*All reviews contain spoilers*

Disclaimer: This blog is purely recreational and not for profit. Any material, including images and/or video footage, is property of their respective companies, unless stated otherwise. The author claims no ownership of this material. The opinions expressed therein reflect those of the author and are not to be viewed as factual documentation. All screencaps are from Animationscreencaps.com.

Cast –

Sandra Bullock – Miriam (speaking)

Amick Byram – Moses (singing)

Brenda Chapman – Miriam (singing, partial)

Aria Noelle Curzon – Jethrodiadah (Tzipporah’s youngest sister)

Sally Dworsky – Miriam (singing, partial)

Ralph Fiennes – Rameses

Danny Glover – Jethro (speaking)

Jeff Goldblum – Aaron

Ofra Haza – Yocheved

Val Kilmer – Moses (speaking) and God

Steve Martin – Hotep

Helen Mirren – The Queen (speaking)

Stephanie Sawyer – Ajolidoforah (Tzipporah’s middle sister)

Linda Dee Shayne – The Queen (singing)

Francesca Marie Smith – Ephorah (Tzipporah’s eldest sister)

Brian Stokes Mitchell – Jethro (singing)

Bobby Motown – Rameses’s Son

Michelle Pfeiffer – Tzipporah

Eden Riegel – Young Miriam

Martin Short – Huy

Patrick Stewart – Seti

Additional voices: Jack Angel, James Avery (yes, that James Avery) and Mel Brooks

Hebrew child singers: Andrew Johnson, Chris Marquette, Michel Patrician, Shira Roth, Justin Timsit

Sources of Inspiration – The Book of Exodus, the second book of the Torah and the Bible, Mosaic authorship, c. 6th-5th century BCE (approx.)

Release Dates –

December 16th, 1998 at the UCLA’s Royce Hall, in Los Angeles, California, USA (premiere)

December 18th, 1998 in USA (general release; it also opened in the UK that day)

Run-time – 99 minutes

Directors – Brenda Chapman, Steve Hickner and Simon Wells

Composers – Hans Zimmer

Worldwide Gross – $218 million

Accolades – 10 wins and 29 nominations, including an Oscar win

1998 in History

The Lunar Prospector spacecraft is launched into orbit around the Moon, providing plenty of valuable data

Ramzi Yousef is sentenced to life in prison for his part in planning the 1993 World Trade Center Bombing

In the same month, Unabomber Ted Kaczynski also gets life imprisonment

A US Marine Corps aircraft severs the cable of a cable-car near Cavalese, Italy while flying too low; twenty people are killed and both men are court-martialled and dismissed

A massacre in the town of Likoshane (then in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) begins the Kosovo War

The Galileo space probe indicates the existence of a liquid ocean beneath the ice crust on Europa, a moon of Jupiter

The theory that the universe is expanding is put forward for the first time

At the 70th Academy Awards ceremony, Titanic becomes the second film ever to win 11 Oscars (the final part of the Lord of the Rings trilogy would become the third in 2004)

The Akashi Kaikyō Bridge opens in Japan, connecting Honshu and Awaji Island; it has the longest central span of any suspension bridge in the world

The Good Friday Agreement is created, a major development in the Northern Ireland peace process

Disney’s Animal Kingdom opens at Walt Disney World in Florida

Economic problems lead to the May 1998 Riots of Indonesia, which mainly targeted Chinese people; President Suharto resigns and the government is restructured

India and Pakistan conduct nuclear testing amidst great controversy; Pakistan was the seventh nation in history to possess nuclear weapons

The Guinea-Bissau Civil War begins after former Brigadier-General Ansumane Mané seizes control over military barracks in Bissau

Microsoft releases Windows 98

Japan becomes the third nation to begin exploring outer space with the launch of a probe to Mars

The Second Congo War begins, becoming the deadliest war since World War II by its end

The US Embassies in Nairobi, Kenya and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, are bombed, killing 224 people; the events are linked to Osama bin Laden

Google, Inc. is founded in Menlo Park, California, by Stanford University PhD candidates Larry Page and Sergey Brin

The Cuban Five, a group of Cuban intelligence officers, are arrested in Miami and convicted of espionage

In Colorado, 21-year-old student Matthew Shepard is beaten, tortured and left to die in a field, succumbing to his injuries in hospital six days later; his murder brought international attention to hate crimes, especially towards LGBT+ individuals

The popular Elmo’s World segment debuts on Sesame Street

Voyager 1 overtakes Pioneer 10 as the most distant man-made object from the Solar System

A Russian Proton rocket launched from Kazakhstan carries the Zarya Module, the first piece of the International Space Station, into space

Hugo Chávez is elected President of Venezuela

US President Bill Clinton is impeached, but also acquitted, allowing him to complete his term of office

Births of Ariel Winter, Zachary Gordon, Peyton List, Elle Fanning, Atticus Shaffer, Jaden Smith, Bindi Irwin, Shawn Mendes and China Anne McClain

I am a non-religious person with very mixed feelings about both DreamWorks and Jeffrey Katzenberg, so you can imagine how it feels to name The Prince of Egypt as my favourite animated film of all time. Still, I can hardly claim otherwise – this truly is a masterpiece, so I’m being upfront from the start about my bias towards it. Considering the type of thing DreamWorks tends to put out nowadays, it can be slightly embarrassing to admit that your favourite animated film is one of theirs, but with this review I plan to justify myself. I’ve been looking forward to this one!

The story begins with Jeffrey Katzenberg (doesn’t it always). During his time at Disney, one project he’d always wanted to do was an animated reimagining of the classic fifties epic, The Ten Commandments, but his boss, Michael Eisner, had always refused. After his departure from Disney in 1994, Katzenberg got together with Amblin Entertainment founder Steven Spielberg and music producer David Geffen and set up the new studio of DreamWorks in October. During a meeting in Spielberg’s living room one day, the director himself recommended that Katzenberg take up his cherished Ten Commandments project at last and make it DreamWorks’s debut feature. That was all the encouragement Katz needed, and thus, The Prince of Egypt began its journey.

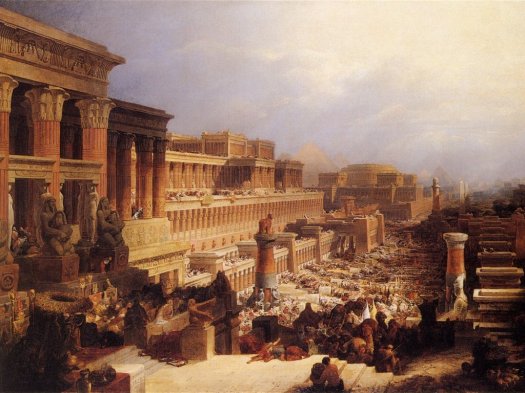

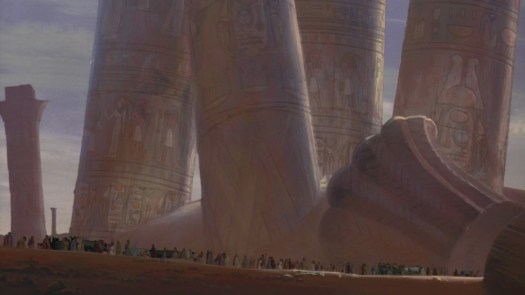

From the beginning, Katzenberg brought his considerable experience in the world of animation to the table; having observed Disney artists taking research trips to real-world locations in preparation for their films, he arranged for the DreamWorks team to take one too. In this case, that meant a two-week trip across Egypt and the Sinai before production got underway, an experience which added a great deal of authenticity to the work being produced and inspired the artists by allowing them to work en plein air in the world of their story. While there, they drew from wall paintings, statues, illuminated papyri, surviving garments and ornaments in museums and the environment itself for inspiration; no detail was overlooked.

An important decision was made early in the process, when Brenda Chapman was appointed as one of the film’s three co-directors. Katzenberg knew her well from his time at Disney, where he’d been impressed with her contributions to films like Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Lion King (1994). By taking on this role, Chapman thus became the first woman ever to co-direct an animated film from a major movie studio, more than a decade before either Disney or Pixar would see their first female directors (and when Pixar got its first, in 2012, it was once again Chapman herself in the role). The film’s two producers were also women; Penney Finkelman Cox and Sandra Robbins both came from live-action backgrounds.

Initially, the newly-assembled DreamWorks team began production on the film in an empty Burbank office building in February of 1995, but by the end of summer in 1998 as production was winding down, they had moved into a glossy new studio complex of their own in Glendale. Over the course of the project, many artists were attracted to the film by Spielberg and Katzenberg’s reputations, and a further influx of European talent came in 1997 when Spielberg’s Amblimation studio merged with DreamWorks. The departments worked more closely together and were less hierarchal than was typical for animation studios at the time (perhaps because Katzenberg had learned his lesson about executive meddling at Disney). There was a push for greater realism and maturity, an excellent decision in my opinion, because Katz wanted people to take this film more seriously instead of seeing it as a “kid’s film” simply because it was animated – with this aim, a lot of extraneous business and unnecessary comic characters were cut out to keep the story tighter.

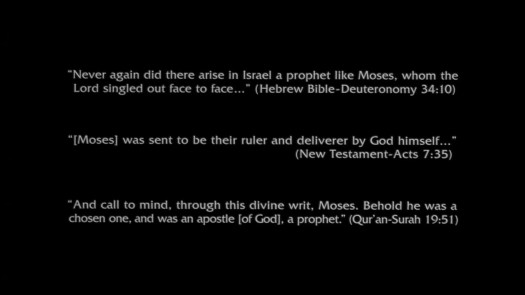

Due to the sensitive nature of this particular story, Katzenberg also called in a number of Biblical scholars, Christian, Jewish and Muslim theologians, and Arab American leaders to help keep the film as accurate and faithful as possible to its holy source material. These experts included the likes of Dr. David Polz, Everett Fox, Dr. Burton Visotsky, Rabbi Stephen Robbins and Shoshana Gershenson, all of whom can be seen listed in the credits. In addition, the team talked to Egyptologists, archaeologists and scholars to gain a better understanding of the world of Ancient Egypt. After previewing the near-finished film, these experts widely agreed that the executives had (for once) listened and responded to their ideas, praising them for reaching out to them for help in the first place. (This just goes to show what a difference accuracy can make – right, Pocahontas?)

The finished film premiered at the end of 1998 to warm reviews and excellent business, and its reputation has only grown over the two decades since. So what, exactly, makes this such a classic? Follow me back to the Bronze Age and the land of the pharaohs, and we shall see…

Characters and Vocal Performances

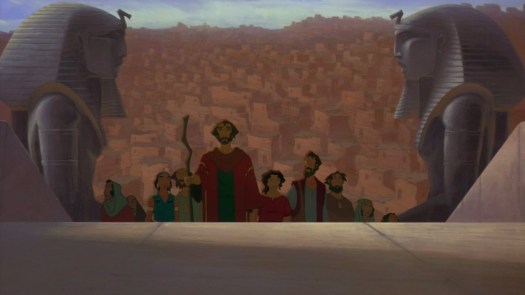

The character designers for this film were Carter Goodrich, Carlos Grangel and Nicolas Marlet, and they faced a challenge, because this cast of characters were among the most well-known on the planet. As with every other aspect of production, the aim was realism; to give the characters a more realistic feel than the usual animated ones at the time, the designers deviated from the usual “golden ratio” on their faces, elongating the midsections slightly and giving their cast a “look” distinct from the rest of animated cinema. They also worked to distinguish the more angular and symmetrical faces of the Egyptians from the rounder, softer ones of the Hebrews and Nubians, a theme carried on by the art department as a whole in the architecture and environments. Before casting, the artists created pencil tests of the characters dubbed with lines from older films by the prospective actors in order to entice them.

Naturally, one of the biggest challenges of the film was deciding how to depict God. To create His voice, Lon Bender was assigned to work with the music team who were in turn working with composer Hans Zimmer. As he explained, “The challenge with that voice was to try to evolve it into something that had not been heard before. We did a lot of research into the voices that had been used for past Hollywood movies as well as for radio shows, and we were trying to create something that had never been previously heard not only from a casting standpoint but from a voice manipulation standpoint as well. The solution was to use the voice of actor Val Kilmer to suggest the kind of voice we hear inside our own heads in our everyday lives, as opposed to the larger than life tones with which God has been endowed in prior cinematic incarnations.”

This rather Kabbalistic notion was built upon by having the rest of the cast perform God’s lines as well, with everyone whispering so as not to dominate the performance (Kilmer started out whispering too, but the team realised that they needed someone’s voice to stand out for clarity). You can still hear the cast’s whispered lines beneath Kilmer’s in the final performance. Interestingly, this was not the first time that the actor playing Moses was also given the lines of God – The Ten Commandments (1956) had Charlton Heston do the same.

Dare I write about God as a “character”? And as a darn-near atheist? Perhaps I’d better not; I could easily get into an entire discussion about depictions of God, His “personality” and my interpretations of Him, but that’s not what we’re here to talk about. Suffice it to say that while He does seem a tad temperamental in this film, He still stays with Moses throughout his ordeal and is of course the main reason the Hebrews are freed – but you don’t need me to tell you that, we all know this story. God is a special case and sort of beyond being a “character”; let’s get to the rest of the cast.

And what a glittering cast it is, too! It’s remarkably star-studded, boasting the Oscar-winning Dame Helen Mirren and Sandra Bullock and the Oscar-nominated Ralph Fiennes, Michelle Pfeiffer and Jeff Goldblum, giving even The Lion King a run for its money; that film had three Oscar winners of its own in the forms of Whoopi Goldberg, James Earl Jones and Jeremy Irons. This impressive collection was undoubtedly chosen as another of Katzenberg’s efforts to garner greater respect for the film; the nineties was when casting big-name Hollywood stars in animated films started to become common, but in this case, it’s not gratuitous at all – everybody involved delivers some top-class performances.

The only criticism I can make is that, much like the African-set Lion King, the cast are almost entirely white: with the exception of Danny Glover, there are no black, Arab or Egyptian actors in the core cast at all. Now, an argument can perhaps be made that ethnic accuracy in casting is less of an issue in the world of animation where the actors’ faces will not be seen on-screen, but at the end of the day, an opportunity is an opportunity, and it would have been the cherry on top of a beautiful cake if the cast could have been just a little more diverse.

The actors themselves, most of whom had had little prior experience with animation, alternately found voice-acting both freeing and constraining. Kilmer and Fiennes in particular went on to express regret that their schedules did not allow for them to record together, as they felt it would have helped their portrayals if they could’ve established a genuine “brotherly” bond in real life. (They did speak over the phone many times, at least). For my money, I’d say they both still did a superb job depicting the troubled relationship between their two characters, but we’ll get into that below. First, we need to talk about Moses.

In the central role, Leonardo DiCaprio was apparently considered (wish he’d do something animated, he still hasn’t), but Katzenberg chose Val Kilmer early on. He said of the actor, “Val was one of the first people cast in The Prince of Egypt. He was there every step of the way; patient, understanding, and phenomenally generous with his time.” It took at least five months to design him due to the importance of his role, both within in the film and in general culture; he also had to blend in with both the angular Egyptians who he starts out living alongside, and the softer Hebrews who he later joins (his face shape actually changes subtly).

Our Biblical protagonist, Moses, goes on quite a journey over the course of this film. Born to a slave woman, he barely escapes being killed in his infancy by the pharaoh’s soldiers, only spared because his mother bravely sets him adrift on the Nile in the hope that it will carry him to a better home. Against all odds, it does, delivering him into the arms of the very Queen herself, and so his new life as a prince of Egypt begins.

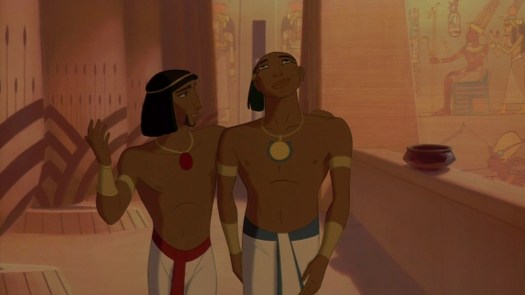

When we next see Moses, he’s a cocky young adult careening about the kingdom with his brother, causing havoc for their frustrated father. Right from the start, Moses’s portrayal is made believably human; he is as wild and reckless as any other young adult could be and is perhaps a little spoiled and mischievous like his brother. After a crazy chariot race lands them in hot water, what quickly becomes apparent in the meeting with their father, Seti, is that Moses enjoys a freer reign from his parents than Rameses does, presumably because he is not, as the second-born, in line for the throne.

We also see the difference in temperament between the two boys at this age; while Moses can get carried away by his imagination and sometimes neglects to consider the consequences of his actions, he can also recognise when his hijinks have gone too far and has the strength of character to own up to his mistakes, trying to take responsibility for his actions. Rameses, on the other hand, tries to defend himself and does not take his father’s criticism well, something Seti picks up on – he tries to make Moses into an example for Rameses to follow, which naturally irritates Rameses further.

Moses is, at heart, humbler and has a stronger moral compass than his brother, which make him a more natural leader than Rameses. Even at this age, his humility and sensitivity influence those around him for the better, calming both Seti and Rameses and negotiating a better outcome for his brother.

These traits are further evidenced at the royal banquet, where we see Moses’s best and worst sides back-to-back; after getting carried away having “fun” with Tzipporah and humiliating her, his mother’s reproachful gaze is enough to engage his conscience and he immediately sees the injustice of what he’s done. He then makes up for it by allowing her to escape from the palace, which happens before he’s had any reason to question his heritage – it is made clear that Moses was always a good person deep down, even when he is living as a spoilt prince. Rameses, on the other hand, is more like his father, failing to see non-Egyptians as fellow humans and objectifying Tzipporah completely, feeling no shame at Moses’s treatment of her and merely laughing along with everyone else.

One of the most compelling elements of Moses’s portrayal here is his dynamic, complicated relationship with his brother, something which previous adaptations of the Exodus story had never really explored. Just like real brothers, the two have conflict – Rameses in particular feels a sense of inferiority, because Moses is free from the pressure placed upon Rameses by their father and thus enjoys a more favourable standing in his eyes – but they also have fun together, and can count on each other for support when it’s needed. Of course, as the more unstable one, it is usually Rameses relying on Moses for that support; Moses understands Rameses and is able to control his emotional outbursts, calming him down and cheering him up. This relationship becomes the driving force behind much of the plot later on, so it’s important to pay attention to these early cues as they are referred to again down the line.

On the night he helps Tzipporah escape Egypt, Moses happens to run into his true brother and sister in the slave village of Goshen, although he does not know who they are at this point. Miriam, of course, knows exactly who he is (having watched the Queen find him as a child) and believes he has come to reunite with them. This scene marks the first turning point for Moses; as it begins, he is as imperious and incredulous as his brother would have been, treating Miriam harshly and calling her a slave, but that all changes when she sings their mother’s lullaby. The gentle song triggers something in Moses’s subconscious, and suddenly frightened, he sprints back to the safety of the warm, enveloping palace and the life he’s always known.

Yet he can’t shake off the feelings stirred up by the half-forgotten song, and as he drifts into an uneasy sleep, we enter the “Hieroglyphic Nightmare,” where he remembers his mother’s goodbye. After discovering a mural confirming the horrible reality of the Hebrew slaughter, Seti’s total disregard for their lives is the final straw – suddenly, Moses doesn’t recognise this man he’s called “father” and backs away in horror. Unlike the people who raised him, Moses isn’t comfortable with the idea of some lives being worth more than others (just look at how he cringes whenever Rameses starts his “I am the morning and the evening star” routine), and it is Seti’s lack of basic humanity that convinces him to abandon his adoptive family.

That’s not to say he can just leave without a struggle, though. The pain and internal conflict he goes through in deciding what to do is evident, especially in his last scene with Queen Tuya, who has been a mother to him for so many years. I’m glad scenes like that one were included, driving home the reality of how difficult this decision would actually be; people are never black-and-white, and simply renouncing the royals entirely is not that easy.

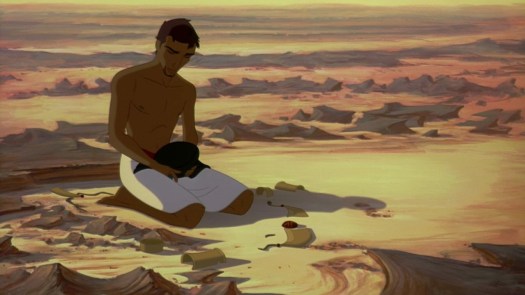

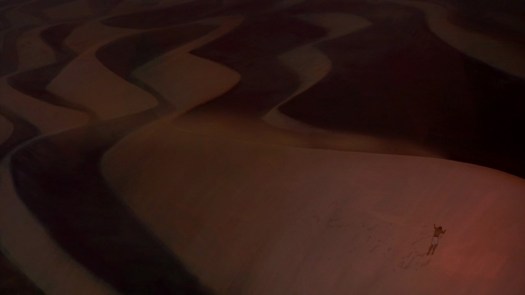

However, after accidentally killing an Egyptian overseer who was abusing an elderly slave, Moses realises he can’t stay here any longer – he can’t stand by and facilitate his family’s cruelty now that he knows the truth about his origins, so after a tragic farewell to his bewildered brother, he runs out of Egypt for good. With no apparent plan as to where to go or what to do, this could almost be read as a suicide attempt; he’s simply so disgusted with himself and the life he’s been living that he wants the ground to swallow him up (and it very nearly does).

However, even at his lowest moment, Moses is still Moses. After desperately clinging to a wandering camel’s water pouch, he is dragged to a small oasis where a pair of brigands are attempting to rob a trio of young girls. Even in his weakened state, Moses gathers the strength to stand up for them – and in typical Moses fashion, his playful method of ridding the girls of their attackers is to set loose the men’s camels, sending them running after the animals in a panic. His “moment” is then ruined as he topples into a well, but as the girls struggle to pull him out, he is suddenly reunited with Tzipporah – and she doesn’t let him off lightly, sending him plunging back into the well in a mischievous echo of what he did to her.

So comes the second big change in Moses’s character. At a dinner hosted by the girls’ father, Jethro, to thank him for saving them, Moses admits his shame over his past, but the kindly Jethro isn’t having any of that and encourages the young man to move on, pointing out that he has rescued all four of his daughters and is clearly not as rotten as he thinks he is. Moses thus starts to assimilate into Midian society and embraces a simpler life as a nomadic shepherd, even developing a relationship with Tzipporah (I know I often criticise animated films for pairing up the male and female leads, but in this case, aside from being part of the source material, they do make a good match, sharing the same passionate natures and sense of mischief). Moses soon takes to this new role and revels in both the communal spirit of the Midians and the natural freedom of the environment, finding greater comfort and happiness than he ever had in Egypt.

Of course, we all know that he isn’t left to enjoy this comfortable new life forever. In a reflection of Simba’s journey in The Lion King, Moses has forgotten his responsibility to the other Hebrew people back in Egypt, including his own siblings, so one day, the God of his ancestors appears to remind him of them. The encounter with God at the Burning Bush is a spectacular piece of character work, visibly moving and changing Moses forever – I may not be religious, but I still think this is a powerful and beautiful depiction of a spiritual encounter. That shot of Moses afterwards, breathless, trembling and yet tearful with joy always gives me chills (the good kind). The filmmakers are also careful never to let us forget that Moses is human, “just one man” as Tzipporah says; he expresses a lot of doubts about his ability to free the Hebrews from pharaoh’s tyranny and has to be half-bullied into it by God, but he finds emotional support in Tzipporah, who by this time is his wife. With the backing of the Divine and his wife at his side, Moses decides to return to his homeland at last – and he’s not leaving until every last Hebrew is free to go with him.

However, there’s a complication that Moses has not foreseen. Upon returning to Egypt after so many years, he finds not Seti on the throne, but his own brother Rameses! The two of them are amazed to see each other again and it’s yet another of the film’s high points, as the animators expertly cycle through the many complex emotions they’re both feeling. Facing his brother again after so long, with such a difficult and personal conflict between them, takes real bravery on Moses’s part. While he knows Rameses will not concede easily, he is still overjoyed to see him again and they embrace as if the many years between them had been but a day. Moses has lived on both sides and can understand both perspectives, to a certain degree, so he feels torn between his loyalty to his brother and his duty to his people.

As adults, we see how much Moses has grown and how little Rameses has changed. Moses is much calmer and less brash than his younger self, even though he does retain his fun-loving side. He attempts to reason with Rameses by trying to make him see the inherent injustice of what he’s doing, but Rameses still does not view slaves as people, merely seeing them as tools for the construction of a “greater Egypt than that of my father.” There’s a complete disconnect in the brothers’ perspectives which prevents them from seeing eye to eye and, in typical Rameses fashion, the pharaoh’s response to criticism is to double the Hebrew’s workload out of spite, asserting his dominance over Moses by force.

Outside, Moses encounters hostility from the other Hebrews which is summed up by Aaron; they view him as something of a hypocrite, remembering his former mistreatment of them alongside his “family” and accusing him of only caring because he’s been forced to accept that he’s one of them. Yet the women who know him best, Miriam and Tzipporah, know that this is not the case – the fact was that Moses was simply ignorant of the scale of the Hebrews’ suffering back then, and learning the truth about it was the main reason he chose to leave. Now that he’s had time to get over his own guilt, he’s here to help them, and he immediately sets out to prove this with actions rather than words by continuing to challenge pharaoh. Seeing him risking his life before pharaoh’s soldiers wins the Hebrews over, so although they continue to doubt Moses’s power, from that time on, they are by his side.

Moses demonstrates perseverance and faith as he continues his quest to persuade Rameses to free his people, but again, he remains very human, frequently looking just as awed and overwhelmed by the power of God as the others are, even as he wields it in his own staff. Once the Plagues kick in, we see the turmoil it’s causing Moses to have to do this to his former home and family – it’s viscerally painful to see him struggling with the burden of carrying out his awful task, and that moment where he breaks down sobbing on the steps of the temple, after seeing his brother grieving for his dead son, is almost too hard to watch. Yet Rameses tragically remains too proud even to accept Moses’s sympathy, recoiling from his brother’s attempts to reach out to him – both physically and emotionally.

Although the eventual success of freeing the Hebrews does not come without great cost, it’s still uplifting to see the slowly growing joy of Moses and his people as they finally do leave Egypt, although his relationship with Rameses “plagues” him to the end (see what I did there?). The grief-stricken pharaoh races out after the group to stop them, filled with vengeance, but with one final act of God, Moses parts the Red Sea and decides his people’s fate once and for all, getting them out of harm’s way before the Egyptian army are wiped out by the waters as they cascade back into place. Even before he turns to celebrate their escape, Moses still takes a thoughtful moment to consider his brother’s ruin, looking genuinely sorry for him – while Rameses’s love turned to hate, Moses’s merely turned to pity. Yet in spite of all personal obstacles, Moses and the Hebrews overcome it all to break away from the oppression of Egypt and find a new life in the great beyond (and let’s just assume that the next events of the story don’t occur in this version, because that would kind of kill the film’s message of hope).

You would expect this for a Biblical character, but Moses still goes through such an incredibly emotional journey over the course of this film, and I cannot thank the filmmakers enough for using animation to tell his story. The Prince of Egypt proves beyond a doubt that animation can be used to tell any kind of story, no matter how challenging, and deserves to be taken more seriously.

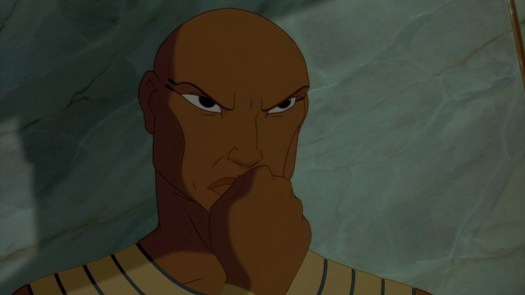

For the other central role of the film, that of Rameses II, Robert De Niro was apparently considered at one point, but they eventually settled on Ralph Fiennes – and thank goodness they did. He brings a lot of gravity and nuance to the role, even if his accent doesn’t quite align with the rest of the cast.

Rameses is the elder child in the Egyptian royal family, the next in line for the throne, and as such there is a lot of pressure on him from an early age to live up to his father’s expectations, something which leads to the development of his “fatal flaw” later on. Even when we first see him as a toddler, there is a subtle visual metaphor created with the staging; as the Queen walks on ahead holding baby Moses in her arms, little Rameses falls into Moses’s shadow below – and this feeling of being “overshadowed” by the luckier, more likeable lad continues to haunt Rameses into adulthood.

Rameses is defined by his temperament, which is stormier and fickler than his brother’s. While both are sensitive souls in different ways, Rameses pair his sensitivity with a much larger ego than his brother – a dangerous combination. As Moses himself points out, Rameses takes himself too seriously (“You care too much!”), and this frequently causes problems because of the insecurity it breeds within him. The most endearing thing about Rameses is his genuine affection for his brother, which makes it just as hard for the audience to turn against him later on as it is for Moses; in his playful interactions with his brother in their youth, we see his human side and know that there’s still a chance for his salvation, if he can only change his ways. We want to help him, because we know there’s some good in him – this is how you write a strong antagonist.

Rameses and Moses must overcome the usual brotherly obstacles, competing against each other in subtle ways for their parents’ favour and attention, but Rameses does not fail to recognise when Moses goes out of his way to help him, even recalling with nostalgia years later how he was “always there to get me out of trouble again.” While he does sometimes resent the way Moses is able to wiggle his way out of said trouble, he still relies on him for emotional support, reluctantly allowing Moses to cheer him up after some harsh words from their father have gotten him down.

Interestingly, while he looks more like his mother, Rameses seems to take after his father Seti in personality. One must assume the two of them spend a lot of time together, but Seti’s overbearing parenting style leaves Rameses with a huge knot of insecurities that affect his decisions. He is more reactive and defensive than Moses, getting hung up on his father’s criticisms and taking them to heart. As we see later, he also tends to hold grudges, remembering the details of trivial teenage pranks years after the fact. On the other hand, he can also be incredibly magnanimous when he wants to be, casually pardoning his brother of all crimes (including manslaughter, let’s remember) in his joy at simply discovering he’s still alive.

If only Moses’s influence had been able to trump that of their father’s! Perhaps Moses would have done better to stick around and stay at the palace, if only to prevent the corruption of Rameses that occurs in his absence. Seti’s psychological hold over his son spells Rameses’s doom, creating a massive, festering inferiority complex within the young prince which dominates him well into adulthood.

The thing is, Rameses is highly susceptible to outside influences. He takes his father’s accusation of being the “weak link” in the chain of the dynasty to heart (and it wasn’t even a direct accusation, more of a warning), so that when he ascends to the throne himself, he puts even more strain on the slaves by forcing them to construct ever-greater monuments to himself. These statues are visibly larger than Seti’s, as though Rameses is attempting to prove his worth by eclipsing his father’s achievements; he equates personal worth with physical objects and size equals status, so his complex manifests itself physically in the overbuilt and rather barren Egypt that Moses returns to. Rameses can also be influenced to a lesser degree by his advisors, as we see when Hotep and Huy are able to convince him that Moses’s first Plague is a sham when they shabbily recreate it before him through sleight of hand.

Unfortunately, the one person who struggles to influence Rameses is the very person who he should be listening to. When reunited as adults, Rameses and Moses’s relationship is defined by a mixture of nostalgic affection and the tragedy of Rameses’s upbringing affecting his perspective; Moses was always something of a favourite, a fact that obviously did not escape Rameses’s notice as he now clearly enjoys his power over Moses as the pharaoh.

The scene where Moses explains his reasons for returning to Rameses is one of the best in the film, with some superb acting from both characters. Even after Moses’s abrupt departure and the many years with no contact, Rameses is fond enough of him to instantly forgive and forget, welcoming him back with open arms. It’s so sad to see how he gets his hopes up, thinking that Moses has come to join him in his royal court and genuinely happy to see him again, not to mention his obvious disappointment when Moses quietly reveals that his true mission puts them at odds. When Moses dares to challenge his authority, Rameses grows haughty and closed-off, and he continues to resist freeing the slaves beyond all sense and reason as his kingdom crumbles around him.

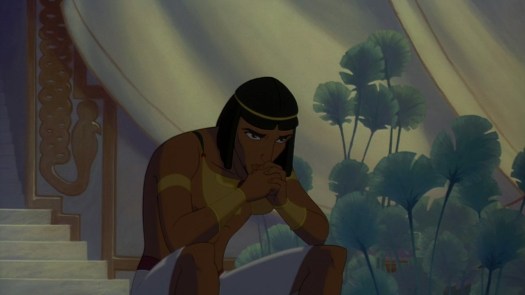

In a key scene, the men are linked visually to their shared childhood as we see Rameses brooding once again in his usual spot in the lap of a statue of his father, still feeling “overshadowed” by him and yet determined to live up to his legacy. Tellingly, it is only when Moses references a memory of a long-ago prank gone awry that Rameses begins to soften, remembering how his brother would stick up for him and expressing the last glimmer of openness to Moses’s message. This moment is so tragic, as Moses almost reaches him through their shared compassion as brothers, but unfortunately, Rameses’s son chooses this moment to come in and disrupt the mood. His fear of the Plague of Darkness hardens Rameses’s heart towards Moses again, and from this point on, he is lost, committing himself to the destructive course which will cost him everything.

Rameses is a truly fantastic antagonist (I refuse to call him a villain), because like Moses, he too is layered, complex and ultimately very human. He’s a tragic figure, potentially good at heart but corrupted by his upbringing into a powerful spoilt brat who sees himself as the centre of the universe (“I am Egypt, the morning and the evening star”). Like many spoilt children, Rameses is overly-sensitive, not easily impressed or intimidated, but also arrogant and insecure, perhaps even a little paranoid – above all else, he wants power and control, and he’s always wary of someone trying to encroach on his throne.

It’s the small moments which make Rameses’s portrayal so effective. There’s that brief, hurt look he gives as Moses sadly returns the ring Rameses gifted him in their youth, symbolising Moses’s rejection of the cruelty the ring represents (as the mark of the Royal Chief Architect, who oversaw the slaves’ work), while also representing Moses’s reluctant rejection of Rameses himself. There’s that small, warm smile that softens his face as he reminisces on his youthful escapades with Moses, wishing for a way to go back to those days with his brother by his side. And more than anything, there’s that heart-breaking, anguished look he has as he cradles the lifeless body of his young son after the final Plague, followed by that heart-stopping glare after Moses’s retreating figure.

I always end up feeling sorry for Rameses, despite the atrocities he commits, because things could have been so different if only he’d been brought up differently. From the moment we first see him as a sweet, smiling toddler in the prologue, to his last scene, all alone and screaming in fury after everything he cared about has been lost, Rameses’s journey is every bit as compelling as Moses’s and adds another layer of richness to this excellent story.

Before we move on from Rameses, let’s spend a moment on his son. This unnamed boy first appears when Moses returns to the kingdom after many years away and appears to be Rameses’s only child (a far cry from reality, where he may have had over a hundred). Even at such a tender age, the boy is already showing signs of developing his father’s arrogance, so as awful as it is, his death in the last Plague could be seen as a necessity in order to “break the chain” of the dynasty which is keeping the Hebrews oppressed. Still, that doesn’t take away from the great impact his death has, on Rameses, on Moses and on the audience – we’ve seen this child frolicking and laughing like any other in earlier scenes and it’s certainly not his fault he was born a prince. Moreover, we can feel Rameses’s love for the boy radiating through the excellent animation and vocal performance of Ralph Fiennes, so his loss drives home the crazy depths that the pharaoh’s stubbornness extends to – it takes this child’s death to finally break him, and it’s absolutely devastating.

Now we come to pharaoh Seti I, who was almost played by the likes of Ian McKellen and Jeremy Irons before the directors chose Sir Patrick Stewart. Excuse me for one moment, I just have to make a quick phone call…

Hello? Is that Chicken Little?

Yeah, hi. Could I speak to Mr. Woolensworth, please?

Alright bucko, I’ve got just one thing to say to you. When you’re casting for an animated film, THIS is how you use Patrick, freaking, Stewart!

And don’t even mention that bloody “Poop Daddy” monstrosity to me, got it?

Ahem. In all seriousness, it’s so refreshing to see an actor of Stewart’s calibre (he was trained by the Royal Shakespeare Company) playing a character befitting his talents. Seti is presented as a similarly complex character as his sons, with his first scene making him appear stern, powerful and rather remote, holding formal meetings with his sons and generally talking to them more like employees than relatives. However, Moses is able to draw out his more human side and encourages him to go easier on Rameses following their “misadventure” with the temple, so Seti decides to appoint Rameses Prince Regent. This is a remarkably generous gesture in some ways, as it effectively means he is handing over power to Rameses, although one can assume that Seti still pulled a lot of the strings while he remained alive and the move is thus more of an “on-the-job” training method. As he begins to put more responsibility on Rameses’s shoulders to prepare him for the task of becoming pharaoh, we can relate to his frustrations over his sons’ recklessness, since on the most basic level he’s just trying to make them into responsible adults.

While he does care about his sons, however, the darkness of this character cannot be overlooked. After all, he is the one who orders the slaughter of an entire generation of Hebrew boys simply because he feels threatened by their numbers (and the fact that he fears them “rising against us” at all implies a certain level of awareness of the inherent cruelty of what he’s doing). When he reveals to Moses later on that he does not even view them as real people – “They were only slaves” – we are as repulsed as Moses is by his lack of remorse for the genocide he committed. Perhaps the scariest thing about him is that he doesn’t see anything wrong in what he’s done; he does not try to hide it from Moses and even tries to reassure him with the reminder that they were “only” slaves, assuming Moses also believes them to be “lesser”.

It’s also thanks to Seti’s overbearing pressure on Rameses that the latter turns out so twisted in the end. His harsh words and high expectations haunt Rameses for the rest of his life, even long after Seti himself has “passed into the next world”, and Rameses shows signs of continuing this cycle with his own son. While Seti does get a few moments of warmth to make him more relatable, mainly involving his interactions with Moses, his actions are so despicable that I’d argue he makes for a truer “villain” in this film than Rameses does. A frightening character on a number of levels, but another very effective one.

Helen Mirren took on the role of Seti’s wife, Queen Tuya, and she greatly enjoyed the character and her design, which was partly based on an ancient sarcophagus. Dave Brewster, her supervising animator, sadly lost his own mother shortly before beginning to work on the Queen, so he incorporated a lot of his mother’s mannerisms into her acting, such as her habit of touching Moses when she speaks with him.

Queen Tuya has a very different personality than her husband’s, portrayed as much quieter and calmer. She is not even officially named in-movie, with historical records being the only clue as to which Queen she must be. Yet she is the glue that holds this family together and gets many moments to showcase her understanding of them all, guiding them through difficult events and “keeping up appearances”. In her very first scene, we see Tuya’s compassionate side as she rescues Moses from the Nile – one thing I always wonder about is whether she is aware of the genocide her husband’s men are committing that day, because if she is, her choice to keep Moses takes on even greater poignancy, representing a kind of solidarity between mothers. If she knows about the atrocity then she knows full well where Moses has come from, and by saving this one Hebrew child, she could be acting in defiance of her husband’s cruelty – but that’s just one interpretation.

In keeping with the film’s style of acting, Tuya’s personality is expressed in the smallest gestures and expressions; I particularly like that moment where her handmaidens are gawping at her as she carries little Moses up the steps and she shoots them each an imperious glare, leaving them in no doubt as to who is in charge. She is the Queen, and she carries herself with all the regal grace and poise you’d expect of one.

As her sons grow, she learns how best to handle each one, supporting the emotionally fragile Rameses as he weathers his father’s lectures and gently chiding the boisterous Moses when he’s stepping out of line. Tuya is all about subtlety; look at the way she skilfully covers her sons’ late arrival to the banquet with a hug, or her silent cues to Rameses during the meeting with Seti which prevent him from getting himself into even more trouble.

Her relationship with Moses is a close one, which makes it all the harder for Moses to end it with his departure from Egypt. She knows him well and sees that he has a better nature than he realises, holding him to a high standard – her shame when Moses humiliates Tzipporah at the banquet is enough to make the prince feel guilty, and she makes her love for him clear when he expresses doubts about his sovereignty. I like that she treats Moses exactly the same as Rameses, offering both love and guidance to each in equal measure; she’s a great example of an adoptive parent in animation. Unlike Seti, she does not view Moses as a “prince of Egypt” – to her, he is simply her son, and she loves him no matter where he came from.

One wonders what happened to she and Seti in the intervening years. Moses doesn’t seem to have been away all that long in this version, as he’s still fairly young upon his return (forty-ish would be credible) and Tzipporah’s youngest sister is still a child when they leave. Despite this, both Tuya and Seti are nowhere to be seen, having apparently passed away. Of course, Tuya seems quite a bit younger than Seti, so perhaps she is not dead but simply isn’t shown after Moses’s return because she isn’t relevant to the plot any more.

The relationship between Moses and Rameses is not the only sibling dynamic explored in this film. We also have his biological siblings, Aaron and Miriam, who were Yocheved’s first two children before Moses. Aaron was almost played by such different actors as Michael J. Fox and Scott Bakula, but was eventually cast with Jeff Goldblum, who brought to the project one of the most distinctive voices in the entire cast.

Aaron’s character as presented here might not be Biblically accurate, but his journey from incredulity and mistrust to having full faith in Moses puts a face on the journey of the Hebrew people. Aaron could be described as the realist to Miriam’s optimist; when he first reunites with Moses in young adulthood, he is fearful and subservient, recognising the danger the prince poses while Miriam desperately tries to force Moses to accept the truth of his heritage. He is careful, watchful and rather introverted, keeping to the background when he can and trying frantically to drag Miriam out of harm’s way before she can incite the prince’s wrath. Yet even in this position of total helplessness, he does what he can to protect his sister, speaking out on her behalf while still being careful not to offend “his highness”.

Years later, when an older Moses has returned to free the Hebrews, one of the first he meets outside the palace is Aaron. His brother bitterly lectures him, no doubt remembering Moses’s harsh treatment of Miriam when she first tried to reveal his identity to him, as well as his presumed ignorance of their plight when he was living as a prince. He voices the frustrations of the Hebrews at Moses having gotten their workload doubled and accuses him of being a hypocrite, only caring about “slaves” because he found out he was one. While Miriam scolds Aaron for being hard on Moses, I think he is justified to a certain extent; it may not have been entirely Moses’s fault and he was never as arrogant as Rameses, but he still did hurt Miriam, and it’s understandable that the Hebrews would hold some anger towards Moses given his former status as “their enemy”. Aaron is not being cruel; he’s just mistrustful, and who can blame him? After a lifetime of being treated like dirt, he’s bound to have his reservations. Unlike Miriam, he isn’t just going to take Moses back like that – Moses will have to earn Aaron’s respect.

Moses duly fulfils his promise to the Hebrews, doggedly pursuing Rameses at great personal risk to himself in his attempt to free them. After publicly demonstrating the first Plague with his staff, Moses convinces Aaron and the other Hebrews that his claims of wielding God’s power are the truth. However, while they now trust him, Aaron speaks for most of them when he continues to doubt Moses’s power to overcome the pharaoh.

Eventually, after the Plagues have reduced Egypt to a ruin and Moses himself has gone through a great deal of pain, Aaron and the others are won over completely and remain firmly on Moses’s side from then on. It might be tough to gain his full trust, but once Moses has it, he can rely on Aaron for anything; just look at the way Aaron has a bag packed and ready when Moses confirms that they have permission to leave at last – he may still be cautious as ever, but he truly believed Moses could do it. By the time they reach the Red Sea, Aaron has become Moses’s staunchest supporter and is the first to brave the towering cliffs of water, inviting the others to follow him with a trusting smile.

In Aaron, the general attitude of the Hebrew people and the general theme of the film – belief – are neatly summed up and personified for the audience. He’s shy, awkward and protective and I really like the dynamic he has with his sister, as well as the one he develops with his brother towards the end.

To play Aaron and Moses’s sister, Miriam, Mary McDonnell and Ellen DeGeneres were considered before the team selected Sandra Bullock. Miriam is Yocheved’s oldest child and plays a key role in the plot, as she is the only one to witness what happens to Moses after their mother releases him in his basket. This altruism defines Miriam’s character, making her one of the most likeable personalities in the film. With the kind of single-minded attachment only a child can have, she follows the basket bearing her baby brother all the way down the banks of the Nile, watching in terror as it’s nearly devoured, crushed and sunk by various obstacles until it miraculously drifts into the palace’s water garden. Seeing the Queen, the poor girl is terrified lest the royal kill the baby, but luckily Queen Tuya is not as ruthless as her husband and is immediately smitten when she sees Moses’s little face. Thus assured of her brother’s safety, Miriam sings a short lullaby of her own in which she prays for him to “come and deliver” the rest of the Hebrews one day – it is an idea she never once loses faith in as the years go by.

One night in her young adulthood, after sending a stranger on her way with some water, Miriam and her brother suddenly encounter Moses himself. Not expecting to see him, she assumes he can only have come because he’s learned the truth about his past, only to be disappointed when she realises he has no idea and still thinks of her and Aaron as mere slaves. Thinking quickly, she changes tack and takes the opportunity to tell him herself, fighting her petrified brother in her effort to make Moses understand, but the prince reacts only with anger and prepares to storm off to arrange her punishment. Before he leaves, she tries one more thing – hesitantly, scarcely believing this will work, she begins to sing the same lullaby their mother sang to Moses before she let him go. The melody triggers something in the prince’s memory, and Miriam smiles, knowing she’s gotten through to him at last.

Her actions are a catalyst that spark the rest of the plot, as she sews the seeds of doubt in Moses’s mind which cause him to finally reject his royal identity. I admire her strength of character, daring to speak out even at the risk of her own safety – you can tell she and Moses are related. Although she doesn’t get to join Moses right away after the incident with the Egyptian overseer, she remains faithful to him once he returns and is, indeed, the only welcoming face he encounters among the Hebrews at first.

Optimistic and hopeful, Miriam is a real breath of fresh air in what is often quite a “heavy” film, always staying positive and encouraging. Even when Moses himself grows sceptical, even after he’s accidentally killed someone, her first reaction is always to go to him and try to comfort him. When he gets the slaves’ workload doubled, she is not angry but understanding, because she knows and trusts what he’s trying to do, forgiving him for all past transgressions and choosing to support him in his mission to end the oppression.

The bond that develops between Miriam and Moses is beautiful, beginning in their childhood as she gazes with a maturity beyond her years upon the smiling face of her baby brother, and culminating in that final tender embrace in their adulthood, with Moses thanking her sincerely for being on his side. Although I’ve never had a sibling of my own, I wish I could’ve had one like Miriam; she’s a wonderful sister and another excellent member of this film’s cast.

In the entirely-sung role of Yocheved, the mother of Moses, Aaron and Miriam, Israeli artist Ofra Haza was cast. The woman was truly a wonder, performing her character’s part not only in English but in about sixteen more of the twenty-something languages into which the film was dubbed, pronouncing the words of the languages she did not speak phonetically. She also performed her famous lullaby while cradling a baby doll, in order to get as much genuine emotion into the performance as she could. Yocheved’s design was inspired in part by the Mona Lisa (1503), but personally, I can also see quite a bit of the Afghan Girl (1985), Sharbat Gula, in there as well.

Yocheved may not have a great deal of screen time, but my goodness, she certainly makes an impact in the scenes she does have. This woman is brave, so very brave – the horror of her situation is unthinkable, and yet it’s happening in places like Sudan, Syria and Myanmar to this day, even as I write this. Faced with the possibility of losing her precious children to the brutality of the pharaoh’s soldiers, she risks her own safety to smuggle the youngest to freedom, placing him inside of a simple basket and setting him adrift on the Nile. As we soon see, it’s a dangerous place, but the awful reality is that Moses still has a better chance of survival on its waters than he does in his own home. For any mothers watching this film, you will undoubtedly be able to feel Yocheved’s heart-break to your very core; the idea of being forced to give up your precious baby is horrendous, yet Yocheved does it to save Moses’s life, putting his safety above all else.

Aaron may represent the mental journey the Hebrews go through in this story, but Yocheved represents the collective emotional weight of their suffering. It’s a mark of the strength of the characterisation in this film that such a seemingly minor character can be so endlessly fascinating; I only wish she had more scenes. I long to know what she’s been through, and what happened to her after that day that she set Moses adrift. Personally, I like to imagine that she is somewhere among the freed Hebrews at the end, and that she and Moses were eventually reunited (after all, she could feasibly still be alive at about sixty or seventy). And yes, I know I could look to the Bible for a fuller account of her, but the versions of the characters depicted here are not always strictly accurate, even while they do get a lot right.

To finish off the list of strong female characters in this film, we have Tzipporah, the daughter of the High Priest of Midian. Apparently, Jennifer Aniston was considered for this role (that might have worked, given her strong performance in The Iron Giant around the same time), but the role ultimately went to Michelle Pfeiffer.

Tzipporah is first introduced in just about the most demeaning position imaginable; she is presented to the young princes at a royal banquet by Hotep and Huy as an “offering” to celebrate Rameses’s appointment as Prince Regent. Presumably, she is intended as a bride (or a concubine), but she is having none of it and fiercely speaks up for herself, holding herself with a commanding dignity and even insulting the princes to their faces, much to the shock of the royal court. Rameses, of course, doesn’t care for such headstrong women and so tries to “give” her to Moses, who proves a better match for her even at this unpleasant stage and gives her a run for her money, using his mischievous side to get the better of her by sending her tumbling into an ornamental pond. However, the look of furious embarrassment she gives him, coupled with Tuya turning away in shame, provoke great guilt in Moses and he thus goes to try and apologise… only to find that Tzipporah is two steps ahead and has already disabled her guard to escape the bedroom.

At this point, Moses redeems himself somewhat in her eyes by helping her sneak out, distracting the guards even when he’s plainly spotted her. This moment likely plays a part in her decision to join Moses on his quest to free the Hebrews later on, as she knows that he was always open to the idea of granting freedom to the oppressed even when he was still a prince of Egypt – her faith in his character is born in this moment and remains constant from then on.

Of course, that’s not to say she lets him off the hook entirely. When they next meet, a few days or weeks later, Moses has just rescued her younger sisters from brigands and fallen into a well. Before she realises who he is, we get a glimpse of Tzipporah’s kind, helpful nature as she immediately hurries to his aid, believing him to be some random stranger. However, when she recognises the prince who humiliated her, she playfully gets her own back by dumping him back down the well – it’s a great little character moment which establishes her self-confidence and the mischievous streak which she shares with Moses.

As Moses begins to settle into his new life in Midian, Tzipporah finds herself developing a growing attraction to him; it turns out, without the pomp and arrogance of royalty, they’re actually pretty compatible. Seeing him embrace his inner compassion and enjoying the simplicity of the life she’s always known awakens a natural feeling of kinship within her, and we see how her perspective on him changes in small moments like that one where, just as Moses leaves her in charge of the flock he’s been watching, she pulls up his staff and is surprised to find a small sprig of flowers attached to it. His growing appreciation for the beauty of nature is one of the many things she comes to love about him, and eventually, the two decide to get married (much to her father’s delight).

One day, Tzipporah’s husband comes rushing in all worked up, telling her he’s had an encounter with God and that He has told him to return to Egypt to free the Hebrews from bondage. Naturally, it’s a lot to take in and she has to sit down, but as she begins to accept the idea, she can’t help doubting Moses’s ability to pull this off – he is, after all, “just one man.” To convince her, Moses compares the plight of the Hebrews to that of her family, knowing just how to get her on board with the whole thing. He only wants for his people what her family already enjoy – “Look at your family. They are free. They have a future. They have hopes and dreams… and the promise of a life with dignity.”

Tzipporah does accompany Moses on his journey back to Egypt and remains by his side throughout, defending him from the wrath of the slaves and quickly befriending Aaron and Miriam. More than his wife, she is also his most faithful friend, knowing him better than anyone else does, and at the very end, she is given that moment where she drives home the significance of what Moses has achieved by echoing his own words to her – “Look at your people, Moses. They are free.” The look of burning pride on her face as she says it speaks volumes about how far their relationship has come from the day they first met, with her a hostage and him a “pampered palace brat”.

What a fantastic female lead Tzipporah is. She’s strong, proud and resourceful with a spirited personality, and there’s a fierceness in her eyes that commands respect from all, even the spoilt Egyptian princes. It’s worth noting that she is able to make Moses feel shame for his treatment of her even before he has begun to question his royal standing; this woman can bring rulers to their knees with just her eyes. Her character symbolises a reconciliation between Moses’s past and present, as her forgiveness of his princely arrogance (and her blossoming friendship with her sister-in-law, Miriam) is partly what allows him to move on and grow beyond his old identity. I know I’ve said it about every single character so far, but Tzipporah brings a lot to the story and I enjoy her immensely every time I watch.

Tzipporah’s father, Jethro, was considered for Keith David, Vernon Wells and James Earl Jones before Danny Glover was cast, and his portrayal was inspired by the likes of Anthony Quinn in Zorba the Greek (1964) and Luciano Pavarotti. He is another one-scene wonder, first introduced after Moses arrives in Midian and spending much of his screen time singing about how Moses needs to forgive himself for his past and embrace his future. He’s a great big bear of a man, warm and welcoming, accepting Moses into his community with no reservations; while he knows from Tzipporah that Moses has done things he regrets, he encourages Moses rather than ostracising him and teaches him the value of a simpler, nomadic life. Jethro seems to be a good judge of character and, much like Tuya, knows that Moses is kinder than he sometimes appears; he even performs the wedding ceremony at which his eldest daughter takes Moses’s hand in marriage. As far as fathers-in-law go, I’m sure Moses couldn’t do much better than this.

Interestingly, despite his apparently advanced age, Jethro also has three younger daughters, the smallest of whom looks to be scarcely five years old at most. These girls are named Ephorah (the eldest), Ajolidoforah (middle) and Jethrodiadah (the youngest) and are the first Midians Moses meets after his wanderings in the desert. (Fun fact: In the Bible, Tzipporah actually had three more younger sisters). If helping Tzipporah to escape Egypt wasn’t enough, Moses sets the tone for his future with these people by rescuing the girls from brigands as his first act, even if he does spoil the effect slightly by falling into a well. These three characters may only play very minor roles, but they’re still given enough attention to feel like real people – if you pay attention, you’ll notice that the two youngest girls look to Ephorah for “wisdom” just as any younger siblings would, and while Ajolidoforah seems to be in her “boy-hating” phase and doesn’t take to Moses right away, little Jethrodiadah is all over him, inviting him to sit with her at the feast and enjoying silly games with him in a montage.

It is the familial bond between Jethro and his family which inspires Tzipporah to join Moses, so they can bring the same freedom to the Hebrews. The ages of the three younger sisters also serve as a rough marker of the passage of time, as we can see when Moses and Tzipporah leave that they have all aged; Ephorah and Ajolidoforah are now young women, while Jethrodiadah seems to be in her early teens, implying the passage of about a decade.

Ah. Now. I’ve saved these two for last because, unfortunately, I find them to be the “weak links” in this film’s cast. The priests Hotep and Huy were almost voiced by performers such as Richard Schiff and Tom Waits, as well as Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong, but finally, the friends and frequent collaborators Martin Short and Steve Martin (a bizarre coincidence of naming) took on the roles. They benefited from being able to record much of their dialogue together, an opportunity I only wish Kilmer and Fiennes had been able to take advantage of.

It’s hard to admit after heaping so much praise on the rest of the characters, but it has to be said – Hotep and Huy are the weakest ones on offer here. They function as minor antagonists who are often the victim of the young princes’ pranks in their youth, as they are presented as being pious to the point of superstition and are easily disturbed by the princes’ “blasphemy”. In addition, they also offer some comic relief, which is admittedly appreciated some of the time in such a dark film.

The pair somehow outlive both Seti and Tuya and remain in their positions into Rameses’s reign, perhaps a sign of their insidious hold over the ruling class (they also seem not to have aged a day since Moses left). As Moses begins to demonstrate the power of God before the sceptical Egyptians, Hotep and Huy try with increasing desperation to top the Almighty with their shady tricks, but their “skills” are no match for His wonders and they are soon suffering under the effects of the Plagues like everyone else. The last we see of them, they’re covered in some painful-looking boils and are attempting to treat them until an angry Rameses overturns their table and sends them packing. Presumably, they wound up either banished or dead, no longer able to maintain their position in the royal court in the face of such powerful opposition.

While Hotep and Huy don’t add much to the cast and their cartoony designs stick out a bit, I can’t be too hard on them since they’re only here to lighten the mood. It’s not quite as bad as the infamous Hunchback gargoyles as they do, at least, feel like a more organic part of this world than those abominations did, but for me, they are still among the film’s few weak aspects.

Animation

The Prince of Egypt features a blend of traditional animation supported by computer animation, as did many other big-budget projects of the 1990s. The main software used to create the film were Toon Boom Animation and Silicon Graphics, with 3D layout artist Harald Kraut incorporating lighting into the texture maps that were then applied to 3D surfaces to help the computerised elements better blend with the hand-drawn ones. The characters themselves were digitally inked and painted in Cambridge Systems’ Animo software system (which has since merged with Toon Boom) and the 2D and 3D elements were combined using the newly-developed “Exposure Tool,” which was created especially for DreamWorks by Dylan Kohler of Silicon Graphics. The team also used Renderman shaders and Dynamation for the water effects.

Right from the beginning, the scale of this project was enormous, involving over four hundred artists and technicians from thirty-eight countries. Many of the artists were recruited by Katzenberg from Disney and later from Amblimation, which, as I mentioned in my intro, was merged with DreamWorks in 1997. Just as they had at Disney, the animators were grouped into teams assigned to specific characters, with supervisors who would set the acting style of that character for the others to follow; the designers were also careful to depict the ethnicities of the Egyptians, Hebrews and Nubians properly, distinguishing the groups subtly by colour and face shape.

The supervisors on this film included Kristoff Serrand, who handled Older Moses and Seti, William Salazar, who did Younger Moses, David Brewster, who did Older Rameses and Queen Tuya, Serguei Kouchnerov, who did Younger Rameses, Rodolphe Guenoden, who did both Tzipporah and Yocheved, Gary Perkovac, who did Jethro, Patrick Mate, who did Hotep and Huy, Bob Scott, who did Miriam, Fabio Lignini, who did Aaron, Rick Farmiloe, who did the camel, and Jurgen Gross, who did the horses. Final line animation was handled by Brett Newton in clean-up. As I’ve mentioned above, the artists strove for realism in their work, keeping the acting restrained in comparison to the more typical exaggerated pantomime of many animated films and drawing upon the performances of the voice actors for inspiration, even hiring David and Dorite Dassa (children of the famous Israeli folk dance artist Dani Dassa) to choreograph moments like the folk dances we see in Midian.

The style works wonders, expressing a great deal more emotion than you often see in animated characters, but what I really love are the small hints of personality that are expressed in minute gestures – for instance, you’ll notice that Rameses has a habit of throwing his hands down in frustration, and when seated, he tends to rest one arm on his knee or chair arm. Moses, meanwhile, is clumsy, and Tuya tends to hold her hands clasped in front of her when not using them. The character work is filled with little details like these which add so much to the overall effect. For me, one of my favourite parts animation-wise is the meeting between the adult Moses and Rameses in the throne room, in which the depth and complexity of their relationship is fully expressed with a whole range of delicate expressions – scenes like this one are why animation deserves more respect.

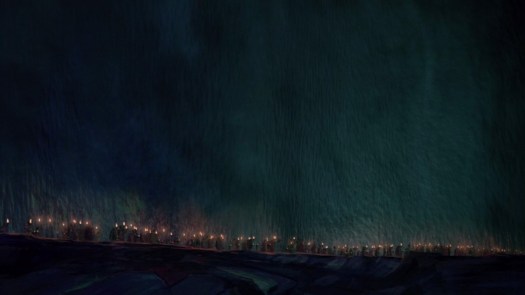

Of course, there’s more to The Prince of Egypt’s animation than just its characters. There are over a thousand individual scenes in the film, the vast majority of which contain special effects work involving everything from blowing wind and dust to rainwater and shadows; basically, anything that moves and is not a character. The blend of traditional and computer is shown off to its best effect in the depiction of the Ten Plagues of Egypt and in the parting of the Red Sea – the former sequence featured up to seven million locusts in some shots, with a particle system used to achieve the effect of blood filtering through the water of the Nile, while the latter sequence required a team of ten people (led by Henry LaBounta) and took two years to create, layering the effects on little by little to make the film’s pièce de résistance.

For the most part, the animation has held up beautifully, especially for a twenty-year-old film. DreamWorks’s other release from that year, the fully computer-animated Antz, is looking pretty dated from today’s perspective. Although there are a few isolated elements which haven’t held up – the infamous nose falling off the statue during the chariot race comes to mind – there’s nothing that seriously detracts from the film’s overall spectacle and it’s just as lush and gorgeous as it was two decades ago.

Plot

Considering the fact that this film’s plot is an adaptation of a Biblical story, the writers were aware from the start of how careful they’d have to be not to step on any toes. This is precisely why they consulted with so many religious experts, working hard to ensure as much accuracy and sensitivity as possible – the film even opens with a tactful disclaimer: “The motion picture you are about to see is an adaptation of the Exodus story. While artistic and historical license has been taken, we believe that this film is true to the essence, values and integrity of a story that is a cornerstone of faith for millions of people worldwide. The biblical story of Moses can be found in the book of Exodus.”

The process of writing the film was ongoing throughout the production, with story supervisors Kelly Asbury and Lorna Cook starting out with a rough outline and leading a team of fourteen storyboard artists and writers, who began to sketch out the film more fully. Phil LaZebnik was the lead writer in this team, and it also included Tom Sito, who was a visitor here not too long ago (if you’re reading this Mr. Sito, congratulations on being a part of this masterpiece). The storyboarding process extended over more than two years; once a board was approved, it would be put into an Avid Media Composer digital editing system by editor Nick Fletcher, in order to create an animatic which combined the boards with scratch dialogue and music. (“Scratch” dialogue is stand-in work used before the actors are cast; Brenda Chapman’s version of Miriam’s lullaby started out like this, but was good enough that they kept it in). Having a “story reel” gave the team greater flexibility in editing and adapting their story before it went into full animation, as well as helping the layout department get a feel for how to stage each scene. As the Black Cauldron team tried to warn Katzenberg years before, editing animated films after they’ve been animated is notoriously difficult and expensive.

Director Steve Hickner made a significant addition in October of 1997, when he suggested a more hopeful and uplifting ending – until then, the film was supposed to end with the waters of the Red Sea crushing the Egyptian army, which was rather bleak. Hickner gave Tzipporah that key moment where she reminds Moses what he’s worked and sacrificed for by telling him to look at his newly-freed people. This makes it clearer to the audience that Moses has achieved his mission, despite losing his relationship with Rameses; I suppose given that it’s a family film, they needed a way of making the ending feel “happier” and it works nicely, giving the climax a real sense of triumph. That’s not to say that the film tries to soften the source material; it doesn’t shy away from depicting the brutal reality of slavery, with lingering shots of whip-scarred slaves and haunting close-ups of their tortured, angry eyes – I applaud it for tackling the material maturely. It’s rare I say this, but for once, Katzenberg’s vision was right on the money.

Of course, as with almost every film adaptation of literature, a few changes had to be made to make the story more suitable for general audiences, or for narrative purposes. Among the differences between the film’s story and the Biblical account of Exodus are the following;

1. Moses was actually adopted by pharaoh’s daughter, not his wife (the woman is alternately known as Thermuthis, Bithiah, Merris, Merrhoe, Scota or Asiya depending on faith)

2. The death of the Egyptian overseer was no accident in the original story and Moses even tried to hide the man’s body; clearly deliberate murder wouldn’t suit a modern hero

3. Aaron was far more supportive of Moses from the beginning and acted as public speaker for him, since the Biblical Moses had a stutter

4. Aaron was also the one who turned his staff into a snake before the pharaoh and executed the first three Plagues

5. Moses’s age is greatly reduced here, with many of the events condensed for the sake of a reasonable running time; originally, the incident with the Egyptian overseer occurred when he was about forty, and he was pushing eighty when he returned to confront the pharaoh (he also lived to be one-hundred-and-twenty, not uncommon for Biblical figures)

These are just a few of the most notable changes. It’s also worth noting that things take a more unpleasant turn after the credits roll; the filmmakers were wise to end their story when they did. While the film-Moses is implied to be introducing the Hebrews to his comfortable nomadic life near Midian, the Biblical one grew angry with them after the whole “worshipping a golden calf” problem and pronounced them unworthy of inheriting the “promised land” of Canaan. Although their descendants, the Israelites, did eventually get there, Moses himself died beforehand and their entry into Canaan was not peaceful, described as a “conquest” involving battles in which they were aided by their God (called Yahweh in the original).

There’s also the question of historical accuracy, since many of the figures portrayed were real people. I’m not going to get into the whole debate about whether Moses was a real person, but we know the Ancient Egyptians were, at the very least. Pharaoh Memaatre Seti I was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt’s New Kingdom period, reigning from approximately 1290 to 1279 BCE. In addition to Rameses II, he also had at least two other children, perhaps three: Tia, Nebchasetnebet and Henutmire, the latter of whom may otherwise have been Rameses’s daughter. In keeping with what happens in the film, there’s little evidence to support the idea of a coregency between he and Rameses – the young prince was merely appointed Prince Regent (at about the age of fourteen, rather than twenty-ish like in the film) until after his father’s death (which is estimated to have been around the age of forty), and he did indeed continue to build and enhance many of his father’s unfinished temples. Seti is not widely believed by scholars to be the pharaoh of the events in Exodus; more popular candidates include Ahmose I, or Thutmose II of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Rameses himself, meanwhile, reigned from c. 1279 to 1213 BCE and lived to an impressive 90-91 years of age. His reign was considered one of the greatest in Egyptian history alongside those of Thutmose III, Tutankhamun and Cleopatra VII Philopator, with some calling him “Rameses the Great” (bet the film-Rameses would love that) and the Greeks dubbing him Ozymandias, later inspiring Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1818 poem of the same name after Giovanni Battista Belzoni removed a seven-ton statue of him from the Ramesseum and sent it to the British Museum. Incredibly, Rameses may have had over a hundred children to eight different wives (certainly over eighty, at least), but the one depicted in the film is presumably Amun-her-khepeshef, his firstborn.

Cinematography

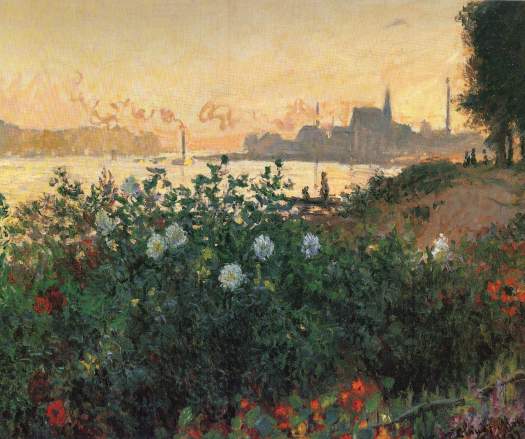

This leads us nicely into the section I’ve been looking forward to the most: cinematography. The film’s art directors, Kathy Altieri and Richard Chavez, background supervisors Paul Lasaine and Ron Lukas and production designer Darek Gogol all worked together to lead their respective teams in the depiction of the grandeur and majesty of Ancient Egypt. The finished film contains over nine hundred individually hand-painted backgrounds, which were inspired by a wide variety of sources ranging from John Singer Sergeant and Alphonse Mucha to Joaquín Sorolla, Anders Zorn and Thomas Moran. Artists also studied the lithographs of David Roberts at the Huntingdon Gallery in San Marino, California, and there are shades of Disney’s Fantasia at times in the impressionistic backgrounds (the Red Sea procession in particular resembles the pilgrims from the Ave Maria segment). Stylistically, the work in the film displays influences from a whole plethora of different art styles such as art nouveau, film noir and Russian Impressionism.

However, the film’s core aesthetic drew upon three key sources – illustrations of Gustave Doré, the art of Claude Monet and the cinematography of David Lean. How very grand! Of course, the Cecil B. De Mille epic The Ten Commandments (1956) was an ever-present spectre in the artists’ minds, as they knew their film would be compared to it. All of these magnificent sources make their influence known, as the film is among the most stunning to ever grace the big screen. Just look at it…