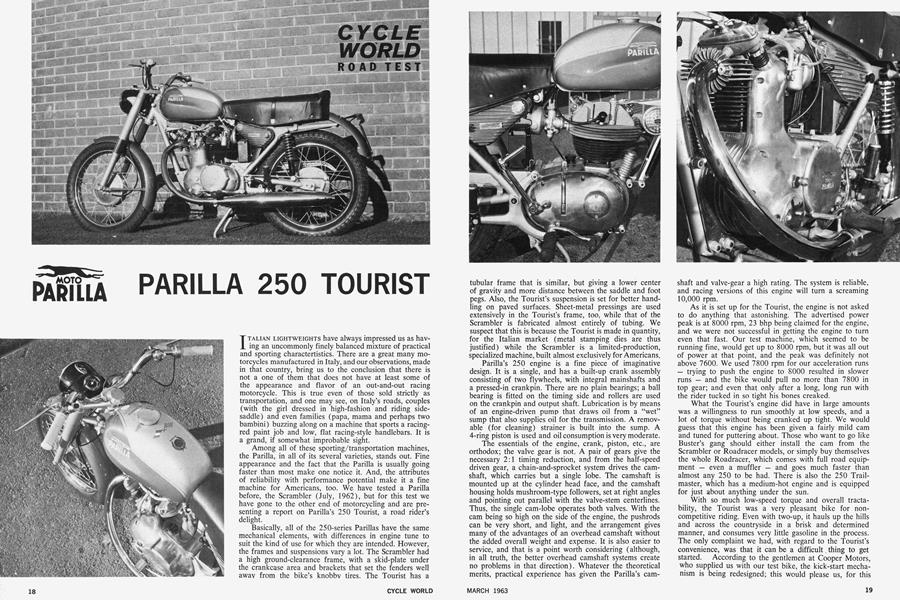

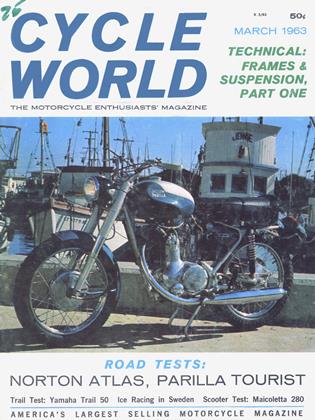

PARILLA 250 TOURIST

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

ITALIAN LIGHTWEIGHTS have always impressed us as having an uncommonly finely balanced mixture of practical and sporting charactertistics. There are a great many motorcycles manufactured in Italy, and our observations, made in that country, bring us to the conclusion that there is not a one of them that does not have at least some of the appearance and flavor of an out-and-out racing motorcycle. This is true even of those sold strictly as transportation, and one may see, on Italy’s roads, couples (with the girl dressed in high-fashion and riding sidesaddle) and even families (papa, mama and perhaps two bambini) buzzing along on a machine that sports a racingred paint job and low, flat racing-style handlebars. It is a grand, if somewhat improbable sight.

Among all of these sporting/transportation machines, the Parilia, in all of its several varieties, stands out. Fine appearance and the fact that the Parilia is usually going faster than most make one notice it. And, the attributes of reliability with performance potential make it a fine machine for Americans, too. We have tested a Parilia before, the Scrambler (July, 1962), but for this test we have gone to the other end of motorcycling and are presenting a report on Parilla’s 250 Tourist, a road rider’s delight.

Basically, all of the 250-series Parillas have the same mechanical elements, with differences in engine tune to suit the kind of use for which they are intended. However, the frames and suspensions vary a lot. The Scrambler had a high ground-clearance frame, with a skid-plate under the crankcase area and brackets that set the fenders well awav from the bike’s knobbv tires. The Tourist has a tubular frame that is similar, but giving a lower center of gravity and more distance between the saddle and foot pegs. Also, the Tourist’s suspension is set for better handling on paved surfaces. Sheet-metal pressings are used extensively in the Tourist’s frame, too, while that of the Scrambler is fabricated almost entirely of tubing. We suspect that this is because the Tourist is made in quantity, for the Italian market (metal stamping dies are thus justified) while the Scrambler is a limited-production, specialized machine, built almost exclusively for Americans.

Parilla’s 250 engine is a fine piece of imaginative design. It is a single, and has a built-up crank assembly consisting of two flywheels, with integral mainshafts and a pressed-in crankpin. There are no plain bearings; a ball bearing is fitted on the timing side and rollers are used on the crankpin and output shaft. Lubrication is by means of an engine-driven pump that draws oil from a “wet” sump that also supplies oil for the transmission. A removable (for cleaning) strainer is built into the sump. A 4-ring piston is used and oil consumption is very moderate.

The essentials of the engine, crank, piston, etc., are orthodox; the valve gear is not. A pair of gears give the necessary 2:1 timing reduction, and from the half-speed driven gear, a chain-and-sprocket system drives the camshaft, which carries but a single lobe. The camshaft is mounted up at the cylinder head face, and the camshaft housing holds mushroom-type followers, set at right angles and pointing out parallel with the valve-stem centerlines. Thus, the single cam-lobe operates both valves. With the cam being so high on the side of the engine, the pushrods can be very short, and light, and the arrangement gives many of the advantages of an overhead camshaft without the added overall weight and expense. lí is also easier to service, and that is a point worth considering (although, in all truth, the better overhead camshaft systems create no problems in that direction). Whatever the theoretical merits, practical experience has given the Parilla’s camshaft and valve-gear a high rating. The system is reliable, and racing versions of this engine will turn a screaming 10,000 rpm.

As it is set up for the Tourist, the engine is not asked to do anything that astonishing. The advertised power peak is at 8000 rpm, 23 bhp being claimed for the engine, and we were not successful in getting the engine to turn even that fast. Our test machine, which seemed to be running fine, would get up to 8000 rpm, but it was all out of power at that point, and the peak was definitely not above 7600. We used 7800 rpm for our acceleration runs — trying to push the engine to 8000 resulted in slower runs — and the bike would pull no more than 7800 in top gear; and even that only after a long, long run with the rider tucked in so tight his bones creaked.

What the Tourist’s engine did have in large amounts was a willingness to run smoothly at low speeds, and a lot of torque without being cranked up tight. We would guess that this engine has been given a fairly mild cam and tuned for puttering about. Those who want to go like Buster’s gang should either install the cam from the Scrambler or Roadracer models, or simply buy themselves the whole Roadracer, which comes with full road equipment — even a muffler — and goes much faster than almost any 250 to be had. There is also the 250 Trailmaster, which has a medium-hot engine and is equipped for just about anything under the sun.

With so much low-speed torque and overall tractability, the Tourist was a very pleasant bike for noncompetitive riding. Even with two-up, it hauls up the hills and across the countryside in a brisk and determined manner, and consumes very little gasoline in the process. The only complaint we had, with regard to the Tourist’s convenience, was that it can be a difficult, thing to get started. According to the gentlemen at Cooper Motors, who supplied us with our test bike, the kick-start mechanism is being redesigned; this would please us, for this one flaw does a lot to spoil the good impression created by the rest of the bike.

Insofar as riding comfort is concerned, the Tourist has few peers. Pegs, handlebars and saddle have good relative positions, and the suspension is quite comfortable. The transmission shifts as nicely as anything we have ever tried and the engine is smoother than some 250 twins. The Tourist is, in all respects, very well named.

Not directly connected to performance, but important to touring, too, was the tool-roll supplied with the bike. It contained a comprehensive selection and would be invaluable should something come to grief out on the road. To the same purpose, there was a tire pump, carried in brackets along the frame’s forward down-tube.

Even though the Tourist is no ball of fire at the drag strip, it is fun to ride. Braking and cornering power are both present in comforting amounts, and there is a lot of enjoyment to be had in lashing along a winding road. The suspension is both soft enough to be comfortable and firm enough to give good control, and we found ourselves looking for excuses to take this fine tourist bike out into the hills. Indeed, there was a fair amount of sneaking off just for a “ride around the block,” after which the Tourist and its rider would not be seen for some time.

Despite our criticisms, we all became very much attached to the Tourist, and did not like to see it go back. It was, if we may be excused for saying it again, fun to ride; no fire-breather, but an extremely pleasant and relaxing means of getting from here to there while sitting out in the breeze and enjoying the scenery. •

PARILLA

250 TOURIST

$579

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

March 1963 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

The Service Department

March 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings -

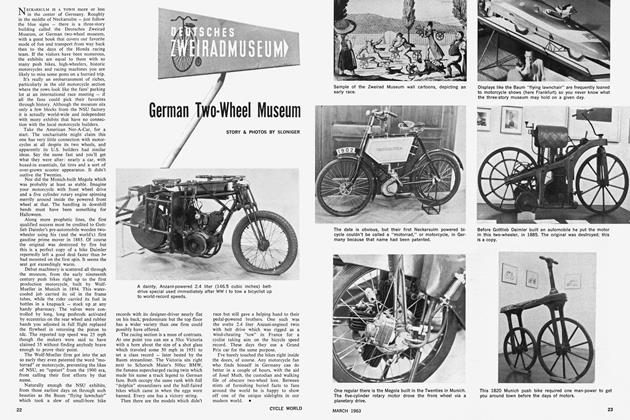

German Two-Wheel Museum

March 1963 By Sloniger -

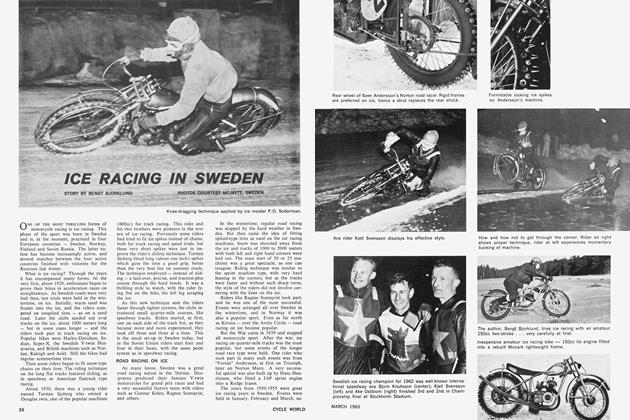

Ice Racing In Sweden

March 1963 By Bengt Bjorklund -

Trail Test

Trail TestYamaha Omaha Trail

March 1963 -

Technical

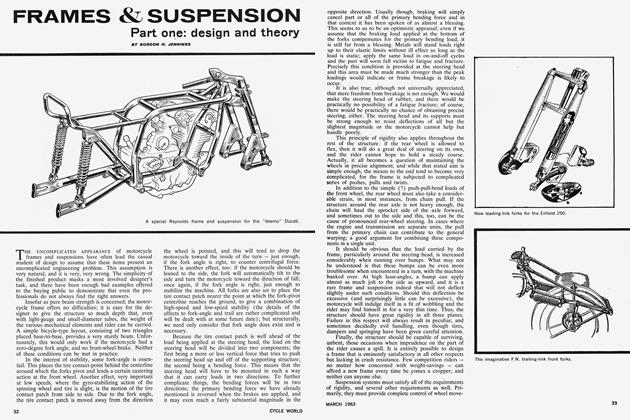

TechnicalFrames & Suspension

March 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings