Lucio Fontana: The Man Behind the Cut

Known as the ‘Zorro’ of the canvas, Lucio Fontana went on to change the course of art history forever. His method? A simple, but by no means trivial, slash of his painted canvases. This emblematic and powerful gesture cemented him as the founder of Spatialism, a movement still highly regarded today.

With his torn canvases, Lucio Fontana was able to create a collective idea linked to a simple but very powerful gesture, which represents the very concept of Spatialism. Although many people may look at his work and think “I could do that”, it is helpful to reflect on the words of Bruno Munari, who said “When someone says: ‘I can do this too’, it means that he can do it again, otherwise he would have done it before.”

Lucio Fontana was born on February 19, 1899, in Rosario de Santa Fé, Argentina. His father was originally from Varese, Italy, and owned a company that specialized in cemetery pieces and monumental sculpture. As a boy, Fontana went to Italy to study at the Carlo Cattaneo Technical Institute and the Artistic High School of the Brera Academy in Milan. His artistic pursuits were interrupted when he fought in World War I, however he returned to Argentina in 1925, where he made his professional debut with the sculpture Melodias, a female portrait reminiscent of Rodin.

Fontana returned to Italy In 1927 and settled in Milan. Working for his father proved fundamental in this period: few people know that he made some of the sculptures in the city’s Monumental Cemetery. Thanks to his cousin, the architect Bruno Fontana, Lucio Fontana began to attend the studio of Adolf Wildt and later enrolled in his sculpture courses in Brera. His first commission for the cemetery, the face of the Madonna for the Mapelli family tomb, arrived shortly after, followed by commissions for other monumental artworks.

Related: Salvador Dalí: Art Crazy

Thanks to his training in sculpture, Fontana quickly engaged in the world of ceramics, finding some of his greatest inspiration in this discipline. In 1935 Fontana moved to Albisola, where he discovered the potential of ceramics and began a 30-year collaboration with Tullio Mazzotti (or Tullio d'Albisola, as Marinetti nicknamed him). Together they created works of futuristic inspiration and enjoyed great success in both Italian and international exhibitions.

Related: John Baldessari: The Irony of Conceptual Art

In the 1940s, Fontana began experimenting with neon, ultraviolet lights and fluorescent paints. He sensed the potential of working on the concept of space through these mediums, and they quickly became part of his artistic language.

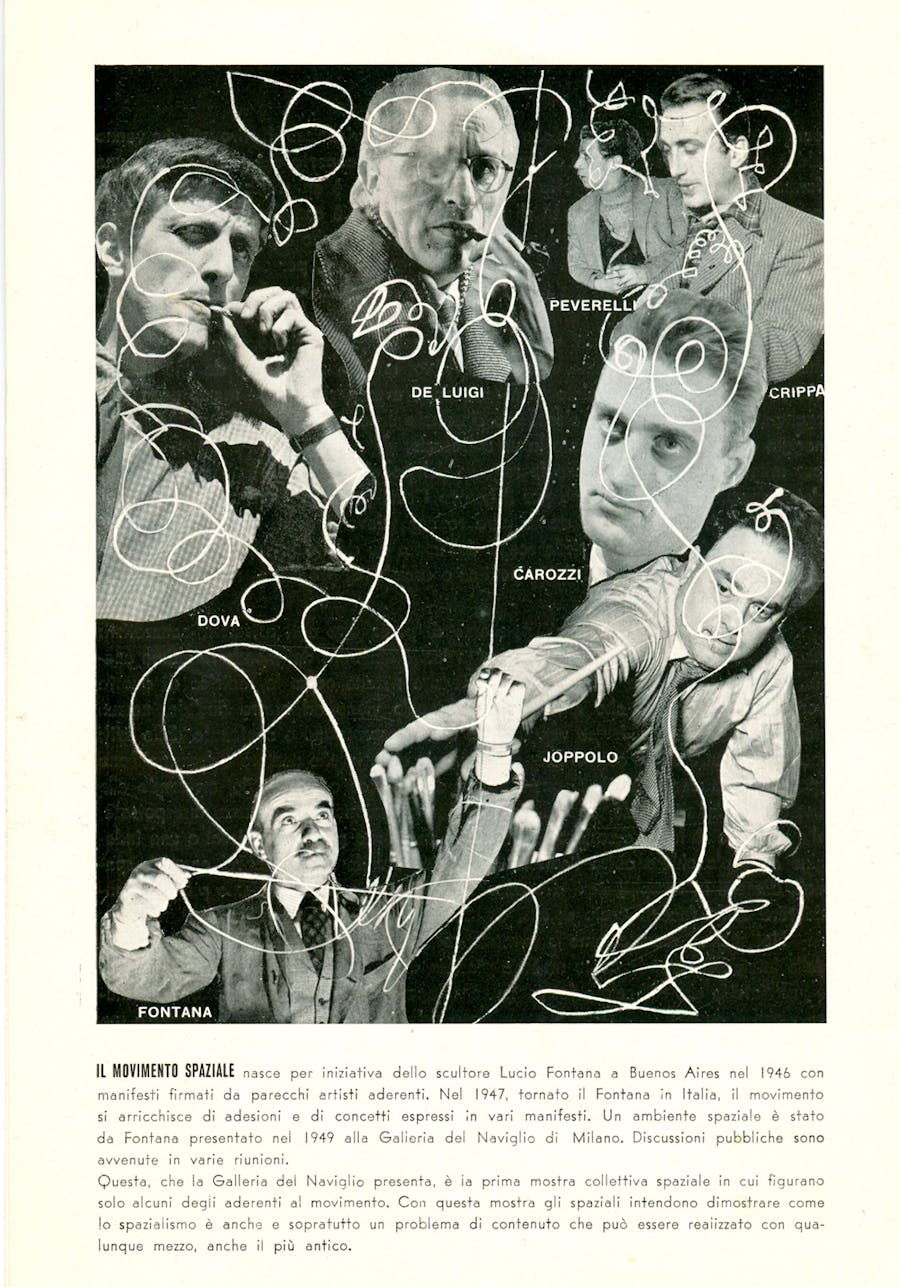

In the early years of World War II, Fontana was called back to Rosario di Santa Fe by his father to participate in the competition for the construction of the National Monument in La Bandera. Unfortunately they did not get the commission, and Fontana found himself relegated to Argentina due to the war in Europe. Although he found the Argentinian environment uninspiring, something new was born in him. In 1946 he wrote the Manifesto Blanco, which announced the need for a synthesis between space, time, color, sound and movement. He sought to redefine art, originating from the perspective of complex spatiality developed during the Baroque and of the concept of dynamism enhanced by Futurism. Fontana’s return to Italy in 1947 marked the beginning of a new and radical artistic perspective, and his first manifesto of Spatialism proclaimed a revolution in the visual arts.

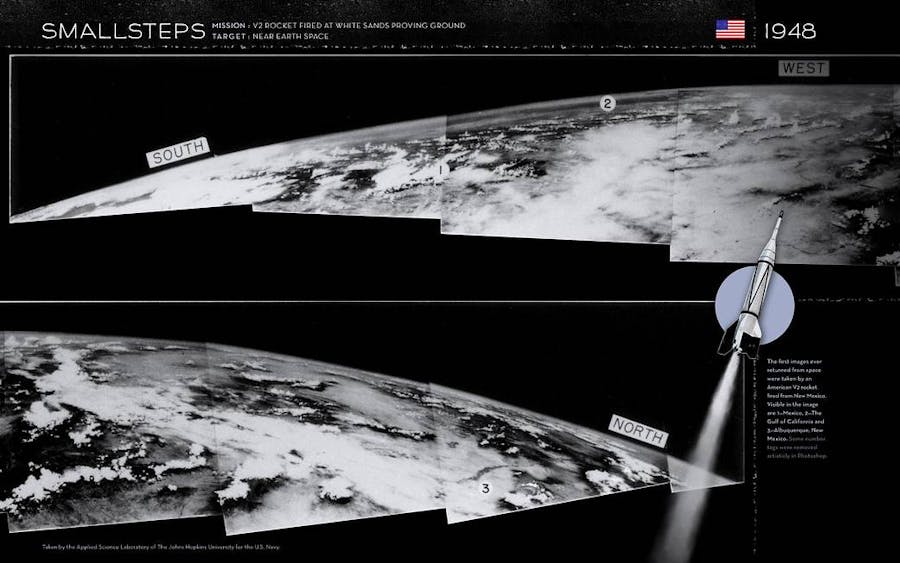

During the founding years of Spatialism, the world witnessed the first missile launches into space. In fact, on March 7, 1946, not long after the end of the Second World War but before Sputnik inaugurated the space age, the first experiments in space observation were carried out in New Mexico. The first images of earth, seen from an altitude of over 100 miles away in space, were published in well-known magazines such as Life and had a great impact on the imagination of Lucio Fontana and on the concept of Spatialism itself.

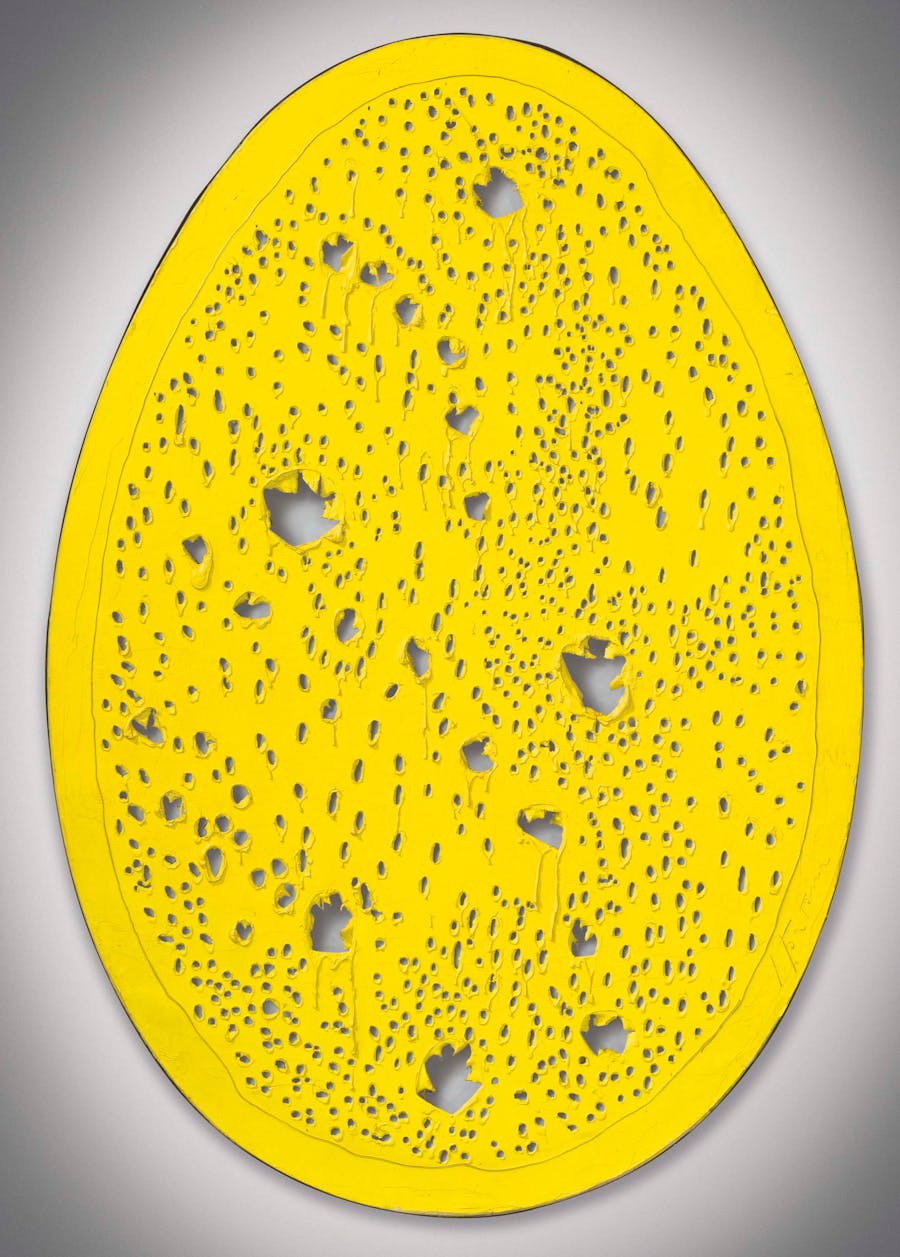

‘The end of God’ is a series made on oval frames, all the same size, which are distinguished by the presence of constellations of holes, gashes and graffiti on a monochrome base, sometimes covered with sequins. "For me they mean the infinite, the inconceivable thing, the end of figuration, the beginning of nothing," declared Fontana. In November 2015, at Christie’s auction dedicated to post-war and contemporary art in New York, the bright yellow ‘Space Concept’ of 1964, sold for $29,173,000,, setting a then new record for Lucio Fontana. This series is widely regarded as the aesthetic and conceptual peak of the Fontana's work, and the oval canvases are found in prestigious museum collections across the world, including those of the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid.