Meta-painting. A Journey to the Idea of Art

11/15/2016 - 2/19/2017

With Meta-painting, the Museo del Prado is offering a new approach to its collection in the latest in a series of exhibitions that began in 2010 with Rubens and continued with Captive Beauty (2013) and Goya in Madrid (2014). This series has aimed to offer visitors the chance to reflect on the Museum’s own collections and to look at its works in a new context which encourages different interpretations.

Meta-painting proposes a journey that begins with mythological and religious narratives on the origins of artistic activity at the dawn of the modern age and concludes in 1819, the year of the Prado’s foundation. The exhibition thus also celebrates the 197th anniversary of the Museum’s founding as a temple of the arts, signifying their full acceptance as disciplines of social utility.

Two aspects central to the Prado – the Spanish royal collections and Spanish art – provide the context for the exhibition’s structure. Furthermore, these are two inseparable terms, given that the evolution of Spanish art was determined by the existence of the royal collections. The survey offered by the exhibition is a wide-ranging and varied one, including paintings, drawings, prints, books, medals, examples of the decorative arts and sculptures. Twenty-two of these works have been loaned by eighteen museums and collections, including the Fundación Casa de Alba, the National Gallery in London, the Museo de Bellas Artes in Seville, the Banco de España and the Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Arts de San Fernando in Madrid.

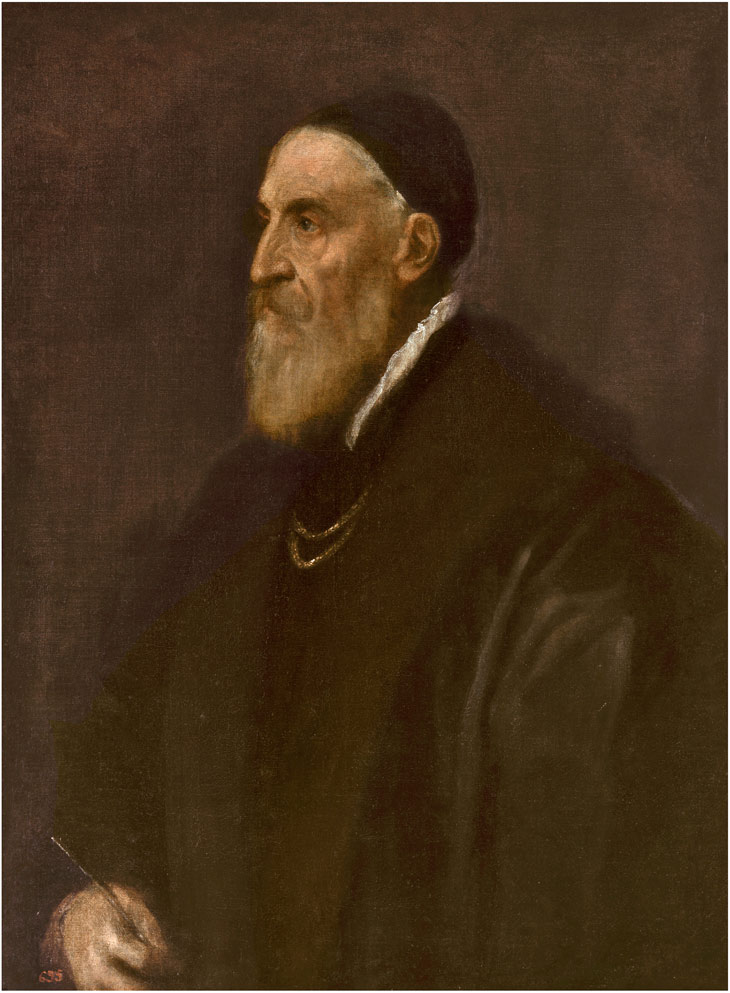

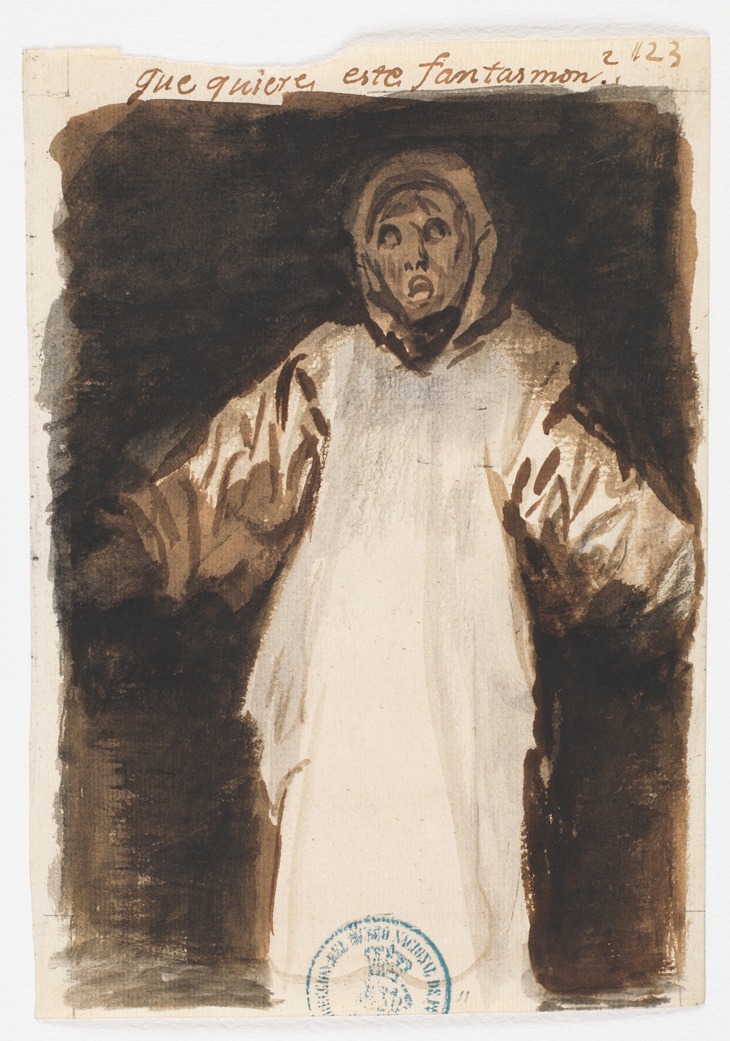

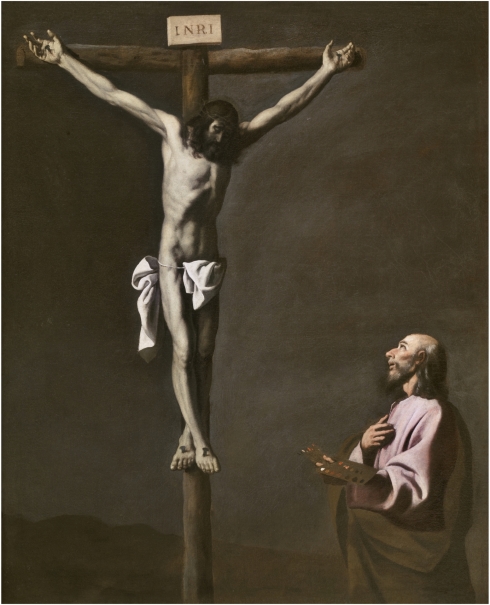

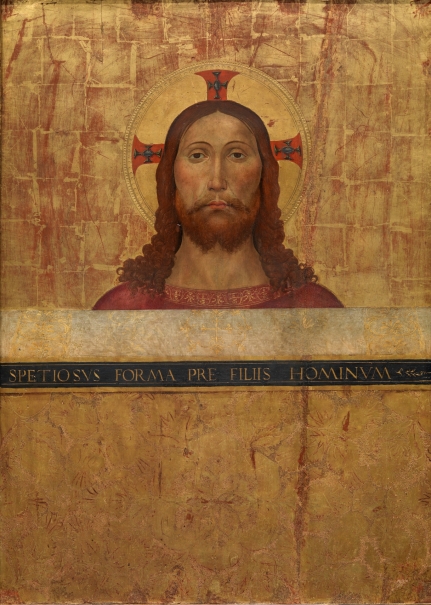

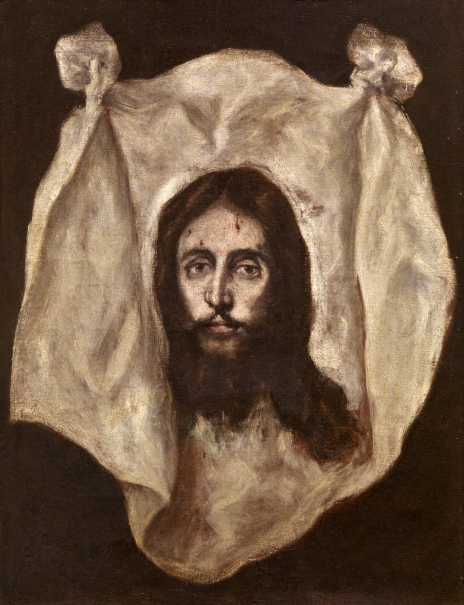

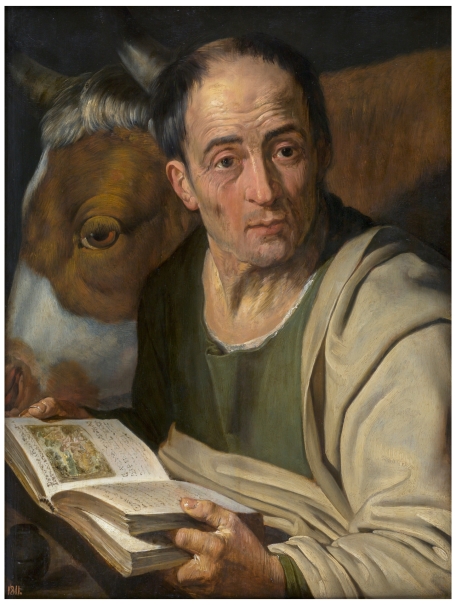

All the 137 works in the exhibition refer to art or to images, either as self-portraits of creators such as Titian, Murillo, Bernini and Goya; or because they include other paintings and sculptures, such as Saint Benedict destroying Idols by Ricci and Arachne by Rubens; or because they analyse issues relating to the definition of art and its history, such as José García Hidalgo’s book Principles for studying the very noble and royal art of painting […] and Goya’s Portrait of Jovellanos.

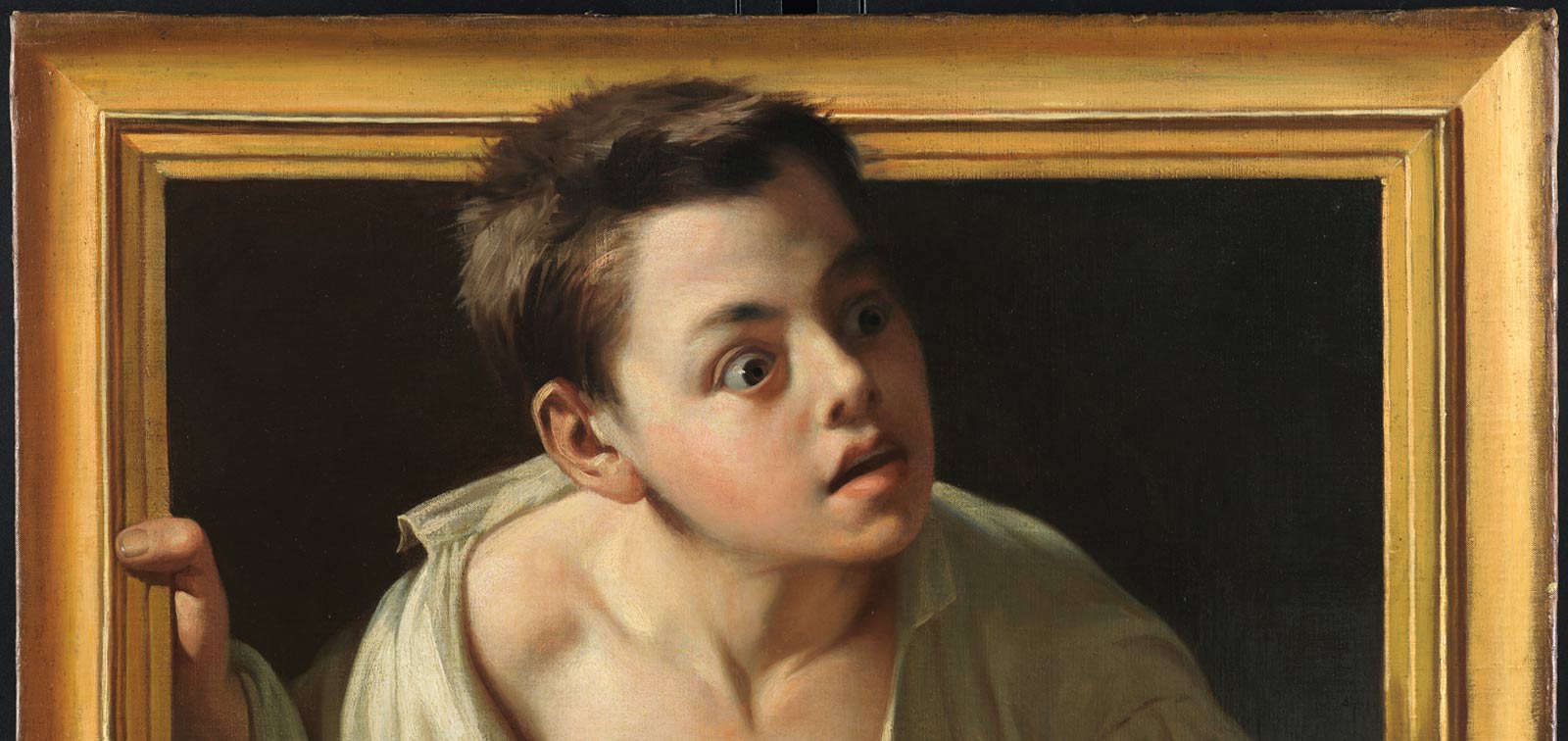

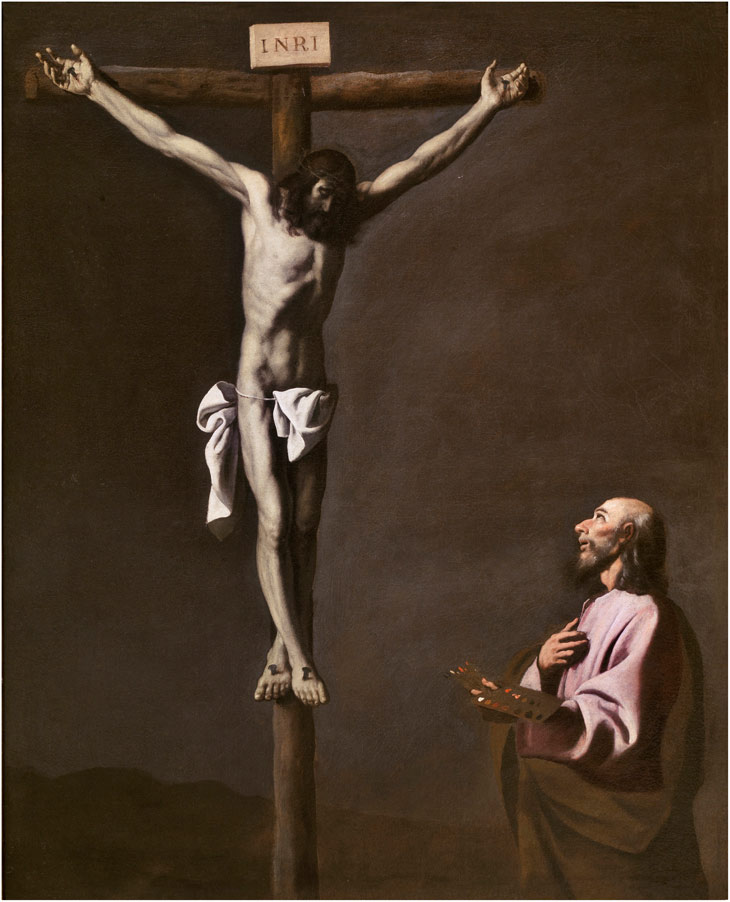

The exhibition’s “journey” is divided into different phases. Fifteen sections focus on the relationship between art, the artist and society, each one of which looks at a specific issue, among them: the powers attributed to religious images; the role played by the “painting within the painting”; artists’ attempts to break through the pictorial space and continue it towards the viewer; the origins and practice of the idea of artistic tradition; portraits and self-portraits of artists; places for the creation and collecting of art; the origin of the modern concept of art history; the subjectivity that emerged in self-portraits from the Enlightenment onwards; and the importance of the concepts of love, death and fame in the modern artistic discourse.

The exhibition also represents a tribute by the Museo del Prado to Cervantes on the 400th anniversary of his death as it includes a section on Don Quixote as one of the great examples of self-referential literature, juxtaposed with Las Meninas. Thus, just as Cervantes’ text is a “novel within a novel” so Velázquez’s painting is a “painting on painting” in which the artist not only depicts himself painting but which involves various important issues regarding the potential of the art of painting and the role of the painter.

Las Meninas will remain in Room 12 of the Villanueva Building where it is habitually displayed but it is present in the exhibition through a modern facsimile of part of Laurent’s graphoscope which is displayed alongside editions of the two parts of Don Quixote, reminding visitors that these two masterpieces of the Spanish Golden Age are both reference points in the history of meta-fiction.

- Curator:

- Javier Portús, Chief Curator of Spanish painting (up to 1700) at the Museo Nacional del Prado.