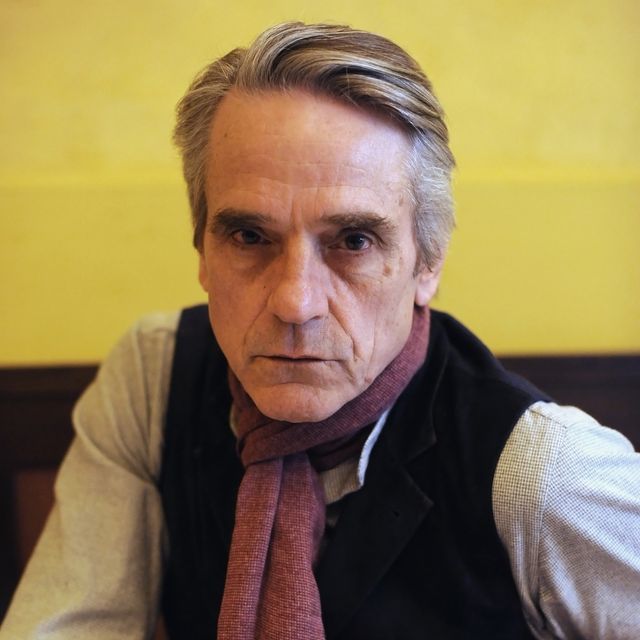

You might not be able to tell when you watch Jeremy Irons as Watchmen’s Adrian Veidt—dressed in a vest and button-down, awash with lamp and moonlight, fussily reaching over his boat, reeling up, inspecting, and tossing about half-dead babies—but he’s having a helluva time.

For the last four weeks, Irons has regaled us with the kind of frozen-corpse-stomping behavior native only to the best of sardonic television, which HBO’s Watchmen most certainly is—fishing scene included. And Irons wasn’t too mortified when he read the part and learned of his character's wicked foibles. “Not at all,” he says in the Gramercy Park Hotel, chatting just a day before he took the stage at New York Comic Con. In fact, pausing, thinking: “Maybe a hint of excitement.”

Baby-fishing wouldn’t be the most villainous—or villain-seeming—act a Jeremy Irons character has ever committed; he's played numerous literary, cinematic, and historical villain from Judas, to Scar, to Lolita’s Humbert Humbert to Renaissance mafioso pope Rodrigo Borgia. In fact, the English actor may be at his absolute best when he’s playing the unredeemable, bad, monstrous.

And perhaps no monster is as monstrous—or as fun—as Adrian Veidt, the isolated, midnight fisherman whose claim to comic villainy centers around a false flag operation 30 years earlier to unite the U.S. and Soviets. The operation entailed dropping a synthetic squid on Manhattan and killing some 3 million people, a crime for which Veidt seems to have escaped scot-free. Only much later does he, for unknown reasons, reemerge in this confused countryside exile, where we find him at the start of the series. He's alone, save for two servants, Mr. Philips and Ms. Crookshanks, cloned AI creatures that Veidt grows and must, while they're in baby form, yes, fish out of a lake. Veidt isn’t so much killing children, as much as he's harvesting them.

“I thought of those films of industrial chicken farming, where all the chicks come down the chute and the sorters are there picking up the cocks and chucking them away,” Irons says with a grin, explaining his preparation for the scene.

Despite his four-decades-plus acting career, Irons’ post-'80s television roles are surprisingly sparse. Before Showtime’s The Borgias, he hadn’t starred in a TV show for 25 years. He said the enthusiasm of Watchmen series creator Damon Lindelof brought him back to the small screen a second time. “When he talked to me about the character, I thought: [this] would be fun, enigmatic, and bizarre,” Irons says. “I was just interested to see whether I can make that work.”

He also wanted to see whether audiences would “go for it,” this isolated character who, as of the mid-season mark, has seemingly little to do with the series’ overall plot—and, outside of his moonlight angling, has seemingly little to do beside build catapults, curb stomp the corpse of his robot/clone(?) butler, Mr. Philips, and massacre a dozen sets of Mr. Phillipses (and Ms. Crookshankses, the other butler) with forks and dinner knives after a “long night.” But what can Irons say? He enjoys “comedy.”

Irons said Lindelof had a small suggestion for sustaining viewer attention throughout these scenes. “Damon encouragement me to push the envelope a bit,” he says. Push the envelope? Just a bit.

If the challenge was bringing a horrendous man to some humorous form of humanity, Lindelof and company may have found no better actor to cast.

Irons, who grew up in a small town on the Isle of Wight in the U.K, fell into acting almost instinctively. Faced with the horror of professional adult life and struck with a vagabond's desire, Irons answered an ad in the local newspaper for a stage job; it was either theater or the circus or the carnival, Irons reasoned—anything but an office. After attending theater school, Irons appeared in a bevy of stage performances in London before making his television and then film entrance. Since then, he’s amassed plenty of accolades: a Tony in 1982 for his stage role in The Real Thing; an Oscar for Best Actor in 1990 for Reversal of Fortune; and multiple Emmys, including one in 2006 for the Earl of Leicester in Elizabeth. Tony, Oscar, and Emmy all giving Irons something of an acting triple crown.

Irons may be at his unsung best, though, when playing horrible, horrible men—and one very horrible lion. He says these roles—Humbert, Borgia, Scar—despite their shared tyranny and brooding violence, are all entirely unique. “They’re all intriguing, but in different ways,” he says. Nevertheless, they maintain essential characteristics: “enigmatic, human, powerful, but failing. I hope they contain many of the frailties that we all contain,” says Irons. “The imperfection of humanity.”

These features of humanity and frailty and enigma find a kind of hyperbolic expression in Veidt, whose crimes are horrible beyond measure (3 million people, at the close of the graphic novel). And yet ... he is a joy to watch; he's eccentric, lonely, yet oddly mirthful.

Irons, now 71, shares a similar sprightliness, and there’s a bit of art imitating life in his Veidt—villainous acts excluded—as he parades the grounds of his castle on horseback and tinkers in his workshop. Irons himself lives part-time in a 15th century castle on the west coast of Ireland, which he restored over six years—the castle itself untouched for hundreds of years before the actor impulsively purchased the land. After all, he enjoys the countryside, he says. Sailing. Riding. Fixing things. Being away from it all. He's not trying to escape.

Which reveals something of Veidt’s isolation: something sad hidden behind the initial image of humor.

Of The Comedian, a morally-bankrupt vigilante who appears in the graphic novel, the character Rorschach explains: “He saw the true face of the 20th century and chose to become a reflection, a parody of it.” Irons’ Veidt seems to occupy a similar space of 21st century parody: alone, surrounded by inept, though sophisticated technology. Lonely, as Irons explains, “filling time.” All while the series’ more pressing issues play out miles (and possibly dimensions) away. (The real focus of the series, according to writer and showrunner Damon Lindelof: “race and policing in America”—making Veidt something of an Old Order Evil.) He doesn’t care.

Irons notes various parallels between Veidt’s station and the way all of us, out here, move about our lives—“the way we use uniform and masks to cover up behavior or to allow our behavior to seem acceptable,” he explains. Sorting through lake babies like factory chickens reveals something of this everyday play-acting: routine and banality (and technology) hiding and masking loneliness. “He's covering up,” says the actor. Like all of us: “covering up to be braver.”

Masks and faces and uniforms are standard materials for an actor, and Irons has spent decades covering up, though in a more literal, actorly way; nothing else brings him so much joy. Veidt may be one of the few characters, the few masks, who himself actually wears a mask, making the role extra-intriguing. It’s a differentiating feature between Veidt and some of Irons’ other bizarre men; as he himself puts it, it would be “slightly tedious” if all these famously foul roles required the same kind of mask.

And fortunately, Irons says, few confuse his own self with those many hard, tyrannous men he’s become oh-so-good at portraying—the ones that, maybe more than the award-winning parts, might just define his career. “[People] mostly know I'm an actor,” he says, simply. “They don't expect me to be a pope, or a missionary, or a pedophile.” He pauses. “Or a lion.”

Perhaps on his next trip to the grocery store, Irons’ produce-sorting might draw some stares. But for now, even with a voice that may still scare children, he’s comfortable being himself in his castle.