Hydrastis canadensis / Goldenseal

Hydrastis canadensis / Goldenseal

Hydrastis canadensis / Goldenseal

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

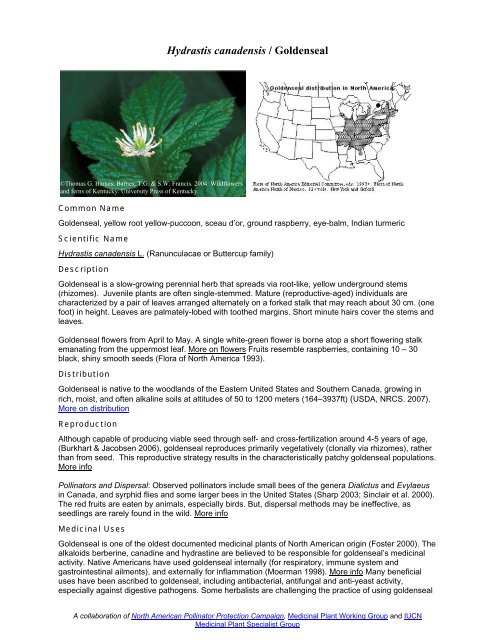

<strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong> / <strong>Goldenseal</strong>©Thomas G. Barnes. Barnes, T.G. & S.W. Francis. 2004. Wildflowersand ferns of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky.Common Name<strong>Goldenseal</strong>, yellow root yellow-puccoon, sceau d’or, ground raspberry, eye-balm, Indian turmericScientific Name<strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong> L. (Ranunculacae or Buttercup family)Description<strong>Goldenseal</strong> is a slow-growing perennial herb that spreads via root-like, yellow underground stems(rhizomes). Juvenile plants are often single-stemmed. Mature (reproductive-aged) individuals arecharacterized by a pair of leaves arranged alternately on a forked stalk that may reach about 30 cm. (onefoot) in height. Leaves are palmately-lobed with toothed margins. Short minute hairs cover the stems andleaves.<strong>Goldenseal</strong> flowers from April to May. A single white-green flower is borne atop a short flowering stalkemanating from the uppermost leaf. More on flowers Fruits resemble raspberries, containing 10 – 30black, shiny smooth seeds (Flora of North America 1993).Distribution<strong>Goldenseal</strong> is native to the woodlands of the Eastern United States and Southern Canada, growing inrich, moist, and often alkaline soils at altitudes of 50 to 1200 meters (164–3937ft) (USDA, NRCS. 2007).More on distributionReproductionAlthough capable of producing viable seed through self- and cross-fertilization around 4-5 years of age,(Burkhart & Jacobsen 2006), goldenseal reproduces primarily vegetatively (clonally via rhizomes), ratherthan from seed. This reproductive strategy results in the characteristically patchy goldenseal populations.More infoPollinators and Dispersal: Observed pollinators include small bees of the genera Dialictus and Evylaeusin Canada, and syrphid flies and some larger bees in the United States (Sharp 2003; Sinclair et al. 2000).The red fruits are eaten by animals, especially birds. But, dispersal methods may be ineffective, asseedlings are rarely found in the wild. More infoMedicinal Uses<strong>Goldenseal</strong> is one of the oldest documented medicinal plants of North American origin (Foster 2000). Thealkaloids berberine, canadine and hydrastine are believed to be responsible for goldenseal’s medicinalactivity. Native Americans have used goldenseal internally (for respiratory, immune system andgastrointestinal ailments), and externally for inflammation (Moerman 1998). More info Many beneficialuses have been ascribed to goldenseal, including antibacterial, antifungal and anti-yeast activity,especially against digestive pathogens. Some herbalists are challenging the practice of using goldensealA collaboration of North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, Medicinal Plant Working Group and IUCNMedicinal Plant Specialist Group

as a first defense against colds and flu, favoring other, more abundant substitutes (Blumenthal 2000;Bergner 1996/7).Trade<strong>Goldenseal</strong> has been a top selling medicinal herb on the international market for many years (Bannerman1997; Sinclair and Catling 2001). A 2007 worldwide market analysis lists goldenseal among the twentyleading herbal supplements (BCC 2007). <strong>Goldenseal</strong> is marketed in over 500 medicinal productsworldwide and is often used in combination with other herbs, especially Echinacea (Bannerman 1997;NatureServe 2007). Powdered root is believed to be the main form of goldenseal in international trade.Though the species is in cultivation, most goldenseal is still wild-collected, according to the AmericanHerbal Products Association (AHPA 2003). Limited supplies from the wild and increased demand haveresulted in increasing prices. Wholesale prices skyrocketed in the 1990s, from about $8.00 to $100.00per pound (Foster 2000). A downturn in prices in 2000 appears to be slowly rebounding and in 2005,Pennsylvania dealers paid an average of $25 per pound of dry root (Burkhart & Jacobsen 2006).Legal Protection and Conservation StatusMajor threats to goldenseal populations are loss of habitat, due to development and logging, and overharvestfor the medicinal trade. Population reductions reported in the core of the goldenseal’s range,including Kentucky and Ohio, have been mainly attributed to over-collecting (Jones & Szymanski 1999;Mulligan 2003). In many areas populations have been completely eliminated by herb collectors and insome areas, poaching is also a problem (NatureServe 2007).In Canada goldenseal is listed as threatened (NatureServe 2007). In the United States, it is listed asendangered, threatened, vulnerable or of special concern in Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland,Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina and Vermont (NatureServe2007). <strong>Goldenseal</strong> is listed as “At Risk” by United Plant Savers. More info<strong>Goldenseal</strong> has been listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in EndangeredSpecies of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 1997. International trade in Appendix-II species must notbe detrimental to the survival of wild populations. However, CITES currently does not regulate goldensealpowder, which is believed to be the main commodity in trade. This situation is currently being reviewed byCITES Parties. More infoSustainable use and conservation<strong>Goldenseal</strong> is a slow-growing perennial forest herb that could easily become commercially extinct unlesswild populations are strictly managed and greater emphasis is given to cultivation. Though the species isin cultivation, it continues to be primarily wild-harvested. Since root harvest results in mortality of theplant, and because wild populations tend to occur in patches, wild goldenseal populations are prone toover-harvest. Sexually reproducing individuals are important for maintaining genetic integrity and diversitywithin each population. The following good stewardship practices can help to maintain or enhance wildgoldenseal populations.Sustainable Actions Wild-harvesters: Find out the legal requirements for wild-harvesting goldenseal in yourstate; rotate harvest areas; thin patches rather than collecting all available plants; leave aportion of mature and juvenile individuals untouched; replant parts of harvested roots (Seealso: Behrens et al. 2002; Burkhart & Jacobsen 2006; Lockard & Swanson 2004). Growers: Find out the legal requirements for cultivating goldenseal in your state; ensureplanting stock is obtained in a way that does not threaten wild populations; consult localexperts and resources for cultivation requirements in your area (See also: Burkhart 2006;Davis & Greenfield 2004; Gladstar, & Hirsch 2000; Lockard & Swanson 2004; Persons &Davis 2005). Practitioners and Consumers: Choose ethically-wildcrafted or verifiably cultivated sourcesof goldenseal bulk herbs or supplements; use goldenseal only when it is best indicated; whenchoosing substitutes, exercise caution not to choose a species that is equally as vulnerableto overharvest (See also: Blumenthal 1999; Blumenthal et al. 2003; Gladstar, & Hirsch 2000).Fact Sheet Author/DateJolie Lonner, Go Wild! Consulting. www.gowildconsulting.com January, 2007.A collaboration of North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, Medicinal Plant Working Group and IUCNMedicinal Plant Specialist Group

ReferencesReferencesAHPA. 2003. Tonnage Survey of North American Wild-harvested Plants, 2000-2001. SilverSpring, Maryland: American Herbal Products Association.Bannerman, J.E. 1997. <strong>Goldenseal</strong> in world trade. Pressures and potentials. Herbalgram 41:51-52.BCC (Business Communications Company). 2007. Herbal Supplements, Prescription Drugs,Rx-to-OTC Products, A Comparison. BCC Research. Wellesley, MassachusettsBehrens, J., S. Schmitt and A. Hamilton. 2002. <strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong>. World Wildlife Fund forNature-United Kingdom (WWF-UK). Bergner P. 1996/1997. <strong>Goldenseal</strong> and the common cold: The antibiotic myth. Med Herbalism8(4):1, 4–6.Blumenthal. M. 1999. The Complete German Commission E Monographs: Therapeutic guideto herbal medicines. American Botanical Council. Austin, Texas.Blumenthal, M. 2000. <strong>Goldenseal</strong> In Gladstar, R. and P. Hirsch. 2000. Planting the future,saving our medicinal herbs. Healing Arts Press. Rochester, Vermont.Blumenthal, M. A. Goldberg, T. Kunz, and K. Dinda. 2003. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs.American Botanical Council. Austin, Texas..Burkhart, E. and M. Jacobsen. 2006. <strong>Goldenseal</strong>: <strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong>. Nontimber ForestProducts (NTFPs) from Pennsylvania. Pennslvania State University. Park, Pennsylvania.Davis, J. and J. Greenfield. 2004. Superb Herbs: 10 medicinal herbs with economic promise.North Carolina Arboretum. Asheville, North Carolina.http://www.ncarboretum.org/Superb_Herbs/goldenseal.htmlEichenberger, M. D. and G. R. Parker. 1976. <strong>Goldenseal</strong> (<strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong> L.)distribution, phenology and biomass in an oak-hickory forest. Ohio Journal of Science76:204-210.Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North ofMexico. 7+ vols. New York and Oxford.http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=115979Integrated Taxonomic Information System on-line database. http://www.itis.usda.gov.Gagnon, D. 1999. A review of the ecology and population biology of <strong>Goldenseal</strong>, and protocolsfor monitoring its populations. Final report to US Fish and Wildlife Service - Office ofScientific Authority. Groupe de recherche en écologie forestière Université du Québec áMontréal. Montreal, Canada.Fletcher, Edward. 2005. COO, Strategic Sourcing, Banner Elk, North Carolina. Personal communication.Foster, S. 2000. The future of goldenseal..Gladstar, R. and P. Hirsch. 2000. Planting the future, saving our medicinal herbs. Healing ArtsPress. Rochester, Vermont.Jones, R.T. and M. Szymanski. 1999. Woods production of ginseng and goldenseal.University of Kentucky Extension. Quicksand, Kentucky..Lockard, A. & A.Q. Swanson. 2004. A Digger’s Guide to medicinal Plants, 2 nd edition.American Botanicals. Eolia, Missouri.Moerman, Daniel E. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Mulligan, M. 2003. Population Loss of <strong>Goldenseal</strong>, <strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong> L., (ranunculaceae),in Ohio. .NatureServe. 2007. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application].Version 6.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. http://www.natureserve.org/explorer.(Accessed: January 10, 2007.)Persons, S. and J. Davis. 2005. Growing and Marketing ginseng, goldenseal and otherwoodland medicinals. Bright Mountain Books, Inc. Fairview, North Carolina.Sanders, S. and J.B. McGraw. 2002. <strong>Goldenseal</strong> (<strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong> L) distribution,abundance, and population dynamics in an Indiana Nature Preserve. Natural Areas JournalA collaboration of North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, Medicinal Plant Working Group and IUCNMedicinal Plant Specialist Group

22(2):129-134.Sharp, P. C. 2003. <strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong> L. (<strong>Goldenseal</strong>) Conservation and Research Plan forNew England. New England Wild Flower Society. Framingham, Massachusetts.Sinclair, A. and P.M. Catling. 2000. Ontario <strong>Goldenseal</strong>, <strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong>, populations inrelation to habitat size, paths, and woodland edges. Canadian Field-Naturalist 114: 652-65.Sinclair A., P.M. Catling, and L. Dumouchel. 2000. Notes on the pollination and dispersal of<strong>Goldenseal</strong>, <strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong> L., in Southwestern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist114: 499-501.Sinclair, A. and P. M. Catling. 2001. Cultivating the increasingly popular medicinal plant,<strong>Goldenseal</strong>: review and update. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 16:131-140Stoltz, L.P. 1994. Commercial production of goldenseal and ginseng. New Crops News: 4 (1)..USDA, NRCS. 2007. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov,17 January 2007).National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA.USFWS-DSA (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-Division of Scientific Authority). 1997. Proposalfor the inclusion of <strong>Hydrastis</strong> <strong>canadensis</strong>, Appendix II. CITES-Convention of the Parties 10.Harare, Zimbabwe.Welty, J. C. 1962. The Life of Birds. W. B. Saunders Company. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.HYPERLINKSDisclaimerThe information contained in fact sheets are not intended nor implied to be a substitute forprofessional medical advice relative to your specific medical condition or question. All medicaland other healthcare information that is given here should be carefully reviewed by theindividual reader and their qualified healthcare professional.More on FlowersThe symmetric flowers have no petals and three greenish-white sepals, which fall off before thefruit matures. <strong>Goldenseal</strong> flowers have 50-75 greenish-white stamens (pollen producing maleparts) and 5-15 pistils (seed bearing female parts).Native American usesNative Americans (including the Blackfoot, Cherokee, Crow, Iroquois, Meskwaki, Micmac, andSeminole) have variously used goldenseal roots internally to treat whooping cough, liver trouble,fever, cancer, earaches, and a variety of gastrointestinal ailments (Persons and Davis 2005).The root is also used externally as a wash for local inflammations (Moerman 1998) More infoMore on distributionU.S.: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas,Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey,New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, WestVirginia, Wisconsin; Canada: Ontario more infoMore on reproductive biology<strong>Goldenseal</strong> seedlings are rarely found in the wild, possibly due to poor seed germination(Sanders and McGraw 2002; Sharp 2003). <strong>Goldenseal</strong> is a clonal species, goldenseal patchesof up to 100 stems in a single square meter have been documented (Gagnon 1999). It is notknown whether large patches represent a single genotype or whether multiple genotypes occurwithin a single patch (Sanders and McGraw 2002). Sinclair and Catling (2000) postulate that thefrequent occurrences of goldenseal in isolated patches suggest potential limitations to itsspread.More on dispersalResearchers note that fruits disappear when ripe and that few are found on the ground (Sinclairand Catling, 2000; Eichenberger and Parker 1976), suggesting that the fruits are being eaten.A collaboration of North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, Medicinal Plant Working Group and IUCNMedicinal Plant Specialist Group

Birds may be the primary consumers of goldenseal fruit (Welty, 1962). The fact that seedlingsare rarely found outside established populations may reflect the ineffectiveness of dispersalmethods (such as damage to seeds caused by the predator’s digestive system) or may resultfrom intrinsic factors (such as low seed germination; Sanders and McGraw 2002; Sharp 2003).More on goldenseal trade<strong>Goldenseal</strong> roots, plants, leaves, seeds, fruits and whole plants are sold in many forms:powdered, dried or fresh. Fresh goldenseal roots and live plants are used primarily as plantingstock for cultivation purposes. Approximately 2-4000 pounds per year of goldenseal leaves arecollected on a small-scale to make teas and tinctures (Edward Fletcher, COO, StrategicSourcing, Banner Elk, North Carolina, pers. comm. 2005).It is estimated that 60% of domestic production is sold within the United States and the rest isexported (E. Fletcher, pers. comm. 2005). Powdered root is believed to be the predominantform of goldenseal in international trade, but the actual amount is unquantifiable becauseCITES does not currently regulate powdered goldenseal and the species is not otherwisetracked in trade.More on AHPA Tonnage SurveysAccording to a study by the American Herbal Products Association, a yearly average of 155,000pounds of dried goldenseal was produced from 1998 to 2001. Of this amount, 82% was wildharvested(AHPA 2003). Estimating the average number of roots per pound, the total numberof goldenseal plants harvested from 1998-2001 is said to be between 5.5 million and 50 millionindividual plants, of which anywhere from 4.5 million to 40 million plants were wild-harvested(AHPA 2003).More on goldenseal cultivationMost goldenseal in cultivation is vegetatively propagated, grown from rhizome pieces or rootcuttings. Cultivated goldenseal can produce marketable roots within 3-7 years, a feat that wouldtake a wild plant 4 to 5 times longer to produce under ideal conditions (Gagnon 1999).Cultivated goldenseal roots bring the same price as wild roots (Jones & Szymanski 1999).Although it is possible to cultivate goldenseal from seed, few commercial-scale producers do sobecause of rapid loss in seed viability (must be planted within 2-3 days), low germinationsuccess (averaging 60%), and longer time investment (it can take 5-7 years to get a crop).<strong>Goldenseal</strong> grows best under the same conditions in which it is found in the wild, including ashade requirement. Cultivated goldenseal is thus either planted in a woodland setting or undera shade structure. <strong>Goldenseal</strong> also shares the same cultural requirements as Americanginseng (Panax quinquefolius) and is suggested as a good crop for companion-planting or croprotation (Jones and Szymanski, 1999; Stoltz, 1994).Local conditions are an important consideration when cultivating goldenseal. These linksprovide a starting point. We also suggest that you contact the Extension Service in your area.• Kentucky• North Carolina• PennsylvaniaMore on CITES Appendix IIWhen there are concerns that unregulated international trade might be detrimental to thesurvival of wild populations of plants or animals, the species may be added to CITES. For anAppendix-II species, the role of CITES Parties (countries that are members to CITES) is toensure that species in international trade have been legally obtained (i.e. all pertinent laws werefollowed in acquiring the commodity) and that the trade does not pose a threat to the survival ofthe species. To determine whether a species is listed on the CITES Appendices, search theCITES-listed species database. For more information see the CITES Web site at:A collaboration of North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, Medicinal Plant Working Group and IUCNMedicinal Plant Specialist Group