ArtSeen

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini: Works from 1960 to 1990

Florence Lynch Gallery March 20 – May 3, 2008

Florence Lynch Gallery has mounted a unique exhibit of 43 paintings, photographs, assemblages and performance videos by underground legend Guglielmo Achille Cavellini. He was a multidimensional creator—an art dealer, collector, and innovator, to name just a few of his titles. He is frequently associated with the international avant-garde, the Fluxus movement, abstract painting, mail-art and assemblage. His work constitutes an important artistic bridge between postwar Italian experimentation and American Pop.

Born into an old Tuscan family in Brescia on September 11, 1914, he began to draw during his military service and made caricatures of his fellow soldiers. After World War II, he began to exhibit the works of Vedova and San Tomaso in his home in Villa Bonomese in Brescia. The town was scandalized by the show, but the works attracted the attention of younger Italian artists, many of whom were to remain in contact with Cavellini throughout his life.

He first became involved with art collecting in 1956 while visiting Venice, where he discovered the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. He was instantly enthralled by Jackson Pollock’s works in particular, and inquired about their prices. When he decided to make a purchase, a curator informed him that Pollock had died just a few days earlier, and that his work was no longer for sale. This encounter, however, sparked Cavellini’s interest in American art, which was to have a major impact on his own art as well as his collection.

Cavellini subsequently purchased work by Franz Kline, Gottlieb and Cy Twombly. The artist’s son, Piero Cavellini, recounts in an essay in this show’s catalogue that it was “the advent of Pop Art—which broke through the 1964 Venice Biennial like a tidal wave—that led Cavellini to fully understood how strong and impressive this avant-garde art really was.”

For 50 years, Cavellini practiced an “art without boundaries.” He might be categorized as second-generation avant-garde, transcending forms adopted by Futurism and Surrealism to create Neo-Dada, taking it to the level of inter-art or poly-art—in other words, a multimedia hybrid. For example, he invented “self-historization,” a conceptual form of self-promotion as well as a way of archiving his collection, performances and mail-art by writing his comments on walls, canvases, clothes and even on the flesh of nude models, inscribing his autobiographical events and then photographing them for posterity. Another stunt was to print his surreal achievements onto photo-montage/painted-collage, the “impertinent self-portraits 1974/84,” as he titled them.

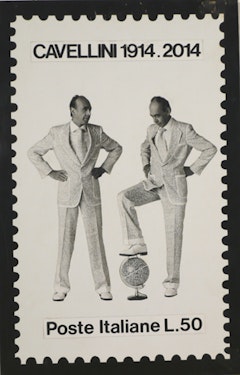

The current show also features some photographs from Cavellini’s Italian postage-stamp series (1973)—pictures of the artist with handwriting covering his tuxedo, hat, underwear, luggage and mannequins—all cut with a crinkly border like an old-fashioned postage stamp. Some of the postage stamps on display are marked for the his “imaginary centenary” (1914-2014), depicting the artist dressed in a white suit and tie, covered with handwriting, holding an umbrella similarly scribbled upon. Another of his “faux-postal stamps” is a poster advertising a future Guggenheim retrospective that has yet to happen.

Cavellini had a mailing list of more than 10,000 correspondents to whom he sent catalogues and mail-art papers. During the 1950s, he contributed fictional autobiographical pieces to weeklies and art magazines (e.g., Il Mondo and L’Europeo) telling tales such as his visit with Mao Tse Tung. But all of this playful activity served merely as parentheses to his love of painting, and in 1962, after a period of depression, he once again took up his brushes. By 1965, he was showing his latest work in Milan at the Galleria Apollinaire. At this point, something extraordinary happened: Cavellini began to destroy his works for the purpose of reconstructing them into sculpture, a new fixation. Some of this work is present at the show in the form of boxes and crates in which destroyed works can be glimpsed through the slats.

One of the sculptures, “Casa N. 106,” is a crate that contains destroyed work from 1966/69, of wood and cobalt blue pigment, representative of that period. Another crate is the “Crate Containing Destroyed Work N. 100,” with a piece of intact art sandwiched between two deliberately charred works. In other works, images of the Empire State building and an appropriation of Andy Warhol celebrity portraits on charred wood reveals his conviction that “fire is a universal element of change” and charcoal is an “intimate ultra-living element” as Gaston Bachelard describes it in his book, Psychoanalysis of Fire. He also began to repaint the photographs of the works he himself had destroyed, printing their images on emulsion canvas, fusing the art of painting with the magic of photography.

In the ‘70s, Cavellini became involved with mail-art, and his favorite medium became photography. In a series he called “Analogies,” he placed black-and-white self-portraits on boards and added color to create picture stamps of himself alongside images of Marcel Duchamp, the Mona Lisa, and Pablo Picasso. One of the most interesting works of that time is a self-portrait with multiple masked images of the artist (scribbled upon, of course) surrounding an unmasked self-portrait.

I met Cavellini in 1982, during his trip to New York, when he visited my studio in Manhattan and spent some time with Ray Johnson’s circle of friends: the late Carlo Pittore, the late Buster Cleveland and of course Ed Higgins III, who painted his body as a performance piece in red, white and green, the colors of the Italian flag. In addition, as his son notes, “several thousand of his stickers, which celebrated his centennial, appeared in the streets of California and New York.”

He was praised as the “king of alternative art” at the Inter-Dada Festival of 1980, in California. Wearing clothes covered in writing, he attached stickers and stamps to everyone who attended. But it was in Manhattan that he engineered perhaps his most memorable event, when he turned into a living statue, his body covered with stickers and acrylic paint.

The scope and dimension of Cavellini’s self-aggrandizing and self-promotion rivals that of Salvador Dali; indeed, Cavellini is a true Daliesque character, a brilliant, experimental post-surrealist whose work is finally reaching a wide audience.