Frank Welker & Jason Marsden goof off as Lennie & George on cartoon-ium for a couple hours and some folks just loathe this game? I'd hate to be y'all.

Usually I wouldn't hesitate to give this a flat 2-and-a-half stars rating. It's a blatantly unfinished, underbaked game based on a promising concept that's hard to do right. Think back to A Boy and His Blob, or another finicky partner-based puzzle platformer with loads of personality. When cute and/or funny characters chafe against a mediocre or simply bad game loop, that's enough of a put-off to get the whole genre condemned. (Ironic, given how the Floigan's property could actually be condemned, what with spiders on the lot and a blue-blooded realtor swooping in to snag the joint.) So it's unsurprising that Floigan Bros. has become the object of ridicule, both light and serious, in today's retro streaming landscape. So I'm gonna be a bit nice to this doomed duo, the Stolar-approved console mascots no one wanted.

Consider, though, how much this game just doesn't care whether you like, dislike, love, or hate it. Sometimes you just need Two Men. They're two himbos, they're loony, and they'll do what they want. Yes, their flaws are strong, but their irreverence is stronger. They've been critically neglected for over 22 years. Of course there have been bugs and jank, but they always come to terms with their differences because games like this comes once in a console's lifetime. By playing Floigan Bros. you will receive not just the Marx Brothers-ness of their antics, but the weirdness of the game's history as well.no apologies for the copypasta

Knowing anything, the game's original creator, ex-Bubsy voice actor Brian Silva, has too many horror stories about getting it into production. Floigan Bros. started life as an ill-fated attempt to recreate the glory days of Laurel & Hardy or the Three Stooges for a modern gamer audience. Accolade did some pre-production for it as a PlayStation game to release in 1996, but that company's decline led to the game's hiatus until SEGA & Visual Concepts picked up Silva's pitch. Mind you, the latter studio mainly created the Dreamcast's best known sports games, from NFL 2K to Ooga Booga (yeah, that's a stretch, but online minigames can get competitive!). Back in the 16-bit console era, though, VC had done a couple of their own puzzly, platformer-y games with mixed success. Them working on this previously abandoned Marx Brothers-esque pastiche wasn't so out of place after all. The original 1995 design document showed a lot of confidence already.

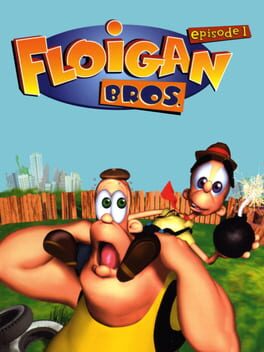

Just one look at that nutty cover art, and what you can actually do in this piece of interactive media, seems beyond belief. It's half puzzle platformer, half minigame collection, all with a coat of cheesy, unironic '40s Hollywood ham and humor. Hoigle & Moigle would fit right into a Termite Terrace parody of the popular comedy double-acts from that period. And the Of Mice and Men comparison is hardly unfounded. Moigle's soft spot for woodland critters isn't far removed from Lennie's fatal love for bunnies. There's something of a dark undercurrent at play here, from the Rocky & Bullwinkle-esque villainy threatening the brothers, to the uncanny spiders you teach Moigle to finally ground-pound despite his fears.

Kooky jokes and jukes define Hoigle & Moigle's daily life. The minigames and emotion system both play into the characters' expressiveness, and I almost always have a smile or sensible chuckle at what they're doing. Sure, most of this game's simple and easy to blaze through, almost simplistic with its riddles and sidekick manipulation. And the brownie points grind needed just to teach Moigle critical skills pads out the runtime more than I'd like. But it makes for a quaint pick-up-and-play experience which perfectly fits what the developers went for. I also get a kick out of chasing down magpies, screwing with Moigle's pathfinding during tag, and the musical transitions tied to his changing moods.

Realistically, this game's release was always a long shot. It took the efforts of Visual Concept's skeleton crew, led by Andy Ashcraft (War of the Monsters, PS2) and help from ex-Sonic designer Hirokazu Yasuhara, to get this out late in the Dreamcast's life. And while this technically pioneered or at least promised the episodic game format we know today, it only ever received a smattering of minor DLC add-ons which didn't see the light of day until last decade! This arguably might have done better if SEGA promoted it to an enhanced XBOX release, but having that last-minute platform exclusive clearly mattered more. This all explains the game's relative lack of content and playtime vs. what you would have payed back in the day. DC owners probably overlooked the price-to-value ratio just because any exclusive this interesting was worth the money then, though.

Obscure as it is, Floigan Bros. continues to entice and beguile all but the most hardy of classic game fans. Jerma, WayneRadioTV, and other streamers can't help but poke and prod at the game for a bemused audience. The few speedrunners I've seen playing this have their own commentary on it, often pointing out the somewhat buggy, janky programming you'll notice. For me, this remains one of the most interesting examples of SEGA's swan song ambitions. It hails from a time when the Dreamcast hosted all kinds of design experiments, from the successful (Shenmue, Jet Set Radio) to the forgotten (Headhunter, OutTrigger). Something told me there was more to this game than most would consider, given its "mid"-ness. I vaguely recall browsing the original SEGA website for it, confused by the classic American film humor and references but intrigued regardless.

What's one to do when an adventure in game development this unusual has so little coverage outside of memes? I had my own solution back in high school (Fall 2011, start of my junior year). After learning about designer Andy Ashcraft's role in fleshing out and finishing Floigan Bros., I e-mailed him some questions and thankfully got a considerate reply. Silva's been interviewed about the game recently, but I'd like to ask Yasuhara and other ex-devs some questions before compiling these primary comments into a fully-fledged retrospective. What I learned from Ashcraft alone tells me how much of a labor of love this game became.

Likely because Yasuhara came into the project very late, Ashcraft didn't have a lot to share about working with him, other than having a strong working relationship. Visual Concepts mainly started making the game back in '97, led by studio head Scott Patterson and a newly-recruited Ashcraft. The first problem they encountered was how to naturally integrate everything about Moigle into an accessible game loop. As I learned in the email chain, the big galoot had to be "somewhat unpredictable and be able to (or seem to) make decisions on his own about what to do and when to do it". On the other hand, VC considered how Moigle needed to "know what the player is wanting to do at all times, especially in tight life-or-death situations". They swiftly abandoned the do-or-die part, going for a less stressful set of puzzles and sequences which players could better manage.

In every part of the game's environments, the devs placed "distraction points" that Moigle responds to, a veritable sheep to your shepherd. It's easy for players to notice how the chatty, scheming cat-tagonist laps up Moigle's attention when nearby. Same goes for the aforementioned spiders, being one of the few entities strong enough to wreck his mood. Tweaking all these fragile variables, often with only one programmer available due to VC focusing on sports games (and talented staff leaving for greener pastures), greatly delayed production. It's a small miracle the game came out at all, even as Ashcraft and then Yasuhara had plenty of time to design it. Production woes aside, the former designer still considers this project an early triumph in building a game around a relatively natural, lively AI character dynamics...better than contemporaries like Daikatana, anyway.

Nothing like this existed on consoles at the time. Even the PlayStation port of the original Creatures wouldn't release until 2002, so almost a year after. Sure, you could argue that Chao raising in the Sonic Adventure games was close enough, but combining a learning AI with simple but elaborate world-puzzle progression was no mean feat. It's debatable how fun this actually is as a concept, but I'm far from deeming this as odd shovelware the way some do. Floigan Bros. has a lot of body and soul you can still experience, even without the historic context (though that helps!). Its mini-games are short enough to never get on my nerves—most are at least a little fun—and the junkyard possesses a palpable sekaikan, that lived-in verisimilitude which brings this beyond mere slapstick. This could have aged a bit better graphically, but the excellent animations and Jazz Age soundtrack feels like an early go at what games like Cuphead have accomplished recently. Tons to appreciate, overall.

Give the Floigan Bros. experience a shot, people! Maybe I'm a lot softer towards this than I should be, and I won't argue against anyone pointing out the jank or how it feels like a misbegotten Amiga-era oddity. But it still feels like too many rush to judge this one as harshly as I've seen. Few vaporware games emerge from their pupa into anything this polished, especially towards the end of a troubled console's lifecycle. Even fewer tackle a style of humor and homage this unattractive yet admirable, then or now. There's still a lot of room in the indie space for throwback Depression-era comedy games, something Floigan Bros. doesn't exactly nail either. The game's just too funny, replayable, and earnest for me to rag on, and we're still discovering neat parts of it today, from developer histories to previously-lost DLC. It's a relevant part of not just the Dreamcast's legacy, but the tales behind many decorated game developers. Plus it's got Fred from Scooby-Doo playing one of his all-time great Scrimblo roles, so what's not to love?

Fuck, maybe I'm just Floigan pilled after all.

Usually I wouldn't hesitate to give this a flat 2-and-a-half stars rating. It's a blatantly unfinished, underbaked game based on a promising concept that's hard to do right. Think back to A Boy and His Blob, or another finicky partner-based puzzle platformer with loads of personality. When cute and/or funny characters chafe against a mediocre or simply bad game loop, that's enough of a put-off to get the whole genre condemned. (Ironic, given how the Floigan's property could actually be condemned, what with spiders on the lot and a blue-blooded realtor swooping in to snag the joint.) So it's unsurprising that Floigan Bros. has become the object of ridicule, both light and serious, in today's retro streaming landscape. So I'm gonna be a bit nice to this doomed duo, the Stolar-approved console mascots no one wanted.

Consider, though, how much this game just doesn't care whether you like, dislike, love, or hate it. Sometimes you just need Two Men. They're two himbos, they're loony, and they'll do what they want. Yes, their flaws are strong, but their irreverence is stronger. They've been critically neglected for over 22 years. Of course there have been bugs and jank, but they always come to terms with their differences because games like this comes once in a console's lifetime. By playing Floigan Bros. you will receive not just the Marx Brothers-ness of their antics, but the weirdness of the game's history as well.

Knowing anything, the game's original creator, ex-Bubsy voice actor Brian Silva, has too many horror stories about getting it into production. Floigan Bros. started life as an ill-fated attempt to recreate the glory days of Laurel & Hardy or the Three Stooges for a modern gamer audience. Accolade did some pre-production for it as a PlayStation game to release in 1996, but that company's decline led to the game's hiatus until SEGA & Visual Concepts picked up Silva's pitch. Mind you, the latter studio mainly created the Dreamcast's best known sports games, from NFL 2K to Ooga Booga (yeah, that's a stretch, but online minigames can get competitive!). Back in the 16-bit console era, though, VC had done a couple of their own puzzly, platformer-y games with mixed success. Them working on this previously abandoned Marx Brothers-esque pastiche wasn't so out of place after all. The original 1995 design document showed a lot of confidence already.

Just one look at that nutty cover art, and what you can actually do in this piece of interactive media, seems beyond belief. It's half puzzle platformer, half minigame collection, all with a coat of cheesy, unironic '40s Hollywood ham and humor. Hoigle & Moigle would fit right into a Termite Terrace parody of the popular comedy double-acts from that period. And the Of Mice and Men comparison is hardly unfounded. Moigle's soft spot for woodland critters isn't far removed from Lennie's fatal love for bunnies. There's something of a dark undercurrent at play here, from the Rocky & Bullwinkle-esque villainy threatening the brothers, to the uncanny spiders you teach Moigle to finally ground-pound despite his fears.

Kooky jokes and jukes define Hoigle & Moigle's daily life. The minigames and emotion system both play into the characters' expressiveness, and I almost always have a smile or sensible chuckle at what they're doing. Sure, most of this game's simple and easy to blaze through, almost simplistic with its riddles and sidekick manipulation. And the brownie points grind needed just to teach Moigle critical skills pads out the runtime more than I'd like. But it makes for a quaint pick-up-and-play experience which perfectly fits what the developers went for. I also get a kick out of chasing down magpies, screwing with Moigle's pathfinding during tag, and the musical transitions tied to his changing moods.

Realistically, this game's release was always a long shot. It took the efforts of Visual Concept's skeleton crew, led by Andy Ashcraft (War of the Monsters, PS2) and help from ex-Sonic designer Hirokazu Yasuhara, to get this out late in the Dreamcast's life. And while this technically pioneered or at least promised the episodic game format we know today, it only ever received a smattering of minor DLC add-ons which didn't see the light of day until last decade! This arguably might have done better if SEGA promoted it to an enhanced XBOX release, but having that last-minute platform exclusive clearly mattered more. This all explains the game's relative lack of content and playtime vs. what you would have payed back in the day. DC owners probably overlooked the price-to-value ratio just because any exclusive this interesting was worth the money then, though.

Obscure as it is, Floigan Bros. continues to entice and beguile all but the most hardy of classic game fans. Jerma, WayneRadioTV, and other streamers can't help but poke and prod at the game for a bemused audience. The few speedrunners I've seen playing this have their own commentary on it, often pointing out the somewhat buggy, janky programming you'll notice. For me, this remains one of the most interesting examples of SEGA's swan song ambitions. It hails from a time when the Dreamcast hosted all kinds of design experiments, from the successful (Shenmue, Jet Set Radio) to the forgotten (Headhunter, OutTrigger). Something told me there was more to this game than most would consider, given its "mid"-ness. I vaguely recall browsing the original SEGA website for it, confused by the classic American film humor and references but intrigued regardless.

What's one to do when an adventure in game development this unusual has so little coverage outside of memes? I had my own solution back in high school (Fall 2011, start of my junior year). After learning about designer Andy Ashcraft's role in fleshing out and finishing Floigan Bros., I e-mailed him some questions and thankfully got a considerate reply. Silva's been interviewed about the game recently, but I'd like to ask Yasuhara and other ex-devs some questions before compiling these primary comments into a fully-fledged retrospective. What I learned from Ashcraft alone tells me how much of a labor of love this game became.

Likely because Yasuhara came into the project very late, Ashcraft didn't have a lot to share about working with him, other than having a strong working relationship. Visual Concepts mainly started making the game back in '97, led by studio head Scott Patterson and a newly-recruited Ashcraft. The first problem they encountered was how to naturally integrate everything about Moigle into an accessible game loop. As I learned in the email chain, the big galoot had to be "somewhat unpredictable and be able to (or seem to) make decisions on his own about what to do and when to do it". On the other hand, VC considered how Moigle needed to "know what the player is wanting to do at all times, especially in tight life-or-death situations". They swiftly abandoned the do-or-die part, going for a less stressful set of puzzles and sequences which players could better manage.

In every part of the game's environments, the devs placed "distraction points" that Moigle responds to, a veritable sheep to your shepherd. It's easy for players to notice how the chatty, scheming cat-tagonist laps up Moigle's attention when nearby. Same goes for the aforementioned spiders, being one of the few entities strong enough to wreck his mood. Tweaking all these fragile variables, often with only one programmer available due to VC focusing on sports games (and talented staff leaving for greener pastures), greatly delayed production. It's a small miracle the game came out at all, even as Ashcraft and then Yasuhara had plenty of time to design it. Production woes aside, the former designer still considers this project an early triumph in building a game around a relatively natural, lively AI character dynamics...better than contemporaries like Daikatana, anyway.

Nothing like this existed on consoles at the time. Even the PlayStation port of the original Creatures wouldn't release until 2002, so almost a year after. Sure, you could argue that Chao raising in the Sonic Adventure games was close enough, but combining a learning AI with simple but elaborate world-puzzle progression was no mean feat. It's debatable how fun this actually is as a concept, but I'm far from deeming this as odd shovelware the way some do. Floigan Bros. has a lot of body and soul you can still experience, even without the historic context (though that helps!). Its mini-games are short enough to never get on my nerves—most are at least a little fun—and the junkyard possesses a palpable sekaikan, that lived-in verisimilitude which brings this beyond mere slapstick. This could have aged a bit better graphically, but the excellent animations and Jazz Age soundtrack feels like an early go at what games like Cuphead have accomplished recently. Tons to appreciate, overall.

Give the Floigan Bros. experience a shot, people! Maybe I'm a lot softer towards this than I should be, and I won't argue against anyone pointing out the jank or how it feels like a misbegotten Amiga-era oddity. But it still feels like too many rush to judge this one as harshly as I've seen. Few vaporware games emerge from their pupa into anything this polished, especially towards the end of a troubled console's lifecycle. Even fewer tackle a style of humor and homage this unattractive yet admirable, then or now. There's still a lot of room in the indie space for throwback Depression-era comedy games, something Floigan Bros. doesn't exactly nail either. The game's just too funny, replayable, and earnest for me to rag on, and we're still discovering neat parts of it today, from developer histories to previously-lost DLC. It's a relevant part of not just the Dreamcast's legacy, but the tales behind many decorated game developers. Plus it's got Fred from Scooby-Doo playing one of his all-time great Scrimblo roles, so what's not to love?