Banafsaj | بنفسج | Violet | Viola odorata

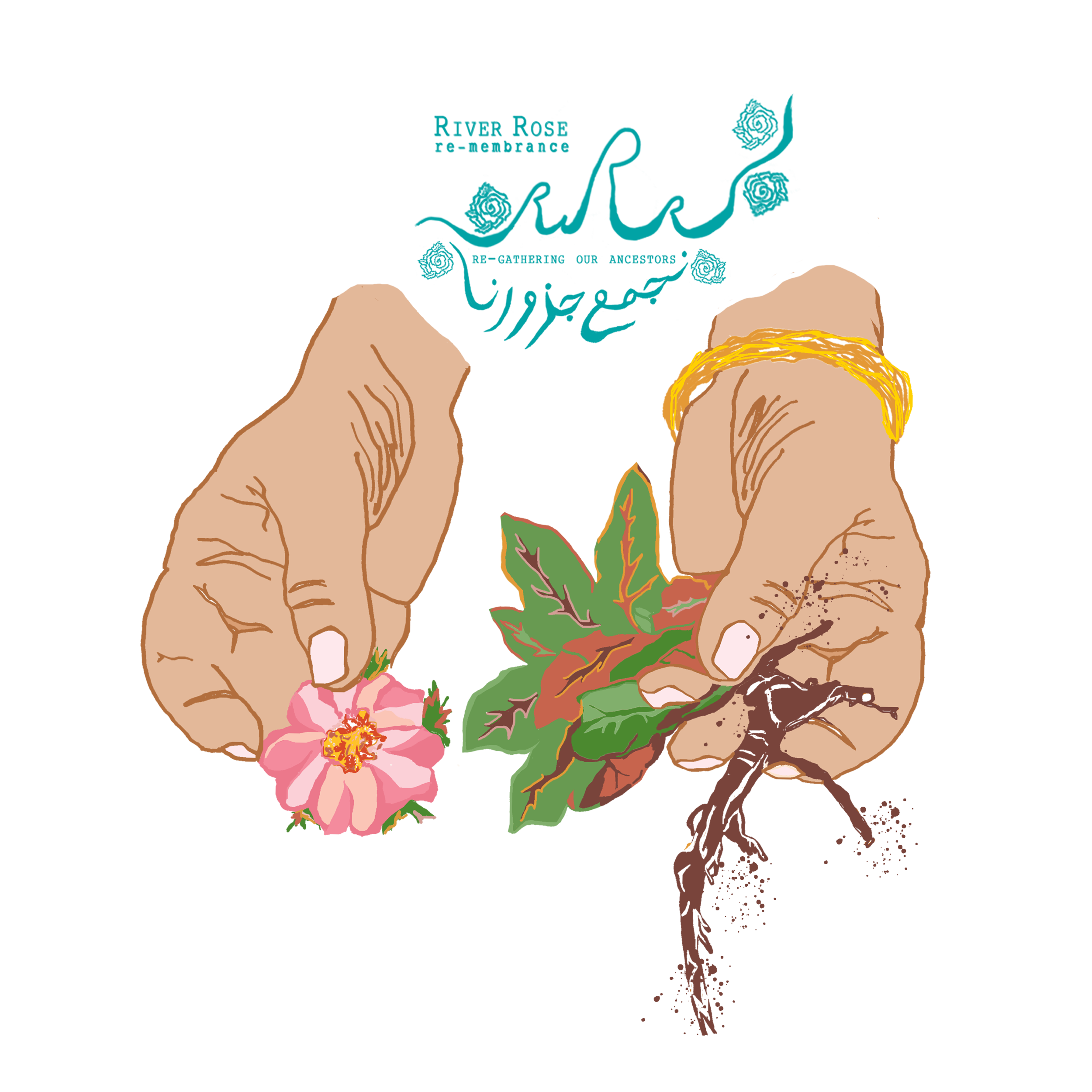

Plantcestor: بنفسج (banafsaj - Arabic), manušak (Armenian), banafsha (Farsi), wunawša, Māzandarāni vanūše, Semnāni benowša (Kurdish), kokulu menekşe (Turkish), Violet, Viola odorata

Also known as: Viola spp., Sweet Violet

Plant family: Violaceae

Parts used: Aerial parts: flowers and leaves

Energetics: Cooling, moistening

Herbal actions: Lymphatic, diaphoretic, alterative, demulcent, decongestant, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, expectorant, antitussive, diuretic, laxative, antiseptic, emetic, nervine, anti-microbial

Constituents: Alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, methyl salicylate, mucilage, vitamin C, flavonoids, minerals (magnesium, calcium, potassium, phosphorus, iron, zinc)

Contraindications: The roots are emetic and can cause vomiting in large doses.

violet

〰️

violet 〰️

Khalil Gibran story about a Violet flower who wanted to become a Rose.

VIOLET AND THE BODY SYSTEMS

Violet is a gentle, safe, and effective plant with many uses for adults, children, and elders alike.

CIRCULATORY: Induces sweating/breaks a fever. Cleanses blood in our bodies. Used for heart disease. Lebanese folk medicine uses flower tea for lowering blood pressure.

DIGESTIVE: Supportive to the spleen, kidneys, and liver. Gentle laxative, can be used to ease constipation in children. Soothes inflammation of the intestines and stomach.

LYMPHATIC: Lymph mover. Used in the treatment of cancer, especially in breast and skin cancer, both preventatively and upon diagnosis. As a poultice, infused oil, as well as internally, it is supportive in breaking down malignant and non-malignant tumors and growths throughout the body. It is an excellent breast rub in the treatment of mastitis, also useful for sore nipples from breast feeding.

NERVOUS SYSTEM: Soothing to the nervous system, calming and easing the emotions. Can be useful in easing insomnia and restlessness while not being intensely sedative.

RESPIRATORY: Ally for treating respiratory and sinus illnesses, colds, and seasonal allergies. Particularly dry coughs, due to their moistening qualities. Especially lovely if you use it as a medicinal honey or syrup.

SKIN: Emollient. Useful in the treatment of eczema, irritation, general skin care.

OTHER: Soothing to the head and chest areas, topically and internally. Antiseptic mouthwash. Used to eliminate cysts. In Lebanon, they are used to treat sprains, for sore eyes, rheumatism, and jaundice.

ENERGETICS AND SPIRIT

Transitions: Help us “shake off winter.” Supporting seasonal transitions and their accompanying discomforts (physically and otherwise). Aiding us to welcome new positive change while we shed what’s passed. Resurrections and rebirths. Supportive during instances of stagnated or sinking states.

Grief, Spirit Realm, Ancestors: Association with grief is common in folklore: “violets are blue.” The color violet has historically been associated with sacredness and the spiritual realm, royalty, alchemical magic, creativity, death, re-birth, transformation, and transcendence.

Used historically in rituals for the dead and to support their transition into the realm of the ancestors.

Dreams and other intuitive realms of knowledge can be opened and gently supported by use of violets, while still encouraging a grounded and embodied presence in our physical and relational human form.

Heartache: Ease, open, and soothe the heart. Emotional restoration. An energetic hug of sorts and especially supporting us to reconcile deep sorrow, loss, and grief. Infused oil rubbed on the chest, light flower infusions, honeys, or baths are especially lovely for this.

“Feel to Heal”: Support the breaking up of emotional and energetic blockages. Facilitate the gentle but truthful release of difficult and dense emotions, turning rocky places inside us into smooth flowing rivers.

Cooling, grounding, and soothing to the internal heat that is created by difficult emotions. Can help effectively transform, cleanse, and liberate the negative or weighty effects of these energies in our spirit and heart when we can’t kick it ourselves. Violets are a loyal and versatile ally, and can instill these qualities in those who receive their medicine.

They are sensitive and sensual while hardy and resilient. Deep feelers with strong persevering roots. Can support the balance and cultivation of these elements in those who are lucky enough to receive their medicine.

Folklore and TRADITIONAL USES:

Violets beckon the start of spring in the hills and mountains of Canaan. Amongst the first flowers to bloom after winter’s snowfall, their appearance in the early springtime associates them with easter, renewal, and rebirth.

Used as a dyeing agent for easter eggs. Flesh gently wrapped around the eggs and covered with tight stockings to leave an imprint when dipped in onion water.

Violets have been used in love conjuring and fertility medicine throughout the ancient and traditional world, perhaps related to their springtime association, not to mention the heart-shaped deep green leaves and sweet soft taste and smell.

Associated with death, some saying that it was one of the flowers that grew in the shadow of the cross Jesus was crucified on.

Associated with humility, and even at times shame, consistently throughout SWANA literature and metaphors because of the way they grow on stems slightly bent with the face of their flowers facing the earth instead of the sky.

They are said to be one of the favored flowers to the Prophet Muhammad, who esteemed them highly and also noted them for having a unique characteristic of “being hot in the winter and cool in the summer”.

ecology and cultivation

There are numerous viola species that grow generously all over the globe from SWANA to East Asia to the Americas, Hawa’i, and beyond.

In their natural habitats, you can often find them growing along rivers or creek-sides, in the mountains, or the understory of forests. They prefer dense shade to full sun and can spread as a ground cover or underneath larger plants that provide shade.

Violets grow about 2-6 inches high and are a low-growing, spreading shrub. Their flowers are viola shaped with 5 petals, often with deep green heart-shaped leaves (some species have different leaf patterns). They are small and humble, with the flowers a stunning color (bright violet purple, bluish purple, or sometimes white or yellow, or multi-colored) and a strong sweet fragrance.

Propagation:

Violets are easy to grow by seed or transplant.

They are self-propagating, spreading seed from hidden pods (underground flowers!) that hide between their leaves rather than from the colored flowers we pick for medicine.

They often show up as volunteers in unexpected places where they were not intentionally planted, and seem to have an affinity for pathways.

They prefer dappled sun or shade and moist, good quality soil, but are resilient and adaptable plants who can grow in very poor and dry soil as well, though the size of their leaves may be slightly smaller as a result.

Harvesting:

Leaf and flower are typically harvested in the spring or early summer when the flowers are still vibrant. Leaf can also be harvested before flowering.

MEDICINAL PREPARATIONS

Infusion:

Approximately 2 teaspoons to a cup of water, or as much as desired.

Tincture:

1:2 fresh herb, 75% alcohol

1:5 dried herb, 40% alcohol

Use vegetable glycerine if you desire to extract the mucilage from the plant, as alcohol will not extract mucilage.

Infused oil:

Slightly wilt fresh flowers (and/or leaves, if desired) before covering with oil and warming. Can use for salves or as is.

Infused medicinal honey or syrup

Excellent child-friendly syrup for instances of sore throat.

Food:

Their leaves and flowers are pleasantly sweet, edible as an addition in salads, candied and sugared in some parts of the world.

On occasion in Lebanon, you can find their flowers prepared into a jam.

Medicinal baths

In Syria, they are used as foot baths for insomnia.

Poultices used for skin irritation and wounds.

an excerpt of traditional Iranian medicinal uses from this source: H. Aʿlam, “BANAFŠA,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, III/6, pp. 665-667, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/banafsa-mid (accessed on 30 December 2012).

BANAFŠA (Mid. Pers. wanafšag, arabicized as banafsaj; cf. the cognate Kurd. wunawša, Māzandarāni vanūše, Semnāni benowša, etc., and the Armenian loanword manušak), common name for the genus Viola L. in New Persian.

Of the very large group of violas distributed in temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, A. Parsa, Flore I, “Violaceae,” pp. 956-70, lists and describes the following 16 species as native to Iran: 1. Viola alba Besser.; 2. V. armena Boiss. & Huet; 3. V. cinera Boiss.; 4. V. ebracteola Fenzl (= V. modesta Fenzl var. parvifloraFenzl); 5. V. hymettia Boiss. & Heldr.; 6. V. kitaibelina Roem. & Shult (= V. tricolorL. var. kitaibelina Ledeb.); 7. V. modesta Fenzl; 8. V. occulta Lehm.; 9. V. odorataL.; 10. V.pachyrrhiza Boiss. & Hoh.; 11. V. riviniana Reich.; 12. V. silvestris (Lam.) Reichb. (= V. caspica Freyn., and the var. mesenderana Freyn. & Sint); 13. V. sintenisii W. Bekr; 14. V. spathulata Willd.; 15. V. suavis M.B. (= V. odorata L. var. suavis Boiss.); 16. V. tricolor L. var. arvensis Murr. (In the 7 published vols. of A. Ghahreman’s Flore de l’Iran, vol. I, no. 40, a new variety, V. spathulata Willd. var. latifolia Ghahreman, and vol. VI, no. 748, the species V. stockssi Boiss. are also found.) Details about these species and varieties may be found in these works. In this article only the V. odorata L. and the V. tricolor L. will be discussed.

The Viola odorata (or some other odoriferous species and varieties popularly assimilated to it), called simply banafša or sometimes banafša-ye īrānī “Iranian violet” (in contradistinction to banafša(-ye) farangī “European violet” i.e., pansy; see below) or banafša-ye moʿaṭṭar/ʿaṭr “the fragrant violet,” grows wild in Iran, typically in out-of-the-way shady cool spots both on high and low lands almost everywhere where climatic conditions are favorable, but, reportedly, it is particularly abundant in Rostamābād (in Gīlān), in Kandavān valley (near Čālūs), in the forest around Rāmsar, and in the woods in Gorgān (for Gorgān, see A. Ḵalīqī, p. 365; cf. banafša-ye ṭabarī “the violet native to Ṭabarestān,” sometimes used in classical Persian poetry to designate it). An old favorite in Iran, this violet is already mentioned in the Bundahišn (tr. Anklesaria, 16.13, pp. 148-49) among plants having sweet-scented blossoms and (16A.2, pp. 152-53) is said to belong to [the Īzad] Tīr. In the text King Xusraw and His Boy (par. 82) it is said that the scent of violets is like the scent of girls.

Violets, whether Viola odorata or others, are not necessarily violet in color: hues ranging from white to deep, blackish purple (including yellow, blue, lilac, dark blue [kabūd], violet, etc.) have been reported. Some earlier historical evidence to this effect can be found in Persian literature and in some works on materia medica: a white violet is attested in the poetry of Manūčehrī Dāmḡānī (d. 432/1040-41; Dīvān, ed. M. Dabīrsīāqī, 5th ed., Tehran, 1363 Š./1984, p. 207); the (dark) blue vault of heaven has been qualified by some as banafšagūn “violet-colored,” and Bīrūnī (362-440/973-1048) quotes Būlos (i.e., Paulus Aeginata, fl. 640) as having written, “Some people use the oil from the purple [banafsaj], some that from the saffron-colored one, and some that from the white one” (Ṣaydana, p. 102; see also below on the color implications in reference to the hair on the head and the down on the face of poets’ sweethearts).

From certain botanical features of violas there have developed some violet-based similes and metaphors in classical Persian literature. The peculiar corollas of violets or, perhaps, a bunch of these suggest ringlets, disheveled or curly hair, or a loose lock of hair. This feature plus the blackish purple color of some varieties, with or without the idea of fragrance, have formed the basis for such a metaphor as banafša : hair, and for such similes as banafša-mūy/zolf “having violety hair,” referring to the hair of some poets’ sweethearts. The poet Qāʾānī Šīrāzī (d. 1270/1853), in the opening distich of a picturesque mosammaṭ (Dīvān, Tehran, 1363 Š./1984, pp. 669-71), has this further heightened comparison for violets: “Violets have grown on brooksides as if the houries of Paradise had loosened their hair” (gosasta ḥūr-eʿīn ze zolf-e ḵᵛīš tārhā). The bluish gray hue of some other varieties has resulted in similes such as banafša-ʿāreż/ʿeḏār “having violety cheeks/face,” referring to the grayish nascent down on the cheeks and upper lip of the poet’s (imaginary) adolescent inamorato (these similes are often chromatically enhanced by a contrast to the color of the cheeks/face compared to lāla “[rosy] tulip” or saman “[white] jasmine”).

Also typically, violets are low-growing plants with inconspicuous, humble, pensive-looking (cf. the etymology of pansy, Viola tricolor, in English) flowers which, in some species, slightly bend on their stalks, as if looking down for shame. Further, they seem to prefer secluded, shady spots (underbrush, hedges, cracks in alpine rocks, etc.), almost overshadowed by neighboring vegetation. A certain combination of these features has given rise in Persian literature to three romantic associations of ideas: (1) modesty, bashfulness, humility; (2) neglectfulness; (3) neglect, regret, sorrowfulness, mournfulness (an Arab author quoted by Šehāb-al-Dīn Aḥmad Nowayrī, 677-733/1278-1332, Nehāyat al-arab XI, p. 229, even compares the sweet violet to “a forsaken lover, resting his head [in grief] on his knee,”—a motif also found in the Persian poet Ḵāqānī, d. 595/1199: “like the violet, I am laying may head on my knees, while these are a thousand times more violetish [i.e., bruised] than my lips”).

Wild sweet-smelling violets may also be naturalized as garden plants. As early as 921/1515-16, the agriculturist Abū Naṣrī Heravī (Eršād al-zerāʿa, pp. 207-08) provides instructions for the cultivation of banafša (in the Herat area), of which he mentions three varieties: “dark blue, both double (sad-barg, lit., “centipetalous”) and ordinary (rasmī), purple, and white.” Eʿtemād-al-Salṭana, in his al-Maʾāṯer wa’l-āṯār I (ed. Ī. Afšār, Tehran, 1363 Š./1984, p. 136), which records all the innovations and achievements during the first forty years of the Qajar Nāṣer-al-Dīn Shah’s reign (1264-1313/1848-96), mentions the cultivation of “three hues of double [por-par] Iranian violets” as well as the introduction of “three varieties of pansies [banafša-ye farangī]” in city gardens in Tehran. Incidentally, Abū Naṣrī Heravī (op. cit., p. 223) also mentions a banafša-ye kūhī, lit., “mountain violet,” “whose plant grows up to half a cubit high, and whose flowers are purple and fragrant.”

Wild pansy, V. tricolor L. var. arvensis Murr., grows in woods and meadows in the north, northwest, and west of Iran as well as in the Alborz and Tehran regions (see Ghahreman, op. cit., VI, no. 749). In contrast to its fragrant relative, V. odorata, it is scentless (this may account for its local Māzandarāni name vasnī-benafše, mentioned by Ghahreman, ibid., lit., “violet of the vasnī [i.e., the co-wife]”). The cultivated, hybridized pansy, V. tricolor var. hortensis, generally called banafša-ye farangī “European violet,” as indicated by its Persian epithet and by Eʿtemād-al-Salṭana (see above), is a rather new addition to garden flowers in Iran. Although scentless like its wild parent, it has become very popular, because it blooms early in spring and is associated with the Iranian Nowrūz festivities, all the more so as the strange markings on the blooms make them look somewhat like jovial human faces, an anthropomorphism appealing particularly to the Persian imagination.

Phytotherapists or physicians of the Islamic era, generally indifferent to the botanical diversity of native species of Viola, have recognized numerous medicinal properties in banafša/banafsaj (occasionally called forfīr/ferfīr in some Arabic sources; from Gk. porphyra “purple color”) in general, an account of which will be found in most works on traditional materia medica (e.g., in Arabic, Ebn al-Bayṭār, al-Jāmeʿ I, pp. 114-15, and, in Persian, ʿAqīlī Ḵorāsānī, Maḵzan al-adwīa, pp. 127). The earliest reference in Persian works to Viola varieties from a medicinal viewpoint probably is that by Mowaffaq-al-Dīn ʿAlī Heravī, author of the oldest extant independent Persian treatise on materia medica, K. al-abnīa (probably compiled in 339/950?), ed. A. Bahmanyār and Ḥ. Maḥbūbī Ardakānī, p. 67: “The best is [first] banafša-ye kūhī [mountain violet], and then banafša-ye eṣbahānī[Isfahan violet], and the more fragrant [they are, the better]” (on “Isfahan violet,” see also below). Aḵawaynī Boḵārī (d. ca. 373/983?), author of the oldest extant medical text in Persian, Hedāyat al-motaʿallemīn, mentions the following uses for banafša, some of which, absent in previous works, probably are from his personal experiences.

He uses it as part of an enema against quinsy (p. 308);

in a pectoral poultice against a kind of “dry” cough (p. 318);

in an emollient enema against pleurisy (p. 328);

in an enema against ileus (p. 429);

in a hepatic poultice against jaundice (p. 467);

in a dorsal (or lumbar) poultice against nephritis, and in a concoction “to be poured” on the patient’s back in case of suppurative nephritis (p. 482);

in an ointment against vesical inflammation (p. 503);

in an infusion to be used as a sitz-bath against uterine cancer (p. 538);

in a poultice against sciatica (p. 572);

in an infusion “to be poured” on the patient’s head in case of fever caused by sunstroke (p. 649);

in a sitz-bath against fever caused by grief and preoccupation (p. 654);

in baths against hectic fever (pp. 665, 667), etc.

The internal uses of banafšaand of banafša-ye eṣbahānī (the difference between the two is not specified by the author) are:

(banafša) in a mixture (with some other simples) against headache of bilious origin (p. 225);

(banafša preserve) in kašk-āb against vesical inflammation (p. 501);

in a linctus against pleurisy (p. 329);

in a laxative infusion against anorexia (p. 357);

(banafša-ye-eṣbahānī) in an electuary against colic (p. 434);

in a drink with rosewater against hepatic dysfunction (p. 437);

with sugar against tertian fever, etc.

Nowadays, in popular or traditional therapeutics, dried violet blossoms are sometimes used by themselves in infusion as febrifuge, but usually with some other vegetable simples, the best-known combination of which is the č(ah)ār-gol (“the four flowers,” i.e., violets, water lilies, mallows and squash/pumpkin flowers) in a concoction indicated as febrifuge, “coolant,” emollient, or pectoral.

resources

BANAFŠA, Encyclopedia Iranica

Traditional Medicine in Syria: Folk Medicine in Aleppo Governorate