Religious or Radical: How the Guardia de Honor Shaped the Birth of a Nation

In the Jerrold Tarog film Goyo: Ang Batang Heneral, there is a sub-plot about General Gregorio del Pilar trying to stop the “brigands” who were attempting to disrupt activities in Pangasinan. These brigands were members of the Guardia de Honor, but perhaps only those who know their history recognize the group.

Who were the Guardia de Honor? Far from being a footnote in history, the Guardias and what they represented paint an interesting picture of the birth of the nation.

Religion and Revolution

The waning years of the 19th century were probably some of the most interesting periods in Philippine history. The 1890s and early 1900s were pivotal to the birth and future of the nascent Republic and were the stage for a series of contradictions among all facets of society.

One interesting and often overlooked portion of the Revolution was the great disconnect between the Katipunan’s struggle and the wider provincial unrest all over the Philippines. In this time of chaos and control, elite ilustrados and noted principalia vied for positions in the Revolution to fill power vacuums and secure their own wealth.

The country’s response was widely different. Politically aware citizens easily picked up the revolutionary situation and either took up the cause of the Katipunan or stubbornly clung to the old order. Most of the countryside, however, heeded the call of local charismatic leaders who promised something else: paradise.

The Religious Guardias

It’s hard to really state how important religion was to the Filipino during the Colonial Era. Life was centered on religion. Communities were built around churches and the colony was split into areas where religious orders operated. The church was the center of any town and the priest was one of the most important people, oftentimes more than the mayor, in the community.

Feast days punctuated important events of the year. Basic education was found within the walls of the church. The story of the Bible was told over and over again to the common man. Various religious forces in colonial Philippines made sure to weave and incorporate religion and God into the colony’s very fabric.

The use of religion was meant to silence the native Filipino and teach him that suffering in silence was Christ-like and what God intended. Instead, it taught people something else: that there is hope in struggle, that the evil empire cannot triumph over the oppressed poor, and that, in the same way the suffering Jesus received salvation, so, too, will the suffering Filipino receive salvation of cataclysmic proportion.

Which brings us to the Guardia de Honor. What was once a religious organization suddenly found itself radicalized by the Revolution, and incensed by its religious beliefs. A mix of religion and anarchism motivated the Guardias to take up arms and take land that they believed was rightfully theirs, going as far as to fight both the Katipunan and any foreign encroachment at the same time.

Bandits or Something More

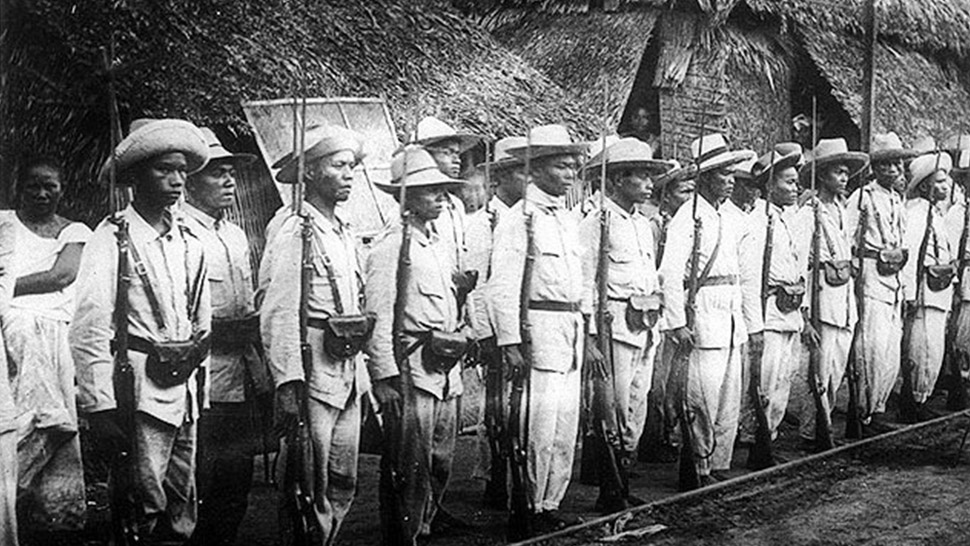

So who were the Guardia de Honor? Both the Katipunan leadership and the American occupying forces saw them as nothing more than brigands or pests that needed to be dealt with. They were certainly annoying: The Guardias held unquestioned command of Pangasinan and their numbers were easily in the thousands. They had people in towns all over the province, occupying the entire town of Cabaruan, turning it into a stronghold. They were even large enough to found the town of Natividad in 1901, which stands until today.

The Guardias were strong enough at the time that Aguinaldo seriously considered them a factor during his retreat north. He feared that camping in territory controlled by the Guardias posed problems.

At the same time, the U.S. forces were reluctant to enter territory controlled by the Guardias, thinking that it was overrun by bandits and highwaymen, and thus were another layer of criminality that needed to be dealt with.

That so many thousands of people were galvanized under a common cause was something that was more or less overlooked by both Aguinaldo and the occupying U.S. forces, who instead relied on the convenience of calling the movement mere brigandage. The Guardias were, in reality, spurred on by a mix of folk Catholicism and a desire for land.

Land and Taxes

Almost all members of the Guardias were peasants and farmers who tilled land owned by hacienderos and other principalia. During the Philippine Revolution, and especially during the Philippine-American War, these hacienderos and principalia disappeared or were driven out of their land by the war, leaving them empty.

The chaos and the promise that the Revolution would create true change in society created the idea, among thousands of farmers, that the time had come for them to rise. No longer should they be maltreated and stripped of dignity. No longer should they till land that wasn't theirs and pay unfair taxes. Farmers from all over rose up and stormed towns, often raiding town halls to destroy tax certificates, and began taking over land left behind by its owners.

The Guardias were no exception: Thousands of members readily rose up in order to free themselves from exploitation under an oppressive rule. They didn’t see the Revolution in terms of freedom from the Spanish, but instead wanted something more fundamental in being able to till their own land and gaining freedom from taxes; two points that they failed to see as achievable under Aguinaldo. Faced with no option, they decided to take their freedom into their own hands.

Ultimately, the story of the Guardias was short and bitter. The Americans were quick to crush them after they took Pangasinan. Their leaders were executed and the members scattered like the wind, never to be seen again. Today, the Guardias are merely subjects of academic study, or small plot points in historical drama.

But we mustn’t forget the significance of the Guardia de Honor. Their fundamental struggle, unfair distribution of land between landowners and farmers, is one that exists until now. Today, 75 percent of all Filipinos are farmers or peasants, while nine out of every 10 farmers do not own their own land.

The Guardias were certainly one of the first to rise up for land, and for that they were called fanatics and brigands before being executed by a state that refused to address their concerns. This is a story that still holds true. The characters may have changed, and the names may be different now, but the desire for land stays the same.

Sources:

Sturtevant, D. Guardia de Honor: Revitalization Within the Revolution. Asian Studies

Ileto, R. (1979) Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840-1910.

Guerrero, M. (2015) Luzon at War: Contradictions in Philippine Society; 1898-1902. Anvil Publishing.

Joaquin, N. (2005) A Question of Heroes. Anvil Publishing.

Alvarez Guerra, J. (1887) Viajes por Filipinas: De Manila a Tayabas.