René Magritte: Bowler Hats with Belgitude

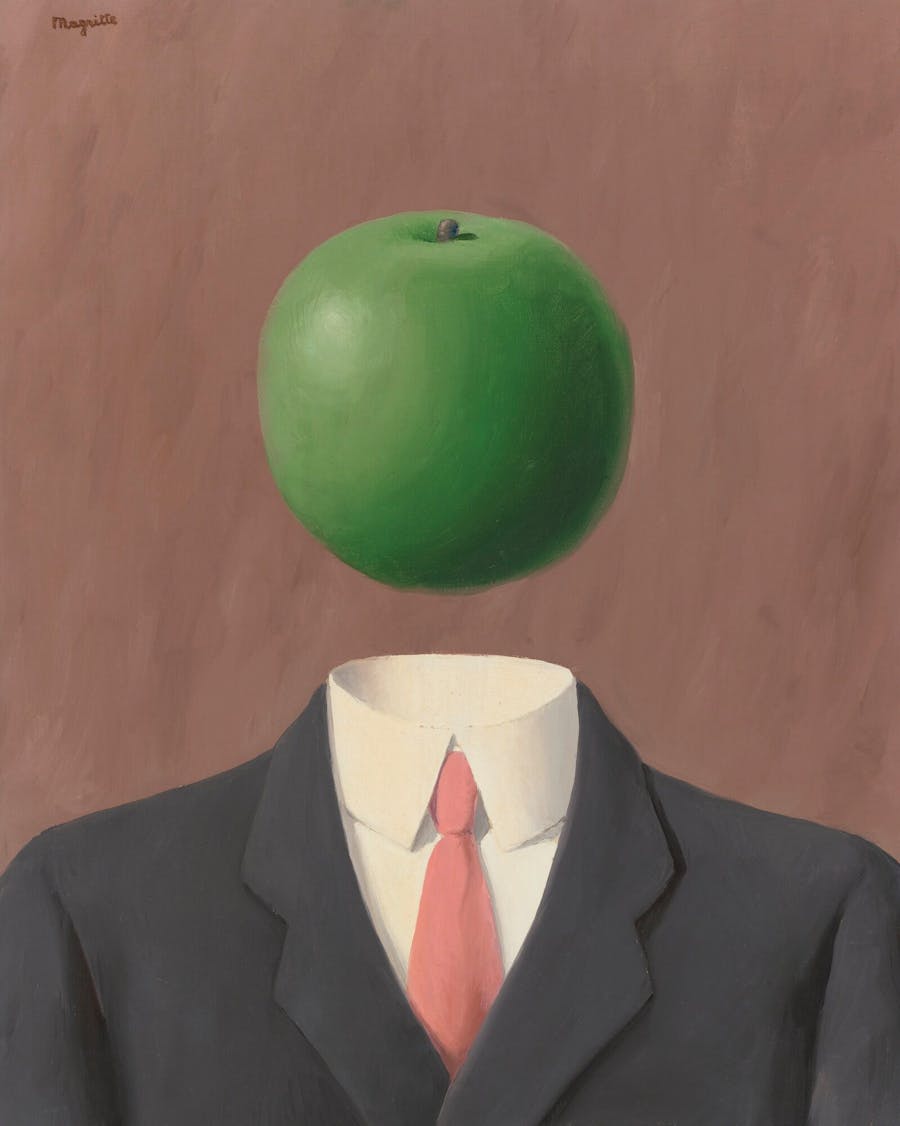

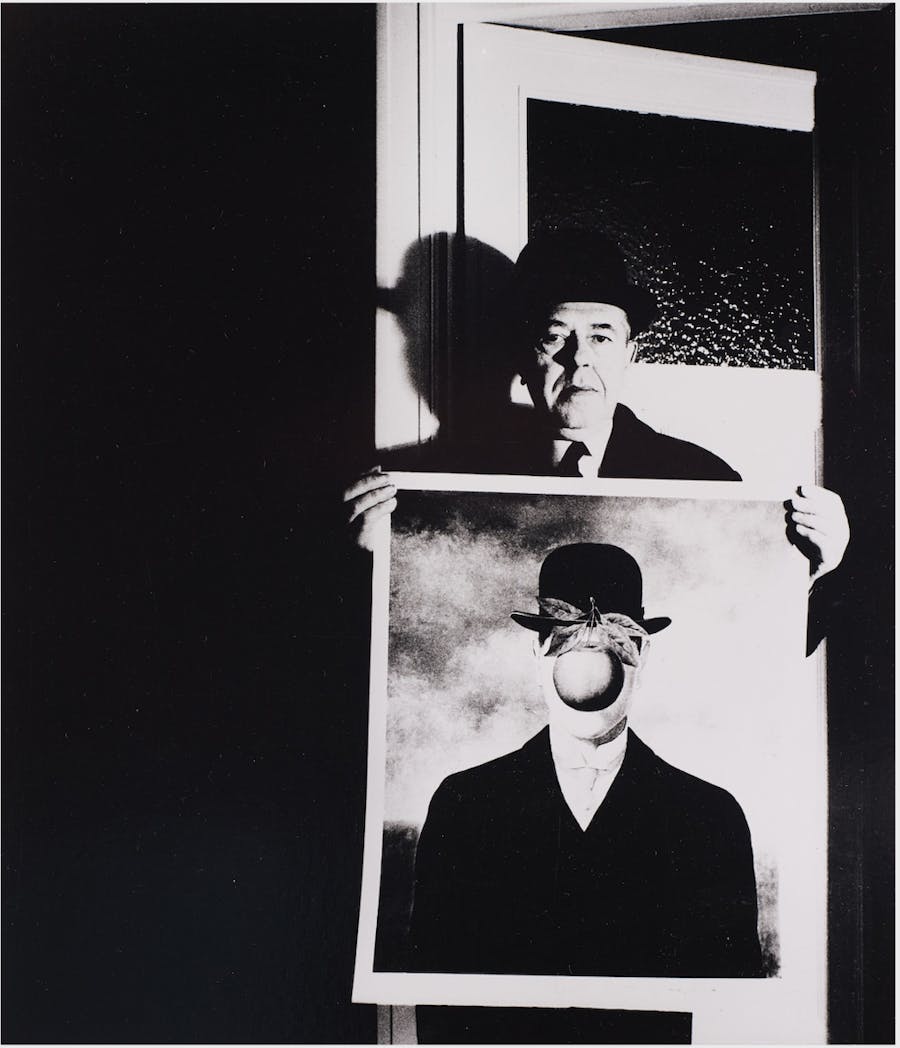

Pipes that aren’t pipes, apples lurking in a forest, cloudy blue skies, bowler hats that are anything but conventional… welcome to the world of Magritte, oozing with Belgitude.

Though born in 1898, it was in 1922 that René Magritte was truly born. This is the year when, aged 24, he discovered a reproduction of Giorgio De Chirico’s Song of Love, thanks to his friends Marcel Lecomte and E.L.T. Mesens, themselves already steeped in Surrealism. “My eyes saw thinking for the first time,” explained the young artist who, before this life-changing experience, tended to practice decorative painting and create billboard illustrations – more as a means of expression than out of necessity. Magritte’s father’s flourishing business activities ensured young Magritte the trappings of a bourgeois lifestyle, which he never really left behind. A world of bowler hats, no less.

Related: Surrealism and the Subconscious

Still, it’s difficult to say that Magritte had a cloudless childhood. He was 14 years old when, in 1912, his depressive mother, likely fed up with her husband’s philandering, threw herself into the River Sambre in Belgium’s Pays Noir (Black Country). This drama had an impact on Magritte’s work, even if he denied all psychoanalytic interpretations of it: commentators have been fond of seeing a connection between the many veiled faces he painted and the dressing gown that covered the face of his drowned mother when her body was discovered.

At the end of 1915, Magritte, raised by nannies and a literary diet of R.L. Stevenson, Edgar Allan Poe, Gaston Leroux and the comic series Les Pieds Nickelés, gave up his studies at the Athenaeum in Charleroi to settle on Rue du Midi in Brussels. This was not far from the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, where he sat in on classes until 1919 – though on a far from conscientious basis. He nonetheless attended classes taught by Symbolist painter Constant Montald and Art Nouveau poster designer Gisbert Combaz.

Anarchist writer Georges Eekhoud, who taught French at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts until his dismissal in the middle of World War I, also had a deep influence on Magritte. Among students, Magritte formed ties with Paul Delvaux and Pierre-Louis Flouquet, with whom he made his first steps into Cubism and Futurism. He also took part – alongside brothers Pierre and Victor Bourgeois, a filmmaker and an architect respectively – in the publication of the magazine Au Volant, and other avant-garde publications, most of which didn’t survive for long but still helped to contribute to the development of these artistic movements in Belgium.

Related: Why Was 'The Lost Jockey' Motif So Important to Magritte?

On a sentimental level, at the start of the 1920s, Magritte by chance came across his childhood sweetheart Georgette Berger at the Jardin des Plantes in Brussels. They married on June 28, 1922, and he had no other muses. With Georgette and Giorgio De Chirico, all elements were in place for the painter to really take off. His debut flight was his Jockey perdu (1926), a nod to – and a hyphen between – Dada, metaphysics and Surrealism.

In the mid-1920s, while producing numerous illustrations for films, the theatre, the automobile industry and major Belgian brands, Magritte helped to set up a Surrealist group in Brussels along with other leading figures, such as Paul Nougé, André Souris, Louis Scutenaire and Irène Hamoir.

In 1927, he moved to Perreux-sur-Marne in France, where he notably met André Breton, Paul Eluard, Max Ernst and Salvador Dali, and took part in artistic and intellectual activities with them until 1930. The Depression called him back to Belgium, for even if he no longer had any business dealings in his natal country, his renown there had already soared.

Related: Salvador Dalí: Art Crazy

In 1933, he held an exhibition at the Palais des Beaux-arts in Brussels, and three years later, his first solo exhibition in New York, at the Julien Levy Gallery. The next year, in 1937, he visited London, giving lectures and showing works at the London Gallery, owned by his friend and compatriot Mesens. He also fell out, then made up with Breton, contributing to and heading up new Surrealist publications, and also producing hundreds of works. Brimming with poetry, decoys, trompe-l’œil and wit, these works, beneath their harmless childlike and bourgeois appearances, veered towards subversion and anarchy. Through the corrosive humor of his painting bordered on absurdity, Magritte worked at destroying the foundations of all conventions of the so-called modern world.

See also: Andy Warhol: The Pope of Pop

The German invasion prompted Magritte to leave Belgium in May 1940. He lived in Carcassonne, France, for a few months, joined by some of his Belgian Surrealist friends, whose communist tendencies were already flagrant.

Back on home territory, René Magritte radically changed his style in the mid-1940s, drawing inspiration from Impressionist techniques while continuing his research into illusions. This so-called ‘Renoir’ period – even if the painter himself refuted the term – was followed by what was known as the ‘cow’ phase that gave rise to forty or so lurid paintings and gouaches attesting to purely Surrealist influences.

Related: Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Joie de Vivre on the Canvas

In the 1950s and ‘60s, several Magritte retrospectives were organized throughout the world, namely in the United States (MoMA, Chicago, Berkeley, Pasadena) where the artist enjoyed huge popularity.

Magritte died on August 15, 1967 and was buried beside his wife at Schaerbeek Cemetery, near Brussels. At the Magritte Museum, part of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts, the Belgian capital shows off a large proportion of works by this Surrealist painter who exemplified Belgitude that is so hard to define, but that well and truly exists.

Today, his work also sees immense popularity on the auction market. The current record price for a work by Magritte was achieved at Sotheby's in London by L'Empire des lumières, from 1961, which fetched £59.4 million ($79.7 million) in March 2022.

Find more articles in Barnebys Magazine

This is an updated version of an article originally published on August 15, 2018.