OPENDOORSREVIEW

AnArt&Literary MagazineinItaly

June2023N.4

The Open Doors Review N. 4

An Art & Literary Magazine in Italy in English & Italian

Website www.opendoorsreview.com

Email Contact@opendoorsreview.com

Podcast Open Doors Review Podcast

Facebook Open Doors Review

Instagram @opendoorsreview

Staff Lauren T. Mouat, Monica Sharp, Nora Studholme, Norah Leibow, Michela Guida

Cover Image Tralici by Valerio Arena

© Open Doors Review, June 2023 Issue.

All authors and artists retain the copyrights to their respective works.

2

OpEn Doors MAnifEsto

In popular culture, Italy is frequently seen as two things: a soap opera Mafiosi video game or a picture postcard tourist dreamland of the Dolce Vita.

Let’s add more stories to this picture. Let’s look under the surface. Let’s highlight the creativity and skill of the people in Italy. Now. Today. The point is not to produce something Italy-focused. It’s to create a collection of writing and visual art that is Italy-grown.

Who do you love? What do you believe in? What do you know? These days, truth is under attack. Reality means different things to different people. While language is increasingly black and white the issues, like our hearts, never are. Art lives in these spaces between.

We are cracking open, evolving, breaking up with the old world, breaking down the new. That’s where art grows. That’s where conversations happen. There, in that space, we find our humanity when we share and connect with each other.

I challenge you to step into that place and create. Come on in, the doors are open.

Agli occhi di uno straniero, L’Italia viene spesso vista come il paese della pizza, della Mafia e della Dolce Vita.

È l’ora di condividere storie ed immagini per scardinare questa stereotipo e dare un’occhiata più nel profondo. Mettiamo in risalto la creatività e l’abilità delle persone del “Bel Paese.” Adesso. Oggi. L’obiettivo non è di creare qualcosa che sia incentrato solo sull’Italia. Si tratta di diffondere una raccolta di scritture ed arti visive cresciuta in questo posto.

Chi ami? In che cosa credi? Cosa è reale? In questi giorni la verità è in pericolo. La realtà viene percepita in maniera diverse a seconda del punto di vista delle persone. Mentre il linguaggio è sempre più categorico, i problemi (come i nostri cuori) non lo sono. L’arte fiorisce proprio in questo terreno di mezzo.

Ci stiamo aprendo. Ci stiamo evolvendo. Stiamo rompendo con il vecchio mondo e mettendo il nuovo alla prova. È qui che avvengono le conversazioni. È così che cresce l’arte. Qui, in questo spazio, condividendo e connettendoci l’uno con l’altro, ritroviamo la nostra umanità.

Non ti resta che entrare in questo luogo e iniziare a creare. Le porte sono aperte.

3

ContEnts

3

Open Doors Manifesto

6 Letter From the Editor

8 Interview with Author & Guest Judge Giovanni Vergineo

12

Poem by Gabriele Greco L’Attesa*

14

Fiction by Peter Frederick Matthews Writing is Not Like Living

16, 25, 55

Photography by Michaela Paone

18

Essay by Daniel Barbiero

Giorgio de Chirico’s Roman Villa: The Gods never went away

23, 39

Photography by Simone Mantia 24

Poem by Stephen Kieninger

Two Cold Bare Feet

26

Prose by Luca Misuri

Studio 124 Project*

4

5 32 Fiction by Moriah Erickson Ed and Me 42 Art by Simone di Maggio Explain Water to the Fish 43 Poem by Gerry Stewart Stinging the Frog 44 Memoir by Matthew Aquilone Basilica 53, 63 Art by Luca Serasini 54 Memoir by Jason Weiss Transient Light 56 Fiction by Jeffrey Hantover The Beginning 62 Fiction by Michael Edwards Francesca A.D. 1554 64 Prose by LinCan Zhu Amore 66 Poetry & Prose by LinCan Zhu L’Asimo va nella valle delle fate 72 Essay by Scott & Trang Crider Strawbabies 73 Poetry by Martin H. Samuel When in Rome 74 Essay by Lori Hetherington Translation: The challenges, frustrations and what I love 78 Author Bios 83 Submission Guidelines *Parallel Text

Letter from the editor

Lauren T. Mouat

The heat came suddenly to Italy this year. After a spring of rainstorms, grumbling thunder, lightning flashes and lashing hail, at last the tempertures spiked and the air lies heavy over the Duomo in Florence. The sky’s bruised grays and purples alternating with vacant beige now are piercing blue infinities promising heat. Far below, the crowds surge like waves between the Uffizi Gallery and the Accademia. People eddy around the steps of churches, pooling in restaurants and in lines outside gelaterie and wine windows, hoping to capture the perfect taste: a taste of Italy.

The Florentines, on the other hand, are dreaming of relief from the heat and the crowds. “It’s not time to work,” I overheard a shopkeeper gripe today in Italian, “it’s time to go to the sea,” before she deftly switched between three languages as she addressed different customers. It certainly feels like representatives of the entire world have descended on Florence and those silent summer days of a few years ago are behind us.

Poised as we all are for summer vacation - both the real and the longed for - I’m pleased to announce the fourth edition of the Open Doors Review. Memoir meets metaphysics, longing and love meet taste and touch, and the subject of time - in history and memory -pervades. Shifting perspectives allow dual interpretations just as multiple languages cause the reader to pause, perhaps puzzling over a few new words or comparing the difference of encountering a piece you immediately understand, and one that requires more work to comprehend.

6

The pieces in the latest collection of Open Doors come from writers across the globe, united by each author’s connection to Italy. Sometimes that connection comes through family, through travel, through yearning, through making homes in more than one place, in more than one language. As diverse as each author’s ties to the country are the lines of connection between these stories and poems. One of the pleasures of reading a series of pieces like we have curated here is to see the patterns that emerge, across language and medium in fiction, poetry, art, memoir and essay.

Sometimes a comparison is relatively easy to make when a photograph faces a poem or an essay, visually embodying a line or a feeling. Sometimes the connections form in reading one piece after another and seeing themes emerge, re-emerge, entwine.

This, for me, is the value of gathering writing and art of this moment in time and placing one next to the other so that each does not speak just for itself but one to another. In a world where we all have our own channels and our own mountain top from which to shout our stories, let’s not forget the power of gathering, grouping and meeting to see where new conversations can take us.

In order to foster as much opportunity as possible to read and exchange ideas, we are changing up how we offer Open Doors and are making our digital issues completely free! Donations are welcome to cover some of the expense of running the magazine (links at www.opendoorsreview.com) and of couse the main way to help Open Doors thrive is to share it, talk about it, and send in your work.

This issue we welcome two new readers into the team. Monica Sharp and Nora Studholme - a sincere thank you for your work thus far. Thank you to our guest judge and Rome based author Giovanni Vergineo. And as always, a thank you to all our submitters and to our readers.

I hope you enjoy the read, perhaps by the sea. I hear it’s the time to go.

7 -LTM

Interview with Author and Guest Judge

Giovanni Vergineo

Giovanni Vergineo è archeologo, guida turistica di Roma e imprenditore. E’ nato a Benevento nel 1984 ma vive nella capitale dal 2009. Nel 2010 è stato finalista del premio “Italo Calvino” con la raccolta di racconti “Pippe”. Nel 2015 è stato semifinalista del premio “La Giara” con il romanzo “La scomparsa delle Cotolette” selezione regione Campania. Ha pubblicato alcuni dei suoi racconti in varie riviste e raccolte, tra le quali “OschiLoschi” – Nevermind edizioni, Benevento, curata da F. Ignelzi.

Giovanni Vergineo is an archaeologist, tour guide in Rome and entrepreneur. He was born in Benevento in 1984 but has lived in the capital since 2009. In 2010 he was a finalist for the “Italo Calvino” award with the collection of short stories “Pippe”. In 2015 he was semi-finalist of the “La Giara” award with the novel “La scomparsa delle Cotolette” in the Campania region selection. He has published some of his stories in various magazines and collections, including “OschiLoschi” –Nevermind editions, Benevento, edited by F. Ignelzi.

8

Lauren: Raccontaci un po’ del tuo ultimo libro, di cosa parla e cosa ti ha ispirato a raccontare questa storia?

Giovanni: Il mio romanzo “L’antico vaso andava salvato” parla della vita di Gennaro, uno studente di archeologia. È largamente autobiografico, ma ci sono comunque molte parti totalmente inventate. Il libro vuole offrire uno spaccato della vita degli studenti di archeologia, raccontando cosa significa studiare archeologia in Italia al di là della retorica alla Indiana Jones, quali sono le sfide da affrontare quotidianamente, le scoperte, le incertezze sul futuro e sulla carriera.

È anche un romanzo che parla di amore e di educazione sentimentale: la crescita professionale di Gennaro è contemporanea a una ancora più eclatante crescita personale. Durante uno scavo archeologico, Gennaro incontra Lara, studentessa americana di cui si innamora perdutamente. Lara si trasferisce in Italia, e i due intrecciano una drammatica storia fatta di sentimenti estremi: amore, odio, gelosia, rancore.

La personalità del protagonista viene plasmata pagina dopo pagina dai suoi studi e dalle sue esperienze “sul campo”, così come dal confronto continuo con Lara e la sua cultura.

In ultima analisi, il libro vuole essere una riflessione sull’archeologia come scelta di vita, sul soffocante mondo accademico, e sulla fine dei sogni di gioventù , siano essi professionali o sentimentali.

L’ispirazione è venuta dalla mia vita reale, ma anche dal desiderio di fare i conti con alcune delle mie ossessioni più forti: l’archeologia, l’amore, il confronto con culture diverse.

9

Lauren: Quanti libri hai scritto (compreso quelli non pubblicati)? Com’è cambiato il tuo processo creativo dal primo all’ultimo?

Giovanni: Ho scritto due romanzi e vari racconti. Il processo creativo non è cambiato molto: parto sempre da un’idea fissa, un’ossessione, una storia che cova dentro di me e di cui vorrei liberarmi. Poi studio, scrivo di getto, e riscrivo molte volte finché non sono soddisfatto del risultato. Nel mio primo romanzo, “la scomparsa delle cotolette”, ho affrontato il tema della famiglia, dei misteri di famiglia e dell’incomunicabilità tra le generazioni

Lauren: Hai una struttura organizzata fin dall’inizio o inizi a scrivere e poi vedi come l’idea si evolve?

Giovanni: Ho una struttura - base, ma mi piace molto vedere la storia dipanarsi in modo naturale, e scoprirla man mano che la scrivo più che crearla. Dico spesso che la scrittura non è nella testa, ma nelle dita: passa direttamente dal mio inconscio al computer.

Lauren: Quanto della tua esperienza di vita entra nel tuo lavoro?

Giovanni: Moltissimo. Quasi tutti i miei racconti e molto dei miei romanzi hanno una componente autobiografica. Mi piacerebbe però provare a raccontare dei personaggi molto diversi e lontani da me, prendermi una vacanza da me stesso, insomma.

Lauren: Per me ci sono due tipi di autori che apprezzo. Quello che mi da ispirazione di scrivere e creare - leggo e subito dopo devo scrivere. E quello che adoro e mi piace leggere ma non mi da ispirazione allo stesso modo. Qual’è un esempio del primo e del secondo per te?

Giovanni: Di solito, leggere non mi ispira a scrivere. Dagli scrittori imparo le tecniche, lo stile, ne apprezzo la bravura o la genialità, ma la voglia di scrivere nasce da dentro di me. Nasce dal voler tirare fuori ciò che ho dentro.

Mi piace molto la frase di Kafka:

10

Questo mondo tremendo che ho dentro di me. Come liberare me stesso e questo mondo senza ridurmi in pezzi? E meglio essere ridotto in pezzi che venir seppellito con questo mondo dentro di me.

È un aforisma che spiega perfettamente cosa rappresenta la scrittura per me.

Lauren: Scrivi mai in inglese? Se si, com’è scrivere in una lingua diversa dalla tua? Se no, perché no?

Giovanni: Nel mio ultimo romanzo “l’antico vaso andava salvato” ci sono molte parti in inglese. Lara, la co-protagonista, è americana e usa molte parole inglesi. Anche Gennaro, nei dialoghi con Lara, usa spesso espressioni americane.

Nonostante ciò non ho mai scritto in inglese in modo estensivo, quindi non saprei rispondere a questa domanda di preciso. Credo che scrivere in un altra lingua sia un’esperienza fantastica, straniante e complessa. Ma forse è per questo che non lo faccio. Devo pensarci troppo: per quanto parli inglese abbastanza bene, la scrittura in lingua diventa troppo “meditata”, troppo mediata dalla mia parte razionale.

Credo che la scrittura debba uscire veloce dalle dita, e che più veloce esca, meglio sia il risultato. La materia narrativa grezza - su cui poi si intervene con cura e attenzione - deve essere gettata sulla carta in modo istantaneo, violento, veloce. È un’eiaculazione. Non riesco ad eiaculare in inglese.

Lauren: Quale autore italiano consiglieresti di leggere ad un parlante inglese?

Giovanni: Mi verrebbe da dire Calvino, ma è un po’ troppo facile…sicuramente mi sento di consigliare “La Pelle” di Curzio Malaparte. Per quelli più bravi, Tommaso Landolfi e Raffaele la Capria. “Ferito a morte” è uno dei più importanti romanzi italiani ed è praticamente sconosciuto all’estero, il che è un peccato.

11

v

“This tremendous world I have inside of me. How to free myself, and this world, without tearing myself to pieces. And rather tear myself to a thousand pieces than be buried with this world within me. “ - Kafka

L’attesa

Gabriele Greco

E mi chiedi se da qui dalle soglie consunte del mondo si scorgano estese

pianure di neve forse ghiacciai smussati

o altre primavere.

Non è un sogno.

Scalfite le piaghe nei piedi

continueremo a camminare.

Oltre quel punto lontano

c’è un altrove da inanellare.

Non sono una sentinella: non so chie arrivi né chi parta.

Guardo più lontano.

S’abbuia l’orizzonte

e si sgretola il segreto.

12

And you ask me

If from here

At the deteriorated threshold of the world you can glimpse vast plains of snow dull glaciers, perhaps or other springs.

It’s not a dream.

Though we open the wounds in our feet

We continue to walk.

Beyond that far horizon

We encircle the beyond.

I’m not a sentry

I know not who comes nor who leaves.

I look beyond.

The horizon darkens and the secret crumbles.

13

Writing is not like Living

Peter Frederick Matthews

Left and right

He stares at his own face in the mirror and thinks he can intuit from the marginally thicker flesh of his left eyelid, from the way his right eye flashes, two distinct personalities within him.

His left side is slow and heavy. It cannot keep up in conversation. It is happiest sleeping in under several blankets. It likes animals, has a large appetite; when a neighbour died and their furniture was set out in the street, it was his left side who carried up to the flat those two blameless worn-out chairs.

His right side is cooler, and more capable. It is thanks to his right side that he is able to get anything done. When he carries his bag, he notices that he bears it most often over his right shoulder. His right side resents that his left, though physically stronger, shirks its duty.

If there were to be a battle between the two sides of him, the right side would easily outwit and destroy the left. But that is because the idea of the division is in the first place an invention of his right side. His left makes no such distinction, preferring to imagine a unity, even at the price of its own elimination.

14

Fiction

Those ahead of me

In the 10th century, Ahmad ibn-Fadlan set out from Baghdad on a diplomatic mission to visit the Bulghar people by the Volga river. It was there that he met the Rus, the people Russia is named for. He described them as beautiful, as tall as date trees, and recorded how they buried a fallen king in his boat and his many living wives along with him.

One nomadic tribe he encountered were expert horsemen. If a goose passed over, they were able to bring their horse to a regular gallop beneath the flight of the bird and to down it with bow and arrow.

He describes their funeral rites, too.

When a man dies, writes Ibn-Fadlan, they build a house for him and place him in it. Then they bring his horses. He might have one or two hundred. They kill the horses and eat their flesh, but hang the head, hooves, hide and tail around the house-tomb, and they say: These are the horses he will ride to paradise. If he was a great warrior, they build wooden statues of the men he killed and say: These men will serve him in paradise.

Since horses are very valuable to them, they occasionally stall over the sacrifice. Perhaps we don’t need to send all his animals, they think. That is when dreams come to them. They see their comrade in the afterlife, who tells them: Look, my companions have all ridden ahead and the soles of my feet are split from my efforts to follow them, but I cannot catch up.

After that, they kill the remaining horses and hang up their body parts, too. The man returns to them in their dreams and says: Tell my family and my companions that I have caught up with those ahead of me and I have recovered from my great weariness.

Those few of his father’s friends who attended were respectful, but distant, as if they hoped to endure the ceremony and get away.

The priest had offered to say a few words but knowing nothing of the dead man he simply recited some facts concerning the date of his birth (a FIFA World Cup year) and the notable events he had lived through.

There was only one speaker, other than the priest. A friend of his father’s, a man with whom he believed his father had fallen out, before his death, read from Corinthians. The man’s voice was fragile. Emphasis was possible only by going high-pitched, by squeaking.

When I was a child, I spake as a child, understood as a child, thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

His mother wore a yellow hat.

15

16

Michaela Paone

Sea of diamonds

To supplement his income, he finds work reviewing self-published books. The standard format requires a rating from one to five stars, accompanied by a short, explanatory text. His reviews are then, themselves, reviewed. After he sends off the file, a message comes back: This sounds more like two stars, or, Isn’t four a little generous here, given your take?

You may be right, he replies, feel free to amend.

The genre he finds himself selecting most often is memoir. A total stranger writes about their life, their trauma, their success, how they are not always kind to their children or their wives, and it falls to him to write a didactic little report, encouraging them to express these boasts or worries with more concision.

One book he receives is by a man who grew up in Jacksonville, Florida. The man’s entire community - his neighbours, cousins, the friends he grew up with - was done great damage by crack cocaine. The man writes about this, but he shies away from it, too. Each time a painful memory approaches, the author supplies another, better one, for balance.

Writing is not like living, he writes in his report. It may be beneficial to a human being to ignore certain things in order to survive. A life might involve a degree of wilful blindness but, in writing, you cannot turn away your gaze. Your contract with the reader means that we do not care how bad things get – very often we would like them to be worse.

He sends off the review, satisfied with his writer’s insight. But over the next weeks, passages from the book come back to him that he would not have anticipated, like when the author wrote:

It wouldn’t be fair to talk about those years without mentioning how the waves could appear like a sea of diamonds. I spent hours looking out at it, wondering if I could decipher its cryptic message.

And:

Before commercial overfishing, there was always an abundance of seafood. Our family enjoyed these times because the sea was open to everyone, regardless of race.

17

v

giorgio de Chirico’s Roman villa: The Gods Never went away

Essay

Daniel Barbiero

By the time he painted Roman Villa, sometimes known as Strange Travelers, in 1922, Giorgio de Chirico had broken away from his celebrated metaphysical style of 1909-1919. No longer painting deeply shadowed arcades, towers and piazzas, claustrophobia-inducing rooms cluttered with strange objects, maps and mannequins, or trains half hidden behind brick walls, after 1919 he largely turned his attention to an attempt to recapture the techniques of the old masters. Even so, the enigmatic mood that characterized the metaphysical style still could be found in a number of his post-1919 paintings, even if realized less adroitly and with a different iconography. Roman Villa happens to be one of those paintings. It is a strange painting that in its own way is perplexing, but its strangeness is akin to those Renaissance paintings that sometimes can be found in the more obscure corners of art museums—paintings that depict scenes and figures no one has quite deciphered, and consequently get labeled “unknown allegory,” for lack of a better description. De Chirico’s painting would itself appear to be an allegory of some kind.

18

What is immediately striking about Roman Villa is its incongruous juxtaposition of two buildings close up against a vertiginous ridge of bare rock crowned with dark, dense foliage. The rectangular lines of the buildings contrast with the irregular surface of the ridge, which appears to have been inspired by one of Arnold Böcklin’s rugged landscapes— perhaps the cliffs rising from the sea in his painting Prometheus. The resulting spatial tension keeps the buildings on the one hand and the ridge on the other balanced against each other in a kind of mutually atopic relationship: to the extent that each is equally out of place relative to the other, neither one can be felt to be uniquely alien within the overall picture.

reddish-brown female figure seated on a cloud in the upper lefthand corner.

De Chirico painted the ridge in a style reminiscent of 17th century landscape, and for this reason Roman Villa is sometimes referred to as a landscape painting. But it clearly is more than that. The architectural element carries as much of the picture’s visual and narrative weight as does the ridge behind it.

ed except for the corners of their roofs, which contain statues depicting figures from Classical antiquity. On the building to the left, two people sit in chairs on an elevated surface—a very wide ledge projecting from the building on the left— while on the roof of the same building another two people, one pointing into the distance, converse and a third stands alone by one of the statues. A fourth figure, a woman who appears to have been modeled on de Chirico’s mother, looks pensively out of a window in the building to the right. De Chirico’s way of isolating the two conversing pairs and the two individuals helps to create an aura of mystery around them; as in a painting whose allegorical meaning is unknown, we don’t really know what these figures are supposed to be doing or how their situations add up to a coherent narrative--although the painting seems to want us to expect that they do. The two conversations could entail the sharing of secrets, while we can only guess at what the woman is thinking.

The buildings, which may or may not have been inspired by the “Roman Villa” near Fiesole owned at one time by the artist Max Klinger, are rather plain rectangles, for the most part unornament-

But for all the strangeness of the scene as a whole, it is the remaining figure that stands out for its sheer incongruity. It is the almost uncannily intrusive, reddish-brown female figure seated on a cloud in the upper left-hand corner. Her features have a certain muddiness to

19

But for all the strangeness of the scene as a whole, it is the remaining figure that stands out for its sheer incongruity. It is the almost uncannily intrusive,

them and her overall look is imbued with the paradoxical opaque transparency of early Renaissance painting—the result of de Chirico’s use of tempera paint, which he was experimenting with at the time. (And on this question of materials there is another point of contact between this painting and those obscure Renaissance allegories, themselves painted at a time when tempera was in wide use.) The back of her garment billows out like a sail; she’s bent slightly and holds her left hand to her head in a posture suggesting an attitude of grief or melancholy. Who she is supposed to be specifically may ultimately be a matter of speculation, but nevertheless she is the key to an allegorical reading of the painting.

Picatrix, a 10th or 11th century Arabic illustrated work on magic and astrology translated into Spanish and later into Latin; the Aratea, a ninth century astronomical work that included illustrations of the mythological figures associated with the planets and constellations; and the medieval encyclopedic tradition generally. As they passed through these texts their appearances mutated in sometimes bizarre ways, but they never lost their capacity to symbolize natural forces, human virtues and failings, and moral lessons because they were archetypes that, as Seznac puts it, “served as vehicles for ideas so profound and so tenacious that it would have been impossible for them to perish.” And so they didn’t.

The figure on the cloud has all the appearance of a Classical deity overlooking a contemporary scene. She brings to mind Jean Seznac’s classic work of mythography, The Survival of the Pagan Gods. Not for providing a clue as to her specific meaning or function, but for Seznac’s overall idea that the Classical gods had never disappeared from the collective memory and imagination of the West, but through a process of “misunderstandings, confusions, [and] false interpretations” at the hands of grammarians, mythographers, and moralizers, they survived the ascendancy of Christianity in Late Antiquity and continued to exist in one form or another through the Middle Ages and beyond. Seznac shows that their survival depended on the circulation of such texts as Fulgentius’ circa 6th century allegorical Mythologiae; the

They turn up in de Chirico’s paintings in many forms, often indirectly. He frequently depicted their temples, statues, and seers, and in his post-1919 work occasionally depicted them directly. They seem to have been for him what we now would call condensed symbols—symbols that reach beyond their specific meanings to signify the larger, complex sensibility that gave rise to them and in which they were embedded. The specific sensibility these figures symbolize is the Classical Mediterranean sensibility. We know that de Chirico always felt the proximity of the Classical past, in part from having grown up in Volos in Thessaly, where his father worked as a railroad engineer. Volos was once known as Iolkos and was the point of departure for the Argonauts; nearby Mount Pelion was the purported home of the cen-

20

taurs. Both myths seem to have played a role in de Chirico’s early imaginative life. His pre-metaphysical paintings include scenes of centaur combats influenced by Arnold Böcklin’s mythological paintings, and he identified himself and his brother Andrea (who painted and wrote under the name Alberto Savinio) with the Argonautica’s Dioscuri. In addition to myth, de Chirico was inspired by the early Greek thinkers, and particularly by the gnomic fragments of the philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus.

The price of admission to this “museum of strangeness” was a sensitivity to a certain affective coloring on the part of the visitor. The metaphysical world is a world permeated with a feeling, or Stimmung, that de Chirico often described as “fatality” and that could only be sensed in a spirit of solitude and melancholy.

It isn’t surprising, then, that something of the Classical sensibility carried over into the metaphysical aesthetic. In fact one of the keys to the attitude de Chirico named “metaphysical” is a nostalgia for the Classical past and the mentality it was reputed to embody. This particular kind of nostalgia manifested itself in his feeling that the numinous world of the ancient Mediterranean somehow persisted into the present. That despite everything the gods survived, and that one could somehow sense them.

cane meanings, and in relation to which one must adopt a divinatory stance. To the metaphysical attitude the world is a series of enigmatic signs to be read and deciphered, much as the Greeks read and interpreted the world and its furniture through their philosophical speculations, their oracles, dreams, and miscellaneous divinatory practices. De Chirico saw architecture, statuary, even shadows of a certain length and depth as just such enigmatic “symbols of a superior reality,” as he wrote in his statement “On Metaphysical Art.” An earlier statement from the famous Eluard Manuscript asserted that to see the enigma in things, which is to say to see them metaphysically, would be to “live in the world as if in an immense museum of strangeness.”

The metaphysical attitude, which de Chirico described so often in his written statements and reflections, was above all a particular way of being in the world. It is a way of being in which one finds oneself in a world permeated by portents and ar-

The price of admission to this “museum of strangeness” was a sensitivity to a certain affective coloring on the part of the visitor. The metaphysical world is a world permeated with a feeling, or Stimmung, that de Chirico often described as “fatality” and that could only be sensed in a spirit of solitude and melancholy. Here, too, the Classical Greeks set an example for him. As he wrote in the Eluard Manuscript, he liked to imagine Heraclitus lost in lonely contemplation, “meditating in the faint light of dawn,” and he asserted

21

that it would be a “major error” to suppose that the Greeks were “imbued with a spirit of optimism about life.” It is that tragic side of the Classical mentality that particularly dominates the metaphysical Stimmung and leaves its traces in the images de Chirico created. It comes across most obviously in the long shadows, nearly empty courtyards, and overhanging mood of lost time in the paintings of 1909-1919—the “metaphysical period” proper—but isn’t entirely absent afterward. It pervades Roman Villa not only through the overall strangeness and atopy of the scene, but through the specific objects de Chirico chose to depict, particularly the statues. Not only do the statues in the painting make direct allusion to the persistence of the Classical past, but as in the earlier metaphysical paintings, they carry an emotional weight arising from de Chirico’s general insistence on associating the figure of the statue with the tragic sense. In a passage from his statement “Statues, Furniture, and Generals,” which is roughly contemporary with Roman Villa, de Chirico observes that “on top of a palace, against the southern sky, [the statue] has something Homeric about it, a kind of severe and distant joy, mixed with melancholy.” Nothing better sums up what Roman Villa seems to be about, or the feeling it seeks to convey.

sensibility of Classical antiquity. And that is what is so perplexing about her. She is the trace through which the pagan gods, as archetypes and condensed symbols of a world full of fatal portents and omens, signal their refusal to go away.

And it is here that the goddess in the cloud discloses her meaning, along with the meaning of the allegory encoded in Roman Villa. She represents the survival of the metaphysical outlook that persists in de Chirico’s work and with it, a corresponding survival of the divinatory

22

v

23

Simone Mantia

two cold bare feet

Stephen Kieninger

cool wind; Cagliari morning. Winter; up on a Pirri rooftop. cold espresso, a damp cigarette; birds cooing, dogs barking, smoke mimicking mine from a chimney across the street wafts upward toward elephant grey skies. fog obscures the view of Sella del Diavolo.

a patch of sunlight on the city in the distance slowly fades away. burning wood and olive branches, simple, subtle, supple noon.

Michaela Paone

24

25

Studio 124 project

Luca Misuri

Italiano

Uno spazio vero, tangibile non virtuale sembra essere una vera e propria chimera oggigiorno. L’unico atto avanguardista in questa epoca di arte modificata digitalmente dall’intelligenza artificiale e spruzzata nel freddo universo virtuale della rete, è la ricerca dell’atto creativo, generato in quei “laboratori” rinati come bulbi di tulipani nel “compost” fertile depositato nei due anni di Covid. La reazione di menti creative a questo shock imprevisto ha ridato possibilità all’arte di germogliare in tante singole ed uniche forme espressive, dando vita, in molti casi, a spazi co-working.

Con i suoi numerosi artisti, Livorno sembra riassumere quanto appena accennato. Un posto che pullula di creatività fin dalla sua nascita come porto Mediceo agli albori del ‘600. Il porto franco, aperto ad ogni religione e privo di un ghetto (altro elemento di unicità) ha attirato ogni tipo di popolazione e conseguentemente svariate culture all’interno delle sue mura. I risultati di questo incipit alternativo sono personalità forti e contaminate, come quella di Modigliani e Mascagni affermatesi ai piani alti dell’arte di primo ‘900.

Con Spazio 124 sogno di dare visibilità a nuove personalità artistiche, ridestando l’interesse per un fermento creativo che rappresenti il periodo storico in corso di svolgimento. È forse giunta l’ora di svincolarsi dalla rete e tornare a cercare nei luoghi veri, tangibili e non virtuali ?

26

These days it’s becoming a rarity to find a real, tangible, non-virtual space. It’s an age of art that has been digitally modified by artificial intelligence and sprayed into the cold virtual universe of the web. The only avant-garde act seems to be the search for the creative act itself, generated in “laboratories” reborn like tulip bulbs in the fertile “compost” created in the two years of Covid. The reaction of creative minds to this unexpected shock has given art the possibility to germinate in many single and unique forms of expression, giving life, in many cases, to co-working spaces.

With its numerous artists, Livorno seems to embody this concept. A place brimming with creativity since its inception as a Medici port at the dawn of the 1600s. The Free Port of Livorno, open to all religions and without a ghetto (another element of uniqueness) has attracted a diverse population and various cultures within its walls. The results of this alternative culture are decisive and distinctive personalities, such as that of Modigliani and Mascagni who established themselves on the upper levels of early 20th century art.

Today I would like to restore visibility to new Livornese characters, reawakening interest in a possible new artistic movement that represents the ongoing historical period. Perhaps the time has come to disengage from the web and go back to searching for each other and for art in real, tangible and non-virtual places.

27

English

Meet the artists

Italiano

Simone Mantia è un fotografo e ingegnere livornese.

Scopre la fotografia da adolescente, iniziando a fotografare paesaggi e ritratti. Dopo un periodo di pausa, nel 2017 riscopre la fotografia di strada. Da subito è attratto dalla possibilità di congelare momenti ordinari e di raccontare, mediante le immagini, frammenti di vita. Nel 2019 inizia ad interessarsi maggiormente alla fotografia documentaria, realizzando il progetto “Doppie Visioni” sulle gare remiere livornesi.

E’ stato finalista in diversi concorsi nazionali e internazionali, tra i quali il MSPF (Miami Street Photography Festival), il LSPF (London Street Photography Festival) e l’ISPF (Italian Street Photo Festival). Nel 2018 riceve la menzione d’onore all’Urban Photo Awards e, nel 2020 e 2022, è tra i vincitori dell’Observa Street Photo Festival.

Instagram: manti.simo Flickr: Simone.mantia

Michaela Paone

“Un click al giorno toglie il medico di torno”. Che sia reflex o cellulare è così che sento il mio fare “ click”, mi regala una buona disposizione verso la vita, mi permette di creare mondi affini o paralleli, comunque creare per creare. In genere non progetto i miei scatti, tutto avviene in modo del tutto naturale ed improvviso secondo il mood del momento e l’ambiente circostante. Amo creare un’interazione tra la mia figura e ciò che mi circonda divenendo un unicum. Altre volte prediligo alterate la realtà creando un nuovo punto di vista, una visione distorta.

28

Simone Mantia is a photographer and engineer from Livorno.

Mantia discovered photography as a teenager, starting to photograph landscapes and portraits. After a break, in 2017 he rediscovered street photography. He was immediately attracted by the possibility of freezing ordinary moments and of telling fragments of life through images. In 2019 he began to explore documentary photography and he made the project “Doppie Visioni” based on the Livorno rowing competitions.

He has been a finalist in several national and international competitions, including the MSPF (Miami Street Photography Festival), the LSPF (London Street Photography Festival) and the ISPF (Italian Street Photo Festival). In 2018 he received an honorable mention at the Urban Photo Awards and, in 2020 and 2022, he was among the winners of the Observa Street Photo Festival.

Instagram: manti.simo Flickr: Simone.mantia

Michaela Paone

“One click a day keeps the doctor away”. Whether it’s a camera or a mobile phone, this is how I get my “click” in. It gives me a good disposition towards life and allows me to create similar or parallel worlds. Generally I don’t plan my shots, everything happens in a completely natural and improvised way according to the mood of the moment and the surrounding environment. I love to create an interaction between my subject and the surroundings, blending the two into one thing. Other times I prefer to alter reality by creating a new point of view, a distorted vision.

29

English

Italiano

Simone Di Maggio

Simone Di Maggio (DMBT) ha 45 anni e la sua produzione artistica è quasi integralmente musicale, sebbene la sensibilità verso l’arte e le frequentazioni di amici artisti sia per lui una costante da sempre. Da quasi tre anni sperimenta con il disegno a china e gli acquerelli, riprendendo un percorso interrotto a fine ‘90, stavolta con la volontà di trovare il proprio equilibrio tra forma e colore – immerso nella libertà e la meraviglia del gesto pittorico.

Luca Serasini

Sono nato a Pisa nel 1971.

Ho iniziato a dipingere nel 1996 e dal 2003 ho iniziato ad usare diverse altre tecniche, dalla fotografia ai video e alle videoinstallazioni fino a giungere, nel 2013 alla land art, e grazie ai miei studi di elettronica, a creare light box e dispositivi interattivi.

Uno dei due progetti che porto avanti è il Progetto Costellazioni che parte dalla domanda se abbiamo ancora noi, oggigiorno, realmente bisogno delle stelle. Nato inizialmente come progetto di land art si è via via articolato nelle forme più diverse attraverso il video, la fotografia, installazioni interattive, pittura e grafica.

I lavori in mostra appartengono al ciclo Population I, lavori su carta e acrilico in rilievo che sviluppano, in 21 lavori di piccole dimensioni, il tema della popolazione di stelle. In cosmologia le stelle sono divise in popolazioni, che a seconda della loro composizione chimica ne viene compresa l’età. La prima popolazione (Population I appunto) sono le stelle più giovani dell’Universo.

30

v

Simone Di Maggio

Simone Di Maggio (DMBT) is 45 years old and his artistic production is almost entirely musical, although the sensitivity towards art and the acquaintances of artist friends has always been a constant for him. For almost three years he has been experimenting with ink drawing and watercolors, resuming a path interrupted at the end of the 1990s, this time with the desire to find his own balance between form and color - immersed in the freedom and wonder of the pictorial gesture.

Luca Serasini

I was born in Pisa in 1971.

I started painting in 1996 and since 2003 I have started to use various other techniques, from photography to video and video installations up to land art in 2013, and thanks to my studies in electronics, to create light boxes and interactive devices.

One of the two projects I am carrying out is the Costellazioni Project which starts from the question whether we still really need the stars today. Initially born as a land art project, it gradually developed into the most diverse forms through video, photography, interactive installations, painting and graphics.

The works on display belong to the Population I cycle, works on paper and acrylic in relief that develop, in 21 small-sized works, the theme of the population of stars. In cosmology, stars are divided into populations, which, depending on their chemical composition, include their age. The first population (Population I) are the youngest stars in the Universe.

31

v English

ed and me

Fiction

Moriah Erickson

The Gun I.

Ed Prignano was my father’s best friend. A short, rotund Italian man with thinning hair and soft brown eyes, Ed was always around when I was a kid, standing at the bottom of the porch stairs bullshitting with my dad while they both sipped Pepsis out of curvy, returnable glass bottles. I never paid much attention to what Ed and my dad were talking about, but I was fascinated because Ed Prignano wore a gun in a shoulder holster everywhere he went. Summertime was the best, he would wear those stereotypical Italian-guy A-shirts, white ribbed tanks stretched tight across his abdomen, gold chain glinting in the sunset, and black sunglasses. The holster was leather and formed to his body, the gun a snub-nosed .38 revolver. He wasn’t worried that anyone would see it, and he certainly didn’t try to hide it. He would rest a hand on it as he stood down on the sidewalk along 24th Avenue, laughing so raucously that Carlotta Caliendo, the old lady next door slammed her window shut, glaring at both of them.

My neighborhood was full of Italian folks; my father knew them all. They’d wave hello as they walked past on their ways home from Naples Fruit Market, and my father would raise a hand in response. He liked everyone fine, but he loved Ed Prignano. We’d sit on the porch steps, my dad and I, eating a plate of dry salami and pecorino Romano that my father would cut with his pocketknife against his thumb. He’d always offer Ed some, and he’d always take a slice of each, folding the salami around the cheese into the shape of a taco, stuffing it into his cheek and chewing slowly, savoring the salty, oily meat. Nobody else from the block stopped as long as Ed did, and nobody shared our feast.

The sun would slip behind the houses as my father and Ed talked, first reflecting off the windows across the street like fire, then welcoming in the strange flat light of dusk in the neighborhood. The halogen lights surrounding the car lot at Al Piemonte Ford and the neon around the

32

top of the Harlow Grill would snap on in succession buzzing to life. Ed Prignano would slap his hairy arm against the bite of a mosquito, and my father would tell me to head in. Sometimes I would stall, wandering out into the yard to pick up my jump rope or my skateboard, but he would always wait for the serious conversations with Ed until I was inside, and the big door was shut. Even in the summertime, I was expected to shut the door to the front porch behind the screen, so my father could speak with Ed in privacy. Sometimes the neighborhood cop, Skipper Fanara would stop along the road and roll down the window and talk to Ed and my dad, but they were never in trouble, at least not the kind the cops were interested in in Melrose Park.

I didn’t know what they talked about, but I wondered. I would open my bedroom window as far as it would go and catch bits of their conversation here and there, but never enough to fully understand. All three of them would laugh occasionally, but it was more murmured seriousness than jovial friendship. I’d overhear words like “bag” and “asshole” and “Saturday” and wonder what any of that could possibly mean, as I drifted off to sleep, my childhood bed facing south and the breeze from the city wafting through the stuffy room in our bungalow.

Ed Prignano owned the funeral home on North Avenue, a building that was low brick and resembled an animal hospital. It didn’t have any windows, except in the door. He did all the neighborhood funerals, including my grandmother’s when I was twelve. It was strange to be in a build-

ing like that in our neighborhood, even then, as my dead grandmother lay in a casket on display, because Ed was there, and he was the funeral director. I recall my father shaking his hand, slapping him on the shoulder as they stood outside the viewing room that stunk of lilies and my father’s dead mother. I wanted to ask if Ed had his shoulder holster on, if the .38 was loaded in case of unruly funeral-goers, but I knew better than to be what my father deemed a “smartass.” At twelve, it seemed to be a fair question, but I kept quiet in order to maintain the somber atmosphere. I instead sat in one of the brown stacking chairs with cracked vinyl sticking to my bare legs quietly next to my brother, wishing the air conditioner was a little cooler.

By that time, when I was twelve, I knew Ed Prignano was a low-level crook, and by association, my father probably was, too. I wondered if Skipper Fanara was too, but logic told me that cops were “good guys” and the idea of a dirty cop, even a slightly dirty one, wasn’t even anything I could entertain.

I had been rummaging through the back seat of the old Chevy that was in our garage and found a bank bag with some cash in it stuffed under the seat. Too scared to lift even a $20, I stuffed the money back into the bag and shoved it back under the front seat, my hands sweating and shaking, as if mere contact with dirty money somehow made me a crook. I crawled out of that backseat and slammed the door on that dusty Chevy and ran into the house, not realizing my walkman was still laying on the back-

33

seat, Madonna blaring through the foam headphones until I got inside. I tried to reason to myself that the money was just a deposit from the garage that my dad worked at that he had forgotten in the Chevy the last time he drove it, but there was an underlying voice that told me that was a dumb, childish idea.

My father got home shortly thereafter, and his route of entry was through the garage, where he undoubtedly heard “Papa Don’t Preach” coming from the back of the old car. He came into the kitchen looking inflamed, his face sweaty and beefy. “Were you in the car?” he asked me, as I laid out the plates for supper.

“No,” I lied, blush rising from my neck up into my cheeks. I wouldn’t look at him, because if he saw my eyes, he would know I was lying. I’m fairly certain he knew anyway.

“Someone left your music on in the backseat,” he said, handing me the walkman and the balled-up wires to the flimsy headphones. “I hope whoever it was wasn’t snooping around in something that wasn’t their business.” I have never been happier that I didn’t take any of that money! And boy was I glad that my father was as uninterested in talking about what else was in the backseat of the car as I was. I ate my dinner as fast as I could without choking, my father’s eyes honed on me the entire time. I don’t think anyone was more relieved than when I shoveled the last bite of my mother’s brarciole into my gullet and asked in the same breath “Can I be excused?”

The next day, Ed Prignano and my fa-

ther were in the garage, talking about the keys for the Chevrolet, and how they were going to have to keep it locked from then on. I never asked why, and I only offered them each a bottle of cold pop. The best I could do to make my 12-year-old-self seem innocent. They each screwed the top off the bottle with their tough, dirty palms, and tossed the tops on the garage floor with a clang before taking swigs of Pepsi.

Ed Prignano raised his eyebrows at me that day, so far above the frames of his black sunglasses that I knew it couldn’t not be intentional. I knew he knew what had happened, but neither of us said a word about it, nor did my father. I just handed them their sweaty, cold bottles and went back into the house. From then on, I avoided Ed Prignano like the plague, and I can’t imagine that my father didn’t notice.

The Death II.

Terror. The only emotion I felt was terror. In the sweaty, salmon-colored high school bathroom, terror washed over me in waves of frigid air, as though the air conditioner was blowing directly on me, which it wasn’t since it was January. I glanced up from the sink, the white porcelain steadying my wavering stance and stared at my reflection in the dirty bathroom mirror. Long hair, brown, tied back from my face with an ugly barrette. Short forehead. Blue eyes that were never as striking as I thought they were. Olive skin gone drab. Dark circles under my eyes. A nose that would always be a little

34

too big for my face. Thin lips, dry, parted. The pallor that hung over my face made me look sick, and in that moment, I felt it. My stomach twisted into my spine, creating a dropping feeling like when a roller coaster sank. My gaze swayed from the mirror back to the sink, where my hands still gripped the sides for stability. I was damp with sweat, the hair along my face stuck to my skin slickly, and my neck was wet under my hair.

The door burst open, and Janelle Esposito and Cari Woods walked in, talking about something mindless. They glanced at me only briefly and let themselves into the stalls, slamming the doors behind them. I remembered in that moment to breathe and inhaled the heavy air with a shudder. “Hey, are you ok?” one of them asked me, when clearly, I was anything but.

“Yep, great,” I responded, picking my backpack up off the tile floor. I heaved it onto my shoulder and charged out the door, the world spinning, before any more questions could be asked. The hallway was vacant, and I was relieved to not have to meet the masses of talking and laughing students who were my peers at that moment. The windows into the classrooms revealed desks in rows, each with a student in it. Third period. I should be in Civics with Mr. Beem, listening to him prattle on about local elections, his sandy beard moving in time to his words, and here I am in the hallway, desperately searching for a way out. And I should know, I’ve gone to this school all my life, but everything looks a little foreign, and I’m unsure of everything. Except one

thing: nothing would ever, ever be the same.

There would be no junior prom, no senior prom, no Columbia College in Chicago, no summer job, no staying up all night with my friends, riding around town in the backs of their cars. A giant, tectonic shift had happened, and I was falling into the vast abyss it had created without a parachute or safety net of any sort.

The night before, as I slept in my upstairs bedroom in the bungalow on 24th Avenue West, the furnace-dry air surrounding me like a shroud, oblivious to everything, my mother died.

Sure, she had been sick. But she had been sick for as long as I remembered. Huntington’s disease made her first tremor, and then shake, and then flail uncontrollably. As a child, I remembered the pages of the books she would read me flapping back and forth as though caught between the spokes of my bicycle. She would ask me to button her shirts when her hands would quake, and she could not force the button into the hole. And I understood that she was sick, and that Huntington’s was progressive, and that things were getting worse, but that was all on another level.

Now she was dead. And that meant a lot of different things for me, my family, and everyone who had anything to do with us.

When I had gotten up, my father was at the kitchen table in his undershirt, drinking coffee. Ed Prignano was there, too, and he looked solemn. Ed never looked

35

solemn unless there was a good reason. He was my father’s best friend, which was kind of funny. What mechanic is best friends with the local funeral director, after all? Neither of them could look at me, but I knew something was wrong when I walked into the kitchen. Ed held out a cup of coffee to me, which my father would never allow me to drink. He didn’t scold me or Ed when I accepted it and took a long drink, even though it was too hot and burned my tongue. Ed opened his arms to me, which was also very unlike him. Ed was a jolly guy, but not a hugger. He was more of a handshake guy, or if you were a pretty woman (which I was not) you would get a kiss on the cheek and maybe a pinch on the ass. Nobody said anything, and nobody looked up. I let Ed hug me, his big arms smashing me against his robust belly. I could feel the butt of the .38 revolver he had worn in a shoulder holster since I was a kid pressed against me. Ed smelled like lilies and cigar smoke, which I thought were funny things for a man to smell like. I was used to my father, who smelled like motor oil and cinnamon gum and sometimes Hall’s cough drops. Ed let me go finally, and I was able to take a breath. My father raised his eyes to look just past me, and I could see they were red and watery. He did not say a word, just made this pathetic wheezing sound, and I knew.

I pulled my backpack off my chair and hoisted it onto my shoulder. I turned away from Ed and my father, neither who had said a word, and walked through the dining room and the living room to the front door. In the dining room, my

mother’s hospital bed was empty. She had lain there for the last three years, when she could no longer walk. Her arms had worked overtime, even when she was asleep, firing back and forth in terrible thrashing movements, her head ticking to one side. The constant movement in that room had stopped, and with it, everything else.

I opened the door and stepped out into the frigid dawn. Melrose Park is not a welcoming city, especially in January. The newspaper was on the porch, wrapped in its blue plastic sheath. I could see my breath, and I didn’t have a coat on. I didn’t know if my brother had left for school or if he was up or if he knew anything, but I also didn’t care. The storm door slapped the frame behind me, making a metallic crash like something breaking.

“You don’t have to go to school today if you don’t want to,” Ed was standing in the doorway behind me, the storm door between us. “Nobody is going to make you go.”

“I’ll go,” I told him, wanting him to be someone else. Anyone else. I hated that Ed Prignano loved my father so much that they had probably been planning for this moment for years. I wanted him to not be so comfortable in our house that he could sit at the kitchen table in his velour pants and t-shirt. I wanted Ed Prignano never to have touched my mother’s dead body, but I knew that he had, and he would again. And then we would have to look at her, knowing that he had touched her.

“It’s over now,” he said. He meant all my

36

mother’s suffering, and the not knowing, and the tiptoeing around the fact that she was going to die soon, and I knew what he meant. But a lot of other things were over, too. Him saying that was supposed to bring me some relief, I think, but all it did was make me more furious.

I was sure it was over. And at the same time, it was the beginning of something wholly different and horrifying. “I’m ok, Ed. Mr. Prignano. Just take care of my dad.” I turned away from the house I had spent my entire childhood in with my sick mother and walked down the porch steps to the sidewalk. Everything was spinning, whirling around me in slow motion like a snow squall.

Ed said something else, but I don’t know what it was. He stepped back and closed the big door between the indoors and the storm. I walked down the sidewalk and somehow ended up at Proviso West High School, frozen half to death, and in a tunnel of numbness that somehow was not grief for my mother, but horror at what my life would turn into.

The Mess III.

I wrapped my hands under my belly, which was just starting to pooch out a little bit. What better way to mourn a mother than to become one, right? My tee shirt wasn’t even getting tight yet, and school was finally over. Graduation had washed over me, the flowing orange gown tickling my calves as I waited in the June heat for my name to be called so I could cross the stage, shake the vice principal’s hand, and take my diploma. I had passed all my

classes in the fog of sadness and fury but had no plans for the future.

I had dreamed of college once. I had even taken the train into the city and toured Columbia College down on the lakefront, marveling at its proximity to the Art Institute and the cool young people wandering around with their paint splattered clothes and the canvases they lugged back and forth between their studio and wherever they stayed. I wanted to write. Columbia had a creative writing program, and it was close enough to home so I could take the el into the city for classes. It all seemed well thought out, and almost planned, until my mother died. And then I got pregnant. And then it was not even a topic of conversation anymore. I was just going to have to go to work.

Of course, I could still write. My father made that clear with his graduation gift to me: a Macintosh laptop loaded with a word processing program. He made a production of giving it to me, too. The slick white box was wrapped in orange iridescent wrapping paper. I tore it off and my father beamed. “For your stories,” he said.

He didn’t acknowledge that the application to Columbia College never got sent, it just sat on the sideboard in the dining room until I threw it out one day in a cleaning spree. He didn’t acknowledge my growing midsection. He didn’t acknowledge that my mother was gone. He was off in the cloud of his own sadness, floating through the days and weeks and months. Ed Prignano was an ever-present feature in our lives. He brought coffee

37

in the mornings for my father, and sometimes lasagna from his wife’s kitchen in the evenings. It was a good thing, too, because without him, we would have all perished on a diet of boiled hot dogs and frozen pizzas.

Graduation brought an onslaught of gifts, mostly in the form of cash, some generated from pure pity. Since I was not going to college, I spent it on a rental for the summer up in Sturgeon Bay. Wisconsin was where I went to forget, and all I wanted to do was forget. My boyfriend was coming along, his presence looming and omnipresent. But he had a car. And he said that he loved me. What did I know at 17 about love? So we planned our trip, and once graduation was over, we left.

My father and Ed stood in the driveway together and watched us go. The air was heavy and the air conditioning in the car was broken. I sweated; my hair stuck to my forehead. Andy, my boyfriend, sweated, but in a red, angry kind of way. I brought the laptop along, hopeful that I could write something worthwhile. Ed and my father both looked a bit bewildered, but they smiled and waved as we backed out of the driveway.

Andy laughed at the idea when I told him. “You think you are going to be a novelist?” he asked in his incredulous way.

I didn’t answer, just looked out the window as Illinois and the city retreated behind us in a sweltering haze. I wondered what my father would do when I was gone. I had hugged him before I left, feeling his frame fold inward like a husk. Ed

had been sturdier when I hugged him, and he had whispered to me to “call if I needed anything.” It was like Ed Prignano was a mind- reader. I had no idea I would need him, or anyone, but I would.

The cabin was small and dark, looking out onto Lake Michigan. There were two rooms with a kitchenette. The bed was too soft, and the chairs were mismatched, but when the windows were open, the lake

38

39

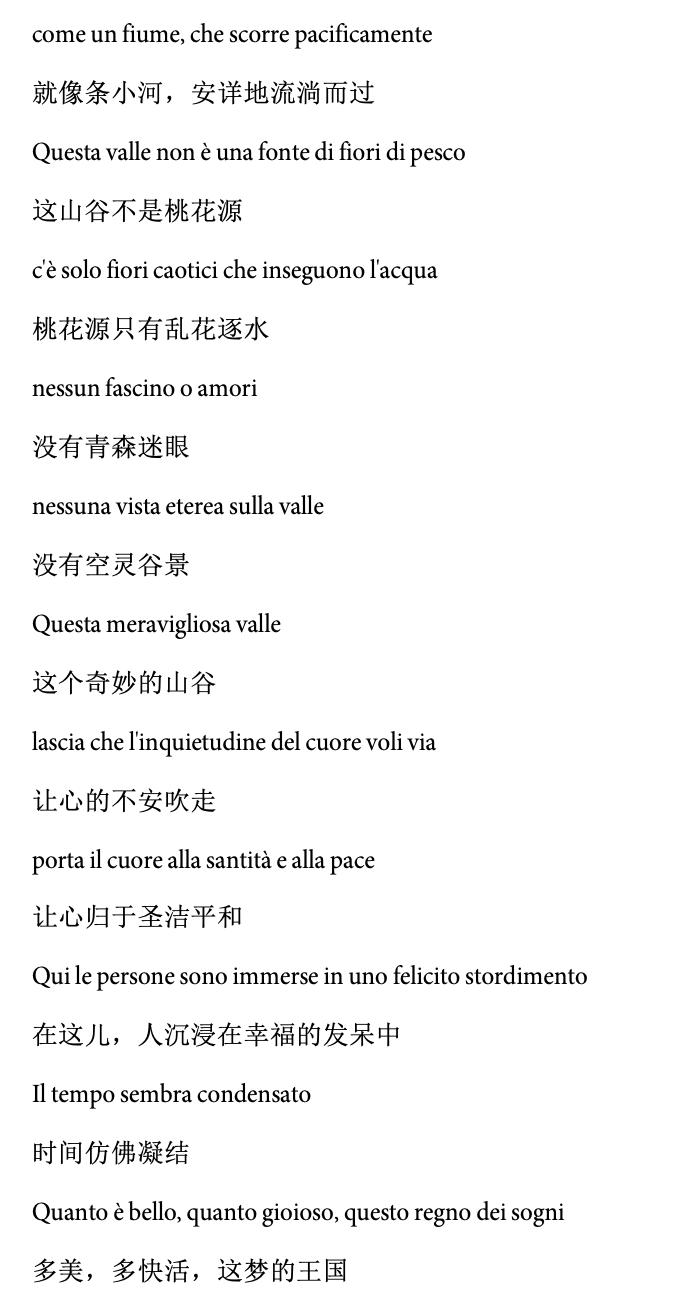

Simone Mantia

breeze blew through the little cabin and kept it cool. I set the laptop up on the table, plugged in and open to the word processor. Andy laughed again. I wrapped my hands around my belly, protective.

I knew how to be a mother before I knew how to be anything else, it turns out. I wanted to be a writer, but I couldn’t make the words come. Andy just scoffed at me. I finally told him “I’m glad I didn’t try to get into Columbia College. It would have been a huge waste of money.” and he agreed. I could feel my child turning inside me, a strange fluttering inside the tightness of my abdomen.

“You should just get a job when we get back to Melrose. The Harlow Grill always wants someone.” His voice hurt my ears, and his sentiment hurt my heart. I nodded and closed my eyes. I could see my mother’s face there, before her cheeks were bony and her eyes sunken. It was like looking at a favorite picture: her in her purple and grey parka at a Halloween party, her hair curled away from her face Farrah-Fawcett style, a drink in her hand, and her lip curled up in an expression that I recognized myself making. Tears welled under my lids but refused to spill onto my cheeks, stinging. “Hey, c’mon. Stop it.” Andy said. “I know you can hear me. Don’t be sad.”

I opened my eyes and stared at Andy through my tears. “I don’t think I can do this, Andy.” He was a blur, his maroon t-shirt melting into the knotty pine woodwork, his face an ugly smear.

“What? The summer? Me? The baby? What are you talking about? Should I just

leave now? What the fuck?” His voice went up an octave when he was agitated, and he was getting there.

I felt terrible. I was just so sad, so deeply and tragically wounded, that I could not imagine spending the whole summer listening to Andy tell me what I should do and try to be receptive to it. I couldn’t hear myself think when he was around, always trying to pull me out of my sadness. “You should just go back to Melrose Park. I just need to be alone.”

“What, so you can write your book? Or do you have some boyfriend here?” Andy was screeching. I put my head down on the table. I slapped the laptop closed.

“Just go, Andy.” I sighed. He had wanted to since I had told him I was pregnant, and this was his chance, maybe his only one. I willed him to take it, but instead he took hold of my hair and yanked my head up off the table. My eyes flew open, the back of my head seared as he twisted his hand into my hair.

“I drove your dumb ass all the way up here and that’s it now? Just go?” He was in front of me, I could feel his breath on my face with each word. I wrenched myself around, trying to get out of his grip.

“Fuck this, Andy. You want to leave, leave.” I twisted again, feeling my scalp scream in protest. “Now let go.”

He did, and my head throbbed in response. I glared at him, and he glared back. How this had turned ugly so fast and for no real reason was beyond me. But I wasn’t about to backpedal on any of it. “Leave. Go back to Melrose. Go any-

40

where. Just get out of here.”

His lip curled in disgust. He turned on his heel and walked into the bedroom, and flopped on the bed, the springs shrieking. “I’m not going anywhere.”

I walked out the door into the evening air, the coolness a shock from the stuffy cabin. I did what I knew I would all along. I called Ed Prignano.

Ed’s voice was rough on the phone, but he agreed. I sat outside on the porch, a yellow halogen bulb buzzing above me. I could feel the baby churning around inside my belly as I waited. I could feel my future changing. Andy was snoring, I could hear him through the screen door behind me. And I realized I hated the sound of him, and the idea of him. Mosquitoes buzzed hungrily in my ears, and I slapped at the sides of my head.

Ed arrived in his black Lincoln Town Car, crunching up the gravel driveway. When he got out of the car, he was sweating. I got up and walked toward him. I had never been happier to see anyone, especially Ed Prignano. I wrapped my arms around him like I would my own father and sobbed into his shoulder. The leather from the holster pressed into my cheek. Ed held me like that for a while, probably longer than he was comfortable with. But he was an expert on grief, and well-versed in letting people let it out. And when no more tears would come, he asked, “Where is he?”

I pointed at the door, not knowing what was going to happen to Ed or Andy or me or my baby or really anyone. Ed walked to the door, opened it, and walked in-

side. I got into the Town Car, in the back seat, and curled up like a grieving widow on her way to her husband’s funeral. I imagined how many people had wept in the back of Ed Prignano’s Lincoln, and thought their tears had somehow made the leather of the seat softer.

I didn’t see Andy come out of the cabin. I didn’t see Ed behind him, the snubnosed .38 pressed into his back. I didn’t hear Andy get into his car or shut his door or drive away. I barely heard Ed get into the driver’s seat, but when the Lincoln started up, I sat up.

“Thank you, Ed. Mr. Prignano. Ed. I’m not sure what to call you,” I said nervously.

“Ed’s good.” he said, tucking the pistol back into the holster. “You ok, kid?”

“Yeah, I’m fine. I just got scared. I think I’m gonna go back inside now,” I replied.

“You have writing to do, kid.” Ed tapped a cigarette out of his pack, lit it, and blew a plume of smoke out into the night. “When you decide to come back to Melrose, give me a call. I’ll come get you. And you’ll have a job at the funeral home when you get back. Your dad told me you are in a bind.”

“Thank you, Ed.” was all I could muster.

Ed coughed and took another drag on his smoke, the ember lighting up his face. He was gleaming with sweat even though the night was cool. And his gun was at his side. Just like always.

41

v

stinging the frog

Gerry Stewart

The sting in the tail is that you knew.

They didn’t hide their poison. Scorpions hold it aloft so you can’t deny its risk if you tread too close or break the calm.

When all the pain and numbness wears off remember you are the one that can swim.

You trusted, but drowning is also in your nature, pulling the waters over you until they are all you can breathe.

Seal your lungs tight, drifting alone is easy if you give in to the current’s pull.

43

Simone Di Maggio

Basilica

Life was really lived in the kitchen and in the big grassy yard where my grandfather also raised vegetables and suffered three heart attacks. I remember my grandmother sitting out there at the round, white wrought iron garden table crying to my mother after my grandfather died. I remember watching my Uncle Pat, born Pasquale, bound out of the limousine in the cemetery after his funeral, suddenly unable to bear saying goodbye to his father, even if it was hard at that moment to picture my grandfather as a father, especially one like my own dad who seemed to so completely personify fatherhood: suit and tie and briefcase, a close shave and Old Spice, always a neatly folded handkerchief and Lifesavers in his suit jacket pocket. My dad stayed in the limo though, even if he started a bit when he saw Uncle Pat trot towards the grave, before his own son, also Pat, put his arm around him and led him back to the car, frightened for that brief moment by his brother’s grief, and I was frightened too, scared of the feelings I didn’t want to feel but even more scared of the fear these men were showing. Grown men. There was something not right about it. Even Dad couldn’t always keep it all in. Even his stalwart, sometimes impenetrable character had its vulnerabilities, found

44

Memoir

Matthew Aquilone

its limits somewhere. My dad stayed, his index finger flicking away a single tear, the slightest excrescence that did more to irrevocably alter my sense of the world than my grandfather’s death itself, or the sight of him in the coffin (my first dead body), or the embarrassing wailing of my grandmother and aunts. But if he could limit it all to one tear then I could do even better. I promised myself to not cry at that moment, or any other one if I could help it. In a photo taken many years later in our summer home in the Poconos, my dad and his brother stand next to each other in the kitchen, smiling, glasses of lemonade in their hands, a couple of paisans in nearly identical comb-overs and short sleeve button-ups living their almost identical American Dreams.

Now, in the KLM departure lounge at JFK the summer after my brother Michael’s first hospitalization, some four years before he will die of AIDS, on the eve of a European trip my parents have managed, I wonder if this is what my friend Evan meant when he said “God, you all look so Italian.” We went to college together. I had showed him a picture of my four brothers and me at our cousin JoAnne’s wedding in Massapequa a couple of summers before. All that accumulated brotherhood on display, like chapters in a

story or scenes in a film, everything connected and moving towards something, promising something. Suspense. A love story. Another happy ending flickering in the darkness.

“Destination, Italia,” my little brother Peter says into the camera. He is recording everything on our new eight-millimeter video camera, a late eighties, high-tech wonder roughly twice the size and weight of a brick. “Our ancestral homeland. Ciao, Francesco Rinaldi!”

“Actually,” my dad says, answering Peter, reaching once more into his jacket pocket for his itinerary, rendered in his impeccable Catholic School fountain pen cursive. “We won’t be going to Naples, where we came from. Although your grandfather really came from a town called Santangelo Dei Lombardi, near Avellino. Your grandmother’s “people” as they called them” –as though we aren’t familiar with the term – “came from Santangelo too but she was born here.”

“Their marriage was practically arranged,” my Aunt Bertha had once confided in us. “Maybe we go to Naples on the next trip,” my dad says.

“Ha! Are you a secret millionaire? This trip is not cheap,” my mom informs us,

45

“All that accumulated brotherhood on display, like chapters in a story or scenes in a film, everything connected and moving towards something, promising something.”

instinctively zipping up her pocketbook. “I hope you boys know that.”

My dad winks at us. My parents were raised during the Depression, then lived on city salaries and raised a big family. My mom reminds us constantly how they saved and sacrificed luxuries at home so that we would have money for special things like this trip. None of us really share her philosophy, however. We want life and we want it large and, most importantly we want it now, especially since the shit has officially hit the fan.

Things had started to get complicated back on Thanksgiving. Right before the big dinner started, my brother Vincent took me out for a walk and a talk around the quiet Brooklyn neighborhood where we grew up. As a little brother I’d always been thrilled to be taken into his confidences, even as they’d gotten more grown up. He lived in Manhattan with his friend Charlie, who I’d never met. Already, like Eddie, the oldest of us, and Michael, a year younger than Eddie, I knew Vincent was gay. Although it was in its way taken for granted, it was a fact as unformed and indeterminate as everything else in my life. I didn’t know what anything meant, or would.

He was ascendant that Thanksgiving Day, firing on all pistons, so handsome in his trendy haircut, trendy black jeans and hip chunky shoes and happier than I’d seen him in a while. He had moved out of our little house out of Midwood with its modest detached houses and

moved into himself. The East River that separates Brooklyn from Manhattan was a compelling boundary. Once Vincent had crossed over – he didn’t really want people to call him “Vinny” anymore – he knew he was home. A couple of blocks from our house however he stopped and put his arm around my shoulder and told me he’d tested positive for HIV.

“Honestly, it’s a relief to finally know. And I’m fine, and I’m going to be fine,” he said. “Anyway, don’t tell Mom and Dad.”

Honestly, despite the shock, my first thought was that I was surprised that it hadn’t been Michael to bring this news home first. As buff, butch and polished as he looked, as All-American, he had lived a practically nocturnal life the last few years, part of the drug-fueled, nonstop party of Fire Island circuit queens and Peter Pan club kids, something I’d only begun to understand – even if I understood all too well how connected it was to this new epidemic. Or maybe, once again, I didn’t understand anything.

Then in the spring, just as the campus erupted into life, bud and flower and bird and bee, restless college students baring bodies under the sun, Frisbee and hackysacks reappearing, along with my own optimism, giving myself a break from anxiety and all those worst-case scenarios, a knock came on my door during a particularly enthusiastic bong session in my room that changed everything. I was called to the funny, graffiti covered phone booth at the top of the stairs of the Co-

46

Op house where I lived. My mother was waiting on the line.

“Your brother,” she began. She didn’t have to finish. I knew exactly what she was going to say. Vincent wanted me to keep it a secret, and I had, but some secrets are too big for anyone to hide. Just like some possibilities are too great to ever believe they might not come to pass. I felt like a fool for thinking that we might dodge a bullet, that nothing bad might happen. While getting sick was pretty much an inevitability for someone with HIV I was shocked that it would have happened so quickly. I’d thought I, I mean Vincent, would have more time. But then my mother said, “Michael.”

Michael had been hospitalized suddenly with pneumocystis pneumonia, or PCP, one of the most common opportunistic infections for people with HIV and often the herald for the onset of AIDS itself. He’d been having trouble breathing, chest pain, fatigue, and the low-grade fever typical of PCP. One day he was alright and the next he was sick.

“Your father and I brought him to the hospital, needless to say it was a terrible shock,” she told me on the phone that day. Michael in his crisis had also come out to my parents. “The drugs I can accept but homosexuality is a grave sin.”

My mom had always been devout, but we’d always taken her orthodoxy with a grain of salt. As observant as she was, I’d always believed that the essence of her faith lay in the example of Christ’s infinite

love and not in dogma or doctrine, as educated in both as she was. To put it another way, she seemed to me more invested in the spirit of the word than the letter of the law. She was a pragmatist and a nice person, known as the problem solver in her office where she was a Special Education administrator in the public schools, where most of her friends and co-workers were Jewish. Sometimes our nickname for our mother was “The Saint.” She was a saint but the warrior type, Jeanne D’Arc in Aerosoles and clearance rack Liz Claiborne. But she sounded a little angry, which made me a little angry too, just something to add to the fear and nausea and dread.

“Did you know, Matthew?” she asked, her voice quavering at the other end of the line. It was probably the most serious question she had ever asked me.

“No,” I said, and I think I was telling the truth, but the situation was so complicated I wasn’t sure what specifically she was referring to. There were a million things I knew. There were a million things I suspected. Others I considered were likely. Plus I had a few surprises of my own. But no, I didn’t know that I had two brothers with HIV. I didn’t know that lightning had struck twice until right then.

“And what about you? Are you okay?” she asked next, for the first time, another question too big to be contained by that tiny phonebooth, too big perhaps to be contained by that moment. Once as a little boy, as my mother was turning off the

47

light on Peter and me at bedtime I called out “I’m afraid!”. I reached out from the top bunk and grabbed her sweater, that dependable cable knit Irish cardigan with the big wooden buttons. I don’t know why I was so suddenly terrified. The door was always left open. The light in the hall always on. “The only thing you have to be afraid of is me,” she told me firmly, taking me by the wrists and putting me back in bed. It was outrageous. I would have laughed in disbelief had I not known that what she said was true. She was too sensible to waste a moment on monsters or ghosts. It was bedtime and she had her correspondence to do and her Barbra Cartland novel to finish.

“I’m okay,” I said as convincingly as was possible in that tiny phone booth as my housemates shrieked and laughed in the hallway outside. Did she want me to tell her that I didn’t have HIV? Or did she want the topic to never come up between us?

“I’m okay,” I said again. I mean, what choice did I have?

I had always figured Michael had been infected by one of his first boyfriends, Stephen, a few years earlier. They had met at the Ice Palace on West Fifty-Seventh Street. Michael was barely legal. Steven at thirty-two was positively ancient. He was a short guy with a deep voice, Polish, average looks, compact build, longish hair, not in line with what I thought was Michael’s ideal at the time – his All-American Ken Dolls like the men