco delle riviste su cui sono stati pubblicati gli articoli scientifici, riportando irelativi fattori d’impatto rispetto ai due indici utilizzati. Il fattore d’impatto medio, nel caso del JournalCitation Reports (JCR) è di 3.3818 mentre, considerando il SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), èpari a 0.3123.Tabella 2Riviste scientifiche ed importanza relativaJournal Citation Reports (JCR) e SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), 2010Rivista JCR SJRActa Neurochirurgica 1.329 0.097Alcohol and Alcoholism 2.599 0.172Annals <strong>of</strong> Oncology 6.452 0.663Blood 10.558 2.238Blood Transfusion 2.519 0.098Breast 2.089 0.212Cancer 5.131 0.746Cancer Research 8.234 1.774Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology 0.000 0.000Clinica Chimica Acta 2.388 0.229Clinical Biochemistry 2.043 0.192Clinical Cancer Research 7.338 1.327Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medic. 2.069 0.192European Journal <strong>of</strong> Physical and Rehabi. 2.246 0.125Epidemiologia e Prevenzione 0.636 0.045Europace 1.839 0.228European Journal <strong>of</strong> Ophthalmology 0.980 0.093European Journal <strong>of</strong> Physical and Rehabi. 2.246 0.125Frontiers in Bioscience (Elite Edition) 4.048 0.1344

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>Frontiers in bioscience (Scholar Edition) 4.048 0.299Giornale Italiano di Nefrologia 0.000 0.027Haematologica 6.532 0.651Headache 2.642 0.238Internal and Emergency Medicine 2.139 0.100International Journal <strong>of</strong> Biological Mark. 1.260 0.148JAMA 30.011 1.996Journal <strong>of</strong> Cellular Biochemistry 3.122 0.522Journal <strong>of</strong> Cellular Physiology 3.986 0.592Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Endocrinology and M. 6.495 0.777Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Oncology 18.970 2.212Journal <strong>of</strong> Endocrinological Investigati. 1.476 0.133Journal <strong>of</strong> Headache and Pain 2.015 0.139Journal <strong>of</strong> Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal 2.071 0.150Journal <strong>of</strong> Orthopaedics and Traumatology 0.000 0.045MR Giornale Italiano di Medicina Riabil. 0.000 0.000Mecosan, Management ed Economia Sanitaria 0.000 0.024Minerva Anestesiologica 2.581 0.107Neurocritical Care 2.353 0.210Neurologia medico-chirurgica 0.677 0.068Neurological Sciences 1.220 0.113Neurosurgical Review 2.259 0.174Pediatric Pulmonology 2.239 0.209Radiologia Medic. 1.618 0.148Surgical Endoscopy 3.436 0.298Transfusion Medicine Reviews 3.881 0.307Tumori 1.014 0.093Prendendo in considerazione le Strutture Operative tabella 3 presenta la distinzione, all’interno dellepubblicazioni su riviste scientifiche, tra articoli originali e abstract di conferenze. In tabella vieneriportato la ripartizione percentuale tra i due tipi di pubblicazione.Tabella 3Abstract e Articoli originali per Struttura Operativa, 2010Struttura Articolo originale AbstractAnatomia Patologica 0.6667 0.3333Anestesia e Rianimazione 0.8000 0.2000Anestesia e Rianimazione Pediatrica 1.0000 0.0000Chirurgia Generale ad Indirizzo Oncologico 0.5000 0.5000Direzione Generale 1.0000 0.0000Ematologia 0.8750 0.1250Endoscopia Digestiva 0.0000 1.0000Fisica Sanitaria 1.0000 0.0000Laboratorio Analisi 0.5000 0.5000Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 2° liv. 0.0000 1.0000Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 3° liv. 0.1538 0.8462Medicina Trasfusionale 0.2222 0.7778Medicina e Chirurgia d’Accettazione 1.0000 0.0000Nefrologia e Dialisi 1.0000 0.0000Neonatologia - Terapia Intensiva Neonat. 1.0000 0.0000Neurochirurgia 1.0000 0.0000Neurologia 0.4285 0.5715Oculistica 1.0000 0.00005

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>Oncologia 0.7500 0.2500Ortopedia e Traumatologia Pediatrica 0.0000 1.0000Pediatria 1.0000 0.0000Psicologia 1.0000 0.0000Radiodiagnostica 0.5000 0.5000Radiologia Interventistica 1.0000 0.0000Radioterapia 1.0000 0.0000Riabilitazione Cardio-Respiratoria 0.1667 0.8333Sviluppo Strategico, Innovazione 1.0000 0.0000Terapia del Dolore 1.0000 0.0000Con la tabella 4 si propone il ranking delle strutture operative dell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> rispetto allamedia delle pubblicazioni scientifiche, considerando esclusivamente gli articoli originali. Le strutturesono ordinate in base al Journal Citation Reports (JCR), prendendo l’ISI Impact Factor qualeindicatore bibliometrico principale e poi, a parità di valore, richiamando lo SCImago Journal Rankindicator (SJR).Tabella 4Ranking Struttura Operativa – Articoli originaliJournal Citation Reports (JCR) e SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), 2010Struttura Media(JCR) Media (SJR)Anestesia e Rianimazione 15.926 1.075Ematologia 7.845 1.051Oncologia 5.906 0.982Pediatria 3.985 0.455Medicina Trasfusionale 3.501 0.414Chirurgia Generale ad Indirizzo Oncologico 3.436 0.298Neonatologia - Terapia Intensiva Neonat. 2.987 0.157Laboratorio Analisi 2.599 0.172Anestesia e Rianimazione Pediatrica 2.410 0.158Medicina e Chirurgia d’Accettazione 1.971 0.187Psicologia 1.787 0.111Fisica Sanitaria 1.618 0.148Neurologia 1.549 0.134Neurochirurgia 1.422 0.113Terapia del Dolore 1.329 0.097Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 3° liv. 1.123 0.062Radiodiagnostica 1.014 0.093Radiologia Interventistica 1.014 0.093Oculistica 0.980 0.093Anatomia Patologica 0.948 0.096Nefrologia e Dialisi 0.000 0.027Direzione Generale 0.000 0.024Sviluppo Strategico, Innovazione 0.000 0.024Riabilitazione Cardio-Respiratoria 0.000 0.000Infine, tabella 5 indica il ranking delle strutture in base al fattore d’impatto complessivo. Anche inquesto caso, l’ordinamento è in base al Journal Citation Reports (JCR), prendendo l’ISI Impact Factorquale indicatore bibliometrico principale e poi, a parità di valore, richiamando lo SCImago Journal6

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>Rank indicator (SJR). Tuttavia, in questa tabella sono considerati sia gli articoli originali sia gliabstract. Considerando le prime tre posizioni, si noti come la scelta dell’indicatore può influenzare ilranking delle strutture.Il totale complessivo coincide esattamente con la misura d’impatto dell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> “SS.Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo” di Alessandria, in base al Journal Citation Reports (JCR) ed alSCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), quantificabile rispettivamente in 341.564 (JCR) e 31.548(SJR).Tabella 5Ranking Struttura OperativaJournal Citation Reports (JCR) e SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), 2010Struttura (JCR) (SJR)Anestesia e Rianimazione 65.950 4.424Ematologia 61.445 8.001Oncologia 55.421 8.200Neonatologia - Terapia Intensiva Neonat. 32.859 1.732Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 3° liv. 26.952 1.450Medicina Trasfusionale 24.636 1.515Riabilitazione Cardio-Respiratoria 11.230 0.625Neurologia 11.118 0.907Pediatria 7.971 0.910Medicina e Chirurgia d’Accettazione 7.886 0.748Anestesia e Rianimazione Pediatrica 4.820 0.316Chirurgia Generale ad Indirizzo Oncologico 4.450 0.391Neurochirurgia 4.265 0.339Laboratorio Analisi 3.819 0.285Psicologia 3.575 0.222Anatomia Patologica 2.910 0.286Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 2° liv. 2.246 0.125Radiodiagnostica 2.028 0.186Radioterapia 2.028 0.186Terapia del Dolore 1.329 0.097Fisica Sanitaria 1.618 0.148Endoscopia Digestiva 1.014 0.093Radiologia Interventistica 1.014 0.093Oculistica 0.980 0.093Ortopedia e Traumatologia Pediatrica 0.000 0.045Nefrologia e Dialisi 0.000 0.027Direzione Generale 0.000 0.024Sviluppo Strategico, Innovazione 0.000 0.024Totale 341.564 31.548Nella sezione successiva il ranking delle strutture sarà normalizzato per l’attività clinica prodotta dallestesse.3. Analisi di efficienza7

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>La metodologia applicata in questo paper è la Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) poiché in grado didare uno score di efficienza ad ogni osservazione (i.e. struttura operativa aziendale), così comesuggerito da Charnes et al. (1978). Nello studio proposto, l’efficienza è stata pensata come l’abilità diogni struttura operativa di massimizzare l’indicatore bibliometrico data l’attività clinica prodotta, cosìcome classificata dalla Regione Piemonte (e.g. ricoveri ordinari, Day-Hospital, attività ambulatoriali,ecc.). 2La metodologia proposta consente di disegnare, risolvendo problemi di ottimizzazione, una frontieraefficiente, cioè una curva o una linea sulla quale vengono collocate le DMU (“Decision MakingUnits”) più efficienti (Charnes et al., 1978; Färe e S. Grosskopf, 1996; Coelli et al., 1998). Quanto piùci si allontana dalla frontiera, tanto più cresce l’inefficienza dell’elemento considerato. L’idea alla basedella costruzione di detta frontiera è di capire quale struttura operativa aziendale abbia unorganizzazione più efficiente rispetto alle altre in termini di produzione scientifica, osservando alcunevariabili (input) come date. L’approccio scelto è output-oriented (Daraio e Simar, 2007; Farrell, 1957):massimizzazione dell’output mantenendo costanti gli input. Le variabili-input considerate nell’analisisono le attività cliniche prodotte dalle strutture estratte dai flussi informativi regionali, mentre comeoutput gli indicatori bibliometrici di cui alla tabella 5 (due distinti indicatori di efficienza).Nel caso analizzato sono stati assunti rendimenti di scala variabili, VRS (Banker et al., 1984), inquanto le strutture operative aziendali studiate non appartengono a una realtà omogenea bensìdifferiscono in base a caratteristiche proprie di ogni specialità medica. È necessario ancorapuntualizzare che il modello qui preso in considerazione è quello proposto da Simar e Wilson (2007) iquali propongono di utilizzare la tecnica del bootstrap per calcolare i DEA-score. Gli score diefficienza calcolati così come è stato illustrato possono assumere valori che vanno da 1 a + infinito edevono essere interpretati nel seguente modo: le osservazioni, cioè le strutture sanitarie aziendali, cheottengono un valore pari all’unità sono efficienti e si situano sulla frontiera, maggiore è il punteggioottenuto (score > 1) e maggiore è l’inefficienza.In tabella 6 viene riportato il ranking delle strutture operative rispetto ai due indici di efficienzaottenuti nella sezione precedente.2 Dato estratto dal database aziendale.8

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>Tabella 6Ranking Struttura Operativa per efficiency scoreJournal Citation Reports (JCR) e SCImago Journal Rank indicator (SJR), 2010Struttura Score(JCR) Score(SJR)Laboratorio Analisi 1.297 1.293Ematologia 1.423 1.800Oncologia 1.493 1.616Anestesia e Rianimazione 1.549 1.626Anestesia e Rianimazione Pediatrica 1.579 1.619Psicologia 1.579 1.623Terapia del Dolore 1.579 1.624Neonatologia - Terapia Intensiva Neonat. 1.582 1.627Radiologia Interventistica 1.591 1.631Medicina Trasfusionale 1.597 1.610Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 3° liv. 1.666 2.107Anatomia Patologica 1.913 1.392Radiodiagnostica 2.698 1.334Radioterapia 2.873 1.474Riabilitazione Cardio-Respiratoria 4.321 4.442Pediatria 5.537 4.110Medicina e Chirurgia d’Accettazione 5.647 4.197Neurologia 7.256 2672.673Neurochirurgia 11.575 13.354Chirurgia Generale ad Indirizzo Oncologico 12.094 33.018Oculistica 15.892 550.045Medicina Fisica e Riabilitazione 2° liv. 23.832 8.917Nefrologia e Dialisi - 8.102Ortopedia e Traumatologia Pediatrica - 15.063Gli score di efficienza sono stati calcolati utilizzando come output i valori di tabella 7 (articolioriginali), considerando sia il Journal Citation Reports (JCR) sia lo SCImago Journal Rank indicator(SJR). Le strutture prive di produzione clinica non sono state considerate (i.e. Direzione Generale eSviluppo Strategico, Innovazione). Inoltre, nel caso dello SCImago index, una trasformazioneesponenziale è stata applicata al fine di rendere tutti i valori maggiori di 1. Le anomalie delle strutturedi Neurologia ed Oculistica sono da ricollegarsi all’indicatore bibliometrico (SJR).4. ConclusioneLa metodologia proposta è in grado di ordinare le strutture operative aziendali (ranking) non solo inbase alla produzione scientifica, sia qualitativa sia quantitativa, ma anche prendendo in considerazionealtri indicatori di performance (produzione clinica aziendale). Pertanto, l’approccio proposto non soloè in grado di normalizzare il dato e rendere comparabile le diverse strutture operative, ma di fornireuno strumento di valutazione su più obiettivi alla Direzione Generale dell’<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong>.La disponibilità di dati su più anni, così come la qualità degli stessi (e.g. complessità dei caso clinico),darà la possibilità agli autori di perfezionare l’analisi proposta. Adottando l’approccio Two-stage di9

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 1/<strong>2012</strong>Simar e Wilson (2007), si potrà indagare sia le variabili che influenzano gli score di efficienza sial’impatto degli score sulla qualità percepita (analisi di customer satisfaction).BibliografiaBanker R.D., Charnes A., Cooper W.W. (1984), Some Models for Estimating Technical and ScaleInefficiencies in Data Envelopment Analysis. Management Science, 30(9): 1078-1092.Charnes A., Cooper W.W., Rhodes E. (1978), Measuring the Efficiency <strong>of</strong> Decision Making Units.European Journal <strong>of</strong> Operational Research, 2: 429-444.Coelli T., Rao Prasada D.S., Battese G.E. (1998), An Introduction to Efficiency and ProductivityAnalysis, Noerwell, Kluwer Academic Publishers.Daraio C., L. Simar (2007), Advanced Robust and Nonparametric Methods in Efficiency Analysis:Methodology and Application, Berlin, Springer.Falagas M.E., Kouranos V.D., Arencibia-Jorge R., Karageorgopoulos D.E. (2008), Comparison <strong>of</strong>SCImago journal rank indicator with journal impact factor, «The FASEB Journal, 22(August): 2623-2628.Färe R. e S. Grosskopf (1996), Intertemporal Production Frontiers: With Dynamic DEA, BostonKluwer Academic Publishers.Farrell M. J. (1957), The Measurement <strong>of</strong> Productive Efficiency. Journal <strong>of</strong> the Royal StatisticalSociety, 120(3): 253-290.Piazzini T. (2010), Gli indicatori bibliometrici. JLIS.it, 1(1): 63–86; DOI: 10.4403/jlis.it-24.Simar L., Wilson P.W. (2007), Estimation and inference in two-stage, semi-parametric models <strong>of</strong>production processes. Journal <strong>of</strong> Econometrics, 136: 31-64.10

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>Titolo: “SPDC a porte aperte”: elaborazione di un processo – utilizzando la metodologia FMEA –riguardante le uscite dal reparto da parte di pazienti affetti da malattia mentaleAutori: Barbera V., Catarisano M., Cavarra S., Crisci L., Podestà P., Pomillo G., Prelati M.,Piantato E.*; 1Tipo: Articolo originaleJEL code: I100 - <strong>Health</strong>: GeneralKeywords: Failure Mode Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMEA);AbstractObiettivi: il progetto si propone di elaborare un processo lavorativo critico “uscita del paziente” alfine di un miglioramento continuo della qualità delle prestazioni <strong>of</strong>ferte dalla StrutturaComplessa uniformando, sotto quest’aspetto, il paziente con disturbi mentali a tutti gli altridegenti ospedalieri;Metodologia: gruppo di lavoro formato dall’equipe medica e infermieristica, avvalendosi dellametodologia FMEA;Risultati: l’elaborazione di una scheda FMEA con l’analisi del processo “uscita pazienti”;Conclusioni: Il documento prodotto ha suscitato nel gruppo di lavoro notevoli discussioni eriflessioni sull’operato di ciascuno; l’elaborato finale ha visto numerose revisioni ad1 S.O.C. PSICHIATRIAA.O. “SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo” di AlessandriaTel: 0131/206111* Autore per la corrispondenzaE-mail: epiantato@ospedale.al.it;1

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>ogni incontro di lavoro e particolarmente utile sarebbe stato includere nel gruppo unfacilitatore esterno con esperienza metodologica in merito.1. IntroduzioneNell’ambito di una Psichiatria più moderna si è sviluppato il concetto di reparto “a porte aperte”affinché venisse meno l’aspetto reclusivo connesso con i reparti per malati mentali, soprattuttoquando questi erano locati all’interno di ospedali generali.Alla luce di questa breve premessa le equipe medica e infermieristica hanno formato un gruppo dilavoro con lo scopo di elaborare – avvalendosi della metodologia FMEA – un processo lavorativocritico “uscita del paziente”: questo nell’ottica di un miglioramento continuo della qualità delleprestazioni <strong>of</strong>ferte dalla SC uniformando sotto questo aspetto il paziente con disturbi mentali a tuttigli altri degenti ospedalieri.Considerando che “l’uscita del paziente dal reparto” non pianificata poteva potenzialmente averegravi ricadute sul paziente in tema di sicurezza e sugli operatori sanitari legati alla responsabilità, siè ritenuto opportuno fare un’analisi del processo e pianificarne gli interventi contenitivi rispetto airischio che tale procedura poteva comportare.Si è provveduto ad identificare un gruppo di lavoro così composto: il Direttore della S.O.C., Dr. E. Piantato il responsabile del Rischio Clinico di Struttura, Dr. M. Prelati la Coordinatrice Infermieristica, V. Barbera gli Infermieri Catarisano M., Cavarra S., Crisci L., Podestà P. e Pomillo G.2. Pianificazione del progettoNella riunione preliminare del gruppo di lavoro si è proceduto alla definizione del materiale e dellametodologia da utilizzare; definizione del crono programma e la calendarizzazione degli incontri.In merito alla ricerca bibliografica, il gruppo di lavoro si è orientato sulle principali Banche Datiinternazionali (Medline, Cochrane), ricerca libera su Google e fonti cartacee (testi di Psichiatria perla parte riguardante le Scale di Valutazione in ambito psichiatrico). Sostanzialmente la ricercabibliografica non ha sortito risultati in merito alla gestione del rischio clinico con la metodologia delFailure Mode Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMEA) in ambito psichiatrico e nello specificosull’applicazione della stessa sul processo “Uscite dei pazienti”.Le principali applicazioni di questa metodologia riguardavano l’ambito laboratoristico,cardiologico, rianimatorio, ortopedico e oncologico ed erano strettamente correlate a2

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>manovre/operazioni con un elevato livello di tecnicità sia preparatoria sia esecutiva. La raccolta edistribuzione della documentazione riguardante la Metodologia FMEA è stata eseguita da appositoincontro formativo del gruppo di lavoro in merito alla stessa (Barbera - Piantato).Il gruppo di lavoro ha iniziato a riunirsi nel settembre 2010 (superato il periodo di ferie deicomponenti) con cadenza settimanale/quindicinale in relazione agli impegni degli operatori.Nella tabella che segue, è definito il crono programma concordato dal gruppo di lavoro.Tabella 1Programma di lavoroAttività Giugno Settembre Ottobre Novembre DicembreIdentificazione del processo“Uscita paziente”xAnalisi del processo secondo lametodologia FMEAxxPianificazione del processo edefinizione dell’Indice di Prioritàdi RischioxxConclusione progettox3. Come veniva gestita “l’uscita pazienti”Nel corso degli ultimi due anni si ritenuto opportuno migliorare/umanizzare la degenza presso laS.O.C. Psichiatria-SPDC in particolar modo dando l’opportunità ai degenti ricoverati in regimevolontario di poter uscire dal reparto da soli o accompagnati da operatori e/o famigliari se lecondizioni psicopatologiche non ostavano.L’uscita era programmata al mattino durante il “briefing” quotidiano nel quale medici e infermieridiscutevano delle condizioni dell’utente, era redatta una scheda con indicati gli orari di uscita e lemodalità (accompagnato o meno). La scheda concordata era appesa fuori dalla porta dellamedicazione, ai degenti era illustrato l’iter procedurale.Si era concordato tra medici e infermieri che il primo giorno di ricovero al pazientecautelativamente non era permesso di uscire per valutarne, durante la giornata, le condizionicliniche e il grado di aderenza alle regole definite.Nel corso di questi due anni si sono verificati diversi eventi avversi, tra i quali: allontanamento delpaziente, crisi di ansia, ipotensione e discomportamentismi. Alla luce di questi eventi avversi che si3

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>sono verificati, si è ritenuto opportuno migliorare e perfezionare il processo per cercare di conteneregli stessi applicando al processo una tecnica di gestione proattiva del rischio clinico: la metodologiaFMEA.4. Il rischio clinicoIl rischio clinico è la probabilità che un paziente sia vittima di un evento avverso, cioè subisca “unqualsiasi danno o disagio imputabile, anche se in modo involontario, alle cure mediche prestatedurante il periodo di degenza, che causa un prolungamento del periodo di degenza, unpeggioramento delle condizioni di salute o la morte (Kohn, IOM 1999)Il rischio clinico può essere arginato con iniziative di Risk Management messe in atto a livello disingola struttura sanitaria, a livello aziendale, regionale, nazionale. Queste iniziative devonoprevedere strategie di lavoro che includano la partecipazione di numerose figure che operano inambito sanitario.La sicurezza del paziente pertanto, deriva, quindi dalla capacità di progettare e gestireorganizzazioni in grado sia di ridurre la probabilità che occorrano gli errori (prevenzione) sia direcuperare e contenere gli effetti degli errori che comunque avvengono (protezione).La metodologia di cui è possibile disporre si avvale di due tipologie d’analisi: un’analisi di tiporeattivo e una di tipo proattivo. L’analisi reattiva prevede uno studio a posteriori degli incidenti ed èmirata a individuare le cause che hanno permesso il loro verificarsi. L’analisi proattiva, invece,mira all’individuazione ed eliminazione delle criticità del sistema prima che l’incidente occorra ed èbasata sull’analisi dei processi che costituiscono l’attività, ne individua i punti critici con l’obiettivodi progettare sistemi sicuri (Reason et al., 2001; Reason, 2002).Tabella 2Strumenti di gestione del rischio clinico reattivi e proattiviReattiviIncident ReportingRoot Cause AnalysisUtilizzo dei dati amministrativi e informativiRewiewIndiziProattiviFMEA/FMECANel caso specifico agli operatori della SOC Psichiatria è stato dato mandato di utilizzare lametodologia FMEA al processo clinico/assistenziale prescelto per cercare di contenere/ridurre ilrischio clinico ad esso correlato pertanto, nella prossima sezione verranno brevemente illustrate lecaratteristiche di tale tecnica.4

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>5. L’analisi proattiva del rischio clinicoAlla base delle metodologie d’analisi proattive risiede l’idea che sia possibile prevenire gli errori.Infatti, tutte le metodologie d’analisi di tipo proattivo, che si possono condurre sia con indagini ditipo qualitativo che quantitativo, vanno ad analizzare il processo nelle sue fasi, al fine di individuarele criticità di sistema e i possibili ambiti di errore umano, per porvi un tempestivo rimedio.Il processo è scomposto in macroattività a loro volta analizzate secondo tutti i singoli compiti chedevono essere portati a termine affinché l’attività sia conclusa con successo. Per ogni singolocompito si cercano di individuare gli errori che si possono verificare durante l’esecuzione e lecosiddette modalità di errore che vengono valutate quantitativamente al fine di identificare il rischioassociato ad ognuna.5.1 Valutazione del rischioIl rischio esprime non solo la probabilità di occorrenza di un errore, ma anche il possibile danno peril paziente.Il rischio (R) rappresenta la misura della potenzialità di danno di un generico evento pericoloso eviene prodotto come espresso della probabilità di accadimento dell’evento (P) per la gravità deldanno associato (D):R = P x DLa stima del livello di rischio può essere realizzata in termini quantitativi attraverso datiprobabilistici sia di occorrenza dell’errore sia del danno conseguente, e qualitativi, sfruttandol’esperienza e il giudizio del personale ospedaliero.La valutazione del rischio può essere condotta a diversi gradi di complessità (Trucco et al., 2003).Al crescere del livello di dettaglio con cui sono analizzati i processi organizzativi e passando dametodi di valutazione qualitativi a metodi quantitativi, s’incrementa la rilevanza dei risultati ottenutied anche il loro valore informativo. Ciò comporta, però, anche una crescita della complessità diapplicazione dei metodi e le risorse di tempo e personale richiesto.5.2 Analisi proattiva del rischio clinico con metodologia FMEA/FMECAL’acronimo FMEA/FMECA tradotto come analisi critica dei modi di guasto/errore e dei loro effetti,si tratta di una metodologia di analisi degli errori qualitativa e quantitativa. Si tratta di una tecnicaprevisionale utilizzata da oltre 40 anni negli USA in campo missilistico e dell’elettronica, e dadiversi anni ha trovato applicazione anche in ambito sanitario per la gestione del rischio clinico.5

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>Prevede considerazioni preventive dei possibili guasti/errori che portano alla valutazione obiettivadel progetto e delle alternative, alla previsione di prove e controlli e infine alla esplicitazione di unriferimento con cui confrontare il “vero” prodotto della nostra realtà.Le fasi della metodologia FMEA:1. Analisi delle fasi del processo2. Identificazione delle funzioni/attività3. Identificazione delle modalità di errore4. Determinazione dell’indice di Priorità di Rischio (IPR)5. Identificazione delle possibili cause6. Individuazione delle azioni correttive7. Applicazione delle azioni correttive8. Valutazione dell’IPR dopo revisione delle criticità5.3 L’analisi dei rischiLa definizione dell’Indice di Rischio Clinico (IRC) è considerata valutando le diverse variabili:IRC = Gravità x Probabilità x Rilevabilitàdove Gravità è la valutazione quantitativa del danno che potrebbe derivare al paziente nel caso diaccadimento dell’evento avverso; Probabilità è la misura della probabilità di accadimentodell’evento avverso; Rilevabilità è la valutazione delle possibilità dell’organizzazione per rilevarel’evento ed evitarne le conseguenze.Per quanto riguarda la FMEA, l’analisi dei rischi è legata all’errata valutazione del paziente (i.e.valutazione della gravità), così come mostrato nelle tabelle successive. In tabella 3 è proposta lavalutazione della gravità legata all’errata valutazione del paziente mentre in tabella 4 la rilevabilitàdell’evento.Tabella 3Analisi dei rischi: valutazione della gravità legata all’errata valutazione del pazienteGRAVITA’Punteggio Descrizione Note di valutazione1 Nessun dannoL’evento non ha comportato alcun danno oppure ha comportatosoltanto un maggior monitoraggio del paziente;6

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>2 Danno lieve3 Danno medio4 Danno graveDiscomportamentismi (Causa debiti al bar, chiede soldi, sigarette);Irritazione del paziente con intemperanze verbali;Richiesta di dimissione del paz. In caso di diniego permesso uscita;episodi ipotensivi;Crisi di ansia;L’evento ha causato un prolungamento della degenza in seguito ad unpeggioramento delle condizioni cliniche;Passaggio a ricovero in regime di TSO;Si procura lesioni temporanee;Importuna persone all’esterno;Si procura oggetti per l’autolesionismo o accendini vietati in reparto;Fuga del paziente;Trauma accidentale in seguito a tentativo di fuga;Aggredisce persone;Si procura sostanze d’abuso; alcolici e/o droghe;5 Morte Suicidio del paziente;Tabella 4Analisi dei rischi: rilevabilità dell’eventoRILEVABILITA’Punteggio Descrizione Note di valutazione12Altissima(errore sempre rilevato)Alta(errore probabilmente rilevato)Si rileva 9 volte su 10 che l’evento accadaSi rileva 7 volte su 10 che l’evento accada3Media(probabilità moderata di rilevazionedell’errore)Si rileva 5 volte su 10 che l’evento accada4Bassa(probabilità bassa di rilevazione dell’errore)Si rileva 2 volte su 10 che l’evento accada5Remota(rilevazione praticamente impossibile)Si rileva 0 volte su 10 che l’evento accadaIn tabella 5 si propone la valutazione della probabilità di accadimento dell’evento avverso.7

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>Tabella 5Analisi dei rischi: valutazione della probabilità di accadimento dell’evento avversoPROBABILITA’Punteggio Descrizione Note di valutazione1REMOTA(non esistono eventi noti)Si può verificare 1 caso su 5002345BASSA(possibile ma non esistono dati noti)MODERATA(documentata ma infrequente)ALTA(documentata e frequente)MOLTO ALTA(documentata quasi certa)Si può verificare 1 caso su 250Si può verificare 1 caso su 50Si può verificare 1 caso su 25Si può verificare 1 caso su 5Quanto proposto nella tabella successiva è la scheda FMEA con l’analisi del processo “uscitapazienti” elaborata dal gruppo di lavoro. Nella tabella 6 è invece proposto l’indice di priorità dirischio.8

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>Descrizione del processo Descrizione dell’errore Effetti dell’erroreN. rif Processo Attività Modalità CauseProbabilitàRilevabilitàGravitàIPR Misure per la riduzione del rischio NoteA1Programmazioneuscita pazienti1) Errore di valutazione;2) Errore di trascrizione;3) Non compilazione dellascheda;1) Numerosità dei paz2) Non presa visione dellescale di Valutazione3) urgenze di reparto1)Discomportamentismi;sentimenti di rabbia delpaziente;2)richiesta di dimissione delpaz.in caso di negatopermesso3)Fuga paz.2__2__1__1__1__1__3__2__1__1__4__5__3__2__2__1__1__1__18_8__2__1__4__5__1) Definizione di una Procedura “uscita paz.Dal reparto”;2)Adozione di scale di valutazione;3) Discussione casi durante briefingmattutino;4) Visione rapporto gg prec.;5) Valutazione al letto del pz.Uscitapazienti4) Omissione paziente nellascheda uscita pazienti;5) Omonimia di pz;6) Paz. In TSO.4) Assenza di una“procedura” chestandardizzi le modalità diprogrammazione;4) Fuga di paz. In TSO;6)istruire i pazienti sulle modalità di uscitadal reparto.7) Stilare una ProceduraUscita paz. dal reparto;8) Aggiungere nel “Foglio Notizie reparto”le modalità di uscita dal reparto.A2Uscita dei pazientiAccompagnati dagliInfermieri1) Distrazione degli Infermieri;2) Non attinenza agli orari diuscita;1)Insuff. Numero dioperatori;2)Difficoltà programmarepiù turni di uscita;3)incompatibilità trapazienti;1) Fuga del paziente;2) Fuga di pazienti in TSO;3) Procurarsi accendinivietati in reparto;2___14___13___124___11) Definizione del rapportopazienti/operatori;Istituzione delregistroUscitePazienti;4)Non osservanza dellascheda Uscite Pazienti daparte dell’operatore;5) Uscita di paz. Nonautorizzati4) Aggressione a persone;5) Procurarsi oggetti perautolesionismi;2) Definizione di criteri di sorveglianza peroperatori;10

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>Tabella 6Indice di Priorità di RischioA 1 ; 1 = IPR 18Errore di valutazioneA 1 ; 2 = IPR 8Errore di trascrizioneA 1 ; 3 = IPR 2Non compilazione scheda uscita pazientiA 1 ;4 = IPR 1Omissione di paziente nella scheda “Uscite pazienti”A 1 ;5 = IPR 5Omonimia di pazienteA 1 ; 6 = IPR 5Paziente in trattamento sanitario obbligatorioA 2 ; 1 = IPR 24Distrazione degli infermieriA 2 ; 2 = IPR 1Non attinenza agli orari di uscita predefinitiL’analisi del processo con la scheda FMEA ha evidenziato la necessità di creare alcuni strumenti di“controllo” sulla gestione del processo “Uscite pazienti” aventi la funzione di uniformare ilcomportamento degli operatori sanitari e di monitoraggio del sistema.Allo stato attuale non esistevano dati storici cui far riferimento per cui il calcolo degli indici di priorità edil rischio è unicamente basato sulla percezione collettiva del gruppo di lavoro in base alla propriaesperienza lavorativa.6. ConclusioniIl documento prodotto ha suscitato nel gruppo di lavoro notevoli discussioni e riflessioni sull’operato diciascuno; l’elaborato finale ha visto numerose revisioni ad ogni incontro di lavoro e particolarmente utilesarebbe stato includere nel gruppo un facilitatore esterno con esperienza metodologica in merito.La difficoltà maggiore è derivata dal fatto che il processo preso in analisi è particolarmente ricco divariabili umane comportamentali legate sia al paziente sia all’operatore ed essendo un processo pocotecnici stico, non a caso, tale metodologi vede la sua frequente applicazione laddove i processi lavorativisono molto tecnicizzati (es. laboratorio analisi, procedure chirurgiche, somministrazioni di terapie, ecc).Sono stati allegati al presente lavoro i documenti ex-novo elaborati derivanti dall’analisi del processo acompletamento del lavoro.11

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 2/<strong>2012</strong>BibliografiaInstitute <strong>of</strong> Medicine (IOM). To Err is Human: Building a Safer <strong>Health</strong> System. LT Kohn, JM Corrigan,MS Donaldson, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, (1999).Reason J. (2002). Combating omission errors through task analisys and good reminders. Qual Saf <strong>Health</strong>Care, 11:40–44.Reason JT, Carthey J, de Leval MR. (2001). Diagnosis <strong>of</strong> “vulnerable system syndrome”: an essentialprerequisite to effective Risk management. Qual <strong>Health</strong> Care,10(suppl II): 21–5.Trucco P., Cavallin M., Bonini P.A., Bubboli F. (2003), “Valutazione del rischio organizzativo neiprocessi di cura”, RischioSanità, ASSINews, Vol.11, pp. 26-32, Dicembre.Ministero della Salute – Dipartimento della Qualità Risk management in sanità – Il problema degli errori,Commissione Tecnica sul Rischio Clinico (D.M. 5 marzo 2003), Roma, marzo 2004.Regione Emilia Romagna: FMEA-FMECA Analisi dei modi di errore/guasto e dei loro effetti nelleorganizzazioni sanitarie, Dossier n. 75, Agenzia Sanitaria Regionale dell’Emilia Romagna, Bologna,novembre 2002.Elenco documenti allegati:- Nota informativa per i pazienti- Registro “uscita pazienti”- Rapporto Uscite pazienti- Registro degli eventi avversi- Overt Aggression Scale12

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> NazionaleSS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare ArrigoAlessandriaVia Venezia, 16 – 15100 ALESSANDRIATel . 0131 206111 – www.ospedale.al.itinfo@ospedale.al.itC.F. – P.I. 01640560064SOC PSICHIATRIADirettore Dr. E. PiantatoMODALITA' USCITA DEI PAZIENTI FUORI DAL REPARTOI pazienti, durante il periodo di degenza presso il nostro reparto, potranno usufruire dipermessi di uscita dal reparto (di breve durata) previa autorizzazione da parte del medico.Quotidianamente verrà compilata una scheda posta fuori dalla sala di medicazione, doveverranno elencati i pazienti che autorizzati ad uscire dal reparto, indicando la modalità diuscita, ovvero, definendo se un paziente potrà uscire dal reparto da solo, o accompagnato(da un infermiere o un familiare), rispettando gli orari di uscita definiti dal reparto.La scheda verrà quotidianamente aggiornata e affissa sulla porta dello studio"INFERMIERI".I pazienti ricoverati in regime T.S.O.(trattamento sanitario obbligatorio), nonpossono uscire dal reparto.Orari uscita dei pazienti:Dalle ore …. alle ore ….Dalle ore …. Alle ore ….Dalle ore …. Alle ore ….Il primo giorno di ricovero non è permesso uscire.Non è permesso durante tali uscite dal reparto recarsi fuori dall’ospedale.

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> NazionaleSS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare ArrigoAlessandriaVia Venezia, 16 – 15100 ALESSANDRIATel . 0131 206111 – www.ospedale.al.itinfo@ospedale.al.itC.F. – P.I. 01640560064SOC PSICHIATRIADirettore Dr. Ennio PiantatoData _________________Cognome e Nomedel pazienteEsceoreRientraoreSoloAccompagnatodafamiliariAccompagnatodaInfermierifirmaInf.Eventi avversi dasegnalare

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> NazionaleSS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare ArrigoAlessandriaVia Venezia, 16 – 15100 ALESSANDRIATel . 0131 206111 – www.ospedale.al.itinfo@ospedale.al.itC.F. – P.I. 01640560064I PAZIENTI IN TRATTAMENTO SANITARIO OBBLIGATORIO NON POSSONOUSCIRE DAL REPARTOSOC PSICHIATRIADirettore Dr. E. PiantatoRapporto uscita pazientiCognome:Nome:Tiene un comportamento adeguato si noChiede soldi o sigarette si noSi procura debiti al bar si noImportuna persone all’esterno si noCerca di allontanarsi dal gruppo si noLamenta crisi d’ansia si noPresenta episodi ipotensivi si noManifesta intemperanze verbali si noSi procura lesioni accidentalmente si noSi procura lesioni volontariamente si noAggredisce persone si noElude la sorveglianza e fugge si noDecesso si no

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> NazionaleSS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare ArrigoAlessandriaVia Venezia, 16 – 15100 ALESSANDRIATel . 0131 206111 – www.ospedale.al.itinfo@ospedale.al.itC.F. – P.I. 01640560064SOC PSICHIATRIADirettore Dr. E. PiantatoCognome Nome Data ora Numero progressivoEntità danno: Lieve medio graveDescrizione dell’evento avversoFirma infermiere:

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> NazionaleSS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare ArrigoAlessandriaVia Venezia, 16 – 15100 ALESSANDRIATel . 0131 206111 – www.ospedale.al.itinfo@ospedale.al.itC.F. – P.I. 01640560064OVERT AGGRESSION SCALEOAS - #755Cognome e Nome………………………………………………Data dinascita……….….………….Codice Paziente…………….…….Valutazione………………..Datavalutazione…………..……….TURNO: 0) NOTTE 0) GIORNO 0)SERA0) Segnare qui se durante il turno non si sono verificati comportamenti aggressivi(verbali o fisici) contro se stesso, gli altri o gli oggetti.Comportamento aggressivo (segnare tutto ciò che è pertinente)Aggressività verbaleAggressività fisica autodiretta0) Fa grandi schiamazzi, grida inmodo irato0) Grida insulti personali lievi (peres., “Sei stupido!”)0) Impreca in maniera rabbiosa,nella rabbia usa un linguaggioosceno, fa minacce nonparticolarmente serie verso glialtri o se stesso0) Fa serie minacce di violenzaverso glialtri (“Ti uccido!”), o chiede diessere aiutato a controllarsiAggressività fisica contro gli oggetti0) Sbatte la porta, butta all’aria ivestiti, crea disordine0) Getta a terra gli oggetti, prende acalci i mobili senza romperli,0) Si gratta o si graffia, si picchia, sistrappa i capelli (senza o solo conminime lesioni)0) Sbatte la testa, colpisce gli oggetticon i pugni, si butta per terra ocontro gli oggetti (si ferisce senzagravi danni)0) Piccoli tagli o ammaccature, lievibruciature0) Si provoca mutilazioni, si fa taglipr<strong>of</strong>ondi, si morde a sangue, siprovoca danni interni, fratture,perdita di coscienza, perdita didentiAggressività fisica contro le altrepersone0) Fa gesti minacciosi, agita i pugniverso gli altri, agguanta gli alti peri vestiti0) Percuote, tira calci, spintona, tira i

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> NazionaleSS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare ArrigoAlessandriaVia Venezia, 16 – 15100 ALESSANDRIATel . 0131 206111 – www.ospedale.al.itinfo@ospedale.al.itC.F. – P.I. 01640560064sporca il muroRompe gli oggetti, manda infrantumi le finestrecapelli (senza fare danni)0) Aggredisce gli altri provocandoloro danni fisici moderato/lievi(ammaccature, distorsioni, lividi)0) Aggredisce gli altri causando lorogravi danni fisici (fratture, feritepr<strong>of</strong>onde, lesioni interne)L’episodio è iniziato alle ore(h/min)ed è duratoINTERVENTI (segnare tutto ciò che è pertinente)0) Nessuno0) Parlato con ifamiliari0) Stretta sorveglianza0) Tenere fermo ilpaziente0) Terapia mmediataper os0) Terapia immediataim/iv0) Separazione senzaRinchiudere il p.(durata)0) Uso di contenzione0) Le lesioni richiedonouna terapiaimmediata per il p.Le lesioni richiedonouna terapiaimmediata per altrepersone

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong>Title: The Impact <strong>of</strong> Presumed Consent Law on Organ Donation: An Empirical Analysisfrom Quantile Regression for Longitudinal DataAuthors: Giácomo Balbinotto Neto 1* ; Everton Nunes da Silva 2 ; Ana Katarina Campelo 3 ;Type: Original Article;Keywords: presumed consent; organ donation; quantile regression for panel data;AbstractHuman organs for transplantation are extremely valuable goods and their shortage is aproblem that has been verified in most countries around the world, generating a longwaiting list for organ transplants. This is one <strong>of</strong> the most pressing health policy issues forgovernments. To deal with this problem, some researchers have suggested a change inorgan donation law, from informed consent to presumed consent. However, fewempirical works have been done to measure the relationship between presumed consentand the number <strong>of</strong> organ donations. The aim <strong>of</strong> this paper is to estimate that impact, usinga new method proposed by Koenker (2004): quantile regression for longitudinal data, fora panel <strong>of</strong> 34 countries in the period 1998-2002. The results suggest that presumedconsent has a positive effect on organ donation, which varies in the interval 21-26% forthe quartiles {0.25; 0.5; 0.75}, the impact being stronger in the left tail <strong>of</strong> the distribution.1 Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Law and Economics UFRGS/PPGE and PPGDir/UFRGS – Brazil;* Corresponding author, E-mail: giacomo.balbinotto@ufrgs.br;2 PhD Economics – UFRGS/PPGE, Ministério da Saúde, Brazil;3 Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Economics – UFPE/PIMES – Brazil;1

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong><strong>Health</strong> expenditure has an important role on the response variable as well, the coefficientestimate varying between 42-52%.1. IntroductionThe demand for organ transplants is large and has been increasing over time, and theshortage <strong>of</strong> human organs is a pressing issue to policy makers and governments. Thisissue has motivated researchers to study the determinants <strong>of</strong> organ donation rates and themagnitude <strong>of</strong> their impact on the supply <strong>of</strong> organs.A particular debate has arisen in this context: the matter <strong>of</strong> legislative default oncadaveric organ donation. Following this debate, some researchers have investigated therelationship between the type <strong>of</strong> legislation on organ donation and the number <strong>of</strong>available cadaveric organs for transplantation, mainly after the successful experiences <strong>of</strong>Spain, Austria, Italy and Belgium, which have adopted presumed consent law for organdonation 4 . Under presumed consent law, all deceased people are considered potentialdonors in the absence <strong>of</strong> explicit opposition when alive to donation. However, underinformed consent law, the donors must give formal agreement to potentially becomingdonors before they die.As it has been stressed by some authors (Fevrier and Gay (2004) and Gill (2004), forexample), neither presumed consent nor informed consent respects the will <strong>of</strong> populationas a whole, particularly for people that do not register their will 5 . On the one hand,defenders <strong>of</strong> presumed consent have argued that there are more donations when presumedconsent takes place. On the other hand, opponents <strong>of</strong> presumed consent have pointed outthat this system is neither morally nor ethically acceptable. In fact, the huge majority <strong>of</strong>4 Gundle (2004), Gnant et al. (1991), Michielsen et al. (1996), Matesanz and Miranda (2001), Kaur (1998)and Kennedy et al. (1998).5 Following Gill (2004): “no matter how well the current system (informed consent) is instituted, there willstill be cases in which people who would have preferred to donate their organs will be buried with all theirorgans intact; call these mistaken non-removals. And no matter how well presumed consent is instituted,there will still be some cases in which people who would have preferred to be buried with all their organsintact will have some <strong>of</strong> organs removed, call these mistaken removals.”2

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong>countries that have presumed consent in practice allow the family to make the finaldecision about donation, which weakens the argument <strong>of</strong> the informed consent defenders.Healy (2005) argued that the advantage in “having a presumed consent law might mean,in effect, that the question put to donor families is assumed to be something like ‘do youhave any reason to think the donor would have objected?’ rather than something like ‘canwe have your permission to go ahead?’” It is easier to get the family’s agreement todonate the organs <strong>of</strong> a loved one, since the collective expectation is to become a donorunder presumed consent law. However, under an informed consent law, the family musttake a special decision, since the default is not to donate the organs <strong>of</strong> a loved one. Thereis ample discussion about this topic, both in medical and political communities and ininternational health organizations. Recently the UK parliament held a debate about thepossibility <strong>of</strong> implementing presumed consent in Britain. Argentina, in 2005 changed itslaw on organ donation to presumed consent. After three years <strong>of</strong> presumed consent lawexperience, Brazil 6 returned to informed consent in 2001.Despite the importance <strong>of</strong> this matter, few studies focus on measuring the relationshipbetween presumed consent and cadaveric organ donation. A multivariate model isrequired to analyze this relationship in order to control some observed heterogeneity,such as income, religious belief, type <strong>of</strong> legal system, besides others specifically relatedto organ donation, such as potential donors (from traffic accidents and celebro-vasculardisease). Abadie and Gay (2004) and Healy (2005) found a positive relationship betweenpresumed consent and cadaveric organ donation. However, they had just used OECDcountries 7 . Our paper has the advantage <strong>of</strong> analyzing a large sample, which also includesLatin countries and other countries with low cadaveric organ donation. Furthermore, wecan verify whether the positive relationship between presumed consent and organdonation holds good when we analyze a more heterogeneous sample <strong>of</strong> countries.In order to proceed with the analysis, we have applied a new method developed byKoenker (2004): quantile regression for panel data. This method combines the panel dataapproach with a focus upon estimation <strong>of</strong> effects on the quantiles <strong>of</strong> the response variable6 The Brazilian case will be discussed in more detail in section 3.1.7 Their sample sizes were 22 and 17 countries, respectively.3

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong>distribution. This technique works better with outliers present. Notably, our sample hassome outliers, such as Spain 8 , well known in the literature as the most efficient model <strong>of</strong>organ procurement.The main goal <strong>of</strong> this article is to analyze the impact <strong>of</strong> presumed consent on organdonation rates, using a quantile regression for panel data approach with a sample <strong>of</strong> 34national states over 5 years (1998-2002). This paper follows the model proposed byAbadie and Gay (2004). Following this introduction, section II discusses the organshortage problem; section III describes the data and method applied; the main empiricalresults are given in section IV and the conclusions in Section V.2. The Organ Shortage ProblemThe first successful kidney transplant took place in 1954 (Boston - USA), and manyimprovements have been made since that event. Nowadays, kidney transplants havebecome the most cost-effective treatment for people suffering end-stage renal disease(ESRD) 9 . That means a longer life and better quality <strong>of</strong> life for patients, and an efficientway to spend health resources. However, for some terminal diseases (heart, lung, liverand pancreas) transplant is the only way to keep a patient alive, once there is no substitutetreatment 10 .In 2005, more than 28,000 transplants had been carried out in the USA, an increase <strong>of</strong>around 20% relative to 2000 (UNOS, 2006). Brazil had undertaken 14,740 transplants in2004, an increase <strong>of</strong> 30% relative to 2002 (MS, 2006). In Australia, 649 transplants wereperformed in 2004, an increase <strong>of</strong> 20% compared to 2003 (ANZOD, 2006). These8 Abadie and Gay (2004) and Healy (2005) have run their models including and excluding Spain. Themodel without Spain fitted better than otherwise. Methods based on conditional mean, as the case <strong>of</strong> theseauthors (panel data), are especially affected by outliers. Quantile regression is robust to outliers (Koenkerand Basset, 1978).9 Garner and Dardis (1987), Karlberg (1992), Karlberg and Nyberg (1995), Evans (1986), Roberts et al.(1980), Schersten et al. (1986), Kasiske (1998), Campbell and Campbell (1978) and Evans and Kitzmann(1998).10 This explains the reason why waiting lists are shorter for heart, lung, liver and pancreas transplantation;because many people die before getting a transplant. This is not the case with ESRD patients, since dialysiscan replace the kidney functions.4

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong>transplantation rates could be higher still except that there is a serious constraint: theorgan donation shortage. The supply <strong>of</strong> organs is smaller than required to keep up withthe demand. Due to this gap, the waiting list for a transplant has increased in mostcountries around the world. Several factors may have caused increase in the demand fororgan transplantation. First, many improvements have been made on immunosuppressivedrugs, especially after the use <strong>of</strong> cyclosporine in the 1980’s, which have tremendouslyimproved graft survival in all types <strong>of</strong> transplantation. Second, there has been an increasein the number <strong>of</strong> surgeons and physicians with specialized knowledge, improvingmedical awareness <strong>of</strong> techniques about transplantation. Third, incidence and prevalence<strong>of</strong> diseases have increased around the world, particularly ESRD 11 . Finally, the graft is setat zero price, as the law in most countries does not permit paying for organs 12 , whichmeans an infinite demand from an economic point <strong>of</strong> view.Another point to highlight is the nature <strong>of</strong> the supply side <strong>of</strong> organ transplantation. For anorgan to be removed, several requirements need to be met. First, the potential donor musthave healthy and well-functioning organs and be free <strong>of</strong> infection and cancer. Second, inmost <strong>of</strong> the cases the cadaveric donation comes from a donor that is declared brain dead,i.e. the donor had suffered complete and irreversible loss <strong>of</strong> all brain functions. To bedeclared brain dead, more than one physician carries out a full range <strong>of</strong> tests, and at leastone <strong>of</strong> them must be not related to the transplantation proceedings. After that, the hospitalmust then communicate the organ procurement to find the recipient that best matcheswith the available organ. Third, the consent for donation needs to be obtained, which<strong>of</strong>ten comes from the donor’s family. Finally, if consent is given, the organ from thedonor must be removed and allocated to the recipient.The above process typically breaks down at one or more stages, resulting in a failure tocollect the organs. Brain death may not be confirmed given the absence <strong>of</strong> staff or11 The ESRD prevalence rate has increased drastically, particularly in North America. In the USA, it wasreported an increasing <strong>of</strong> 70% in the number <strong>of</strong> people on chronic maintenance dialyse from 1991 (573 permillion population -pmp) to 2000 (977 pmp) (Renal Network, 2006). In Europe, this rate was 1360 pmp in1991 and 1393 in 2001 (USRDS, 2006). The lowest prevalence rate <strong>of</strong> replacement therapy was reportedin Latin America, which increased from 119 pmp in 1991 to 352 pmp, a huge increase <strong>of</strong> 295% over tenyears. It is not just the prevalence rate <strong>of</strong> ESRD patients that is increasing, but also the incidence rate. Itmeans that more people are diagnosed as having ESRD, aggravating even more the problem.12 Just in Iran and the Philippines organ sales are legal.5

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong>hospital’s infrastructure 13 , the hospital may not communicate fast enough that there is anorgan available, the request for consent may not be made in a competent way, and theorgan procurement may not be efficient in the logistics <strong>of</strong> matching the donor to therecipient. Because <strong>of</strong> these problems, it has been estimated that only about 1% <strong>of</strong> alldeaths in the USA occur under circumstances that would allow the organs <strong>of</strong> the deceasedto be used in transplantation (Kaserman and Barnett, 2002).Because <strong>of</strong> the inadequate organ supply, the organ shortage is increasing worldwide, witha few exceptions such as Spain. In Brazil, the organ shortage rose 54% from 2001 to2005. In the UK, it increased 43% in 8 years (1998-2005). In the same period, the USAreported an increase <strong>of</strong> 56% in organ shortage. Consequently, the length <strong>of</strong> waiting timesis increasing, causing further suffering to patients and considerable expense to keep themalive, as well as deterioration <strong>of</strong> the patients’ health throughout the time, which can causethem to be too debilitated to undergo the transplant operation.Living donors are another option for reducing the gap between demand and supply <strong>of</strong>organs. However, it is still seen as a controversial issue in the medical community. Eitherrelated donors (parental) or unrelated donors (altruist) are considered with suspicion by arepresentative number <strong>of</strong> transplant centres, since the donation could be influenced byfamily pressure and psychiatric disorder, respectively (Hou, 2000). Another concernabout using a living donor is that someone can <strong>of</strong>fer some kind <strong>of</strong> monetary benefit for apotential donor, especially for poor and less educated people who have a weak bargainingpower, to donate a kidney (Anbarci and Caglayan, 2005). Based on this, some specialistsbelieve that the priority should be placed on cadaveric donor.3. Data and Methods3.1 Data: Source and Description13 Faults in the detection process <strong>of</strong> brain death are the main reason for losing potential donors (Matesanz,2001). The main recommendations to improve that problem are: i) increase the number <strong>of</strong> intensive carebeds, especially in neurosurgical units; and ii) increase the number <strong>of</strong> nurses and physicians available(Cameron and Forsythe, 2001).6

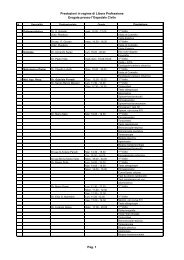

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong>The data come from the Transplant Procurement Management Organization (TPM), theWorld <strong>Health</strong> Organization (WHO), World Bank (WB) and the SociedadLatinoamericana de Nefrología e Hipertensión (SLANH). The sample contains 34countries 14 over 5-year period (1998-2002). The choice <strong>of</strong> the countries is related toavailability <strong>of</strong> data 15 .The variables used in this paper follow Abadie and Gay (2004), Healy (2005) andAnbarci and Caglayan (2005). They are: number <strong>of</strong> deaths by traffic accident per 100,000population; number <strong>of</strong> deaths by brain vascular disease per 100,000 population, GDP percapita; total health expenditure per capita; percentage <strong>of</strong> population that has access to theInternet; dummy for catholic country (=1 if 50% or more <strong>of</strong> population are catholic); anddummy for legal system (=1 if the country has common law). The dependent variable isthe rate <strong>of</strong> cadaveric organ donation per million population (pmp) and the variable <strong>of</strong>interest is a dummy for countries that have presumed consent as law on organ donation.Figure 1 shows a panoramic view <strong>of</strong> cadaveric organ donation in the sample. In the upperhalf <strong>of</strong> the Figure are countries with presumed consent law on cadaveric organ donationand the other half in blue are countries with informed consent. Spain has the highestdonation rates, followed by Austria and Portugal, these three countries having presumedconsent law. In 2002, the USA had the highest donation rate <strong>of</strong> the countries withinformed consent law, and which was close to the rates achieved by Austria and Portugalthat year. In 2002, on average, cadaveric organ donation rate by countries that havepresumed consent was 14.91 pmp, and 10.51 for countries with informed consent.Countries with presumed consent had an increase <strong>of</strong> 12% in their rates from 1998 to 2002,while the others a decrease <strong>of</strong> 12%. In absolute value, Italy was the country that14 The 34 countries we have analyzed in this paper are reported in Table 1.15 A well-known problem in health empirical works is the presence <strong>of</strong> some missing values, particularlywhen the analysis uses countries over time. Our sample has 4% missing values, related to two variables:number <strong>of</strong> deaths from celebro-vascular diseases and number <strong>of</strong> deaths from traffic accidents. If we dropthese missing values, 20% <strong>of</strong> the sample information would be missed. To avoid this loss, we imputedvalues from an OLS trend, using the previous four years. We believe that this method is a good way to treatthe problem, since there are very small variations over years for brain diseases and traffic accident.7

<strong>Azienda</strong> <strong>Ospedaliera</strong> Nazionale“SS. Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo”<strong>Working</strong> <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Health</strong>nr. 3/<strong>2012</strong>improved its cadaveric donation most, with an increase <strong>of</strong> 5.8 (12.3 in 1998 to 18.1 in2002). Brazil is one <strong>of</strong> the countries that do most transplants in the world, but itscadaveric organ donation pmp is one <strong>of</strong> the lowest (4.16 on average among 1998-2002).Figure 1: Cadaveric organ donation per million population (pmp) by country (1998-2002)Cadaveric Organ Donation rate pmpCountriesPanamaGreeceSlovakCroatiaIsraelCosta RicaSwedenPolandNorwayCzech RepublicHungaryLatviaFinlandItalySloveniaFrancePortugalAustriaSpainRomaniaVenezuelaBrazilArgentinaChileNew ZealandSwitzerlandAustraliaGermanyNetherlandsDenmarkCanadaUKIrelandUSA0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 4020021998Brazil was the only country that changed the law on organ donation during the yearsanalyzed in this paper, as presumed consent commenced in 1998. At this time, everyBrazilian citizen became a potential donor after death, unless he/she had registered anobjection against donation in personal documents. However, this law was highlycriticized by different institutions. Due to this pressure, the Brazilian governmentabolished presumed consent in 2000. The main problems related to the Brazilianexperience with presumed consent were: i) lack <strong>of</strong> ample discussion about organ8