Dear Reader:

2017 was for me, personally, an ambivalent year for mainstream movies. What I mean is, there were films people loved that I only dispassionately liked, films people liked that I couldn’t stand, films people disliked that I found absurdly bad, or films people couldn’t make their mind up about but I forged my opinion strongly in the hate column. And then there were films that disappointed me. If I started naming them all (even an Oscar winner), who knows what the blow-back, if any, could be.

However, I am going to single one out specifically, that being 2017’s IT: Chapter One. That’s right people, the sleeper hit film IT, which grossed $700M at the global box office, making it the highest grossing horror film and the third highest grossing R-rated film of all time, the critical darling where the critics and audience ratings actually lined up on Rotten Tomatoes (85/84). Yep, it was a commercial and critical success with a sequel coming in September 2019. But guess who didn’t end up liking it?

Now, I don’t know if this is the case for everyone, but when I have no expectations for something (say, like Free Fire, Pirates of the Caribbean 5, or Alien: Covenant) and I hate it, the sting is less poignant. In contrast, I was actually more hyped for IT than I was for The Last Jedi, a deeper wound considering how I feel about both of those films (yeah, I’m never openin’ that can of worms).

Now, let’s set up our critical framework, shall we? If you’ve read anything else on this blog, you may notice I generally try to stay critical or academic rather than stating whether I liked or disliked a film (Man of Steel being the exception). Therefore, an out and out editorial isn’t something I’ve gravitated towards until now. For the record, I have read Stephen King’s original novel, seen the 1990 TV miniseries, and, obviously, watched the 2017 adaptation. None of those texts – written, televised, or cinematic – is perfect, something I’ll be addressing. For the first theatrical installment (part 2 here) in particular, I would like to state the aspects I really liked:

- The set and production design (ominous small town Derry looked great),

- The casting and performances (Muschietti’s direction was effective, with a standout portrayal from Sophia Lillis’ Beverly),

- The design and execution of Pennywise (Bill Skarsgård crafted his own creepy interpretation),

- Most of the horror set pieces were well-constructed and tense,

- They commit fully to the R-rating, and

- The Wallfisch score and Chung’s cinematography (aurally and aesthetically, the film worked).

Like the close-reading examination of Man of Steel, my issues are with story and character choices primarily, with a special place for thematic criticism.

First, a small overview of the plot, if for some reason you have found yourself here and are completely in the dark. Stephen King’s best-selling and award-winning novel was originally released in 1986. The story follows two intersecting narratives, one set in 1957-8 and the other in 1984-5, but both revolving around the “Loser’s Club,” a group of seven outcasts living in the ominous small-town of Derry, Maine. Each is a victimized outsider in Derry’s supernaturally-oppressive milieu: Bill for his severe stutter, Beverly as the wrong-side-of-the-tracks tomboy; Ben for his weight and status as town newcomer; Eddie for his frail and hypochondriac frame; Richie for his crass and clownish behavior; and Mike, as one of the few Black kids who actually ventures into town.

However, strange things are afoot and the seven band together to fight the supernatural entity that may be the source of all the evil in the town. In the meantime, they have to handle over-the-top bullies, apathetic adults, and a pervasive threat to all the town’s innocent children. Twenty-five-years later, the group reunites as their destiny in Derry might just be beginning. Let’s get to the book, shall we?

Stephen King’s IT (1986)

King conceived of the idea for IT in 1978, wherein the killer was originally a troll rather than a clown. Whether this be coincidence or not, the late-1970s was the beginning of the “creepy clown” in the collective (North) American cultural consciousness. That’s right folks, clowns weren’t always creepy and neither are they globally creepy. Italy in fact loves the THREE creepiest human-like uncanny valley subjects – clowns, dolls, and puppets, but here in the U.S., they are definitely nightmare material.

DETOUR INTO “Creepy Clowns in Context” BECAUSE LEE DID TOO MUCH CLOWN RESEARCH

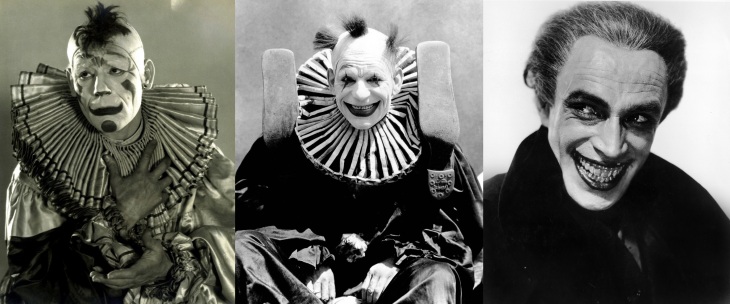

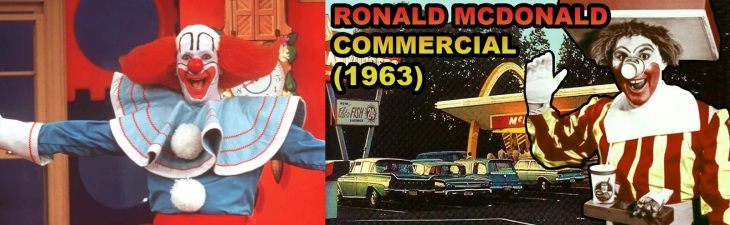

The art of clowning has been around for centuries, but in media, they had a pretty steady and profitable reputation. As disturbing as the murderous clowns or clownish villains are in Laugh, Clown, Laugh (1924), He Who Gets Slapped (1928), The Man Who Laughs (1928), and Freaks (1932), many of which involve Lon Chaney killing himself for some reason, there are far more positive portrayals. My parents, who grew up from the 1960s to the 1970s, both said clowns weren’t considered creepy when they were kids, they were on TV, in cartoons, etc. Also, clowns were oddly class-based (with a tad of racial factors), if you couldn’t afford to go the circus or hire one for a party then you rarely ever saw one in person. Bozo the Clown was a popular clown character across radio and television, reaching his peak in the 1960s, and McDonald’s (which also blew up in the 1960s) introduced Ronald McDonald in 1963.

Then came the 1970s’.

Suddenly you got slashers like The Clown Murders (1976), a young clown-mask-wearing Michael Myers killing his sister in Halloween (1978), and the coup de grâce, the capture of John Wayne Gacy (the “Killer Clown”). You know, in 1978, when King came up with IT. Complete coincidence I’m sure. Gacy, who devised the character of “Pogo the Clown” to participate at fundraisers and birthday parties but was also totally down for brutally killing young men in his part time. Gacy’s trial ran throughout 1980, where all the lurid details came out, and King started writing IT in 1981, to be finished and released in 1986.

Next thing you know, you’ve got the scary clown from Poltergeist (1982), the surreal clown nightmare in Brave Little Toaster (1987), the infamous good-bad film Killer Clowns from Outer Space (1988), the introduction of Simpsons’ Bozo-like Krusty the Clown (1989), and Clownhouse (1989) where the director molested the lead child actor (catch Victor’s Salva new movie on Netflix, Jeepers Creepers 3: Convicted Pedophiles Still Gotta Work). Then came the miniseries TV adaptation of IT in 1990. From there, it explodes further with Gacy films, the “Can’t sleep. Clown will eat me” Simpsons meme, WWF personas, Air Bud’s clown villain “Slappy Happy,” Spawn, American Horror Story: Freak Show, and too many killer clown films to list here sprinkled throughout (like freaking seriously, too many to list).

Now we got IT: Chapter One, clown-only screenings, clowns criticizing the film for demonizing their profession, and small-town sprees of creepy clown sightings.

REALLY THIS TIME, BACK TO THE BOOK

King’s novel has its pros and cons, like any text. But boiling it down, the biggest complaints (some of which are common to King’s canon in general) are the book’s length, the ending and exposition of the creature, and most infamously, the sexualization of eleven-year-olds. Many of these cons are the flip side of the novel’s greatest strengths: the world-building, characters, interesting structure, and thematic exploration of innocence, childhood, coming-of-age, and in my opinion, nostalgia. [The theme of nostalgia will come more into play when contrasted with the 2017 adaptation.]

>>>>>[SPOILERS AHEAD OBVIOUSLY]<<<<<

My personal copy of IT is over a thousand pages, a bulk of which is devoted to the aforementioned world building, atmosphere, character interiority, etc., therefore, the actual plot length is deceiving. The misleading length of the overall novel is a main source of the narrative’s force. Structurally, IT has twenty-three chapters, which are broken down into five parts, and furthermore, are punctuated by the “Derry Interludes,” all ending in an epilogue.

Part I begins with the death of Georgie Denbrough in 1957, followed by the homophobia-driven death of Adrian Mellon in 1984, and ends with Mike Hanlon alerting all six “Losers” that IT has returned to terrorize Derry.

Now well into their late-30s, all the former members have led separate lives since leaving the small town. Bill is a famous horror novelist turned Hollywood screenwriter who is married to an actress that resembles Beverly. Ben is a lean and famous architect. Beverly owns her own fashion company, but is unfortunately married to a man just as abusive as her father. Richie is a famous stand-up comedian and radio shock jock. Eddie runs a successful celebrity limo business and is married to a woman resembling his overbearing mother. Mike remained in Derry, becoming the town’s librarian and de facto historian, in case IT should ever return. Stan is a successful lawyer and loving husband until he gets Mike’s call, committing suicide in the bathroom rather than face IT again.

From left to right: (Top row) Ben, Stan, Richie, Pennwyise, and Eddie; (Bottom row) Mike, Beverly, and Bill

Parts II and IV are set in the summer of 1958, relaying the formation of the “Loser’s Club.” Moreover, each has an encounter with IT and town-bully Henry Bowers, resulting in their shared experiences and drive to discover and destroy Pennwyise. Part III follows five of the “Losers” who have returned to Derry (Stan withstanding) in 1985 as grownups, who struggle to remember the nightmare of that summer. The “Derry Interludes” are diary entries from Mike’s perspective as he catalogs Derry’s violent history and relives his own nightmarish memories.

Note: Informally known as the “Derry Disease,” the loss of memories after leaving Derry effects every “Loser” except for Mike, the only one who stayed behind. Hence, when all the adult “Losers” get the call, each feels drawn back because of their blood promise, but none actually recall what happened until they are within town limits. For those who live in Derry, this disease translates to willful ignorance of the evil at the town’s core.

Part V shows the convergence of the kids’ and adults’ plots to kill the creature once and for all, unsuccessfully in 1958 and successfully in 1985.

A few years ago I was reading one of King’s other books entitled Desperation (1996), wherein complete strangers are drawn to the eponymous abandoned mining town and it gets crazier from there. The characters were very colorfully drawn, the violence and isolation visceral, and the mystery intriguing. Then it got around to explaining what happened to the town and why, and like many of his books, it kind of fell apart for me. Similarly, before I read IT or saw the miniseries, my older brother watched it with my mother. He repeated that same criticism – IT is really scary until you find out what Pennywise is supposed to be. This brings us to the ending and exposition of the creature as well as the novel’s most controversial and notorious scene.

>>>>>[SERIOUSLY BIZARRE SPOILERS AHEAD]<<<<<

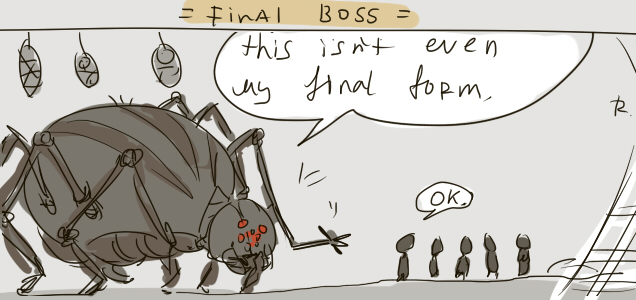

In the miniseries, IT is revealed to be a giant spider from space who takes the form of the victim’s worse fear – the ghost of Bill’s brother, a werewolf, a mummy, etc. – but primarily sticks to the clown schtick. People, even in 1990, were greatly disappointed by this ending. But when you go back to the source material (and what the 2017 adaptation may do), it actually makes perfect sense. Ok, I’m going to attempt to explain what IT really is. Attempt being the operative word.

IT is a cosmic entity.

The universe as we know it was created by a giant extra-cosmic turtle called Maturin, who also created IT. For people who read The Dark Tower series (which I do not), he’s some kind of guardian that protects one of the beams that holds up the “Tower.” He existed before our universe, and one day sprang forth from his shell, and vomited our universe into creation. He’s generally a benevolent force who rarely intervenes in human existence (except he does talk to Bill in 1958).

Somewhere between the events of 1958 and 1985, the Turtle dies. Somehow, due to their psychic connection with each other, the “Loser’s Club” is aware that the word “Turtle” holds great significance. When the Turtle advises young Bill, he informs him of the only way to defeat IT – a mental battle of wits between dueling forces known as the Ritual of Chüd. In 1958, Bill wins and they wound it with pieces of silver which the club believe will harm him. They believe, hence it is true. He, however, does not die and returns in 1984 and is defeated by some of the grownup “Losers.” Furthermore, any offspring he may have had are also killed in egg form.

After reading all of that, does it now make perfect sense why they stuck with an alien spider? Could you imagine trying to explain all that crazy sh** in anything other than a Stranger Things-length miniseries? That’s possibly why King adaptations across mediums are so varied, from the great and solid to the forgettable and bad. For any The Shining (1980) and Carrie (1976), you have The Lawnmower Man (1992) and Maximum Overdrive (1986). In 2017 alone, you have IT: Chapter One and The Dark Tower competing in theaters along with Gerald’s Game and 1922 on Netflix. King’s work is the definition of mixed bag when it comes to adaptations. Often the best adaptations work because they aren’t supernaturally-based, are short stories or novellas rather than full-length novels, or change a lot in the process to the screen, just look at Stand By Me (1986) and Shawshank Redemption (1994).

Basically, the book is long for a reason, fleshing out the world and bigotry of Derry, and how its evil goes back to its inception. Derry feels like a real place, a real small town in America. Most of the book works, but any exposition would’ve been tedious regardless and any unambiguous conclusion about the creature’s origins would have see-sawed between bizarre and confusing or disappointing and excessive.

This begs the question, why does the 2017 adaptation of IT feature several verbal and visual references to the Turtle? What does this mean, I have no idea.

LET’S TALK ABOUT CHILDREN AND SEX

Now that we’ve talked about the ending, shall we address the elephant in the room? Also known as the novel’s child orgy scene. If you somehow got by in life not knowing that the book as a child orgy scene, I’m sorry that you had to learn it here. When I first picked up the book, part of me wanted to know why that scene was in there. For all I know, the book was so well-written that a orgy scene involving 11-12 year olds might make perfect sense. The answer is sort of(?) and not really. Ok, at the end of this 1000+ page book, there is a brief but descriptive six or so page scene after they’ve wounded Pennywise in 1958 and are making their way through the sewers, but have gotten lost. Beverly, an 11-12 year old girl, then takes her clothes off and has sex with all six male members of the “Loser’s Club.”

[PAUSE]

Jesus Christ, why would you end your book this way.

Over the years, King has expressed confusion and frustration due to readers’ and critics’ criticism of this scene where a preteen girl has sex with six boys and it’s actually her idea. To the best of my ability, here’s what I think King may have *“““intended.”””*

As mentioned above, the summer of 1958 draws together these disparate outcast youths to defeat Pennywise. The psychic connection they feel is a result of IT’s continued menacing existence. When the club travels into the sewers, Eddie seems to just know where IT is encamped, like they are psychically drawn to it. However, when they weaken IT, their connection is also weakened, preventing them from collectively finding their way back through the labyrinth of sewer tunnels up to the surface. In this moment of panic and disconnect, Beverly sees the only way to realign their psychic connection is for them all to have sex with her, not with each other, just with her.

Thematically, the book revolves around coming-of-age, innocence, and childhood. That summer, they were children fighting monsters that the adults couldn’t protect them from, hence, they came-of-age and became adults. Therefore, their connection and intimacy as a group of friends came to fruition by crossing the threshold into adulthood together through sexuality, the ultimate and final “connection.” King also tries to write it as Beverly, a victim of physical and psychological abuse from her father (which does have sexual and moralizing tinges), reclaiming her sexuality with her “first loves.”

Adolescent sexuality, its complexity and ambiguity, is a frequent element in King’s work in general (e.g. Carrie). But then King goes into detail about how afraid the boys are, how she talks them into it, their sizes, and finishing and pain and “sweetness.” To speak plainly, it’s really f***ing weird and all together, is an unnecessary scene. Quite simply, it feels like it comes out of nowhere and did not need to be there, hence why every adaptation ignores it and hopes you forget about it. In the miniseries, they have a group hug and in the 2017 adaptation, Beverly becomes a damsel-in-distress and gets unconsensually kissed by Ben like a Disney princess.

That being said, the picture of a White guy, ages 34 to 39, writing this scene out on his typewriter jacked up on tons of cocaine, with his daughter at home who would’ve been 11-years-old when he started writing this book is . . . unsettling.

Stephen King’s IT (1990)

Airing on ABC in November 1990, the IT miniseries is most fondly remembered for the masterful performance of Tim Curry as Pennywise.

Originally to be directed by George A. Romero as an 8-10 hour miniseries, scheduling conflicts shifted directorial duties to co-screenwriter Tommy Lee Wallace, a frequent collaborator of John Carpenter and also director of Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982) and Fright Night 2 (1988). The script was also co-written by Lawrence D. Cohen, screenwriter of Brian De Palma’s Carrie as well as a number of other King TV adaptations. Trimmed to 3+ hours, the two-part miniseries was filmed in Vancouver with 99 percent practical effects and creatively spontaneous Curry taking the stage as the Robin Williams of evil, child-traumatizing clowns. Much remained intact in the adaptation process – the time periods, dual stories, “Loser’s Club” dynamics, etc. [Aside from the aforementioned ending simplification and omission of the orgy scene].

Garnering nearly 30 million viewers over its two-night premiere, IT was considered largely a major success. Over time, the biggest complaints have remained the same. Some are inevitable such as the soap opera acting styles and made-for-TV trappings and production value, while others such as the story’s ending and the comparative weakness of the adult episode as opposed to the kid’s portion are up for discussion. First, let’s give special notice to the effectiveness of IT’s child-focused first episode and the late-Jonathan Brandis in particular, and of course, Curry for giving a perfectly-tuned and commanding performance. As we’ve already hashed out the reason for the shifted ending, let’s explore why IT’s story is perceived as uneven, a criticism the 2019 sequel will have to work really hard at to remedy for fear of facing the same condemnation.

Now, why do people rave over the story of kids facing IT but criticize when the adults return to finish the job?

Essentially, it all goes back to King’s original novel. The structure alternates between the kids’ AND adults’ perspectives, however, the bulk of the adult sections are them remembering events that occurred when they were children. Hence, less meat. Therefore, when the miniseries completely divests the two stories, it becomes like that piece of cake that someone wants because it has the frosting on it, but they cut that piece in half. Is it two pieces of cake? Yes, but one clearly has frosting while the other does not. For me, the Losers as adults have interesting ideas and plot points: Beverly’s abusive marriage, Bill not remembering his brother’s murder, Stan’s suicide, the return of Henry Bowers, and Mike’s lonely life in Derry as the reluctant gatekeeper. In comparison to the kids, it all seemed dull to many people so they padded it out with more of the Ben-Bill-Beverly love story. In reality, only Part III of the book is strictly grownups.

Other factors to consider are casting kids that the audience loves, only to have them absent and replaced by adult actors. In Moonlight, you can cast three actors to play a few characters in a film less than two hours, but for seven characters over a three-hour miniseries is much harder.

The dense romanticized mythology around childhood and children, from folk stories to fairy tales to Stephen King still wields a lot of power. Therefore, scenarios in which kids in peril are much scarier and inherently tense, because their age makes them more vulnerable, weaker, and powerless. You can’t yell “Why don’t they just shoot it with a gun?” when your protagonists are twelve. They are an age set that is supposed to be protected by adults, but in Derry, the adults don’t or won’t save them. Plus, everything seems scarier when you’re a kid, and anything can happen to you. Even worse, kids walk the line between lacking the self-awareness to be afraid of things they should (like a clown in a storm drain) but are characterized as more intuitive to supernatural or freaky occurrences.

And now after roughly 25 years of talking about the novel and miniseries, it is finally time to address my criticisms of the 2017 adaptation. Set off your fireworks and let’s dance. And by that, I mean click here. Thanks!

Pingback: Let the past die . . . Kill IT, if you have to: Race, Gender & Nostalgia in IT (2017) | 24 Frames of Silver: A Cinema Blog for the Soul by Lee O.