Astrophysicists have spotted a faraway object that's hotter than any contemporary theory can explain, a discovery that might require scientists rewriting galaxy operation manuals for years to come. The first fruits of these mind-boggling observations were just published by an international group of scientists led by the Russian astrophysicist Yuri Kovalev in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.

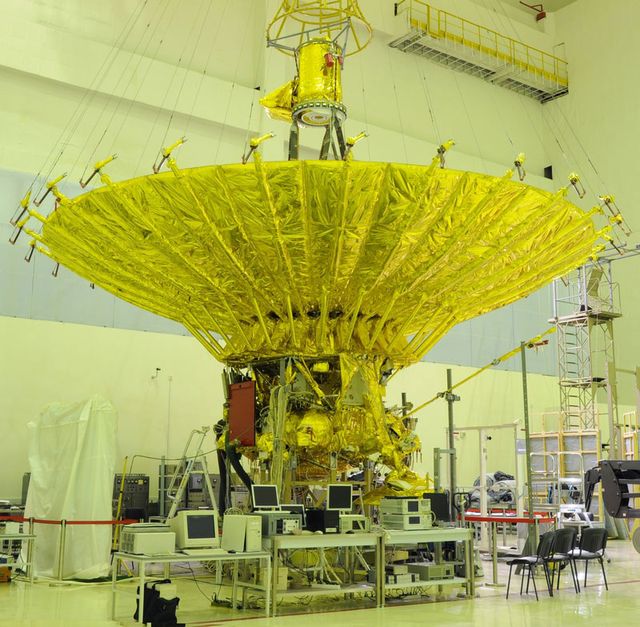

"I believe that behind this remarkable result lies a new chapter in the exploration of the faraway universe," said Nikolai Kardashev, the head of the Spektr-R (Radioastron) orbital observatory project, which was instrumental in the latest breakthrough.

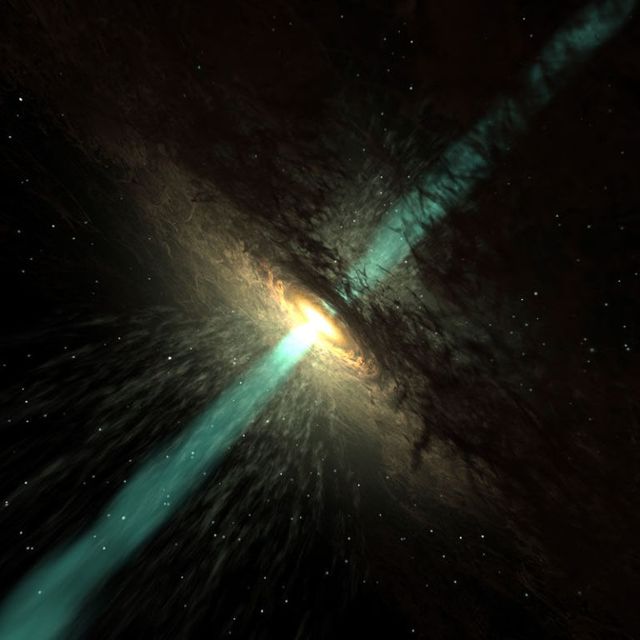

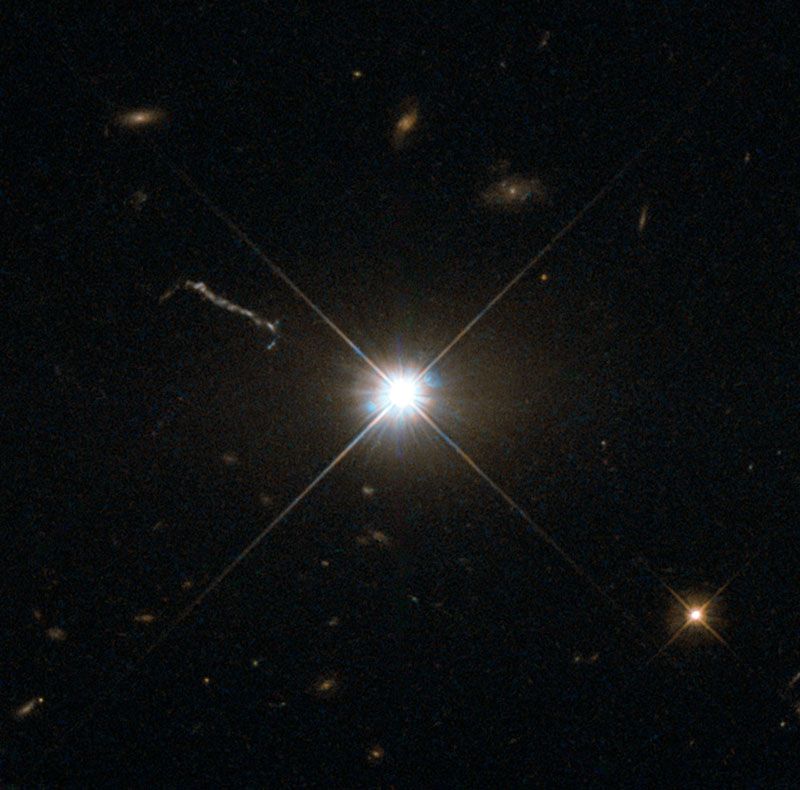

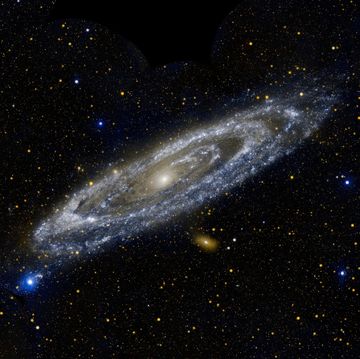

Working in tandem with ground-based radio telescopes around the world, the Russian Spektr-R satellite, orbiting more than 200,000 miles from Earth, can listen to radio signals from across the universe with unprecedented clarity. In the latest effort, Earth-based radio telescopes in the continental United States, Germany, and Puerto Rico joined with Spektr-R to achieve a resolution thousands of times higher than it is possible with the Hubble Space Telescope. The sprawling combined telescope then focused on the famous Quasar 3C273 in the constellation Virgo. Half a century ago, this same object became the first to be identified as a super-bright core of a faraway galaxy. The bizarre object was so luminous that it almost completely overwhelmed the combined glow all the stars in its host galaxy located billions of light years away from our own Milky Way. It turned out that like many of its siblings, Quasar 3C273 hides a giant black hole at its center that sucks in material around it and spews out narrow jets of plasma back into space.

Not surprisingly, astrophysicists are fascinated by the super-extreme conditions at the heart of quasars, and after years of research, scientists postulated that jets of plasma emitted by quasars could not reach more than 500 billion degrees kelvin. According to the current theory, the heating beyond that threshold would cause a massive transfer of energy from electrons to photons and result in quick cooling. However, the latest measurements made possible by Spektr-R show that some mysterious mechanism brings the effective temperature at the core of the quasar to a seemingly impossible range from 20 to 40 trillion degrees—at least 10 times above the theoretical ceiling. And this particular quasar may not even be the most intense.

"I can hint you that there are objects from which we expect much higher brightness than the one we see in 3C273," Spektr-R project scientist Yuri Kovalev tells Popular Mechanics. The ongoing research project has already taken the temperature of nearly 200 objects in the universe, he says, and a multinational group of scientists is now busy processing the results.

"In a sense, we are saying that even such an 'ordinary' quasar as 3C273 displays brightness and temperatures far above the expected levels," Kovalev says, "This means that our traditional theories about how quasars' cores emit light are incorrect. Obviously, for a scientist, there is nothing more pleasant, exciting and successful than to get a result that does not comply with a theory, because this is the most effective way to push the scientific research further."

So far, scientists have drafted at least four possible hypothesis to explain the oddball observations. According to one idea, the jet-producing machine inside quasars could be accelerating protons rather than electrons. But because protons as so much more massive, it would require an unfathomably powerful central engine to do this. "To put it simply, all four explanations have problems," Kovalev says.

In the meantime, the Spektr-R space observatory presses on mission. Launched on a Ukrainian-built Zenit rocket on July 18, 2011, the satellite is about to exceed its five-year manufacturer warranty.Although harsh conditions of space, particularly radiation, are taking their toll on the spacecraft, the flight control team so far has managed to continue a productive scientific mission by switching to backup systems. According to Kovalev, technical issues have not yet degraded the scientific results.

Inspired by the success of Spektr-R, Russian scientists proposed a much more complex space radio telescope known as Spektr-M or Millimetron. The new instrument will be able to register millimeter and sub-millimeter bands of electromagnetic spectrum not only in conjunction with ground-based antennas but also on its own, peering farther into the Universe than any ground-based telescope can. Because of its high cost and many technical hurdles, though, Spektr-M is not expected to blast off into orbit before 2025.

Anatoly Zak is the publisher of RussianSpaceWeb.com and the author of Russia in Space: the Past Explained, the Future Explored.